Clinical Management of Worn Ball Abutments in Mandibular Mini-Implant Overdentures: A Case Report in a Skeletal Class II Patient

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Case Report: Patient with Skeletal Class II Relationship

2.1. Clinical and Radiological Examination

2.2. The Implant-Prosthetic Treatment Plan

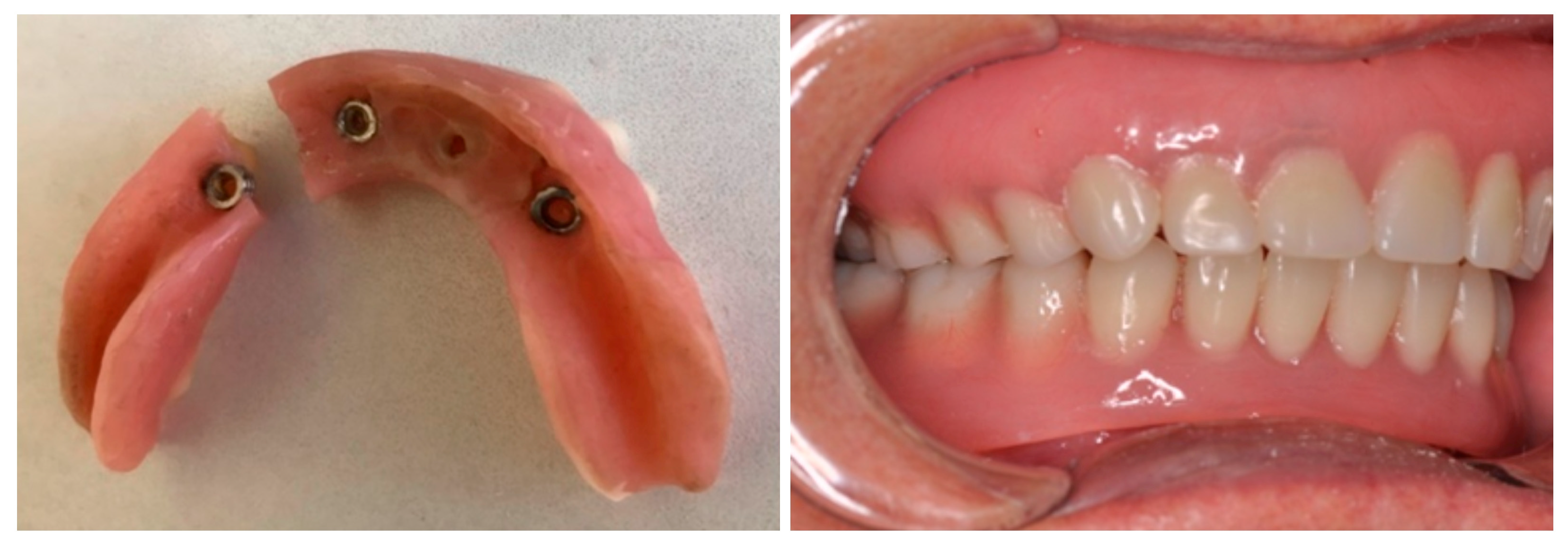

2.3. Fractures of Mandibular Overdentures and the Occurrence of Ball Abutments Wear

2.4. Prosthetic Alternatives for Managing Complications Associated with Ball Abutment Wear

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carlsson, G.E.; Omar, R. The future of complete dentures in oral rehabilitation. A critical review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms: Ninth Edition. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 117, e1–e105. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, T.A.; Langer, Y.; Curtis, D.A.; Carpenter, R. Occlusal considerations for partially or completely edentulous skeletal class II patients. Part I: Background information. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1988, 60, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pommer, B.; Mailath-Pokorny, G.; Haas, R.; Busenlechner, D.; Fürhauser, R.; Watzek, G. Patients’ preferences towards minimally invasive treatment alternatives for implant rehabilitation of edentulous jaws. Eur. J. Oral Implantol. 2014, 7, S91–S109. [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorne, L.; Vandeweghe, S.; Matthys, C.; Vermeersch, H.; Bronkhorst, E.; Meijer, G.; De Bruyn, H. Five years clinical outcome of maxillary mini dental implant overdenture treatment: A prospective multicenter clinical cohort study. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2023, 25, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celebic, A.; Kovacic, I.; Petricevic, N.; Alhajj, M.N.; Topic, J.; Junakovic, L.; Persic-Kirsic, S. Clinical Outcomes of Three versus Four Mini-Implants Retaining Mandibular Overdenture: A 5-Year Randomized Clinical Trial. Medicina 2023, 60, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshenaiber, R.; Barclay, C.; Silikas, N. The Effect of Mini Dental Implant Number on Mandibular Overdenture Retention and Attachment Wear. BioMed Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 7099761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feine, J.S.; Carlsson, G.E.; Awad, M.A.; Chehade, A.; Duncan, W.J.; Gizani, S.; Head, T.; Heydecke, G.; Lund, J.P.; MacEntee, M.; et al. The McGill consensus statement on overdentures. Mandibular two-implant overdentures as first choice standard of care for edentulous patients. Gerodontology 2002, 19, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Thomason, J.M.; Feine, J.; Exley, C.E.; Moynihan, P.; Müller, F.; Naert, I.; Ellis, J.S.; Barclay, C.; Butterworth, C.; Scott, B.; et al. Mandibular Two Implant-Supported Overdentures as the First Choice Standard of Care for Edentulous Patients—The York consensus statement on implant-supported overdentures. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2009, 17, 185–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P.W.; Nogueira, P.J.; Nobre, M.A.d.A.; Guedes, C.M.; Salvado, F. Impact of Mechanical Complications on Success of Dental Implant Treatments: A Case–Control Study. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 16, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, C.; Preoteasa, E.; Preoteasa, C.T.; Murariu-Măgureanu, C.; Teodorescu, I.M. The Biomechanical Impact of Loss of an Implant in the Treatment with Mandibular Overdentures on Four Nonsplinted Mini Dental Implants: A Finite Element Analysis. Materials 2022, 15, 8662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preoteasa, E.; Florica, L.I.; Obadan, F.; Imre, M.; Preoteasa, C.T. Minimally Invasive Implant Treatment Alternatives for the Edentulous Patient—Fast & Fixed and Implant Overdentures. In Current Concepts in Dental Implantology; Turkyilmaz, I., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mirchandani, B.; Zhou, T.; Heboyan, A.; Yodmongkol, S.; Buranawat, B. Biomechanical Aspects of Various Attachments for Implant Overdentures: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodacre, C.J.; Bernal, G.; Rungcharassaeng, K.; Kan, J.Y. Clinical complications with implants and implant prostheses. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 90, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Alla, I.; Lorusso, F.; Tari, S.R.; Gehrke, S.A.; Khater, A.G.A. Patients’ Satisfaction with Mandibular Overdentures Retained Using Mini-Implants: An Up-to-16-Year Cross-Sectional Study. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarb, G.; Schmitt, A. THE EDENTULOUS PREDICAMENT. I: A PROSPECTIVE STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF IMPLANT-SUPPORTED FIXED PROSTHESES. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1996, 127, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Lee, J.-Y.; Shin, S.-W.; Bryant, S.R. Attachment systems for mandibular implant overdentures: A systematic review. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2012, 4, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.; Faverani, L.P.; Junior, J.F.S.; Sukotjo, C.; Yuan, J.C.-C. Attachment systems for mandibular implant-supported overdentures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 132, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhohrah, T.; Mashrah, M.A.; Wang, Y. Effect of 2-implant mandibular overdenture with different attachments and loading protocols on peri-implant health and prosthetic complications: A systematic review and network. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunçāo, W.G.; Barāo, V.A.R.; Tabata, L.F.; De Sousa, E.A.C.; Gomes, E.A.; Delben, J.A. Comparison between complete denture and implant-retained overdenture: Effect of different mucosa thickness and resiliency on stress distribution. Gerodontology 2009, 26, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsyad, M.A.; Errabti, H.M.; Mustafa, A.Z. Mandibular Denture Base Deformation with Locator and Ball Attachments of Implant-Retained Overdentures. J. Prosthodont. 2015, 25, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.P.; Freilich, M.A.; Latvis, C.J. Fiber-reinforced composite framework for implant-supported overdentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2000, 84, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.H. Metal reinforcement for implant-supported mandibular overdentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2000, 83, 511–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonda, T.; Maeda, Y.; Walton, J.N.; MacEntee, M.I. Fracture incidence in mandibular overdentures retained by one or two implants. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2010, 103, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puljic, D.; Petricevic, N.; Celebic, A.; Kovacic, I.; Milos, M.; Pavic, D.; Milat, O. Mandibular Overdenture Supported by Two or Four Unsplinted or Two Splinted Ti-Zr Mini-Implants: In Vitro Study of Peri-Implant and Edentulous Area Strains. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolianos, I.; Haidich, A.