Abstract

Background: Focusing scientific research on the health needs of the population could ensure the development of context-specific solutions. In Peru, prioritization has been proposed as a strategy to address this issue. However, the alignment of Peruvian scientific production on tuberculosis (TB) with the national TB research priorities (TBprios) has not been evaluated. Methods: We conducted a bibliometric analysis in Web of Science, Scopus, LILACS, SciELO, and PubMed to identify original articles focused on TB, with at least one author with Peruvian affiliation. Then, we reviewed the general objectives of each study included and verified their alignment with any TBprios. Results: We found that 73% of Peruvian scientific articles were aligned with some of the national research priorities on TB, especially those related to epidemiology and diagnostics, although no increased trends in alignment were identified across the study period. In addition, in an exploratory analysis we found that fewer than 20% of aligned studies reported receiving national funding. Conclusion: Substantial alignment was observed between the research outputs identified and TBprios. Nonetheless, this high level of alignment could also reflect the significance of TB within the social and public health agenda of Peru.

1. Introduction

The End TB Strategy states that research and innovation are crucial pillars to achieve the goal of reducing 95% of deaths and 90% of new cases of tuberculosis (TB) by the year 2035 (World Health Organization, 2015). However, engaging in scientific outputs without a common direction may lose sight of the main health needs of the population, and thus establishment of national research priorities is essential to promote cohesion to common objectives and distribute intellectual and financial resources appropriately (Chalmers et al., 2014).

Currently, scientific production on TB is increasing broadly worldwide (Ekenoğlu Merdan & Etiz, 2022), including highly specialized topics such as the study of genes (Sugimoto et al., 2012) and molecular targets (Wang et al., 2025), or even studies lacking good scientific practice (Garcia-Solorzano et al., 2025). However, this increase might not necessarily be in alignment with the main health problems faced by TB patients. For instance, a study in Cambodia (Boudarene et al., 2017) found that only 29% of TB-related scientific output was aligned with national research priorities. Similarly, in Brazil, researchers were found to adjust their research agendas to meet public policy demands without entirely abandoning their own scientific interests. It was also found that some researchers adapted their research lines to the demands of public policies, without completely abandoning their own scientific interests (Nishida & Teixeira, 2022).

In Peru, strategic efforts to improve population health are guided by the identification of national health priorities and national health research priorities. National health priorities refer to diseases or conditions identified as critical for improving the overall health of the national population (Ministerio de Salud del Perú, 2024). On the other hand, national health research priorities focus on generating locally relevant scientific evidence to support informed decision-making and guide policy development (Instituto Nacional de Salud del Perú, 2024). Aligning research efforts with these national priorities may ensure that scientific inquiry contributes directly to addressing the country’s most pressing health challenges.

In 2018, the National Tuberculosis Research Priorities 2018–2021 (TBprios) were established by a decentralized, national participatory, multisectoral process, to focus research on responding to the principal health needs of Peruvian TB patients. The Child Health and Nutrition Initiative (CHNRI) methodology (Rudan et al., 2008) was applied to TBprios and involves setting important goals and their related research priorities which may provide more appropriate results for a specific geographic area. This methodology has been used by 18% of Latin America and the Caribbean countries to establish their research priorities (McGregor et al., 2014).

The TBprios framework comprises strategic objectives and research necessities. Strategic objectives represent broad goals aimed at addressing critical gaps in TB prevention, epidemiology-diagnostics, and treatment, while research necessities refer to specific areas of inquiry required to generate evidence that supports the achievement of these objectives. The strategic objectives of the TBprios framework include: (a) early detection and diagnosis of TB in all its forms to enable timely initiation of treatment, with emphasis on high-risk populations and priority geographic areas (epidemiology-diagnostic priorities); (b) prevention of TB transmission and disease progression through improved contact investigation and latent TB infection treatment (prevention priorities); and (c) improved treatment success by strengthening comprehensive and integrated care centered on individuals affected by TB (treatment priorities). The diagnostic objective (a) includes four research necessities, while the prevention and treatment objectives (b and c) include three (Ministerio de Salud del Perú, 2018).

Notwithstanding, little is known about the utility of this strategy. Although prioritization strategies have been used in several countries (Lestari et al., 2023), assessment of the posterior alignment is usually not performed. Nonetheless, confidence in this strategy has been renewed in Peru for the 2022–2025 period (Ministerio de Salud del Perú, 2022).

Following the conclusion of the timeframe of the 2018–2021 TBprios, this study aimed to assess the alignment of Peruvian scientific production with these priorities and characterize aligned studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Search Strategy

We conducted a bibliometric analysis using an advanced search of scientific literature to assess studies published between 2019 and 2022 (one year after the TBprios timeframe). Our search was limited to studies published up to 2022 to avoid overlap with subsequent research prioritization strategies 2022–2025. We collected and analyzed data from publications indexed in the Web of Science (All Databases option, including Web of Science Core Collection, KCI-Korean Journal Database, Research Commons, and SciELO Citation Index), Scopus, LILACS, SciELO and MEDLINE (through PubMed) databases. The search was performed in December 2024.

Advance search strategies for each database were constructed using terms such as “Tuberculosis”, “Mycobacterium tuberculosis”, “Koch disease”, “tuberculoses”, and “TB”. In addition, we limited the search for Peruvian affiliation country, and publication year from 2019 until 2022. The full search strategy is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategies used for databases.

