Tailoring Scientific Knowledge: How Generative AI Personalizes Academic Reading Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

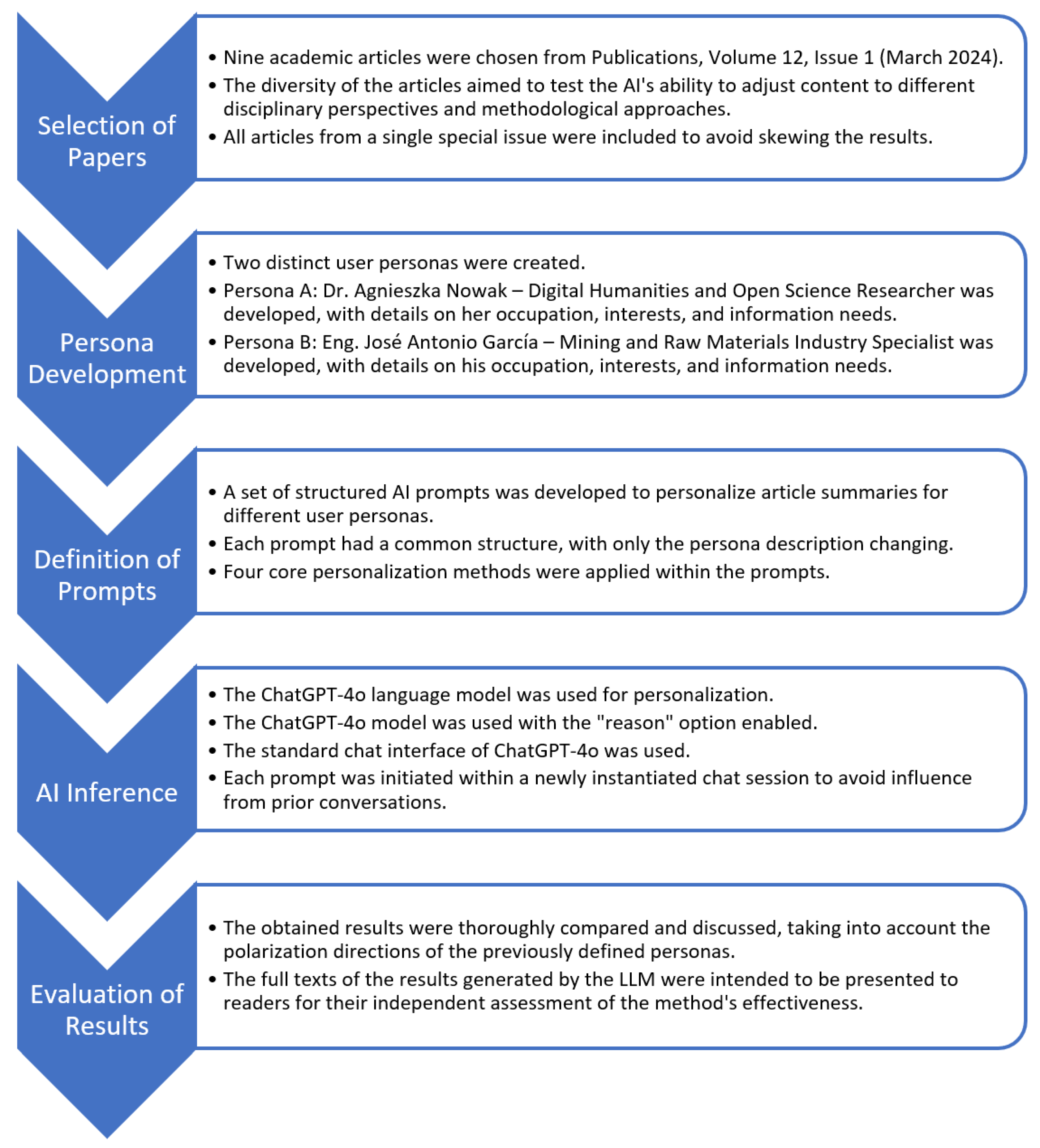

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Selection of Scientific Articles

- Bibliometric Overview of ChatGPT: New Perspectives in Social SciencesThis study conducted a bibliometric analysis of ChatGPT’s impact on social sciences using Scopus data. It identified trends, co-citations, and knowledge gaps, emphasizing AI’s role in academic discourse.

- Benefits of Citizen Science for LibrariesThe article examines the role of citizen science in enhancing library functions. It systematically reviews the literature to outline how libraries can leverage citizen science to promote research engagement.

- Should I Buy the Current Narrative about Predatory Journals? Facts and Insights from the Brazilian ScenarioThis paper challenges prevailing assumptions about predatory journals, advocating for a nuanced debate on publication practices, impact factors, and the evolving landscape of academic publishing.

- FAIRness of Research Data in the European Humanities LandscapeThis article analyzes research data in the humanities, evaluating its openness, compliance with FAIR principles, and representation in repositories. It highlights challenges in accessibility and reusability.

- Reducing the Matthew Effect on Journal Citations through an Inclusive Indexing Logic: The Brazilian Spell ExperienceThis study explores how inclusive indexing in local databases can mitigate the Matthew effect in academic citations, fostering more equitable visibility of journals.

