Prosthetic Status, Removable Prostheses and Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis Within a Population-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

Life Satisfaction vs. OHRQoL: Conceptual Distinction and Relevance

2. Materials and Methods

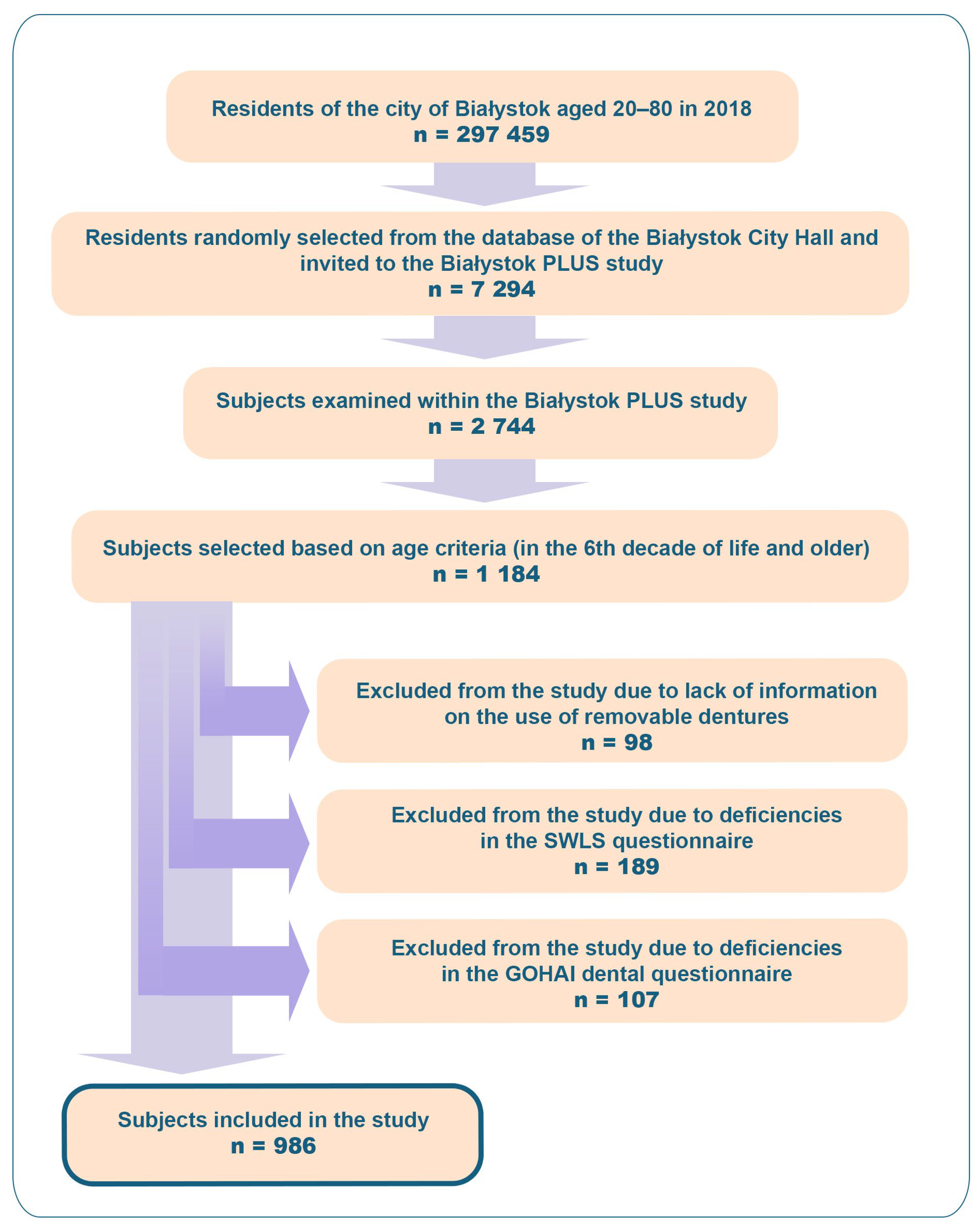

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Sample Selection

2.2.1. Age

2.2.2. Dental Data

2.2.3. Life Satisfaction and Quality of Life

