Knowledge and Expectations of Orthodontic Retention Among Individuals Seeking Orthodontic Treatment in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting and Participants

2.3. Sampling and Inclusion Criteria

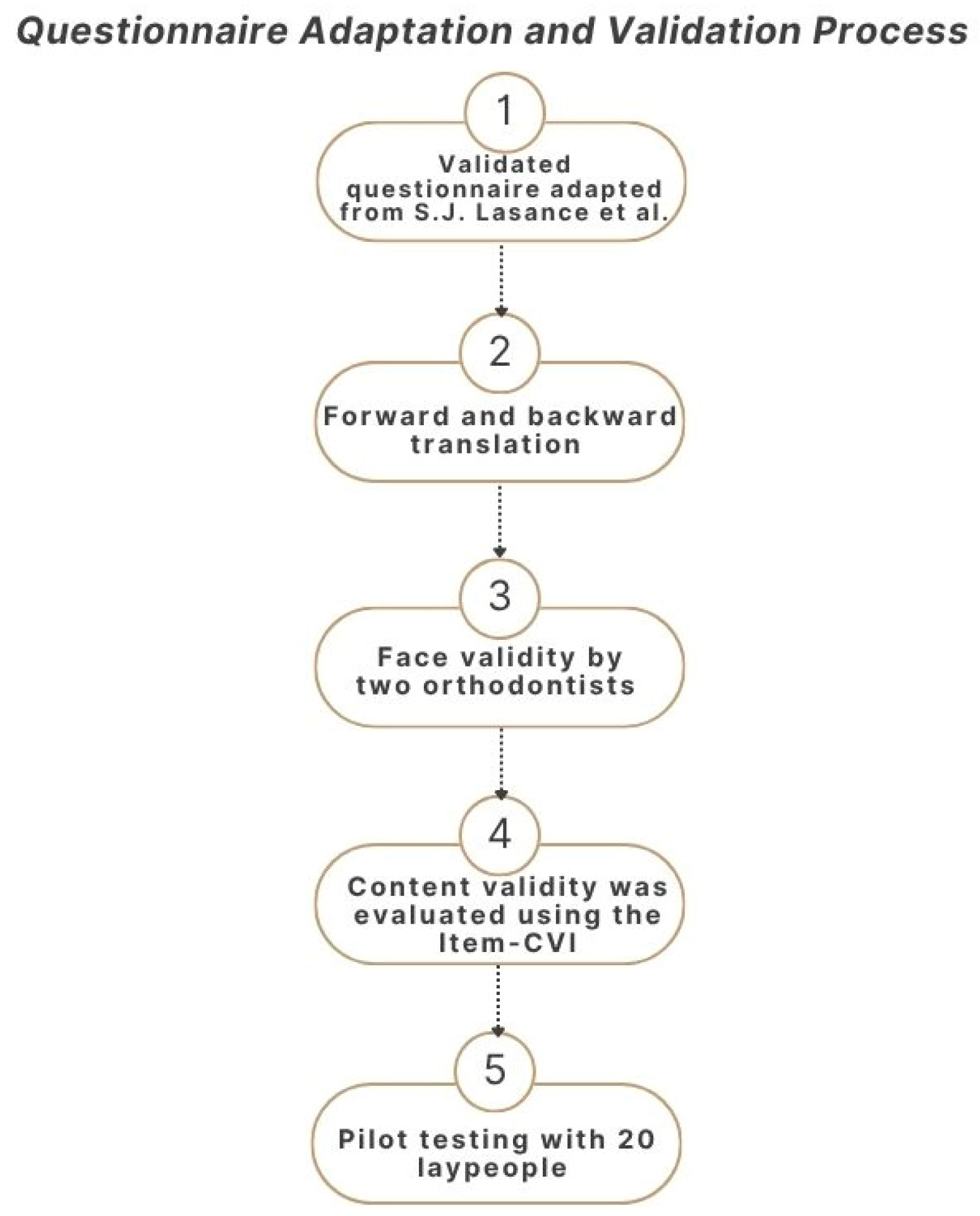

2.4. Data Collection Tool

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Knowledge on Orthodontic Retention

3.3. Expectations on Orthodontic Retention

3.4. Confidence Levels in Various Sources of Information on Orthodontic Retention

3.5. Relationship of Participants’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Their Knowledge and Expectation Toward Orthodontic Retention

