Evaluating the Diagnostic Proficiency Among a Sample of Final Stage Dental Students in Some Orthodontic Cases: A Comprehensive Analysis of Clinical Competence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire

- 1.

- Is orthodontic treatment essential for this patient?

- a.

- Yes.

- b.

- No.

- 2.

- If your answer is Yes, is orthognathic surgery necessary for this patient?

- a.

- Yes.

- b.

- No.

- 3.

- If your answer is Yes, what are the causes for this patient needing orthognathic surgery?

- a.

- Unaesthetic profile and alignment of teeth.

- b.

- Unaesthetic alignment of teeth.

- 4.

- If your answer is (A), what are the factors contributing to the unaesthetic profile?

- a.

- Protruded mandibular position.

- b.

- Retruded mandibular position.

- c.

- Protruded maxillary position.

- d.

- Retruded maxillary position.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

- 1.

- Curriculum improvement: Dental schools should modify their curricula to maintain an equilibrium of knowledge while offering sufficient opportunity for application. Offering integrated teaching strategies such as lectures with clinical experiences will help students with their practical applications.

- 2.

- Standardization of learning goals: Developing standard learning outcomes and competencies in orthodontic education across institutions may aid in further consistency. Additionally, the curriculum can be aligned to regulatory organizations so students will be prepared for professional practice expectations.

- 3.

- More clinical exposure: Clinical oversight during diverse clinical experiences with varying malocclusions and treatment planning opportunities will develop students’ diagnostic values. Clinical rotations and mentorships can add to experiences during school and offer clinic and patient care instruction.

- 4.

- Innovative teaching styles: The use of simulation-based training, case-based learning, and role playing becomes more essential as students increase clinical reasoning and decision making. Utilizing strategies that encourage realistically replicating their learning and undertaking obstacles to their learning opportunity provides students with opportunities to implement previously learnt concepts and theories in new practical environments.

- 5.

- Ongoing assessment: Formative assessment and feedback can put students in a position to develop good self-awareness of strong and weak abilities. It can also contribute to self-directed learning and skill building through ongoing reflective practice.

- 6.

- Faculty development: By investing in faculty–student training to embrace innovative teaching and assessment strategies, the faculty will improve their changing role in orthodontic education for students. The faculty should be both professionally and pedagogically equipped to create and use active learning opportunities while providing mentoring.

- 1.

- More structured clinical exposure to borderline cases.

- 2.

- More training in cephalometrics and reading facial profiles.

- 3.

- More use of 3D imaging and visual devices to reinforce diagnosis.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. (Clinical Cases Exam)

