Abstract

The Research Integrity Risk Index (RI2), introduced as a tool to identify universities at risk of compromised research integrity, adopts an overly reductive methodology by combining retraction rates and delisted journal proportions into a single, equally weighted composite score. While its stated aim is to promote accountability, this commentary critiques the RI2 index for its flawed assumptions, lack of empirical validation, and disproportionate penalization of institutions in low- and middle-income countries. We examine how RI2 misinterprets retractions, misuses delisting data, and fails to account for diverse academic publishing environments, particularly in Indonesia, where many high-performing universities are unfairly categorized as “high risk” or “red flag.” The index’s uncritical reliance on opaque delisting decisions, combined with its fixed equal-weighting formula, produces volatile and context-insensitive scores that do not accurately reflect the presence or severity of research misconduct. Moreover, RI2 has gained significant media attention and policy influence despite being based on an unreviewed preprint, with no transparent mechanism for institutional rebuttal or contextual adjustment. By comparing RI2 classifications with established benchmarks such as the Scimago Institution Rankings and drawing from lessons in global development metrics, we argue that RI2, although conceptually innovative, should remain an exploratory framework. It requires rigorous scientific validation before being adopted as a global standard. We also propose flexible weighting schemes, regional calibration, and transparent engagement processes to improve the fairness and reliability of institutional research integrity assessments.

1. Introduction

In May 2025, a preprint by Meho (2025a) introduced the Research Integrity Risk Index (RI2), a composite metric developed to identify universities that exhibit bibliometric patterns suggestive of strategic manipulation or potential misconduct (Meho, 2025a). The index relies on two main indicators: retraction risk and delisted journal risk. Retraction risk is defined as the number of retracted articles per 1000 publications, specifically targeting retractions due to scientific misconduct, such as fabrication, plagiarism, or peer-review manipulation, over a two-year reference period (2022–2023). These retraction data are sourced from Retraction Watch, Medline, and Web of Science and are matched with institutional publication records in Scopus.

Delisted journal risk refers to the proportion of an institution’s publications that appeared in journals delisted from Scopus or Web of Science during the subsequent two-year window (2023–2024). These two indicators are then normalized using a min–max scaling approach and averaged to produce the composite RI2 score. Institutions are ranked accordingly and categorized into one of five risk tiers based on their percentile ranking: Red Flag (≥95th Percentile), High Risk (90–94.9th), Watch List (75–89.9th), Normal Variation (50–74.9th), And Low Risk (<50th).

Although the RI2 methodology is openly described on its website (Meho, 2025b), it suffers from fundamental flaws in conceptual framing and contextual application. The scoring fails to distinguish between journals delisted for minor editorial issues versus systemic fraud, and it ignores how retractions often occur in journals with higher integrity standards. By flattening these nuances into binary risk labels, the index penalizes universities that are more engaged in high-quality and high-visibility publishing ecosystems. This commentary examines the consequences of applying such a reductive framework, particularly for institutions in developing countries, and calls for an immediate suspension of the RI2 index until it undergoes proper peer review and methodological refinement.

2. The Mislabeling of Indonesia’s Academic Leaders

The RI2 index places several of Indonesia’s most reputable academic institutions into stigmatizing categories, labeling Bina Nusantara University, Universitas Airlangga, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Universitas Hasanuddin, and Universitas Sebelas Maret as “Red Flag” institutions, while Universitas Diponegoro, Brawijaya University, and Padjadjaran University are marked as “High Risk.” Furthermore, the so-called “Watch List” includes the University of Indonesia, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, Bandung Institute of Technology, Bogor Agricultural University, and Gadjah Mada University. These universities represent the backbone of Indonesian higher education and are consistently recognized for their scientific productivity, international collaborations, and contributions to national development.

In sharp contrast to the RI2 classification, the 2025 Scimago Institution Research Ranking places these very same institutions at the top of Indonesia’s academic hierarchy: University of Indonesia ranks first, followed by Gadjah Mada University, Bogor Agricultural University, Universitas Islam Negeri Ar-Raniry, Diponegoro University, Universitas Airlangga, Syiah Kuala University, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Universitas Hasanuddin, and Universitas Sebelas Maret (SCImago, 2025). This enormous deviation between internationally validated research productivity metrics and the RI2 risk labeling is not only statistically suspect—it is a methodological anomaly that discredits the integrity of the RI2 scoring system itself. Rather than revealing genuine institutional risks, the RI2 classification exposes its own flawed assumptions and failure to account for academic excellence contextualized within a national and regional research ecosystem.

