Treatment of Dental Anxiety and Phobia—Diagnostic Criteria and Conceptual Model of Behavioural Treatment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method

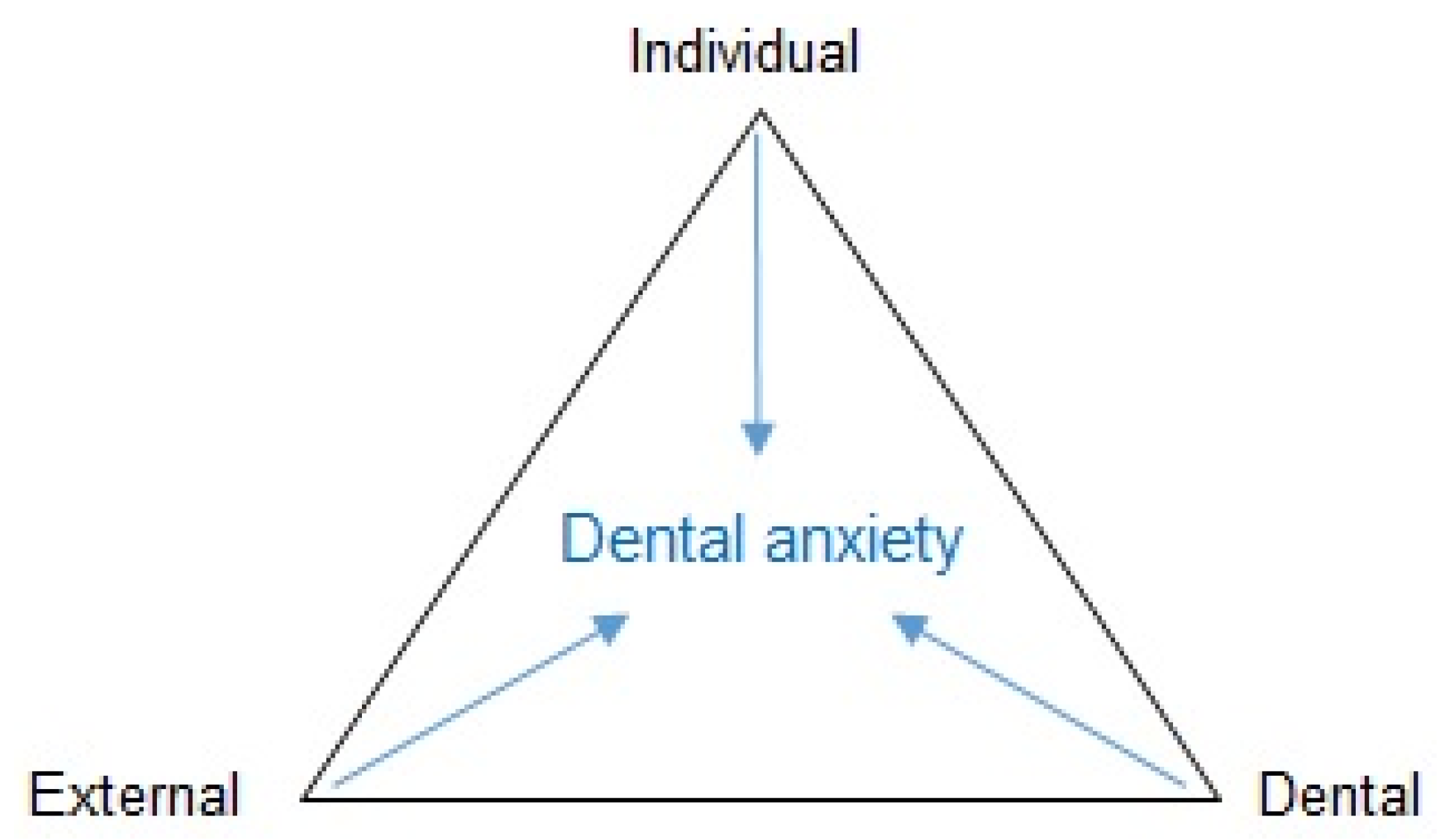

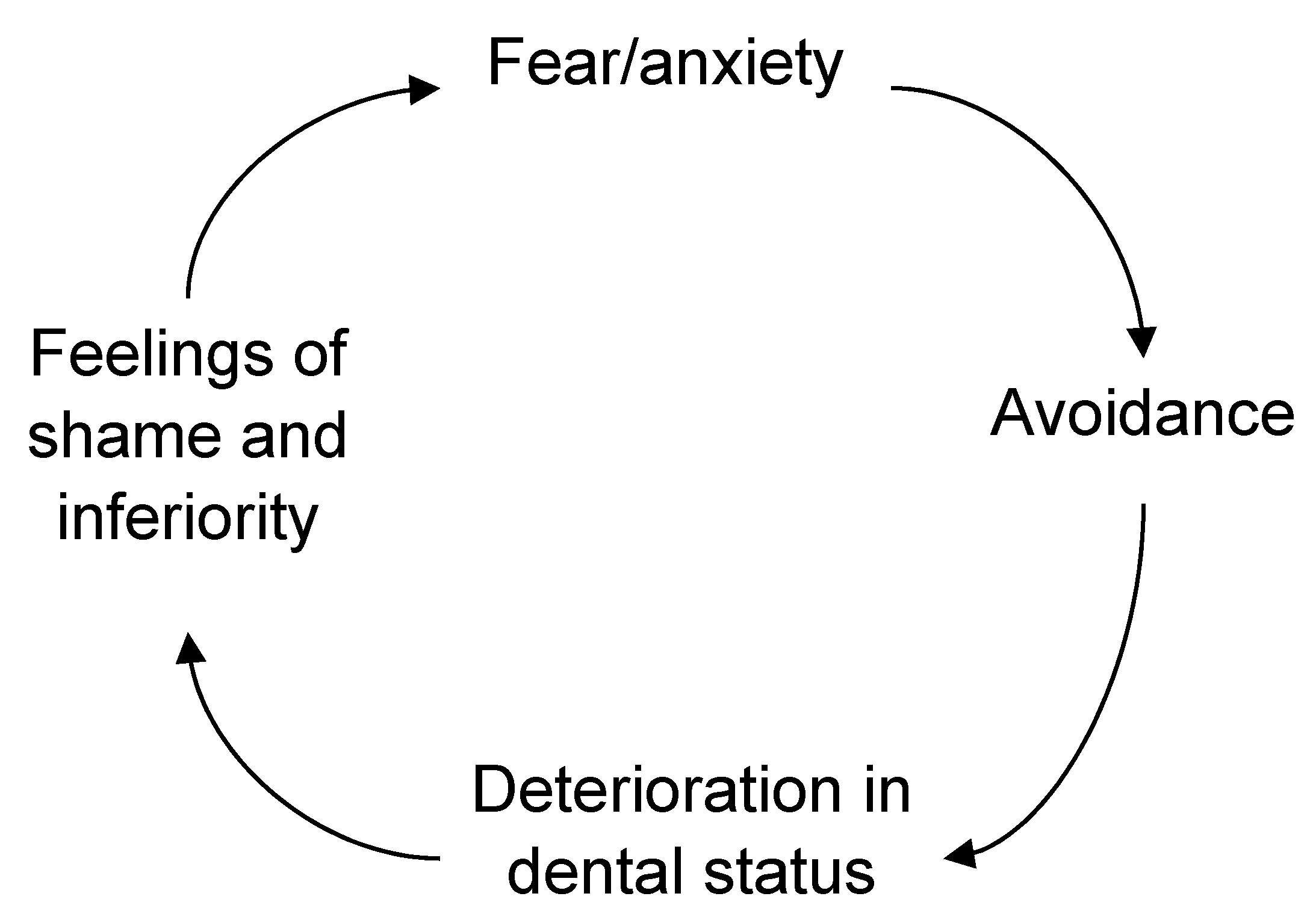

3. Dental Anxiety, Aetiology and Dental Public Health

4. Dental Anxiety and Prevalence

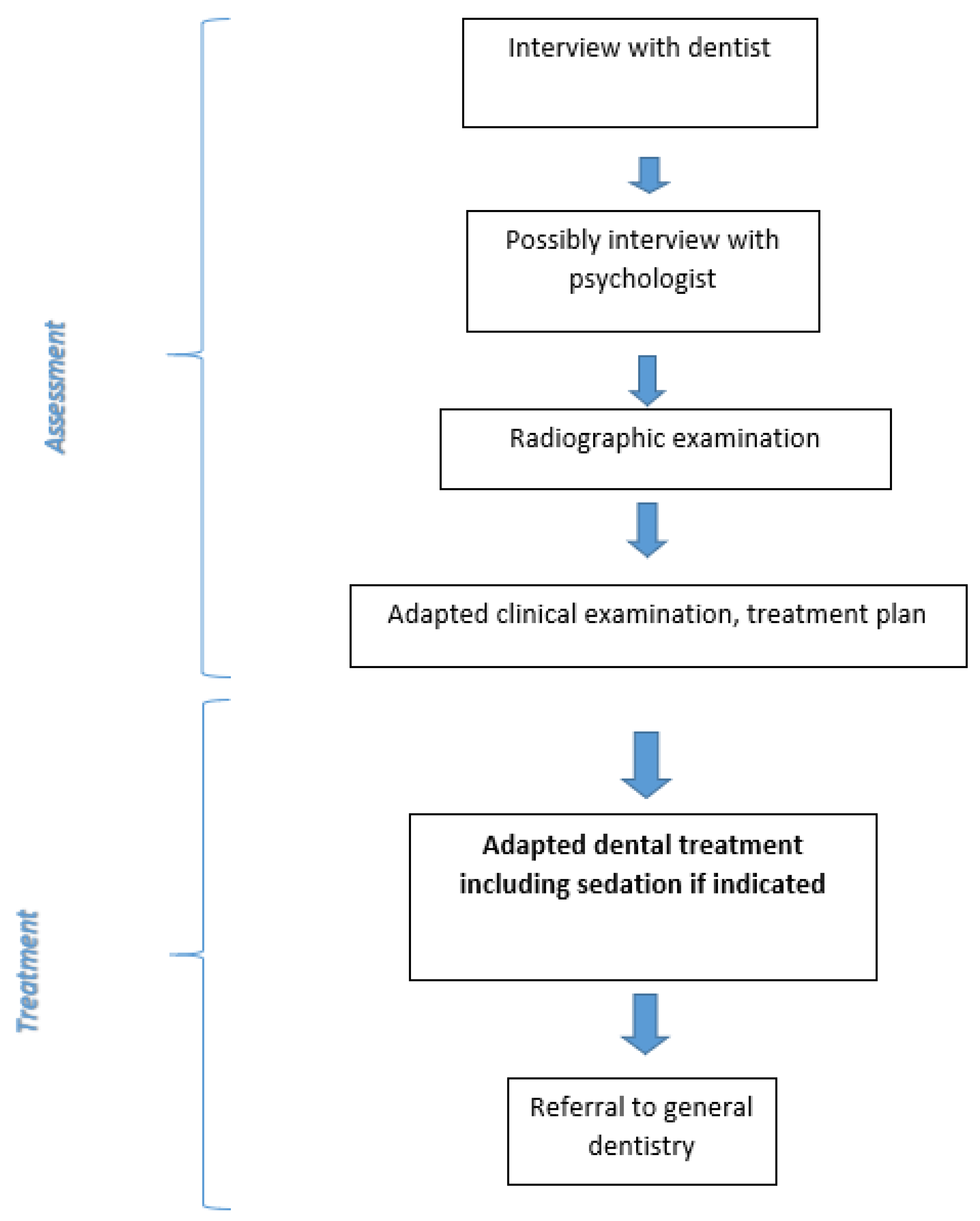

5. Setting a Diagnosis of Dental Anxiety/Phobia

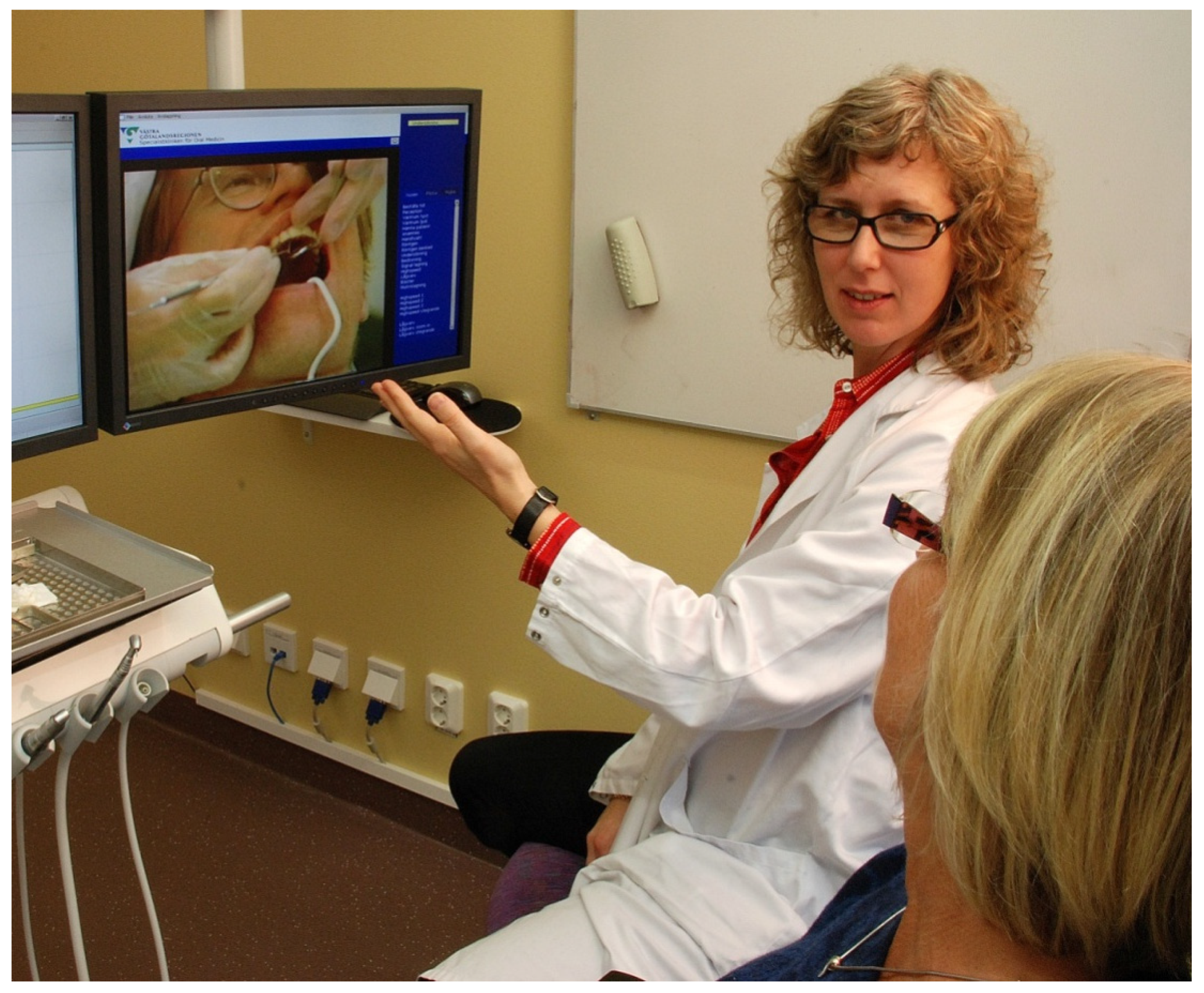

6. Conceptual Treatment Model

7. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carlsson, S.G.; Wide Boman, U.; Lundgren, J.; Hakeberg, M. Dental anxiety—A joint interest for dentists and psychologists. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2013, 121, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, U. Dental Fear and Avoidance. A Study of Etiology, Consequences and Treatment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hakeberg, M. Dental Anxiety and Health. A Prevalence Study and Assessment of Treatment Outcomes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, K.J. Epidemiology, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Klingberg, G.; Raadal, M.; Anrup, K. Dental fear and behaviour management problems. In Pediatric Dentistry: A Clinical Approach, 2nd ed.; Koch, G., Poulsen, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wide, S.; Wide Boman, U. Explanation and causal reasoning: A contribution to the interpretation of competing explanatory claims. Theory Psychol. 