Periodontitis and Oral Pathogens in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

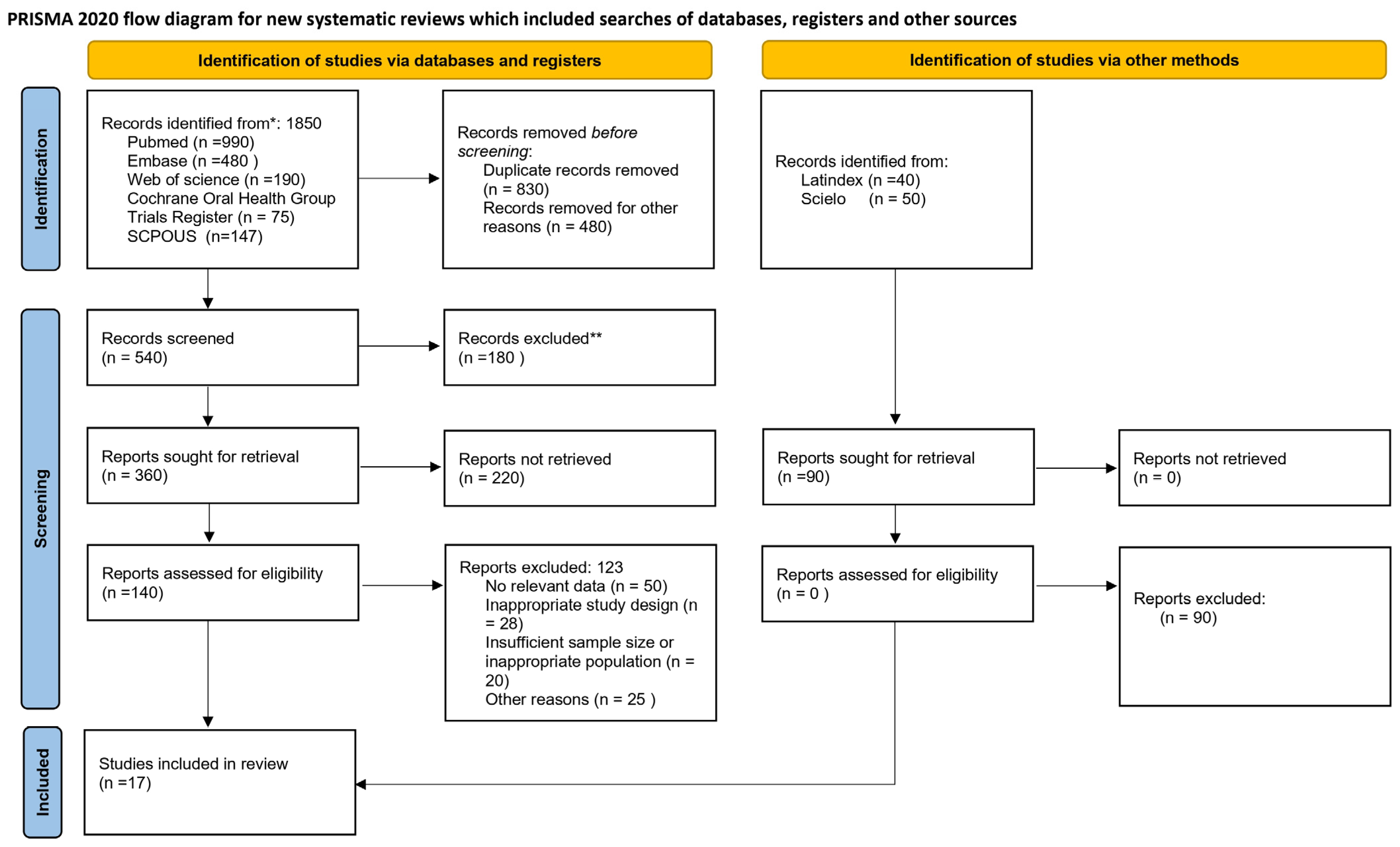

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. PICO Question

2.3. Database Search Strategy and Screening

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

- -

- Observational studies (cohorts, case–control, population-based) reporting an association between periodontitis and colorectal cancer.

- -

- Human molecular studies identifying periodontopathogenic bacteria (F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, among others) in tumor tissue, the fecal microbiome, or biological fluids of patients with colorectal cancer.

- -

- Adults (≥18 years).

- -

- Languages: English.

- -

- Published from 2000 onward.

- -

- Animal or in vitro studies.

- -

- Systematic reviews, narrative reviews, editorials, letters, comments.

- -

- Studies not reporting quantifiable risk data (OR, RR, HR, incidence) or confirmed bacterial presence.

- -

- Studies that do not clearly distinguish periodontitis from healthy controls, or an oral microbiome from the general intestinal microbiome.

2.5. Study Selection Process and Data Extraction

- Table 1 presents studies evaluating the overall relationship between periodontitis or exposure to oral pathogens and colorectal cancer risk, including prospective cohorts and case–control studies.

- Table 2 includes articles focused on Fusobacterium nucleatum, highlighting its tumor frequency, molecular associations (such as MSI or BRAF mutations), and potential prognostic value.

- Table 3 summarizes studies analyzing the involvement of Porphyromonas gingivalis in colorectal carcinogenesis and its impact on survival, in both clinical and experimental settings.