2.2. Selection Criteria

Original articles focused on TB, with at least one author with Peruvian affiliation, were included. Other types of research, such as narrative reviews, editorials, letters, and book chapters, were excluded.

2.3. Procedures

To address the issue of inconsistent metadata across databases, we applied a systematic process of deduplication and reconciliation. First, all records were normalized (titles, authors, journal names, publication years) to achieve a uniform format. Duplicates were then identified primarily through unique identifiers such as DOI, PMID, or ISSN. In cases in which such identifiers were absent, duplicates were detected by matching combinations of title, first author, and year of publication. For records that were highly similar but not identical, a manual review was conducted.

When the same article appeared in more than one database with partially divergent metadata, we established a hierarchy of priority: Scopus and Web of Science were used as the main sources for citation data, PubMed for MeSH terms, and SciELO/LILACS for regional descriptors. Each article was then consolidated into a single “canonical” record containing the most complete and accurate information available.

2.4. Variables and Data Extraction

From each study included we extracted the general objective, year (2019, 2020, 2021, 2022), funding source (National funding, International funding, Both, Not reported), and Scimago quartile (Q1–Q4).

To assess the TBprios, we employed a complementary indicator recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) framework for monitoring health research priority-setting exercises: research production (World Health Organization, 2020). Two authors (FOGS and YAB) reviewed the abstract of each study included and verified their alignment with any TBprios (weighted Cohen’s kappa = 0.78). A study was considered to be aligned when its objective addressed a topic broadly related to any of the TBprios.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed by descriptive analysis using frequency and percentage for all categorial variables. In addition, we present the number of Scopus citations using medians and its respective interval quartile.

We conducted a temporal trend analysis of the different categories of TBprios by publication year. To assess the presence of monotonic trends, we applied the Cochran–Armitage trend test. In addition, to estimate the magnitude of changes over time, we fitted a weighted linear model of proportions, using the total number of observations per year as weights. This approach allowed quantification of the average annual change in percentage points, along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). All the analyses were performed using RStudio (Version 2025.09.0+387).

2.6. Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee at the Universidad Científica del Sur (approval code: N° 302-CIEI-CIENTÍFICA-2024).

