Impact of Bone Grafts Containing Metformin on Implant Surface Hydrophilicity: An In Vitro Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- 1.

- Ti-alloy–Machined disk (myplant GmbH, Neuss, Germany);

- 2.

- Ti-sandblasted and acid-etched surface (SLA) disk–(myplant GmbH, Neuss, Germany);

- 3.

- Zirconia (SDS®, Swiss Dental Solutions, Kreuzlingen, Germany)

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Kong, L.; Liu, P. Mechanical and Biological Properties of Titanium and Its Alloys for Oral Implant with Preparation Techniques: A Review. Materials 2023, 16, 6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apratim, A.; Eachempati, P.; Krishnappa Salian, K.K.; Singh, V.; Chhabra, S.; Shah, S. Zirconia in dental implantology: A review. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.P.; Cao, N.J.; Zhu, Y.H.; Wang, W. The osseointegration and stability of dental implants with different surface treatments in animal models: A network meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Mao, Z.; Gao, C. Surface modification and property analysis of biomedical polymers used for tissue engineering. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2007, 60, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyan, B.D.; Lotz, E.M.; Schwartz, Z. Roughness and Hydrophilicity as Osteogenic Biomimetic Surface Properties. Tissue Eng. Part A 2017, 23, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohana, D.; Anderson, N.K.; Delgado-Ruiz, R.; Romanos, G.E. Changes in implant surface characteristics and wettability induced by smoking in vitro: A preliminary investigation. Materials 2025, 18, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Sadiq, M.S.; Najeeb, S.; Khurshid, Z.; Zafar, M.S.; Heboyan, A. Effects of metformin on the bioactivity and osseointegration of dental implants: A systematic review. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2022, 18, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rena, G.; Hardie, D.G.; Pearson, E.R. The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christman, A.L.; Selvin, E.; Margolis, D.J.; Lazarus, G.S.; Garza, L.A. Hemoglobin A1c predicts healing rate in diabetic wounds. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 2121–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Salvatierra, A.; Calvo-Guirado, J.L.; González-Jaranay, M.; Moreu, G.; Delgado-Ruiz, R.A.; Gómez-Moreno, G. Peri-implant evaluation of immediately loaded implants placed in esthetic zone in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2: A two-year study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2016, 27, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Tao, Y.; Deng, Y.; Yu, J.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, G. Metformin accelerates wound healing in type 2 diabetic db/db mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 8691–8698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, A.R.; Rao, N.S.; Naik, S.B.; Kumari, M. Efficacy of Varying Concentrations of Subgingivally Delivered Metformin in the Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljofi, F.E.; Alesawy, A.; Alzaben, B.; Alshaikh, M.; Alotaibi, N.; Aldulaijan, H.A.; Alshehri, S.; Aljoghaiman, E.; Al-Dulaijan, Y.A.; AlSharief, M. Impact of Metformin on Periodontal and Peri-Implant Soft and Hard Tissue. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Vinitha, B.; Fathima, G. Bone grafts in dentistry. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2013, 5, S125–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, V.V.; Trinh, H.A.; Rokaya, D.; Trinh, D.H. Bone Augmentation for Implant Placement: Recent Advances. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 8900940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liñares, A.; Dopico, J.; Magrin, G.; Blanco, J. Critical review on bone grafting during immediate implant placement. Periodontology 2000 2023, 93, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, A.; Anderson, N.K.; Romanos, G.E. Bovine Mineral Grafting Affects the Hydrophilicity of Dental Implant Surfaces: An In Vitro Study. Materials 2024, 17, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvay, A.; Yli-Rantala, E.; Liu, C.H.; Peng, X.-H.; Koski, P.; Cindrella, L.; Kauranen, P.; Wilde, P.; Kannan, A. Characterization techniques for gas diffusion layers for proton exchange membrane fuel cells—A review. J. Power Sources 2012, 213, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, K.; Fu, S.; Cuiffo, M.; Simon, M.; Rafailovich, M.; Romanos, G.E. In vitro toxicity of bone graft materials to human mineralizing cells. Materials 2022, 15, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foretz, M.; Guigas, B.; Viollet, B. Metformin: From mechanisms of action to therapies. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skibiński, S.; Czechowska, J.P.; Guzik, M.; Vivcharenko, V.; Przekora, A.; Szymczak, P.; Zima, A. Scaffolds based on β-tricalcium phosphate and polyhydroxyalkanoates as biodegradable and bioactive bone substitutes with enhanced physicochemical properties. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 38, e00722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, H.H.K.; Dai, Z.; Yu, K.; Xiao, L.; Schneider, A.; Weir, M.D.; Oates, T.W.; Bai, Y.; et al. Effects of Metformin Delivery via Biomaterials on Bone and Dental Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; O-Hori, M.; Nakayama, K. Surface Roughness Measurement by Scanning Electron Microscope. CIRP Ann. 1982, 31, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

