Sex-Specific Associations with Periodontal Inflammation and Bone Loss: A Cross-Sectional Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- ➢

- Initial examination at baseline

- ○

- Participants age ≥18 years

- ○

- Diagnosis of periodontitis Stage II bis IV

- ➢

- Complete dental and periodontal examination

- ➢

- Radiographic examination ≤ 12 months prior to clinical examination

- ➢

- Smoking status (non-smoker, former smoker (≥5 years), smoker)

- ➢

- Detailed medical history focusing on specific diseases or disorders (Figure 1)

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Clinical Data Collection

2.3. Radiographic and Demographic Data

2.4. Bias Considerations and Data Quality

2.5. Sample Size and Post Hoc Power Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

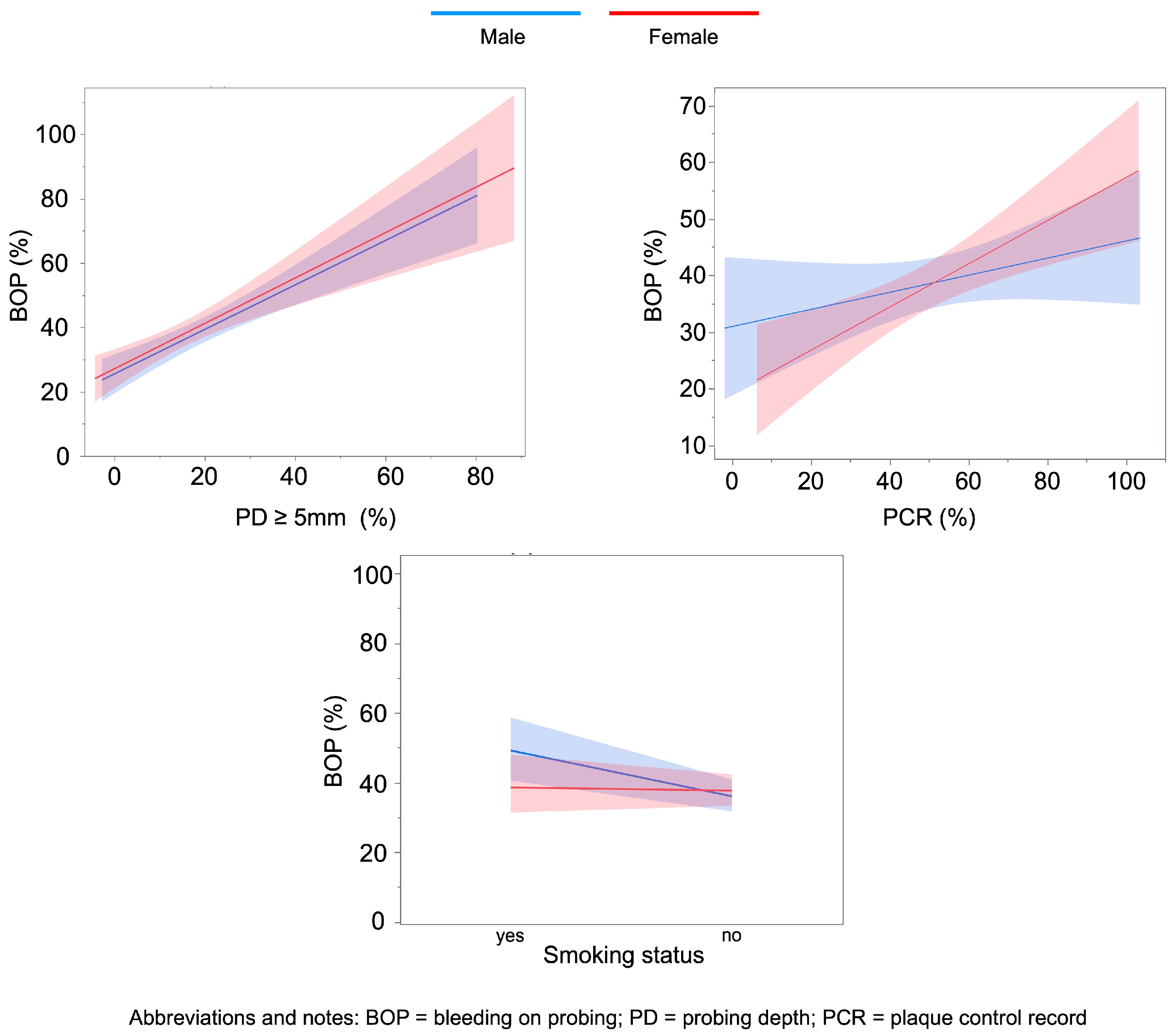

3.1. Factors Associated with BOP (%) in Females and Males

3.2. Factors Associated with Bone Loss Index

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

- (1)

- The retrospective design represents a methodological limitation, as the analysis was confined to pre-existing documentation. Consequently, relevant information may be missing either due to a lack of perceived importance at the time of data collection or due to unintentional omissions in the clinical records.