3.6. Relationship Between Participants’ Confidence in Information Sources with Their Demographic Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KAUFD | King Abdulaziz University Faculty of Dentistry |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| I-CVI | Item-Content Validity Index |

| S-CVI | Scale-Content Validity Index |

| aOR | adjusted Odd Ratio |

| NS | Not Significant |

| CI | Confident Interval |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Martin, C.; Littlewood, S.J.; Millett, D.T.; Doubleday, B.; Bearn, D.; Worthington, H.V.; Limones, A. Retention procedures for stabilising tooth position after treatment with orthodontic braces. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 2023, CD002283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melrose, C.; Millett, D.T. Toward a perspective on orthodontic retention? Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1998, 113, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadowsky, C.; Sakols, E.I. Long-term assessment of orthodontic relapse. Am. J. Orthod. 1982, 82, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowsky, C.; Schneider, B.J.; BeGole, E.A.; Tahir, E. Long-term stability after orthodontic treatment: Nonextraction with prolonged retention. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1994, 106, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäderberg, S.; Feldmann, I.; Engström, C. Removable thermoplastic appliances as orthodontic retainers—A prospective study of different wear regimens. Eur. J. Orthod. 2012, 34, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, S.J.; Dalci, O.; Dolce, C.; Holliday, L.S.; Naraghi, S. Orthodontic retention: What’s on the horizon? Br. Dent. J. 2021, 230, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukala, E.; Lyros, I.; Tsolakis, A.I.; Maroulakos, M.P.; Tsolakis, I.A. Direct 3D-Printed Orthodontic Retainers. A Systematic Review. Children 2023, 10, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Al-Moghrabi, D.; Pandis, N.; Shah, S.; Fleming, P.S. The effectiveness of a bespoke mobile application in improving adherence with removable orthodontic retention over 12 months: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 161, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafaie, K.; Rizk, M.Z.; Basyouni, M.E.; Daniel, B.; Mohammed, H. Tele-orthodontics and sensor-based technologies: A systematic review of interventions that monitor and improve compliance of orthodontic patients. Eur. J. Orthod. 2023, 45, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, S.; Kandasamy, S.; Huang, G. Retention and relapse in clinical practice. Aust. Dent. J. 2017, 62, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karslı, N.; Ocak, I.; Gülnar, B.; Tüzüner, T.; Littlewood, S.J. Patient perceptions and attitudes regarding post-orthodontic treatment changes. Angle Orthod. 2023, 93, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.F.; Al-Attar, A.M.; Alhuwaizi, A.F. Retention Protocols and Factors Affecting Retainer Choice among Iraqi Orthodontists. Int. J. Dent. 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jewair, T.S.; Hamidaddin, M.A.; Alotaibi, H.M.; Alqahtani, N.D.; Albarakati, S.F.; Alkofide, E.A.; Al-Moammar, K.A. Retention practices and factors affecting retainer choice among orthodontists in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriekute, A.; Vasiliauskas, A.; Sidlauskas, A. A survey of protocols and trends in orthodontic retention. Prog. Orthod. 2017, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamran, T.; Čirgić, E.; Aiyar, A.; Vandevska-Radunovic, V. Survey on retention procedures and use of thermoplastic retainers among orthodontists in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2022, 11, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmos, J.A.D.; Fudalej, P.S.; Renkema, A.M. Epidemiologic study of orthodontic retention procedures. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 153, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenesha, F.; Elhabony, S. Orthodontic Patients’ Knowledge and Understanding of Orthodontic Retainers: A cross sectional study. Libyan J. Dent. 2022, 6, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasance, S.J.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Eliades, T.; Patcas, R. Post-orthodontic retention: How much do people deciding on a future orthodontic treatment know and what do they expect? A questionnaire-based survey. Eur. J. Orthod. 2020, 42, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollov, N.D.; Lindauer, S.J.; Best, A.M.; Shroff, B.; Tufekci, E. Patient attitudes toward retention and perceptions of treatment success. Angle Orthod. 2010, 80, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.; Freer, T.J. Patients’ attitudes towards compliance with retainer wear. Australas. Orthod. J. 2005, 21, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesler, D.J.; Auerbach, S.M. Optimal matches of patient preferences for information, decision-making and interpersonal behavior: Evidence, models and interventions. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 61, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, N.; Litaker, D.; Schaarschmidt, M.L.; Peitsch, W.K.; Schmieder, A.; Terris, D.D. Outcomes associated with matching patients’ treatment preferences to physicians’ recommendations: Study methodology. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, M.R. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs. Res. 1986, 35, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahida, H.K.; Memon, S.; Memon, J. Expectations of prospective orthodontic patients regarding post-orthodontic retention. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2024, 74, 2086–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, M.J.; Dreyer, C.W. Analysis of the information contained within TikTok videos regarding orthodontic retention. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2022, 11, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, M.J.; Sooriakumaran, P.; Dreyer, C.W. Orthodontic retention and retainers: Quality of information provided by dental professionals on YouTube. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2020, 158, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martina, S.; Cannatà, D.; Paduano, T.; Schettino, V.; Giordano, F.; Galdi, M. Reliability of Large Language Model-Based Chatbots Versus Clinicians as Sources of Information on Orthodontics: A Comparative Analysis. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Arqub, S.; Al-Moghrabi, D.; Allareddy, V.; Upadhyay, M.; Vaid, N.; Yadav, S. Content analysis of AI-generated (ChatGPT) responses concerning orthodontic clear aligners. Angle Orthod. 2024, 94, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdakurban, E.; Topsakal, K.G.; Duran, G.S. A comparative analysis of AI-based chatbots: Assessing data quality in orthognathic surgery related patient information. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 125, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhur, A.; Alhur, A.; Alshammari, M.; Alhur, A.; Bin Shamlan, W.; Alqahtani, M.; Alhabsi, S.; Hassan, R.; Baawadh, E.; Alahmari, S.; et al. Digital Health Literacy and Web-Based Health Information-Seeking Behaviors in the Saudi Arabian Population. Cureus 2023, 15, e51125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age: | ||