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

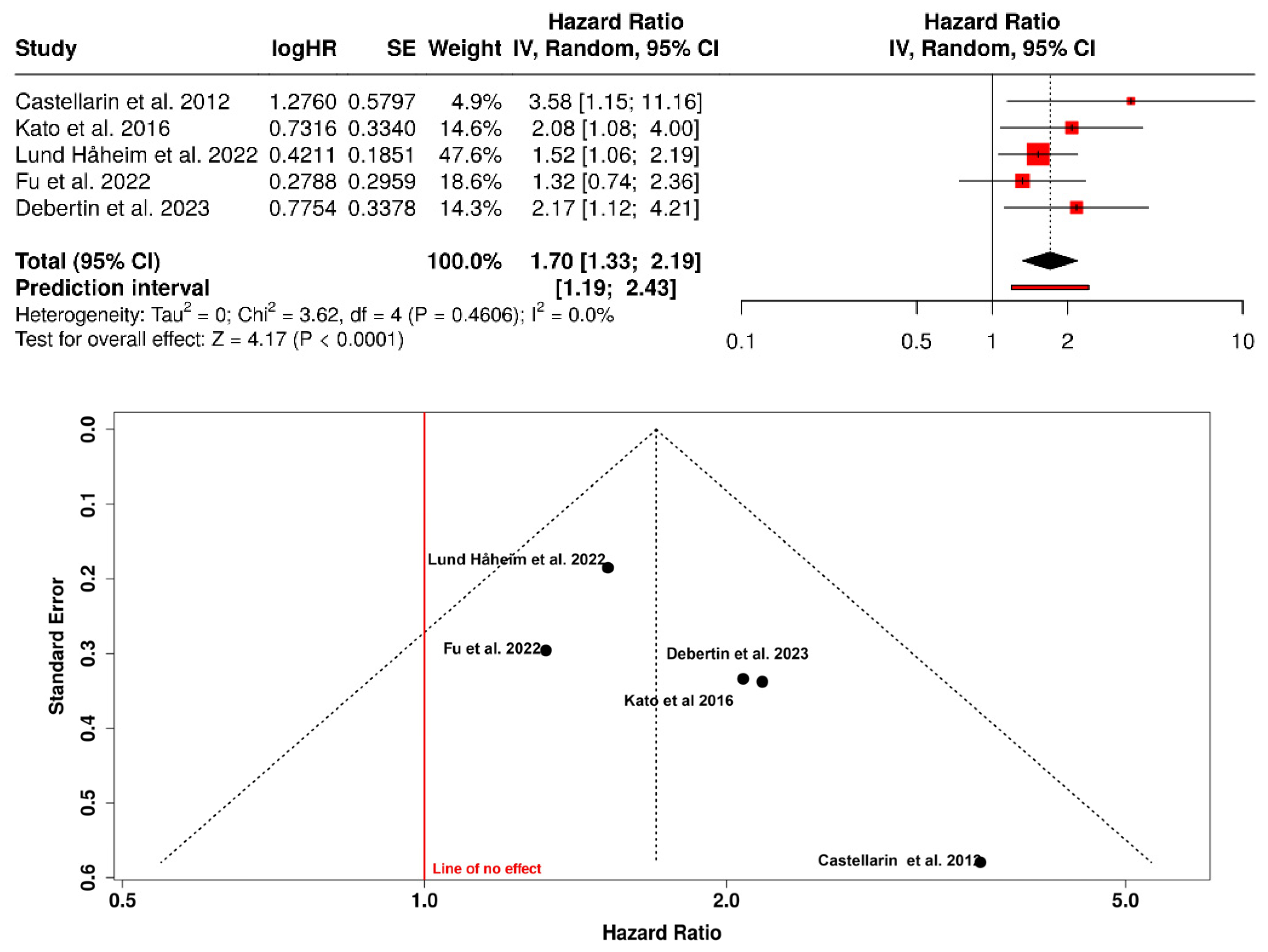

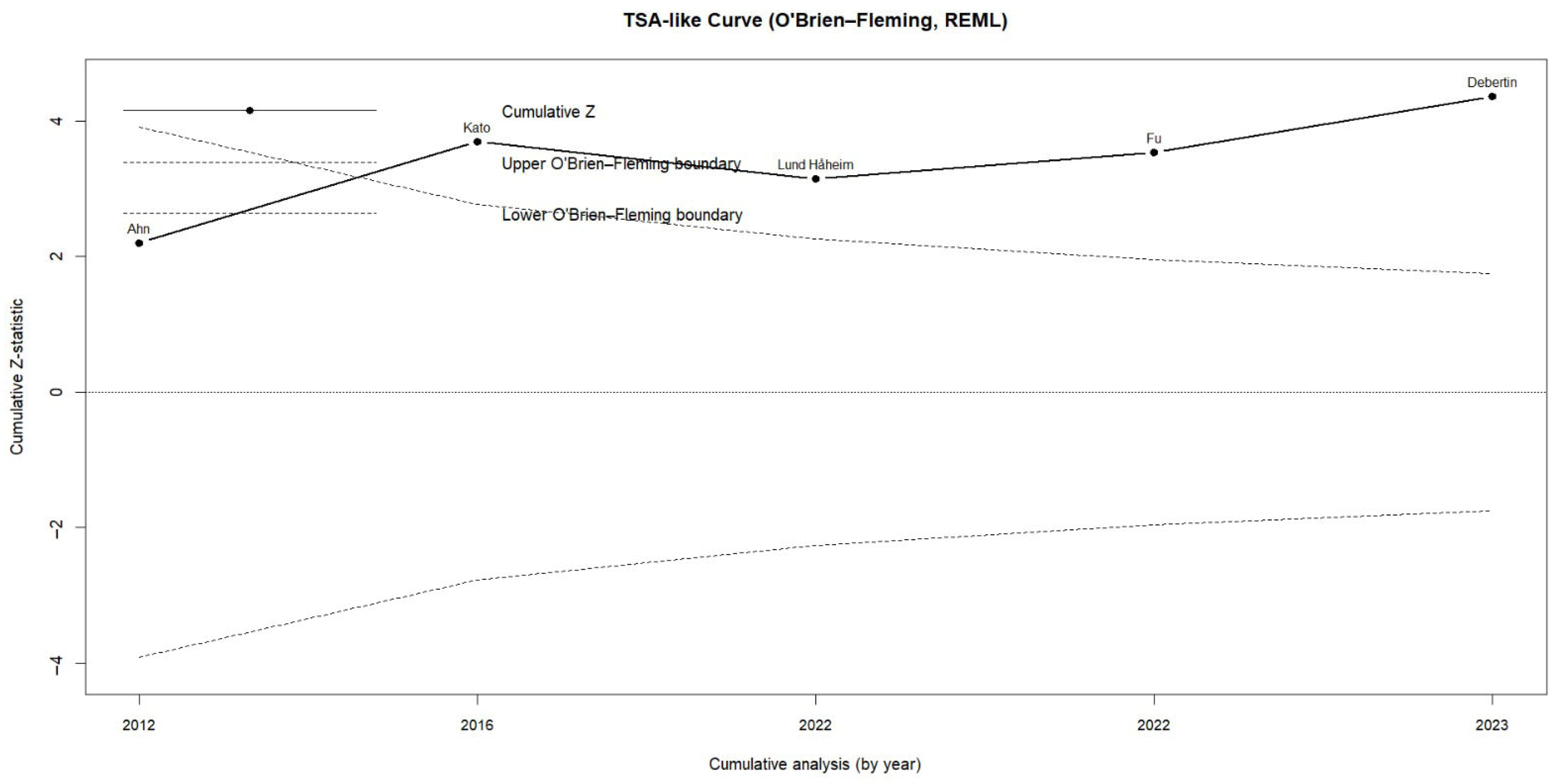

3.1. Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Patients with Periodontitis or Exposure to Oral Pathogens