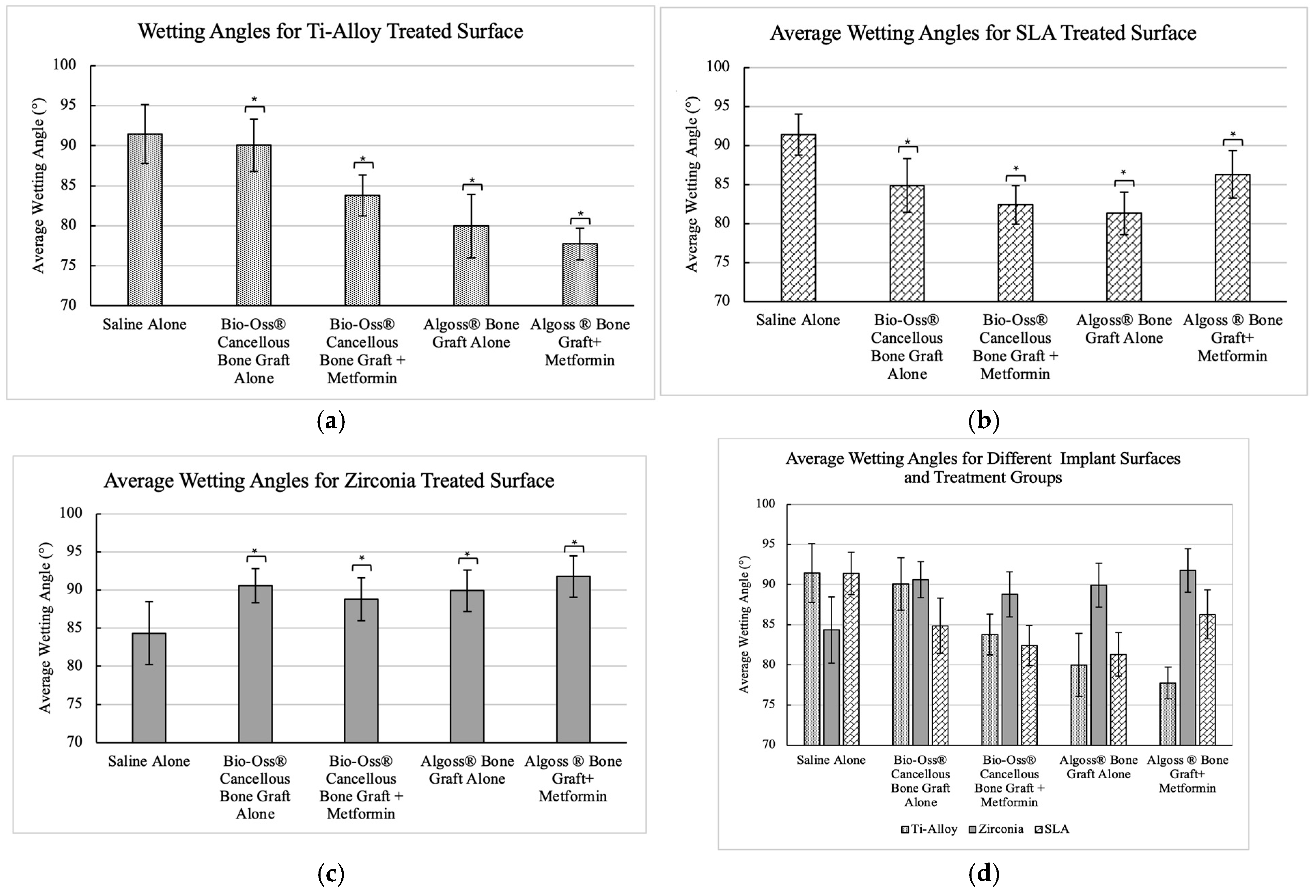

| Dental Implant Surface | Wetting Solution | N | Mean (°) | Std. Dev | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti-Alloy | Group A | 40 | 91.4 | 3.67 | [87.73, 95.07] |

