Palmitic Acid Induces Inflammatory Environment and Is Involved in Pyroptosis in a Human Dental Pulp Cell Line

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

2.4. Cell Morphology

2.5. Quantitative Reverse-Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

2.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

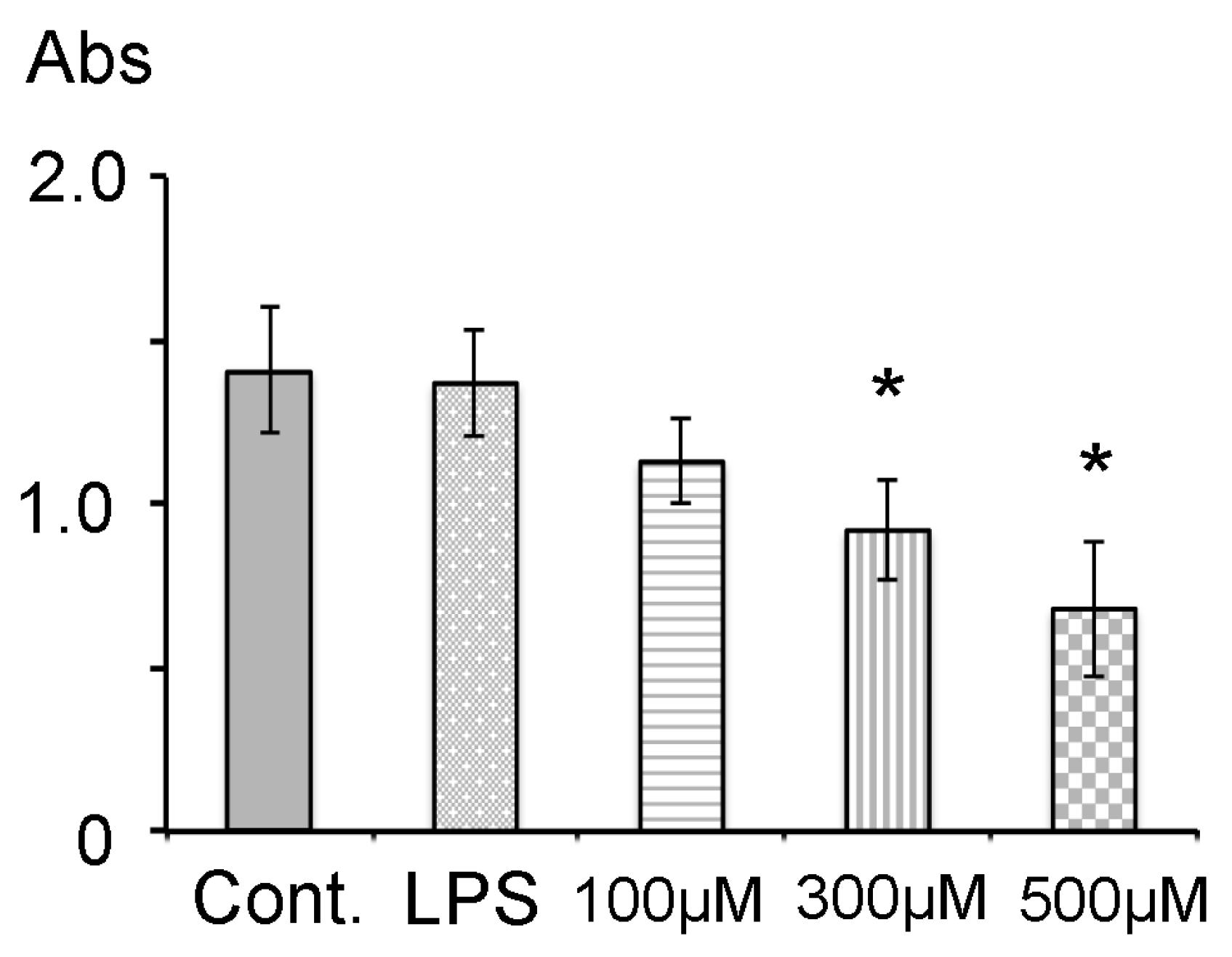

3.1. Cell Viability

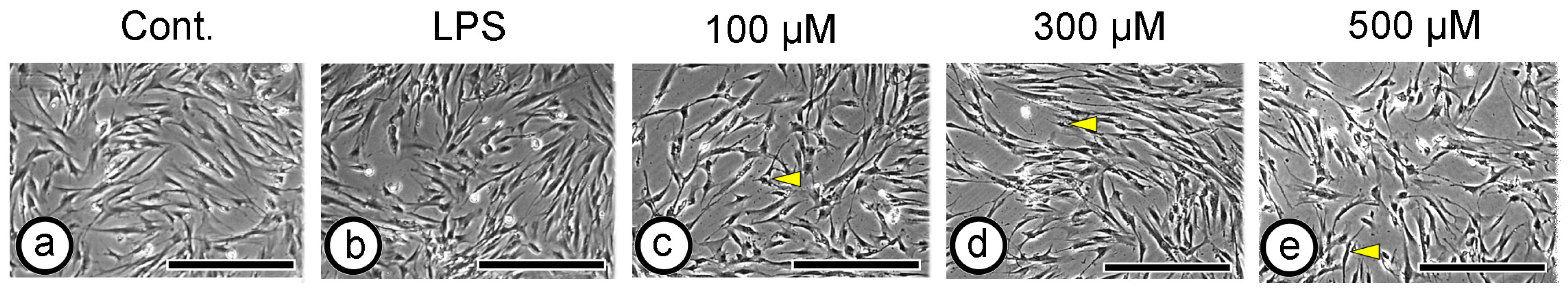

3.2. Cell Morphology

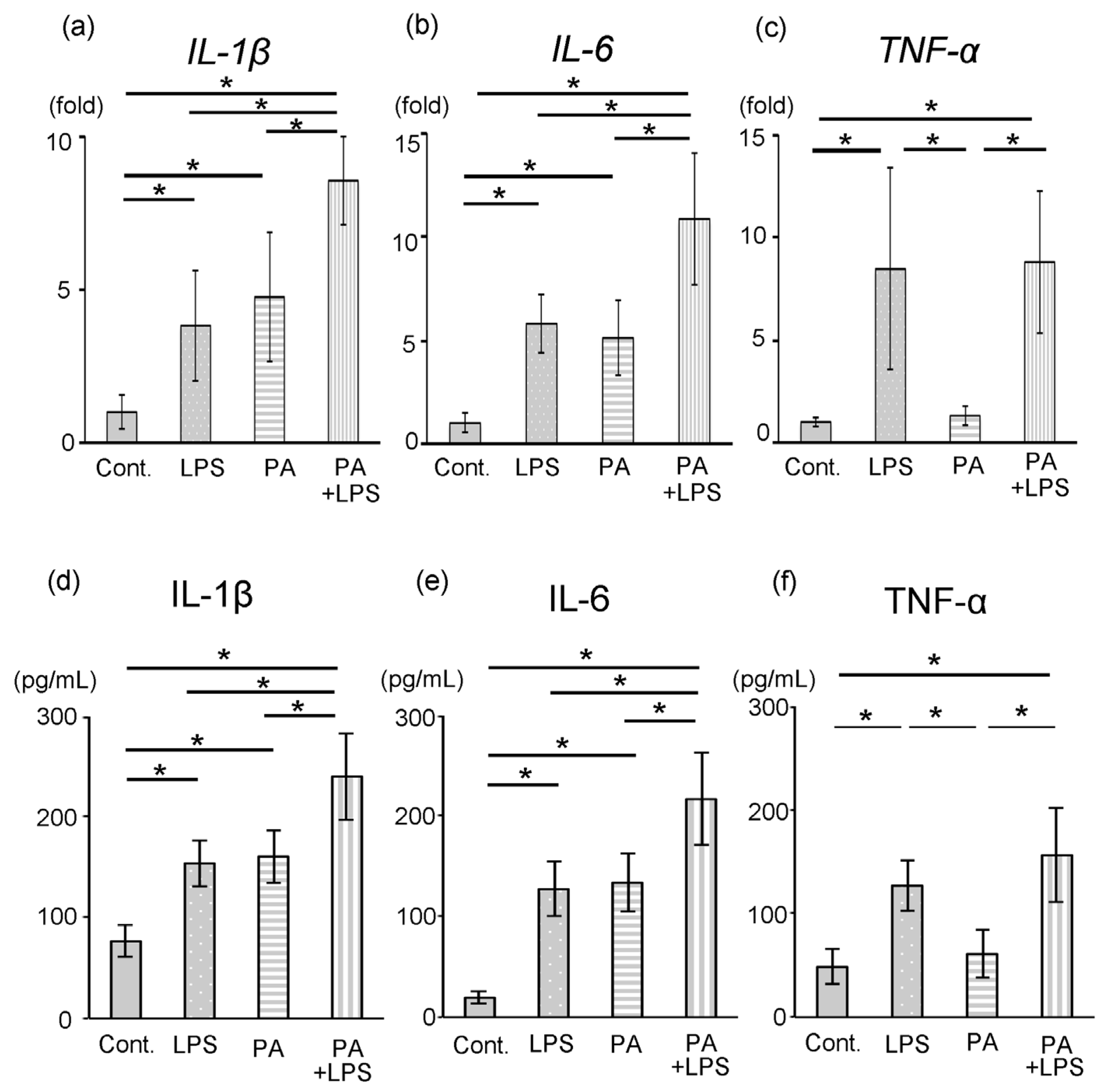

3.3. Expression of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α

