Supporting the University Research Enterprise via Open Access Publishing: Case Study from a Carnegie Research 2 University

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Evolving Role of Libraries in the Academic Research Enterprise

2.2. Academic Library Positions Supporting Research

2.3. Linking Library Support to Research Outcomes

2.4. Open Access as Enterprise Research Support

2.5. Transition to Case Study

3. Case Study

3.1. Institutional Context

3.2. Library Support for the Research Enterprise

3.2.1. Office of Research Relationships

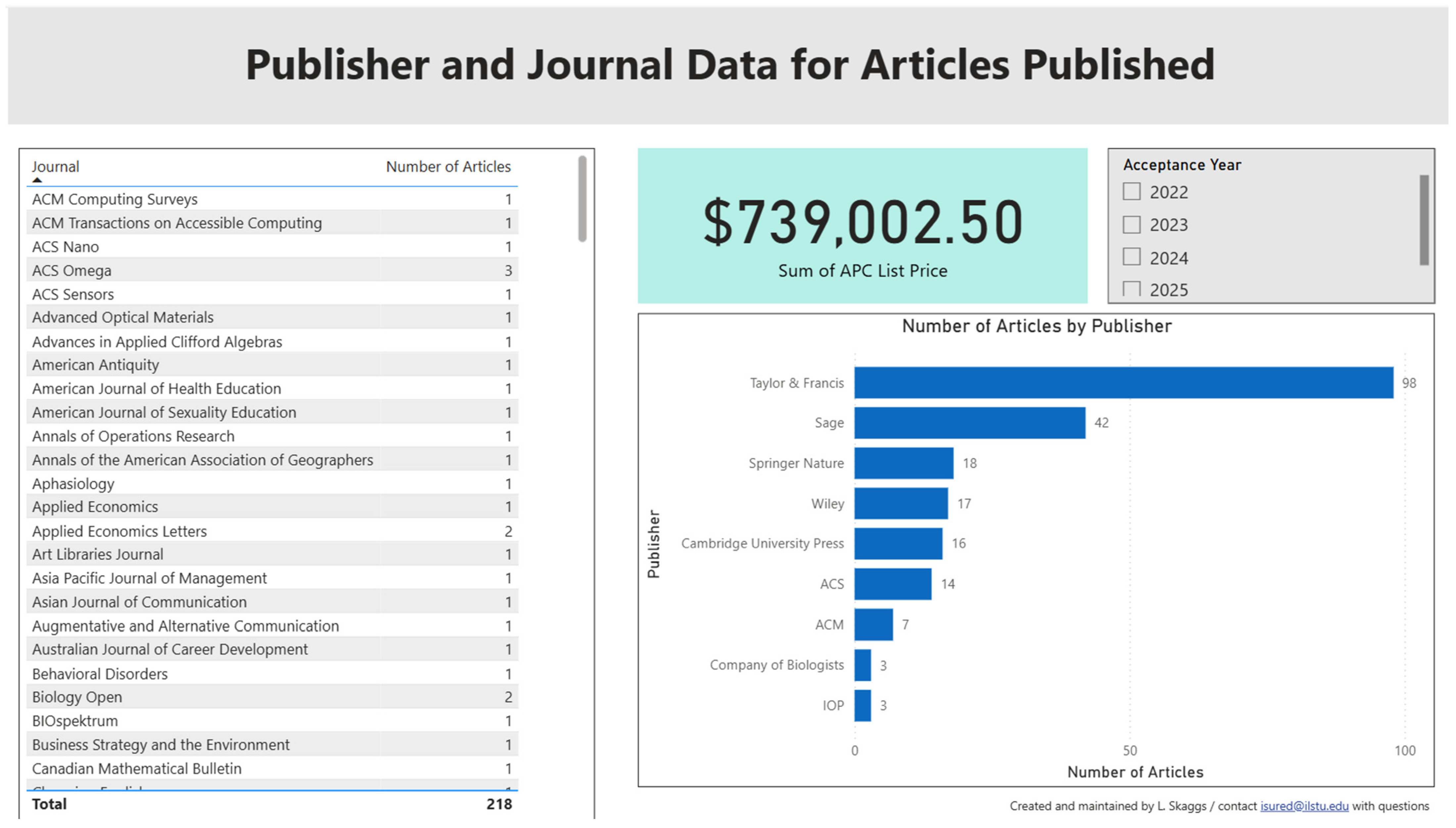

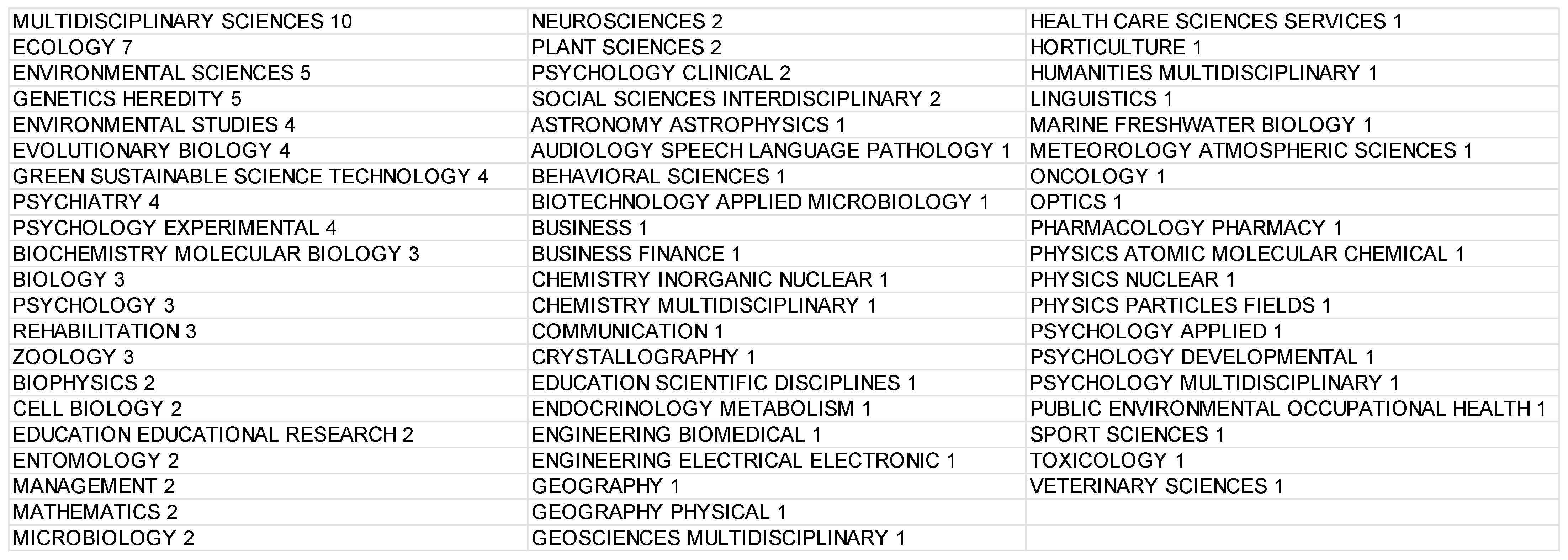

3.2.2. Publisher Relationships

3.2.3. Infrastructure and Workflows

Acquisitions

Author Experience

Collection Assessment

Discovery and Access

Institutional Repository

3.3. Summary of Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APC | Article processing charge |

| AVPR | Associate Vice President for Research |

| OA | Open access |

| TA | Transformative agreement |

References

- Armstrong, M. (2014). Institutional repository management models that support faculty research dissemination. OCLC Systems & Services, 30(1), 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspesi, C., & Brand, A. (2020). In pursuit of open science, open access is not enough. Science, 368(6491), 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association of Research Libraries. (2010). New roles for new times: An ARL report series in development [written by Janice M. Jaguszewski and Karen Williams]. Available online: http://www.arl.org/component/content/article/6/2893 (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Auckland, M. (2012). Re-skilling for research: An investigation into the role and skills of subject and liaison librarians required to effectively support the evolving information needs of researchers. Available online: http://www.rluk.ac.uk/files/RLUK%20Re-skilling.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Björk, B. C. (2017). Open access to scientific articles: A review of benefits and challenges. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 12, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourg, C., Coleman, R., & Erway, R. (2009). Support for the research process, an academic library manifesto. OCLC Research. Available online: https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/12828 (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Bradley, C. (2018). Research support priorities of and relationships among librarians and research administrators: A content analysis of the professional literature. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 13(4), 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosz, J. (2020, January 28). Critical roles for libraries in today’s research enterprise. 2019 Critical Roles for Libraries in Today’s Research Enterprise Symposium, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R., Dortmund, A., & Lavoie, B. (2020). Social interoperability in research support: Cross-campus partnerships and the university research enterprise [OCLC research report]. OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. Available online: https://www.oclc.org/research/areas/research-collections/institutional-stakeholders-in-research-support.html (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. (2026). Available online: https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/institution/illinois-state-university/ (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Corrall, S., Kennan, M. A., & Afzal, W. (2013). Bibliometrics and research data management services: Emerging trends in library support for research. Library Trends, 61(3), 636–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council on Library and Information Resources. (2008). No brief candle: Reconceiving research libraries for the 21st century. Available online: https://www.clir.