New Digital Workflow for the Use of a Modified Stimulating Palatal Plate in Infants with Down Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

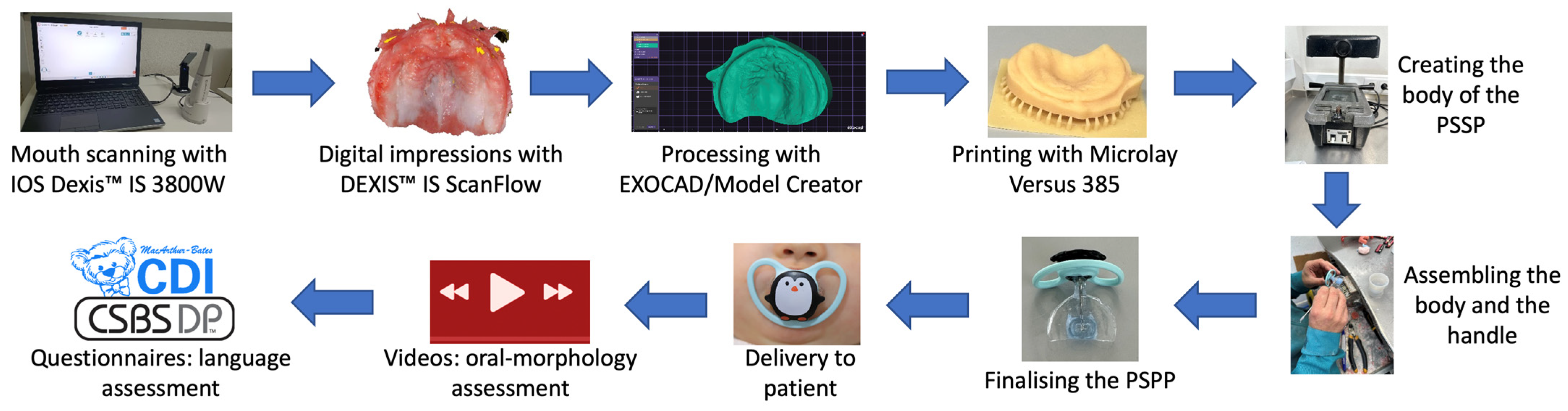

2. Materials and Methods

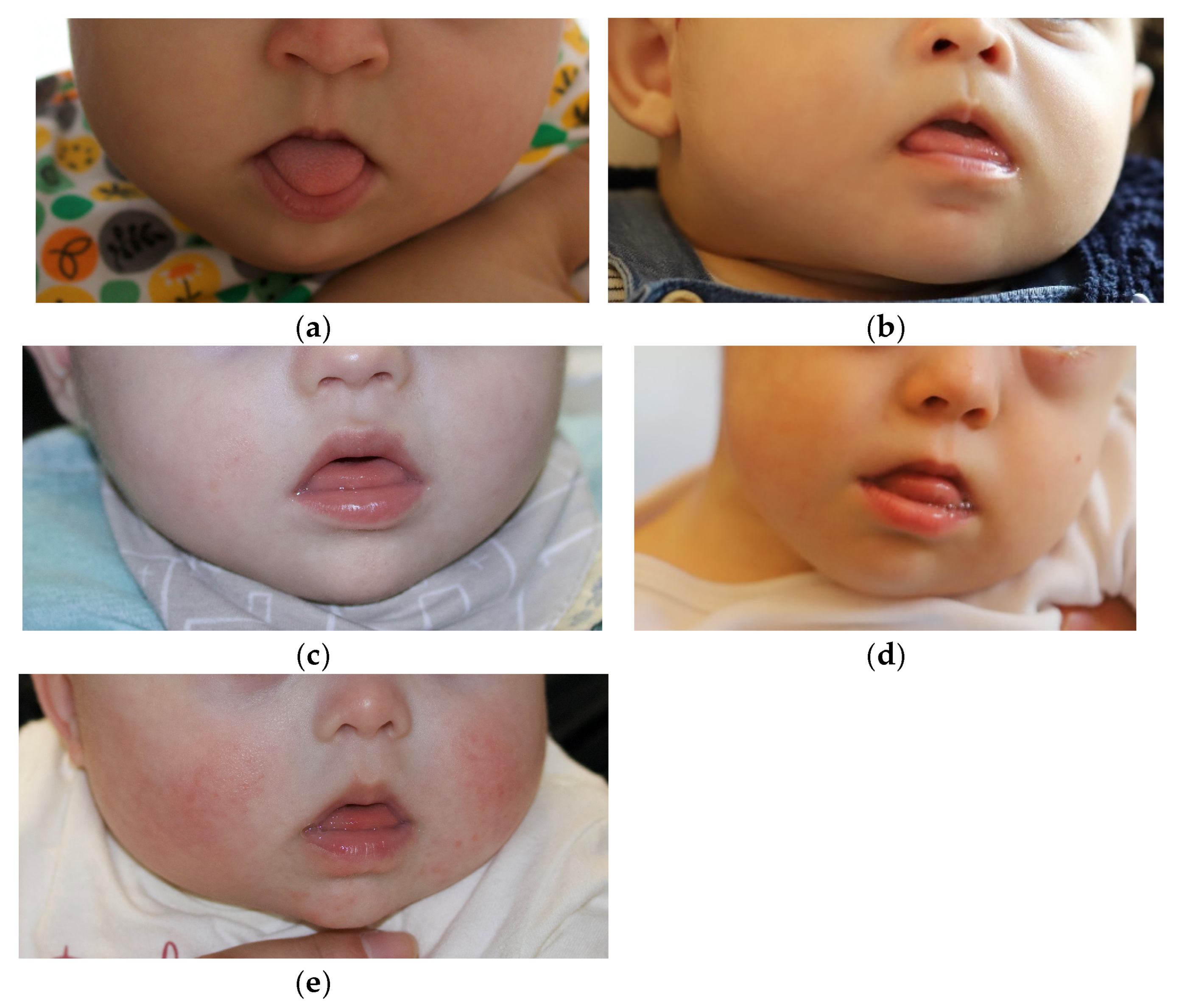

2.1. The Clinical Cases

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

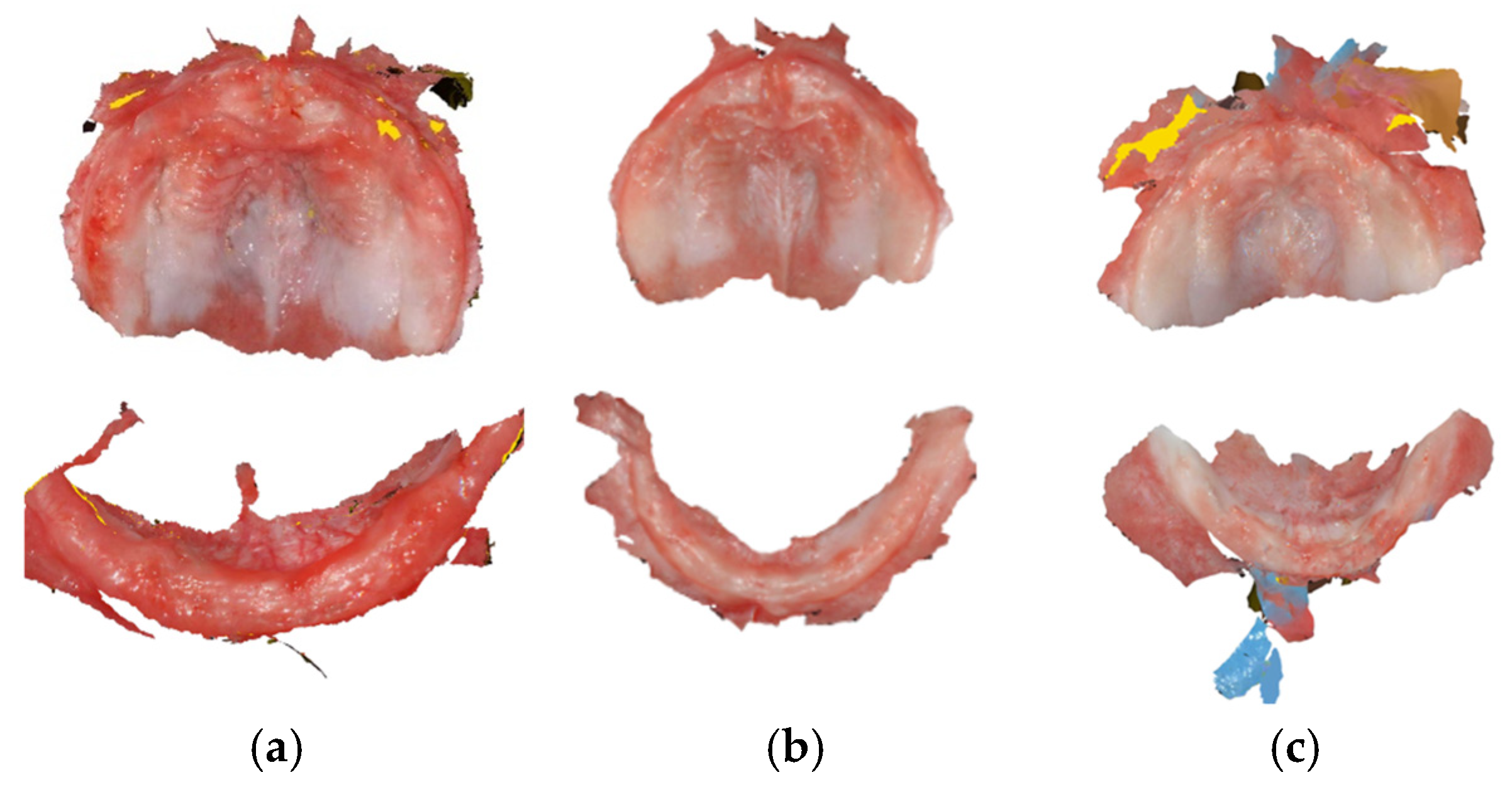

2.3.1. Mouth Scanning and Model Printing

2.3.2. Manufacturing and Delivery of the PSPP

2.3.3. Assessment of Oral-Morphological Features, Language Abilities, and Acceptability of the PSPP

2.3.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Mouth Scanning: Viability and Acceptability

3.2. From Mouth Scanning to Delivery of the PSPP