3. Results

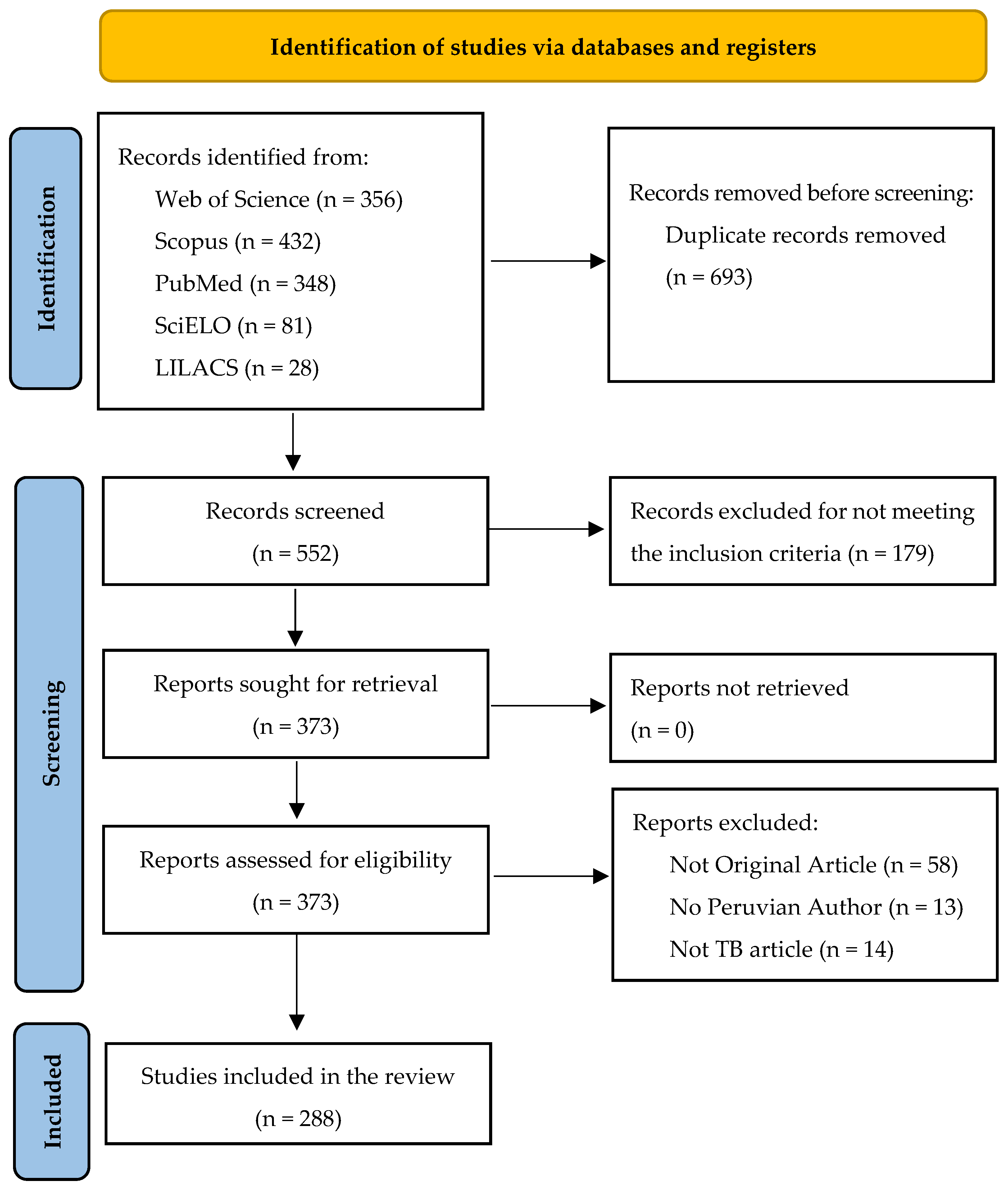

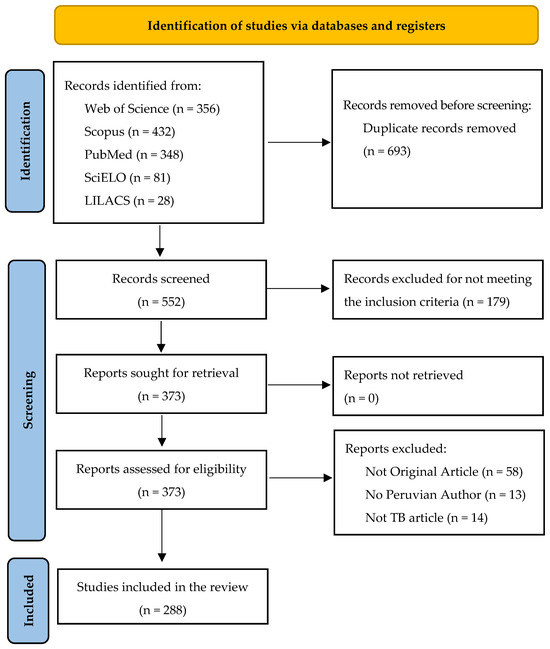

A total of 1245 records were identified through the search strategy. Of these, 522 were screened by title and abstract. Finally, 288 articles were included in the analysis. The full selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