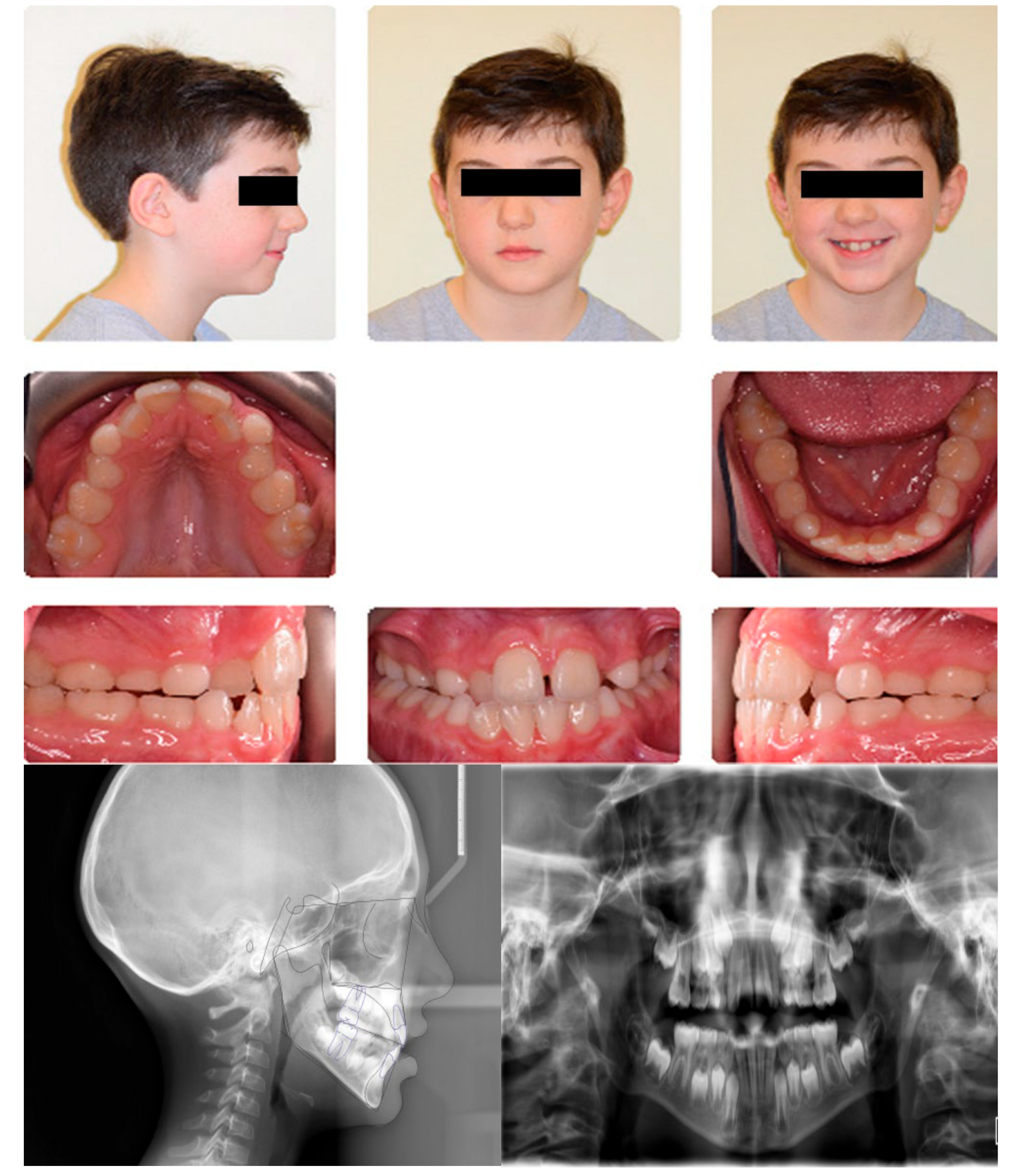

Appendix A.1. Case 1

| Age | 8 years | Over Jet = 1 mm |

| Sex | Male | Over bite = 1 mm |

| Breathing | Nasal | |

| Cephalometric analysis | ||

| Normal values | Patient values | |

| SNA | 80 | 78.6° |

| SNB | 78 | 75.9° |

| ANB | 2 | +2.7° |

| FMA | 21 | 30.2° |

| SN-GoGn | 32 | 41.4° |

| Maxillary incisor to SN | 105 | 97.4° |

| Mandibular incisor to GoGn | 95 | 85.5° |

| Soft tissue | ||

| Lower lip to E-plane | –2.0 mm | +0.4 mm |

| Upper lip to E-plane | –1.6 mm | –3.5 mm |

Appendix A.2. Case 2

| Age | 11 years | Over Jet = 3 mm |

| Sex | Male | Over bite = 5 mm |

| Breathing | Nasal | |

| Cephalometric analysis | ||

| Normal values | Patient values | |

| SNA | 80 | 86.4° |

| SNB | 78 | 82.7° |

| ANB | 2 | +3.7° |

| FMA | 21 | 23° |

| SN-GoGn | 32 | 27.8° |

| Maxillary incisor to SN | 105 | 103.8° |

| Mandibular incisor to GoGn | 95 | 96.3° |

| Soft tissue | ||

| Lower lip to E-plane | –2.0 mm | −3.1 mm |

| Upper lip to E-plane | –1.6 mm | −3.1 mm |

Appendix A.3. Case 3

| Age | 11 years | Over Jet = 4 mm |

| Sex | Male | Over bite = 8 mm |

| Breathing | Nasal | |

| Cephalometric analysis | ||

| Normal values | Patient values | |

| SNA | 80 | 80.2° |

| SNB | 78 | 75.6° |

| ANB | 2 | +4.3° |

| FMA | 21 | 24.2° |

| SN-GoGn | 32 | 38.1° |

| Maxillary incisor to SN | 105 | 83.3° |

| Mandibular incisor to GoGn | 95 | 83.3° |

| Soft tissue | ||

| Lower lip to E-plane | –2.0 mm | −4.9 mm |

| Upper lip to E-plane | –1.6 mm | −4.4 mm |

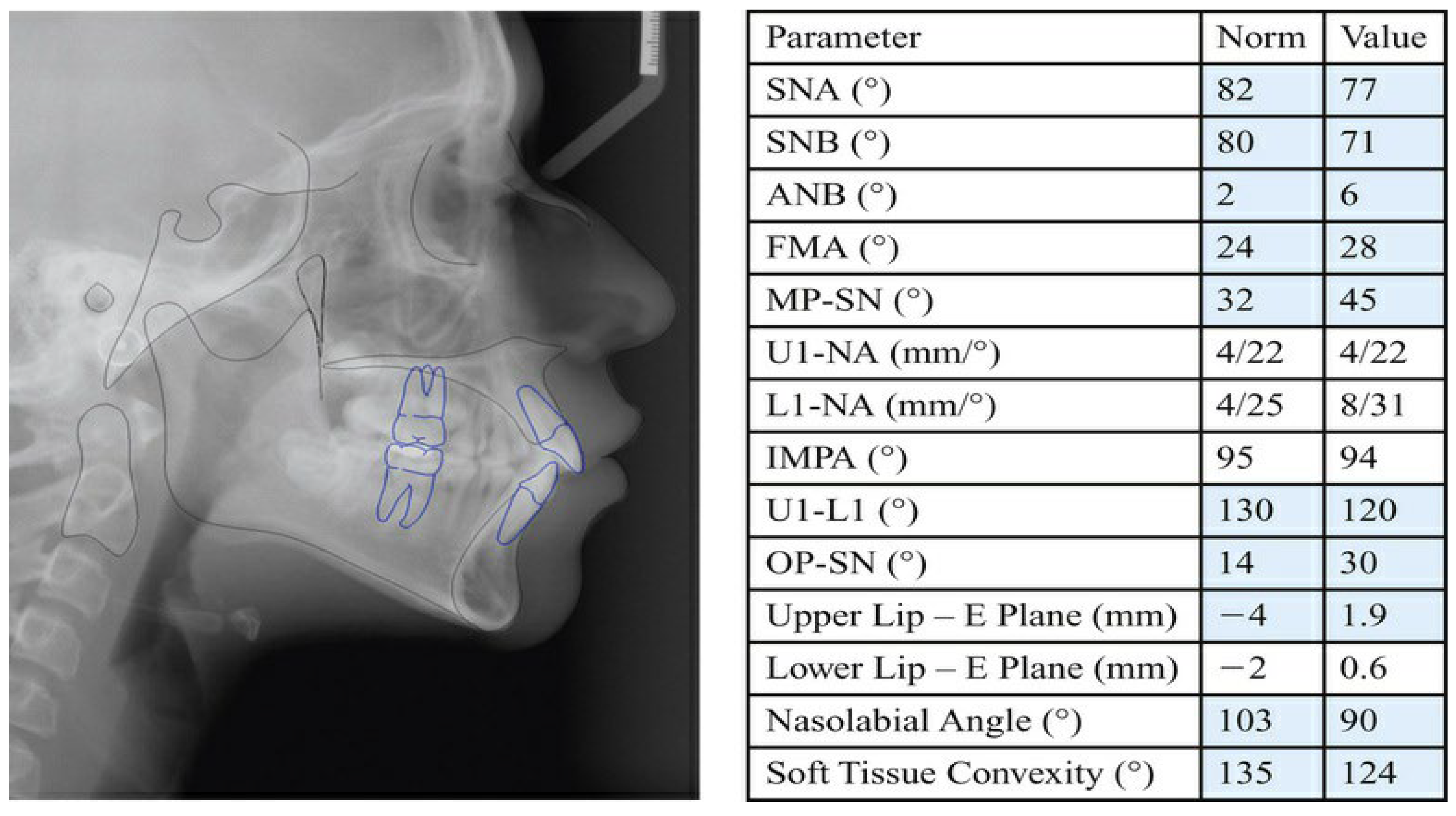

Appendix A.4. Case 4

| Age | 14 years | Over Jet = 3 mm |

| Sex | Female | Open bite = 4 mm |

| Breathing | Nasal |

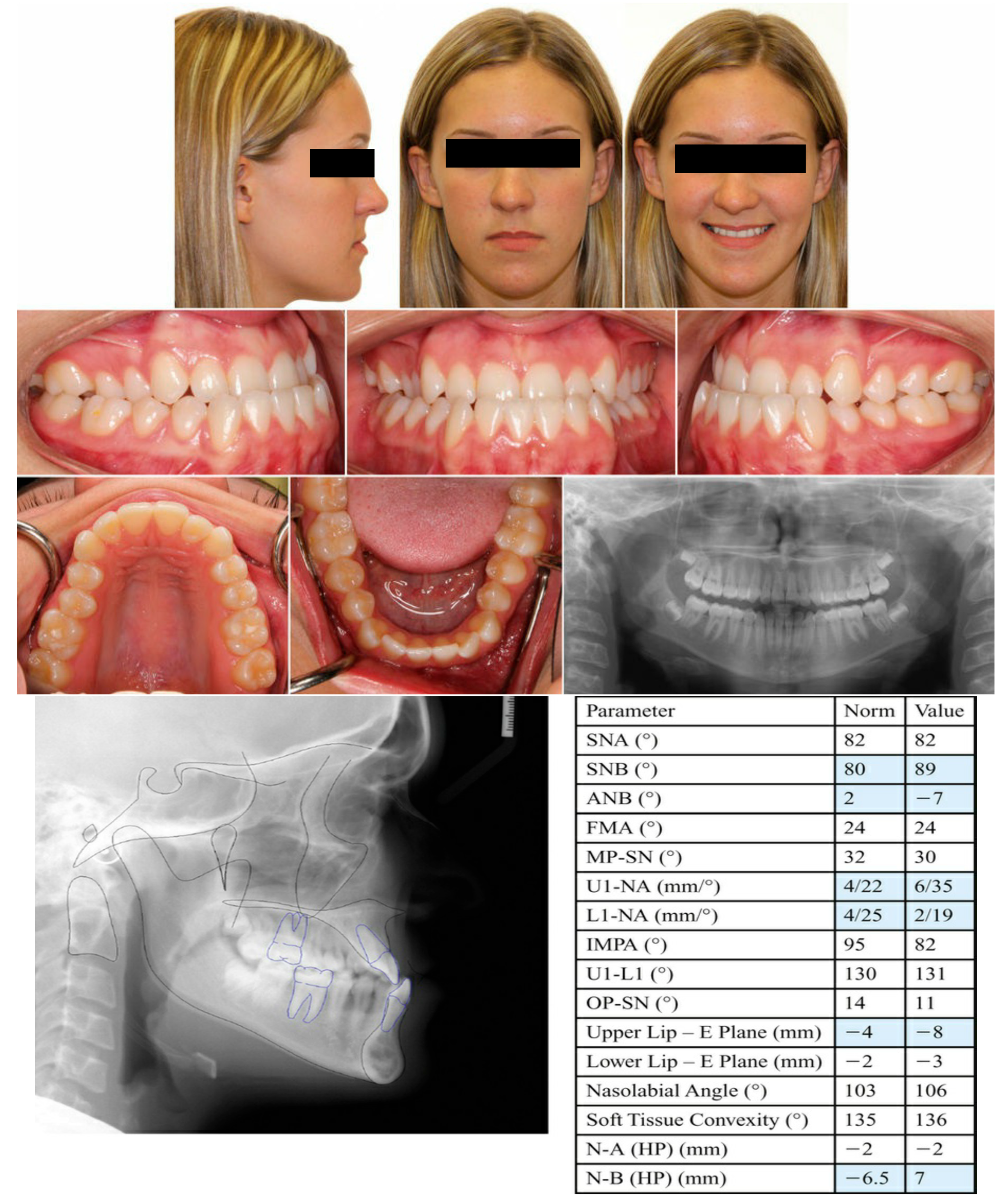

Appendix A.5. Case 5

| Age | 17 years | Over Jet = −3 mm |

| Sex | Female | Over bite = 3 mm |

| Breathing | Nasal |

References

- Asgari, I.; Soltani, S.; Sadeghi, S.M. Effects of iron products on decay, tooth microhardness, and dental discoloration: A systematic review. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 11, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Feng, Y.; Guo, H.G.; Liu, B.W.; Zhang, Y. Consequences of orthodontic treatment in malocclusion patients: Clinical and microbial effects in adults and children. BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiyak, H.A. Does orthodontic treatment affect