- (2)

- One of these missing and at that time not collected data points concerns the HbA1c value, which was recorded very inadequately and is still hardly ever known by the patient today.

- (3)

- Another data gap concerns the exact smoking behaviour. Although it was recorded whether the patient smokes, quit smoking (for at least 5 years), or is a non-smoker, the precise number of cigarettes or packs per day was not asked during the medical history interview at that time. The amount of cigarettes actually consumed certainly has a not insignificant influence.

- (4)

- The patient examinations were conducted by uncalibrated examiners. However, the recording of dental and periodontal parameters adhered to a very strict protocol.

- (5)

- The timing within the female menstrual cycle was not recorded (potential for additional hormonal influence); however, the median age of 57 among female participants suggests a predominantly postmenopausal cohort.

- (6)

- Potentially relevant dietary and lifestyle factors influencing periodontal inflammation were not assessed in this study.

- (7)

- It should also be noted that the bacterial flora of the patients was not examined; therefore, patients with particularly aggressive periodontal pathogens could not be selected.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHA | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| BLI | Bone loss Index |

| BOP | Bleeding on probing |

| CEJ | Cementoenamel junction |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| HbA1c | glycated hemoglobin (hemoglobin A1c) |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| LDL | low-density protein |

| PCR | Plaque control record |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| AIDS | Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome |

| PD | pocket depth |

| RANKL | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor kappa-B Ligand |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SS LepR | Dahl salt-sensitive (rat strain), Leptin receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