- Does Quality Matter? Quality Assurance in Research for the Chilean Higher Education SystemThe research assesses quality assurance in Chilean universities, revealing that accreditation mainly correlates with publication quantity rather than impact or quality.

- Mining and Mineral Processing Journals in the WoS and Their Rankings When Merging SCIEx and ESCI DatabasesThis article analyzes how merging SCIEx and ESCI databases in JCR 2022 affected journal rankings in the mining and mineral processing field, offering insights for researchers in the industry.

- Tracing the Evolution of Reviews and Research Articles in the Biomedical Literature: A Multi-Dimensional Analysis of AbstractsUsing computational linguistic analysis, this study examines shifts in the writing styles of biomedical research articles and reviews of over three decades.

- Going Open Access: The Attitudes and Actions of Scientific Journal Editors in ChinaThis study investigates Chinese journal editors’ perspectives on open access publishing, analyzing their motivations, barriers, and responses to academic publishing reforms.

3.2. User Persona Development

- Persona A:Dr. Agnieszka Nowak—Digital Humanities and Open Science Researcher

- Occupation: Associate Professor at a university, specializing in digital humanities and social sciences;

- Interests: Open research data, FAIR principles, bibliometrics, open science, ethics of scientific publishing;

- What she looks for in the academic literature? She wants to understand how open science and data accessibility impact humanities and social sciences research. She is also interested in the role of AI (e.g., ChatGPT) in academia and education.

- Persona B:Eng. José Antonio García—Mining and Raw Materials Industry Specialist

- Occupation: Engineer specializing in mining and mineral processing, working for an industrial engineering company;

- Interests: Innovations in the extractive industry, trends in scientific publishing for technical fields, the impact of journal indexing on industry recognition;

- What he looks for in the academic literature?He seeks practical insights into scientific publishing trends in his field, as well as how indexing and citation metrics affect the recognition of technical research.

3.3. Definition of AI Prompts

- Highlighting original fragments of titles and abstracts that are particularly relevant to a given persona, using bold formatting to emphasize crucial aspects.

- Structuring abstracts into bullet-point lists to clearly delineate key research contributions, methodologies, and findings aligned with the persona’s interests.

- Ranking articles based on their relevance to the persona’s expertise, providing a rating with a justification.

- Generating personalized recommendations in the persona’s native language, explaining the article’s relevance and value in their specific research or professional context.

3.4. Implementation of AI

4. Results

| Listing 1. The prompt used to generate the persona-targeted analysis of a scientific article’s title, keywords, and abstract. |

| I need you to analyze a scientific article and highlight sections of interest for two distinct personas, Persona A and Persona B. For each persona, please review the provided title, keywords, and abstract of the scientific article. Identify the parts of the title, keywords, and abstract that would be most relevant and engaging for each persona based on their characteristics. Then, for both Persona A and Persona B, present the title, keywords, and abstract of the article, with the sections of interest bolded. Maintain the original text of the title, keywords, and abstract, only adding bold formatting to emphasize the relevant parts for each persona. Please provide two outputs: one for Persona A and one for Persona B, each containing the title, keywords, and abstract with the relevant sections bolded. Persona A: (…) Persona B: (…) Scientific article: Title: (…) Keywords: (…) Abstract: (…) |

| Listing 2. The prompt employed to gauge potential interest in scientific articles using an LLM and Likert scale ratings. |

| I need you to estimate the potential level of interest for two distinct personas, Persona A and Persona B, in a set of nine scientific articles. For each persona and each of the nine scientific articles (described below by their title and abstract), please provide a rating on a Likert scale indicating the potential level of interest. Likert Scale: 1 – Not at all interested 2 – Slightly interested 3 – Moderately interested 4 – Very interested 5 – Extremely interested For each of the nine articles and for both Persona A and Persona B, please provide a Likert scale rating (1–5) along with a brief justification for your rating. The justification should explain why you believe that persona would have that level of interest, based on the title, and abstract of the article. Please present your output clearly, indicating the persona, the article number (1–9), the Likert scale rating, and the justification for each rating. Remember to consider the characteristics of Persona A and Persona B when evaluating the relevance and appeal of each article’s title and abstract. Persona A: (…) Persona B: (…) Scientific articles: (…) |

| Listing 3. Structured prompt for generating translated, persona-focused summaries of research articles. |