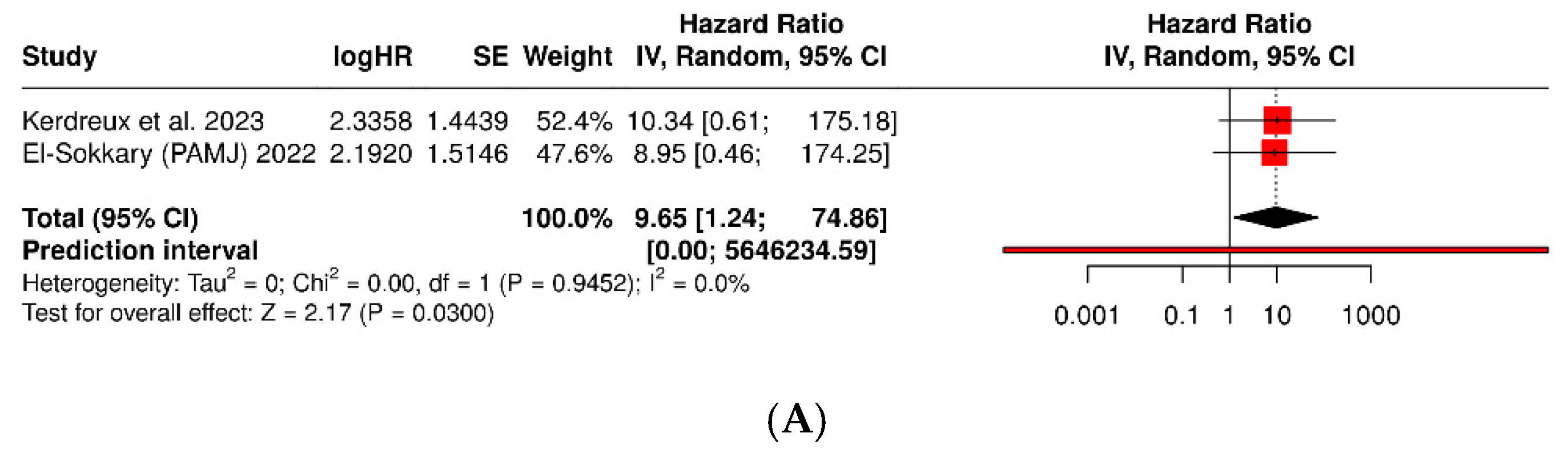

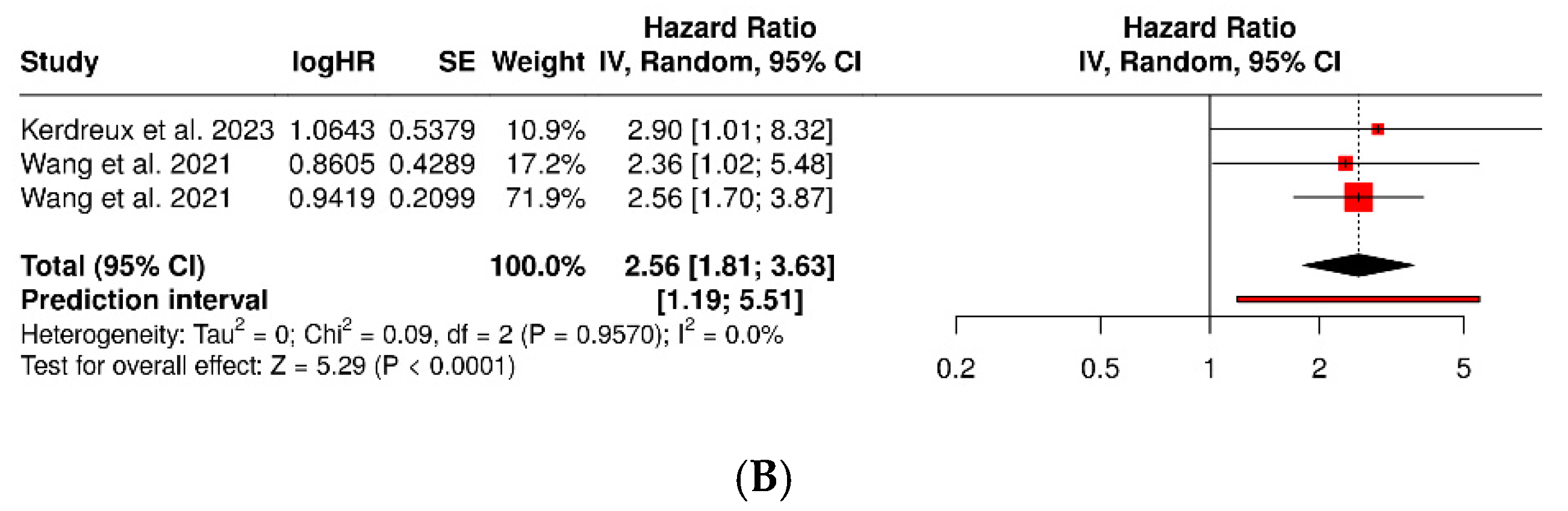

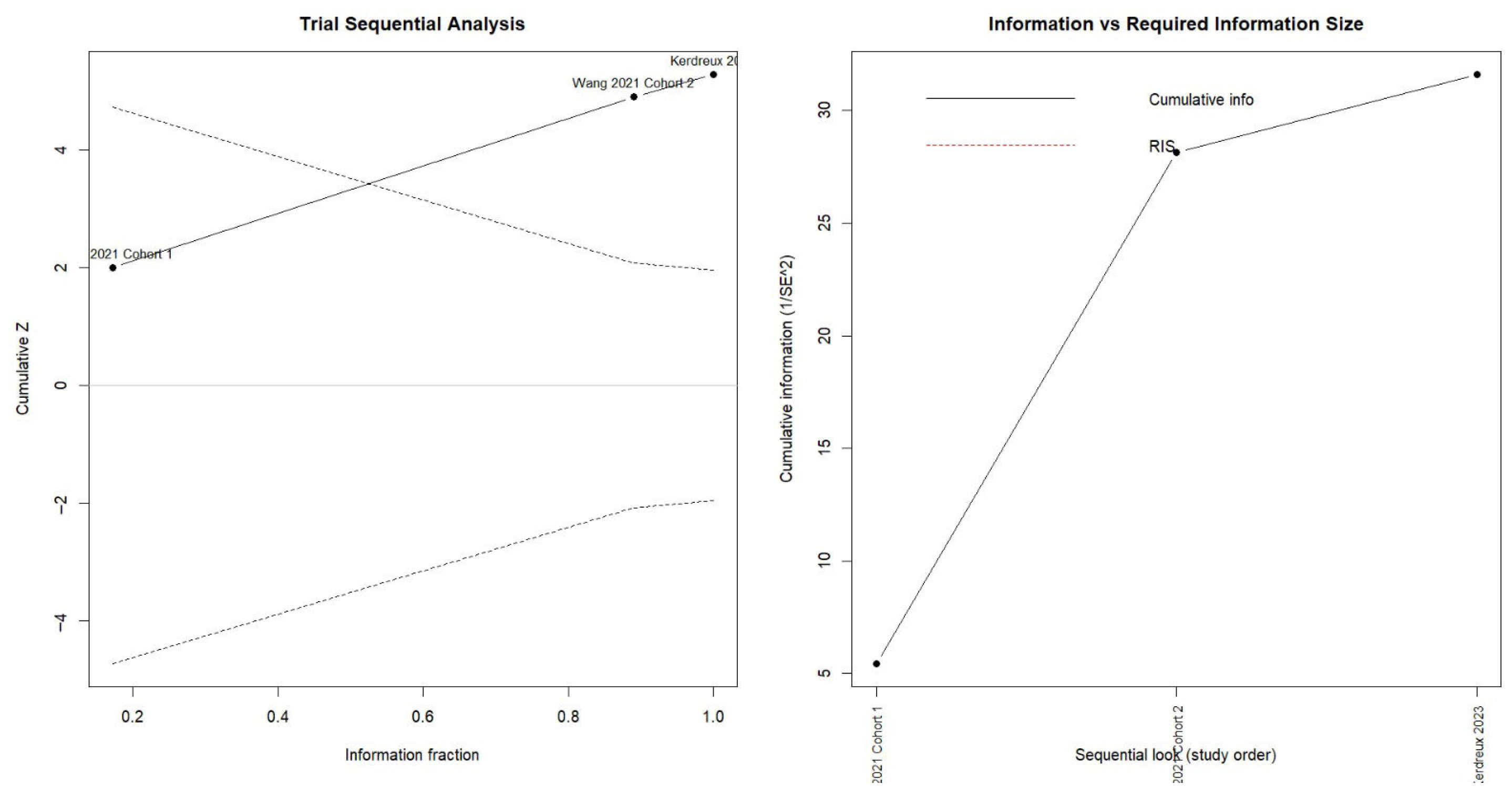

3.2. Porphyromonas Gingivalis and Colorectal Cancer

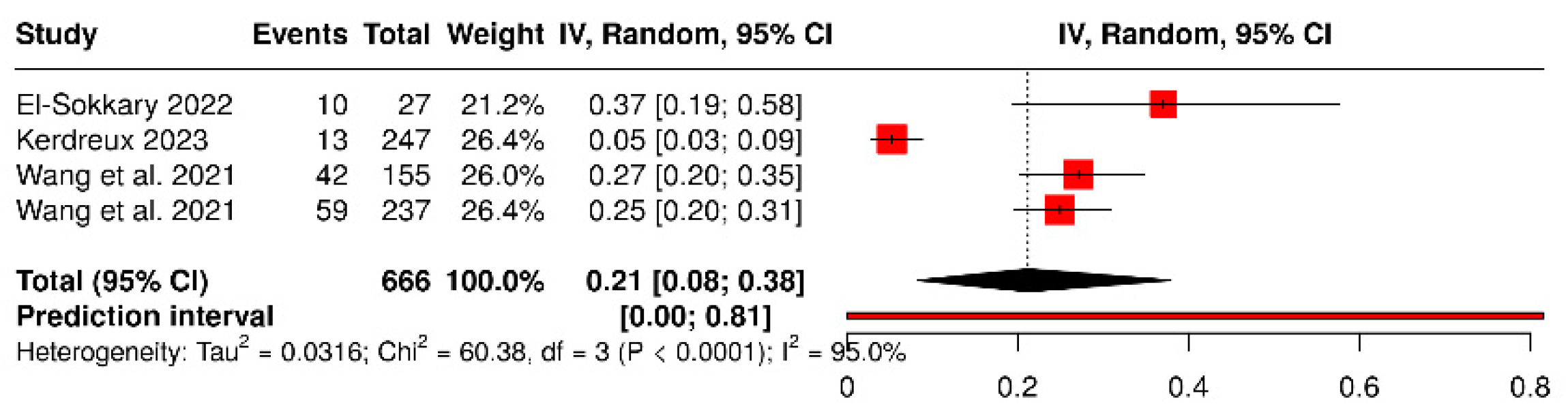

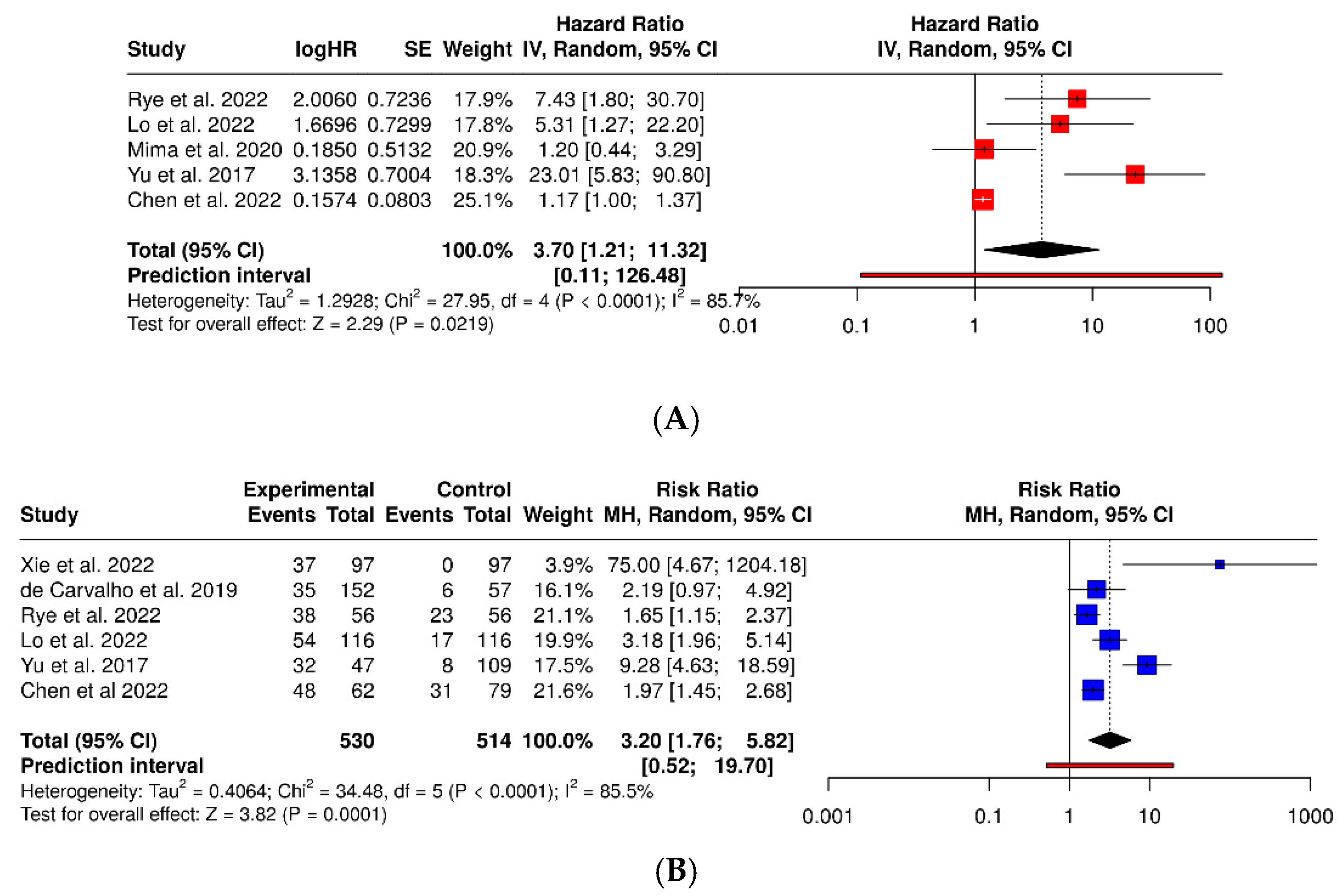

3.3. Fusobacterium Nucleatum and Colorectal Cancer

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Clinical and Research Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzahrani, S.M.; Al Doghaither, H.A.; Al-Ghafari, A.B. General insight into cancer: An overview of colorectal cancer (Review). Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 15, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Soerjomataram, I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 2021, 127, 3029–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, Y.; Xu, P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gausman, V.; Dornblaser, D.; Anand, S.; Hayes, R.B.; O’Connell, K.; Du, M.; Liang, P.S. Risk Factors Associated with Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2752–2759.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladabaum, U.; Dominitz, J.A.; Kahi, C.; Schoen, R.E. Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Gao, Z.; Huang, L.; Qin, H. Gut microbiota and colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Fang, L.; Lee, M.-H. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in promoting the development of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2018, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.; Tang, D.W.T.; Wong, S.H.; Lal, D. Gut Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer: Biological Role and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers 2023, 15, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcoholado, L.; Ramos-Molina, B.; Otero, A.; Laborda-Illanes, A.; Ordóñez, R.; Medina, J.A.; Gómez-Millán, J.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I. The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Colorectal Cancer Development and Therapy Response. Cancers 2020, 12, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipe, G.; Idiz, U.O.; Firat, D.; Bektasoglu, H. Relationship between intestinal microbiota and colorectal cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2015, 7, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemer, B.; Warren, R.D.; Barrett, M.P.; Cisek, K.; Das, A.; Jeffery, I.B.; Hurley, E.; O’Riordain, M.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. The oral microbiota in colorectal cancer is distinctive and predictive. Gut 2018, 67, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, S.C.; Agurto, M.G.; Martello, L.A. The oral-gut-circulatory axis: From homeostasis to colon cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1289452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baima, G.