Identifying Risk Factors Affecting the Usage of Digital and Social Media: A Preliminary Qualitative Study in the Dental Profession and Dental Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and the Setting

2.2. Interview Procedure

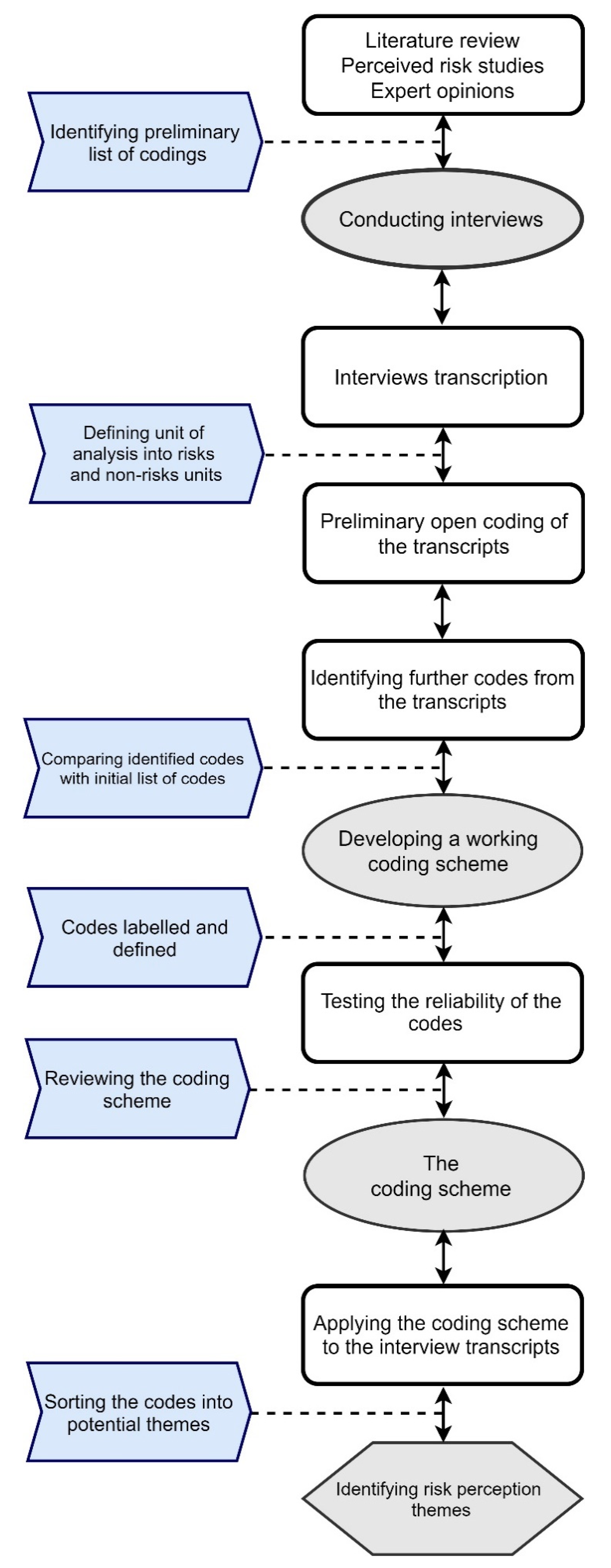

2.3. Thematic Analysis Process and Coding

3. Results

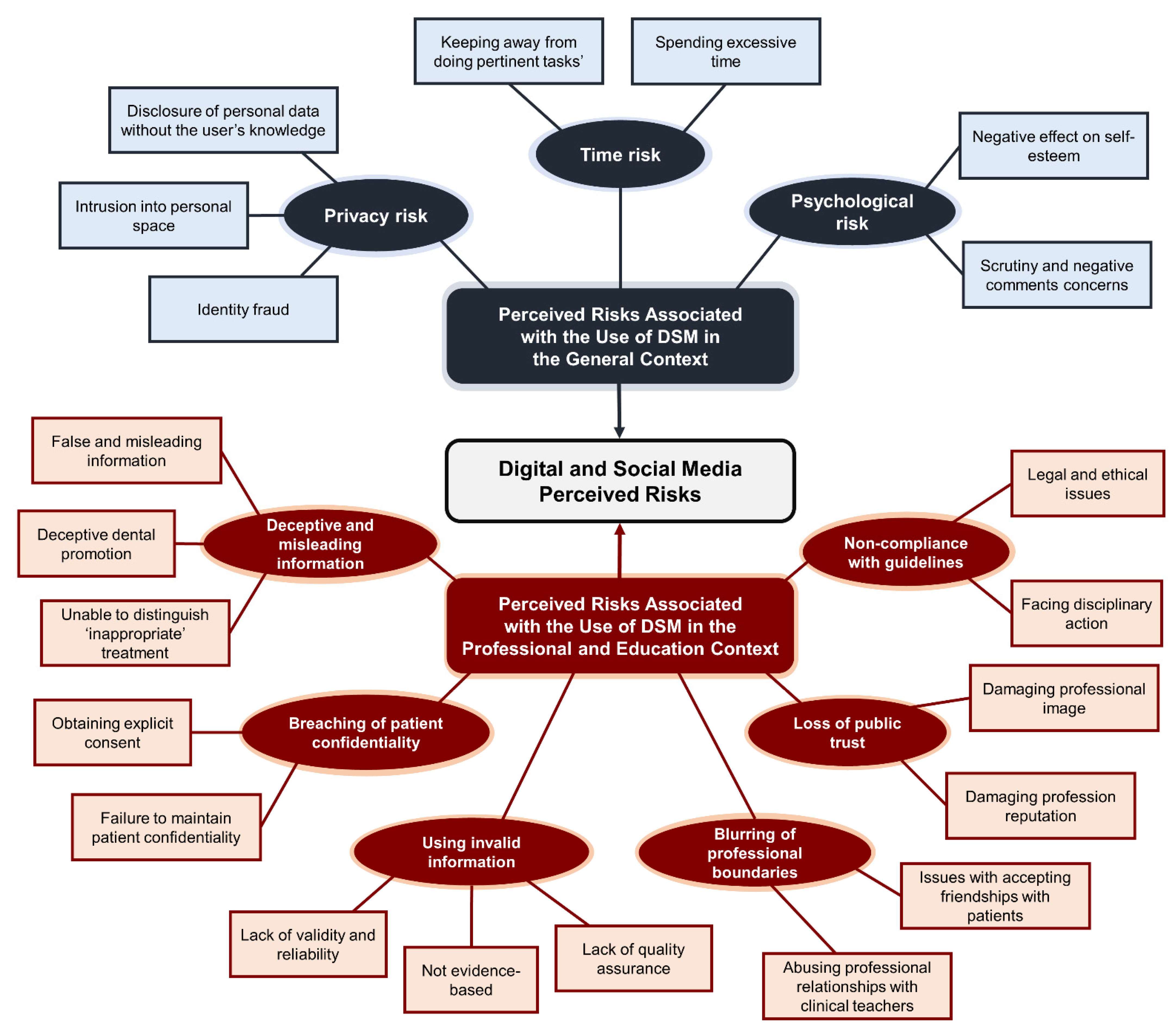

3.1. Perceived Risk Themes Associated with the Use of DSM in the General Context

3.1.1. Theme (1): Privacy Risk

3.1.2. Theme (2): Psychological Risk

3.1.3. Theme (3): Time Risk

3.2. Perceived Risk Themes Associated with the Use of DSM in the Professional and Education Context

3.2.1. Theme (4): Using Invalid Information

3.2.2. Theme (5): Non-Compliance with Guidelines

3.2.3. Theme (6): Breaches of Patients’ Confidentiality

3.2.4. Theme (7): Deceptive and Misleading Information

3.2.5. Theme (8): Blurring of Professional Boundaries

3.2.6. Theme (9): Loss of Public Trust

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital in 2020: Global Internet Use Accelerates. 2020. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/digital-2020 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Dobson, E.; Patel, P.; Neville, P. Perceptions of e-professionalism among dental students: A UK dental school study. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, M.R.; Loewen, J.M.; Romito, L.M. Use of social media by dental educators. J. Dent. Educ. 2013, 77, 1402–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S.; Gadbury-Amyot, C. Using Twitter for Teaching and Learning in an Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology Course. J. Dent. Educ. 2016, 80, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, S.; Duane, B. Delivery of information to orthodontic patients using social media. Evid. Based Dent. 2017, 18, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, N.; Dong, L.; Eisingerich, A.B. Connecting with Your Dentist on Facebook: Patients’ and Dentists’ Attitudes Towards Social Media Usage in Dentistry. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhola, S.; Hellyer, P. The risks and benefits of social media in dental foundation training. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 221, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, A.C.; Stokes, C.W.; Zijlstra-Shaw, S.; Sandars, J.E. Conflicting demands that dentists and dental care professionals experience when using social media: A scoping review. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, M.S.; Pavlou, P.A. Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. Int. J. Hum. Comput. 2003, 59, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.F.; Swar, B.; Lee, S.K. Social Media Risks and Benefits: A Public Sector Perspective. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2014, 32, 606–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, A.C.L. Paradise Lost; the reputation of the dental profession and regulatory scope. Br. Dent. J. 2017, 222, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Peralta, T.L.; Farrior, O.F.; Flake, N.M.; Gallagher, D.; Susin, C.; Valenza, J. The Use of Social Media by Dental Students for Communication and Learning: Two Viewpoints. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 83, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, P.; Johnson, I.G. Social media use, attitudes, behaviours and perceptions of online professionalism amongst dental students. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 221, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, M.R.; Christensen, H.L.; Nelson, B.A. A school-wide assessment of social media usage by students in a US dental school. Br. Dent. J. 2014, 217, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennardo, F.; Buffone, C.; Fortunato, L.; Giudice, A. COVID-19 is a challenge for dental education—A commentary. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 24, 822–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Nicholls, C.M.; Ormston, R. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2003; pp. 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 418–419. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Majid, M.; Othman, M.; Mohamad, S.; Lim, S.A.H.; Yusof, A. Piloting for Interviews in Qualitative Research: Operationalization and Lessons Learnt. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar]

- DeCuir-Gunby, J.T.; Marshall, P.L.; McCulloch, A.W. Developing and using a codebook for the analysis of interview data: An example from a professional development research project. Field Methods 2011, 23, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, C.; Khoza, N.; Abler, L.; Ranganathan, M. Process guidelines for establishing intercoder reliability in qualitative studies. Qual. Res. 2016, 16, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Chen, P.L.; Kuo, Y.C. Understanding the facilitators and inhibitors of individuals’ social network site usage. Online Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, D.; Chun, H. The Emotional Impact of Social Media in Higher Education. Int. J. High Educ. 2020, 9, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, J.; Hershenberg, R.; Feinstein, B.A.; Gorman, K.; Bhatia, V.; Starr, L.R. Frequency and Quality of Social Networking Among Young Adults: Associations with Depressive Symptoms, Rumination, and Corumination. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2012, 1, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajeh, M.; Sembawa, S.; Nassar, A.; Al Hebshi, S.A.; Aboalshamat, K.T.; Badri, M.K. Social media as a learning tool: Dental students’ perspectives. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, B.; Hill, K.; Walmsley, A.D. Mobile learning in dentistry: Challenges and opportunities. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharka, R.; Abed, H.; Dziedzic, A. Can Undergraduate Dental Education be Online and Virtual During the COVID-19 Era? Clinical Training as a Crucial Element of Practical Competencies. Med. Ed. Publish. 2020, 30, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Dental Council. Guidance on Using Social Media. 2016. Available online: https://www.gdcuk.org/api/files/Guidance%20on%20using%20social%20media.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Tatullo, M. Science is not a Social Opinion. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.; Kelleher, M. The Dangers of Social Media and Young Dental Patients’ Body Image. Dent. Update 2018, 45, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuttleworth, J.; Smith, W. NHS dentistry: The social media challenge. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 220, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Codes | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| The possibility of an adverse effect on the users’ peace of mind or self-esteem from using DSM. | “I believe that DSM does affect self-esteem due to exposing users to a vast number of photos, such as ideal body image, that would affect self-esteem or self-image”. |

| The possibility of receiving negative comments and criticism from using DSM. | “I will receive negative remarks from others if I use DSM”. |