| For each of the nine articles, and for each of the two personas: 1. Identify Key Points: Analyze the article (based on its title and abstract) and determine up to three key points that summarize its main content. 2. Persona-Specific Relevance: Tailor these key points to be relevant and interesting to each persona, considering their described interests and background. Output Format: For each article, present the output in the following format: Article: [Article Title] Persona 1 Perspective: – (English) Point 1 (([Persona 1 Native Language]) Point 1 Translation) – (English) Point 2 (([Persona 1 Native Language]) Point 2 Translation) – (English) Point 3 (if applicable) (([Persona 1 Native Language]) Point 3 Translation (if applicable)) Persona 2 Perspective: – (English) Point 1 (([Persona 2 Native Language]) Point 1 Translation) – (English) Point 2 (([Persona 2 Native Language]) Point 2 Translation) – (English) Point 3 (if applicable) (([Persona 2 Native Language]) Point 3 Translation (if applicable)) Please provide the analysis in the structured format described above. Persona A: (…) Persona B: (…) Scientific articles: (…) |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alvarez, E., Lamagna, F., Miquel, C., & Szewc, M. (2020). Intelligent arxiv: Sort daily papers by learning users topics preference. arXiv, arXiv:2002.02460. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2002.02460 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Antu, S. A., Chen, H., & Richards, C. K. (2023, July 7). Using LLM (Large Language Model) to improve efficiency in literature review for undergraduate research. Workshop on Empowering Education with LLMs-the Next-Gen Interface and Content Generation 2023 co-located with 24th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2023) (pp. 8–16), Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- arXiv. (2021). arXiv statistics: 2021 submissions by area. Available online: https://info.arxiv.org/help/stats/2021_by_area/index.html (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Boboris, K. (2023, November 3). arXiv sets new record for monthly submissions. Available online: https://blog.arxiv.org/2023/11/03/arxiv-sets-new-record-for-monthly-submissions/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Bom, H.-S. H. (2023). Exploring the opportunities and challenges of ChatGPT in academic writing: A roundtable discussion. Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, 57(4), 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornmann, L., & Mutz, R. (2015). Growth rates of modern science: A bibliometric analysis based on the number of publications and cited references. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(11), 2215–2222. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Liu, Z., Huang, X., Wu, C., Liu, Q., Jiang, G., Pu, Y., Lei, Y., Chen, X., Wang, X., Zheng, K., Lian, D., & Chen, E. (2024). When large language models meet personalization: Perspectives of challenges and opportunities. World Wide Web, 27(4), 42. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, A., Chen, L.-K., Chang, Y.-C., Lee, S.-H., & Chang, J. S. (2023). Learning to paraphrase sentences to different complexity levels. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 11, 1332–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S., Xu, C., Xu, S., Pang, L., Dong, Z., & Xu, J. (2024, August 25–29). Bias and unfairness in information retrieval systems: New challenges in the llm era. 30th ACM Sigkdd Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 6437–6447), Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W. (2024). Recommender systems in the era of large language models (LLMs). IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 36(11), 6889–6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Y. (2015, September 17–21). Re-evaluating automatic summarization with BLEU and 192 shades of ROUGE. 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 128–137), Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, M. A., Barreiro, P. G., Crosetto, P., & Brockington, D. (2024). The strain on scientific publishing. Quantitative Science Studies, 5(4), 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Yu, W., Ma, W., Zhong, W., Feng, Z., Wang, H., Chen, Q., Peng, W., Feng, X., Qin, B., & Liu, T. (2025). A survey on hallucination in large language models: Principles, taxonomy, challenges, and open questions. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 43(2), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S. (2024). Should we publish fewer papers? ACS Energy Letters, 9(8), 4196–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M. R. (2023). A place for large language models in scientific publishing, apart from credited authorship. Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering, 16(2), 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoth, P., Herrmannova, D., Cancellieri, M., Anastasiou, L., Pontika, N., Pearce, S., Gyawali, B., & Pride, D. (2023). CORE: A global aggregation service for open access papers. Nature Scientific Data, 10(1), 366. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutz, C. K., & Schenkel, R. (2022). Scientific paper recommendation systems: A literature review of recent publications. arXiv, arXiv:2201.00682. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.00682 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Lubos, S., Tran, T. N. T., Felfernig, A., Polat Erdeniz, S., & Le, V.-M. (2024). LLM-generated explanations for recommender systems. In Adjunct Proceedings of the 32nd ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, Cagliari, Italy, July 1–4 (pp. 276–285). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvin, G., Hellen, N., Jjingo, D., & Nakatumba-Nabende, J. (2023, June 27–28). Prompt engineering in large language models. International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics (pp. 387–402), Tirunelveli, India. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V. K. (2024). Interdisciplinary trends in current research and development of science and technology. VNU Journal of Science: Policy and Management Studies, 40(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pranckutė, R. (2021). Web of Science (WoS) and scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications, 9(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X., Gao, M., & Wan, X. (2023). Summarization is (almost) dead. arXiv, arXiv:2309.09558. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.09558 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Publications, Volume 12, Issue 1. (2024). Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-6775/12/1 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Rosman, T., Mayer, A. K., & Krampen, G. (2016). On the pitfalls of bibliographic database searching: Comparing successful and less successful users. Behaviour & Information Technology, 35(2), 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, F. (2024). The scientific system must bend to avoid breaking. European Radiology, 34(9), 5866–5867. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shin, M., Soen, A., Readshaw, B. T., Blackburn, S. M., Whitelaw, M., & Xie, L. (2019, October 20–25). Influence flowers of academic entities. 2019 IEEE Conference on Visual Analytics Science and Technology (VAST) (pp. 1–10), Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G., Maria Colosimo, B., Martens, D., Padman, R., Saar-Tsechansky, M., R. Liu Sheng, O., Street, W. N., & Tsui, K.-L. (2023). How can IJDS authors, reviewers, and editors use (and misuse) generative AI? INFORMS Journal on Data Science, 2(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, A. Y., Kraft, A., Jin, L., Cai, C., Hosseini, A., Xu, T., Zhang, Z., Hong, L., Chi, E. H., & Yi, X. (2024). Leveraging llm reasoning enhances personalized recommender systems. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.00802 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Villalobos, P., Ho, A., Sevilla, J., Besiroglu, T., Heim, L., & Hobbhahn, M. (2022). Will we run out of data? Limits of LLM scaling based on human-generated data. arXiv, arXiv:2211.04325. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q., Li, J., Wang, S., Xing, Q., Niu, R., Kong, H., Li, R., Long, G., Chang, Y., & Zhang, C. (2024). Towards next-generation llm-based recommender systems: A survey and beyond. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.19744 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Wu, Y. (2024). Large Language Model and Text Generation. In H. Xu, & D. Demner Fushman (Eds.), Natural language processing in biomedicine: A practical guide (pp. 265–297). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakkas, P., Verberne, S., & Zavrel, J. (2024). SumBlogger: Abstractive summarization of large collections of scientific articles. In N. Goharian, N. Tonellotto, Y. He, A. Lipani, G. McDonald, C. Macdonald, & I. Ounis (Eds.), Advances in information retrieval (pp. 371–386). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., Patra, B. G., Yaseen, A., Zhu, J., Sabharwal, R., Roberts, K., Cao, T., & Wu, H. (2023). Scholarly recommendation systems: A literature survey. Knowledge and Information Systems, 65, 4433–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., Song, S., Duah, B., Macbeth, J., Carter, S., Van, M. P., Bravo, N. S., Klenk, M., Sick, K., & Filipowicz, A. L. (2023, June 19–21). More human than human: LLM-generated narratives outperform human-LLM interleaved narratives. 15th Conference on Creativity and Cognition (pp. 368–370), Virtual. [Google Scholar]