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Romano, F.; Aimetti, M.; Romandini, M. The Gum–Gut Axis: Periodontitis and the Risk of Gastrointestinal Cancers. Cancers 2023, 15, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholizadeh, P.; Eslami, H.; Yousefi, M.; Asgharzadeh, M.; Aghazadeh, M.; Kafil, H.S. Role of oral microbiome on oral cancers, a review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellarin, M.; Warren, R.L.; Freeman, J.D.; Dreolini, L.; Krzywinski, M.; Strauss, J.; Barnes, R.; Watson, P.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Moore, R.A.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D.; Chun, E.; Robertson, L.; Glickman, J.N.; Gallini, C.A.; Michaud, M.; Clancy, T.E.; Chung, D.C.; Lochhead, P.; Hold, G.L.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Weng, W.; Guo, B.; Cai, G.; Ma, Y.; Cai, S. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil by upregulation of BIRC3 expression in colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J.; Kim, J.H.; Bae, J.M.; Kim, H.J.; Cho, N.-Y.; Kang, G.H. Prognostic Impact of Fusobacterium nucleatum Depends on Combined Tumor Location and Microsatellite Instability Status in Stage II/III Colorectal Cancers Treated with Adjuvant Chemotherapy. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2019, 53, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdreux, M.; Edin, S.; Löwenmark, T.; Bronnec, V.; Löfgren-Burström, A.; Zingmark, C.; Ljuslinder, I.; Palmqvist, R.; Ling, A. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Colorectal Cancer and its Association to Patient Prognosis. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 1479–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; Wen, L.; Mu, W.; Wu, X.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Fang, J.; Luan, Y.; Chen, P.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes Colorectal Carcinoma by Activating the Hematopoietic NLRP3 Inflammasome. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 2745–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Jia, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, B. Intracellular Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes the Proliferation of Colorectal Cancer Cells via the MAPK/ERK Signaling Pathway. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 584798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Basabe, A.; Lattanzi, G.; Perillo, F.; Amoroso, C.; Baeri, A.; Farini, A.; Torrente, Y.; Penna, G.; Rescigno, M.; Ghidini, M.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis fuels colorectal cancer through CHI3L1-mediated iNKT cell-driven immune evasion. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2388801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motosugi, S.; Takahashi, N.; Mineo, S.; Sato, K.; Tsuzuno, T.; Aoki-Nonaka, Y.; Nakajima, N.; Takahashi, K.; Sato, H.; Miyazawa, H.; et al. Enrichment of Porphyromonas gingivalis in colonic mucosa-associated microbiota and its enhanced adhesion to epithelium in colorectal carcinogenesis: Insights from in vivo and clinical studies. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, D.S.; Fu, Z.; Shi, J.; Chung, M. Periodontal Disease, Tooth Loss, and Cancer Risk. Epidemiol. Rev. 2017, 39, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momen-Heravi, F.; Babic, A.; Tworoger, S.S.; Zhang, L.; Wu, K.; Smith-Warner, S.A.; Ogino, S.; Chan, A.T.; Meyerhardt, J.; Giovannucci, E.; et al. Periodontal disease, tooth loss and colorectal cancer risk: Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, I.; Vasquez, A.A.; Moyerbrailean, G.; Land, S.; Sun, J.; Lin, H.-S.; Ram, J.L. Oral microbiome and history of smoking and colorectal cancer. J. Epidemiol. Res. 2016, 2, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Håheim, L.L.; Thelle, D.S.; Rønningen, K.S.; Olsen, I.; Schwarze, P.E. Low level of antibodies to the oral bacterium Tannerella forsythia predicts bladder cancers and Treponema denticola predicts colon and bladder cancers: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272148. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.M.; Chien, W.; Chung, C.; Lee, W.; Tu, H.; Fu, E. Is periodontitis a risk factor of benign or malignant colorectal tumor? A population-based cohort study. J. Periodontal Res. 2022, 57, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debertin, J.; Teles, F.; Martin, L.M.; Lu, J.; Koestler, D.C.; Kelsey, K.T.; Beck, J.D.; Platz, E.A.; Michaud, D.S. Antibodies to oral pathobionts and colon cancer risk in the CLUE I cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 153, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

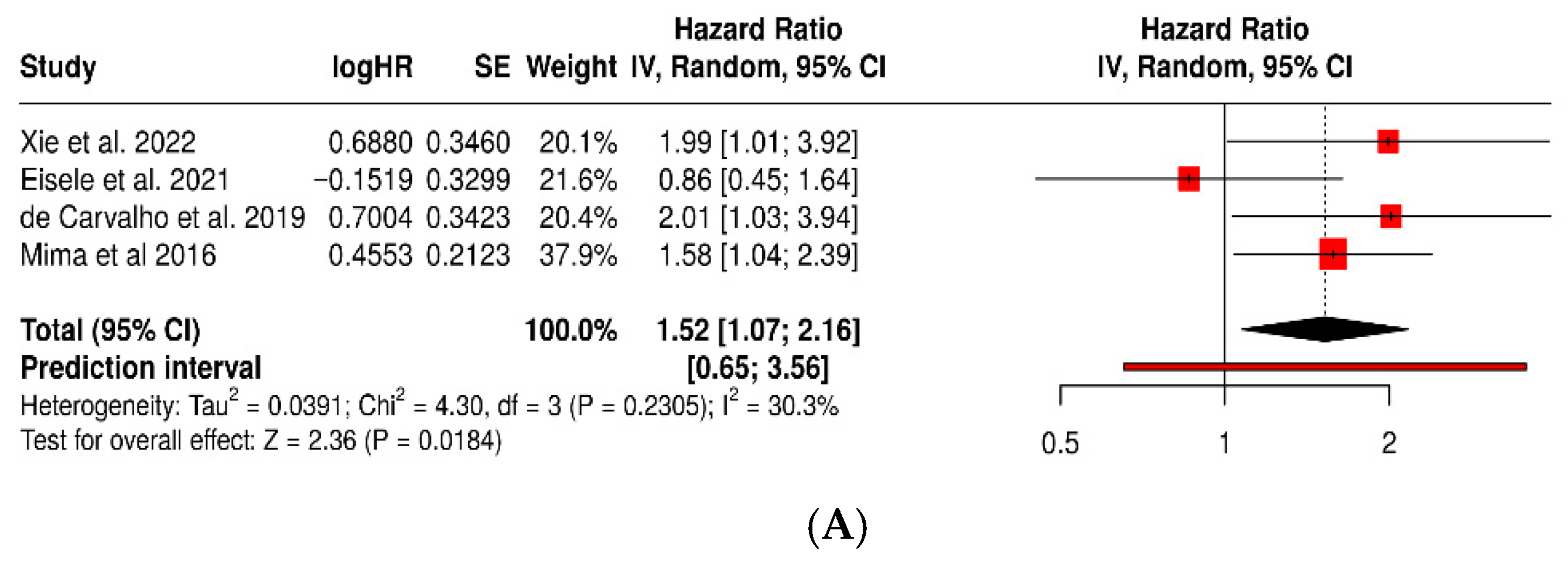

- Xie, Y.; Jiao, X.; Zeng, M.; Fan, Z.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xia, Y. Clinical Significance of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Microsatellite Instability in Evaluating Colorectal Cancer Prognosis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2022, 14, 3021–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisele, Y.; Mallea, P.M.; Gigic, B.; Stephens, W.Z.; Warby, C.A.; Buhrke, K.; Lin, T.; Boehm, J.; Schrotz-King, P.; Hardikar, S.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Clinicopathologic Features of Colorectal Cancer: Results from the ColoCare Study. Clin. Color. Cancer 2021, 20, e165–e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carvalho, A.C.; De Mattos Pereira, L.; Datorre, J.G.; dos Santos, W.; Berardinelli, G.N.; de Medeiros Matsushita, M.; Oliveira, M.A.; Durães, R.O.; Guimarães, D.P.; Reis, R.M. Microbiota Profile and Impact of Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer Patients of Barretos Cancer Hospital. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mima, K.; Nishihara, R.; Qian, Z.R.; Cao, Y.; Sukawa, Y.; Nowak, J.A.; Yang, J.; Dou, R.; Masugi, Y.; Song, M.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis. Gut 2016, 65, 1973–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

