Dens Invaginatus—Mandibular Second Molar—Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. The First Visit

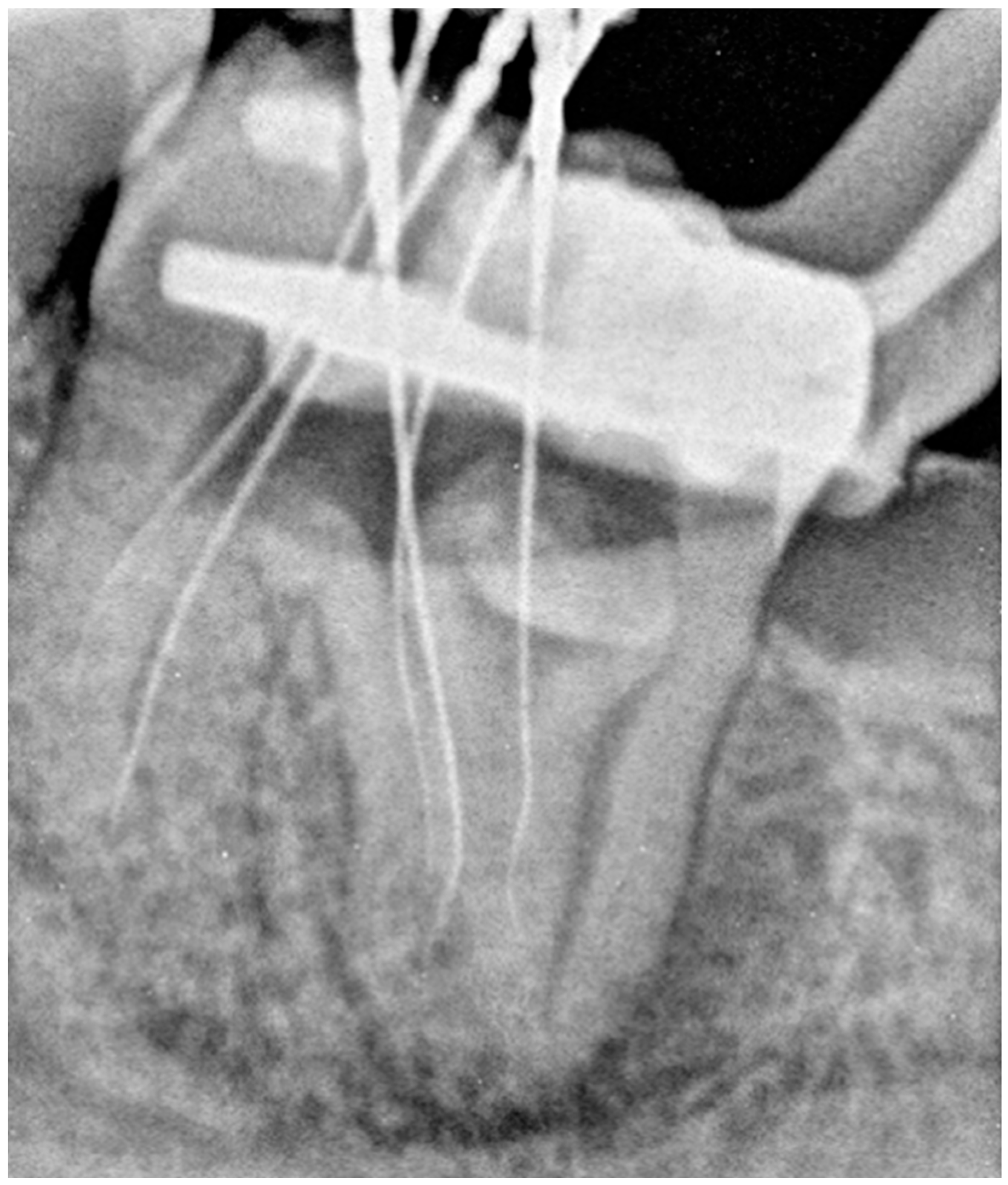

2.2. The Second Appointment

2.3. The Third Appointment

2.4. The Fourth Appointment

2.5. The Fifth Appointment

2.6. Sixth Appointment

3. Discussion

3.1. Study Limitations

3.2. Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBCT | Cone-Beam Computed Tomography |