| 18–24 | 60 | 37.3 |

| 25–34 | 27 | 16.8 |

| 35–44 | 25 | 15.5 |

| 45–54 | 34 | 21.1 |

| 55+ | 15 | 9.3 |

| Gender: | ||

| Male | 77 | 47.8 |

| Female | 84 | 52.2 |

| Educational level: | ||

| Uneducated | 13 | 8.1 |

| High school or lower education | 63 | 39.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 64 | 39.8 |

| Postgraduate degree | 21 | 13.0 |

| Who is seeking treatment? | ||

| Respondent | 72 | 44.7 |

| Respondent’s child under 18 | 89 | 55.3 |

| Previous experiences with orthodontics within close family: | ||

| No | 68 | 42.2 |

| Yes | 93 | 57.8 |

| Reason for consultation: | ||

| Referral by someone | 46 | 28.6 |

| Self-motivated | 115 | 71.4 |

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Are you aware that appliances are used for retention after orthodontic treatment? | ||

| No | 61 | 37.9 |

| Yes | 100 | 62.1 |

| How often do you think such appliances are necessary? | ||

| In rare cases | 9 | 5.6 |

| In some cases | 73 | 45.3 |

| In most cases | 29 | 18.0 |

| In all cases | 50 | 31.1 |

| In which cases do you consider retention necessary? (Na = 216) * | ||

| After comprehensive orthodontic treatment | 61 | 37.9 |

| After orthodontic treatment during growth | 50 | 31.1 |

| After orthodontic treatment in adults | 22 | 13.7 |

| After treatment with extractions | 8 | 5.0 |

| In all cases | 75 | 46.6 |

| Do you believe a perfect treatment result can guarantee stability? | ||

| No | 31 | 19.3 |

| Yes | 130 | 80.8 |

| Do you think that teeth can also move without orthodontic appliances? | ||

| No | 70 | 43.5 |

| Yes | 91 | 56.5 |

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| How long do you think the retention phase should be? | ||

| Less than a year | 36 | 22.4 |

| 1–3 years | 92 | 57.1 |

| 3–10 years | 11 | 6.8 |

| Lifelong | 22 | 13.7 |

| How important is a stable result for you? | ||

| Not important | 2 | 1.2 |

| Ambivalent | 7 | 4.4 |

| Rather important | 56 | 34.8 |

| Extremely important | 96 | 59.6 |

| Which type of retention device would you favor? | ||

| Bonded device | 81 | 50.31 |

| Removable device | 80 | 49.69 |

| At which interval do you believe recall visits are necessary? | ||

| Every 3 months | 67 | 41.61 |

| Every 6 months | 53 | 32.92 |

| Yearly | 30 | 18.63 |

| Every 2nd year | 7 | 4.35 |

| Every 5th year | 4 | 2.48 |

| Who do you consider responsible for the stability after orthodontic treatment? (N = 263) * | ||