3. Flawed Assumptions and the Misuse of Retractions and Delisted Journal Data

The RI2 index fundamentally misinterprets the meaning and implications of retractions. It assumes that retractions are clear indicators of scientific misconduct. However, in practice, many retractions arise from the responsible behavior of journals that maintain rigorous editorial policies and respond effectively to post-publication concerns. These retractions often reflect a functioning and transparent system of quality control, not fraud. Penalizing institutions for participating in this corrective process is both counterintuitive and harmful. Paradoxically, the very universities that engage with high-quality, high-impact journals—where retractions are more likely due to heightened scrutiny—are marked as high risk, thereby discouraging researchers from publishing in reputable venues.

Further compounding this issue is the RI2 index’s treatment of delisted journals. It treats any publication in a journal that was later removed from Scopus or Web of Science as a liability, regardless of the quality of the specific article. This blanket approach ignores important distinctions. If Scopus retains access to a specific article, it suggests that the publication met minimum quality standards even if the journal as a whole was later delisted. Retroactively discrediting such articles is unjustified and misleading. Moreover, the index fails to address the more insidious threat posed by semi-predatory journals that have never been indexed and therefore escape detection. These journals operate outside the radar of major indexing bodies, yet they continue to proliferate unchecked.

The absence of a universally accepted definition of predatory publishing further undermines the credibility of RI2’s approach. The index resurrects a blacklist mentality reminiscent of Beall’s List—a system that was ultimately discredited for causing collateral damage, especially to legitimate but emerging journals in the Global South. In a large-scale qualitative review, researchers analyzed 280 publications discussing predatory publishing and found that Beall’s influence continues to dominate the discourse (Kimotho, 2019). Many of these works—122 of them—uncritically merged the concept of predatory publishing with open access, leading to widespread prejudice against the open access movement as a whole (Krawczyk & Kulczycki, 2021). This conflation has had harmful consequences, unjustly stigmatizing legitimate journals and perpetuating a narrow view of scholarly publishing. As Petrovskaya and Zendle (2022) argue, applying broad and punitive classifications without context leads to more harm than good (Petrovskaya & Zendle, 2022). The RI2 methodology, by reviving such flawed logic, imposes stigmas and misrepresents research integrity, particularly for institutions operating under constrained academic environments.

4. Volatile Scores and the Pitfall of Equal Weighting

One of the most problematic elements of the RI2 methodology lies in its equal weighting of two fundamentally different indicators: the retraction rate and the delisted journal rate. While this design choice may appear to enhance interpretability, it introduces a serious imbalance in how research integrity risks are quantified. Retractions typically reflect isolated, well-documented instances of research misconduct or significant methodological failure. In contrast, delisted journal status often stems from broader editorial issues, shifting indexing criteria, or technical noncompliance—factors that can affect entire volumes of publications regardless of the individual articles’ scientific merit.

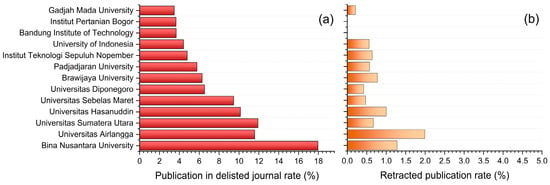

This imbalance becomes particularly evident in Indonesia, where the delisted journal rate at certain institutions, such as Bina Nusantara University, exceeds 17%, while retraction rates remain below 2% (Figure 1). Because RI2 treats both components equally in its composite score, institutions with many publications in delisted journals are disproportionately penalized—even when their record on actual retractions remains relatively clean. This asymmetry may help explain why several of Indonesia’s leading research universities have been classified as “Red Flag” or “High Risk” institutions.

Figure 1.

Comparison of publication rates in delisted journals (a) and retracted publication rates (b) among Indonesian universities flagged by RI2 (Meho, 2025b). The scales differ between the two axes: the delisted journal rate is shown on a 0–20% scale, while the retracted publication rate is plotted on a 0–5% scale.