| The Title, Keywords, and Abstract of the Article with the Text in Bold for Persona A | The Title, Keywords, and Abstract of the Article with the Text in Bold for Persona B |

|---|---|

| Title: Bibliometric Overview of ChatGPT: New Perspectives in Social Sciences Keywords: ChatGPT; artificial intelligence; bibliometric analysis; ethical implications; educational technology; interdisciplinary research Abstract: This study delves into a bibliometric analysis of ChatGPT, an AI tool adept at analysing and generating text, highlighting its influence in the realm of social sciences. By harnessing data from the Scopus database, a total of 814 relevant publications were selected and scrutinised through VOSviewer, focusing on elements such as co-citations, keywords and international collaborations. The objective is to unearth prevailing trends and knowledge gaps in scholarly discourse regarding ChatGPT’s application in social sciences. Concentrating on articles from the year 2023, this analysis underscores the rapid evolution of this research domain, reflecting the ongoing digital transformation of society. This study presents a broad thematic picture of the analysed works, indicating a diversity of perspectives—from ethical and technological to sociological—regarding the implementation of ChatGPT in the fields of social sciences. This reveals an interest in various aspects of using ChatGPT, which may suggest a certain openness of the educational sector to adopting new technologies in the teaching process. These observations make a contribution to the field of social sciences, suggesting potential directions for future research, policy or practice, especially in less represented areas such as the socio-legal implications of AI, advocating for a multidisciplinary approach. | Title: Bibliometric Overview of ChatGPT: New Perspectives in Social Sciences Keywords: ChatGPT; artificial intelligence; bibliometric analysis; ethical implications; educational technology; interdisciplinary research Abstract: This study delves into a bibliometric analysis of ChatGPT, an AI tool adept at analysing and generating text, highlighting its influence in the realm of social sciences. By harnessing data from the Scopus database, a total of 814 relevant publications were selected and scrutinised through VOSviewer, focusing on elements such as co-citations, keywords and international collaborations. The objective is to unearth prevailing trends and knowledge gaps in scholarly discourse regarding ChatGPT’s application in social sciences. Concentrating on articles from the year 2023, this analysis underscores the rapid evolution of this research domain, reflecting the ongoing digital transformation of society. This study presents a broad thematic picture of the analysed works, indicating a diversity of perspectives—from ethical and technological to sociological—regarding the implementation of ChatGPT in the fields of social sciences. This reveals an interest in various aspects of using ChatGPT, which may suggest a certain openness of the educational sector to adopting new technologies in the teaching process. These observations make a contribution to the field of social sciences, suggesting potential directions for future research, policy or practice, especially in less represented areas such as the socio-legal implications of AI, advocating for a multidisciplinary approach. |