| Group B | 40 | 90.1 | 3.27 | [86.83, 93.37] | |

| Group C | 40 | 83.8 | 2.55 | [81.25, 86.35] | |

| Group D | 40 | 79.9 | 3.94 | [75.96, 83.84] | |

| Group E | 40 | 77.7 | 1.98 | [75.72, 79.68] | |

| Ti-SLA | Group A | 40 | 91.4 | 2.63 | [88.77, 94.03] |

| Group B | 40 | 84.9 | 3.43 | [81.47, 88.33] | |

| Group C | 40 | 82.4 | 2.49 | [89.91, 84.89] | |

| Group D | 40 | 81.3 | 2.72 | [78.58, 84.02] | |

| Group E | 40 | 86.3 | 3.06 | [83.24, 89.36] | |

| Zirconia | Group A | 40 | 84.3 | 4.13 | [80.17, 88.43] |

| Group B | 40 | 90.6 | 2.24 | [88.36, 92.84] | |

| Group C | 40 | 88.8 | 2.83 | [85.97, 91.63] | |

| Group D | 40 | 89.9 | 2.73 | [87.17, 92.63] | |

| Group E | 40 | 91.8 | 2.70 | [89.10, 94.50] |

| (I) Group | (J) Group | Mean Diff. (I–J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | 1.35550 | 1.00074 | 1.000 | [−1.5207, 4.2317] |

| Group C | 7.65850 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [4.7823, 10.5347] | |

| Group D | 11.45900 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [8.5828, 14.3352] | |

| Group E | 13.71300 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [10.8368, 16.5892] | |

| Group B | Group A | −1.35550 | 1.00074 | 1.000 | [−4.2317, 1.5207] |

| Group C | 6.30300 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [3.4268, 9.1792] | |

| Group D | 10.10350 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [7.2273, 12.9797] | |

| Group E | 12.35750 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [9.4813, 15.2337] | |

| Group C | Group A | −7.65850 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [−10.5347, −4.7823] |

| Group B | −6.30300 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [−9.1792, −3.4268] | |

| Group D | 3.80050 | 1.00074 | 0.003 * | [0.9243, 6.6767] | |

| Group E | 6.05450 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [3.1783, 8.9307] | |

| Group D | Group A | −11.45900 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [14.3352, −8.5828] |

| Group B | −10.10350 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [−12.9797, −7.2273] | |

| Group C | −3.80050 | 1.00074 | 0.003 * | [−6.6767, −0.9243] | |

| Group E | 2.25400 | 1.00074 | 0.266 | [−0.6222, 5.1302] | |

| Group E | Group A | −13.71300 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [−16.5892, −10.8368] |

| Group B | −12.35750 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [−15.2337, −9.4813] | |

| Group C | −6.05450 | 1.00074 | 0.000 * | [−8.9307, −3.1783] | |

| Group D | −2.25400 | 1.00074 | 0.266 | [−5.1302, 0.6222] |

| (I) Group | (J) Group | Mean Diff. (I–J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | 6.52900 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [3.9072, 9.1508] |

| Group C | 9.00950 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [6.3877, 11.6313] | |

| Group D | 10.0985 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [7.4767, 12.7203] | |

| Group E | 5.11400 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [2.4922, 7.7358] | |

| Group B | Group A | −6.52900 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [−9.1508, −3.9072] |

| Group C | 2.48050 | 0.91222 | 0.078 | [−0.1413, 5.1023] | |

| Group D | 3.56950 | 0.91222 | 0.002 * | [0.9477, 6.1913] | |

| Group E | −1.41500 | 0.91222 | 1.000 | [−4.0368, 1.2068] | |

| Group C | Group A | −9.00950 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [−11.6313, −6.3877] |

