Evaluation of the Quality and Educational Value of YouTube Videos on Class IV Resin Composite Restorations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size and Search Strategy

2.2. Video Analysis and Evaluation

- (1)

- YouTube™ videos were classified into three categories: educational, layperson, and commercial, which include supply companies or dental manufacturing.

- (2)

- The overall quality of the videos was evaluated using the ‘Video Information and Quality Index’ (VIQI) (Table 1). The VIQI index uses a 5-point rating scale, ranging from high quality (5) to poor (1), to evaluate different aspects of the videos. These aspects involve quality, accuracy, and information flow. One point is awarded for interviews with experts in the field, use of animation, a summary report, and video captions. Additionally, precision is evaluated by evaluating the coherence between the content and the video title.

- (3)

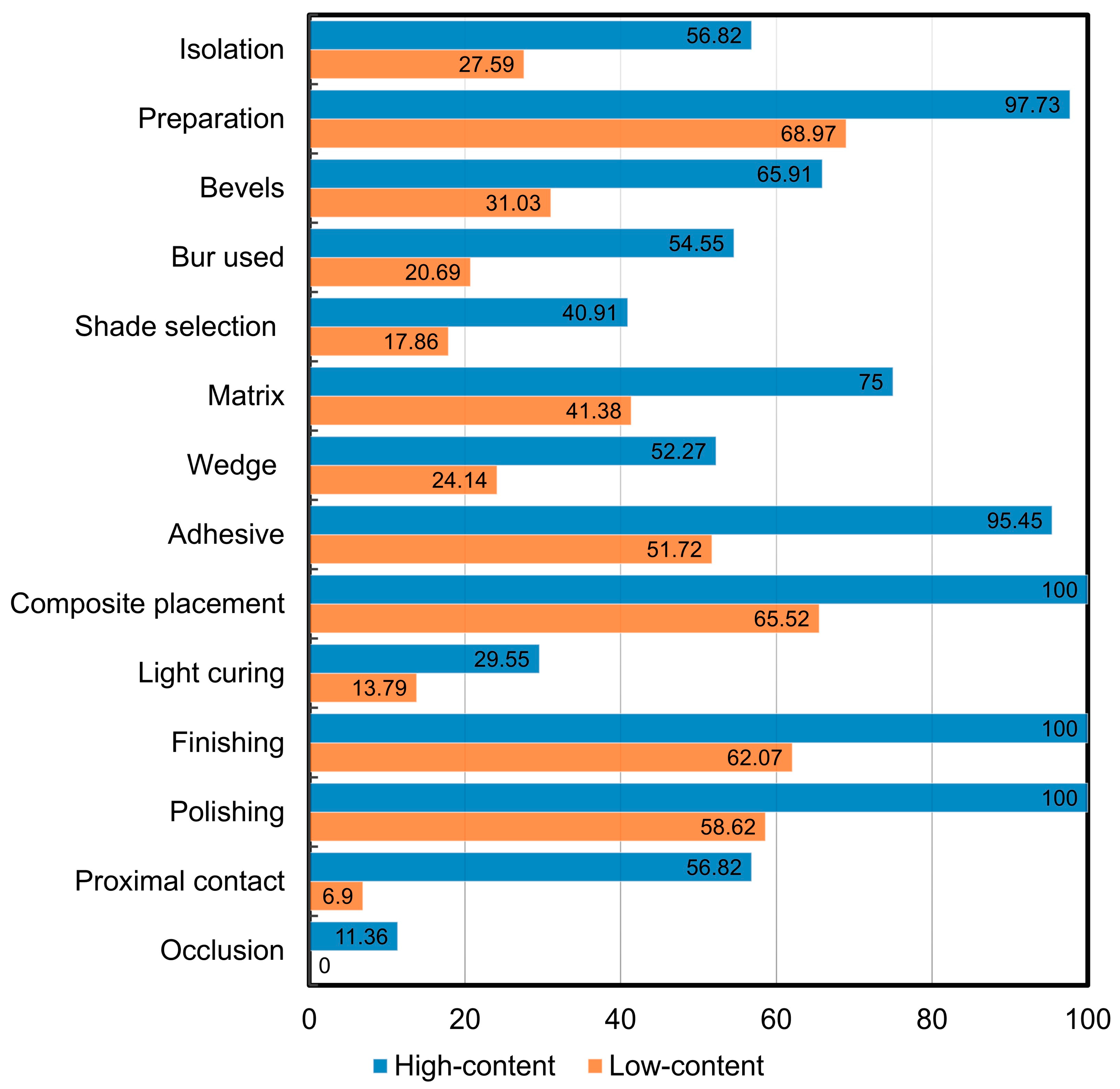

- In addition to the VIQI score, the quality of the YouTube™ videos was evaluated using specific standards associated with Class IV composite restorations. These criteria, which are detailed in Table 2, are derived from the textbook Modern Operative Dentistry [23]. The total scoring system comprises 13 points, with each criterion contributing 1 point. The average score was computed to assess the content value of the reviewed videos. Videos that met or exceeded the average score were classified as high-content, whereas those falling below the average were labeled as low-content.

- (4)

- In this study, the educational value of each video was defined as a combined measure that merged both the quality of instructional delivery and technical accuracy. Instructional quality was evaluated using the Video Information and Quality Index (VIQI) as outlined in Table 1. In addition, technical accuracy was assessed using specific content criteria derived from Modern Operative Dentistry (Table 2), encompassing key procedural steps including isolation, tooth preparation, and restorative techniques. Videos that demonstrated high performance in both technical and instructional aspects were considered to have high educational value.

- (5)

- The level of viewer interaction with the videos was assessed using a specific formula to calculate the viewing rate. This method entails dividing the total number of views by the number of days since the video was uploaded and multiplying that quotient by 100 [10].

| Aspect | 1 Point | 2 Points | 3 Points | 4 Points | 5 Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow of information | Disjointed; difficult to follow | Partially disorganized; flow needs improvement | Reasonably organized; some flow issues | Well-organized; easy to follow | Seamless flow; logically structured and engaging |