| Title: Benefits of Citizen Science for Libraries Keywords: benefits for libraries; citizen science; libraries; open science Abstract: Participating in collaborative scientific research through citizen science, a component of open science, holds significance for both citizen scientists and professional researchers. Yet, the advantages for those orchestrating citizen science initiatives are often overlooked. Organizers encompass a diverse range, including governmental entities, non-governmental organizations, corporations, universities, and institutions like libraries. For libraries, citizen science holds importance by fostering heightened civic and research interests, promoting scientific publishing, and contributing to overall scientific progress. This paper aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the specific ways in which citizen science can benefit libraries and how libraries can effectively utilize citizen science to achieve their goals. The paper is based on a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles that discuss the direct benefits of citizen science on libraries. A list of the main benefits of citizen science for libraries has been compiled from the literature. Additionally, the reasons why it is crucial for libraries to communicate the benefits of citizen science for their operations have been highlighted, particularly in terms of encouraging other libraries to actively engage in citizen science projects. | Title: Benefits of Citizen Science for Libraries Keywords: benefits for libraries; citizen science; libraries; open science Abstract: Participating in collaborative scientific research through citizen science, a component of open science, holds significance for both citizen scientists and professional researchers. Yet, the advantages for those orchestrating citizen science initiatives are often overlooked. Organizers encompass a diverse range, including governmental entities, non-governmental organizations, corporations, universities, and institutions like libraries. For libraries, citizen science holds importance by fostering heightened civic and research interests, promoting scientific publishing, and contributing to overall scientific progress. This paper aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the specific ways in which citizen science can benefit libraries and how libraries can effectively utilize citizen science to achieve their goals. The paper is based on a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles that discuss the direct benefits of citizen science on libraries. A list of the main benefits of citizen science for libraries has been compiled from the literature. Additionally, the reasons why it is crucial for libraries to communicate the benefits of citizen science for their operations have been highlighted, particularly in terms of encouraging other libraries to actively engage in citizen science projects. |

| Title: Should I Buy the Current Narrative about Predatory Journals? Facts and Insights from the Brazilian Scenario Keywords: predatory journals; scientometric; bias Abstract: The burgeoning landscape of scientific communication, marked by an explosive surge in published articles, journals, and specialized publishers, prompts a critical examination of prevailing assumptions. This article advocates a dispassionate and meticulous analysis to avoid policy decisions grounded in anecdotal evidence or superficial arguments. The discourse surrounding so-called predatory journals has been a focal point within the academic community, with concerns ranging from alleged lack of peer review rigor to exorbitant publication fees. While the consensus often leans towards avoiding such journals, this article challenges the prevailing narrative. It calls for a more nuanced understanding of what constitutes predatory practices and underscores the importance of skeptical inquiry within our daily academic activities. The authors aim to dispel misconceptions and foster a more informed dialogue by scrutinizing APCs, impact factors, and retractions. Furthermore, the authors delve into the evolving landscape of scientific publishing, addressing the generational shifts and emerging trends that challenge traditional notions of prestige and impact. In conclusion, this article serves as a call to action for the scientific community to engage in a comprehensive and nuanced debate on the complex issues surrounding scientific publishing. | Title: Should I Buy the Current Narrative about Predatory Journals? Facts and Insights from the Brazilian Scenario Keywords: predatory journals; scientometric; bias Abstract: The burgeoning landscape of scientific communication, marked by an explosive surge in published articles, journals, and specialized publishers, prompts a critical examination of prevailing assumptions. This article advocates a dispassionate and meticulous analysis to avoid policy decisions grounded in anecdotal evidence or superficial arguments. The discourse surrounding so-called predatory journals has been a focal point within the academic community, with concerns ranging from alleged lack of peer review rigor to exorbitant publication fees. While the consensus often leans towards avoiding such journals, this article challenges the prevailing narrative. It calls for a more nuanced understanding of what constitutes predatory practices and underscores the importance of skeptical inquiry within our daily academic activities. The authors aim to dispel misconceptions and foster a more informed dialogue by scrutinizing APCs, impact factors, and retractions. Furthermore, the authors delve into the evolving landscape of scientific publishing, addressing the generational shifts and emerging trends that challenge traditional notions of prestige and impact. In conclusion, this article serves as a call to action for the scientific community to engage in a comprehensive and nuanced debate on the complex issues surrounding scientific publishing. |

| Title: FAIRness of Research Data in the European Humanities Landscape Keywords: datasets; humanities; FAIR; repositories; openness; licencing; research data Abstract: This paper explores the landscape of research data in the humanities in the European context, delving into their diversity and the challenges of defining and sharing them. It investigates three aspects: the types of data in the humanities, their representation in repositories, and their alignment with the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable). By reviewing datasets in repositories, this research determines the dominant data types, their openness, licensing, and compliance with the FAIR principles. This research provides important insight into the heterogeneous nature of humanities data, their representation in the repository, and their alignment with FAIR principles, highlighting the need for improved accessibility and reusability to improve the overall quality and utility of humanities research data. | Title: FAIRness of Research Data in the European Humanities Landscape Keywords: datasets; humanities; FAIR; repositories; openness; licencing; research data Abstract: This paper explores the landscape of research data in the humanities in the European context, delving into their diversity and the challenges of defining and sharing them. It investigates three aspects: the types of data in the humanities, their representation in repositories, and their alignment with the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable). By reviewing datasets in repositories, this research determines the dominant data types, their openness, licensing, and compliance with the FAIR principles. This research provides important insight into the heterogeneous nature of humanities data, their representation in the repository, and their alignment with FAIR principles, highlighting the need for improved accessibility and reusability to improve the overall quality and utility of humanities research data. |

