Variations in Some Features of Oral Health by Personality Traits, Gender, and Age: Key Factors for Health Promotion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instruments for Data Collection

2.1.1. Simplified Oral Hygiene Index (OHI-S)

2.1.2. Caries Experience (DMFT Index)

2.1.3. Physical Examination of the Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

2.2. Identification of Parafunctional Habits

2.2.1. Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP)

2.2.2. Courtauld Emotional Control Suppression Scale (CECS)

2.3. Big Five Inventory

2.3.1. Data Analyses

2.3.2. Regression Analysis

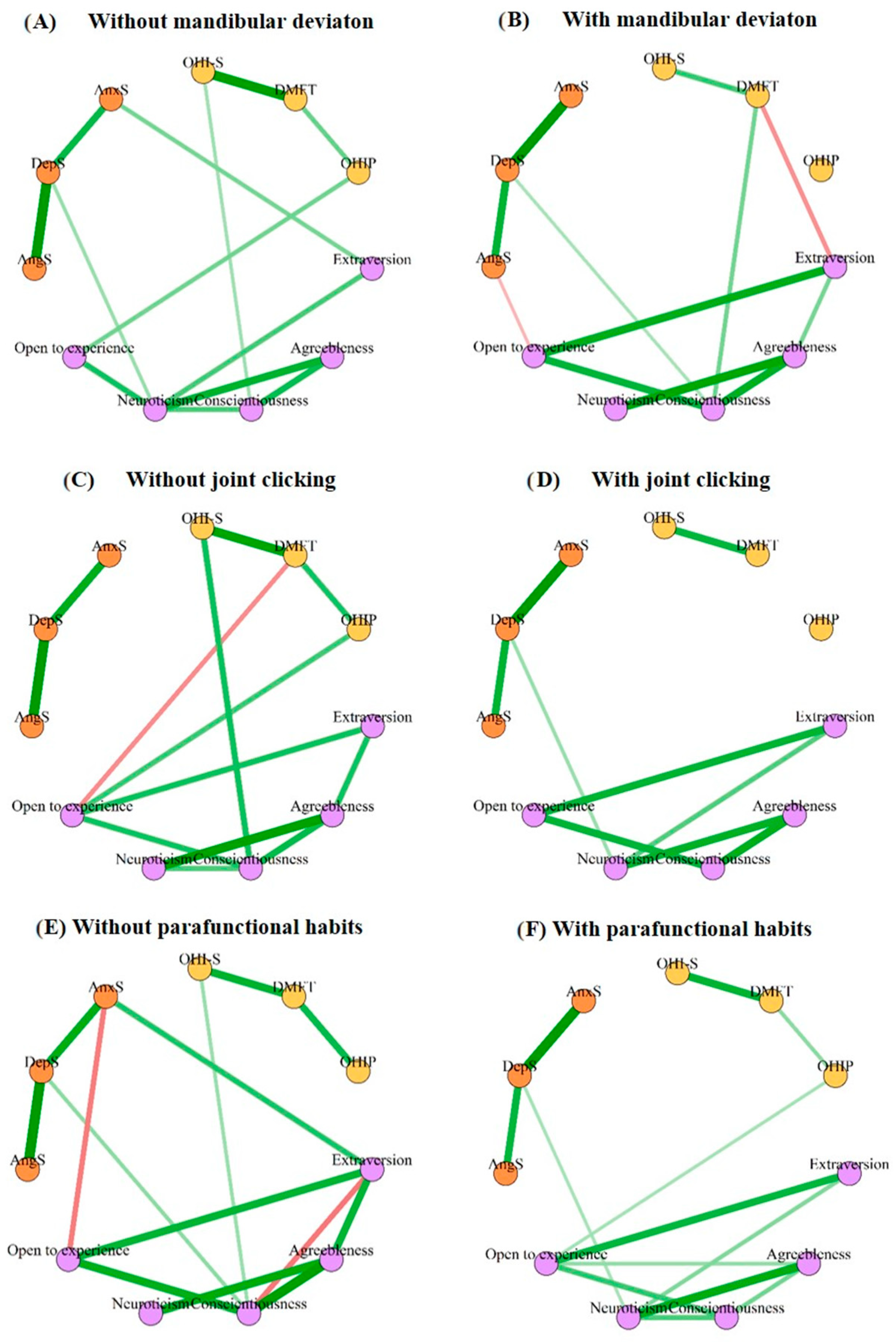

2.3.3. Network Analyses

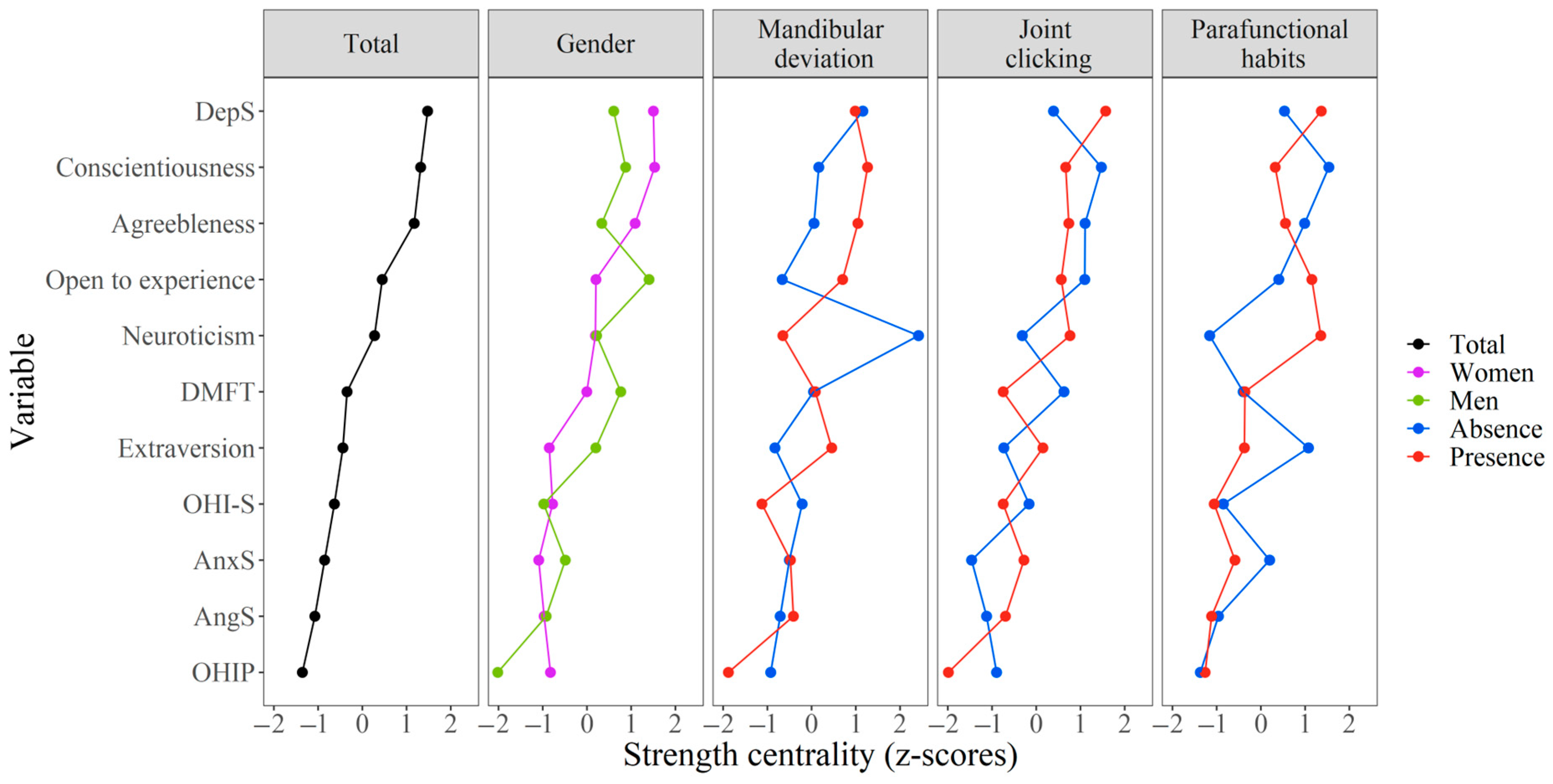

2.3.4. Centrality Analysis

2.3.5. Network Accuracy and Stability

2.4. Comparisons Between Networks

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Population

3.2. Oral Health Conditions

3.3. Self-Perception of Oral Health

3.4. Personality Traits

3.5. Emotional Suppression

Relationship of Oral Health Conditions with Personality Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030; WHO: Ginebra, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, A.; Kawamura, M. Involvement of psychosocial factors in the association of obesity with periodontitis. J. Oral Sci. 2010, 52, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barranca-Enríquez, A.; Romo-González, T. Your health is in your mouth: A comprehensive view to promote general wellness. Front. Oral Health 2022, 3, 971223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas Alcayaga, G.; Misrachi Launert, C. La interacción paciente-dentista, a partir del significado psicológico de la boca. Av. Odontoestomatol. 2004, 20, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshram, S.; Gattani, D.; Shewale, A.; Bodele, S. Association of Personality Traits with Oral Health Status: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2017, 4, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, W.M.; Caspi, A.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E.; Broadbent, J.M. Personality and oral health. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 119, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A.; Roberts, B.; Shiner, R. Personality development: Stability and change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 453–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosania, A. Estrés, la depresión, cortisol, y enfermedad periodontal. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, E. La caries dental y cambios en la ansiedad en la adolescencia tardía. Community Dent. Epidemiol. Oral 1998, 26, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavagal, P.; Singla, H. Prevalence of dental caries based on personality types of 35–44 years old residents in Davangere city. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2017, 7, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divaris, K.; Lee, J.Y.; Baker, A.D.; Gizlice, Z.; Rozier, R.G.; DeWalt, D.A.; Vann, W.F., Jr. Influence of caregivers and children’s entry into the dental care system. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e1268–e1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaría de Salud; Subsecretaría de Prevención y Promoción de la Salud; Dirección General de Epidemiología. Resultados del Sistema de Vigilancia Epidemiológica de Patologías Bucales SIVEPAB; Secretaría de Salud: Mexico City, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Omiri, M.K.; Alhijawi, M.M.; Al-Shayyab, M.H.; Kielbassa, A.M.; Lynch, E. Relationship between dental students’ personality profiles and self-reported oral health behaviour. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2019, 17, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, S.C.; Vermillion, J.R. The Simplified Oral Hygiene Index. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1964, 68, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nithila, A.; Bourgeois, D.; Barmes, D.E.; Murtomaa, H. Banco Mundial de Datos sobre Salud Bucodental de la OMS, 1986–1996: Panorámica de las encuestas de salud bucodental a los 12 años de edad. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 1998, 4, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeson Jeffrey, P. Oclusión y Afecciones Temporomandibulares 5ta. Edición; Mosby, Co.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Atsü, S.S.; Güner, S.; Palulu, N.; Bulut, A.C.; Kürkçüoğlu, I. Parafunciones orales, rasgos de personalidad, ansiedad y su asociación con signos y síntomas de los trastornos temporomandibulares en los adolescentes. Cienc. Salud Afr. 2019, 19, 1801–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, N.F.; Allen, P.F.; Abu-bakr, N.H.; Abdel-Rahman, M.E. Psychometric properties and performance of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14s-ar) among Sudanese adults. J. Oral Sci. 2013, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, J.; Sumano, O.; Sifuentes, M.C.; Aguilar, A. Impacto de la salud bucal en la calidad de vida de adultos mayores demandantes de atención dental. Univ. Odontol. 2010, 29, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Castrejón-Pérez, R.C.; Borges-Yáñez, S.A.; Irigoyen-Camacho, M.E. Validación de un instrumento para medir el efecto de la salud bucal en la calidad de vida de adultos mayores mexicanos. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2010, 27, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durá, E.; Andreu, Y.; Galdón, M.J.; Ibáñez, E.; Pérez, S.; Ferrando, M.; Murgui, S.; Martínez, P. Emotional Suppression and Breast Cancer: Validation Research on the Spanish Adaptation of the Courtauld Emotional Control Scale (CECS). Span. J. Psychol. 2010, 13, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Donahue, E.M.; Kentle, R.L. The Big Five Inventory Versions 4a and 54; Institute of Personality and Social Research: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chavira Trujillo, G.; Celis de la Rosa, A. Propiedades Psicométricas del Inventario de los Cinco Factores de Personalidad (BFI) en Población Mexicana. Acta Investig. Psicol. 2021, 11, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.; Waldorp, L.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Borsboom, D. Qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Borkulo, C.D.; Boschloo, L.; Borsboom, D.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Waldorp, L.J.; Schoevers, R.A. Association of symptom network structure with the course of depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Xi, H.T.; An, F.; Wang, Z.; Han, L.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Q.; Bai, W.; Zhao, Y.J.; Chen, L.; et al. The association between internet addiction and anxiety in nursing students: A network analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 723355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J. Networks: An Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp, S.; Maris, G.; Waldorp, L.J.; Borsboom, D. Network psychometrics. In Handbook of Psychometrics; Irwing, P., Hughes, D., Booth, T., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.02818 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- van Borkulo, C.D.; van Bork, R.; Boschloo, L.; Kossakowski, J.J.; Tio, P.; Schoevers, R.A.; Borsboom, D.; Waldorp, L.J. Comparing network structures on three aspects: A permutation test. Psychol. Methods 2022, 28, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedos, C.; Apelian, N.; Vergnes, J.N. Towards a biopsychosocial approach in dentistry: The montreal-toulouse model. Br. Dent. J. 2020, 228, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerman, M.; Mouradian, W.E. Integrating oral and systemic. Health: Innovations in transdisciplinary science, health care and policy. Front. Dent. Med. 2020, 1, 599214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasneh, J.; Al-Omiri, M.K.; Al-Hamad, K.Q.; Al Quran, F.A. Relación entre la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud bucal de los pacientes, la satisfacción con la dentición y los perfiles de personalidad. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2009, 10, E049–E056. [Google Scholar]