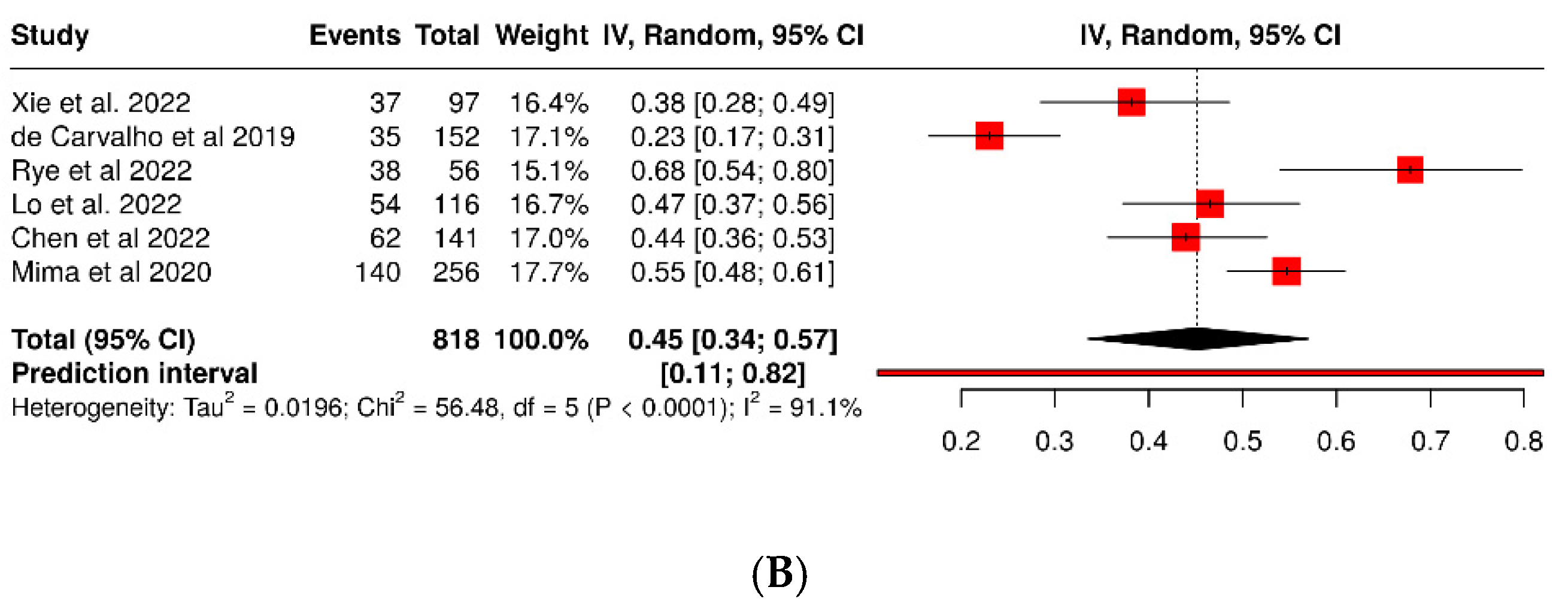

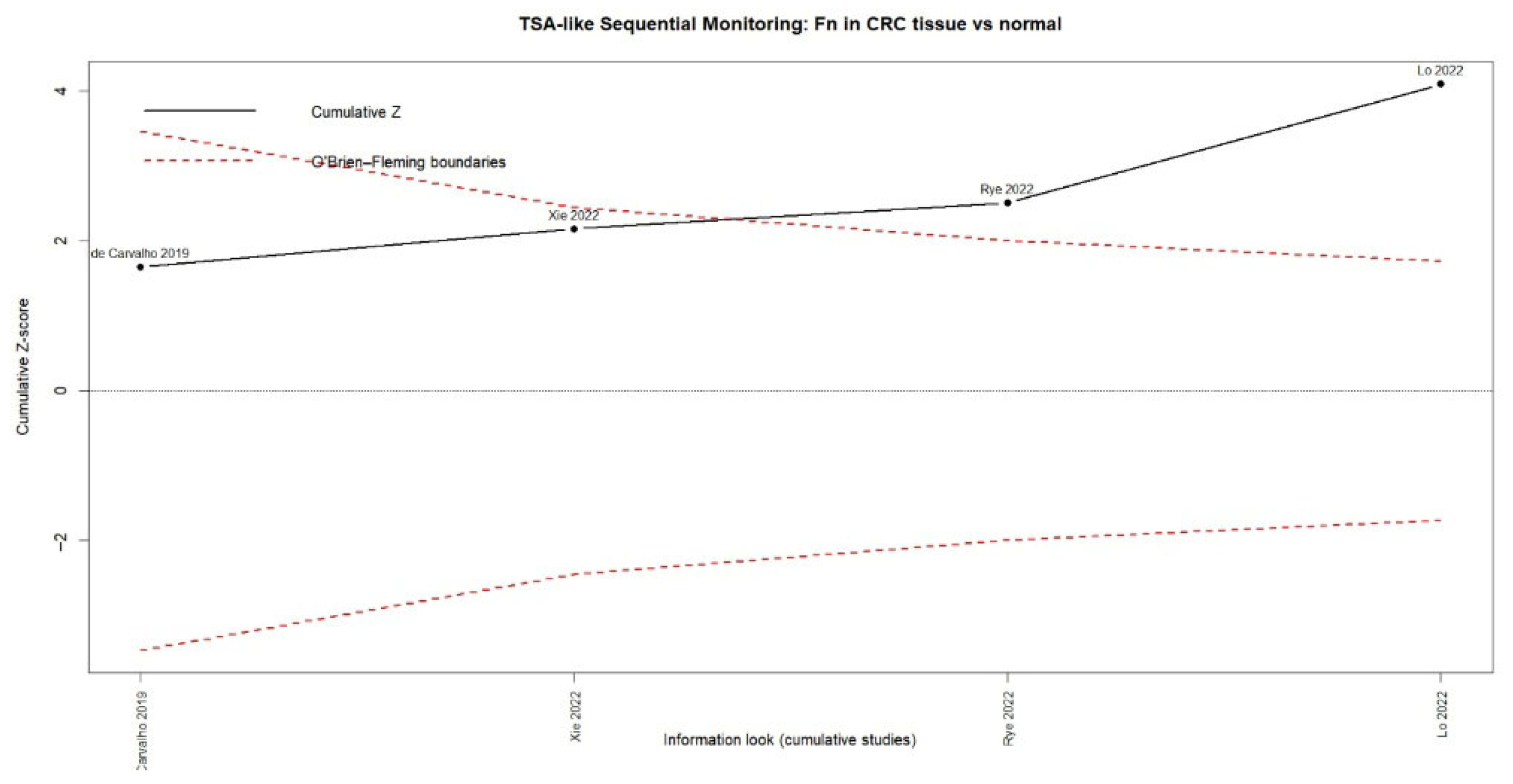

- Rye, M.S.; Garrett, K.L.; Holt, R.A.; Platell, C.F.; McCoy, M.J. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Bacteroides fragilis detection in colorectal tumours: Optimal target site and correlation with total bacterial load. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, C.-H.; Wu, D.-C.; Jao, S.-W.; Wu, C.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chuang, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-B.; Chen, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-T.; Chen, J.-H.; et al. Enrichment of Prevotella intermedia in human colorectal cancer and its additive effects with Fusobacterium nucleatum on the malignant transformation of colorectal adenomas. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mima, K.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kosumi, K.; Ogata, Y.; Miyake, K.; Hiyoshi, Y.; Ishimoto, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; Baba, Y.; Iwagami, S.; et al. Mucosal cancer-associated microbes and anastomotic leakage after resection of colorectal carcinoma. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 32, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Feng, Q.; Wong, S.H.; Zhang, D.; Liang, Q.Y.; Qin, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhao, H.; Stenvang, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut 2017, 66, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Yue, C.-B.; Wang, Y.-L.; Pan, H.-W.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum Is a Risk Factor for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Curr. Med. Sci. 2022, 42, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sokkary, M.M.A. Molecular characterization of gut microbial structure and diversity associated with colorectal cancer patients in Egypt. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 43, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gethings-Behncke, C.; Coleman, H.G.; Jordao, H.W.; Longley, D.B.; Crawford, N.; Murray, L.J.; Kunzmann, A.T. Fusobacterium nucleatum in the Colorectum and Its Association with Cancer Risk and Survival: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wei, W.; Zheng, D. Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer: Ally Mechanism and Targeted Therapy Strategies. Research 2025, 8, 0640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadgar-Zankbar, L.; Elahi, Z.; Shariati, A.; Khaledi, A.; Razavi, S.; Khoshbayan, A. Exploring the role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer: Implications for tumor proliferation and chemoresistance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, C.G.; Kim, W.K.; Kim, K.-A.; Yoo, J.; Min, B.S.; Paik, S.; Shin, S.J.; Lee, H.; Lee, K.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces a tumor microenvironment with diminished adaptive immunity against colorectal cancers. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1101291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelbary, M.M.H.; Abdallah, R.Z.; Na, H.S. Editorial: The oral-gut axis: From ectopic colonization to within-host evolution of oral bacteria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1378237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, H.; Zhen, Y.; Wu, B.; Li, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhou, H. Oral Fusobacterium nucleatum resists the acidic pH of the stomach due to membrane erucic acid synthesized via enoyl-CoA hydratase-related protein FnFabM. J. Oral Microbiol. 2025, 17, 2453964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herath, T.D.K.; Darveau, R.P.; Seneviratne, C.J.; Wang, C.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Jin, L. Tetra- and penta-acylated lipid A structures of Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS differentially activate TLR4-mediated NF-κB signal transduction cascade and immuno-inflammatory response in human gingival fibroblasts. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeger, S.; Jarzina, F.; Domann, E.; Meyle, J. Porphyromonas gingivalis activates NFκB and MAPK pathways in human oral epithelial cells. BMC Immunol. 