Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Towards Treating Pregnant Patients Among Dental Professionals in Russia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

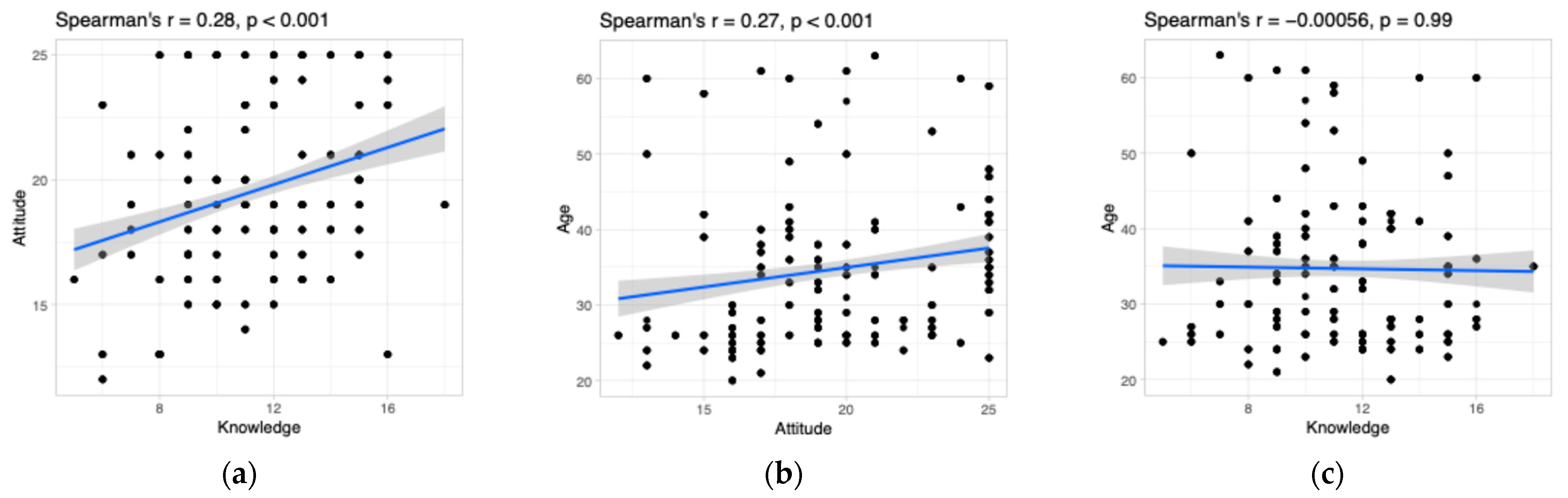

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| df | Degree of freedom |

References

- Hyder, T.; Khan, S.; Moosa, Z.H. Dental Care Of The Pregnant Patient: An Update Of Guidelines And Recommendations. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2023, 73, 2041–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mockridge, A.; Maclennan, K. Physiology of Pregnancy. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 20, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E. Exercise in Pregnancy. Aust. Fam. Physician 2014, 43, 541–542. [Google Scholar]