| DI | Dens invaginatus |

| OPG | Orthopantomogram |

| RCT | Root Canal Treatment |

References

- Alani, A.; Bishop, K. Dens Invaginatus. Part 1: Classification, Prevalence and Aetiology. Int. Endod. J. 2008, 41, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Association of Endodontists. Glossary of Endodontic Terms, 10th ed.; American Association of Endodontists: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, K.; Alani, A. Dens Invaginatus. Part 2: Clinical, Radiographic Features and Management Options. Int. Endod. J. 2008, 41, 1137–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronfeld, R. Dens in Dente. J. Dent. Res. 1934, 14, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehlers, F.A.C. Dens Invaginatus (Dilated Composite Odontome). Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1957, 10, 1204–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, S.R. The Permanent Maxillary Lateral Incisor. Am. J. Orthod. Oral Surg. 1943, 29, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, C.W. Endodontic Treatment of an Immature Maxillary Lateral Incisor with Type II Dens Invaginatus in an Orthodontic Patient: A Case Report. Aust. Endod. J. 2023, 49, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memis, S.; Bas, Z. Multiple Dens Invaginatus in Wilson’s Disease: A Case Report. Aust. Endod. J. 2021, 47, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, A.; Singal, D.; Giri, K.Y.; Agarwal, A.; Keerthi, S.S. An Immature Type II Dens Invaginatus in a Mandibular Lateral Incisor with Talon’s Cusp: A Clinical Dilemma to Confront. Case Rep. Dent. 2014, 2014, 82694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokala, P.; Acs, G. A Constellation of Dental Anomalies in a Chromosomal Deletion Syndrome (7q32): Case Report. Pediatr. Dent. 1994, 16, 306–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hosey, M.-T.; Bedi, R. Multiple Dens Invaginatus in Two Brothers. Dent. Traumatol. 1996, 12, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedano, H.O.; Ocampo-Acosta, F.; Naranjo-Corona, R.I.; Torres-Arellano, M.E. Multiple Dens Invaginatus, Mulberry Molar and Conical Teeth. Case Report and Genetic Considerations. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2009, 14, E69–E72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Von den Hoff, J.; Meng, L. An Update on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dens Invaginatus. Aust. Dent. J. 2017, 62, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunduz, K.; Celenk, P.; Canger, E.; Zengin, Z.; Sumer, P. A Retrospective Study of the Prevalence and Characteristics of Dens Invaginatus in a Sample of the Turkish Population. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2013, 18, e27–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, J.F.; Rôças, I.N.; Hernández, S.R.; Brisson-Suárez, K.; Baasch, A.C.; Pérez, A.R.; Alves, F.R.F. Dens Invaginatus: Clinical Implications and Antimicrobial Endodontic Treatment Considerations. J. Endod. 2022, 48, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różyło, T.K.; Różyło-Kalinowska, I.; Piskórz, M. Cone-Beam Computed Tomography for Assessment of Dens Invaginatus in the Polish Population. Oral Radiol. 2018, 34, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, H. Investigation of Dens Invaginatus in a Chinese Subpopulation Using Cone-beam Computed Tomography. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 1755–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves dos Santos, G.N.; Sousa-Neto, M.D.; Assis, H.C.; Lopes-Olhê, F.C.; Faria-e-Silva, A.L.; Oliveira, M.L.; Mazzi-Chaves, J.F.; Candemil, A.P. Prevalence and Morphological Analysis of Dens Invaginatus in Anterior Teeth Using Cone Beam Computed Tomography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2023, 151, 105715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mancilla, S.; Montero-Miralles, P.; Saúco-Márquez, J.; Areal-Quecuty, V.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Segura-Egea, J. Prevalence of Dens Invaginatus Assessed by CBCT: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2022, 14, e959–e966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mupparapu, M.; Singer, S.R. A Review of Dens Invaginatus (Dens in Dente) in Permanent and Primary Teeth: Report of a Case in a Microdontic Maxillary Lateral Incisor. Quintessence Int. 2006, 37, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Rubio, A.; Segura, J.J.; Jiménez-Planas, A.; Llamas, R. Multiple Dens Invaginatus Affecting Maxillary Lateral Incisors and a Supernumerary Tooth. Dent. Traumatol. 1997, 13, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagińska, J.; Rodakowska, E.; Piszczatowski, S.; Kierklo, A.; Duraj, E.; Konstantynowicz, J. Dens Invagination and Root Dilaceration in Double Multilobed Mesiodentes in 14-Year-Old Patient with Anorexia Nervosa. Folia Morphol. 2017, 76, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, E.A. Multiple Dental Anomalies in a Young Patient: A Case Report. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2000, 10, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durack, C.; Patel, S. The Use of Cone Beam Computed Tomography in the Management of Dens Invaginatus Affecting a Strategic Tooth in a Patient Affected by Hypodontia: A Case Report. Int. Endod. J. 2011, 44, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, R. Endodontic Management of a Mandibular Incisor Exhibiting Concurrence of Fusion, Talon Cusp and Dens Invaginatus Using CBCT as a Diagnostic Aid. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, ZD01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colak, H.; Yilmaz, C.; Keklik, H.; Colak, T. Talon Cusps Occurring Concurrently with Dens Invaginatus on a Permanent Maxillary Lateral Incisor: A Case Report and Literature Review. Gen. Dent. 2014, 62, e14–e18. [Google Scholar]