References

- Collins, F.S.; Fink, L. The Human Genome Project. Alcohol. Health Res. World 1995, 19, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 2004, 431, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcangi, G.; Patano, A.; Guglielmo, M.; Sardano, R.; Palmieri, G.; Di Pede, C.; de Ruvo, E.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Mancini, A.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Precision Medicine in Oral Health and Diseases: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J. The Impact of Female Hormones on the Periodontium-A Narrative Review. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2025, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannobile, W.V.; Kornman, K.S.; Williams, R.C. Personalized medicine enters dentistry: What might this mean for clinical practice? J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2013, 144, 874–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidou, E. The Sex and Gender Intersection in Chronic Periodontitis. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagis, B.; Ayaz, E.A.; Turgut, S.; Durkan, R.; Özcan, M. Gender difference in prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular joint disorders: A population-based study. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 9, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, H.J.; Reynolds, M.A. Sex differences in destructive periodontal disease: A systematic review. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangalli, L.; Souza, L.C.; Letra, A.; Shaddox, L.; Ioannidou, E. Sex as a Biological Variable in Oral Diseases: Evidence and Future Prospects. J. Dent. Res. 2023, 102, 1395–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Mianecki, M.; Maglaras, V.; Sheikh, A.; Saleh, M.H.A.; Decker, A.M.; Decker, J.T. Neutrophils drive sexual dimorphism in experimental periodontitis. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, R.; Simonelli, A.; Tomasi, C.; Ioannidou, E.; Trombelli, L. Sexual dimorphism in periodontal inflammation: A cross-sectional study. J. Periodontol. 2025, 96, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pinto, R.; Ferri, C.; Giannoni, M.; Cominelli, F.; Pizarro, T.T.; Pietropaoli, D. Meta-analysis of oral microbiome reveals sex-based diversity in biofilms during periodontitis. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e171311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chen, S.W.; Su, W.L.; Zhu, H.Y.; Ouyang, S.Y.; Cao, Y.T.; Jiang, S.Y. Sex Hormones Enhance Gingival Inflammation without Affecting IL-1β and TNF-α in Periodontally Healthy Women during Pregnancy. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 4897890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, C.C.; Sloniak, M.C.; Assis, J.B.d.; Porto, R.C.; Romito, G.A. Unveiling sex-disparities and the impact of gender-affirming hormone therapy on periodontal health. Front. Dent. Med. 2024, 5, 1430193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawed, S.T.M.; Tul Kubra Jawed, K. Understanding the Link Between Hormonal Changes and Gingival Health in Women: A Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e85270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirel, K.J.; Guimaraes, A.N.; Demirel, I. Effects of estradiol on the virulence traits of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markou, E.; Eleana, B.; Lazaros, T.; Antonios, K. The influence of sex steroid hormones on gingiva of women. Open Dent. J. 2009, 3, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, M.S.; Su, S.; Crespo, C.J.; Hung, M. Men and Oral Health: A Review of Sex and Gender Differences. Am. J. Mens. Health 2021, 15, 15579883211016361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Lipsky, M.S.; Licari, F.W.; Hung, M. Comparing oral health behaviours of men and women in the United States. J. Dent. 2022, 122, 104157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, V.; Mohr, J.; Krumm, B.; Herz, M.M.; Wolff, D.; Petsos, H. Minimal periodontal basic care—No surgery, no antibiotics, low adherence. What can be expected? A retrospective data analysis. Quintessence Int. 2022, 53, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, M.M.; Hoffmann, N.; Braun, S.; Lachmann, S.; Bartha, V.; Petsos, H. Periodontal pockets: Predictors for site-related worsening after non-surgical therapy-A long-term retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, M.M.; Schamuhn, J.; Krumm, B.; Bartha, V. Student-performed periodontal therapy: Retrospective cohort study on outcomes and related recommendations for enhancing undergraduate periodontal education. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, T.J.; Drake, R.B.; Naylor, J.E. The plaque control record. J. Periodontol. 1972, 43, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, P.; Dannewitz, B.; Nickles, K.; Petsos, H.; Eickholz, P. Assessment of periodontitis grade in epidemiological studies using interdental attachment loss instead of radiographic bone loss. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumm, C.V.; Ern, C.; Folwaczny, J.; Wölfle, U.C.; Heck, K.; Werner, N.; Folwaczny, M. Periodontal grading—Estimation of responsiveness to therapy and progression of disease. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédard, A.; Lamarche, B.; Corneau, L.; Dodin, S.; Lemieux, S. Sex differences in the impact of the Mediterranean diet on systemic inflammation. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelber, J.P.; Bartha, V.; Baumgartner, S.; Tennert, C.; Schlagenhauf, U.; Ratka-Krüger, P.; Vach, K. Is Diet a Determining Factor in the Induction of Gingival Inflammation by Dental Plaque? A Secondary Analysis of Clinical Studies. Nutrients 2024, 16, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuta, M.; Ekuni, D.; Irie, K.; Azuma, T.; Tomofuji, T.; Ogura, T.; Morita, M. Sex differences in gingivitis relate to interaction of oral health behaviors in young people. J. Periodontol. 2011, 82, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, T.; Bernimoulin, J.P.; Glynn, R.J. The effect of cigarette smoking on gingival bleeding. J. Periodontol. 2004, 75, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, S.G.; Genco, R.J.; Machtei, E.E.; Ho, A.W.; Koch, G.; Dunford, R.; Zambon, J.J.; Hausmann, E. Assessment of risk for periodontal disease. II. Risk indicators for alveolar bone loss. J. Periodontol. 1995, 66, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, G.M.; Lucas, G.Q.; Lucas, O.N. Cigarette smoking and alveolar bone in young adults: A study using digitized radiographs. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, K.Y.; Jang, Y.S.; Jang, Y.S.; Nerobkova, N.; Park, E.C. Association between Smoking and Periodontal Disease in South Korean Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosseva-Panova, V.; Pashova-Tasseva, Z.; Mlachkova, A. Relationship of several risk factors in periodontitis: Smoking, gender, age and microbiological finding. J. IMAB–Annu. Proc. Sci. Pap. 2023, 29, 4877–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, H.J. Periodontal disease in women and men. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2018, 5, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.B.; Reinhardt, R.A.; Nummikoski, P.V.; Dunning, D.G.; Patil, K.D. The association of cigarette smoking with alveolar bone loss in postmenopausal females. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2000, 27, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albandar, J.M. Global risk factors and risk indicators for periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000, 2002, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liechti, L.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Gebert, P.; Schmidlin, P.R.; Campus, G. Sex and gender differences in periodontal disease: A cross-sectional study in Switzerland. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.B.; Wikle, J.C. Sex differences in inflammatory and apoptotic signaling molecules in normal and diseased human gingiva. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, 1612–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.; Gleason, R.C.; Li, F.; Hosur, K.B.; Duan, X.; Huang, D.; Wang, H.; Hajishengallis, G.; Liang, S. Sex dimorphism in periodontitis in animal models. J. Periodontal Res. 2016, 51, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhashim, A.; Capehart, K.; Tang, J.; Saad, K.M.; Abdelsayed, R.; Cooley, M.A.; Williams, J.M.; Elmarakby, A.A. Does Sex Matter in Obesity-Induced Periodontal Inflammation in the SS(LepR) Mutant Rats? Dent. J. 2024, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmayanti, A.W.S.; Setiawatie, E.M.; Hendarto, H. Sex-Based Differences in Gingival Inflammatory Responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis in Male and Female Rats. Trends Sci. 2025, 22, 9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Nickel, J.C.; Iwasaki, L.R.; Duan, P.; Simmer-Beck, M.; Brown, L. Gender differences in the association of periodontitis and type 2 diabetes. Int. Dent. J. 2018, 68, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Total (Mean ± SD) | Men (Mean ± SD) | Women (Mean ± SD) | p-Value (Male vs. Female) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.6 ± 11.6 | 55.4 ± 11.8 | 55.8 ± 11.5 | 0.758 |