- AlHalal, H.; Albayyat, R.M.; Alfhaed, N.K.; Fatani, O.; Fatani, B. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Periodontal and Dental Diseases During Pregnancy Among Obstetricians and Dentists in King Saud University Medical City. Cureus 2023, 15, e47098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.S.; Yang, C.; Cohen, V.; Russell, S.L. What Factors Influence Dental Faculty’s Willingness to Treat Pregnant Women? JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2022, 7, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.S.; Arima, L.Y.; Werneck, R.I.; Moysés, S.J.; Baldani, M.H. Determinants of Dental Care Attendance during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Caries Res. 2018, 52, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Ajwani, S.; Bhole, S.; Dahlen, H.; Reath, J.; Korda, A.; Ng Chok, H.; Miranda, C.; Villarosa, A.; Johnson, M. Knowledge, Attitude and Practises of Dentists towards Oral Health Care during Pregnancy: A Cross Sectional Survey in New South Wales, Australia. Aust. Dent. J. 2017, 62, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhong, Y.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J. Physiology of Pregnancy and Oral Local Anesthesia Considerations. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, V.; Bacci, C.; Volpato, A.; Bandiera, M.; Favero, L.; Zanette, G. Pregnancy and Dentistry: A Literature Review on Risk Management during Dental Surgical Procedures. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Montalvo, E.; Córdova-Limaylla, N.; Ladera-Castañeda, M.; López-Gurreonero, C.; Echavarría-Gálvez, A.; Cornejo-Pinto, A.; Cervantes-Ganoza, L.; Cayo-Rojas, C. Factors Associated with Knowledge about Pharmacological Management of Pregnant Women in Peruvian Dental Students: A Logistic Regression Analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyapati, R.; Cherukuri, S.A.; Bodduru, R.; Kiranmaye, A. Influence of Female Sex Hormones in Different Stages of Women on Periodontium. J. Midlife Health 2022, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, A.K.; Varghese, J.; Fernandes, A.J. The Impact of Sex Hormones on the Periodontium During a Woman’s Lifetime: A Concise-Review Update. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2022, 9, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, H.C.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, K.M.; Han, S.W.; Oh, M.J. Association between Dental Caries and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velosa-Porras, J.; Rodríguez Malagón, N. Prevalence of Dental Caries in Pregnant Colombian Women and Its Associated Factors. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecci-Lloret, M.P.; Linares-Pérez, C.; Pecci-Lloret, M.R.; Rodríguez-Lozano, F.J.; Oñate-Sánchez, R.E. Oral Manifestations in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragoneses, J.; Suárez, A.; Rodríguez, C.; Algar, J.; Aragoneses, J.M. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices among Dental Practitioners Regarding Antibiotic Prescriptions for Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women in the Dominican Republic. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.S.-Y.; Milgrom, P.; Huebner, C.E.; Conrad, D.A. Dentists’ Perceptions of Barriers to Providing Dental Care to Pregnant Women. Women’s Health Issues 2010, 20, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobetsis, Y.A.; Ide, M.; Gürsoy, M.; Madianos, P.N. Periodontal Diseases and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Present and Future. Periodontol 2000 2023, 83, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Hoang, H.; Bridgman, H.; Crocombe, L.; Bettiol, S. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Consensus Statements for Antenatal Oral Healthcare: An Assessment of Their Methodological Quality and Content of Recommendations. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, T.; Bazvand, L.; Ghojazadeh, M. Diagnostic Dental Radiation Risk during Pregnancy: Awareness among General Dentists in Tabriz. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2011, 5, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregnancy|American Dental Association. Available online: https://www.ada.org/resources/ada-library/oral-health-topics/pregnancy (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Bao, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Rasubala, L.; Ren, Y.F. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Oral Health Care during Pregnancy: A Systematic Evaluation and Summary Recommendations for General Dental Practitioners. Quintessence Int. 2022, 53, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi, T.; Saberi, E.A.; Tabatabaie, A.M.; Tahmasebi, E. Antibiotic Use in Endodontic Treatment during Pregnancy: A Narrative Review. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2022, 32, 10813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Bozzo, P.; Koren, G.; Einarson, A. FDA Pregnancy Risk Categories and the CPS: Do They Help or Are They a Hindrance? Can. Fam. Physician 2010, 56, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Hagai, A.; Diav-Citrin, O.; Shechtman, S.; Ornoy, A. Pregnancy Outcome after in Utero Exposure to Local Anesthetics as Part of Dental Treatment: A Prospective Comparative Cohort Study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2015, 146, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medication Guides. Available online: https://dps.fda.gov/medguide (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Guidelines for Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy and Lactation|ACOG. Available online: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2017/10/guidelines-for-diagnostic-imaging-during-pregnancy-and-lactation (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- The Selection of Patients for Dental Radiographic Examinations|FDA. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/radiation-emitting-products/medical-x-ray-imaging/selection-patients-dental-radiographic-examinations#patient_selection_criteria (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Kamalabadi, Y.M.; Campbell, M.K.; Zitoun, N.M.; Jessani, A. Unfavourable Beliefs about Oral Health and Safety of Dental Care during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazir, S.S.; Ghosh, S.; Mahanta, S.; Shah, R.; Das, A.; Patil, S. Knowledge, Attitude and Perception toward Radiation Hazards and Protection among Dental Undergraduates, Interns and Dental Surgeons—A Questionnaire-Based Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Radiol. Pathol. Surg. 2019, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzamzami, Z.T.; Abulhamael, A.M.; Talim, D.J.; Khawaji, H.; Barzanji, S.; Roges, R.A. Cone-Beam Computed Tomographic Usage: Survey of American Endodontists. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2019, 20, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ibhawoh, L.; Enabulele, J. Endodontic Treatment of the Pregnant Patient: Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Dental Residents. Niger. Med. J. 2015, 56, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, S.A.; Jacks, M.E.; Prihoda, T.J.; McComas, M.J.; Hernandez, E.E. Oral Care for Pregnant Patients: A Survey of Dental Hygienists’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice. J. Dent. Hyg. 2016, 90, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Razban, M.; Giannopoulou, C. Knowledge and Practices of Oral Health Care During Pregnancy: A Survey Among Swiss Dentists. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2020, 18, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pa Costa, E.P.; Lee, J.Y.; Rozler, R.G.; Zeldin, L. Dental Care for Pregnant Women: An Assessment of North Carolina General Dentists. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2010, 141, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, K.; Salikhova, D.; Polyakova, M.; Zaytsev, A.; Egiazaryan, A.; Novozhilova, N. Knowledge and Attitude towards Probiotics among Dental Students and Teachers: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikheikina, A.; Novozhilova, N.; Polyakova, M.; Sokhova, I.; Mun, A.; Zaytsev, A.; Babina, K.; Makeeva, I. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice towards Chelating Agents in Endodontic Treatment among Dental Practitioners. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloetzel, M.K.; Huebner, C.E.; Milgrom, P.; Littell, C.T.; Eggertsson, H. Oral Health in Pregnancy: Educational Needs of Dental Professionals and Office Staff. J. Public Health Dent. 2012, 72, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes Vieira, D.R.; Figueiredo de Oliveira, A.E.; Ferreira Lopes, F.; de Figueiredo Lopes e Maia, M. Dentists’ Knowledge of Oral Health during Pregnancy: A Review of the Last 10 Years’ Publications. Community Dent. Health 2015, 32, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center. Oral Health Care During Pregnancy: A National Consensus Statement; National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Naseem, M.; Khurshid, Z.; Khan, H.A.; Niazi, F.; Zohaib, S.; Zafar, M.S. Oral Health Challenges in Pregnant Women: Recommendations for Dental Care Professionals. Saudi J. Dent. Res. 2016, 7, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krywko, D.M.; King, K.C. Aortocaval Compression Syndrome; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.R.; Wang, E. Prevention of Supine Hypotensive Syndrome in Pregnant Women Treated with Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 218, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, V.T.; Manigandan, T.; Sarumathi, T.; Aarthi Nisha, V.; Amudhan, A. Dental Considerations in Pregnancy—A Critical Review on the Oral Care. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Gupta, R.; Patthi, B.; Singla, A.; Pandita, V.; Kumar, J.; Malhi, R.; Vashishtha, V. Imaging More Imagining Less: An Insight into Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Regarding Radiation Risk on Pregnant Women among Dentists of Ghaziabad—A Cross Sectional Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, ZC20–ZC25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Brown, J.; Foschi, F.; Al-Nuaimi, N.; Fitton, J. A Survey of Cone Beam Computed Tomography Use amongst Endodontic Specialists in the United Kingdom. Int. Endod. J. 2025, 58, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppenberg, K.S.; Hill, D.A.; Miller, D.P. Safety of Radiographic Imaging during Pregnancy. Am. Fam. Physician 1999, 59, 1813–1818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yoon, I.; Slesinger, T.L. Radiation Exposure in Pregnancy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.M.; Shin, T.J. Use of Local Anesthetics for Dental Treatment during Pregnancy; Safety for Parturient. J. Dent. Anesth. Pain Med. 2017, 17, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urîtu, A.; Buciu, V.B.; Roi, C.; Chioran, D.; Serban, D.M.; Nicoleta, N.; Rusu, E.L.; Ionac, M.; Riviș, M.; Ciurescu, S. Review of the Safety and Clinical Considerations of Vasoconstrictor Agents in Dental Anesthesia During Pregnancy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Drug Safety Communication—Avoid Use of NSAIDs in Pregnancy at 20 Weeks or Later|FDA. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/nonsteroidal-anti-inflammatory-drugs-nsaids-drug-safety-communication-avoid-use-nsaids-pregnancy-20 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