patients’ quality of life? J. Dent. Educ. 2008, 72, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estai, M.; Kanagasingam, Y.; Xiao, D.; Vignarajan, J.; Huang, B.; Kruger, E.; Tennant, M. A proof-of-concept evaluation of a cloud-based store-and-forward telemedicine app for screening for oral diseases. J. Telemed. Telecare 2016, 22, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.K.; Kerr, W.J. Orthodontics in general dental practice. A survey of attitudes in Glasgow. Br. Dent. J. 1985, 159, 344–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bondt, B.; Aartman, I.H.; Zentner, A. Referral patterns of Dutch general dental practitioners to orthodontic specialists. Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 32, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; McComb, J.L.; Fox, N.; Bearn, D.; Wright, J. Do dentists refer orthodontic patients inappropriately? Br. Dent. J. 1996, 181, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koochek, A.R.; Yeh, M.S.; Rolfe, B.; Richmond, S. The relationship between Index of Complexity, Outcome and Need, and patients’ perceptions of malocclusion: A study in general dental practice. Br. Dent. J. 2001, 191, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Shaw, W. Preliminary evaluation of an illustrated scale for rating dental attractiveness. Eur. J. Orthod. 1987, 9, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, J.; Cons, N.C. Comparing and contrasting two orthodontic indices, the Index of Orthodontic Treatment need and the Dental Aesthetic Index. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1996, 110, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, W.P.; O’Brien, K.D.; Stephens, C.D. Orthodontic teaching practice and undergraduate knowledge in British dental schools. Br. Dent. J. 2002, 192, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Miguel, J.A.; Canavarro, C.; Ferreira, J.D.; Brunharo, I.H.; Almeida, M.A. Class-III malocclusion diagnosis by graduation students. Rev. Dent. Press Ortod. Ortop. Facial 2008, 13, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavarro, C.; Miguel, J.A.M.; Quintão, C.C.A.; Torres, M.F.M.; Ferreira, J.P.M.; Brunharo, I.H.V.P. Assessment of the orthodontic knowledge demonstrated by dental school undergraduates: Recognizing the key features of Angle Class II, Division 1 malocclusion. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2012, 17, 52.e1–52.