| Accuracy | Frequent inaccuracies; misleading information | Some inaccuracies; questionable content | Generally accurate; minor inaccuracies | Mostly accurate; reliable information | Highly accurate; thoroughly verified. |

| Quality | Poor production; distracting elements | Low quality; noticeable issues present | Average quality; some minor distractions | Good quality; few distractions | Excellent quality; professionally produced |

| Precision | Extremely vague; no relevant details | Some relevant details, but mostly unclear | Moderately clear; some useful details | Generally clear; most details relevant | Highly precise; all details relevant and clear |

| # | Criteria | =1 | =0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Isolation | Demonstrate proper isolation method used. Proper isolation method is defined as complete tooth isolation using a rubber dam, with appropriate clamp selection and a secure seal. | Did not demonstrate proper isolation or used incorrect method. |

| 2 | Tooth preparation | Demonstrate accurate tooth preparation guidelines based on Modern Operative Dentistry (proximal clearance, removal of unsupported enamel, no remaining caries, occlusal wall convergence, 90-degree margins). | Did not demonstrate accurate tooth preparation guidelines. |

| 3 | Bevels | Demonstrate correct bevel application. | Did not demonstrate correct bevel application, or no bevel used. |

| 4 | Bur used | Demonstrate a clear rationale for bur selection during tooth preparation, specifying the type and shape used at each step. | Did not demonstrate appropriate bur selection or none used. |

| 5 | Matrix application | Demonstrate correct matrix applied for restoration. | Did not demonstrate correct matrix application or none used. |

| 6 | Wedge application | Demonstrate correct wedge direction for proper adaptation. | Did not demonstrate correct wedge direction or none used. |

| 7 | Adhesive placement technique used | Demonstrate proper adhesive technique. | Did not demonstrate proper adhesive technique or none used. |

| 8 | Composite insertion technique | Demonstrate correct composite insertion technique. | Did not demonstrate correct composite insertion technique. |

| 9 | Light curing angulation and time | Demonstrate correct curing time and angle for effective polymerization. | Did not demonstrate correct curing time or angle. |

| 10 | Finishing of resin composite | Demonstrate proper finishing tools used for optimal restoration. | Did not demonstrate proper finishing tools or none used. |

| 11 | Polishing of resin composite | Demonstrate correct polishing method for restoration. | Did not demonstrate correct polishing method or none performed. |

| 12 | Proximal contact | Demonstrate correct contact established for proximal surfaces. | Did not demonstrate correct contact establishment. |

| 13 | Occlusion | Demonstrate correct occlusion check and adjustment. | Did not demonstrate correct occlusion check or adjustment. |