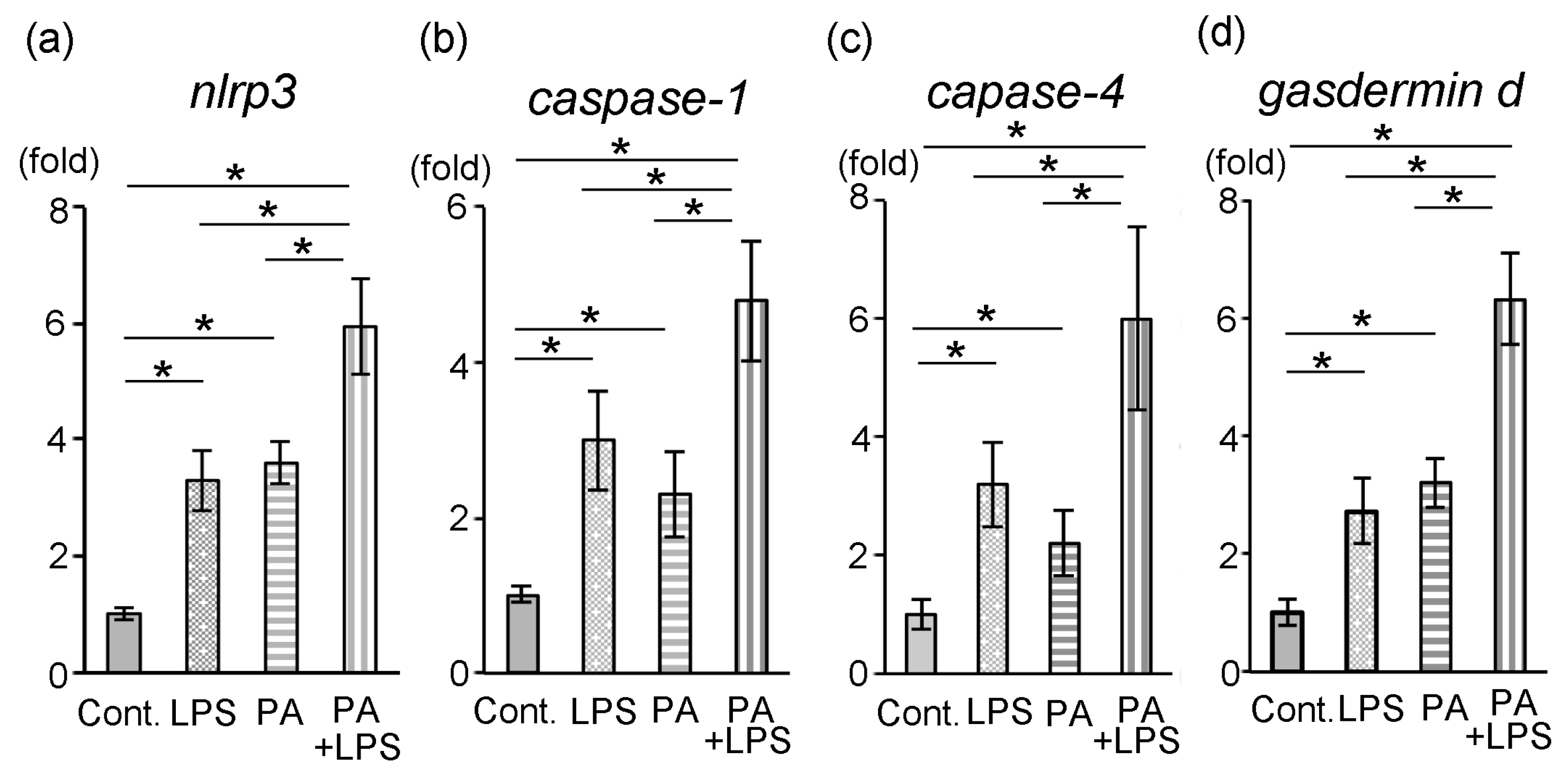

3.4. Expression of nlrp3, Caspase-1, Caspase-4 and Gasdermin d

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Palmitic acid |

| FFA | Free fatty acid |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MEM | Minimum essential medium |