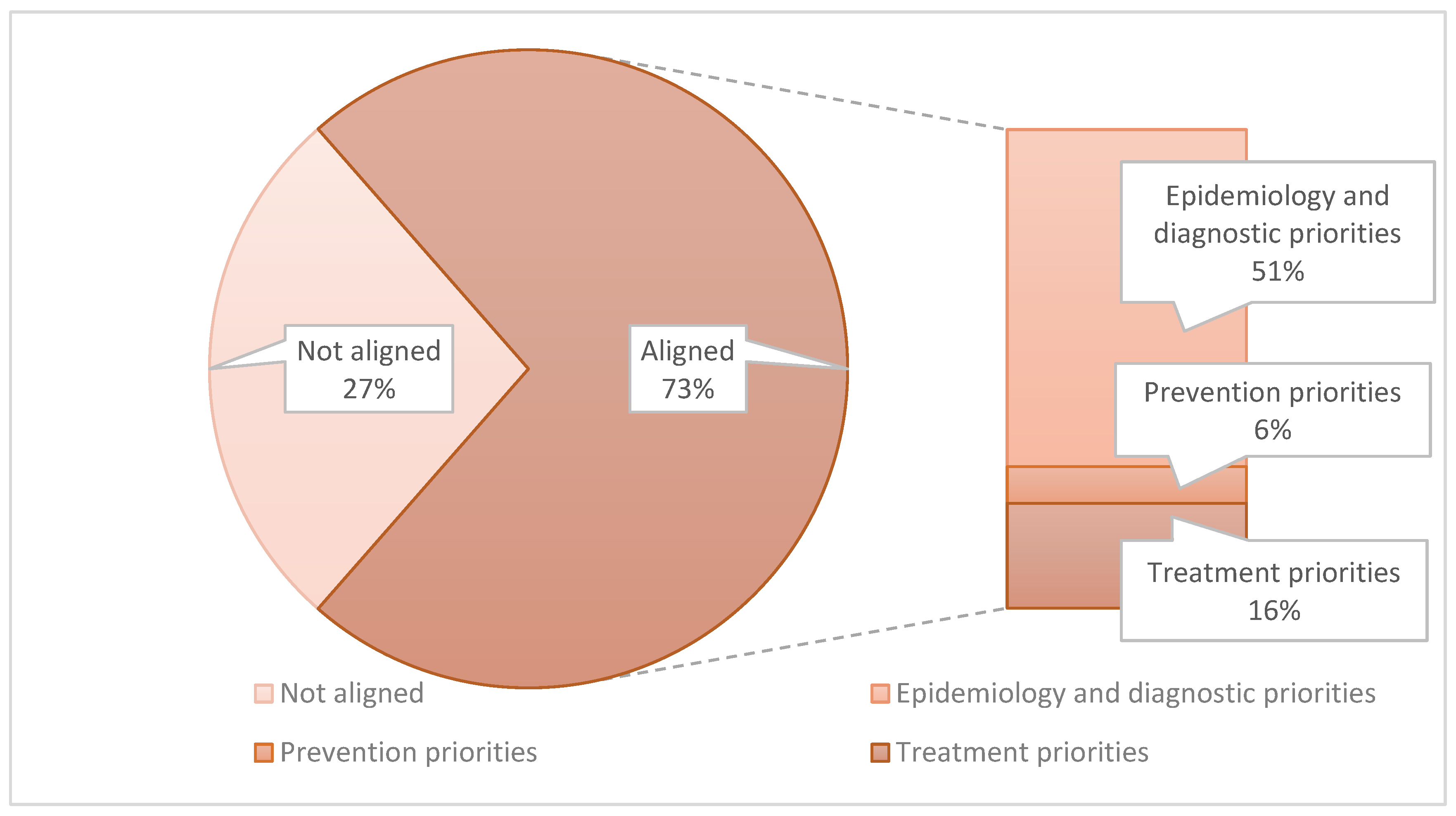

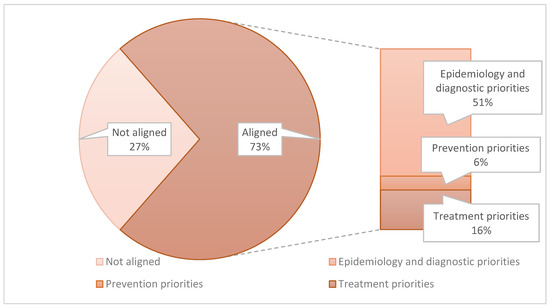

Of these, 73% (n = 210) were aligned with some national TBprios. More than half of the scientific articles included were aligned with epidemiology-diagnostic priorities, mainly related to the identification of risk groups. Of the aligned studies, 148 (51%), 16 (6%), and 46 (16%) studies were aligned with epidemiology-diagnostic, prevention, and treatment priorities, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scientific production on tuberculosis aligned with the National Scientific Production in Tuberculosis.