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shahrani, I. Diagnosis and referral of orthodontic cases: An institutional survey among dental graduates. World J. Dent. 2014, 5, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatani, E.J.; Hassanain, Y.J.; AlTuraifi, S.H.; AlGhamdi, W.; AlNasser, M.H.; AliAlnahwi, A.; AlSaeed, Z.A. Undergraduate knowledge in diagnosing orthodontic problems in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Compr. Adv. Pharmacol. 2019, 4, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sobouti, F.; Alizadeh-Navaei, R.; Armin, M.; Lotfizadeh, A.; Aryana, M.; Dadgar, S. Evaluating general dental practitioners’ knowledge about appropriate timing of orthodontic treatment in the north of Iran. Iran. J. Orthod. 2020, 15, e117781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohra, S.; Malik, A.M.H. Knowledge skill and attitude among fresh dental graduates about orthodontics. Health Prof. Educ. J. 2020, 3, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, H.N.; Ozbilen, E.O.; Karabiber, G. Assessment of the diagnostic skills of general dentists in different types of orthodontic malocclusions. Turk. J. Orthod. 2021, 34, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, S.D.; Alshawy, E.S. Knowledge and perception of orthodontic treatment among undergraduate dental students in Qassim Region. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 5, 2143–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, B.B.; Sokmen, T.; Celik, B.; Tortop, T. Perception of dental students towards case-based orthodontic education. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2022, 83 (Suppl. S1), 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayalar, E.; Erdoğan, P.; Güneş, R. Orthodontic diagnosis, treatment and consultation approaches of general dental practitioners: A cross-sectional Study. Turk. Klin. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 29, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandana, B.; Vineesha, C.M.; Simhadri, G.; Pitta, N.; Kundana, D. Identification of malocclusion by dental undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2023, 17, ZC34–ZC39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, A.; Ur Rehman, A.; Ibnerasa, S.; Glanville, R.; Ali, K. Case-based learning in undergraduate orthodontic education: A cross sectional study. MedEdPublish (2016) 2024, 14, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Kadhom, Z.M.; Hassan, A.F.A.; Kadhum, H.I.; Nahidh, M.