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2016/09/pub142.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Craiglow, H., Vitale, C. H., & McGeary, T. (2025, December 8). Guest post—Funding research services: How libraries are exploring cost recovery models. Scholarly Kitchen. Available online: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2025/12/08/guest-post-funding-research-services-how-libraries-are-exploring-cost-recovery-models/ (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Efficiency and Standards for Article Charges (ESAC). (2026). Registry initiative registry tracks open access agreements across publishers and institutions. Although it is not comprehensive, it is a useful tool for seeing the significant increase in open access agreements. ESAC, Registry. Available online: https://esac-initiative.org/about/transformative-agreements/agreement-registry/ (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- European Commission. (2019). Research and innovation, European research infrastructures. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/strategy/strategy-research-and-innovation/our-digital-future/european-research-infrastructures_en#:~:text=Research%20Infrastructures%20are%20facilities%20that,sited%2C%20distributed%2C%20or%20virtual (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Franklin, B. (2001, August 12–16). Academic research library support of sponsored research in the United States. 4th Northumbria International Conference on Performance Measurement in Libraries and Information Services (pp. 105–111), Pittsburgh, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, B. (2007). The privatization of public university research libraries. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 7(4), 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, K. L. (2008). Research library publishing services: New options for university publishing (pp. 1–40). Association of Research Libraries. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED500889 (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Healy, A. M. (2010). Increasing the visibility of the library within the academic research enterprise. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, R., Burns, D., & Thoms, B. (2019). Altruism or self-interest? Exploring the motivations of open access authors. College & Research Libraries, 80(4), 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickerson, H. T., Brosz, J., & Crema, L. (2022). Creating new roles for libraries in academic research: Research conducted at the University of Calgary, 2015–2020. College & Research Libraries, 83(1), 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illinois State University. (2025). Excellence by design: 2024–2030 Illinois State University’s strategic plan. Available online: https://strategicplan.illinoisstate.edu/ (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Illinois State University. (2026). Office of research 2025 annual report. Available online: https://research.illinoisstate.edu/downloads/FY25%20ORGS%20Annual%20Report.