| HDP | Human dental pulp cell |

References

- Li, X.; Kolltveit, K.M.; Tronstad, L.; Olsen, I. Systemic diseases caused by oral infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.D.; Papapanou, P.N.; Philips, K.H.; Offenbacher, S. Periodontal Medicine: 100 years of progress. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.G.; Shlossman, M.; Budding, L.M.; Pettitt, D.J.; Saad, M.F.; Genco, R.J.; Knowler, W.C. Periodontal disease and NIDDM in Pima Indians. Diabetes Care 1990, 13, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Shimazaki, Y. Obesity and periodontitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 482–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalla, E.; Papapanou, P.N. Diabetes mellitus and periodontitis: A tale of two common interrelated diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2011, 7, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.G. The dental pulp in diabetes mellitus. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1967, 70, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissada, N.F.; Sharaway, A.M. Histological study of gingival and pulpal vascular changes in human diabetics. Egypt. Dent. J. 1970, 16, 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, I.B.; Seltzer, S.; Freedland, J.B. The relationship of systemic disease to endodontic failures and treatment procedures. Oral Surg. 1963, 16, 1102–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, G. Role of fatty acids in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in NIDDM. Diabetes 1997, 46, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, J.D. Banting lecture 2001: Dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism in the etiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2002, 51, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagni, J.; de Macedo, I.C.; Gaio, E.J.; Souza, A.; de Molon, R.S.; Cirelli, J.A.; Hoefel, A.L.; Kucharski, L.C.; Torres, I.L.; Rösing, C.K. Obesity and hyperlipidemia modulate alveolar bone loss in Wistar rats. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, e9–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kırzıoğlu, F.Y.; Fentoğlu, Ö.; Bulut, M.T.; Doğan, B.; Özdem, M.; Özmen, Ö.; Çarsancaklı, S.A.; Ergün, A.G.; Orhan, H. Is a cholesterol-enriched diet a risk factor for alveolar bone loss? J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Ji, Q.; Sun, W.; Hong, R.; Xu, Q. An experimental hyperlipidemia model with periodontitis in mice. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jawahar, G.; Rao, G.N.; Vennila, A.A.; Fathima, S.D.; Lawanya, M.K.K.; Doss, D.M.; Sherwood, I.A.; Antinisha, A.A.; Bhuvana, B. Clinicopathological correlation of pulp stones and its association with hypertension and hyperlipidemia: An hospital-based prevalence study. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13, S1268–S1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, P. Hyperlipidemia induced by high-fat diet enhances dentin formation and delays dentin mineralization in mouse incisor. J. Mol. Histol. 2016, 47, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, R.G.; Huang, S.; Choi, I.W.; Rutledge, J.C.; Hwang, D.H. Inflammasome-mediated secretion of IL-1β in human monocytes through TLR2 activation; modulation by dietary fatty acids. J. Immunol. 2003, 191, 4337–4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, E.; Sweet, I.R.; Hockenbery, D.M.; Pham, M.; Rizzo, N.O.; Tateya, S.; Handa, P.; Schwartz, M.W.; Kim, F. Activation of NF-kappaB by palmitate in endothelial cells: A key role for NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide in response to TLR4 activation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 1370–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murru, E.; Manca, C.; Carta, G.; Banni, S. Impact of dietary palmitic acid on lipid metabolism. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 861664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, H.E.; Toth, P.P.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Abate, M.; Aronne, L.J.; Brown, W.V.; Gonzalez-Campoy, J.M.; Jones, S.R.; Kumar, R.; La Forge, R.; et al. Obesity, adiposity, and dyslipidemia: A consensus statement from the National Lipid Association. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2013, 7, 304–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbecki, J.; Bajdak-Rusinek, K. The effect of palmitic acid on inflammatory response in macrophages: An overview of molecular mechanisms. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 68, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikama, Y.; Kudo, Y.; Ishimaru, N.; Funaki, M. Possible involvement of palmitate in pathogenesis of periodontitis. J. Cell Physiol. 