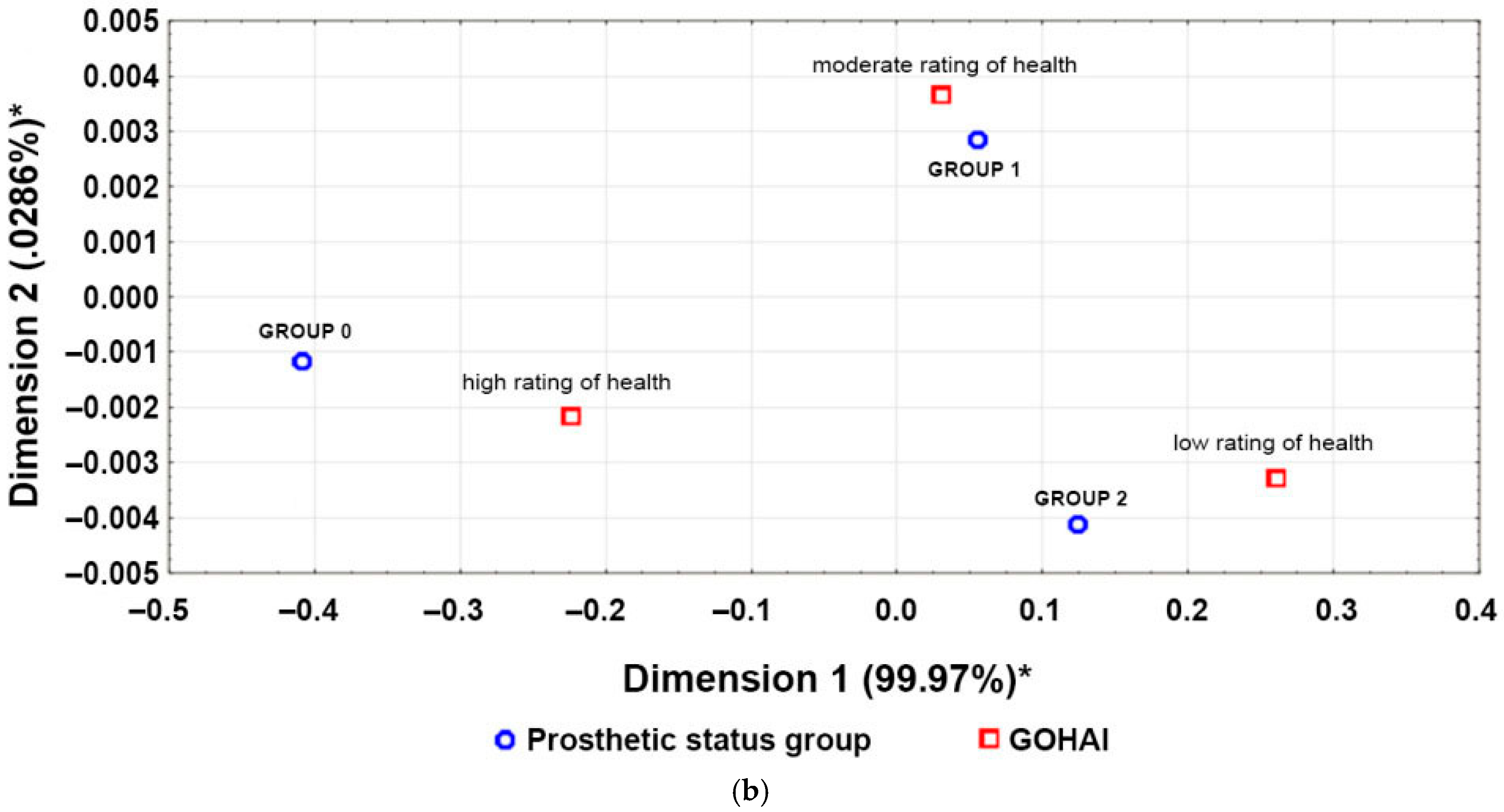

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prosthetic Status

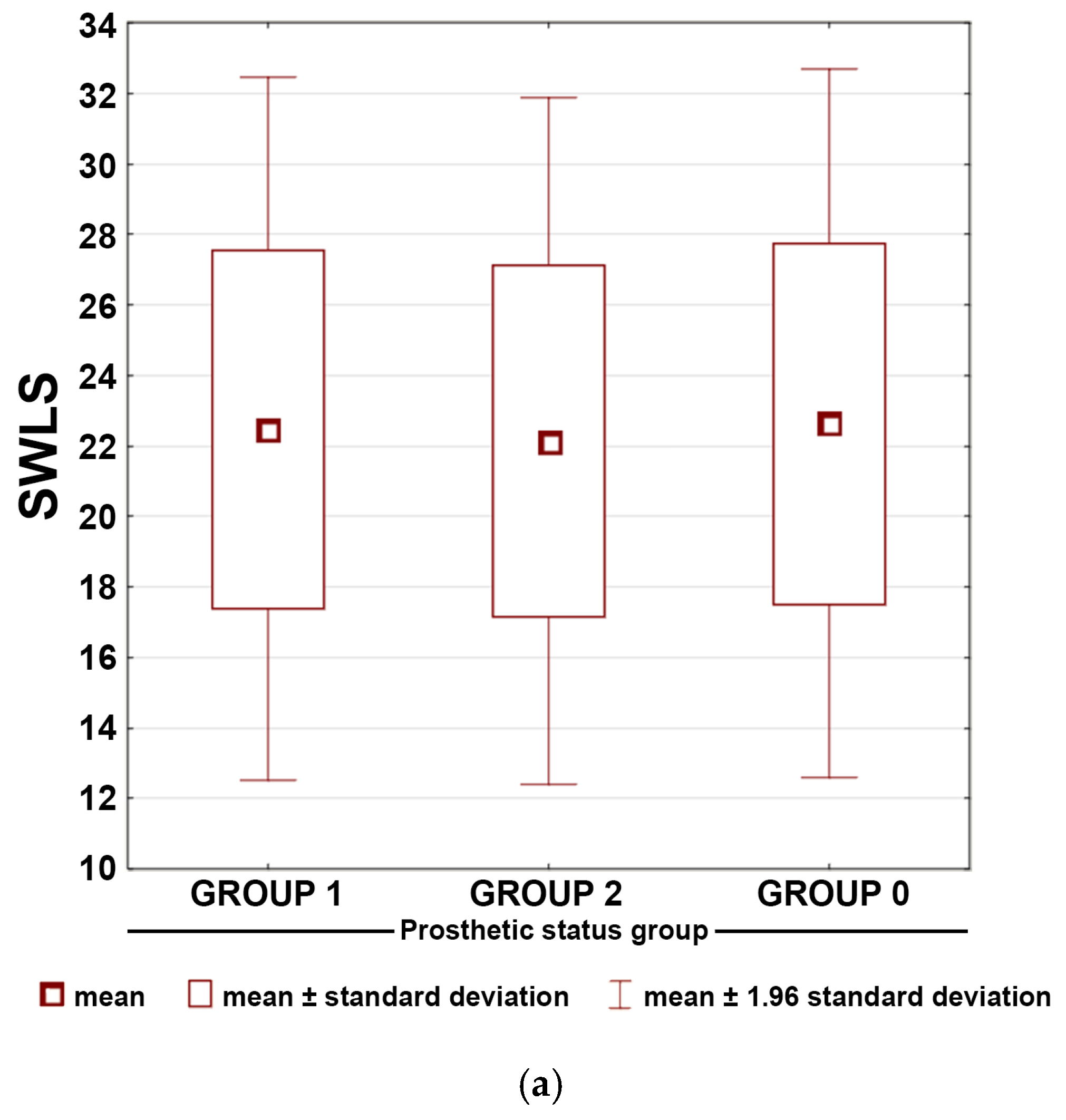

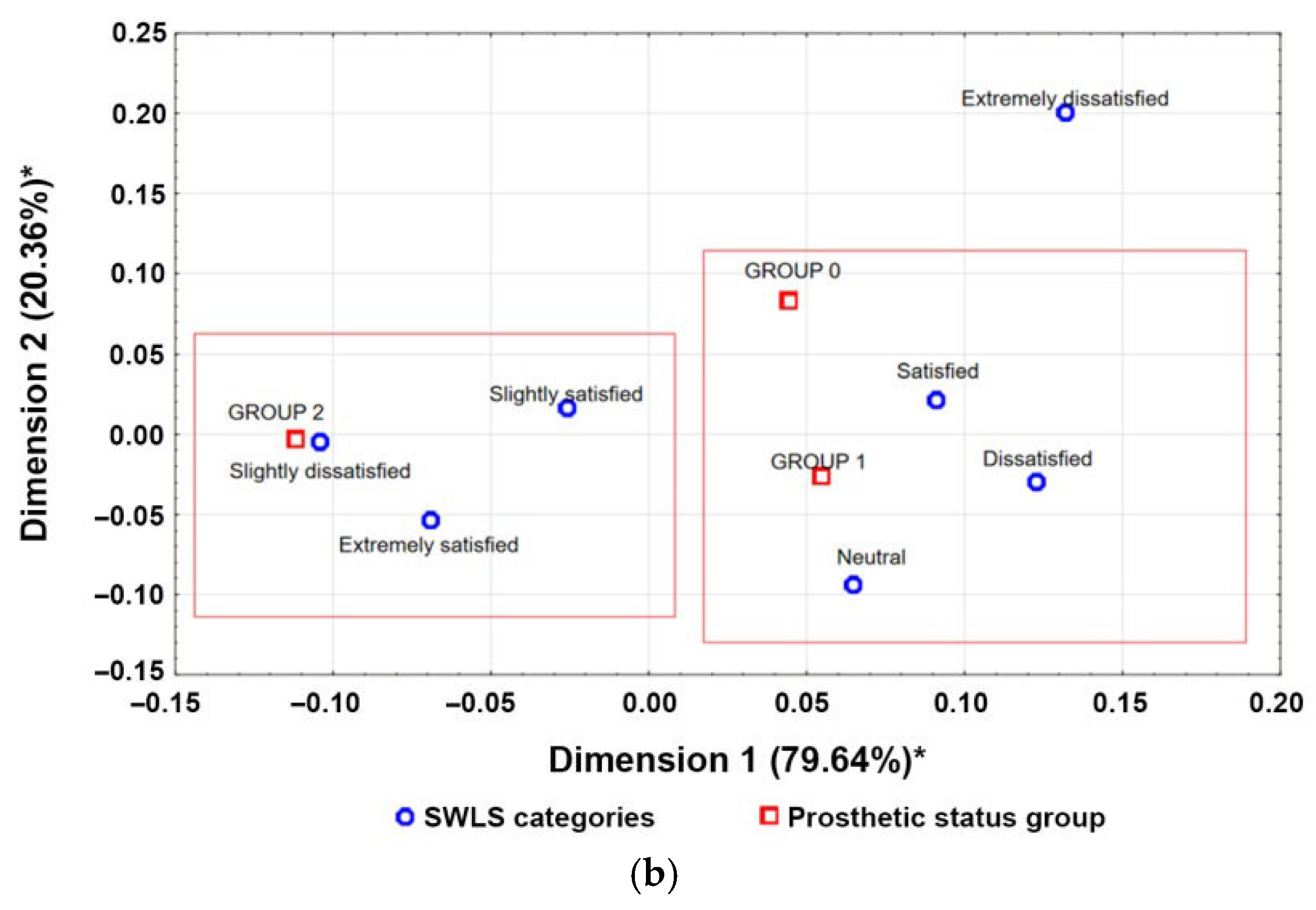

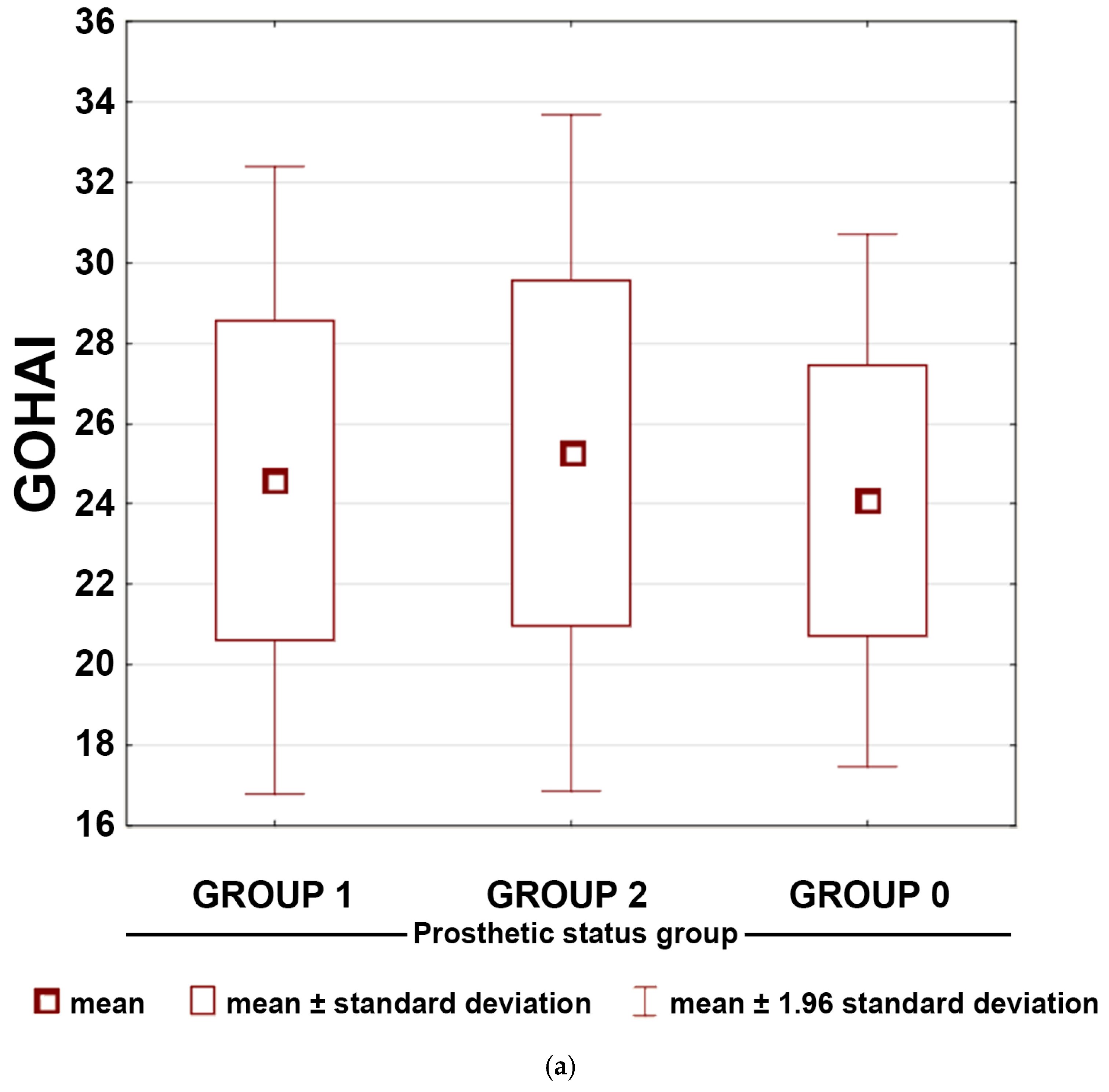

3.2. Prosthetic Status and Life Satisfaction

4. Discussion

4.1. Prosthetic Status Patterns in the Study Population

4.2. Life Satisfaction vs. Oral Health–Related Quality of Life

4.3. Interpretation of OHRQoL Differences and Functional Dentition

4.4. Dietary Limitations and Systemic Health

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

- Life satisfaction remained stable across all prosthetic groups, indicating that global well-being is not influenced by dental status or prosthesis use.

- OHRQoL differed significantly between groups, with the highest scores among participants without dental deficiencies.

- Users of removable dental prostheses reported the lowest OHRQoL, even lower than those with unreconstructed deficiencies.

- Mucosa-supported prostheses did not improve perceived oral health, suggesting limited effectiveness of this widely used rehabilitation method.

- Preservation of natural dentition is the strongest determinant of favourable OHRQoL, underscoring the importance of preventive and conservative care.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| DALYs | Disability-adjusted life years |

