Prophylactic Antibiotic Therapy in Cleft Surgery—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

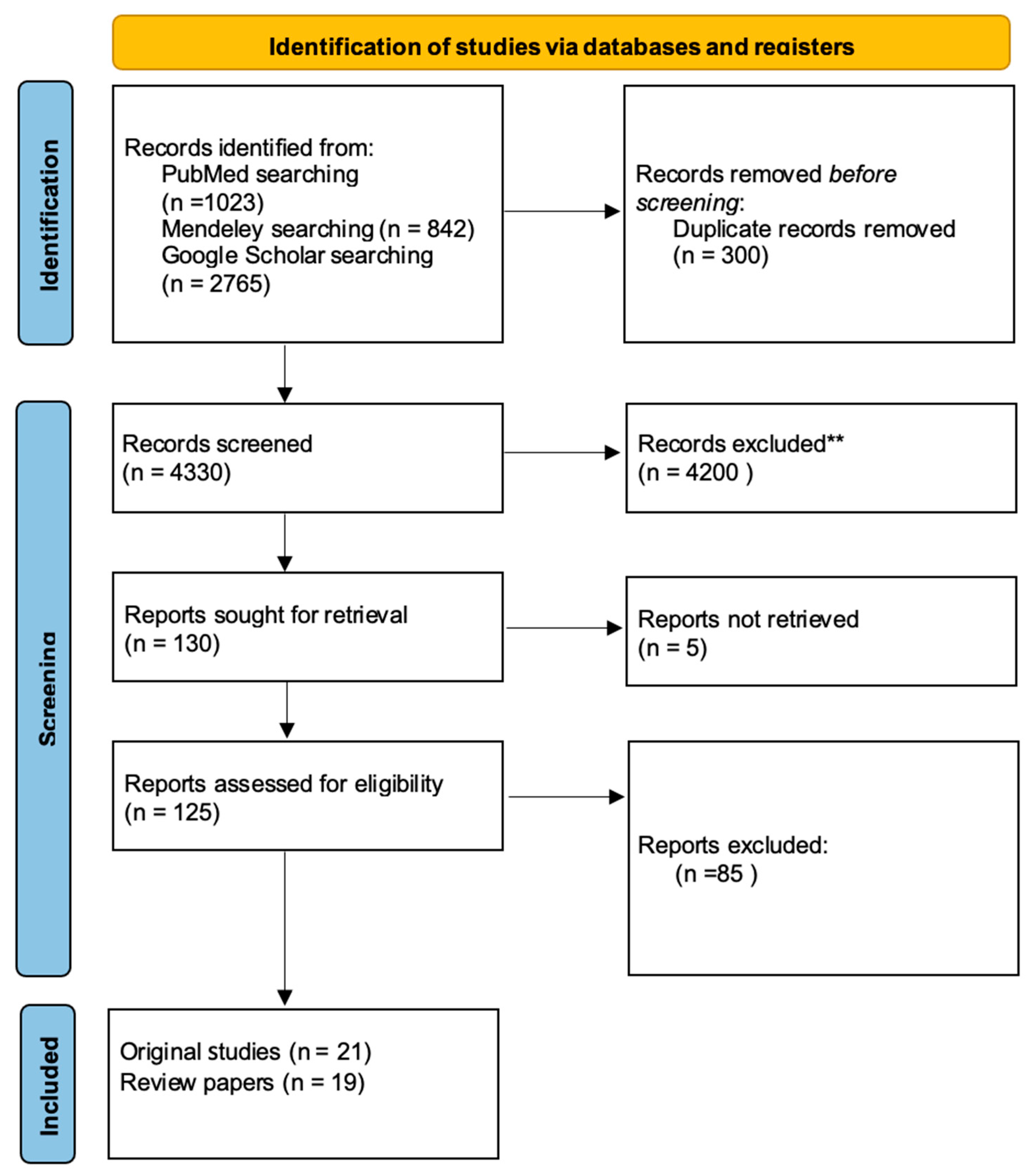

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Oral Pathogens in Concomitant Cleft Defects

4.2. Antibiotic Prevention in Isolated Defects

4.3. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Cleft Lip and Palate Defect

4.4. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Defects Requiring Bone Tissue Transplantation