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Kaufman, P. T. (2008). The library as strategic investment. Liber Quarterly, 18(3/4), 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowledge Rights 21. (2025, November 17). The case for viewing libraries as research infrastructures. Available online: https://www.knowledgerights21.org/news-story/libraries-as-research-infrastructures/ (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Krzak, A., & Tate, D. (2016). Large scale implementation of open access: A case study at the University of Edinburgh’s College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine. Journal of EAHIL, 12(2), 8–12. Available online: https://era.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/16058/EAHIL%20Krzak%20Tate.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Laakso, M., & Ayeni, P. (2025). Why engage with transformative agreements in scholarly publishing? Analysis of customer and publisher press release statements. Journal of Documentation, 81(7), 420–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. W. (2017). The 2.5% commitment [position paper]. IU Indianapolis Scholarworks, University Library Faculty and Staff Works. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippincott, S. K. (2016). The Library Publishing Coalition: Organizing libraries to enhance scholarly publishing. Insights: The UKSG Journal, 29(2), 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C. E. (2025). Boosting the identifier ecosystem of the University of Colorado Boulder faculty. Library Resources & Technical Services, 69(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKiernan, E. C., Bourne, P. E., Brown, C. T., Buck, S., Kenall, A., Lin, J., McDougall, D., Nosek, B. A., Ram, K., Soderberg, C. K., & Spies, J. R. (2016). How open science helps researchers succeed. eLife, 5, e16800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Medicine, Global Affairs, Board on Research Data and Committee on Toward an Open Science Enterprise. (2018). Open science by design: Realizing a vision for 21st century research. National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piwowar, H., Priem, J., Larivière, V., Alperin, J. P., Matthias, L., Norlander, B., Farley, A., West, J., & Haustein, S. (2018). The state of OA: A large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles. PeerJ, 6, E4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlins, B. (2024). Are transformative agreements worth it? An analysis of open access publication data at the University of Kentucky. Library Resources & Technical Services, 68(1–2), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, B., & Scott, M. (2025). Open access and citation impact: Modality, funding, publisher, and disciplinary trends at the University of Kentucky. Library Resources & Technical Services, 69(3), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J. (2014). Open scholarship and research management. Insights: The UKSG Journal, 27(3), 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayre, F., & Riegelman, A. (2019). Replicable services for reproducible research: A model for academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 80(2), 