Efficacy of UVC Radiation in Reducing Bacterial Load on Dental Office Surfaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Surface Characterization (Materials)

- -

- -

- Stainless-steel consumables table (AISI 304, mirror/matte finish)—Reflectivity: polished stainless steel reflects a portion of incident UVC, increasing irradiance in some directions but also producing specular reflections and potential shadow cancelation; smooth surfaces minimize micro-sheltering [14,15,16].

- -

Quantitative Surface Property Assessment

- -

- Surface Roughness (Ra): The arithmetic average of the absolute values of the profile height deviations from the mean line (Ra) was measured in triplicate on each material using a calibrated profilometer (Mitutoyo Surftest SJ-210). Measurements to quantify micro-topography that can create “micro-shadowing” effects were taken across the grain of the wood, along the lay of the metal, and across a flat area on the dental unit polymer.

- -

- Contact Angle: The static contact angle was measured in triplicate for each surface using the sessile drop method with a goniometer (KRÜSS DSA100) and 5 μL of deionized water. This measurement indicates the surface’s hydrophobicity, which influences how contaminants and water-based aerosols adhere, potentially affecting the UVC dose received by microorganisms.

- -

- Spectral Reflectance (254 nm): The percentage of 254 nm UVC light reflected by each surface was measured using a calibrated spectroradiometer with an integrating sphere accessory. This helps determine how material reflectivity (e.g., for the stainless steel) might enhance the germicidal dose via scattered radiation.

2.3. UVC Device and Dosimetry

- -

- 5 min (300 s): 90 × 300/1000 = 27 mJ/cm2

- -

- 10 min (600 s): 90 × 600/1000 = 54 mJ/cm2

- -

- Instrument: Solar Light PMA2100 Radiometer (Serial Number: 2024-A-7215), Solar Light Company, Inc., Glenside, PA, USA. Spectral range: 200–280 nm

- -

- Measurement resolution: ±1 µW/cm2

- -

- Calibration: Traceable to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and performed by them; most recent calibration performed on 25 March 2025. This calibration occurred one week before the experimental period.

- -

- Lamp type: Dual low-pressure mercury lamps (2 × 40 W)

- -

- Emission peak: 253.7 nm

- -

- Lamp height above samples: 50 cm

- -

- Irradiance at 50 cm: 90 µW/cm2 (mean of three measurements)