| Sociodemographic Data | Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 40 (10.0) |

| Female | 363 (90.0) | |

| Age | Mean (SD) | 34.7 (10.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 33 (26; 40) | |

| Specialty | Conservative dentist | 173 (42.9) |

| Dental surgeon | 43 (10.7) | |

| Orthodontist | 72 (17.9) | |

| Prosthetic dentist | 14 (3.5) | |

| General dentist | 80 (19.9) | |

| Maxillo-facial surgeon | 4 (1.0) | |

| Other | 17 (4.2) | |

| Years of clinical experience | <2 | 80 (19.9) |

| 2–5 | 75 (18.6) | |

| 6–10 | 72 (17.9) | |

| 11–20 | 108 (26.8) | |

| 21–30 | 40 (9.9) | |

| >30 | 28 (6.9) | |

| <2 | 80 (19.9) |

| Sociodemographic Data | Knowledge (Maximum 20) | Attitude (Maximum 25) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| Total | 11.2 (2.7) | 11 (9; 13) | 19.5 (3.6) | 19 (17; 23) |

| Male | 9.3 (1.8) | 9 (9; 11) | 16.5 (2.5) | 16.5 (16; 17) |

| Female | 11.4 (2.8) | 11 (9; 13) | 19.8 (3.5) | 19 (17; 23) |

| Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared = 70.399, df = 6, p < 0.001 * | Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared = 34.359, df = 1, p < 0.001 * | |||

| Conservative dentist | 12.0 (2.6) | 12 (10; 14) a | 20.3 (3.7) | 20 (17; 24) a |

| Dental surgeon | 12.3 (2.3) | 12 (11; 14) a | 18.5 (2.5) | 19 (16; 19) ab |

| Orthodontist | 9.3 (2.0) | 9.5 (8; 10) b | 18.5 (3.2) | 18.5 (17; 21) b |

| Prosthetic dentist | 9.0 (2.1) | 8 (7.25; 11.25) c | 17.3 (3.4) | 16 (15.25; 17) b |

| General dentist | 11.0 (2.8) | 11 (9; 12) bc | 19.6 (3.7) | 20 (17; 23) ab |

| Maxillo-facial surgeon | 11 (0.0) | 11 (11; 11) abc | 19 (0.2) | 19 (18; 20) ab |

| Other | 10.9 (3.7) | 10 (9; 15) abc | 20.2 (4.6) | 20 (16; 25) ab |

| Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared = 22.139, df = 1, p < 0.001 * | Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared = 22.639, df = 6, p < 0.001 * | |||

| Years of clinical experience | ||||

| <2 | 11.5 (2.9) | 12 (9; 14) | 17.3 (3.0) | 17 (16; 19.25) a |

| 2–5 | 10.8 (2.9) | 10 (9; 13) | 18.9 (3.3) | 19 (16.5; 21) b |

| 6–10 | 11.2 (3.1) | 11 (9; 13) | 20.9 (3.0) | 20 (19; 23) c |

| 11–20 | 11.4 (2.3) | 12 (9; 13) | 20.7 (3.6) | 20 (18; 25) c |

| 21–30 | 11.3 (2.5) | 11 (10; 12) | 19.2 (3.7) | 18.5 (17; 23) abc |

| >30 | 10.7 (3.1) | 10 (8; 14) | 19.7 (3.9) | 20 (17; 24) bc |

| Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared = 4.6664, df = 5, p = 0.4579 | Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared = 54.418, df = 5, p < 0.001 * | |||