- Pandiar, D. Light Microscopic Features of Type II Dens Invaginatus in A Deciduous Mandibular Molar. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZJ03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, S.; Padmashree, S.; Nimbale, A. Dens Invagination: A Review of Literature and Report of Two Cases. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2016, 8, 901–905. [Google Scholar]

- Fregnani, E.R.; Spinola, L.F.B.; Sônego, J.R.O.; Bueno, C.E.S.; De Martin, A.S. Complex Endodontic Treatment of an Immature Type III Dens Invaginatus. A Case Report. Int. Endod. J. 2008, 41, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Wang, D.; Shen, L.; Lu, P.; Meng, Z.; Zhou, R. Treatment Opinions for Dens Invaginatus: A Case Series. Exp. Ther. Med. 2024, 27, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruwa, A.O.; Anderson, C.; Monroe, A.; Cracel Nogueira, F.; Corte-Real, L.; Martins, J.N.R. Dens Invaginatus: A Comprehensive Review of Classification and Clinical Approaches. Medicina 2025, 61, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichota, D.; Lipski, M.; Woźniak, K.; Buczkowska-Radlińska, J. Endodontic Treatment of a Maxillary Canine with Type 3 Dens Invaginatus and Large Periradicular Lesion: A Case Report. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Niu, C.; Zhang, P.; Ran, S.; Huang, Z. Endodontic Management Considerations for Type III Dens Invaginatus Based on Anatomical Characteristics: A Case Series. Aust. Endod. J. 2024, 50, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mupparapu, M.; Singer, S. A Rare Presentation of Dens Invaginatus in a Mandibular Lateral Incisor Occurring Concurrently with Bilateral Maxillary Dens Invaginatus: Case Report and Review of Literature. Aust. Dent. J. 2004, 49, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Wei, X. Combined Therapy for a Rare Case of Type III Dens Invaginatus in a Mandibular Central Incisor with a Periapical Lesion: A Case Report. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 1378–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Wu, Z.; Tu, Y. Treatment of Type III Dens Invaginatus in Bilateral Immature Mandibular Central Incisors: A Case Report. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricucci, D.; Milovidova, I.; Siqueira, J.F. Unusual Location of Dens Invaginatus Causing a Difficult-to-Diagnose Pulpal Involvement. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1522–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nino-Barrera, J.; Alzate-Mendoza, D.; Olaya-Abril, C.; Gamboa-Martinez, L.F.; Guamán-Laverde, M.; Lagos-Rosero, N.; Romero-Diaz, A.C.; Duran, N.; Vanegas-Hoyose, L. Atypical Radicular Anatomy in Permanent Human Teeth: A Systematic Review. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 50, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Baz, P.; Gancedo-Gancedo, T.; Pereira-Lores, P.; Mosquera-Barreiro, C.; Martín-Biedma, B.; Faus-Matoses, V.; Ruíz-Piñón, M. Conservative Management of Dens in Dente. Aust. Endod. J. 2023, 49, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancino, D.; Abdellatif, D.; Iandolo, A.; Bornert, F.; Haïkel, Y. An Unusual Case of Dens Invaginatus on a Mandibular Second Molar: A Case Report. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2025, 50, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, S.; Chen, X.; Jia, X. CBCT Analysis of the Incidence of Maxillary Lateral Incisor Dens Invaginatus and Its Impact on Periodontal Supporting Tissues. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löst, C. Quality Guidelines for Endodontic Treatment: Consensus Report of the European Society of Endodontology. Int. Endod. J. 2006, 39, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P.V. Present Status and Future Directions: Managing Endodontic Emergencies. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 778–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naoum, H.J.; Chandler, N.P. Temporization for Endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2002, 35, 964–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, R.C.; Fensterseifer, M.; Peters, O.A.; de Figueiredo, J.A.P.; Gomes, M.S.; Rossi-Fedele, G. Methods for Measurement of Root Canal Curvature: A Systematic and Critical Review. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vertucci, F.J. Root Canal Anatomy of the Human Permanent Teeth. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1984, 58, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. The Use of Cone Beam Computed Tomography in the Conservative Management of Dens Invaginatus: A Case Report. Int. Endod. J. 2010, 43, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasz-Kaczmarek, A.; Surdacka, A. Cone Beam Computed Tomography Imaging in Clinical Endodontics—Literature Review. Dent. Med. Probl. 2013, 50, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, H. Non-Surgical Endodontic Treatment for Dens Invaginatus Type III Using Cone Beam Computed Tomography and Dental Operating Microscope: A Case Report. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 2013, 54, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharangate, N.; Figueiredo, N.; Fernandes, M.; Lambor, R. Bilateral Dens Invaginatus in the Mandibular Premolars—Diagnosis and Treatment. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2015, 6, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, M.; Adnan, S.; Umer, F. A Variant of the Current Dens Invaginatus Classification. Front. Dent. 2020, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Durack, C.; Abella, F.; Roig, M.; Shemesh, H.; Lambrechts, P.; Lemberg, K. European Society of Endodontology Position Statement: The Use of CBCT in Endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2014, 47, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, N.; Li, W.-L.; Zheng, X.-Y.; Li, S. Management of Type IIIb Dens Invaginatus Using a Combination of Root Canal Treatment, Intentional Replantation, and Surgical Therapy: A Case Report. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 6261–6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spallarossa, M.; Canevello, C.; Silvestrini Biavati, F.; Laffi, N. Surgical Orthodontic Treatment of an Impacted Canine in the Presence of Dens Invaginatus and Follicular Cyst. Case Rep. Dent. 2014, 2014, 643082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabrouk, R.; Berrezouga, L.; Frih, N. The Accuracy of CBCT in the Detection of Dens Invaginatus in a Tunisian Population. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 8826204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abella Sans, F.; Garcia-Font, M.; Suresh, N.; Dummer, P.M.H.; Nagendrababu, V. Guided Intentional Replantation of a Mandibular Premolar with Type IIIb Dens Invaginatus Associated with Peri-Invagination Periodontitis without Root Canal Treatment: A Case Report. J. Endod. 2024, 51, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P.K.; Wankhade, J.; Warhadpande, M. A Rare Case of Type III Dens Invaginatus in a Mandibular Second Premolar and Its Nonsurgical Endodontic Management by Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography: A Case Report. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Dasukil, S.; Namdev Sable, M.; Routray, S. Radicular Variant of Dens in Dente (RDinD) in a Patient Undergoing Radioisotope Therapy. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2022, 17, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaLonde, L.; Askar, M.; Paurazas, S. A Novel Diagnostic and Treatment Approach to an Unusual Case of Dens Invaginatus in a Mandibular Lateral Incisor Using CBCT and 3D Printing Technology. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Kawanishi, Y.; Okamoto, M.; Hayashi, M. Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatment of an Oehlers Type IIIa Maxillary Central Incisor with Dens Invaginatus: A Case Report. Front. Dent. Med. 2024, 5, 1458215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arow, Q.; Rosen, E.; Sela, G.; Elbahary, S.; Tsesis, I. Fifty-Year Follow-up of Dens Invaginatus Treated by Nonsurgical and Surgical Endodontic Treatments: A Case Report. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2025, 50, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabanik, P.; Samiei, M.; Avval, S.T.; Cavalcanti, B. Guided Endodontics in Managing Root Canal Treatment for Anomalous Teeth—A Narrative Review. Aust. Endod. J. 2025, 51, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayama, M.T.; Valentim, D.; Gomes-Filho, J.E.; Cintra, L.T.A.; Dezan, E. 18-Year Follow-up of Dens Invaginatus: Retrograde Endodontic Treatment. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 1688–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallacher, A.; Ali, R.; Bhakta, S. Dens Invaginatus: Diagnosis and Management Strategies. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 221, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathorn, C.; Parashos, P. Contemporary Treatment of Class II Dens Invaginatus. Int. Endod. J. 2007, 40, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwanski, M.; Pietrzycka, K.; Eyüboğlu, T.F.; Özcan, M.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M. Clinical Outcome of Non-Surgical Root Canal Treatment Using Different Sealers and Techniques of Obturation in 237 Patients: A Retrospective Study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontoriero, D.I.K.; Ferrari Cagidiaco, E.; Maccagnola, V.; Manfredini, D.; Ferrari, M. Outcomes of Endodontic-Treated Teeth Obturated with Bioceramic Sealers in Combination with Warm Gutta-Percha Obturation Techniques: A Prospective Clinical Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pietrzycka, K.; Lutomska, N.; Pameijer, C.H.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M. Dens Invaginatus—Mandibular Second Molar—Case Report. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010027

Pietrzycka K, Lutomska N, Pameijer CH, Lukomska-Szymanska M. Dens Invaginatus—Mandibular Second Molar—Case Report. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010027

Chicago/Turabian StylePietrzycka, Krystyna, Natalia Lutomska, Cornelis H. Pameijer, and Monika Lukomska-Szymanska. 2026. "Dens Invaginatus—Mandibular Second Molar—Case Report" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010027

APA StylePietrzycka, K., Lutomska, N., Pameijer, C. H., & Lukomska-Szymanska, M. (2026). Dens Invaginatus—Mandibular Second Molar—Case Report. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010027