3.3. Acceptability of the PSPP by Infants and Parents

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DS | Down Syndrome |

| SPP | Stimulating palatal plate |

| PSPP | Pacifier stimulating palatal plate |

Appendix A

| Participants | Delivery Session | Successful Follow-Up Contacts | Successful Video Sessions | Parents’ Reaction/Feedback to PSPP Use | Parents’ Response to CSBS | Parents’ Response to CDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Immediate mouth closure and tongue inside the mouth. Initially tried to remove the PSPP, inducing vomiting. | 10 | 9 | Very positive. Parents requested a second PSPP. | 4 | 4 |

| Participant 2 | Immediate mouth closure and tongue inside the mouth. Initial adaptation difficult. Induced vomiting. Parents apprehensive. | 8 | 4 | Parents wanted to stop PSPP use after 6 months. | 5 | 5 |

| Participant 3 | Immediate mouth closure and tongue inside the mouth. PSPP well adapted and accepted. | 10 | 5 | Very positive. | 3 | 7 |

| Participant 4 | Immediate mouth closure and tongue inside the mouth. PSPP well adapted and accepted. An adhesive was used for fixation. | 12 | 7 | Very positive. Parents requested a second PSPP. | 4 | 8 |

| Participant 5 | Immediate mouth closure and tongue inside the mouth. PSPP well adapted and accepted. Initially, increased saliva and gagging. | 7 | 6 | Very positive. | 3 | 3 |