4.5. Mouthwash Solutions Used in Perioperative Management

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: https://eu-rd-platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/eurocat/eurocat-data/prevalence_en (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Nasreddine, G.; El Hajj, J.; Ghassibe-Sabbagh, M. Orofacial clefts embryology, classification, epidemiology, and genetics. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2021, 787, 108373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babai, A.; Irving, M. Orofacial Clefts: Genetics of Cleft Lip and Palate. Genes 2023, 14, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inchingolo, A.M.; Fatone, M.C.; Malcangi, G.; Avantario, P.; Piras, F.; Patano, A.; Di Pede, C.; Netti, A.; Ciocia, A.M.; De Ruvo, E.; et al. Modifiable Risk Factors of Non-Syndromic Orofacial Clefts: A Systematic Review. Children 2022, 9, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantar, R.S.; Hamdan, U.S.; Muller, J.N.; Hemal, K.; Younan, R.A.; Haddad, M.; Melhem, A.M.; Griot, J.P.W.D.; Breugem, C.C.; Mokdad, A.H. Global Prevalence and Burden of Orofacial Clefts: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2023, 34, 2012–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Roey, V.L.; Mink van der Molen, A.B.; Mathijssen, I.M.J.; Akota, I.; de Blacam, C.; Breugem, C.; Matos, E.C.; Dávidovics, K.; Dissaux, C.; Dowgierd, K.; et al. Between unity and disparity: Current treatment protocols for common orofacial clefts in European expert centres. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 54, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olawoye, O.A.; Michael, A.I.; Olusanya, A. Perioperative Antibiotic Therapy in Orofacial Cleft Surgery. What Is the Consensus? Ann. Ib. Postgrad. Med. 2020, 18, S51–S57. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, A.G.; Knepil, G.J. Prophylactic antibiotics and surgery for primary clefts. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 46, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottgers, S.A.; Camison, L.; Mai, R.; Shakir, S.; Grunwaldt, L.; Nowalk, A.J.; Natali, M.; Losee, J.E. Antibiotic Use in Primary Palatoplasty: A Survey of Practice Patterns, Assessment of Efficacy, and Proposed Guidelines for Use. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccillo, E.M.; Farsar, C.J.; Holmes, D.M. Prophylactic Antibiotics After Cleft Lip and Palate Reconstruction: A Review from a Global Health Perspective. Cureus 2023, 15, e36371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.C.; Boriollo, M.F.G.; Souza, A.C.; da Silva, T.A.; da Silva, J.J.; Magalhães-Guedes, K.T.; Dias, C.T.d.S.; Bernardo, W.L.d.C.; Höfling, J.F.; de Sousa, C.P. Oral Staphylococcus Species and MRSA Strains in Patients with Orofacial Clefts Undergoing Surgical Rehabilitation Diagnosed by MALDI-TOF MS. Pathogens 2024, 13, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenske, F.; Stoltze, A.; Neuhaus, M.; Zimmerer, R.; Häfner, J.; Kloss-Brandstätter, A.; Lethaus, B.; Sander, A.K. Evaluating the efficacy of single-shot versus prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis in alveolar cleft osteoplasty—A retrospective cohort study. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 51, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittermann, G.K.P.; van Es, R.J.J.; de Ruiter, A.P.; Frank, M.H.; Bittermann, A.J.N.; van der Molen, A.B.M.; Koole, R.; Rosenberg, A.J.W.P. Incidence of complications in secondary alveolar bone grafting of bilateral clefts with premaxillary osteotomy: A retrospective cohort study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, J.; Levring Jäghagen, E.; Sjöström, M. Outcome after secondary alveolar bone grafting among patients with cleft lip and palate at 16 years of age: A retrospective study. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2021, 132, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tache, A.; Mommaerts, M.Y. Success rate of mid-secondary alveolar cleft reconstruction using anterior iliac bone grafts: A retrospective study. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 12, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluba, S.; Reinert, S.; Krimmel, M. Single-dose versus prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis for alveolar bone grafting in cleft patients. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 52, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, N.; Kapoor, S.; Cobb, A.; McLean, N.; David, D.; Chummun, S. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of fistulae in cleft palate repair: A quality improvement study. JPRAS Open 2024, 43, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, A.; Davies, A.; Main, B.; Wren, Y.M.; Deacon, S.M.; Cobb, A.F.; McLean, N.B.; David, D.A.; Chummun, S.M. Association of Perioperative Antibiotics with the Prevention of Postoperative Fistula after Cleft Palate Repair. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2024, 12, e5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodeh, D.S.; Nguyen, A.T.H.; Cray, J.J.; Rottgers, S.A. The Use of Prophylactic Antibiotics before Primary Palatoplasty Is Not Associated with Lower Fistula Rates: An Outcome Study Using the Pediatric Health Information System Database. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 144, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.R.; Reddy, S.G.; Banala, B.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Kummer, A.W.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M.; Bergé, S.J. Placement of an antibiotic oral pack on the hard palate after primary cleft palatoplasty: A randomized controlled trial into the effect on fistula rates. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 1953–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzman, T.J.; Verhey, E.M.; Kirschner, R.E.; Pollard, S.H.; Baylis, A.L.; Chapman, K.L. Cleft Outcomes Research NETwork (CORNET) Consortium. Cleft Palate Repair Postoperative Management: Current Practices in the United States. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2024, 61, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönmeyr, B.; Wendby, L.; Campbell, A. Early Surgical Complications After Primary Cleft Lip Repair: A Report of 3108 Consecutive Cases. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2015, 52, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preidl, R.H.M.; Kesting, M.; Rau, A. Perioperative Management in Patients with Cleft Lip and Palate. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2020, 31, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, M.; Davies, A.; Davies, A.; Chummun, S.; Cobb, A.R.; Moar, K.; Wren, Y. Current Surgical Practice for Children Born with a Cleft lip and/or Palate in the United Kingdom. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2023, 60, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roode, G.J.; Bütow, K.W. A Descriptive Study of Chlorhexidine as a Disinfectant in Cleft Palate Surgery. Clin. Med. Res. 2018, 16, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moaddabi, A.; Soltani, P.; Rengo, C.; Molaei, S.; Mousavi, S.J.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Spagnuolo, G. Comparison of antimicrobial and wound-healing effects of silver nanoparticle and chlorhexidine mouthwashes: An in vivo study in rabbits. Odontology 2022, 110, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomete, B.; Saheeb, B.D.; Obiadazie, A.C. A prospective clinical evaluation of the effects of chlorhexidine, warm saline mouth washes and microbial growth on intraoral sutures. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2015, 14, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aznar, M.L.; Schönmeyr, B.; Echaniz, G.; Nebeker, L.; Wendby, L.; Campbell, A. Role of Postoperative Antimicrobials in Cleft Palate Surgery: Prospective, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Study in India. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 136, 59e–66e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narinesingh, S.P.; Whitby, D.J.; Davenport, P.J. Moraxella catarrhalis: An unrecognized pathogen of the oral cavity? Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2011, 48, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleda, V.; Elsouri, K.N.; Heiser, S.E.; Bernal, I.; Kesselman, M.M.; Demory Beckler, M. Oral Microbiome as a Tool of Systemic Disease on Cleft Patients: A New Landscape. Cureus 2023, 15, e35444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, M.J.; Musavi, L.; Wang, M.M.; Haveles, C.S.; Liu, C.; Rezzadeh, K.S.; Lee, J.C. Oral Flora and Perioperative Antimicrobial Interventions in Cleft Palate Surgery: A Review of the Literature. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2021, 58, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Arregocés, F.; Eras, M.A.; Bustos, A.; Suárez-Castillo, A.; García-Robayo, D.A.; Del Pilar Bernal, M. Characterization of the oral microbiota and the relationship of the oral microbiota with the dental and periodontal status in children and adolescents with nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świtała, J.; Sycińska-Dziarnowska, M.; Spagnuolo, G.; Woźniak, K.; Mańkowska, K.; Szyszka-Sommerfeld, L. Oral Microbiota in Children with Cleft Lip and Palate: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratzler, D.W.; Dellinger, E.P.; Olsen, K.M.; Perl, T.M.; Auwaerter, P.G.; Bolon, M.K.; Fish, D.N.; Napolitano, L.M.; Sawyer, R.G.; Slain, D.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Surg. Infect. 2013, 14, 73–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milic, T.; Raidoo, P.; Gebauer, D. Antibiotic prophylaxis in oral and maxillofacial surgery: A systematic review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, I. Update on bacteraemia related to dental procedures. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2008, 39, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimdahl, A.; Hall, G.; Hedberg, M.; Sandberg, H.; Söder, P.; Tunér, K.; Nord, C. Detection and quantitation by lysis-filtration of bacteremia after different oral surgical procedures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990, 28, 2205–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouly, I.; Braun, R.S.; Silvestre, T.; Musa, W.; Miron, R.J.; Demyati, A. Efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in intraoral bone grafting procedures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, R.; Jain, P.; Saha, S.; Sarkar, S. Cleft lip and cleft palate: Role of a pediatric dentist in its management. Int. J. Pedod. Rehabil. 2017, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinero, L.; Blum, J.D.; Wagner, C.S.; Barrero, C.E.; Pontell, M.E.; Swanson, J.W.; Bartlett, S.P.; Taylor, J.A. Word of Mouth: Local Antisepsis Practices in Orthognathic Surgery and Opportunities for Innovation. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2024, 61, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Title | Year of Publication | Country | Type of Study | Patients and Methods | Number of Participants | Middle Age | Type of Cleft | Type of Intervention | Results, Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Staphylococcus Species and MRSA Strains in Patients with Orofacial Clefts Undergoing Surgical Rehabilitation Diagnosed by MALDI-TOF MS. [12] | 2024 | Brazil | original research | The study involved 59 patients from whom saliva samples were collected between hospitalizations. The samples were sent for microbiological diagnostics. | 59 (17 female, 42 male patients) | mean of 10.1 ± 14.6 years old | Cleft lip palate | observation (microbiological swabs) | The study found various Staphylococcus species, including MRSA strains, in the saliva of cleft patients, confirming increased bacterial colonization. |