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, R., & Housewright, R. (2010). US faculty survey 2009: Key insights for libraries, publishers, and societies (pp. 1–35). Ithaka S+R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R. E., Murphy, J. A., Thayer-Styes, C., Buckley, C. E., & Shelley, A. (2023). Exploring faculty perspectives on open access at a medium-sized, American doctoral university. Insights: The UKSG Journal, 36(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R. E., Scott, M., Rawlins, B., & Skaggs, L. (2025a). Sailing into and against the wind: Principled opposition to and acceptance of transformative agreements. Presentation given at the Charleston Conference in Charleston, SC on 6 November 2025. Faculty and Staff Publications—Milner Library. Available online: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/fpml/289 (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Scott, R. E., & Shelley, A. (2023). ‘Having a textbook locks me into a particular narrative’: Affordable and open educational resources in music higher education. Notes, the Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association, 79(3), 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R. E., Shelley, A., Buckley, C. E., Thayer-Styes, C., & Murphy, J. A. (2025b). “I’ll wait zero seconds”: Faculty perspectives on serials access, sharing, and immediacy. College & Research Libraries, 86(1), 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A., Malik, A., & Adnan, R. (2025). Evolution of research data management in academic libraries: A review of the literature. Information Development, 41(2), 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaggs, L., & Scott, R. E. (2025). From negotiating to assessing impact: Centering student authors in open access agreements. Presentation given at Electronic Resources & Libraries. Available online: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/fpml/261 (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Skaggs, L., Scott, R. E., & Cilento, C. (2026). Not just monetary: Arts and humanities scholars’ perspectives on the costs of open access publishing. College & research libraries. Available online: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/fpml/268 (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Tavernier, W., & Jamieson, L. M. (2022). Value added: A case study of research impact services. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 22(4), 919–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.-Y., & Chan, E. K. (2020). Supporting scholarly research: Current and new opportunities for academic libraries. Available online: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/lib_pub/163/ (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Willinsky, J. (2005). The unacknowledged convergence of open Source, open access, and open science. First Monday, 10(8). Available online: https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/download/1265/1185?inline=1 (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Zhao, L. (2014). Riding the Wave of open access: Providing library research support for scholarly publishing literacy. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 45(1), 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fiscal Year | Count | Publication Support | Count | Book Subvention | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY19 | 20 | $3268.00 | 6 | $3368.30 | $6636.30 |