| Item | Variants | Answers, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency care can be provided to pregnant women throughout all stages of pregnancy. | Yes | 399 (99.0) |

| No | 4 (1.0) | |

| I don’t know | 0 (0) | |

| The optimal trimester to provide routine dental care for a pregnant patient is… | First | 12 (3.0) |

| Second | 359 (89.1) | |

| Third | 28 (6.9) | |

| I don’t know | 4 (1.0) | |

| Obstetricians should always be consulted prior to treating a pregnant woman. | Yes | 311 (77.2) |

| No | 84 (20.8) | |

| I don’t know | 8 (2.0) | |

| Pregnant women can safely receive routine preventive care throughout pregnancy. | Yes | 264 (65.5) |

| No | 123 (30.5) | |

| I don’t know | 16 (4.0) | |

| Pregnant women can safely receive periodontal care (scaling/root planning) throughout all stages of pregnancy. | Yes | 140 (34.7) |

| No | 207 (51.3) | |

| I don’t know | 56 (14.0) | |

| Active periodontitis may increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. | Yes | 300 (74.4) |

| No | 47 (11.6) | |

| I don’t know | 56 (14.0) | |

| Pregnant women can receive local anesthesia throughout all stages of pregnancy. | Yes | 276 (68.5) |

| No | 107 (26.5) | |

| I don’t know | 20 (5.00) | |

| What is the safest local anesthetic during pregnancy? | Mepivacaine | 139 (34.5) |

| Bupivacaine | 32 (7.9) | |

| Lidocaine | 36 (8.9) | |

| Articaine | 296 (73.4) | |

| It is unsafe to use a local anesthetic with a vasoconstrictor in pregnant patients. | Yes | 299 (74.2) |

| No | 80 (19.9) | |

| I don’t know | 24 (5.9) | |

| Pregnant women can safely receive dental radiographs throughout all stages of pregnancy. | Yes | 172 (42.7) |

| No | 203 (50.4) | |

| I don’t know | 28 (6.9) | |

| Administration of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs is contraindicated during pregnancy. | Yes | 143 (35.5) |

| No | 200 (49.6) | |

| I don’t know | 60 (14.9) | |

| Administration of antibiotics is contraindicated during pregnancy. | Yes | 135 (33.5) |

| No | 200 (49.6) | |

| I don’t know | 68 (16.9) | |

| What are the safest antibiotics during pregnancy? n = 200 * | Penicillins | 184 (92.0) |

| Macrolides | 52 (26.0) | |

| Tetracyclines | 0 (0) | |

| Flouroquinolones | 16 (8.0) | |

| Lincosamides | 16 (8.0) | |

| What are the alternative antibiotics for pregnant women allergic to penicillin? n = 200 * | Amoxicillin clavulanates | 64 (32.0) |

| Macrolides | 144 (72.0) | |

| Tetracyclines | 0 (0) | |

| Flouroquinolones | 32 (16.0) | |

| Lincosamides | 28 (14.0) | |

| Is metronidazole contraindicated during pregnancy? n = 200 * | Contraindicated during all stages of pregnancy | 140 (70.0) |

| Contraindicated in the first trimester | 80 (40.0) | |

| Contraindicated in the second trimester | 4 (2.0) | |

| Contraindicated in the third trimester | 4 (2.0) | |

| Metronidazole is safe during all stages of pregnancy | 40 (20.0) | |

| What is the right position in the dental unit in the third trimester of pregnancy? | Inclined to the left | 100 (24.8) |