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Russo, D.; Cicciù , M.; Minervini, G. Awareness to orthodontics among a sample of final year dental students. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2025, 14, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.; Alexander, S.A. Atlas of Orthodontic Case Review, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, R.; Uribe, F.A. Atlas of Complex Orthodontics, 1st ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, R.A.; Jedrychowski, J. Self-assessed clinical competence: A comparison between students in an advanced dental education elective and in the general clinic. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2002, 6, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, A.; Dalaie, K.; Behnaz, M. Investigating the desire of last year dental students towards conducting orthodontic treatments in their future profession. J. Craniomaxillofac. Res. 2023, 10, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.M.; Abdulrahman, A.A.; Ibrahim, A.I. Evaluation of dental students and alumni’s confidence level in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment-planning: A qualitative study. J. Dent. Educ. 2025, 89, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Shah, H.; Raza, S.Z. Evaluation of development of clinical reasoning skills in dental students through diagnostic thinking inventory. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2023, 73, 1843–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, S.; Abu Alhaija, E.; Ali, K. Orthodontic curricula in undergraduate dental education—A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Popat, H.; Johnson, I.G. Dental students’ experiences of treating orthodontic emergencies—A qualitative assessment of student reflections. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2016, 20, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questions | Answers | Case No. 1 Class III Face Mask Treatment | Case No. 2 Class II Camouflage Treatment | Case No. 3 Class I | Case No. 4 Class II Camouflage Treatment | Case No. 5 Class III Orthognathic Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Need orthodontic treatment | 137 (83%) | 120 (73%) | 151 (92%) | 147 (89%) | 159 (96%) |