- -

- Operating hours at time of test: ~250 h

2.4. Sampling Protocol

2.5. Culture and Identification

2.6. Data Handling and Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Contamination

3.2. Reduction After UVC Exposure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Górny, R.L.; Gołofit-Szymczak, M.; Pawlak, A.; Ławniczek-Wałczyk, A.; Cyprowski, M.; Stobnicka-Kupiec, A.; Płocińska, M.; Kowalska, J. Effectiveness of UV-C radiation in inactivation of microorganisms on materials with different surface structures. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2024, 31, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, A.; Fiorini, V.; Zangani, A.; Faccioni, P.; Signoriello, A.; Albanese, M.; Lombardo, G. Topical Agents in Biofilm Disaggregation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, P.D.; Moter, A.; Devine, D.A. Dental Plaque Biofilms: Communities, Conflict and Control. Periodontol. 2000 2011, 55, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hammadi, S.; Al-Shehari, W.A.; Edrees, W.H.; Al-Kaf, A.G.; Pan, S. Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among Patients with Oral Infections in Sana’a City, Yemen. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutala, W.A.; Weber, D.J. Disinfection, Sterilization, and Antisepsis: Principles, Practices, Current Issues, New Research, and New Technologies. Am. J. Infect. Control 2019, 47S, A1–A2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, W. Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation Handbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baudart, C.; Briot, T. Ultraviolet C Decontamination Devices in a Hospital Pharmacy: An Evaluation of Their Contribution. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demeersseman, N.; Saegeman, V.; Cossey, V.; Devriese, H.; Schuermans, A. Shedding a Light on Ultraviolet-C Technologies in the Hospital Environment. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 132, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.K.; Mont, M.A. Comparative evaluation of contemporary ultraviolet-C disinfection technologies: UVCeed as a benchmark for smart, portable, and effective pathogen control. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2025, 20, Doc53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, G.; Pasqua, S.; Douradinha, B.; Monaco, F.; Di Bartolo, C.; Conaldi, P.G.; D’Apolito, D. Efficacy of Three Commercial Disinfectants in Reducing Microbial Surfaces’ Contaminations of Pharmaceuticals Hospital Facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, R.; Joshi, L.T.; McGinn, C. Hospital Surface Disinfection Using Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation Technology: A Review. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 2022, 9, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliney, D.H.; Stuck, B.E. A Need to Revise Human Exposure Limits for Ultraviolet UV-C Radiation. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, N.G. The History of Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation for Air Disinfection. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujundzic, E.; Matalkah, F.; Howard, C.J.; Hernandez, M.; Miller, S.L. UV Air Cleaners and Upper-Room Air Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation for Controlling Airborne Bacteria and Fungal Spores. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2006, 3, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masjoudi, M.; Mohseni, M.; Bolton, J.R. Sensitivity of bacteria, protozoa, viruses, and other microorganisms to ultraviolet radiation. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2021, 126, 126021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, R.; Colucci, M.E.; Coluccia, A.; Ibrahim, M.M.M.; Zoni, R.; Veronesi, L.; Affanni, P.; Pasquarella, C. An Overview on the Use of Ultraviolet Radiation to Disinfect Air and Surfaces. Acta Biomed. 2023, 94, e2023165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.-J.; Choi, Y.-S.; Seo, D.-G. Bactericidal Effects of Ultraviolet-C Light-Emitting Diode Prototype Device Through Thin Optical Fiber. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvam, E.; Benner, K. Mechanistic Insights into UV-A Mediated Bacterial Disinfection via Endogenous Photosensitizers. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2020, 209, 111899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imada, K.; Tanaka, S.; Ibaraki, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Ito, S. Antifungal Effect of 405-nm Light on Botrytis cinerea. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 59, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikelonis, A.M.; Abdel-Hady, A.; Aslett, D.; Ratliff, K.; Touati, A.; Archer, J.; Serre, S.; Mickelsen, L.; Taft, S.; Calfee, M.W. Comparison of Surface Sampling Methods for an Extended Duration Outdoor Biological Contamination Study. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setlow, B.; Korza, G.; Blatt, K.M.; Fey, J.P.; Setlow, P. Mechanism of Bacillus subtilis Spore Inactivation by and Resistance to Supercritical CO2 plus Peracetic Acid. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessling, M.; Haag, R.; Sieber, N.; Vatter, P. The Impact of Far-UVC Radiation (200–230 nm) on Pathogens, Cells, Skin, and Eyes—A Collection and Analysis of a Hundred Years of Data. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2021, 16, Doc07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öberg, R.; Sil, T.B.; Johansson, A.C.; Malyshev, D.; Landström, L.; Johansson, S.; Andersson, M.; Andersson, P.O. UV-Induced Spectral and Morphological Changes in Bacterial Spores for Inactivation Assessment. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadeh, F.; Geppert, A.; Jackson, L.J.; Harrison, J.J.; Achari, G. Hydrogen Peroxide Augments the Disinfection Efficacy of 280 nm Ultraviolet LEDs against Antibiotic-Resistant Uropathogenic Otherwise Tolerant to Germicidal Irradiation. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 29558–29568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Sarango, P.; Delgado-Armijos, N.; Romero-Martínez, L.; Cruz, D.; Pinos-Vélez, V. Advancing Waterborne Fungal Spore Control: UV-LED Disinfection Efficiency and Post-Treatment Reactivation Analysis. Water 2025, 17, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q. Effectiveness of ultraviolet-C disinfection systems for reduction of multi-drug resistant organism infections in healthcare settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2023, 151, e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.C.; Olsen, M.; Tronstad, O.; Fraser, J.F.; Goldsworthy, A.; Alghafri, R.; McKirdy, S.J.; Tajouri, L. Ultraviolet-C-based sanitization is a cost-effective option for hospitals to manage health care-associated infection risks from high touch mobile phones. Front. Health Serv. 2025, 4, 1448913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, T.; Gomes Filho, N.; Padrão, J.; Zille, A. A Comprehensive Analysis of the UVC LEDs’ Applications and Decontamination Capability. Materials 2022, 15, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, D.; Aquino de Muro, M.; Buonanno, M.; Brenner, D.J. Wavelength-Dependent DNA Photodamage in a 3-D Human Skin Model over the Far-UVC and Germicidal UVC Wavelength Ranges from 215 to 255 nm. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 98, 1167–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abushahba, F.; Algahawi, A.; Areid, N.; Vallittu, P.K.; Närhi, T. Efficacy of biofilm decontamination methods of dental implant surfaces: A systematic review of in vitro studies. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2025, 133, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E2197; Standard Quantitative Disk Carrier Test Method for Determining the Bactericidal, Mycobactericidal, Fungicidal, Sporicidal, and Virucidal Activities of Liquid Chemical Germicides. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Seneviratne, C.J.; Khan, S.A.; Zachar, J.; Yang, Z.; Kiran, R.; Walsh, L.J. Efficacy of Ultrasonic Cleaning Products with Various Disinfection Chemistries on Dental Instruments Contaminated with Bioburden. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 1632–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, S.; Feier, B.; Capatina, D.; Tertis, M.; Cristea, C.; Popa, A. An Overview of Healthcare Associated Infections and Their Detection Methods Caused by Pathogen Bacteria in Romania and Europe. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Galarde-López, M.; Cornejo-Juárez, P.; Carrillo-Quiroz, B.A.; Velázquez-Acosta, C.; Bobadilla-del-Valle, M.; Ponce-de-León, A.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus sp. and Enterococcus sp. in Municipal and Hospital Wastewater: A Longitudinal Study. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavifar, M.; Abdi, A.; Nikooee, E.; Aghili, O.; Riazi, M. Quantifying the Impact of Surface Roughness on Contact Angle Dynamics under Varying Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, R.A.; Navne, J.; Adelmark, M.V.; Shkondin, E.; Crovetto, A.; Hansen, O.; Bachmann, J.; Taboryski, R. Understanding the Light Induced Hydrophilicity of Metal-Oxide Thin Films. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.T.; Gourlay, T.; Maclean, M. The Antibacterial Efficacy of Far-UVC Light: A Combined-Method Study Exploring the Effects of Experimental and Bacterial Variables on Dose–Response. Pathogens 2024, 13, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duering, H.; Westerhoff, T.; Kipp, F.; Stein, C. Short-Wave Ultraviolet-Light-Based Disinfection of Surface Environment Using Light-Emitting Diodes: A New Approach to Prevent Health-Care-Associated Infections. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Surface | Porosity/Roughness | Typical UVC Reflectance (254 nm) | Likely Effect on Decontamination | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varnished oak (wood) | Moderate porosity; grain-aligned micro-crevices even after varnish | 5–12% (varies with coating thickness and pigment) | Absorption and “micro-shadowing” may protect cells lodged in pores or along fibers | [11,12,13] |