| OHRQoL | Oral health-related quality of life |

| RDPs | Removable dental prostheses |

| SWLS | Satisfaction with Life Scale |

| GOHAI | Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

References

- Matsuyama, Y.; Aida, J.; Watt, R.; Tsuboya, T.; Koyama, S.; Sato, Y.; Kondo, K.; Osaka, K. Dental status and compression of life expectancy with disability. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm-Pedersen, P.; Schultz-Larsen, K.; Christiansen, N.; Avlund, K. Tooth loss and subsequent disability and mortality in old age. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.; Izumi, M.; Furuta, M.; Takeshita, T.; Shibata, Y.; Kageyama, S.; Ganaha, S.; Yamashita, Y. Association between posterior teeth occlusion and functional dependence among older adults in nursing homes in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Iseki, C.; Igari, R.; Sato, H.; Sato, H.; Koyama, S.; Tobita, M.; Kawanami, T.; Iino, M.; et al. Tooth loss- associated cognitive impairment in the elderly: A community-based study in Japan. Intern. Med. 2019, 58, 1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, H.; Berglund, J.; Renvert, S. Tooth loss and cognitive functions among older adults. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2014, 72, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, J.L.F.; de Andrade, F.B.; Peres, M.A. How functional disability relates to dentition in community-dwelling older adults in Brazil. Oral. Dis. 2017, 23, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Min, J.-Y.; Lee, H.S.; Kwon, K.-R.; Yoo, J.; Won, C.W. The association between the number of natural remaining teeth and appendicular skeletal muscle mass in Korean older adults. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2018, 22, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bando, S.; Tomata, Y.; Aida, J.; Sugiyama, K.; Sugawara, Y.; Tsuji, I. Impact of oral self-care on incident functional disability in elderly Japanese: The Ohsaki Cohort 2006 study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Aida, J.; Kondo, K.; Fuchida, S.; Tani, Y.; Saito, M.; Sasaki, Y. Oral health and incident depressive symptoms: JAGES project longitudinal study in older Japanese. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.; McGowan, L.; McCrum, L.-A.; Cardwell, C.R.; McGuinness, B.; Moore, C.; Woodside, J.V.; McKenna, G. The impact of dental status on perceived ability to eat certain foods and nutrient intakes in older adults: Cross-sectional analysis of the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey 2008–2014. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcenes, W.; Steele, J.G.; Sheiham, A.; Walls, A.W.G. The relationship between dental status, food selection, nutrient intake, nutritional status, and body mass index in older people. Cad. Saude Publica 2003, 19, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanda, A.J.; Livinski, A.A.; London, S.D.; Boroumand, S.; Weatherspoon, D.; Iafolla, T.J.; Dye, B.A. Tooth retention, health, and quality of life in older adults: A scoping review. BMC Oral. Health 2022, 22, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, K.; Taylor, G.W.; Tahir, P.; Hyde, S. Association of tooth loss with morbidity and mortality by diabetes status in older adults: A systematic review. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2021, 21, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Smith, A.G.C.; Bernabé, E.; Fleming, T.D.; Reynolds, A.E.; Vos, T.; Murray, C.J.L.; Marcenes, W.; GBD 2015 Oral Health Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence, Incidence, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for Oral Conditions for 195 Countries, 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Oral Health 2023–2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090538 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Lyu, C.; Shang, Z.; Niu, A.; Liang, X. Quality of life of implant-supported overdenture and conventional complete denture in restoring the edentulous mandible: A systematic review. Implant. Dent. 2017, 26, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthys, C.; Vervaeke, S.; Besseler, J.; Doornewaard, R.; Dierens, M.; De Bruyn, H. Five years follow-up of mandibular 2-implant overdentures on locator or ball abutments: Implant results, patient-related outcome, and prosthetic aftercare. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.C.; Kawachi, I.; Souza, J.G.S.; Campos, F.L.; Chalub, L.L.F.H.; Antunes, J.L.F. Is reduced dentition with and without dental prosthesis associated with oral health-related quality of life? A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damyanov, N.D.; Witter, D.J.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Creugers, N.H. Satisfaction with the dentition related to dental functional status and tooth replacement in an adult Bulgarian population: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2013, 17, 2139–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, A.E.; Allen, P.F.; Witter, D.J.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Creugers, N.H. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Baker, S.R.; Shahrbaf, S.; Martin, N.; Vettore, M.V. Oral health-related quality of life after prosthodontic treatment for patients with partial edentulism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 121, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; De Haes, J.C.J.M.; et al. The European Oganization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, D.F.; Tulsky, D.S.; Gray, G.; Sarafian, B.; Linn, E.; Bonomi, A.; Silberman, M.; Yellen, S.B.; Winicour, P.; Brannon, J. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993, 11, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Healthy Ageing and Functional Ability. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/healthy-ageing-and-functional-ability (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Medical University of Bialystok Bialystok, PLUS. Available online: https://www.umb.edu.pl/en/mub_research_centres/bialystok_plus (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Shen, X.; Wang Ch Zhou, X.; Zhou, W.; Hornburg, D.; Wi, S.; Snyder, M.P. Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 1619–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. Development of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, K.A.; Dolan, T.A. Development of the geriatric Oral health assessment index. J. Dent. Educ. 1990, 54, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Z. Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia. Skala Satysfakcji z Życia; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warszawa, Poland, 2001; pp. 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Rodakowska, E.; Mierzyńska, K.; Bagińska, J.; Jamiołkowski, J. Quality of life measured by OHIP-14 and GOHAI in elderly people from Bialystok, north-east Poland. BMC Oral. Health 2014, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elm, E.v.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Correction to: Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 0–a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H. A nonparametric test for the several sample problem. Ann. Math. Stat. 1952, 23, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhuzali, T.; Beh, E.J.; Stojanovski, E. Multiple correspondence analysis as a tool for examining Nobel Prize data from 1901 to 2018. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khangar, N.V.; Kamalja, K.K. Multiple correspondence analysis and its applications. Electron. J. Appl. Stat. Anal. 2017, 10, 432–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszkowska, D. (Statistics Poland). The Situation of Older People in Poland in 2023. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/older-people/older-people/the-situation-of-older-people-in-poland-in-2023,1,6.html (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Suzuki, S.; Noda, T.; Nishioka, Y.; Myojin, T.; Kubo, S.; Imamura, T.; Kamijo, H.; Sugihara, N. Evaluation of public health expenditure by number of teeth among outpatients with diabetes mellitus. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 2021, 62, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samietz, S.A.; Kindler, S.; Schwahn, C.; Polzer, I.; Hoffmann, W.; Kocher, T.; Grabe, H.J.; Mundt, T.; Biffar, R. Impact of depressive symptoms on prosthetic status—Results of the study of health in Pomerania (SHIP). Clin. Oral. Investig. 2013, 17, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V.; Ashok, V.; Maiti, S. Quality of life post oral rehabilitation with complete short arch among South Indian patients. Bioinformation 2022, 18, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Peres, K.G.; Peres, M.A. Retention of Teeth and Oral Health–Related Quality of Life. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 1350–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamai-Homata, E.; Koletsi-Kounari, H.; Margaritis, V. Gender differences in oral health status and behavior of Greek dental students: A meta-analysis of 1981, 2000 and 2010 data. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2016, 6, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, D.M.; Kannan, A.; Venugopalan, S. Effect of Coated Surfaces influencing Screw Loosening in Implants: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World J. Dent. 2017, 8, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, N.K.; Wimmelmann, C.L.; Mortensen, E.L.; Flensborg-Madsen, T. Longitudinal associations of self-reported satisfaction with life and vitality with risk of mortality. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 147, 110529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowden, R.G.; Rueger, S.Y.; Davis, E.B.; Counted, V.; Kent, B.V.; Chen, Y.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Rim, M.; Lemke, A.W.; Worthington, E.L., Jr. Resource loss, positive religious coping, and suffering during the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective cohort study of US adults with chronic illness. Ment. Health Relig. Cultur. 2022, 25, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, D. Age and life satisfaction: Getting control variables under control. Sociology 2022, 55, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, M.; Jovanović, V. Similarities and differences in predictors of life satisfaction across age groups: A 150-country study. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Kim, E.S.; Cao, C.; Allen, T.D.; Cooper, C.L.; Lapierre, L.M.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Sanchez, J.I.; Spector, P.E.; Poelmans, S.A.Y.; et al. Measurement invariance of the Satisfaction with Life Scale across 26 countries. J. Cross-Cultur. Psychol. 2017, 48, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Bustamante, J.; Barón-López, F.J.; Carmona-González, F.J.; Pérez-Farinós, N.; Wärnberg, J. Validation of a modified version of the Spanish Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI-SP) for adults and elder people. BMC Oral. Health 2020, 20, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosun, B.; Uysal, N. Examination of oral health quality of life and patient satisfaction in removable denture wearers with OHIP-14 scale and visual analog scale: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral. Health 2024, 24, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.H.; Li, L.; Jia, S.L.; Li, Q.; Hao, J.-X.; Ma, S.; He, Z.-K.; Wan, Q.-Q.; Cai, Y.-F.; Li, Z.-T.; et al. Association of Tooth Loss and Diet Quality with Acceleration of Aging: Evidence from NHANES. Am. J. Med. 2023, 136, 773–779.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, G.G.F.; Xu, H.; Spence, L.A.; Patel, P.; Bualteng, V.; Cheriyan, B.; Clark, D.O.; Gletsu-Miller, N.A.; Thyvalikakath, T.P. Assessing the nutrient intake and diet quality of adults wearing dentures using the healthy eating index. BMC Oral. Health 2025, 25, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, R.; Abe, Y.; Kusumoto, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Yokoi, T.; Sako, H.; Baba, K. Factors Associated with Nutritional Status in Patients with Removable Dentures: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e75288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Prosthetic Status |