| Title: Reducing the Matthew Effect on Journal Citations through an Inclusive Indexing Logic: The Brazilian Spell (Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library) Experience Keywords: indexers; impact factor; inequality; Matthew effect; citations; journals Abstract: The inclusion of scientific journals in prestigious indexers is often associated with higher citation rates; journals included in such indexers are significantly more acknowledged than those that are not included in them. This phenomenon refers to the Matthew effect on journal citations, according to which journals in exclusive rankings tend to be increasingly cited. This paper shows the opposite: that the inclusion of journals in local indexers ruled by inclusive logic reduces the Matthew effect on journal citations since it enables them to be equally exposed. Thus, we based our arguments on the comparison of 68 Brazilian journals before and after they were indexed in the Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library (Spell), which ranks journals in the Brazilian management field based on local citations. Citation impact indicators and iGini (a new individual inequality analysis measure) were used to show that the inclusion of journals in Spell has probably increased their impact factor and decreased their citation inequality rates. Using a difference-in-differences model with continuous treatment, the results indicated that the effect between ranking and inequality declined after journals were included in Spell. Additional robustness checks through event study models and interrupted time-series analysis for panel data point to a reduction in citation inequality but follow different trajectories for the 2- and 5-year impact. The results indicate that the indexer has reduced the Matthew effect on journal citations. | Title: Reducing the Matthew Effect on Journal Citations through an Inclusive Indexing Logic: The Brazilian Spell (Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library) Experience Keywords: indexers; impact factor; inequality; Matthew effect; citations; journals Abstract: The inclusion of scientific journals in prestigious indexers is often associated with higher citation rates; journals included in such indexers are significantly more acknowledged than those that are not included in them. This phenomenon refers to the Matthew effect on journal citations, according to which journals in exclusive rankings tend to be increasingly cited. This paper shows the opposite: that the inclusion of journals in local indexers ruled by inclusive logic reduces the Matthew effect on journal citations since it enables them to be equally exposed. Thus, we based our arguments on the comparison of 68 Brazilian journals before and after they were indexed in the Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library (Spell), which ranks journals in the Brazilian management field based on local citations. Citation impact indicators and iGini (a new individual inequality analysis measure) were used to show that the inclusion of journals in Spell has probably increased their impact factor and decreased their citation inequality rates. Using a difference-in-differences model with continuous treatment, the results indicated that the effect between ranking and inequality declined after journals were included in Spell. Additional robustness checks through event study models and interrupted time-series analysis for panel data point to a reduction in citation inequality but follow different trajectories for the 2- and 5-year impact. The results indicate that the indexer has reduced the Matthew effect on journal citations. |

| The Title, Keywords, and Abstract of the Article with the Text in Bold for Persona A | The Title, Keywords, and Abstract of the Article with the Text in Bold for Persona B |

|---|---|

| Title: Does Quality Matter? Quality Assurance in Research for the Chilean Higher Education System Keywords: scientific research; universities; quality assurance; scientometric indicators; Chile Abstract: This study analyzes the research quality assurance processes in Chilean universities. Data from 29 universities accredited by the National Accreditation Commission were collected. The relationship between institutional accreditation and research performance was analyzed using length in years of institutional accreditation and eight research metrics used as the indicators of quantity, quality, and impact of a university’s outputs at an international level. The results showed that quality assurance in research of Chilean universities is mainly associated with quantity and not with the quality and impact of academic publications. There was also no relationship between the number of publications and their quality, even finding cases with negative correlations. In addition to the above, the relationship between international metrics to evaluate research performance (i.e., international collaboration, field-weighted citation impact, and output in the top 10% citation percentiles) showed the existence of three clusters of heterogeneous composition regarding the distribution of universities with different years of institutional accreditation. These findings call for a new focus on improving regulatory processes to evaluate research performance and adequately promote institutions’ development and the effectiveness of their mission. | Title: Does Quality Matter? Quality Assurance in Research for the Chilean Higher Education System Keywords: scientific research; universities; quality assurance; scientometric indicators; Chile Abstract: This study analyzes the research quality assurance processes in Chilean universities. Data from 29 universities accredited by the National Accreditation Commission were collected. The relationship between institutional accreditation and research performance was analyzed using length in years of institutional accreditation and eight research metrics used as the indicators of quantity, quality, and impact of a university’s outputs at an international level. The results showed that quality assurance in research of Chilean universities is mainly associated with quantity and not with the quality and impact of academic publications. There was also no relationship between the number of publications and their quality, even finding cases with negative correlations. In addition to the above, the relationship between international metrics to evaluate research performance (i.e., international collaboration, field-weighted citation impact, and output in the top 10% citation percentiles) showed the existence of three clusters of heterogeneous composition regarding the distribution of universities with different years of institutional accreditation. These findings call for a new focus on improving regulatory processes to evaluate research performance and adequately promote institutions’ development and the effectiveness of their mission. |