The problem is further compounded by the assumption that journal delisting—particularly from widely used indexing databases—necessarily signals ethical or scientific failure. Recent cases suggest otherwise. For instance, the journal Nurture was delisted in early 2025, prompting sharp criticism from its editorial board, who described the process as opaque and unilateral (Ahmad, 2025). An editorial published in the delisted journal emphasized that the Scopus Content Selection and Advisory Board (CSAB) did not provide clear feedback or allow the journal to respond to the concerns that triggered delisting. The author argues that such delisting mechanisms often lack accountability and disproportionately impact journals from the Global South (Ahmad, 2025). Yet, under RI2’s design, the presence of Nurture-indexed articles in an institution’s publication record automatically inflates its integrity risk—regardless of the articles’ quality or the circumstances behind the journal’s removal.

This practice creates a flawed dynamic: institutions are penalized not for research misconduct but for having published in journals that were delisted after the fact—possibly without a fair process or substantive justification. Worse still, RI2 may overlook institutions that publish extensively in borderline or low-quality journals that have not yet been delisted, effectively shielding them from scrutiny simply because their publishing venues remain indexed. The scoring’s reliance on delisting status as a proxy for integrity creates unstable and potentially misleading scores. To address this, it would be more appropriate for RI2 to adopt a weighted model—for example, assigning 70% of the score to retractions and 30% to delisted journal publications—to better reflect the relative severity and directness of each signal. However, even this improvement must be applied with flexibility. In high-income or research-intensive countries, where access to reputable journals and robust editorial systems is more evenly distributed, a 50:50 weighting may still offer meaningful discrimination. Conversely, in low- and middle-income contexts, where researchers may face structural constraints, heavier emphasis on verifiable retractions would be more equitable. In other words, weighting schemes should not be fixed globally, but calibrated to reflect publishing realities and structural conditions across regions. More importantly, institutions should be allowed to engage with the scoring process through rebuttals, context-specific disclosures, or audit mechanisms that distinguish misconduct from structural publishing limitations.

5. Global Metric, Local Blindness: RI2’s Design Without Validation

Another concern about the RI2 index is its lack of methodological validation and contextual sensitivity. There is no evidence that its developers undertook external benchmarking with alternative research integrity indicators—such as correction notices, expressions of concern, or institutional investigations—or incorporated qualitative or mixed-method validation through interviews with ethics boards, editorial committees, or researchers impacted by retractions or delisting. As a result, RI2 remains a desk-constructed metric that reduces complex, nuanced academic behaviors into simplistic, binary risk signals.

This flaw mirrors long-standing critiques in global development and public health measurement. For instance, a well-established index such as the Socioeconomic Development Index (SDI) is reported to fail in capturing crucial structural elements like transportation infrastructure and urbanization (You et al., 2020). Even though the SDI is widely used in international benchmarking, it remains the subject of active refinement, revealing that scientific indices must continuously evolve to reflect ground realities. Similarly, another study addressed the inadequacy of conventional socioeconomic status tools in public health by developing the Socioeconomic Status Composite Scale, specifically designed to capture the multidimensional realities in low- and middle-income countries (Sacre et al., 2023). Their validation demonstrated the importance of context-aware, empirically tested tools (You et al., 2020; Sacre et al., 2023).

These lessons are directly relevant to the RI2 index, which applies equal weighting to retraction rates and delisted journal proportions without accounting for how these factors manifest differently across global academic systems. In Indonesia and comparable settings, researchers often face limited funding, unaffordable article processing charges (APCs), and bureaucratic incentives tied to publication counts—conditions that may drive publication in affordable local journals, some of which are later delisted by indexing databases due to editorial or technical concerns unrelated to research misconduct. While it is true that the index may surface symptoms of toxic academic culture, such as output-driven incentives, its current design creates a false equivalence.

6. Harmful Impact and Media Exploitation

The RI2 index’s reach extends well beyond the academic domain, exerting an outsized and damaging influence on public perception and policy discourse—especially in Indonesia. Local media outlets, including Tempo and Antara News, were quick to amplify the index’s “red flag” classifications without offering any critical appraisal of its methodological soundness. For instance, Tempo published multiple reports, including a government response that emphasized the need for impactful research but failed to challenge the validity of the RI2 methodology (Shabrina, 2025). Another article relayed Universitas Sebelas Maret’s explanation for being labeled “Red Flag,” which cited technicalities like legacy publications in discontinued journals—yet still lacked a robust critique of the index itself (Ryanthie, 2025). Antara News similarly urged higher education institutions to focus on impactful publications but offered no meaningful scrutiny of the index’s flawed assumptions (Muhamad, 2025).