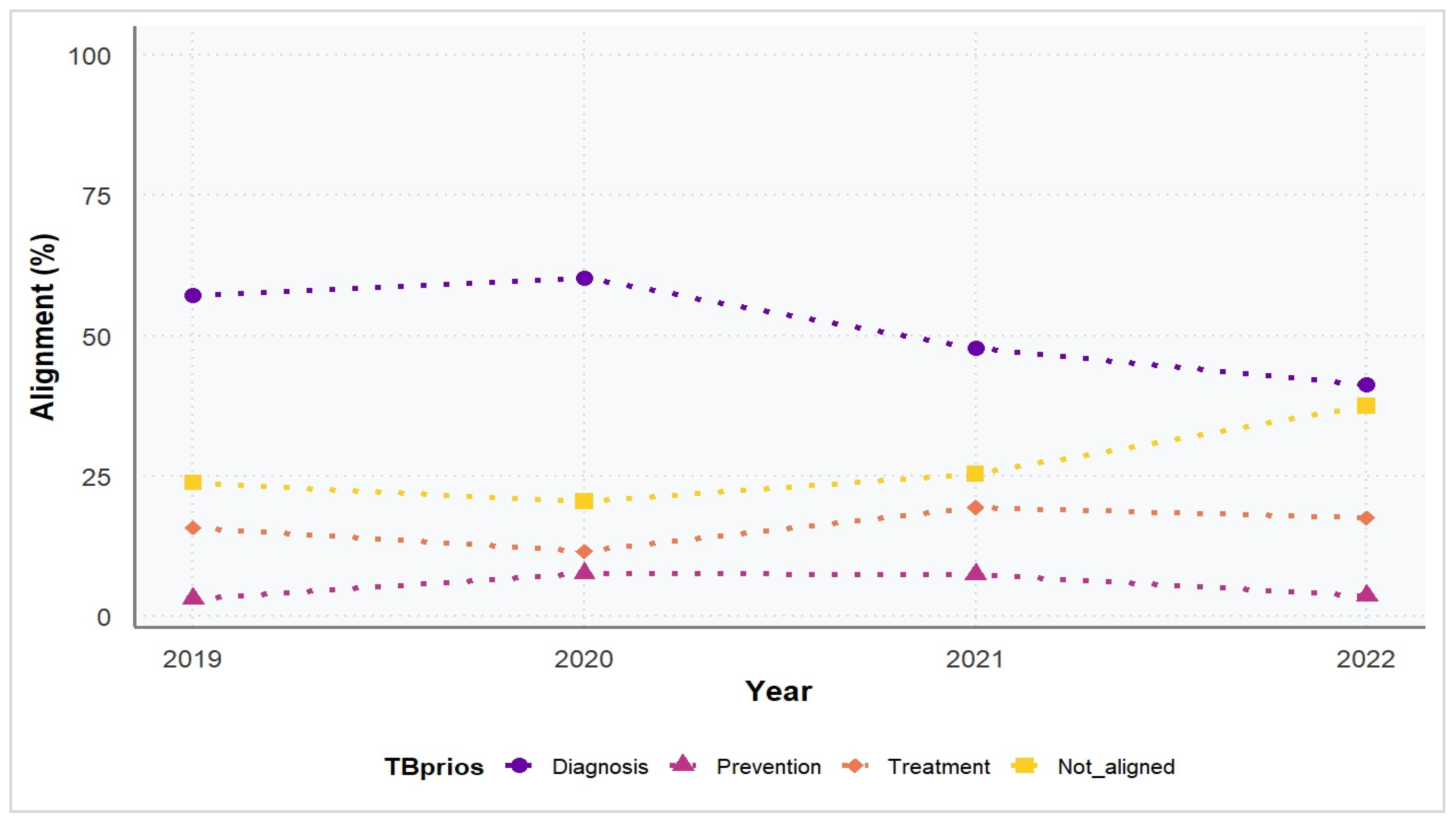

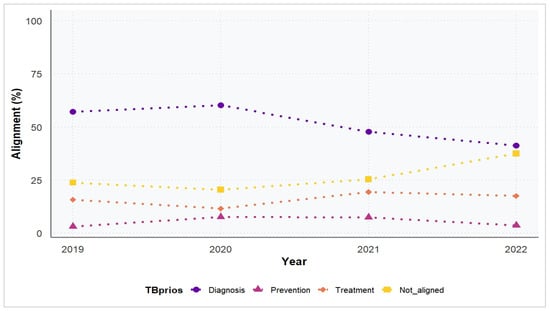

Between 2019 and 2022, a significant decrease in the proportion of studies aligned with the Epidemiology–Diagnostic priorities were observed, falling from 57.1% to 41.2% and corresponding to an average annual reduction of approximately 6 percentage points (95% CI: −10.5 to −2.0; p = 0.018). In contrast, the proportion of research classified as not aligned showed a significant increase, rising from 23.8% in 2019 to 37.5% in 2022, with an average annual increase of nearly 5 percentage points (95% CI: 0.2 to 9.7; p = 0.036). Moreover, there were non-significant variations over the study period for Treatment (p = 0.487) and Prevention (p = 0.980) priorities (Figure 3). Frequencies of alignment with TBprios, disaggregated by year, are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of alignment variation across the study period.

Most studies, including those that were and were not aligned, reported that they were mainly funded by international entities, especially those related to prevention and diagnostic priorities. Among the aligned studies, national funding was reported in 27%, while 16% reported national funding plus international funding (Table 2).

Table 2.

Funding sources related to national research priorities of tuberculosis studies (n = 288).

Aligned and not aligned studies were mainly published in high impact journals, but nearly half of the scientific articles aligned with treatment priorities were published in low quartile or non-quartile journals. Moreover, most of the scientific production on TB was produced with international collaboration, especially studies related to prevention priorities (Table 3).

Table 3.

Impact indicator of national research priorities for tuberculosis (n = 288).

4. Discussion

The main findings of this study show that most original articles on TB, with at least one Peruvian author, were aligned with some of the TBprios, especially those related to epidemiology-diagnostic priorities. However, no increase in trends in alignment were noted across the study period and only a few aligned studies were reported as being conducted with national funding. In addition, there was no clear difference in the number of studies, citations or journal impact, between aligned and not aligned studies.

Although strong alignment with the TBprios was observed, it should be noted that TB in Peru has a historical, cultural, and social importance (Alarcón et al., 2017). Peru has one of the highest incidence rates in Latin America as well as a substantial number of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant cases (World Health Organization, 2023). Since the priorities were established based on the magnitude and impact of TB in Peru, it is expected that, even without explicit reference to TBprios, researchers tend to orient their studies toward this problem. Thus, the alignment proportion identified can be interpreted as a result of the strong connection between the country’s health context and its corresponding priorities, and not necessarily as a deliberate use of the national priorities as a formal guide for research.

This hypothesis could be supported by the fact that a previous study that evaluated scientific production on national research agendas, long before the establishment of the TBprios, showed that TB research accounted for the largest share of scientific output (Romani Romani et al., 2016). Furthermore, alignment with TBprios did not increase over the years analyzed and even decreased over time, as in the case of epidemiology-diagnostic priorities. Additionally, the evaluation of funding showed that most of the research aligned with the TBprios reported having been financed by international entities, with a minority of aligned studies indicating that national funding had been received.

In contrast to our results, a previous study performed in Cambodia (Boudarene et al., 2017) found that less than one third of the TB research output in Cambodia was aligned with national health decisions, and the lowest proportion of alignment accounted for priorities in multidrug-resistant TB and universal access to quality diagnostics and treatment. Other studies have examined broader health research agendas beyond TB. For example, a recent analysis in India (Kumar et al., 2024) showed a striking mismatch between national disease burden and research output, with respiratory diseases representing one of the major disease burdens but making up only 6% of publications. Similarly, in Brazil, another study (Nishida & Teixeira, 2022) that evaluated the impact of the establishment of the National Health Research Priority Agendas on the planning of research by laboratories in the country by qualitative assessment, revealed that the attempt to align studies with priorities was related to a phenomenon of “fitting”, driven by power dynamics involved in the assignment of research funding and the integration into international collaboration networks. In our study, it is not clear whether this “fitting” phenomenon might also have influenced the results obtained.

It is difficult to assess research priorities on guiding scientific production in a specific region for three main reasons. Firstly, the definition of what a “research priority” is may differ. For example, some studies use this term to describe topics that are most frequently published in scientific journals in a specific field (Morán-Mariños et al., 2024). In addition, if research priorities are set using a specific method, the results can vary depending on the method used, since each method has different goals, content, and ways of sharing information and implementation (Reveiz et al., 2013).

