Brief Motivational Interviewing in Dental Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Why Use Motivational Interviewing (MI) in Clinical Practice?

2.1. Is MI Effective?

2.2. What Is MI?

3. MI in Practice

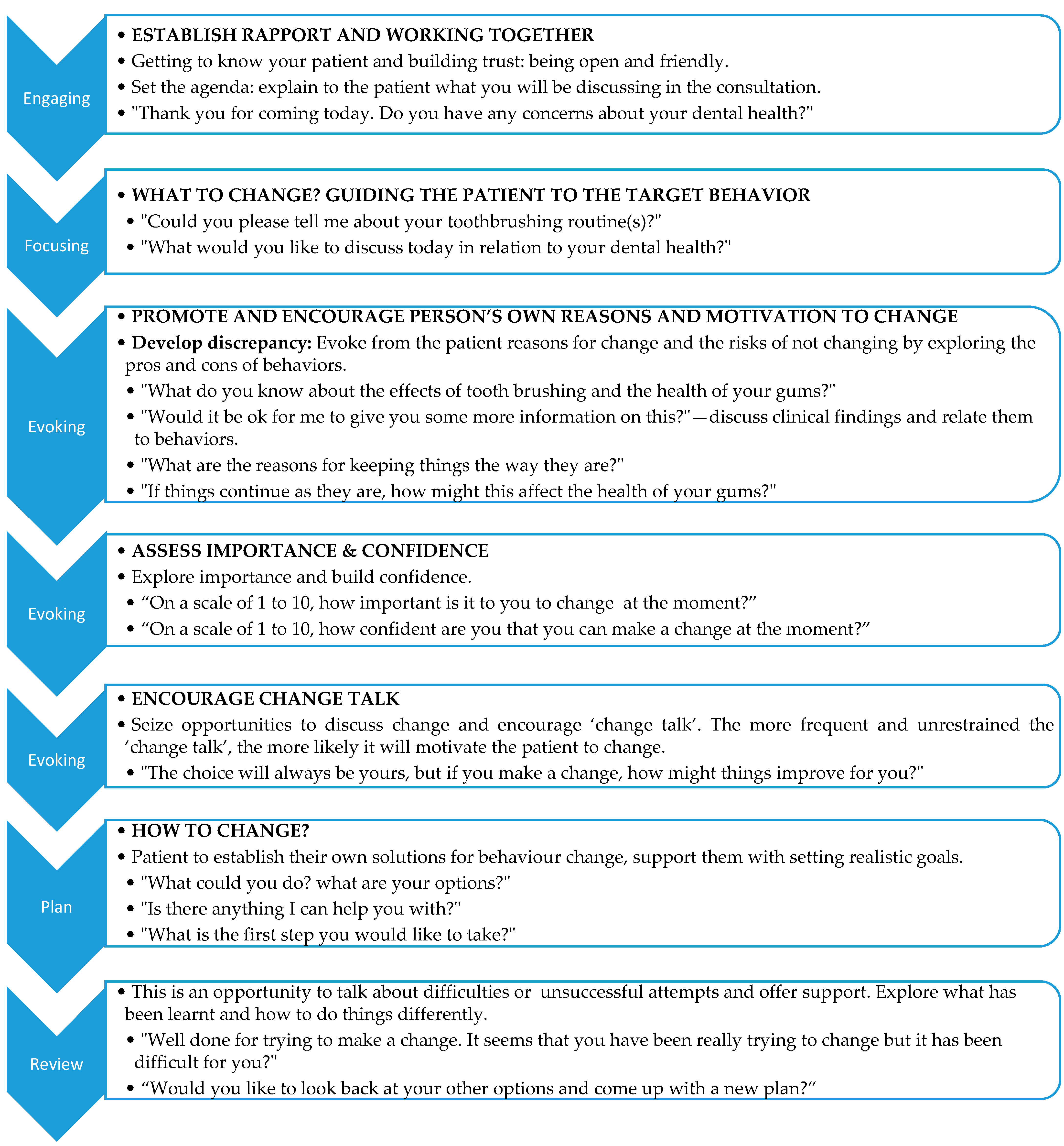

3.1. Engaging

3.2. Focusing

“It seems you are concerned about your gums bleeding today. Would you be happy to discuss this now?”

“Should we try to find out what is the cause of your gums bleeding?”

3.3. Evoking

“You seem to have a good awareness of what may affect the health of your gums and teeth. Would it be ok for me to tell you more about this? There are a couple of comments I could make…”

“It sounds like that you would like to stop smoking but you can’t at this stage…” Is this right?(Clarify what they have said)

“It seems that you would like to stop smoking but you feel you are not ready at this stage”

“If things continue as they are, how might this affect the health of your gums?”

“On a scale of 1 to 10, how confident are you that you could make this change if you wanted to?”

3.4. Planning:

- “Is there anything I can help you with?”

- “What is the first step you would like to take?”