These media narratives contributed to a wave of public distrust toward academic institutions, framing top universities as inherently unethical without addressing the structural and methodological flaws embedded in the RI2 index. This is not merely a case of sensational reporting—it reflects a broader systemic failure to safeguard scientific integrity from unverified bibliometric tools. The traction these stories gained—despite the RI2 index lacking peer-reviewed validation—illustrates how unvetted metrics can distort public discourse and damage institutional reputations. This pattern aligns with findings from our recent review on academic infodemics, which highlighted how the convergence of rapid dissemination platforms, digital media incentives, and artificial intelligence—particularly large language models like ChatGPT—can amplify the spread of unverified or oversimplified academic claims (Iqhrammullah et al., 2025).

Compounding the issue is the highly polished and visually compelling website used to present the RI2 index. The project appears meticulously designed for media appeal, featuring sortable rankings, eye-catching visualizations, and even celebratory banners about its popularity in global headlines. The creators appear more concerned with publicity than academic rigor, positioning media virality as a proxy for scholarly merit. Yet, despite its sweeping implications, the RI2 index has not undergone peer review—a critical ethical lapse. For a metric that aspires to diagnose integrity failures across global academia, its own lack of scrutiny is not only ironic but unacceptable. The danger of this approach lies not just in misclassification but in the legitimization of flawed science through slick presentation and premature publicity.

7. Unintended Consequences in the Global South

The RI2 index fails to acknowledge the socioeconomic and structural constraints that shape academic publishing practices in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In Indonesia, researchers are likely to publish their works in affordable or local journals, many of which are labeled as “lenient” due to less stringent peer-review processes due to limited APC funding and a quantity-over-quality culture. Yet these venues often serve as critical platforms for early-career researchers, regional knowledge exchange, and capacity building in academic communities that are otherwise excluded from elite publishing ecosystems. By stigmatizing universities for having publications in small and lower-tier journals that are prone to delisting from major databases, the RI2 index effectively punishes the structural conditions of academic inequality. Instead of improving integrity, this punitive framing exacerbates the North–South divide, reinforcing a global publishing hierarchy that privileges institutions with access to elite networks and funding.

Even more paradoxically, the index penalizes universities when their researchers publish in high-integrity journals that issue retractions—a process typically reflective of transparency and post-publication oversight. In this way, the RI2 approach creates a perverse incentive to avoid rigorous journals for fear of retraction-based penalties. It fosters a culture of strategic avoidance rather than critical engagement with ethical publishing practices. Indonesia’s academic infrastructure is still evolving, with many national journals striving to meet international standards while serving local research priorities. Blanket penalization undermines these efforts and risks delegitimizing locally relevant scholarship.

The danger of such misapplied metrics is that they steer researchers away from high-stakes, high-quality environments and into an unproductive cycle of publishing merely to avoid scrutiny. This not only weakens research integrity but also suppresses innovation, collaboration, and the very scientific dialogue the RI2 index claims to defend.

8. Concluding Remarks

While the intention behind the RI2 index, to protect and promote research integrity, is admirable in theory, its execution falls short in many key aspects. The methodology it employs is not only underdeveloped and unvalidated by peer review, but it also fails to account for the diverse realities and structural inequalities faced by academic institutions in the Global South. By uniformly treating retractions as indicators of misconduct and penalizing publications in delisted journals without appropriate context, the index fundamentally misrepresents the efforts of institutions striving to contribute to global knowledge under constrained circumstances.

The disproportionate penalization of Indonesia’s top-performing universities—many of which are internationally respected and consistently rank high in globally accepted research performance indices—reveals the dangerous consequences of applying metrics that insufficiently capture contextual complexities. Moreover, the public dissemination of RI2 scores through media channels, in the absence of peer-reviewed validation or methodological criticism, undermines the very integrity the index purports to defend. This not only misinforms the public and erodes trust in science but also demoralizes researchers and institutions already burdened by systemic barriers. Moreover, the index’s influence may extend to how research funding bodies or regulatory agencies interpret institutional integrity. This could inadvertently affect resource allocation, grant eligibility, or compliance monitoring.

It is also deeply concerning that a tool with global implications is based on a single-authored preprint. Evaluating research integrity across hundreds of institutions and dozens of countries demands multinational, interdisciplinary collaboration. Without involving co-authors or experts from diverse academic systems, particularly those in the Global South, the risk of imposing biased interpretations and misjudgments grows exponentially. The lack of collaborative authorship reinforces the impression that the index was developed in isolation, disconnected from the real-world complexities it claims to measure.