| FY20 | 27 | $4948.91 | 5 | $2144.00 | $7092.91 |

| FY21 | 25 | $4624.53 | 6 | $3309.50 | $7934.03 |

| FY22 | 18 | $3773.73 | 6 | $2875.00 | $6648.73 |

| FY23 | 23 | $4811.00 | 2 | $747.05 | $5558.05 |

| FY24 | 24 | $6196.50 | 5 | $1550.00 | $7746.50 |

| FY25 | 30 | $7707.39 | 6 | $3886.60 | $11,593.99 |

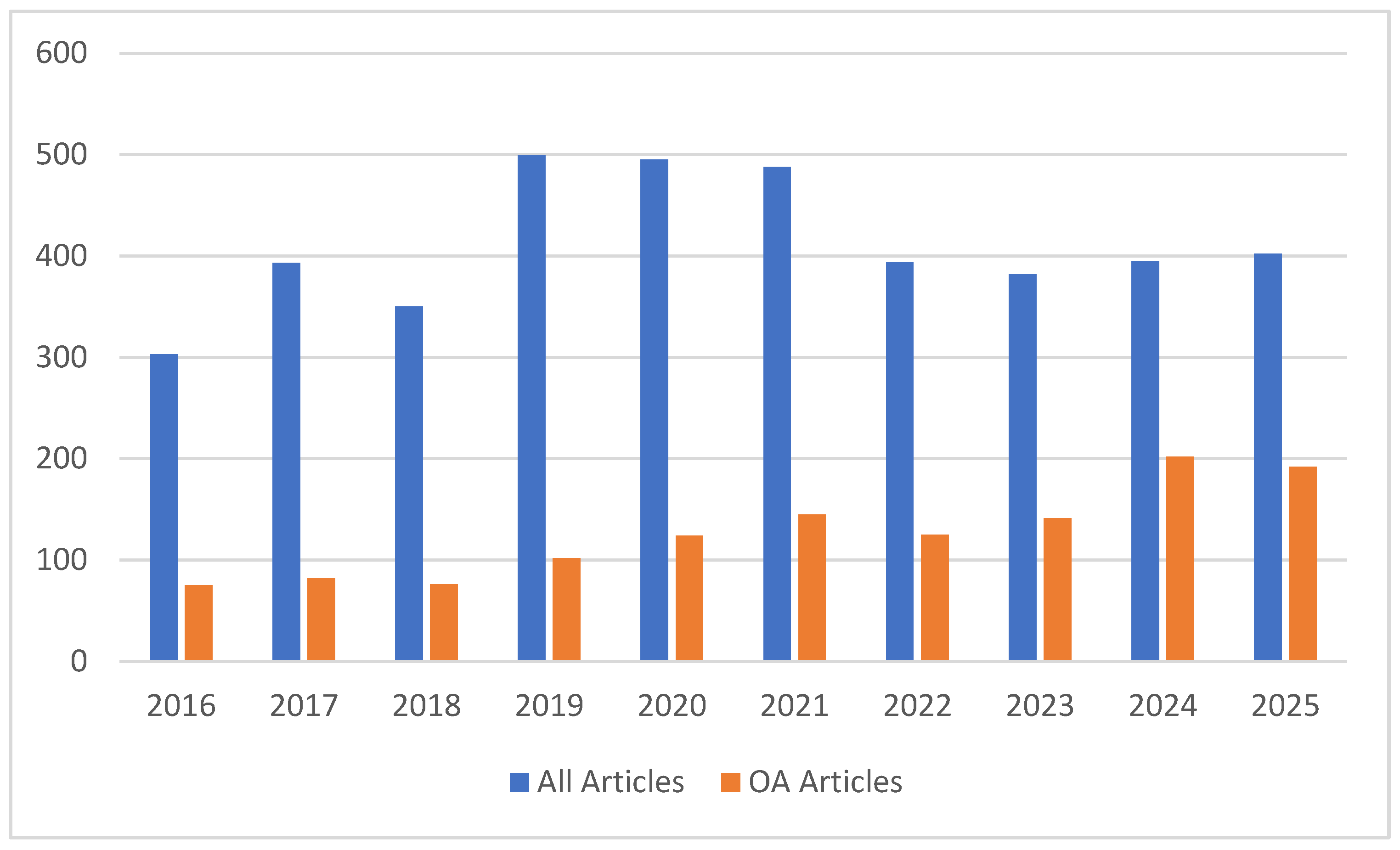

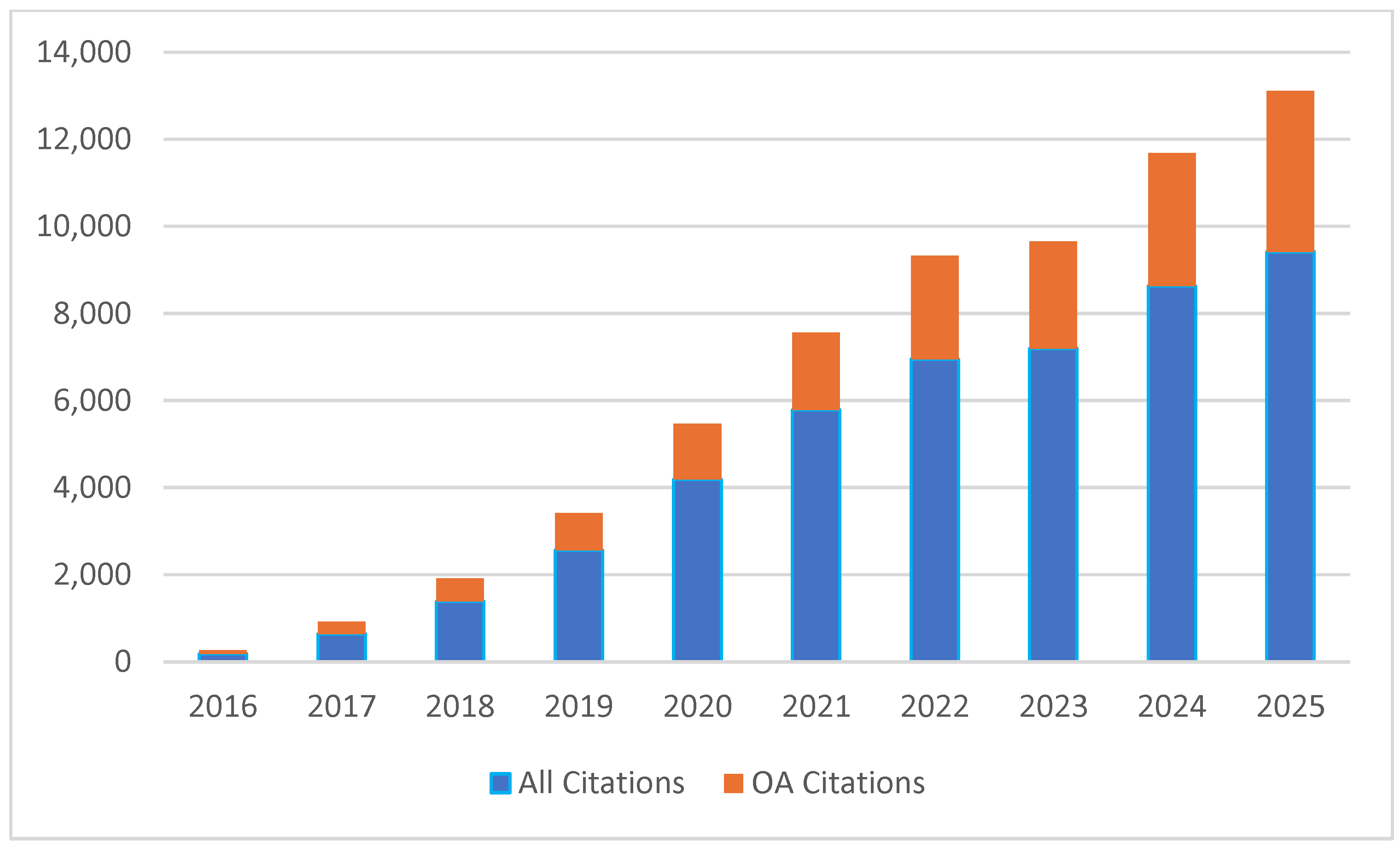

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ISU Authored Articles | 303 | 393 | 350 | 499 | 495 | 488 | 394 | 382 | 395 | 402 |

| All ISU Article Citations | 181 | 643 | 1386 | 2564 | 4187 | 5783 | 6949 | 7193 | 8627 | 9416 |

| OA ISU Authored Articles | 75 | 82 | 76 | 102 | 124 | 145 | 125 | 141 | 202 | 192 |

| OA ISU Article Citations | 89 | 276 | 532 | 853 | 1287 | 1783 | 2381 | 2464 | 3060 | 3695 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Scott, R.E. Supporting the University Research Enterprise via Open Access Publishing: Case Study from a Carnegie Research 2 University. Publications 2026, 14, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications14010010

Scott RE. Supporting the University Research Enterprise via Open Access Publishing: Case Study from a Carnegie Research 2 University. Publications. 2026; 14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications14010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleScott, Rachel Elizabeth. 2026. "Supporting the University Research Enterprise via Open Access Publishing: Case Study from a Carnegie Research 2 University" Publications 14, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications14010010

APA StyleScott, R. E. (2026). Supporting the University Research Enterprise via Open Access Publishing: Case Study from a Carnegie Research 2 University. Publications, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications14010010