3.5. Review

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. For Training on MI

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dyer, T.A.; Robinson, P.G. General health promotion in general dental practice—The involvement of the dental team Part 2: A qualitative and quantitative investigation of the views of practice principals in South Yorkshire. Br. Dent. J. 2006, 201, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chestnutt, I.G.; Binnie, V.I. Smoking cessation counselling—A role for the dental profession? Br. Dent. J. 1995, 179, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, J.H.; Thomas, D.; Richards, D. Smoking cessation interventions in the Oxford region: Changes in dentists’ attitudes and reported practices 1996–2001. Br. Dent. J. 2003, 195, 270–275, discussion 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, J.M.; Eccles, M.P.; Walker, A.E.; Thomas, R.E. Changing physicians’ behavior: What works and thoughts on getting more things to work. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2002, 22, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grol, R.; Wensing, M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med. J. Aust. 2004, 180, S57–S60. [Google Scholar]

- NICE. Oral Health Promotion: General Health Promotion: General Dental Dental Practice; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Golin, C.E.; Liu, H.; Hays, R.D.; Miller, L.G.; Beck, C.K.; Ickovics, J.; Kaplan, A.H.; Wenger, N.S. A prospective study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2002, 17, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Behaviour; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S.H.; Greenfield, S.; Ware, J.E., Jr. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med. Care 1989, 27, S110–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, J.P.; Ayala, G.X.; Harris, S. Theories and intervention approaches to health-behavior change in primary care. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1999, 17, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.; Garnett, S.P.; Baur, L.; Burrows, T.; Stewart, L.; Neve, M.; Collins, C. Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in child obesity: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e1647–e1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.; O’Rourke, P.; Del Mar, C.; Kenardy, J. Psychological interventions for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, E.; Hudson, S.M.; Blampied, N.M. Motivational interviewing in health settings: A review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2004, 53, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollnick, S.; Miller, W. What is motivational Interviewing? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 1995, 23, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Match Research Group. Project MATCH: Rationale and methods for a multi-site clinical trial matching patients to alcoholism treatment. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1993, 17, 1130–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotts, A.L.; Diclemente, C.C.; Dolan-Mullen, P. One-to-one: A motivational intervention for resistant pregnant smokers. Addict. Behav. 2002, 27, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, B.L.; Dunn, C.W.; Atkins, D.C.; Phelps, J.S. The emerging evidence base for motivational interviewing: A meta-analytic and qualitative inquiry. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2004, 19, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubak, S.; Sandbaek, A.; Lauritzen, T.; Christensen, B. Motivational interviewing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2005, 55, 305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl, B.; Burke, B.L. The Effectiveness and Applicability of Motivational Interviewing: A Practice-Friendly Review of Four Meta-Analyses. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 1232–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senft, R.; Polen, R.; Freeborn, D.; Hollis, J. Drinking Patterns and Health: A Randomized Trial of Screening and Brief Intervention in a Primary Care Setting; Center for Health Research: Portland, OR, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, C.C.; Rollnick, S.; Cohen, D.; Bachmann, M.; Russell, I.; Stott, N. Motivational consulting versus brief advice for smokers in general practice: A randomized trial. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 1999, 49, 611–616. [Google Scholar]

- Cascaes, A.M.; Bielemann, R.M.; Clark, V.L.; Barros, A.J.D. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing at improving oral health: A systematic review. Rev. Saude Publ. 2014, 48, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.L.; Lo, E.C.M.; Kot, S.C.C.; Chan, K.C.W. Motivational Interviewing in Improving Oral Health: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, S.L.; Ramseier, C.A.; Ratka-Krüger, P.; Woelber, J.P. Motivational Interviewing as an Adjunct to Periodontal Therapy—A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.R. Motivational Interviewing with Problem Drinkers. Behav. Psychother. 1983, 11, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg-Smith, S.M.; Stevens, V.J.; Brown, K.M.; Van, H.L.; Gernhofer, N.; Peters, E.; Greenberg, R.; Snetselaar, L.; Ahrens, L.; Smith, K. A brief motivational intervention to improve dietary adherence in adolescents. Health Educ. Res. 1999, 14, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midboe, A.M.; Cucciare, M.A.; Trafton, J.A.; Ketroser, N.; Chardos, J.F. Implementing motivational interviewing in primary care: The role of provider characteristics. Transl. Behav. Med. 2011, 1, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollnick, S.; Miller, W.R.; Butler, C. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.M.; Ramseier, C.A.; Mattheos, N.; Schoonheim-Klein, M.; Compton, S.; Al-Hazmi, N.; Polychronopoulou, A.; Suvan, J.; Antohe, M.E.; Forna, D.; et al. Education of tobacco use prevention and cessation for dental professionals—A paradigm shift. Int. Dent. J. 2010, 60, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2009, 37, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Mount, K.A. A Small Study of Training in Motivational Interviewing: Does One Workshop Change Clinician and Client Behavior? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2001, 29, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. Available online: https://motivationalinterviewing.org/ (accessed on 23 April 2019).

| OARS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gillam, D.G.; Yusuf, H. Brief Motivational Interviewing in Dental Practice. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj7020051

Gillam DG, Yusuf H. Brief Motivational Interviewing in Dental Practice. Dentistry Journal. 2019; 7(2):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj7020051

Chicago/Turabian StyleGillam, David G., and Huda Yusuf. 2019. "Brief Motivational Interviewing in Dental Practice" Dentistry Journal 7, no. 2: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj7020051

APA StyleGillam, D. G., & Yusuf, H. (2019). Brief Motivational Interviewing in Dental Practice. Dentistry Journal, 7(2), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj7020051