To move forward constructively, we acknowledge that RI2 offers an innovative foundation that could enrich how we understand institutional research risk. However, it must remain in the realm of exploratory inquiry, not prematurely deployed as a high-stakes metric in national or global research policy. At minimum, RI2 must undergo formal validation across diverse contexts, including field-level triangulation, comparative benchmarking, and expert consultation. Any composite scoring mechanism should reflect the varying severity and interpretive weight of its components—such as giving greater emphasis to verified retractions over delisting-based penalties, which may arise from editorial or procedural inconsistencies.

We therefore call for the suspension of the RI2 index until its methodology is subjected to rigorous peer review, and until safeguards are in place to prevent its misuse in policy or public discourse. The pursuit of research integrity must be guided by fairness, context sensitivity, and scientific rigor—not by indicators lacking adequate validation for objective use. Integrity cannot be defended by misapplying data in evaluative contexts; it must be upheld through constructive, transparent, and inclusive approaches that recognize the diversity of global academic ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.; validation, D.D.C.H.R. and M.F.M.; formal analysis, M.I.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.; writing—review and editing, D.D.C.H.R. and M.F.M.; supervision, I.A.; funding acquisition, M.F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education Agency (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pendidikan, LPDP) Scholarship Program.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our deep appreciation to the researchers and scientists in Indonesia who continue to strive for excellence in research, often under challenging circumstances. Their dedication, integrity, and contributions to global knowledge are a testament to the strength and resilience of the Indonesian academic community.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APCs | Article processing charges |

| LMICs | Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) |

| RI2 | Research Integrity Risk Index |

| SDI | Socioeconomic Development Index |

References

- Ahmad, S. (2025). Scopus delisting process behind closed doors: A case study of Nurture. Nurture, 19(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqhrammullah, M., Gusti, N., Muzaffar, A., Khader, Y., Maulana, S., Rademaker, M., & Abdullah, A. (2025). Narrative review and bibliometric analysis on infodemics and health misinformation: A trending global issue. Health Policy and Technology, 14(5), 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimotho, S. G. (2019). The storm around Beall’s List: A review of issues raised by Beall’s critics over his criteria of identifying predatory journals and publishers. African Research Review, 13(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, F., & Kulczycki, E. (2021). How is open access accused of being predatory? The impact of Beall’s lists of predatory journals on academic publishing. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meho, L. I. (2025a). Gaming the metrics? Bibliometric anomalies and the integrity crisis in global university rankings. bioRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meho, L. I. (2025b). The Research Integrity Risk Index (RI2): A composite metric for detecting risk profiles. Available online: https://sites.aub.edu.lb/lmeho/methodology/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Muhamad, S. F. (2025). 13 kampus disorot, Kemdiktisaintek imbau publikasi harus berdampak. Antara News. Available online: https://m.antaranews.com/amp/berita/4943737/13-kampus-disorot-kemdiktisaintek-imbau-publikasi-harus-berdampak (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Petrovskaya, E., & Zendle, D. (2022). Predatory monetisation? A categorisation of unfair, misleading and aggressive monetisation techniques in digital games from the player perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 181, 1065–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryanthie, S. (2025). Penjelasan UNS Solo soal penyebab masuk zona merah dalam risiko integritas penelitian. Tempo. Available online: https://www.tempo.co/politik/penjelasan-uns-solo-soal-penyebab-masuk-zona-merah-dalam-risiko-integritas-penelitian-1903644 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Sacre, H., Haddad, C., Hajj, A., Zeenny, R. M., Akel, M., & Salameh, P. (2023). Development and validation of the socioeconomic status composite scale (SES-C). BMC Public Health, 23, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCImago. (2025). Scimago Institutions Ranking 2025. Available online: https://www.scimagoir.com/rankings.php?sector=Higher%20educ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Shabrina, D. (2025). Respons Kemendiktisaintek soal 13 kampus masuk zona risiko riset. Tempo. Available online: https://www.tempo.co/politik/respons-kemendiktisaintek-soal-13-kampus-masuk-zona-risiko-riset-1885508 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- You, Z., Shi, H., Feng, Z., & Yang, Y. (2020). Creation and validation of a socioeconomic development index: A case study on the countries in the Belt and Road Initiative. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).