| General dentist | 26 | 16.1 |

| orthodontist | 113 | 70.2 |

| Patient/or parent | 124 | 77.0 |

| Do you think it is appropriate to charge for recall visits? | ||

| No | 151 | 93.79 |

| Yes | 10 | 6.21 |

| Very Not Confident (%) | Somewhat Not Confident (%) | Neutral (%) | Somewhat Confident (%) | Very Confident (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthodontist | 1 | 0 | 1 | 17 | 142 |

| (0.6) | (0.0) | (0.6) | (10.6) | (88.2) | |

| General dentist | 0 | 3 | 19 | 68 | 71 |

| (0.0) | (1.9) | (11.8) | (42.2) | (44.1) | |

| Friends and family | 3 | 23 | 38 | 67 | 30 |

| (1.9) | (14.3) | (23.6) | (41.6) | (18.6) | |

| Online searches | 9 | 24 | 44 | 68 | 16 |

| (5.6) | (14.9) | (27.3) | (42.2) | (9.9) | |

| Social media | 12 | 34 | 49 | 54 | 12 |

| (7.5) | (21.1) | (30.4) | (33.5) | (7.5) | |

| Artificial Intelligence Chatbots | 13 | 26 | 38 | 60 | 24 |

| (8.1) | (16.2) | (23.6) | (37.3) | (14.9) |

| Gender 1 | Age 2 | Education 3 | Past Experiences 4 | Consultation Reason 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant is aware that retention devices are being used after orthodontic treatment | NS | NS | NS | aOR = 4.91 CI = (2.35–10.24) p-value < 0.001 q-value = 0.001 | NS |

| Participant believes a perfect result guarantees stability | NS | NS | NS | aOR = 3.05 CI = (1.30–7.16) p-value = 0.011 q-value = 0.321 | NS |

| Participant thinks that the retention phase should be lifelong | NS | aOR = 0.25 CI = (0.08–0.8) p-value = 0.017 q-value = 0.608 | aOR = 7.83 CI = (2.11–29.1) p-value = 0.002 q-value = 0.076 | NS | NS |

| Participant thinks teeth can move without orthodontics | NS | NS | NS | NS | aOR = 2.41 CI = (1.14–5.10) p-value = 0.021 q-value = 0.630 |

| Patient favors removable over fixed retainer | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Participant believes it is appropriate to charge for recall visits | NS | NS | NS | NS | aOR = 0.21 CI = (0.05–0.85) p-value = 0.029 q-value = 0.885 |

| Gender 1 | Age 2 | Education 3 | Past Experiences 4 | Consultation Reason 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthodontist | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| General dentist | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Friends and family | NS | NS | aOR = 0.45 CI = 0.23–0.90 p-value = 0.025 q-value = 0.836 | NS | NS |

| Online searches | NS | NS | NS | NS | aOR = 2.74 CI = 1.27–5.94 p-value = 0.011 q-value = 0.360 |

| Social media | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Artificial Intelligence Chatbots | NS | NS | NS | aOR = 2.77 CI = 1.40–5.50 p-value = 0.003 q-value = 0.118 | NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Helal, N.M.; Saber, N.O.; Almalki, M.F.; Basri, O.A. Knowledge and Expectations of Orthodontic Retention Among Individuals Seeking Orthodontic Treatment in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010021

Helal NM, Saber NO, Almalki MF, Basri OA. Knowledge and Expectations of Orthodontic Retention Among Individuals Seeking Orthodontic Treatment in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleHelal, Narmin M., Nujud O. Saber, Mohammed F. Almalki, and Osama A. Basri. 2026. "Knowledge and Expectations of Orthodontic Retention Among Individuals Seeking Orthodontic Treatment in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010021

APA StyleHelal, N. M., Saber, N. O., Almalki, M. F., & Basri, O. A. (2026). Knowledge and Expectations of Orthodontic Retention Among Individuals Seeking Orthodontic Treatment in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010021