2013, 23, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jongh, A.; Schutjes, M.; Aartman, I.H. A test of Berggren’s model of dental fear and anxiety. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 119, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DMS-5), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, L. Dental Anxiety. Prevalence, Measurements, and Consequences. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th ed.; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, L.; Hakeberg, M.; Wide Boman, U. Dental anxiety, concomitant factors and change in prevalence over 50 years. Community Dent. Health 2016, 33, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Stenebrand, A.; Hakeberg, H.; Helkemo, A.N.; Koch, G.; Wide Boman, U. Dental anxiety and oral health in 15-year-olds: A repeated crossectional study over 30 years. Community Dent. Health 2015, 32, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Åström, A.N.; Skaret, E.; Haugejorden, O. Dental anxiety and dental attendance among 25-year-olds in Norway: Time trends from 1997 to 2007. BMC Oral Health 2011, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ström, K.; Skaare, A.B.; Willumsen, T.D. Dental anxiety in 18-year-old Norwegians in 1996 and 2016. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2020, 78, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wide Boman, U.; Wennström, A.; Stenman, U.; Hakeberg, M. Oral health-related quality of life, sense of coherence and dental anxiety: An epidemiological crossectional study of middle-aged women. BMC Oral Health 2012, 12, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, V.; Hakeberg, M.; Wide Boman, U. Associations between dental anxiety, sense of coherence, oral health-related quality of life and health behaviour—A national Swedish crossectionl survey. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pohjola, V.; Lahti, S.; Souminen-Taipale, L.; Hausen, H. Dental fear and subjective oral impacts among adults in Finland. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2009, 117, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrstedt, M.; John, M.T.; Tönnies, S.; Micheelis, W. Oral health-related quality of life in patients with dental anxiety. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakeberg, M.; Lundgren, J. Symptoms, clinical characteristics and consequences. In Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Dental Phobia; Öst, L.G., Skaret, E., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, T.; Assimakopoulou, K.; Daly, B.; Scambler, S.; Scott, S. The management of dental anxiety: Time for a sense of proportion. Br. Dent. J. 2012, 2013, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeberg, M.; Berggren, U.; Gröndahl, H.G. A radiographic study of dental health in adult patients with dental anxiety. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1993, 21, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jongh, A.; Aartman, I.H.; Brand, N. Trauma-related phenomena in anxious dental patients. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2003, 31, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berggren, U. General and specific fears in referred and self-referred adult patients with extreme dental anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 1992, 30, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohjola, V.; Mattila, A.K.; Joukamaa, M.; Lahti, S. Anxiety and depressive disorders and dental fear among adults in Finland. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 2011, 119, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wide Boman, U.; Lundgren, J.; Berggren, U.; Carlsson, S.G. Psychosocial and dental factors in the maintenance of severe dental fear. Swed. Dent. J. 2010, 34, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Berggren, U. Reduction of fear and anxiety in adult fearful patients. Int. Dent. J. 1987, 37, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lundgren, J.; Wide Boman, U. Multimodal cognitive behavior treatment. In Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Dental Phobia; Öst, L.G., Skaret, E., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, G.; Berggren, U.; Milgrom, P. Dental fear in adults: A meta-analysis of behavioral interventions. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2004, 32, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.; Heimberg, R.G.; Tellez, M.; Ismail, A.I. A critical review of approaches to the treatment of dental anxiety in adults. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armfield, J.M.; Heaton, L.J. Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: A review. Aust. Dent. J. 2013, 58, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wide Boman, U.; Carlsson, V.; Westin, M.; Hakeberg, M. Psychological treatment of dental anxiety among adults: A systematic review. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2013, 121, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berggren, U. Long-term effects of two different treatments for dental fear and avoidance. J. Dent. Res. 1986, 65, 874–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakeberg, M.; Berggren, U.; Carlsson, S.G. A 10-year follow-up of patients treated for dental fear. Scand. J. Dent. Res. 1990, 98, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hägglin, C.; Wide Boman, U. A dental phobia treatment within the Swedish National Health Insurance. Swed. Dent. J. 2012, 36, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Haukebo, K.; Skaret, E.; Ost, L.G.; Raadal, M.; Berg, E.; Sundberg, H.; Kvale, G. One- vs. five-session treatment of dental phobia: A randomized controlled study. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2008, 39, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öst, L.G. One-session treatment of dental phobia. In Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Dental Phobia; Öst, L.G., Skaret, E., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- De Jongh, A.; Muris, P.; ter Horst, G.; van Zuuren, F.; Schoenmakers, N.; Makkes, P. One-session cognitive treatment of dental phobia: Preparing dental phobics for treatment by restructuring negative cognitions. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Group | Root Remnants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| n = 148 | n = 63 | n = 85 | |