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Correa, M.B.; Peres, M.A.; Peres, K.G.; Horta, B.L.; Barros, A.D.; Demarco, F.F. Amalgam or Composite Resin? Factors Influencing the Choice of Restorative Material. J. Dent. 2012, 40, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rho, Y.-J.; Namgung, C.; Jin, B.-H.; Lim, B.-S.; Cho, B.-H. Longevity of Direct Restorations in Stress-Bearing Posterior Cavities: A Retrospective Study. Oper. Dent. 2013, 38, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreshaid, L.; El-Badrawy, W.; Lawrence, H.P.; Santos, M.J.; Prakki, A. Composite versus Amalgam Restorations Placed in Canadian Dental Schools. Oper. Dent. 2021, 46, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alreshaid, L.; El-Badrawy, W.; Kulkarni, G.; Santos, M.J.; Prakki, A. Resin Composite Versus Amalgam Restorations Placed in United States Dental Schools. Oper. Dent. 2023, 48, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balhaddad, A.A.; AlGhamdi, N.; Alqahtani, M.; Alsulaiman, O.A.; Alshammari, A.; Farraj, M.J.; Alsulaiman, A.A. Predictors of Procedural Errors in Class II Resin Composite Restorations Using Bitewing Radiographs. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerbashi, J.; Alkhubaizi, Q.; Parsa, A.; Shabayek, M.; Strassler, H.; Melo, M.A.S. Prevalence and Characteristics of Radiographic Radiolucencies Associated with Class II Composite Restorations. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, I.R.; Lynch, C.D.; Wilson, N.H. Factors Influencing Repair of Dental Restorations with Resin Composite. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2014, 6, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akakpo, M.G.; Akakpo, P.K. Recognizing the Role of YouTube in Medical Education. Discov. Educ. 2024, 3, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakin, M.; Linden, K. Adaptive E-Learning Platforms Can Improve Student Performance and Engagement in Dental Education. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.Y.; Gao, X.; Wong, K.; Tse, C.S.K.; Chan, Y.Y. Learning Clinical Procedures Through Internet Digital Objects: Experience of Undergraduate Students Across Clinical Faculties. JMIR Med. Educ. 2015, 1, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, I.; Yarwood-Ross, L.; Haigh, C. YouTube as a Source of Clinical Skills Education. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 1576–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Kruger, E.; Tennant, M. YouTube: A New Way of Supplementing Traditional Methods in Dental Education. J. Dent. Educ. 2014, 78, 1568–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.E.; Abbassi, E.; Qian, X.; Mecham, A.; Simeteys, P.; Mays, K.A. YouTube Use among Dental Students for Learning Clinical Procedures: A Multi-Institutional Study. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 84, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, E.H.; Ghazal, S.S.; Alshehri, R.D.; Albisher, H.N.; Albishri, R.S.; Balhaddad, A.A. Navigating the Practical-Knowledge Gap in Deep Margin Elevation: A Step towards a Structured Case Selection—A Review. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, E.H.; Paravina, R.D. Color Adjustment Potential of Resin Composites: Optical Illusion or Physical Reality, a Comprehensive Overview. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, W.A.; Fahl, N. Nature-Mimicking Layering with Composite Resins through a Bio-Inspired Analysis: 25 Years of the Polychromatic Technique. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2023, 35, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Yang, K.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Liu, F. Step-by-Step Teaching Method: Improving Learning Outcomes of Undergraduate Dental Students in Layering Techniques for Direct Composite Resin Restorations. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhaddad, A.A.; Alkhalifah, I.; Albuhmdouh, D.; AlSheikh, R.; Al Dehailan, L.; AlQuorain, H.; Alsulaiman, A.A. Assessment of Quality and Reliability of YouTube Videos for Student Learning on Class II Resin Composite Restorations. Oper. Dent. 2025, 50, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, W.; Mohamed, F.; Elhassan, M.; Shoufan, A. Is YouTube a Reliable Source of Health-Related Information? A Systematic Review. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, V.; Simmons, K.; Matthews, L.; Fleet, L.; Gustafson, D.L.; Fairbridge, N.A.; Xu, X. YouTube as an Educational Resource in Medical Education: A Scoping Review. Med. Sci. Educ. 2020, 30, 1775–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nason, K.; Donnelly, A.; Duncan, H.F. YouTube as a Patient-Information Source for Root Canal Treatment. Int. Endod. J. 2016, 49, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegarty, E.; Campbell, C.; Grammatopoulos, E.; DiBiase, A.T.; Sherriff, M.; Cobourne, M.T. YouTubeTM as an Information Resource for Orthognathic Surgery. J. Orthod. 2017, 44, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, C.R.G. (Ed.) Modern Operative Dentistry: Principles for Clinical Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasamnis, A.A.; Patil, S.S. YouTube as a Tool for Health Education. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzer, H.; Ismail, N.H.; Alsoleihat, F. Blended Learning with Video Demonstrations Enhances Dental Students’ Achievements in Tooth Carving. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2023, 14, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, S.; John, V.; Blanchard, S.; Eckert, G.J.; Hamada, Y. Assessing Effectiveness of an Audiovisual Educational Tool for Improving Dental Students’ Probing Depth Consistency. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 83, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulaiman, A.A.; Alsulaiman, O.A.; Alkhateeb, R.I.; AlMuhaish, L.; Alghamdi, M.; Nassar, E.A.; Almasoud, N.N. Orthodontic Elastics: A Multivariable Analysis of YouTubeTM Videos. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2024, 16, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Seo, M.-S. Assessment of Reliability and Information Quality of YouTube Videos about Root Canal Treatment after 2016. BMC Oral. Health 2022, 22, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y.R.; Shiraguppi, V.L.; Deosarkar, B.A.; Shelke, U.R. Long-Term Survival and Reasons for Failure in Direct Anterior Composite Restorations: A Systematic Review. J. Conserv. Dent. 2021, 24, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintze, S.D.; Rousson, V.; Hickel, R. Clinical Effectiveness of Direct Anterior Restorations—A Meta-Analysis. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, F.R.R.; Romano, A.R.; Lund, R.G.; Piva, E.; Rodrigues Júnior, S.A.; Demarco, F.F. Three-Year Clinical Performance of Composite Restorations Placed by Undergraduate Dental Students. Braz. Dent. J. 2011, 22, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, J.M.; Chaves, V.C.V.; Risso, P.A.; Magno, M.B.; Maia, L.C.; Pithon, M.d.M. YouTubeTM as a Source of Tooth Avulsion Information: A Video Analysis Study. Dent. Traumatol. 2023, 39, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzel, İ.; Ghabchi, B.; Akalın, A.; Eden, E. YouTube as an Information Source in Paediatric Dentistry Education: Reliability and Quality Analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, S.R.; Khan, A.S.; Ali, M.; Abutheraa, E.A.; Khaled Alkhrayef, A.; Aljibrin, F.J.; Almutairi, N.S. An Evaluation of the Usefulness of YouTube® Videos on Crown Preparation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1897705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaikwad, A.; Rachh, P.; Raut, K. Critical Evaluation of YouTube Videos Regarding the All-on-4 Dental Implant Treatment Concept: A Content-Quality Analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezner, S.K.; Hodgman, E.I.; Diesen, D.L.; Clayton, J.T.; Minkes, R.K.; Langer, J.C.; Chen, L.E. Pediatric Surgery on YouTubeTM: Is the Truth out There? J. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 49, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, P.L.; Wason, S.; Stern, J.M.; Deters, L.; Kowal, B.; Seigne, J. YouTube as Source of Prostate Cancer Information. Urology 2010, 75, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, U.; Klotz, C. Personalized Feedback in Digital Learning Environments: Classification Framework and Literature Review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knösel, M.; Jung, K.; Bleckmann, A. YouTube, Dentistry, and Dental Education. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 75, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Seo, H.S.; Hong, T.H. YouTube as a Source of Patient Information on Gallstone Disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 4066–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavan, M.A.; Gökçe, G. YouTube as a Source of Information on Adult Orthodontics: A Video Analysis Study. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2022, 11, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Views | 7 | 1,539,671 | 49,568.48 | 194,481.80 |