Secondly, most countries that establish research priorities often do not report the results of follow-up or implementation strategies, thereby limiting evaluation of their impact on scientific production (McGregor et al., 2014). The implementation phase of priorities is crucial not only to assess the impact but also to promote alignment, improve resource management, and enhance feedback of the process for future prioritization strategies (Chalmers et al., 2014). In the case of Peru, no specific study assessing the implementation of national research priorities was found. Therefore, it is urgent for the Peruvian scientific community to demand a formal implementation strategy. This is especially important considering that research prioritization is still a strategy for 2022–2025 (Ministerio de Salud del Perú, 2022).

Third, along the line of the “fitting” phenomenon, participants of the TBprios establishment process were not publicly available (Ministerio de Salud del Perú, 2018), making it impossible to assess this phenomenon. In addition, it was not feasible to determine the exact time at which the research ideas that led to the articles evaluated in this study were conceived, which could be even earlier than the publication of TBprios. Nonetheless, we considered analyzing publications from the year following the publication of the TBprios and performed the search strategy in 2024 to minimize the possible lag between research conception and publication and to avoid the indexation lag of the articles in the respective database.

Additionally, both the Web of Science and Scopus show regional and disciplinary disparities, with Latin American journals often being underrepresented and English-language outlets disproportionately favored (Asubiaro et al., 2024). To mitigate these issues, we complemented the Web of Science and Scopus with regional sources such as LILACS and SciELO, which allowed capturing a more comprehensive picture of Peruvian scientific production.

Regarding the aligned studies, the epidemiology and diagnostics priorities were the most covered. Not only because of the burden of TB in Peru but also because social determinants, such as poverty, immigration, and lack of access to basic resources, have an impact on the diagnosis and treatment of this disease (Di Gennaro et al., 2017). Moreover, timely and early diagnosis significantly impacts treatment outcomes, increases adherence to treatment, and decreases TB transmissibility to effectively control the disease (Di Gennaro et al., 2022). Therefore, efforts focused on these areas are logical.

The impact of publication of aligned studies showed that the number of citations was quite low, with an average of between 3 and 4 citations. This figure contrasts markedly with the findings of the study by Torres-Pascual et al. (2021), who assessed the scientific production on TB in Latin America from 2009 to 2018 and found an average number of citations ranging from 8.5 to 10.9, depending on whether there was international collaboration. Thus, high alignment with research priorities with limited impact on the generation of new studies, which strengthen the local scientific evidence, could lead to the need to rethink established priorities. However, it should be noted that traditional journal-level measures (such as journal quartile, CiteScore percentile, Scimago Journal Rank) might under-evaluate journal quality as shown in a previous study (Veretennik & Yudkevich, 2023).

A previous study has shown the methodology to assess the role of funding in research by a bibliometric approach (Sousa Vieira & Cerdeira, 2025). In our analysis, only 27% and 16% of the aligned studies reported national and international funding, respectively. Funding for TB research in Peru is primarily distributed through the National Council for Science, Technology, and Technological Innovation (CONCYTEC) and its National Fund for Scientific, Technological, and Technological Development (FONDECYT). In collaboration with the National Institute of Health (INS), CONCYTEC promotes and supports national health research priorities through competitive funding and fostering collaboration between academia and other entities (Ministerio de Salud, 2020). Although almost one third of the aligned studies were funded by national entities, many are highly dependent on foreign funders. Therefore, strategies are necessary to reduce the fragility of the funding structure especially when international funding has been reduced in 2025 (The JAMA Forum, 2025). Nevertheless, it is also important to consider that assessing the effects of funding entities is inherently complex due to the multiple and overlapping sources, types, and scopes of funding, as well as the absence of a clear boundary between funded and “unfunded” research (since internal or implicit support is often not recorded) (Thelwall et al., 2023).

Although we identified that a significant proportion of studies were directly aligned with the priorities set by TBprios, many of the not aligned studies addressed critical issues such as treatment effectiveness and safety, discovery of new targets for treatment and diagnostics, the influence of the sociocultural context in TB patients, and TB/HIV coinfection, which were prioritized by the WHO (Gebreselassie et al., 2019). Likewise, we identified recurring studies related to the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and immunological alterations in patients. In this context, while TBprios broadly coincide with general priority areas of the WHO, such as early detection, diagnosis, and treatment adherence, the national priorities may have been adapted to Peru’s financial and technological limitations, which make certain highly specialized or resource-intensive research areas less feasible. These findings do not imply a negative assessment of non-aligned research but rather underscore the need for national research priorities to be dynamic, inclusive, and continuously informed by emerging scientific evidence.

Unlike the previous period of TBprios (2018–2021), the TBprios for the period 2022–2025 (Ministerio de Salud del Perú, 2022) has doubled the number of strategic objectives. These new priorities include evaluating the effectiveness of preventive measures and the use of technologies in treatment, as well as studying social and cultural barriers to diagnosis and treatment, and their impact on nutrition and mental health. The possibility of reassessing weaknesses and threats in the prioritization process and implementing these priorities should not be limited to passive monitoring of scientific production. It is essential that governing health research bodies take an active role as managers in knowledge generation. This will not only lead to significant improvements in the research process but also in health indicators related to a problem that, beyond its biological nature, is deeply rooted in the historical and social context of inequity in Peru.