| Evaluating the efficacy of single-shot versus prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis in alveolar cleft osteoplasty: a retrospective cohort study. [13] | 2023 | Germany | original research | The study involved 83 patients divided into two groups. The study group received prophylactic antibiotic therapy for 4 days of the postoperative period, while the control group received one dose of antibiotics after surgery. | 83 (46 male, 37 female patients) | mean age 12.8 years | Left-sided cleft lip and palate (49.5%), right-sided cleft lip and palate (25.3%), bilateral cleft lip and palate (24.2%), isolated cleft palate (1.1%) | observation | There was no significant difference in the rate of complications between single and prolonged antibiotic therapy, suggesting no benefit from longer treatment. |

| Incidence of complications in secondary alveolar bone grafting of bilateral clefts with premaxillary osteotomy: a retrospective cohort study. [14] | 2020 | Netherlands | original research | The study group consisted of 64 people who underwent SABG + PO surgery and were then given prophylactic antibiotics three times daily from the start of surgery and for 3 days postoperatively. | 64 (26 female, 38 male patients) | mean age 11.37 years | bilateral cleft lip and palate | surgery | In the group of 64 patients, a significant correlation was found between the frequency of complications and the timing of the bone graft relative to the patient’s age at the time of surgery. |

| Outcome after secondary alveolar bone grafting among patients with cleft lip and palate at 16 years of age: a retrospective study. [15] | 2021 | Sweden | original research | The study included 91 patients with 100 cleft sites, treated with autogenous bone grafts. All patients were administered intravenous antibiotics immediately preoperatively and during the next 24 h. | 91 | 16 years old | cleft palate- unilateral (82 patients); bilateral (9 patients) | observation | Most patients achieved stable graft integration and good functional outcomes, and complications were rare. Routine 24-h antibiotic therapy proved sufficient. |

| Success rate of mid-secondary alveolar cleft reconstruction using anterior iliac bone grafts: a retrospective study. [16] | 2022 | Belgium | original research | A retrospective cohort study was performed. A total of 124 patients were included and grouped as those primarily receiving a two-staged palatoplasty protocol and those receiving a one-staged protocol. | 124 (48 female and 76 male patients) | First group average age 9.7 years, second group average age 11.5 years | 73 had Veau III clefts, and 35 had Veau IV clefts; 15 patients had unilateral lip and alveolar clefts; 1 bilateral lip and alveolar clefting. | surgery | Bone reconstruction from the iliac crest showed high efficacy regardless of the palatoplasty protocol. |

| Single-dose versus prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis for alveolar bone grafting in cleft patients. [17] | 2023 | Germany | original research | The study included 109 patients divided into two groups: the research group received prophylactic antibiotic therapy for 2–11 days (median 5 days), and the control group received 1 dose of antibiotics preoperatively. | 94 (57 male, 37 female patients) | Average age 11.5 years old | cleft lip and palate (84), cleft alveolus (16%) | observation | Limiting antibiotic prophylaxis to a single dose did not lead to a higher infection rate. These findings provide strong evidence in favor of minimizing antibiotic use in alveolar bone grafting procedures for patients with clefts. |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of fistulae in cleft palate repair: A quality improvement study. [18] | 2025 | United Kingdom | retrospective cohort study | The study involved 97 patients divided into two groups. The research group received prophylactic antibiotic therapy for 7 days after surgery, and the control group received one dose of antibiotics preoperatively. | 97 (58 male, 39 female patients) | Average age 16.6 months | cleft palate: Veau 1 (11.1%), Veau 2 (57.4%), Veau 3 (20.3%), Veau 4 (11.2%) | observation | Extended antibiotic therapy did not significantly reduce the incidence of fistulas compared with a single dose. The results indicate that the duration of therapy does not affect the risk of complications. |