| Inclined to the right | 72 (17.9) | |

| Supine position with legs slightly elevated | 40 (9.9) | |

| Regular position | 120 (29.8) | |

| No treatment should be provided during the third trimester of pregnancy | 71 (17.6) |

| Item | Timing of Safe NSAID Administration During Pregnancy n (%), n = 200 * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Trimester | 2nd Trimester | 3rd Trimester | Contraindicated | I Don’t Know | |

| Metamizole | 12 (6.0) | 44 (22.0) | 28 (14.0) | 108 (54.0) | 28 (14.0) |

| Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) | 8 (4.0) | 52 (26.0) | 40 (20.0) | 104 (52.0) | 24 (12.0) |

| Ketoprofen | 12 (6.0) | 52 (26.0) | 20 (10.0) | 92 (46.0) | 40 (20.0) |

| Ketorolac | 12 (6.0) | 40 (20.0) | 20 (10.0) | 100 (50.0) | 40 (20.0) |

| Nimesulide | 8 (4.0) | 56 (28.0) | 28 (14.0) | 88 (44.0) | 44 (22.0) |

| Ibuprofen | 76 (38.0) | 144 (72.0) | 76 (38.0) | 20 (10.0) | 24 (12.0) |

| Acetaminophen | 88 (44.0) | 160 (80.0) | 120 (60.0) | 12 (16.0) | 16 (18.0) |

| Item | Respondents’ Answers n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | N | D | SD | |

| Maintaining oral health during pregnancy is important. | 360 (89.3) | 27 (6.7) | 8 (2.0) | 4 (1.0) | 4 (1.0) |

| Oral health checkup should be a routine component of monitoring pregnant patients. | 363 (90.0) | 16 (4.0) | 16 (4.0) | 8 (2.0) | 0 (0) |

| Pregnant women should receive only emergency dental care. | 64 (15.9) | 51 (12.7) | 108 (26.8) | 48 (11.9) | 132 (32.7) |

| I do not feel comfortable treating pregnant women. | 76 (18.85) | 76 (18.85) | 95 (23.6) | 44 (10.9) | 112 (27.8) |

| I prefer not to treat pregnant women. | 51 (12.7) | 52 (12.9) | 120 (29.8) | 32 (7.9) | 148 (36.7) |

| Item | Variants | Answers, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Do you treat pregnant patients? | Yes | 336 (83.4) |

| No | 67 (16.6) | |

| Why do you not provide dental care to pregnant women? n = 67 * | Do not feel I have enough knowledge | 16 (23.8) |

| I have no pregnant patients | 35 (52.2) | |

| Do not feel comfortable treating pregnant patients | 12 (17.9) | |

| I have liability concerns treating pregnant patients | 28 (41.8) | |

| How often do you provide dental treatments to pregnant patients? n = 336 * | At least once a month | 44 (13.2) |

| Once every 2 months | 72 (21.4) | |

| Once every 6 months | 120 (35.7) | |

| Once every 12 months | 24 (7.1) | |

| Rarer than once every 12 months | 76 (22.6) | |

| Do you always advise pregnant women on oral health irrespective of the reason of visit? n = 336 * | Yes | 263 (78.3) |

| In high risk patients | 32 (9.5) | |

| No | 41 (12.2) | |

| Based on your practice, what are the most common reasons for visiting dentists during pregnancy? n = 336 * | Enamel erosion | 4 (1.2) |

| Dentin hypersensitivity | 62 (16.0) | |

| Oral mucosa diseases | 64 (19.0) | |

| Gingivitis | 144 (42.9) | |

| Caries | 148 (44.0) | |

| Apical periodontitis | 48 (13.1) | |

| Pulpitis | 164 (48.8) | |

| Other | 92 (27.4) | |

| Which anesthetics do you use in pregnant women? n = 336 * | Articaine | 281 (83.6) |