| Stainless steel (AISI 304) | Ra ≈ 0.05–0.2 µm (polished) | 25–30% | High reflectivity can enhance fluence on adjacent points; minimal micro-sheltering if free of debris | [14,15,16] |

| Dental-unit polymer/composite | Grooves and seams; matte areas | <8% (most plastics); varies by pigment | Absorption and irregular topology reduce direct fluence; seams may shield bacteria | [17,18,19] |

| Material | Roughness (Ra) | Static Contact Angle | Spectral Reflectance (254 nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wood (Varnished Oak) | 1.5 ± 0.2 μm | 68.4° ± 2.5° | 7.2% ± 0.4% |

| Stainless Steel (AISI 304) | 0.08 ± 0.01 μm | 83.6° ± 1.8° | 28.5% ± 1.2% |

| Dental Unit Polymer | 0.9 ± 0.1 μm | 76.2° ± 3.1° | 5.1% ± 0.3% |

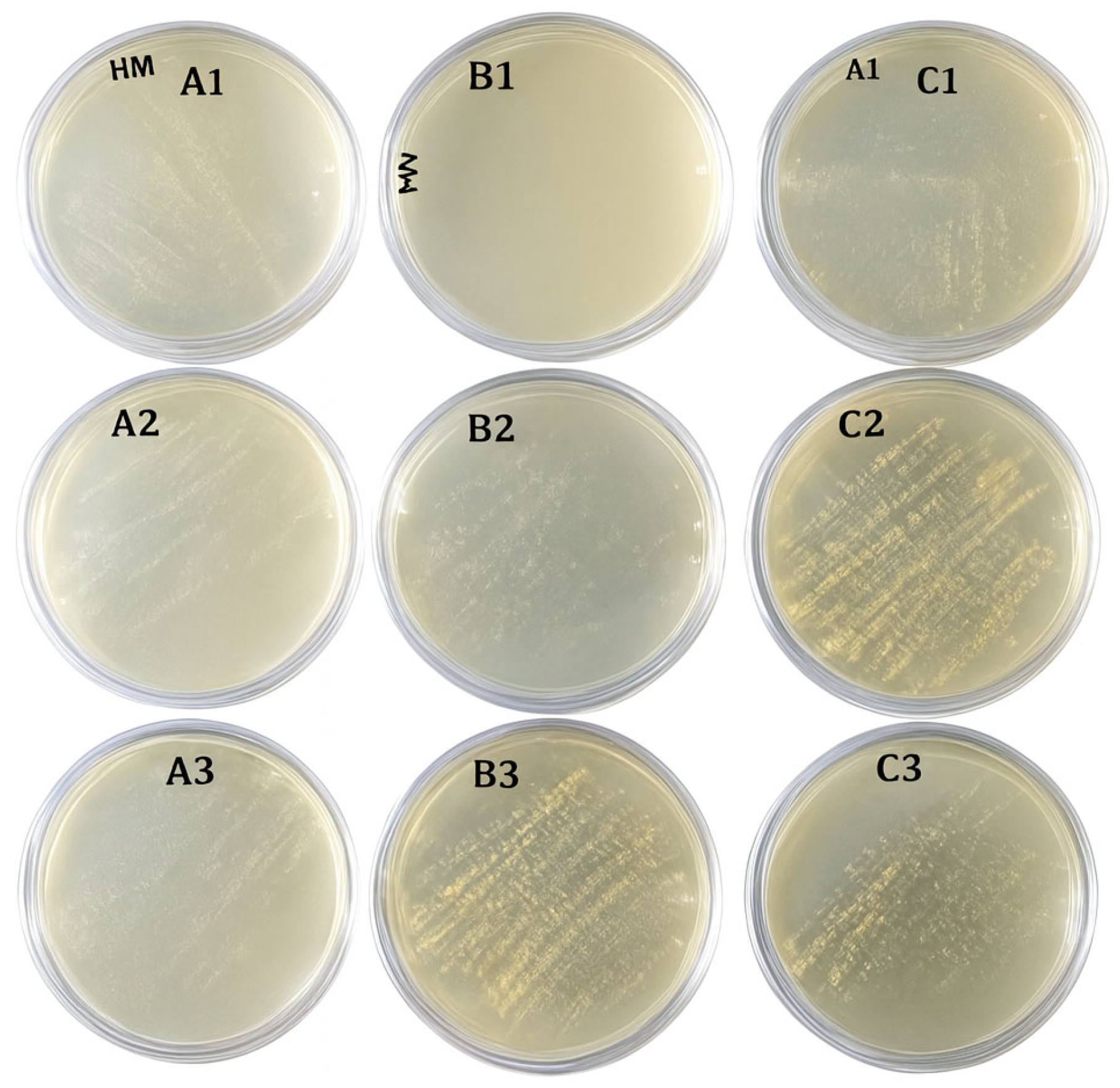

| Surface | Condition | Mean CFU/cm2 ± SD | Log10 Reduction | Significance vs. Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood | Baseline | 220.0 ± 10.0 | — | — |

| Wood | 5 min UVC | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 2.5 | <0.001 |

| Wood | 10 min UVC | 0.0 ± 0.0 | ≥2.74 | <0.001 |

| Metal | Baseline | 216.7 ± 7.6 | — | — |

| Metal | 5 min UVC | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 2.34 | <0.001 |

| Metal | 10 min UVC | 0.0 ± 0.0 | ≥2.73 | <0.001 |

| Dental | Baseline | 213.3 ± 7.6 | — | — |

| Dental | 5 min UVC | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 2.33 | <0.001 |

| Dental | 10 min UVC | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 2.85 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsolak, S.; Bud, E.; Bucur, S.M.; Păcurar, M.; Man, A.; Manuc, D. Efficacy of UVC Radiation in Reducing Bacterial Load on Dental Office Surfaces. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 596. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120596

Tsolak S, Bud E, Bucur SM, Păcurar M, Man A, Manuc D. Efficacy of UVC Radiation in Reducing Bacterial Load on Dental Office Surfaces. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):596. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120596

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsolak, Souat, Eugen Bud, Sorana Maria Bucur, Mariana Păcurar, Adrian Man, and Daniela Manuc. 2025. "Efficacy of UVC Radiation in Reducing Bacterial Load on Dental Office Surfaces" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 596. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120596

APA StyleTsolak, S., Bud, E., Bucur, S. M., Păcurar, M., Man, A., & Manuc, D. (2025). Efficacy of UVC Radiation in Reducing Bacterial Load on Dental Office Surfaces. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 596. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120596