| Number of Likes | 0 | 29,000 | 942.6438 | 3665.56 |

| Duration (min) | 0.18 | 568 | 37.56 | 96.10 |

| Days Since Upload | 93 | 4492 | 1791.03 | 1003.67 |

| Viewing Rate | 0.63 | 34,660.77 | 2159.92 | 6232.02 |

| Interaction Index | 0 | 1504.04 | 40.70 | 223.54 |

| Number of Subscribers | 0 | 704,000 | 55,599.45 | 146,716.90 |

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow | 1 | 5 | 3.75 | 0.91 |

| Accuracy | 1 | 5 | 3.67 | 0.97 |

| Quality | 1 | 5 | 3.47 | 1.13 |

| Precision | 1 | 5 | 3.64 | 1.05 |

| VIQI score | 4 | 20 | 14.53 | 3.48 |

| Content Score | 1 | 12 | 7.59 | 2.74 |

| Variable | High-Content Videos (n = 44) | Low-Content Videos (n = 29) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Number of Views | 73,549.96 | 248,001.10 | 13,182.79 | 23,047.51 | 0.20 |

| Number of Likes | 1382.30 | 4664.04 | 275.59 | 615.74 | 0.21 |

| Duration (min) | 44.49 | 116.07 | 27.05 | 53.56 | 0.45 |

| Days Since Upload | 1887.36 | 1080.93 | 1644.86 | 871.37 | 0.32 |

| Viewing Rate | 2995.11 | 7842.89 | 892.76 | 1626.99 | 0.16 |

| Interaction Index | 65.63 | 286.46 | 2.88 | 4.27 | 0.24 |

| Number of Subscribers | 65,867.17 | 159,377.50 | 40,374.90 | 126,805.50 | 0.47 |

| Variable | High-Content Videos (n = 44) | Low-Content Videos (n = 29) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Video source | |||

| Commercial | 15.91% (7) | 17.24% (5) | 0.584 |

| Dentist | 72.73% (32) | 79.31% (23) | |

| Layperson | 11.36% (5) | 3.45% (1) | |

| Type of account | |||

| Commercial | 11.36% (5) | 10.34% (3) | 0.991 |

| Educational | 75.00% (33) | 75.86% (22) | |

| Personal | 13.64% (6) | 13.79% (4) |

| Variable | High-Content Videos (n = 44) | Low-Content Videos (n = 29) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Flow | 4.11 | 0.65 | 3.21 | 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| Accuracy | 4.07 | 0.82 | 3.07 | 0.88 | <0.0001 |

| Quality | 4 | 0.86 | 2.66 | 1.01 | <0.0001 |

| Precision | 4.16 | 0.81 | 2.86 | 0.88 | <0.0001 |

| VIQI score | 16.34 | 2.46 | 11.79 | 2.96 | <0.0001 |

| Content Score | 9.36 | 1.33 | 4.90 | 2.04 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

AlSahafi, R.A.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Alkhalifah, I.; Albuhmdouh, D.; Farraj, M.J.; Alhussein, A.; Balhaddad, A.A. Evaluation of the Quality and Educational Value of YouTube Videos on Class IV Resin Composite Restorations. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070298

AlSahafi RA, Alhazmi HA, Alkhalifah I, Albuhmdouh D, Farraj MJ, Alhussein A, Balhaddad AA. Evaluation of the Quality and Educational Value of YouTube Videos on Class IV Resin Composite Restorations. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(7):298. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070298

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlSahafi, Rashed A., Hesham A. Alhazmi, Israa Alkhalifah, Danah Albuhmdouh, Malik J. Farraj, Abdullah Alhussein, and Abdulrahman A. Balhaddad. 2025. "Evaluation of the Quality and Educational Value of YouTube Videos on Class IV Resin Composite Restorations" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 7: 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070298

APA StyleAlSahafi, R. A., Alhazmi, H. A., Alkhalifah, I., Albuhmdouh, D., Farraj, M. J., Alhussein, A., & Balhaddad, A. A. (2025). Evaluation of the Quality and Educational Value of YouTube Videos on Class IV Resin Composite Restorations. Dentistry Journal, 13(7), 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13070298