- Rendón Alvarado, A.; Gonzales Fuentes, J.R.; Heredia, C.R. Prevalencia de facetas de desgaste dentario asociado a personalidad en estudiantes universitarios peruanos. KIRU 2013, 10, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Benítez, M. Mecanismos de relación entre la personalidad y los procesos de salud-enfermedad. Rev. Psicol. Univ. Antioq. 2015, 7, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penacoba, C.; González, M.J.; Santos, N.; Romero, M. Predictores psicosociales del afecto en pacientes adultos en tratamiento de ortodoncia. Eur. J. Orthod. 2014, 36, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachalov, V.V.; Orekhova, L.Y.; Isaeva, E.R.; Kudryavtseva, T.V.; Loboda, E.S.; Sitkina, E.V. Characteristics of dental patients determining their compliance level in dentistry: Relevance for predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine. EPMA J. 2018, 9, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadet Sağlam, A.; Sibel, G.; Nilgün, P.; Ali Can, B.; Işın, K. Oral parafunctions, personality traits, anxiety and their association with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in the adolescents. Afr. Health Sci. 2019, 19, 1801–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Laak, J. Las cinco grandes dimensiones de la personalidad. Revista de Psicología de la PUCP 1996, 14, 129–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, G.; Rappersberger, K.; Rausch-Fan, X.H.; Bruckmann, C.; Hofmann, E. Effect of personality traits on the oral health-related quality of life in patients with oral lichen planus undergoing treatment. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 2381–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Shetty, N. Association between dental caries, periodontal status, and personality traits of 35–44-year-old adults in Bareilly City, Uttar Pradesh, India. J. Indian Assoc. Public Health Dent. 2019, 17, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakershahrak, M.; Brennan, D. Personality traits and income inequalities in self-rated oral and general health. Eur. J. Ora. Sci. 2022, 130, e12893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A.F.; Albesher, N.; Aljohani, M.; Alsinanni, M.; Turkistani, O.; Salam, M. Association of oral parafunctional habits with anxiety and the Big-Five Personality Traits in the Saudi adult population. Saudi Dent. J. 2021, 33, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, L. The importance of the repressive coping style: Findings from 30 years of research. Anxiety Stress Coping 2009, 23, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo-González, T.; Martínez, A.; Hernández, M.R.; Gutiérrez, G.; Larralde, C. Psychological Features of Breast Cancer in Mexican Women I: Personality Traits and Stress Symptoms. Adv. Neuroimmune Biol. 2018, 7, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anarte, M.T.; López, A.E.; Ramírez Maestre, C.; Esteve Zarazaga, R. Evaluación Del Patrón De Conducta Tipo C En Pacientes Crónicos. An. Psicol. 2000, 16, 133–141. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/analesps/article/view/29271 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Giese-Davis, J.; Spiegel, D. Suppression, repressive-defensiveness, restraint, and distress in metastatic breast cancer: Separable or inseparable constructs? J. Pers. 2001, 69, 417–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslamipour, F.; Borzabadi-Farahani, A.; Asgari, I. The relationship between aging and oral health inequalities assessed by the DMFT index. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2010, 11, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Divaris, K. The ethical imperative of addressing oral health disparities: A unifying framework: A unifying framework. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.; Ye, Y.; Ye, S.; Wang, L.; Du, W.; Yao, L.; Guo, J. Effect of personality on oral health-related quality of life in undergraduates. Angle Orthod. 2018, 88, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, N.; Glogauer, M.; Tenenbaum, H.; Siddiqi, A.; Quiñonez, C. Social-biological interactions in oral disease: A ‘cells to society’ view. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Age Range | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Diseases | Total (n = 184) | Women (n = 110) | Men (n = 74) | 18–20 (n = 35) | 21–40 (n = 89) | 41–60 (n = 43) | Over 60 (n = 17) | |||||||