| Title: Mining and Mineral Processing Journals in the WoS and Their Rankings When Merging SCIEx and ESCI Databases—Case Study Based on the JCR 2022 Data Keywords: Mining and Mineral Processing journals; WoS; SCIEx; ESCI; ranking Abstract: The 2022 JCR included ESCI journals for the first time, increasing the number of publication titles by approximately 60%. In this paper, the subcategory Mining and Mineral Processing (part of the Engineering and Geosciences category, where 12 of the ESCI journals were merged with the 20 SCIEx ones) is presented and analyzed. Only three of the ESCI journals included in the database were ranked Q1/Q2. The inclusion of the entire ESCI added new content for readers and authors relying on JCR sources. This paper offers authors, researchers, and publishers in the Mining and Mineral Processing field practical insights into the potential benefits and challenges associated with the changing landscape of indexed journals, as well as in-depth, systematic analyses that provide potential authors with the opportunity to select the most suitable journal for submitting their papers. | Title: Mining and Mineral Processing Journals in the WoS and Their Rankings When Merging SCIEx and ESCI Databases—Case Study Based on the JCR 2022 Data Keywords: Mining and Mineral Processing journals; WoS; SCIEx; ESCI; ranking Abstract: The 2022 JCR included ESCI journals for the first time, increasing the number of publication titles by approximately 60%. In this paper, the subcategory Mining and Mineral Processing (part of the Engineering and Geosciences category, where 12 of the ESCI journals were merged with the 20 SCIEx ones) is presented and analyzed. Only three of the ESCI journals included in the database were ranked Q1/Q2. The inclusion of the entire ESCI added new content for readers and authors relying on JCR sources. This paper offers authors, researchers, and publishers in the Mining and Mineral Processing field practical insights into the potential benefits and challenges associated with the changing landscape of indexed journals, as well as in-depth, systematic analyses that provide potential authors with the opportunity to select the most suitable journal for submitting their papers. |

| Title: Tracing the Evolution of Reviews and Research Articles in the Biomedical Literature: A Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Abstracts Keywords: abstract; narrativity; scientific publishing Abstract:We previously examined the diachronic shifts in the narrative structure of research articles (RAs) and review manuscripts using abstract corpora from MEDLINE. This study employs Nini’s Multidimensional Analysis Tagger (MAT) on the same datasets to explore five linguistic dimensions (D1–5) in these two sub-genres of biomedical literature, offering insights into evolving writing practices over 30 years. Analyzing a sample exceeding 1.2 million abstracts, we observe a shared reinforcement of an informational, emotionally detached tone (D1) in both RAs and reviews. Additionally, there is a gradual departure from narrative devices (D2), coupled with an increase in context-independent content (D3). Both RAs and reviews maintain low levels of overt persuasion (D4) while shifting focus from abstract content to emphasize author agency and identity. A comparison of linguistic features underlying these dimensions reveals often independent changes in RAs and reviews, with both tending to converge toward standardized stylistic norms. | Title: Tracing the Evolution of Reviews and Research Articles in the Biomedical Literature: A Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Abstracts Keywords: abstract; narrativity; scientific publishing Abstract:We previously examined the diachronic shifts in the narrative structure of research articles (RAs) and review manuscripts using abstract corpora from MEDLINE. This study employs Nini’s Multidimensional Analysis Tagger (MAT) on the same datasets to explore five linguistic dimensions (D1–5) in these two sub-genres of biomedical literature, offering insights into evolving writing practices over 30 years. Analyzing a sample exceeding 1.2 million abstracts, we observe a shared reinforcement of an informational, emotionally detached tone (D1) in both RAs and reviews. Additionally, there is a gradual departure from narrative devices (D2), coupled with an increase in context-independent content (D3). Both RAs and reviews maintain low levels of overt persuasion (D4) while shifting focus from abstract content to emphasize author agency and identity. A comparison of linguistic features underlying these dimensions reveals often independent changes in RAs and reviews, with both tending to converge toward standardized stylistic norms. |

| Title: Going Open Access: The Attitudes and Actions of Scientific Journal Editors in China Keywords: open access; scientific journals; editors; China Abstract: This study aims to investigate the attitudes and actions of scientific journal editors in China towards open access. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 17 Chinese editors from various scientific journals during September and October of 2022. The results indicate that the editors generally possess knowledge of open access and have implemented an appropriate open access model for their respective journals. However, the Chinese-language journal editors expressed a lack of motivation to adopt open access, unless there is a reform in the mechanism of academic publishing or a policy is imposed. On the other hand, the English-language journal editors acknowledged that they have no other choice but to adopt open access. This study helps us learn about Chinese editors’ understanding and attitudes towards open access, the current status of open access in China’s scientific journals, and the mechanisms of academic publishing in China. | Title: Going Open Access: The Attitudes and Actions of Scientific Journal Editors in China Keywords: open access; scientific journals; editors; China Abstract: This study aims to investigate the attitudes and actions of scientific journal editors in China towards open access. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 17 Chinese editors from various scientific journals during September and October of 2022. The results indicate that the editors generally possess knowledge of open access and have implemented an appropriate open access model for their respective journals. However, the Chinese-language journal editors expressed a lack of motivation to adopt open access, unless there is a reform in the mechanism of academic publishing or a policy is imposed. On the other hand, the English-language journal editors acknowledged that they have no other choice but to adopt open access. This study helps us learn about Chinese editors’ understanding and attitudes towards open access, the current status of open access in China’s scientific journals, and the mechanisms of academic publishing in China. |

| The Title of Paper | Persona A | Persona B |

|---|---|---|

| Bibliometric Overview of ChatGPT: New Perspectives in Social Sciences | Rating: 5 (Extremely interested) Justification: The article’s focus on ChatGPT’s impact on social sciences and its bibliometric analysis directly aligns with her interests in AI, bibliometrics, and the digital transformation of research. | Rating: 2 (Slightly interested) Justification: Although the bibliometric approach might catch his eye, the focus on social sciences and ChatGPT isn’t closely aligned with his technical and mining industry priorities. |