References

- Macho, V.; Coelho, A.; Areias, C.; Macedo, P.; Andrade, D. Craniofacial Features and Specific Oral Characteristics of Down Syndrome Children. Oral Health Dent. Manag. 2014, 13, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sperling, K.; Scherb, H.; Neitzel, H. Population Monitoring of Trisomy 21: Problems and Approaches. Mol. Cytogenet. 2023, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, C.J. The Consequences of Chromosome Imbalance. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1990, 37, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhan, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, L. Global, Regional, and National Burden and Trends of Down Syndrome From 1990 to 2019. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 908482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, C.T.; Isenburg, J.L.; Canfield, M.A.; Meyer, R.E.; Correa, A.; Alverson, C.J.; Lupo, P.J.; Riehle-Colarusso, T.; Cho, S.J.; Aggarwal, D.; et al. National Population-Based Estimates for Major Birth Defects, 2010–2014. Birth Defects Res. 2019, 111, 1420–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Births with Down’s Syndrome per 100,000 Live Births. Available online: https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hfa_603-7120-births-with-downs-syndrome-per-100-000-live-births/#id=21649 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Díaz-Quevedo, A.A.; Castillo-Quispe, H.M.L.; Atoche-Socola, K.J.; Arriola-Guillén, L.E. Evaluation of the Craniofacial and Oral Characteristics of Individuals with Down Syndrome: A Review of the Literature. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 122, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, R.M.M.M.; Almeida, T.D.D.; Pretti, H. Effects of Using the Stimulating Palatal Plate in Combination with Orofacial Stimulation on the Habitual Tongue and Lip Posture in Children with Trisomy 21: An Integrative Literature Review. Rev. CEFAC 2022, 24, e7021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, N.; Kaczorowski, K.; Laskowska, J.; Mikulewicz, M. Down Syndrome as a Cause of Abnormalities in the Craniofacial Region: A Systematic Literature Review. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2019, 28, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.; Hedge, S.; Naik, S.; Shetty, P. Malocclusion in Down Syndrome—A Review. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2015, 70, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, E.F.; Roberts, J.; Mirrett, P.; Sideris, J.; Misenheimer, J. A Comparison of Oral Structure and Oral-Motor Function in Young Males with Fragile X Syndrome and Down Syndrome. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2006, 49, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbeduto, L.; Warren, S.F.; Conners, F.A. Language Development in Down Syndrome: From the Prelinguistic Period to the Acquisition of Literacy. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, R.D.; Eichhorn, J.; Wilson, E.M.; Suk, Y.; Bolt, D.M.; Vorperian, H.K. Auditory-Perceptual Features of Speech in Children and Adults with Down Syndrome: A Speech Profile Analysis. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2021, 64, 1157–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strome, S.E.; Strome, M. Down Syndrome: An Otolaryngologic Perspective. J. Otolaryngol. 1992, 21, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.; Yeung, H.H.; Werker, J.F. Sensorimotor Foundations of Speech Perception in Infancy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2023, 27, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Morales, R.; Brondo, J.; Høyer, H.; Limbrock, G.J. Treatment of Chewing, Swallowing and Speech Defects in Handicapped Children with Castillo-Morales Orofacial Regulator Therapy: Advice for Pediatricians and Dentists. Zahnarztl. Mitteilungen 1985, 75, 935–942. [Google Scholar]