| The potential loss of control over personal information leads to the information being used without the user’s knowledge or permission. | “Someone else can take the photo that I posted on my profile and use it without my consent”. |

| The state when personal/private life is observed or disturbed by others. | “Using DSM would allow others to observe my private life”. |

| The potential loss of control over the DSM profile and account due to hacking and criminal attacks. | “Internet hackers (criminals) might take control of my checking account if I used a DSM”. |

| The possibility of losing time when using DSM by wasting time searching and browsing different activities on DSM. | “There is a possible time loss due to engaging in different activities on DSM”. |

| The possibility of losing the time for doing important tasks (e.g., studying, exercising, etc.) | “If I had begun to use DSM, there are chances that I will lose time doing other essential tasks”. |

| The potential loss of status in one’s social group due to adopting DSM. | “My signing up for and using DSM would lead to a social loss for me because my friends and relatives would think less highly of me”. |

| The potential loss of money due to adopting DSM. | “There are the chances that you stand to lose money if you use DSM”. |

| The possibility of the DSM not performing as it was designed and advertised. | “DSM might not perform well and create problems”. |

| The possibility of using/sharing unreliable and invalid information on DSM. | “The information posted on DSM is poorly referenced and unreliable”. |

| The possibility of using/sharing not evidence-based information on DSM. | “On YouTube and Google, you have to be careful in terms of what you are taking as evidence-based or not”. |

| The possibility that the information shared on DSM is not critically appraised to ensure its quality. | “The information posted on DSM has a lack of quality assurance.” |

| The possibility of facing disciplinary action from using DSM. | “You must be aware and not make a mistake when using DSM to avoid disciplinary action”. |

| The possibility of exposure to legal penalties from using DSM. | “There is a risk of legal and ethical issues associated with DSM usage”. |

| The state of damage the professional image when using DSM inappropriately. | “I think using DSM is risky because anything you put could stay forever and affect your professional image”. |

| The possibility of violating guidelines when using DSM. | “It is crucial to make sure that all the regulations are followed when using DSM”. |

| The possibility of violating and breaching patients’ confidentiality when using DSM. | “I believe that using DSM is good as long as they do not expose patient privacy”. |

| The possibility of sharing patients’ information on DSM without explicit consent. | “There is a risk of sharing patients’ photos on DSM without explicit consent”. |

| The state of sharing misleading information when using DSM. | “There is lots of misleading and false information shared on DSM”. |

| The state of sharing deceptive dental promotions on DSM. | “Someone can easily photoshop and play with the quality of clinical work and enhance how the treatment looks”. |

| Perceived Risk Themes Associated with the Use of DSM in the General Context | Number of Participants | Number of Occurrences |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | 25 |

| 14 | 18 |

| 11 | 13 |

| Perceived Risk Themes Associated with the Use of DSM in the Professional and Education Context | Number of Participants | Number of Occurrences |

| 14 | 20 |

| 10 | 17 |

| 10 | 15 |

| 9 | 12 |

| 8 | 10 |

| 7 | 10 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharka, R.; San Diego, J.P.; Nasseripour, M.; Banerjee, A. Identifying Risk Factors Affecting the Usage of Digital and Social Media: A Preliminary Qualitative Study in the Dental Profession and Dental Education. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9050053

Sharka R, San Diego JP, Nasseripour M, Banerjee A. Identifying Risk Factors Affecting the Usage of Digital and Social Media: A Preliminary Qualitative Study in the Dental Profession and Dental Education. Dentistry Journal. 2021; 9(5):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9050053

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharka, Rayan, Jonathan P. San Diego, Melanie Nasseripour, and Avijit Banerjee. 2021. "Identifying Risk Factors Affecting the Usage of Digital and Social Media: A Preliminary Qualitative Study in the Dental Profession and Dental Education" Dentistry Journal 9, no. 5: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9050053

APA StyleSharka, R., San Diego, J. P., Nasseripour, M., & Banerjee, A. (2021). Identifying Risk Factors Affecting the Usage of Digital and Social Media: A Preliminary Qualitative Study in the Dental Profession and Dental Education. Dentistry Journal, 9(5), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9050053