| Benefits of Citizen Science for Libraries | Rating: 4 (Very interested) Justification: Exploring how citizen science enhances library services and fosters open research practices resonates with her commitment to open science and collaborative research in the humanities. | Rating: 1 (Not at all interested) Justification: The topic centers on libraries and citizen science, which is largely irrelevant to his work in mining and technical research trends. |

| Should I Buy the Current Narrative about Predatory Journals? Facts and Insights from the Brazilian Scenario | Rating: 4 (Very interested) Justification: The critical examination of predatory journals, impact factors, and publishing ethics is highly relevant given her focus on open science, ethical publishing, and bibliometric methods. | Rating: 3 (Moderately interested) Justification: The discussion on publication practices and metrics may offer some insight into broader scientific publishing trends, though it is not directly tied to the technical focus of his industry. |

| FAIRness of Research Data in the European Humanities Landscape | Rating: 5 (Extremely interested) Justification: With its emphasis on FAIR principles and challenges in data sharing in the humanities, this paper directly supports her research into data accessibility and open science within digital humanities. | Rating: 1 (Not at all interested) Justification: The emphasis on humanities research data and FAIR principles is outside his core technical and industrial focus. |

| Reducing the Matthew Effect on Journal Citations through an Inclusive Indexing Logic: The Brazilian Spell (Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library) Experience | Rating: 4 (Very interested) Justification: The discussion on citation dynamics and inclusive indexing connects with her interests in bibliometrics and the evaluation of scholarly communication, despite its regional case study. | Rating: 4 (Very interested) Justification: The insights into citation dynamics and journal indexing are highly relevant to his interest in understanding how scientific publishing trends affect industry recognition and technical research visibility. |

| Does Quality Matter? Quality Assurance in Research for the Chilean Higher Education System | Rating: 3 (Moderately interested) Justification: Although the focus on quality assurance and research metrics is relevant, the Chilean higher education context makes it slightly less central to her main areas of digital humanities and open science. | Rating: 2 (Slightly interested) Justification: While research quality assurance touches on broader academic performance metrics, its focus on Chilean universities is not directly relevant to his field in mining and raw materials. |

| Mining and Mineral Processing Journals in the WoS and Their Rankings When Merging SCIEx and ESCI Databases—Case Study Based on the JCR 2022 Data | Rating: 1 (Not at all interested) Justification: This article’s focus on mining and mineral processing is far removed from her expertise and interests in the humanities and open science. | Rating: 5 (Extremely interested) Justification: This paper is directly aligned with his area of expertise, offering valuable insights into the indexing and ranking of journals specifically related to mining and mineral processing. |

| Tracing the Evolution of Reviews and Research Articles in the Biomedical Literature: A Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Abstracts | Rating: 3 (Moderately interested) Justification: While the methodological approach and analysis of scholarly communication might be of interest, its biomedical focus makes it less directly applicable to her research focus. | Rating: 1 (Not at all interested) Justification: The focus on biomedical literature and linguistic analysis does not intersect with his primary interests in the technical and industrial aspects of mining. |

| Going Open Access: The Attitudes and Actions of Scientific Journal Editors in China | Rating: 5 (Extremely interested) Justification: The exploration of open access practices and the attitudes of journal editors is highly pertinent to her core interests in open science and the evolving landscape of academic publishing. | Rating: 3 (Moderately interested) Justification: Although the focus on open access models and editorial attitudes offers some insight into publishing trends, its specific context (Chinese journals) makes it only moderately relevant to his technical and industry-focused interests. |

| The Title of Paper | Persona A | Persona B |

|---|---|---|

| Bibliometric Overview of ChatGPT: New Perspectives in Social Sciences |

|

|

| Benefits of Citizen Science for Libraries |

|

|

| Should I Buy the Current Narrative about Predatory Journals? Facts and Insights from the Brazilian Scenario |

|

|

| FAIRness of Research Data in the European Humanities Landscape |

|

|

| Reducing the Matthew Effect on Journal Citations through an Inclusive Indexing Logic: The Brazilian Spell (Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library) Experience |

|

|

| The Title of Paper | Persona A | Persona B |

|---|---|---|

| Does Quality Matter? Quality Assurance in Research for the Chilean Higher Education System |

|

|

| Mining and Mineral Processing Journals in the WoS and Their Rankings When Merging SCIEx and ESCI Databases—Case Study Based on the JCR 2022 Data |

|

|

| Tracing the Evolution of Reviews and Research Articles in the Biomedical Literature: A Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Abstracts |

|

|

| Going Open Access: The Attitudes and Actions of Scientific Journal Editors in China |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamińska, A.M. Tailoring Scientific Knowledge: How Generative AI Personalizes Academic Reading Experiences. Publications 2025, 13, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications13020018

Kamińska AM. Tailoring Scientific Knowledge: How Generative AI Personalizes Academic Reading Experiences. Publications. 2025; 13(2):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications13020018

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamińska, Anna Małgorzata. 2025. "Tailoring Scientific Knowledge: How Generative AI Personalizes Academic Reading Experiences" Publications 13, no. 2: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications13020018

APA StyleKamińska, A. M. (2025). Tailoring Scientific Knowledge: How Generative AI Personalizes Academic Reading Experiences. Publications, 13(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications13020018