|---|---|

| 0 | No dental deficiencies or deficiencies restored with fixed/non-removable prosthetic restorations, i.e., prosthetic crown supported by own tooth or implant, bridge, onlay or overlay restoration |

| 1 | Dental deficiencies without prosthetic restoration |

| 2 | Dental deficiencies restored with removable prostheses, i.e., full or partial dentures (mucosa-supported), metal framework dentures (tooth support), implant supported dentures |

| Prosthetic Status Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n/%) | 0—Without Dental Deficiencies (n/%) | 1—Dental Deficiencies Not Prosthetically Rehabilitated (n/%) | 2—Dental Deficiencies Using Removable Prostheses (n/%) | |

| 986/100 | 163/16.53 | 512/51.93 | 311/31.54 | |

| Women | 563/57.1 | 92/56.44 | 268/52.34 | 203/65.27 |

| Men | 423/42.9 | 71/43.56 | 244/47.66 | 108/34.73 |

| Retired | 489/49.59 | 34/20.86 | 244/47.66 | 211/67.84 |

| Pensioner | 16/1.62 | 2/1.23 | 9/1.76 | 5/1.61 |

| Employed | 433/43.91 | 115/70.55 | 233/45.51 | 85/27.33 |

| Unemployed | 48/4.87 | 12/7.36 | 26/5.08 | 10/3.21 |

| Age 50–59 | 344/34.89 | 109/66.88 | 184/35.93 | 51/16.40 |

| Age 60–69 | 429/43.51 | 47/28.83 | 230/44.92 | 152/48.87 |

| Age 70–82 | 213/21.40 | 7/4.29 | 98/19.13 | 108/34.73 |

| Partial Dental Deficiency in the Maxilla (n/% of All Participants) | Partial Dental Deficiency in the Mandible (n/% of All Participants) | Complete Dental Deficiency in the Maxilla (n/% of All Participants) | Complete Dental Deficiency in the Mandible (n/% of All Participants) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not applicable | 416/42.20 | 325/32.95 | 853/86.50 | 903/91.57 |