| PD ≥ 5 mm (%) | 17.4 ± 14.8 | 19.6 ± 15.2 | 15.3 ± 14.2 | 0.030 * |

| BOP (%) | 38.4 ± 23.4 | 39.0 ± 23.5 | 37.9 ± 23.5 | 0.717 |

| PCR (%) | 51.0 ± 20.2 | 52.6 ± 20.1 | 49.5 ± 20.2 | 0.072 |

| Bone loss index | 0.95 ± 0.51 | 1.01 ± 0.51 | 0.89 ± 0.51 | 0.060 |

| Smoking (yes) | 24.6% | 22.8% | 26.3% | 0.547 |

| Diabetes (yes) | 8.6% | 9.6% | 7.6% | 0.645 |

| Predictor | Men: Estimate (95% CI) | p-Value | Women: Estimate (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | 0.16 (0.02; 0.31) | 0.029 * | –0.03 (–0.16; 0.09) | 0.587 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | –0.07 (–0.26; 0.12) | 0.471 | 0.13 (–0.07; 0.33) | 0.194 | |

| PD ≥ 5 mm (%) | 1.52 (0.86; 2.19) | <0.001 * | 1.39 (0.53; 2.25) | 0.002 * | |

| Age (years) | 20–29 | –0.21 (–1.21; 0.80) | 0.683 | 0.35 (–0.17; 0.87) | 0.186 |

| 30–39 | 0.09 (–0.32; 0.49) | 0.667 | 0.06 (–0.32; 0.45) | 0.739 | |

| 40–49 | 0.05 (–0.26; 0.36) | 0.756 | –0.13 (–0.39; 0.12) | 0.305 | |

| 50–59 | –0.11 (–0.41; 0.18) | 0.453 | –0.09 (–0.31; 0.13) | 0.419 | |

| 60–69 | 0.10 (–0.22; 0.42) | 0.526 | –0.08 (–0.30; 0.14) | 0.473 | |

| Ref. Age ≥ 70 | – | – | – | – | |

| Number of teeth | –0.002 (–0.03; 0.03) | 0.912 | 0.03 (–0.01; 0.06) | 0.128 | |

| PCR (%) | 0.005 (–0.0004; 0.01) | 0.071 | 0.009 (0.003; 0.015) | 0.003 * | |

| Predictor | Men: Estimate (95% CI) | p-Value | Women: Estimate (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | 0.06 (–0.12; 0.25) | 0.483 | 0.13 (0.03; 0.21) | 0.010 * |

| Diabetes mellitus | –0.07 (–0.30; 0.17) | 0.564 | –0.01 (–0.19; 0.17) | 0.912 |

| Number of teeth | –0.03 (–0.08; 0.02) | 0.288 | –0.01 (–0.05; 0.03) | 0.545 |

| PCR (%) | –0.008 (–0.016; –0.0002) | 0.042 * | 0.0002 (–0.0045; 0.0049) | 0.941 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bartha, V.; Schamuhn, J.; Krumm, B.; Herz, M.M. Sex-Specific Associations with Periodontal Inflammation and Bone Loss: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Dent. J. 2026, 14, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010011

Bartha V, Schamuhn J, Krumm B, Herz MM. Sex-Specific Associations with Periodontal Inflammation and Bone Loss: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Dentistry Journal. 2026; 14(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartha, Valentin, Judith Schamuhn, Boris Krumm, and Marco M. Herz. 2026. "Sex-Specific Associations with Periodontal Inflammation and Bone Loss: A Cross-Sectional Analysis" Dentistry Journal 14, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010011

APA StyleBartha, V., Schamuhn, J., Krumm, B., & Herz, M. M. (2026). Sex-Specific Associations with Periodontal Inflammation and Bone Loss: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Dentistry Journal, 14(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj14010011