2017, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, L.; Soto, C.; Tapia, H.; Pacheco, M.; Tapia, J.; Osses, G.; Salinas, D.; Rojas-Celis, V.; Hoare, A.; Quest, A.F.G.; et al. Co-Culture of P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum Synergistically Elevates IL-6 Expression via TLR4 Signaling in Oral Keratinocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, F.; An, L.; Yuan, H.; Wen, F.; Xu, Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis induced UCHL3 to promote colon cancer progression. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2023, 13, 5981–5995. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.H.; Kwong, T.N.Y.; Chow, T.-C.; Luk, A.K.C.; Dai, R.Z.W.; Nakatsu, G.; Lam, T.Y.T.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; et al. Quantitation of faecal Fusobacterium improves faecal immunochemical test in detecting advanced colorectal neoplasia. Gut 2017, 66, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Deng, J.; Donati, V.; Merali, N.; Frampton, A.E.; Giovannetti, E.; Deng, D. The Roles and Interactions of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum in Oral and Gastrointestinal Carcinogenesis: A Narrative Review. Pathogens 2024, 13, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (Year) | Country/Cohort | Study Design | N (Total) | CRC Cases | Controls | Exposure/Detection Method | Tumor Type/Sample | HR (95% CI) | Main Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castellarin et al., 2012 [17] | Canada—BC Cancer Agency Tumor Repository | Case–control (tumor tissue vs. healthy tissue) | 198 | 99 | 99 | Detection of Fusobacterium nucleatum DNA by qPCR and RNA-seq | Colorectal tissue | 3.58 [1.15–11.16] | F. nucleatum was ~415× more abundant in tumor tissue and was associated with lymph node metastasis. |

| Kato et al., 2016 [29] | USA—Detroit Metropolitan Area | Population-based case–control | 190 | 68 | 122 | 16S rRNA sequencing of the oral microbiome (mouth rinse) | Self-reported CRC history | 2.08 [1.08–4.00] | Higher abundance of Lactobacillus and Rothia in participants with a history of CRC; potential role of oral dysbiosis. |

| Lund Håheim et al., 2022 [30] | Norway—Oslo Cohort | Prospective cohort (17.5-year follow-up) | 621 | 26 | 595 | Serum IgG antibodies against T. denticola, T. forsythia, P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans (ELISA) | Colon cancer (ICD-10: C18) | 1.52 [1.06–2.19] | Low antibody titers to T. denticola were associated with higher risk of colon cancer. |

| Fu et al., 2022 [31] | Taiwan—NHIRD | Population-based retrospective cohort (15 years) | 35,124 | 3865 | 31,259 | Clinical diagnosis of periodontitis (ICD-9-CM) | Benign and malignant colorectal tumors | 1.32 [0.74–2.36] | Periodontitis was associated with higher risk of benign colorectal tumors; positive, non-significant trend for malignant tumors. |

| Debertin et al., 2023 [32] | USA—CLUE I Cohort (Maryland) | Nested prospective cohort (matched case–control) | 400 | 200 | 200 | Serum IgG antibodies against oral pathogens (A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, etc.) | Colon cancer | 2.17 [1.12–4.21] | High immune response to A. actinomycetemcomitans doubled the risk of colon cancer. |

| Author (Year) | Country (Cohort) | Study Design | N (Total) | CRC Cases | Controls | Exposure Method | Tumor Type | CRC Diagnostic Method | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xie et al. (2022) [33] | China | Retrospective observational (tumor tissue vs. adjacent) | 368 | 184 CRC | 184 adjacent (internal) | Immunohistochemistry (Fn and MSI) | Colon and rectum | Histopathology | Fn positivity predicts worse survival. |

| Eisele et al. (2021) [34] | Germany, USA | Prospective cohort (ColoCare) | 105 | 105 CRC | 0 (no external controls) | qPCR in stool (Fn DNA) | Colon vs. rectum | Histopathology | High fecal Fn associated with rectal tumor, not survival. |

| de Carvalho et al. (2019) [35] | Brazil | Retrospective cohort (tumor tissue vs. adjacent) | 209 | 152 CRC | 57 adjacent (internal) | qPCR in tumor tissue | Colon and rectum | Histopathology | Fn associated with MSI+, BRAF mutation, and worse survival. |