| Male/Female (%) | 39/61 | 38/62 | 40/60 |

| mean (sd) | mean (sd) | mean (sd) | |

| Age, years | 36.1 (9.9) | 33.7 (6.8) | 38.0 (11.3) * |

| Decayed teeth | 8.1 (5.2) | 6.0 (4.4) | 9.6 (5.2) ** |

| Missing teeth | 3.4 (4.0) | 2.1 (2.9) | 4.5 (4.3) ** |

| Filled teeth | 7.1 (4.8) | 7.7 (4.9) | 6.6 (4.7) |

| DMFT | 18.6 (5.6) | 15.7 (6.1) | 20.7 (4.9) ** |

| DAS | 17.2 (2.6) | 17.1 (2.5) | 17.3 (2.7) |

| DFS | 79.8 (12.5) | 79.0 (11.9) | 80.5 (13.0) |

| HAD-A | 12.4 (5.0) | 11.1 (4.8) | 13.3 (4.9) ** |

| HAD-D | 7.1 (4.2) | 5.8 (3.4) | 8.0 (4.5) ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wide, U.; Hakeberg, M. Treatment of Dental Anxiety and Phobia—Diagnostic Criteria and Conceptual Model of Behavioural Treatment. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9120153

Wide U, Hakeberg M. Treatment of Dental Anxiety and Phobia—Diagnostic Criteria and Conceptual Model of Behavioural Treatment. Dentistry Journal. 2021; 9(12):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9120153

Chicago/Turabian StyleWide, Ulla, and Magnus Hakeberg. 2021. "Treatment of Dental Anxiety and Phobia—Diagnostic Criteria and Conceptual Model of Behavioural Treatment" Dentistry Journal 9, no. 12: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9120153

APA StyleWide, U., & Hakeberg, M. (2021). Treatment of Dental Anxiety and Phobia—Diagnostic Criteria and Conceptual Model of Behavioural Treatment. Dentistry Journal, 9(12), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9120153