There are some limitations to this research that are important to note. First, the Peruvian scientific production analyzed might not include Peruvian authors who identify only with foreign affiliations or who consider themselves independent researchers. Furthermore, studies conducted in Peru might have also been excluded from this analysis if none of their authors had a Peruvian affiliation. Moreover, in Scopus, about 8.4% of records (2000–2020) lacked country affiliation and up to 16% of all records (1900–2023) were labeled as “country-undefined,” although this issue was less pronounced in the Web of Science, both databases may bias country-level bibliometric analyses (Savchenko & Kosyakov, 2022; Liu & Wang, 2025). Despite these restrictions, the strategy employed to characterize scientific production in a specific geographic context, based on affiliation, can be considered a valuable indicator, and this approach is a commonly accepted methodology in bibliometric studies (Glänzel & Schubert, 2005). Second, although Web of Science has improved the collection of funding acknowledgments, important coverage gaps remain across indexes, languages, and document types (Álvarez-Bornstein et al., 2017). In addition, Scopus has been shown to provide funding data with lower accuracy than Web of Science (Liu, 2020); therefore, findings related to funding in this study should be interpreted with caution. Third, although some relevant publications in the grey literature may have been missed, we conducted a comprehensive and advanced search across the largest databases, including regional databases. Finally, we could not compare the list of authors from aligned studies with the list of actors convened for the study prioritization process, due to the lack of publicly available information, which limited exploration of the fitting hypothesis with the established priorities. Future studies should consider leading with these limitations and assessing how aligned scientific production influences health decision-making, particularly in the development of national TB control programs and policies.

5. Conclusions

A substantial percentage of TB articles of Peruvian scientific production address national priority areas. However, temporal trends and funding patterns reveal gaps that warrant further exploration. Additionally, the importance of TB within the social and public health agenda of Peru should be considered when interpreting these findings. This analysis offers a methodological approach that may be applicable to other research fields and settings seeking to evaluate alignment between research outputs and priority-setting frameworks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/publications13040047/s1, Table S1: TBprios alignment across the study period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.O.G.-S. and Y.A.-B.; methodology, F.O.G.-S., Y.A.-B., and L.L.; formal analysis, F.O.G.-S.; resources and data curation, S.S.-M. and O.F.-Z.; All authors write the original draft; supervision, F.O.G.-S. and L.L.; project administration, F.O.G.-S. and Y.A.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| TBprios | Peruvian National Tuberculosis Research Priorities |