| Mepivacaine | 44 (13.1) | |

| Lidocaine | 18 (5.4) | |

| Do not use anesthesia | 9 (2.7) | |

| Do you prescribe antibiotics to pregnant women? n = 336 * | Yes | 56 (16.7) |

| No | 280 (83.3) | |

| Which antibiotics do you prescribe to pregnant women? n = 336 * | Penicillin + beta-lactamase inhibitors | 32 (57.2) |

| Penicillins | 12 (21.4) | |

| Macrolides | 8 (14.3) | |

| Other | 4 (7.1) | |

| Are you interested in receiving additional information to enhance your knowledge on treating pregnant patients? | Yes, I would like to attend an offline workshop or seminar | 12 (3.0) |

| Yes, I would like to attend an online course (webinar) | 259 (64.3) | |

| I would like to receive information from articles/education brochures/books | 264 (65.5) | |

| No, I think I have enough knowledge on treating pregnant patients | 16 (4.0) |

| Item | Dental Care Procedures Provided by the Dentists During Pregnancy and Their Timing (n = 336), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Trimester | 2nd Trimester | 3rd Trimester | Did Not Provide This Particular Procedure | |

| Anesthesia | 108 (32.1) | 232 (69.0) | 128 (38.1) | 76 (22.6) |

| Radiography | 32 (9.5) | 120 (35.7) | 52 (15.5) | 196 (58.3) |

| Routine prophylaxis | 128 (38.1) | 208 (61.9) | 120 (35.7) | 84 (25.0) |

| Periodontal care (scaling and root planning) | 16 (4.76) | 52 (15.5) | 36 (10.7) | 272 (80.1) |

| Teeth extractions | 40 (11.9) | 76 (22.6) | 56 (16.7) | 236 (70.2) |

| Root canal treatment | 72 (21.4) | 172 (51.2) | 100 (29.8) | 128 (38.1) |

| Emergency surgery | 44 (13.1) | 76 (22.6) | 48 (14.3) | 240 (71.4) |

| Routine surgery | 4 (1.2) | 48 (14.3) | 20 (6.0) | 272 (80.1) |

| Prosthetic treatment (removable dentures) | 0 (0) | 20 (6.0) | 12 (3.6) | 304 (90.5) |

| Prosthetic treatment (fixed dentures) | 0 (0) | 16 (4.8) | 12 (3.6) | 308 (91.7) |

| Orthodontic treatment (initiation) | 12 (3.6) | 28 (8.3) | 12 (3.6) | 292 (86.9) |

| Orthodontic treatment (in progress) | 48 (14.3) | 48 (14.3) | 40 (11.9) | 256 (76.2) |

| Restorative treatment (emergency) | 136 (40.5) | 212 (63.1) | 120 (35.7) | 88 (26.2) |

| Esthetic teeth restoration | 76 (22.6) | 152 (45.2) | 76 (22.6) | 156 (46.4) |

| Teeth bleaching | 0 (0) | 12 (3.6) | 16 (4.8) | 300 (89.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Babina, K.; Polyakova, M.; Makeeva, I.; Sokhova, I.; Mikheikina, A.; Zaytsev, A.; Novozhilova, N. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Towards Treating Pregnant Patients Among Dental Professionals in Russia. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13100457

Babina K, Polyakova M, Makeeva I, Sokhova I, Mikheikina A, Zaytsev A, Novozhilova N. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Towards Treating Pregnant Patients Among Dental Professionals in Russia. Dentistry Journal. 2025; 13(10):457. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13100457

Chicago/Turabian StyleBabina, Ksenia, Maria Polyakova, Irina Makeeva, Inna Sokhova, Anna Mikheikina, Alexandr Zaytsev, and Nina Novozhilova. 2025. "Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Towards Treating Pregnant Patients Among Dental Professionals in Russia" Dentistry Journal 13, no. 10: 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13100457

APA StyleBabina, K., Polyakova, M., Makeeva, I., Sokhova, I., Mikheikina, A., Zaytsev, A., & Novozhilova, N. (2025). Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Towards Treating Pregnant Patients Among Dental Professionals in Russia. Dentistry Journal, 13(10), 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj13100457