- Limbrock, G.J.; Castillo-Morales, R.; Hoyer, H.; Stöver, B.; Onufer, C.N. The Castillo-Morales Approach to Orofacial Pathology in Down Syndrome. Int. J. Orofac. Myol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Orofac. Myol. 1993, 19, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlstedt, K.; Henningsson, G.; McAllister, A.; Dahllöf, G. Long-Term Effects of Palatal Plate Therapy on Oral Motor Function in Children with Down Syndrome Evaluated by Video Registration. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2001, 59, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Ferreira, J.E.; de Almeida, B.R.S.; Deps, T.D.; Pretti, H.; Furlan, R.M.M.M. Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy Associated with the Use of the Stimulating Palatal Plate in Children with Trisomy 21: Case Studies. CoDAS 2023, 35, e20210231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlstedt, K.; Henningsson, G.; Dahllöf, G. A Four-Year Longitudinal Study of Palatal Plate Therapy in Children with Down Syndrome: Effects on Oral Motor Function, Articulation and Communication Preferences. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2003, 61, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, D.J.C. Trissomia 21–Estudo Dento-Maxilo-Facial. Doctoral Dissertation, School of Dentistry—University of Oporto, Porto, Portugal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade, D.J.C. Placa Palatina Modificada Sob a Forma de Chupeta. Instituto Nacional de Propriedade Industrial, 2004. Available online: https://servicosonline.inpi.justica.gov.pt/pesquisas/GetSintesePDF?nord=365335 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Chate, R.A.C. A Report on the Hazards Encountered When Taking Neonatal Cleft Palatal Impressions (1983–1992). Br. J. Orthod. 1995, 22, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.; Prakash, N.; Galagali, G.; Reddy, E.S.; Devasya, A.; Nidawani, M. Oral Molding Plates a Boon to Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate Patients: A Series of Case Reports and Review. Int. J. Prev. Clin. Dent. Res. 2014, 1, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, T.; Kawanabe, H.; Fukui, K. Comparison of Conventional Impression Making and Intraoral Scanning for the Study of Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate. Congenit. Anom. 2023, 63, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weise, C.; Frank, K.; Wiechers, C.; Weise, H.; Reinert, S.; Koos, B.; Xepapadeas, A.B. Intraoral Scanning of Neonates and Infants with Craniofacial Disorders: Feasibility, Scanning Duration, and Clinical Experience. Eur. J. Orthod. 2022, 44, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limbrock, G.J.; Fischer-Brandies, H.; Avalle, C. Castillo-Morales’ Orofacial Therapy: Treatment of 67 Children with Down Syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1991, 33, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, M.G.; Severino, C.; Vigário, M.; Frota, S. Adaptation and Validation of the European Portuguese Communication and Symbolic Behaviour Scales Developmental ProfileTM (CSBS DPTM) Infant-Toddler Checklist. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2024, 59, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frota, S.; Butler, J.; Correia, S.; Severino, C.; Vicente, S.; Vigário, M. Infant Communicative Development Assessed with the European Portuguese MacArthur–Bates Communicative Development Inventories Short Forms. First Lang. 2016, 36, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, F.; Akram, Z.; Barillas, A.P.; Kellesarian, S.V.; Ahmed, H.B.; Khan, J.; Almas, K. Outcome of Orthodontic Palatal Plate Therapy for Orofacial Dysfunction in Children with Down Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2018, 21, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheets, K.B.; Best, R.G.; Brasington, C.K.; Will, M.C. Balanced Information about Down Syndrome: What Is Essential? Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2011, 155, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, B.R.S.; de Ferreira, J.E.A.; Almeida, T.D.D.; Pretti, H.; Furlan, R.M.M.M. Influência da idade e do tempo de uso da Placa Palatina de Memória por crianças com Trissomia do 21 nas mudanças miofuncionais orofaciais percebidas pelos pais, na adaptação e satisfação da família após quatro meses de tratamento. Distúrbios Comun. 2023, 35, e55472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalabothu, P.; Benitez, B.K.; de Macedo Santos, J.W.; Mueller, A.A. Cleft Lip and Palate Digital Impression Workflow. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2025, 13, e6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, N.F.R.; Warol, F.; Lima, P.; Amaral, L.D.; Dos Reis, D.B.; Picciani, B.L.S. Technical Note of a 3D Printed Stimulating Palatal Plate Prototype for Children with Trisomy 21. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2025, 17, e136–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xepapadeas, A.B.; Weise, C.; Frank, K.; Spintzyk, S.; Poets, C.F.; Wiechers, C.; Arand, J.; Koos, B. Technical Note on Introducing a Digital Workflow for Newborns with Craniofacial Anomalies Based on Intraoral Scans—Part I: 3D Printed and Milled Palatal Stimulation Plate for Trisomy 21. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, R.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Qiu, P.; Xu, H.; Cao, Y. Accuracy of Intraoral Scanning versus Conventional Impressions for Partial Edentulous Patients with Maxillary Defects. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burhardt, L.; Livas, C.; Kerdijk, W.; van der Meer, W.J.; Ren, Y. Treatment Comfort, Time Perception, and Preference for Conventional and Digital Impression Techniques: A Comparative Study in Young Patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 150, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Texier, L.; Nicolas, E.; Batisse, C. Evaluation and Comparison of the Accuracy of Three Intraoral Scanners for Replicating a Complete Denture. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 706.e1–706.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 5725-1:2023(En); Accuracy (Trueness and Precision) of Measurement Methods and Results—Part 1: General Principles and Definitions. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:5725:-1:ed-2:v1:en (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Benitez, B.K.; Brudnicki, A.; Surowiec, Z.; Wieprzowski, Ł.; Rasadurai, A.; Nalabothu, P.; Lill, Y.; Mueller, A.A. Digital Impressions from Newborns to Preschoolers with Cleft Lip and Palate: A Two-Centers Experience. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2022, 75, 4233–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weismann, C.; Xepapadeas, A.B.; Bockstedte, M.; Koos, B.; Krimmel, M.; Poets, C.F.; Aretxabaleta, M. Complete Digital Workflow for Manufacturing Presurgical Orthodontic Palatal Plates in Newborns and Infants with Cleft Lip and/or Palate. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, P.K. Infant Speech Perception. In Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 113–158. ISBN 978-1-119-68452-7. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, M.; Kamnoedboon, P.; McKenna, G.; Angst, L.; Schimmel, M.; Özcan, M.; Müller, F. CAD-CAM Removable Complete Dentures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Trueness of Fit, Biocompatibility, Mechanical Properties, Surface Characteristics, Color Stability, Time-Cost Analysis, Clinical and Patient-Reported Outcomes. J. Dent. 2021, 113, 103777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akıncı, O.; Oğuz, E.; Bozkurt, P.; Kadıoglu, M.; Ocak, M.; Orhan, K.; Kisnisci, R. Effect of Cleft Palate Type and Manufacturing Method on Feeding Plate Adaptation: A Volumetric Micro-Computed Tomography Analysis. J. Prosthodont. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Mouth Scanning Duration (Min) | Time Interval Scanning to Delivery (Days) | Total Duration of Use (Months) | Frequency of Use (Per Day) | Parental Rate Response to Follow-Up Contacts (Telephone and Video) | Parental Rate Response to Video Sessions | Parental Rate Response to CSBS | Parental Rate Response to CDI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Jaw | Lower Jaw | Total | ||||||||