References

- Alarcón, V., Alarcón, E., Figueroa, C., & Mendoza-Ticona, A. (2017). Tuberculosis en el Perú: Situación epidemiológica, avances y desafíos para su control. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Publica, 34(2), 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asubiaro, T., Onaolapo, S., & Mills, D. (2024). Regional disparities in Web of Science and Scopus journal coverage. Scientometrics, 129(3), 1469–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Bornstein, B., Morillo, F., & Bordons, M. (2017). Funding acknowledgments in the Web of Science: Completeness and accuracy of collected data. Scientometrics, 112(3), 1793–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudarene, L., James, R., Coker, R., & Khan, M. S. (2017). Are scientific research outputs aligned with national policy makers’ priorities? A case study of tuberculosis in Cambodia. Health Policy and Planning, 32(Suppl. S2), ii3–ii11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, I., Bracken, M. B., Djulbegovic, B., Garattini, S., Grant, J., Gülmezoglu, A. M., Howells, D. W., Ioannidis, J. P. A., & Oliver, S. (2014). How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. The Lancet, 383(9912), 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, F., Lattanzio, R., Guido, G., Ricciardi, A., Novara, R., Patti, G., Cotugno, S., De Vita, E., Brindicci, G., Mariani, M. F., Ronga, L., Santoro, C. R., Romanelli, F., Stolfa, S., Papagni, R., Bavaro, D. F., De Iaco, G., & Saracino, A. (2022). Predictors for pulmonary tuberculosis outcome and adverse events in an Italian referral hospital: A nine-year retrospective study (2013–2021). Annals of Global Health, 88(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, F., Pizzol, D., Cebola, B., Stubbs, B., Monno, L., Saracino, A., Luchini, C., Solmi, M., Segafredo, G., Putoto, G., & Veronese, N. (2017). Social determinants of therapy failure and multi drug resistance among people with tuberculosis: A review. Tuberculosis, 103, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekenoğlu Merdan, Y., & Etiz, P. (2022). A scopus-based bibliometric analysis of global tuberculosis publications: 1849–2020. Turk Toraks Dergisi (Turkish Thoracic Journal), 23(3), 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Solorzano, F. O., De la Cruz Anticona, S. M., Pezua-Espinoza, M., Chuquispuma Jesus, F. A., Sanabria-Pinilla, K. D., Chavez Veliz, C., Huayta-Alarcón, V. A., Mayta-Tristan, P., & Lecca, L. (2025). Analyzing the drivers behind retractions in tuberculosis research. Publications, 13(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreselassie, N., Falzon, D., Zignol, M., & Kasaeva, T. (2019). Tuberculosis research questions identified through the WHO policy guideline development process. European Respiratory Journal, 53(3), 1802407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glänzel, W., & Schubert, A. (2005). Analysing scientific networks through co-authorship. In H. F. Moed, W. Glänzel, & U. Schmoch (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative science and technology research: The use of publication and patent statistics in studies of S&T systems (pp. 257–276). Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Salud del Perú. (2024). Prioridades nacionales de investigación en salud. [Internet]. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/38070-prioridades-nacionales-de-investigacion-en-salud (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Kumar, A., Koley, M., Yegros, A., & Rafols, I. (2024). Priorities of health research in India: Evidence of misalignment between research outputs and disease burden. Scientometrics, 129(3), 2433–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, T., Fuady, A., Yani, F. F., Putra, I., Pradipta, I. S., Chaidir, L., Handayani, D., Fitriangga, A., Loprang, M. R., Pambudi, I., Ruslami, R., & Probandari, A. (2023). The development of the national tuberculosis research priority in Indonesia: A comprehensive mixed-method approach. PLoS ONE, 18(2), e0281591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W. (2020). Accuracy of funding information in Scopus: A comparative case study. Scientometrics, 124(2), 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., & Wang, H. (2025). Red alert: Millions of “homeless” publications in Scopus should be resettled. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 76(10), 1283–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, S., Henderson, K. J., & Kaldor, J. M. (2014). How are health research priorities set in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published reports. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud. (2020). Decreto legislativo N.° 1504. [Internet]. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/presidencia/normas-legales/576178-1504 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ministerio de Salud del Perú. (2018). Resolución ministerial N.° 591-2018/MINSA. [Internet]. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/normas-legales/1462-591-2018-minsa (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ministerio de Salud del Perú. (2022). Resolución ministerial N.° 729-2022-MINSA. [Internet]. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/normas-legales/3495599-729-2022-minsa (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ministerio de Salud del Perú. (2024). Resolución ministerial N.° 184-2024-MINSA. [Internet]. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/normas-legales/5364816-184-2024-minsa (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Morán-Mariños, C., Visconti-Lopez, F. J., Espiche, C., Llanos-Tejada, F., Villanueva-Villegas, R., Casanova-Mendoza, R., & Bernal-Turpo, C. (2024). Research priorities and trends in pulmonary tuberculosis in Latin America: A bibliometric analysis. Heliyon, 10(15), e34828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, L., & Teixeira, M. d. O. (2022). Encaixando agendas: Análise dos efeitos da agenda nacional de pesquisa em saúde em laboratórios de pesquisa biomédica. Revista Tecnologia e Sociedade, 18(52), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reveiz, L., Elias, V., Terry, R. F., Alger, J., & Becerra-Posada, F. (2013). Comparison of national health research priority-setting methods and characteristics in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2002–2012. Revista Panamericana De Salud Publica = Pan American Journal of Public Health, 34(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Romani Romani, F. R., Roque Henríquez, J., Vásquez Loarte, T., Mormontoy Calvo, H., & Vásquez Soplopuco, H. (2016). Análisis bibliométrico de la producción científica sobre las agendas nacionales de investigación en el Perú 2011–2014. Anales de La Facultad de Medicina, 77(3), 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rudan, I., Gibson, J. L., Ameratunga, S., El Arifeen, S., Bhutta, Z. A., Black, M., Black, R. E., Brown, K. H., Campbell, H., Carneiro, I., Chan, K. Y., Chandramohan, D., Chopra, M., Cousens, S., Darmstadt, G. L., Meeks Gardner, J., Hess, S. Y., Hyder, A. A., Kapiriri, L., … Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative. (2008). Setting priorities in global child health research investments: Guidelines for implementation of CHNRI method. Croatian Medical Journal, 49(6), 720–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, I., & Kosyakov, D. (2022). Lost in affiliation: Apatride publications in international databases. Scientometrics, 127(6), 3471–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa Vieira, E., & Cerdeira, J. (2025). Research on neonatal conditions in Africa: Funding activities from a bibliometric perspective. Publications, 13(2), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, A., Krull, S., Nomura, S., Morita, T., & Tsubokura, M. (2012). The voice of the most vulnerable: Lessons from the nuclear crisis in Fukushima, Japan. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(8), 629–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The JAMA Forum. (2025). Cutting the NIH—The $8 trillion health care catastrophe. JAMA Health Forum. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2834949 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Thelwall, M., Simrick, S., Viney, I., & Oancea, A. (2023). What is research funding, how does it influence research, and how is it recorded? Key dimensions of variation. Scientometrics, 128(11), 6085–6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Pascual, C., Sánchez-Pérez, H. J., & Àvila-Castells, P. (2021). Geographical distribution and international collaboration of Latin American and Caribbean scientific publications on tuberculosis in Pubmed. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública, 38(1), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretennik, E., & Yudkevich, M. (2023). Inconsistent quality signals: Evidence from the regional journals. Scientometrics, 128(6), 3675–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q., Fu, H., Zhang, Y., Zhang, M., Xu, J., & Fu, J. (2025). Bibliometric and visualization analysis of DprE1 inhibitors to combat tuberculosis. Drug Design, Development and Therapy, 19, 2577–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2015). The end TB strategy. [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/the-end-tb-strategy (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2020). A systematic approach for undertaking a research priority-setting exercise: Guidance for WHO staff. World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/334408 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2023). Global tuberculosis report 2024. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024/tb-disease-burden/1-3-drug-resistant-tb (accessed on 22 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).