| Association of Perioperative Antibiotics with the Prevention of Postoperative Fistula after Cleft Palate Repair. [19] | 2024 | United Kingdom | retrospective cohort study | The analyses used 2136 surgical questionnaires completed at the time of palate repair in 1881 patients. | 1881 | Between 4.9 and 11.8 years old | cleft palate | observation | Prolonged antibiotic therapy did not significantly reduce the incidence of fistulas compared to a single dose. There was no evidence to suggest a difference in the incidence of fistulas between patients receiving amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid and those receiving an alternative antibiotic. |

| The Use of Prophylactic Antibiotics before Primary Palatoplasty Is Not Associated with Lower Fistula Rates: An Outcome Study Using the Pediatric Health Information System Database. [20] | 2019 | USA | retrospective cohort study | Retrospective study analyzed data from 7160 patients. Two different analysis models were performed. The first model included the patients who were given preoperative antibiotics, postoperative antibiotics and none. The second model included the patients who were given preoperative antibiotics. | 7160 | Mean age 11.5 years old | cleft palate | observation | The results showed that the use of pre- or postoperative antibiotic therapy did not significantly reduce the rate of fistulas as a complication of surgery. |

| Placement of an antibiotic oral pack on the hard palate after primary cleft palatoplasty: a randomized controlled trial into the effect on fistula rates. [21] | 2018 | India | retrospective cohort study | Study group consisted of two groups of 100 patients each, who underwent primary palatoplasty. Group A had an oral pack placed on the hard palate for 5 days postoperatively while group B (control) did not. | 200 | Between 12 and 13 months of age | non-syndromic complete unilateral cleft lip and palate with a previously repaired cleft lip | observation | The use of an antibiotic-impregnated dressing significantly reduced the incidence of fistulas. |

| Cleft Palate Repair Postoperative Management: Current Practices in the United States. [22] | 2022 | USA | survey study | A survey about postoperative management was administered to 67 cleft surgeons. | - | - | - | survey | The survey revealed significant variation in postoperative practices across the US, particularly regarding antibiotics and hygiene recommendations. Uniform guidelines are lacking. |

| Early Surgical Complications After Primary Cleft Lip Repair: A Report of 3108 Consecutive Cases. [23] | 2015 | India | retrospective cohort study | The medical records of 3108 consecutive lip repairs with 2062 follow-ups were reviewed retrospectively. | 2062 | Median 7 years old | cleft lip | surgery | The study showed that the incidence of wound infections can be kept relatively low even without the use of postoperative antibiotics. |

| Perioperative Management in Patients With Cleft Lip and Palate. [24] | 2020 | Germany | survey study | A survey was administered to members of 70 international cleft centers. | - | - | - | survey | An international survey revealed significant heterogeneity in perioperative protocols, including antibiotic use. Practices varied between centers and countries. |

| Prophylactic antibiotics and surgery for primary clefts. [8] | 2008 | United Kingdom | survey study | A survey was administered to 27 surgeons who were doing primary cleft lip surgery. | - | - | - | survey | The study showed a highly diverse approach among surgeons to the use of antibiotics in primary surgeries and the need to implement a standardized protocol for the implementation of prophylactic antibiotic therapy. |

| Current Surgical Practice for Children Born with a Cleft Lip and/or Palate in the United Kingdom. [25] | 2023 | United Kingdom | prospective cohort study | The study was based on 1782 surgical forms, related to 1514 patients with primary surgeries. | 1514 | Mean age for cheiloplasty 4.3 months; mean age for intravelar veloplasty 10.3 months | cleft lip; cleft palate | surgery | An analysis of procedures revealed significant differences in surgical techniques and approaches to prevention. Antibiotic therapy was used in 96% of cases, but the duration varied depending on the type of treatment. |

| Between unity and disparity: current treatment protocols for common orofacial clefts in European expert centers. [6] | 2024 | Netherlands | original research | A structured questionnaire was distributed across expert centers in the European Reference Network CRANIO. In total, 138 surgical protocols for CP, UCLP, and BCLP were identified. | - | - | - | - | 138 different treatment protocols were identified across Europe, reflecting significant heterogeneity in practice. |