| Participant 1 | 11 | 3 | 14 | 24 | 11 | 5 min to 1 h | 91% | 82% | 100% | 100% |

| Participant 2 | 12 | 6 | 18 | 14 | 6 | 15 min to 2 h | 100% | 67% | 100% | 100% |

| Participant 3 | 8 | 6 | 14 | 21 | 10 | 5 min to 30 min | 100% | 50% | 100% | 100% |

| Participant 4 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 19 | 10 | 1 h to 6 h | 100% | 70% | 100% | 100% |

| Participant 5 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 18 | 9 | 15 min to 30 min | 78% | 67% | 100% | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Castro, M.J.; Severino, C.; Pejovic, J.; Vigário, M.; Palha, M.; de Andrade, D.C.; Frota, S. New Digital Workflow for the Use of a Modified Stimulating Palatal Plate in Infants with Down Syndrome. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010026

Castro MJ, Severino C, Pejovic J, Vigário M, Palha M, de Andrade DC, Frota S. New Digital Workflow for the Use of a Modified Stimulating Palatal Plate in Infants with Down Syndrome. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro, Maria Joana, Cátia Severino, Jovana Pejovic, Marina Vigário, Miguel Palha, David Casimiro de Andrade, and Sónia Frota. 2026. "New Digital Workflow for the Use of a Modified Stimulating Palatal Plate in Infants with Down Syndrome" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010026

APA StyleCastro, M. J., Severino, C., Pejovic, J., Vigário, M., Palha, M., de Andrade, D. C., & Frota, S. (2026). New Digital Workflow for the Use of a Modified Stimulating Palatal Plate in Infants with Down Syndrome. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010026