| Group B | −2.48050 | 0.91222 | 0.078 | [−5.1023, 0.1413] | |

| Group D | 1.08900 | 0.91222 | 1.000 | [−1.5328, 3.7108] | |

| Group E | −3.89550 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [−6.5173, −1.2737] | |

| Group D | Group A | −10.09850 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [−12.7203, −7.4767] |

| Group B | −3.56950 | 0.91222 | 0.002 * | [−6.1913, −0.9477] | |

| Group C | −1.08900 | 0.91222 | 1.000 | [−3.7108, 1.5328] | |

| Group E | −4.98450 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [−7.6063, −2.3627] | |

| Group E | Group A | −5.11400 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [−7.7358, −2.4922] |

| Group B | 1.41500 | 0.91222 | 1.000 | [−1.2068, 4.0368] | |

| Group C | 3.89550 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [1.2737, 6.5173] | |

| Group D | 4.98450 | 0.91222 | 0.000 * | [2.3627, 7.6063] |

| (I) Group | (J) Group | Mean Diff. (I–J) | Std. Error | Sig | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | −6.26200 | 0.94645 | 0.000 * | [−8.9822, −3.5418] |

| Group C | −4.43650 | 0.94645 | 0.000 * | [−7.1567, −1.7163] | |

| Group D | −5.58200 | 0.94645 | 0.000 * | [−8.3022, −2.8618] | |

| Group E | −7.42300 | 0.94645 | 0.000 * | [−10.1432, −4.7028] | |

| Group B | Group A | 6.26200 | 0.94645 | 0.000 * | [3.5418, 8.9822] |

| Group C | 1.82550 | 0.94645 | 0.567 | [−0.8947, 4.5457] | |

| Group D | 0.68000 | 0.94645 | 1.000 | [−2.0402, 3.4002] | |

| Group E | −1.16100 | 0.94645 | 1.000 | [−3.8812, 1.5592] | |

| Group C | Group A | 4.43650 | 0.94645 | 0.000 * | [1.7163, 7.1567] |

| Group B | −1.82550 | 0.94645 | 0.567 | [−4.5457, 0.8947] | |

| Group D | −1.14550 | 0.94645 | 1.000 | [−3.8657, 1.5747] | |

| Group E | −2.98650 | 0.94645 | 0.021 * | [−5.7067, −0.2663] | |

| Group D | Group A | 5.58200 | 0.94645 | 0.000 * | [2.8618, 8.3022] |

| Group B | −0.68000 | 0.94645 | 1.000 | [−3.4002, 2.0402] | |

| Group C | 1.14550 | 0.94645 | 1.000 | [−1.5747, 3.8657] | |

| Group E | −1.84100 | 0.94645 | 0.547 | [−4.5612, 0.8792] | |

| Group E | Group A | 7.42300 | 0.94645 | 0.000 * | [4.7028, 10.1432] |

| Group B | 1.16100 | 0.94645 | 1.000 | [−1.5592, 3.8812] | |

| Group C | 2.98650 | 0.94645 | 0.021 * | [0.2663, 5.7067] | |

| Group D | 1.84100 | 0.94645 | 0.547 | [−0.8792, 4.5612] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shah, R.M.; Anderson, N.; Delgado-Ruiz, R.; Romanos, G. Impact of Bone Grafts Containing Metformin on Implant Surface Hydrophilicity: An In Vitro Study. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120611

Shah RM, Anderson N, Delgado-Ruiz R, Romanos G. Impact of Bone Grafts Containing Metformin on Implant Surface Hydrophilicity: An In Vitro Study. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):611. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120611

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Rahul Minesh, Nina Anderson, Rafael Delgado-Ruiz, and Georgios Romanos. 2025. "Impact of Bone Grafts Containing Metformin on Implant Surface Hydrophilicity: An In Vitro Study" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120611

APA StyleShah, R. M., Anderson, N., Delgado-Ruiz, R., & Romanos, G. (2025). Impact of Bone Grafts Containing Metformin on Implant Surface Hydrophilicity: An In Vitro Study. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120611