| A Descriptive Study of Chlorhexidine as a Disinfectant in Cleft Palate Surgery. [26] | 2018 | RPA | original research | Swabs were taken from the surgical site of 50 patients with cleft soft palate, before and after disinfecting and were sent for microbiological diagnostics. | 50 (25 male, 26 female patients) | Mean age 7 months | soft palate cleft | observation | Chlorhexidine significantly reduced the number of microorganisms in the surgical site of the palate. The study confirmed its effectiveness as a disinfectant. |

| Comparison of antimicrobial and wound-healing effects of silver nanoparticle and chlorhexidine mouthwashes: an in vivo study in rabbits. [27] | 2022 | Iran | original research | Microbial samples were collected from 60 rabbits, and then standardized wounds were created. After surgery, the animal models were randomly divided into 4 groups. The control group did not receive any postoperative mouthwash, 1 group received 9.80 wt% silver nanoparticle mouthwash; group 2 received all the ingredients of the formulated mouthwash except for silver nanoparticles; group 3 received chlorhexidine 2.0% mouthwash. | - | - | - | - | In rabbits, rinses with silver nanoparticles and chlorhexidine reduced bacterial colonization, and silver showed additional healing benefits. Both treatments were effective. |

| A prospective clinical evaluation of the effects of chlorhexidine, warm saline mouth washes and microbial growth on intraoral sutures. [28] | 2015 | Nigeria | original research | The study group consisted of 100 patients. They were randomly divided into 3 groups. 1 group used chlorhexidine, 2 group used warm saline, control group used warm water mouth rinses. | 100 (51 male, 49 female patients) | Range between 18 and 50 years | - | observation | The study showed that neither chlorhexidine nor warm saline mouth rinses had a meaningful impact on suture absorption time or the level of bacterial colonization on the sutures. |

| Role of Postoperative Antimicrobials in Cleft Palate Surgery: Prospective, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Study in India. [29] | 2015 | India | clinical trial | The study included 518 patients divided into two groups. The study group received 5 days of prophylactic antibiotic therapy postoperatively; the control group received a placebo. Both groups received a dose of antibiotics preoperatively. | 518 | Median 9 years old | cleft palate | observation | The rate of postoperative complications, including fistulas, was lower in the group of patients who received postoperative antibiotic therapy instead of placebo. |

| “Antibiotic Use in Primary Palatoplasty: A Survey of Practice Patterns, Assessment of Efficacy, and Proposed Guidelines for Use.” [9] | 2016 | USA | survey study + retrospective study | A survey was administered to surgeons (out of 1115, only 312 responded). Retrospective study group consisted of 311 patients who had undergone palatoplasty surgery. Two groups were studied. Group 1 received no antibiotics. Group 2 received preoperative and/or postoperative antibiotics. | 311 patients | Mean age for group one was 3.1 years, and for group two, 2.9 years | cleft palate | observation | The study showed no significant differences between the groups in the incidence of fistulas and delayed healing. 85% of surgeons administered prophylactic perioperative antibiotic therapy, but there is no consensus on the length or type of antibiotic therapy used. Considering the possible complications that may occur, the researchers recommend a single preoperative dose of antibiotic. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Budner, M.; Podleśna, M.; Domańska, A.; Pijas, N.; Zyska, K.; Wiśniewski, D.; Garbacki, K.; Wilhelm, G.; Torres, K.; Strużyna, J.; et al. Prophylactic Antibiotic Therapy in Cleft Surgery—A Scoping Review. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010056

Budner M, Podleśna M, Domańska A, Pijas N, Zyska K, Wiśniewski D, Garbacki K, Wilhelm G, Torres K, Strużyna J, et al. Prophylactic Antibiotic Therapy in Cleft Surgery—A Scoping Review. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleBudner, Margareta, Marcelina Podleśna, Aleksandra Domańska, Natalia Pijas, Katarzyna Zyska, Daniel Wiśniewski, Klaudiusz Garbacki, Grzegorz Wilhelm, Kamil Torres, Jerzy Strużyna, and et al. 2026. "Prophylactic Antibiotic Therapy in Cleft Surgery—A Scoping Review" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010056

APA StyleBudner, M., Podleśna, M., Domańska, A., Pijas, N., Zyska, K., Wiśniewski, D., Garbacki, K., Wilhelm, G., Torres, K., Strużyna, J., & Surowiecka, A. (2026). Prophylactic Antibiotic Therapy in Cleft Surgery—A Scoping Review. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010056