| Mucosa-supported | 211/21.40 | 145/14.72 | 116/11.76 | 67/6.80 |

| Tooth-supported | 86/8.71 | 86/8.72 | 2/0.20 | 3/0.30 |

| Implant-supported | 2/0.20 | 2/0.20 | 1/0.10 | 1/0.10 |

| Dental deficiencies unrestored | 271/27.49 | 428/43.41 | 14/1.44 | 12/1.23 |

| SWLS Questionnaire | Group 0 | Group 1 | Group 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. In most aspects, my life is close to my ideal. | 4.05 | 4.00 | 4.01 | |

| 2. The conditions of my life are excellent. | 4.61 | 4.59 | 4.63 | |

| 3. I am satisfied with my life. | 5.01 | 5.00 | 4.89 | |

| 4. So far I have gotten the important things I want in life. | 4.82 | 4.72 | 4.50 | |

| 5. If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. | 4.13 | 4.17 | 4.11 | |

| Total | 22.60 | 22.45 | 22.13 |

| GOHAI Questionnaire | Group 0 | Group 1 | Group 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How often do you limit the kind or amount of food you eat because of problems with your teeth or dentures? | 4.86 | 4.77 | 4.72 | |

| 2. How often do you have trouble biting or chewing any kind of food such as firm meat or apples? | 4.77 | 4.37 | 3.91 | |

| 3. How often are you able to swallow comfortably? | 4.93 | 4.72 | 4.74 | |

| 4. How often do your teeth or dentures prevent you from speaking the way you want? | 4.94 | 4.80 | 4.74 | |

| 5. How often are you able to eat anything without feeling discomfort? | 4.15 | 3.94 | 3.95 | |

| 6. How often do you limit contact with people because of the condition of your teeth or dentures? | 4.98 | 4.91 | 4.90 | |

| 7. How often are you pleased or happy with the appearance of your teeth and gums or dentures? | 3.80 | 3.15 | 3.30 | |

| 8. How often do you use medication to relieve pain or discomfort around your mouth? | 4.90 | 4.85 | 4.76 | |

| 9. How often are you worried or concerned about problems with your teeth, gums or dentures? | 4.50 | 4.14 | 4.19 | |

| 10. How often do you feel nervous or self-conscious because of problems with your teeth, gums or dentures? | 4.77 | 4.53 | 4.50 | |

| 11. How often do you feel uncomfortable eating in front of people because of problems with your teeth or dentures? | 4.92 | 4.73 | 4.64 | |

| 12. How often are your teeth or gums sensitive to hot, cold or sweets? | 4.15 | 4.13 | 4.36 | |

| Total | 55.67 | 53.04 | 52.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wnorowska, K.; Dębkowska, K.; Borawska, Z.; Samietz, S.; Bagińska, J.; Kamińska, I.; Dubatówka, M.; Stachurska, Z.; Sowa, P.; Kamiński, K.A.; et al. Prosthetic Status, Removable Prostheses and Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis Within a Population-Based Study. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010007

Wnorowska K, Dębkowska K, Borawska Z, Samietz S, Bagińska J, Kamińska I, Dubatówka M, Stachurska Z, Sowa P, Kamiński KA, et al. Prosthetic Status, Removable Prostheses and Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis Within a Population-Based Study. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleWnorowska, Kinga, Katarzyna Dębkowska, Zuzanna Borawska, Stefanie Samietz, Joanna Bagińska, Inga Kamińska, Marlena Dubatówka, Zofia Stachurska, Paweł Sowa, Karol A. Kamiński, and et al. 2026. "Prosthetic Status, Removable Prostheses and Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis Within a Population-Based Study" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010007

APA StyleWnorowska, K., Dębkowska, K., Borawska, Z., Samietz, S., Bagińska, J., Kamińska, I., Dubatówka, M., Stachurska, Z., Sowa, P., Kamiński, K. A., & Nowosielska, M. (2026). Prosthetic Status, Removable Prostheses and Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis Within a Population-Based Study. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010007