| No need for orthodontic treatment | 28 (17%) | 45 (27%) | 14 (8%) | 18 (11%) | 6 (4%) | |

| p-value | ≤0.001 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.001 | |

| Q2 | Need orthognathic surgery | 9 (7%) | 13 (11%) | 22 (15%) | 23 (16%) | 126 (79%) |

| No need for orthognathic surgery | 128 (93%) | 107 (89%) | 129 (85%) | 124 (84%) | 33 (21%) | |

| p-value | ≤0.001 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.001 | |

| Q3 | Unesthetic profile and irregular teeth | 9 (100%) | 11 (85%) | 17 (77%) | 23 (100%) | 124 (98%) |

| Irregular teeth | 0 (0%) | 2 (15%) | 5 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | |

| p-value | - | 0.022 | 0.017 | - | ≤0.001 | |

| Q4 | Protruded mandible | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 101 (81%) |

| Retruded mandible | 8 (89%) | 3 (27%) | 5 (29%) | 6 (26%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Protruded Maxilla | 0 (0%) | 8 (73%) | 12 (71%) | 16 (70%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Retruded Maxilla | 1 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 23 (19%) | |

| p-value | 0.039 | 0.277 | 0.143 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abbass, N.N.; Kadhom, Z.M.; Al-Lehaibi, W.K.; Nahidh, M. Evaluating the Diagnostic Proficiency Among a Sample of Final Stage Dental Students in Some Orthodontic Cases: A Comprehensive Analysis of Clinical Competence. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070300

Abbass NN, Kadhom ZM, Al-Lehaibi WK, Nahidh M. Evaluating the Diagnostic Proficiency Among a Sample of Final Stage Dental Students in Some Orthodontic Cases: A Comprehensive Analysis of Clinical Competence. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(7):300. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070300

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbass, Noor Nourie, Zainab Mousa Kadhom, Wurood Khairallah Al-Lehaibi, and Mohammed Nahidh. 2025. "Evaluating the Diagnostic Proficiency Among a Sample of Final Stage Dental Students in Some Orthodontic Cases: A Comprehensive Analysis of Clinical Competence" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 7: 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070300

APA StyleAbbass, N. N., Kadhom, Z. M., Al-Lehaibi, W. K., & Nahidh, M. (2025). Evaluating the Diagnostic Proficiency Among a Sample of Final Stage Dental Students in Some Orthodontic Cases: A Comprehensive Analysis of Clinical Competence. Dentistry Journal, 13(7), 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070300