| Mima et al. (2016) [36] | USA (NHS + HPFS) | Prospective cohort | 1069 | 1069 CRC | 0 (no external controls) | qPCR in tumor tissue | Colon and rectum | Centralized histopathology | High Fn load associated with CRC-specific mortality. |

| Rye et al. (2022) [37] | Norway (ColoCare) | Prospective cohort (tumor/adjacent pairs) | 112 | 56 CRC | 56 adjacent (internal) | qPCR in tumor and adjacent tissue | Colon and rectum | Histopathology | Fn more frequent in tumor; association with proximal location. |

| Lo et al. (2022) [38] | Taiwan | Retrospective + molecular cohort | 203 | 116 CRC | 87 (35 adenomas + 52 normal mucosa) | 16S rRNA + qPCR (Prevotella, Fn) | Colon and rectum | Histopathology | P. intermedia and Fn promote invasion and metastasis. |

| Mima et al. (2020) [39] | Japan (Kumamoto Univ.) | Retrospective surgical cohort (operated CRC) | 256 | 256 CRC | 0 (no external controls) | qPCR in fresh tumor tissue | Colon and rectum | Histopathology | High Bifidobacterium levels ↑ risk of anastomotic leakage; Fn not significant. |

| Yu et al. (2017) [40] | China, Denmark, France, Austria | Multicenter case–control + validation (fecal) | Discovery: 128 (74 CRC, 54 ctrls); Validation: 156 (47 CRC, 109 ctrls) | 121 CRC (disc. + val.) | 163 external controls (54 + 109) | Metagenomic sequencing + qPCR (Fn, Parvimonas, Peptostreptococcus) | Colon and rectum | Colonoscopy + histopathology | Fecal Fn and Parvimonas micra are robust biomarkers for CRC. |

| Chen et al. (2022) [41] | China (Qilu Hospital, Shandong Univ.) | Retrospective cohort + meta-analysis | 141 | 141 CRC (63 LN+, 16 M1) | 0 (within-CRC comparison) | qPCR in tumor tissue (Fn DNA) | Colon and rectum | Histopathology + TNM | High intratumoral Fn predicts nodal and distant metastasis. |

| Author (Year) | Country/Cohort | Study Design | N (Total) | CRC Cases | Controls | Exposure/Detection Method for P. gingivalis | Tumor Type/Model | CRC Diagnostic Method | Main Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kerdreux et al., 2023 [21] | Sweden—U-CAN and FECSU cohorts | Cross-sectional (CRC, dysplasia, and controls) | 563 | 285 (CRC: 247 U-CAN + 38 FECSU) | 150 (89 U-CAN + 61 FECSU) | qPCR in stool and tumor tissue for P. gingivalis | Colorectal adenocarcinoma (MSI/MSS; mucinous/non-mucinous) | Clinical and histopathological within institutional cohorts | P. gingivalis detected in 2.6–5.3% of cases; associated with MSI tumors and lower cancer-specific survival (p = 0.04). |

| El-Sokkary, 2022 [42] | Egypt—Mansoura Oncology Hospital | Case–control (stool PCR) | 34 | 27 | 7 | Conventional PCR and qPCR for 11 bacterial species, incl. P. gingivalis | Clinically diagnosed CRC | Hospital clinical diagnosis + histopathological confirmation | P. gingivalis detected only in cases (0% in controls); co-occurs with Fusobacterium and Prevotella. Potential fecal biomarker. |

| Wang et al., 2021 [22] | China—Sun Yat-sen University Hospital | Translational: case–control (CRC vs. adenoma vs. healthy) + prognostic cohort (two CRC cohorts) | >400 humans (392 in CRC cohorts + case–control group) | 392 | NR (adenoma + healthy) | qPCR and immunohistochemistry in tissue and stool; oral infection in murine models | Human CRC; orthotopic models and Apc^Min/+^ | Histology + TNM staging | P. gingivalis enriched in CRC vs. adenoma/healthy; high tumor burden → worse OS/RFS (HR ≈ 2.3–2.6). Promotes CRC via hematopoietic NLRP3 inflammasome. |

| Study | Confounding | Exposure Classification | Outcome Measurement | Overall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castellarin 2012 [17] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| Kato 2016 [29] | Some concerns | Some concerns | High (self-reported CRC) | Some/High |

| Lund Håheim 2022 [30] | Some concerns (serology as proxy) | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns |

| Fu 2022 [31] | High (limited adjustment) | Some concerns (ICD) | Some concerns | High |

| Debertin 2023 [32] | Some concerns | Some concerns (IgG panel) | Low | Some concerns |

| Study | Selection | Index Test (qPCR/16S/IHC) | Confounders/Analysis (If Prognostic) | Overall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xie 2022 [33] | Some concerns | Some concerns (IHC variability) | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Eisele 2021 [34] | Some concerns (cases only) | Some concerns (fecal thresholds) | Low | Some concerns |

| de Carvalho 2019 [35] | Some concerns | Low (tissue qPCR) | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Mima 2016 [36] | Low | Low (tissue qPCR) | Low (adjusted Cox) | Low |

| Rye 2022 [37] | Low (tumor/adjacent pairs) | Low (qPCR) | Low | Low |

| Study | Selection | Pg Detection (qPCR/PCR/IHC) | Confounders/Analysis (If Prognostic) | Overall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kerdreux 2023 [21] | Low | Some concerns (low prevalence, LOD) | Some concerns (CSS, MSI) | Some concerns |

| El-Sokkary 2022 [42] | High (small sample, hospital controls) | Some/High | Low | High |

| Wang 2021 [22] | Some concerns | Low (concordant qPCR/IHC) | Low (Cox adjusted for TNM) | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chauca-Bajaña, L.; Ordoñez Balladares, A.; Lorenzo-Pouso, A.I.; Caicedo-Quiroz, R.; Erazo Vaca, R.X.; Dau Villafuerte, R.F.; Avila-Granizo, Y.V.; Salazar Minda, C.H.; Salavarria Vélez, M.A.; Velásquez Ron, B. Periodontitis and Oral Pathogens in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120595

Chauca-Bajaña L, Ordoñez Balladares A, Lorenzo-Pouso AI, Caicedo-Quiroz R, Erazo Vaca RX, Dau Villafuerte RF, Avila-Granizo YV, Salazar Minda CH, Salavarria Vélez MA, Velásquez Ron B. Periodontitis and Oral Pathogens in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(12):595. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120595

Chicago/Turabian StyleChauca-Bajaña, Luis, Andrea Ordoñez Balladares, Alejandro Ismael Lorenzo-Pouso, Rosangela Caicedo-Quiroz, Rafael Xavier Erazo Vaca, Rolando Fabricio Dau Villafuerte, Yajaira Vanessa Avila-Granizo, Carlos Hans Salazar Minda, Miguel Amador Salavarria Vélez, and Byron Velásquez Ron. 2025. "Periodontitis and Oral Pathogens in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 12: 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120595

APA StyleChauca-Bajaña, L., Ordoñez Balladares, A., Lorenzo-Pouso, A. I., Caicedo-Quiroz, R., Erazo Vaca, R. X., Dau Villafuerte, R. F., Avila-Granizo, Y. V., Salazar Minda, C. H., Salavarria Vélez, M. A., & Velásquez Ron, B. (2025). Periodontitis and Oral Pathogens in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis. Dentistry Journal, 13(12), 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13120595