-B.; Goulis, D.G.; Kotsiomiti, E. The effect of mandibular implant overdentures on masticatory performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent. Rev. 2023, 3, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshenaiber, R.; Barclay, C.; Silikas, N. The Effect of Number and Distribution of Mini Dental Implants on Overdenture Stability: An In Vitro Study. Materials 2022, 15, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batisse, C.; Bonnet, G.; Bessadet, M.; Veyrune, J.; Hennequin, M.; Peyron, M.; Nicolas, E. Stabilization of mandibular complete dentures by four mini implants: Impact on masticatory function. J. Dent. 2016, 50, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preoteasa, E.; Moraru, A.M.O.; Meghea, D.; Magureanu, C.M.; Preoteasa, C.T. Food Bolus Properties in Relation to Dentate and Prosthetic Status. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuhisa, M.; Matsushita, Y.; Koyano, K. In vitro study of a mandibular implant overdenture retained with ball, magnet, or bar attachments: Comparison of load transfer and denture stability. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2003, 16, 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gibreel, M.; Perea-Lowery, L.; Lassila, L.; Vallittu, P.K. Mechanical Properties Evaluation of Three Different Materials for Implant Supported Overdenture: An In-Vitro Study. Materials 2022, 15, 6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.-C.; Yang, T.C. Metal framework reinforcement in implant overdenture fabricated with a digital workflow and the double milling technique: A dental technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 134, 2088–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özçelik, T.B.; Yılmaz, B.; Akçimen, Y. Metal reinforcement for implant-supported mandibular overdentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2013, 109, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grageda, E.; Rieck, B. Metal-reinforced single implant mandibular overdenture retained by an attachment: A clinical report. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 111, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preoteasa, C.T.; Duță, K.A.; Tudose, B.F.; Murariu-Măgureanu, C.; Preoteasa, E. Digital Analysis of Closest Speaking Space in Dentates—Method Proposal and Preliminary Findings. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murariu-Măgureanu, C.; Preoteasa, E.; Teodorescu, C.; Preoteasa, C.T. Clinical Management of Worn Ball Abutments in Mandibular Mini-Implant Overdentures: A Case Report in a Skeletal Class II Patient. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120606

Murariu-Măgureanu C, Preoteasa E, Teodorescu C, Preoteasa CT. Clinical Management of Worn Ball Abutments in Mandibular Mini-Implant Overdentures: A Case Report in a Skeletal Class II Patient. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):606. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120606

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurariu-Măgureanu, Cătălina, Elena Preoteasa, Cristian Teodorescu, and Cristina Teodora Preoteasa. 2025. "Clinical Management of Worn Ball Abutments in Mandibular Mini-Implant Overdentures: A Case Report in a Skeletal Class II Patient" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120606

APA StyleMurariu-Măgureanu, C., Preoteasa, E., Teodorescu, C., & Preoteasa, C. T. (2025). Clinical Management of Worn Ball Abutments in Mandibular Mini-Implant Overdentures: A Case Report in a Skeletal Class II Patient. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120606