2015, 230, 2981–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolova, M.; Vinge, L.E.; Alfsnes, K.; Olsen, M.B.; Eide, L.; Kaasbøll, O.J.; Attramadal, H.; Torp, M.K.; Fosshaug, L.E.; Rashidi, A.; et al. Palmitate promotes inflammatory responses and cellular senescence in cardiac fibroblasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2017, 1862, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Zhuang, Q.; Ning, M.; Wu, S.; Lu, L.; Wan, X. Palmitic acid stimulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation through TLR4-NF-κB signal pathway in hepatic stellate cells. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.J.; Chen, M.Z.; Zhang, W.H.; Zhao, B.J.; Zhang, M.H.; Han, X.X.; Yu, L.M.; Liu, Y.H. Palmitic acid induces GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis in periodontal ligament cells via the NF-kB pathway. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 2546–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.F.; Lan, Z.X.; Xin, Z.Q.; He, C.R.; Guo, Z.M.; Xia, X.B.; Hu, T. Emerging insights into molecular mechanisms underlying pyroptosis and functions of inflammasomes in diseases. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 3207–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zheng, Y.X.; Huang, Y.; Tang, D.L.; Kang, R.; Chen, R.C. The versatile Gasdermin family: Their function and roles in diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 751533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezbradica, J.S.; Coll, R.C.; Boucher, D. Activation of the non-canonical inflammasome in mouse and human cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2459, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Chan, W.; Yue, Y. A significant other: Non-canonical caspase-4/5/11 inflammasome in periodontitis. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; He, M.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Meng, W. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide affects oral epithelial connections via pyroptosis. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Hu, Y.; Hu, X.; Yang, L.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Gu, X. Ginsenoside Rb2 improves insulin resistance by inhibiting adipocyte pyroptosis. Adipocyte 2020, 9, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, M.; Ueda, H.; Iizuka, S.; Sakamoto, K.; Oka, H.; Kudo, Y.; Ogawa, I.; Miyauchi, M.; Tahara, H.; Takata, T. Immortalization and characterization of human dental pulp cells with odontoblastic differentiation. Arch. Oral Biol. 2007, 52, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muramatsu, T.; Hamano, H.; Ogami, K.; Ohta, K.; Inoue, T.; Shimono, M. Reduction of connexin 43 expression in aged human dental pulp. Int. Endod. J. 2004, 37, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muramatsu, T.; Hamano, H.; Ogami, K.; Ohta, K.; Inoue, T.; Shimono, M. Reduction of osteocalcin expression in aged human dental pulp. Int. Endod. J. 2005, 38, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiuchi, A.; Sano, Y.; Furusawa, M.; Abe, S.; Muramatsu, T. Human dental pulp cells express cellular markers for inflammation and hard tissue formation in response to bacterial information. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, D.; Wang, X.; Gurley, E.C.; Liu, R.; Li, X.; Hylemon, P.B.; Chen, W.; Zhou, H. Berberine inhibits free fatty acid and LPS-induced inflammation via modulating ER stress response in macrophages and hepatocytes. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Seo, G.; Oh, E.; Jin, S.H.; Chae, G.T.; Lee, S.B. Palmitate induces RIP1-dependent necrosis in RAW 264.7 cells. Atherosclerosis 2012, 225, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xia, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Lv, Y.; Wei, S.; Liu, J.; Quan, J. Palmitate induces VSMC apoptosis via toll like receptor (TLR)4/ROS/p53 pathway. Atherosclerosis 2017, 263, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, K.; Kaneko, Y.; Muramatsu, T.; Shimono, M.; Inoue, T. Pulp cell responses during hypoxia and reoxygenation in vitro. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2003, 111, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, T.; Yuasa, K.; Ebihara, K.; Shibukawa, Y.; Ohta, K.; Furusawa, M.; Shimono, M. Glucose-free conditions induce the expression of AMPK in dental pulp cells. Arch. Oral Biol. 2013, 58, 1603–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, T.; Muramatsu, T.; Amemiya, K.; Kubo, K.; Shimono, M. Response of rat pulp cells to heat stress in vitro. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 432–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.K.; Muramatsu, T.; Uekusa, T.; Lee, J.H.; Shimono, M. Heat stress induces ALP activity and HSP25 expression in cultured dental pulp. Int. Endod. J. 2008, 41, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhan, X.; Cui, L.; Xu, S.; Ma, D.; Yue, J.; Wu, B.; Gao, J. TLR4 activation by lipopolysaccharide and Streptococcus mutans induces differential regulation of proliferation and migration in human dental pulp stem cells. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutoh, N.; Watabe, H.; Chieda, K.; Tani-Ishii, N. Expression of Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 in inflamed pulp in severe combined immunodeficiency mice. J. Endod. 2007, 35, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.V.; Greyson, C.R.; Schwartz, G.G. PPAR-γ as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease: Evidence and uncertainty. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 1738–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, G.I.; Langley, K.G.; Berglund, N.A.; Kammoun, H.; Reibe, S.; Estevez, E.; Weir, J.; Mellett, N.A.; Pernes, G.; Conway, J.R.W.; et al. Evidence that TLR4 is not a receptor for saturated fatty acids but mediates lipid-induced inflammation by reprogramming macrophage metabolism. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1096–1110.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusho, H.; Miyauchi, M.; Hyogo, H.; Inubushi, T.; Ao, M.; Ouhara, K.; Hisatune, J.; Kurihara, H.; Sugai, M.; Hayes, C.N.; et al. Dental infection of Porphyromonas gingivalis exacerbates high fat diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.F.; Carrouel, F.; Colomb, E.; Durand, S.H.; Baudouin, C.; Msika, P.; Bleicher, F.; Vincent, C.; Staquet, M.J.; Farges, J.C. Toll-like receptor 2 activation by lipoteichoic acid induces differential production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in human odontoblasts, dental pulp fibroblasts and immature dendritic cells. Immunobiology 2010, 215, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, N.; et al. Targeting JAK2 with a multifunctional nanoinhibitor for long-lasting anti-inflammatory effects and bone repair. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Q.; Nie, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, P.; Yuan, Q.; Ji, N.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Q. Metformin ameliorates the NLPP3 inflammasome mediated pyroptosis by inhibiting the expression of NEK7 in diabetic periodontitis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2020, 116, 104763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Bai, M.; Shen, W. Reduced glutathione promotes human hepatocytes from palmitate-mediated injury by suppressing endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Hepatogastroenterology 2011, 58, 1670–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillon, N.J.; Chan, K.L.; Zhang, S.; Mejdani, M.; Jacobson, M.R.; Ducos, A.; Bilan, P.J.; Niu, W.; Klip, A. Saturated fatty acids activate caspase-4/5 in human monocytes, triggering IL-1β and IL-18 release. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 311, E825–E835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, S.M.; Narayanan, M.; Jacob, M. Insidious role of diabetes mellitus on nerves and dental pulp. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2019, 13, ZE05–ZE07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, I.B.; Bender, A.B. Diabetes mellitus and the dental pulp. J. Endod. 2003, 29, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, R.M.N.; Dos Reis-Prado, A.H.; de Castro Oliveira, S.; Goto, J.; Cosme-Silva, L.; Cintra, L.T.A.; Benetti, F. Effects of diabetes mellitus on dental pulp: A systematic review of in vivo and in vitro studies. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Muramatsu, T.; Yanagisawa, A.; Mitomo, K.; Takada, K.; Furusawa, M.; Abiko, Y.; Jung, H.-S. Palmitic Acid Induces Inflammatory Environment and Is Involved in Pyroptosis in a Human Dental Pulp Cell Line. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010051

Muramatsu T, Yanagisawa A, Mitomo K, Takada K, Furusawa M, Abiko Y, Jung H-S. Palmitic Acid Induces Inflammatory Environment and Is Involved in Pyroptosis in a Human Dental Pulp Cell Line. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuramatsu, Takashi, Akihide Yanagisawa, Keisuke Mitomo, Kana Takada, Masahiro Furusawa, Yoshihiro Abiko, and Han-Sung Jung. 2026. "Palmitic Acid Induces Inflammatory Environment and Is Involved in Pyroptosis in a Human Dental Pulp Cell Line" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010051

APA StyleMuramatsu, T., Yanagisawa, A., Mitomo, K., Takada, K., Furusawa, M., Abiko, Y., & Jung, H.-S. (2026). Palmitic Acid Induces Inflammatory Environment and Is Involved in Pyroptosis in a Human Dental Pulp Cell Line. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010051