| Non-Carious Lesions | f | % | f | % | f | % | f | % | f | % | f | % | f | % |

| Attrition | 161 | 87.50% | 98 | 89.09% | 63 | 85.13% | 23 | 65.71% | 82 | 92.13% | 40 | 93.02% | 16 | 94.11% |

| No injury | 21 | 11.41% | 12 | 10.90% | 9 | 12.16% | 12 | 34.28% | 7 | 7.86% | 2 | 4.65% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Abrasion | 7 | 3.80% | 3 | 2.72% | 4 | 5.40% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 3.37% | 1 | 2.32% | 3 | 17.64% |

| Abfraction | 4 | 2.17% | 0 | 0.00% | 4 | 5.40% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 4 | 9.30% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Erosion | 2 | 1.08% | 1 | 0.90% | 1 | 1.35% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 1.12 | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 5.88% |

| Maximum opening | ||||||||||||||

| Normal +40 mm | 176 | 95.65% | 102 | 92.72% | 74 | 100% | 33 | 94.28% | 84 | 94.38% | 42 | 97.67% | 17 | 100% |

| Limitation −40 mm | 8 | 4.34% | 8 | 7.27% | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 5.71% | 5 | 5.61% | 1 | 2.32% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Mandibular deviation | ||||||||||||||

| With deviation | 117 | 63.58% | 71 | 64.54% | 46 | 62.16% | 19 | 54.28% | 53 | 59.55% | 32 | 74.41% | 13 | 76.47% |

| No deviation | 67 | 36.41% | 39 | 35.45% | 28 | 37.83% | 16 | 45.71% | 36 | 40.44% | 11 | 25.58% | 4 | 23.52 |

| Joint clicking | ||||||||||||||

| With noise | 92 | 50.00% | 56 | 50.90% | 36 | 48.64% | 12 | 34.28% | 44 | 49.43% | 27 | 62.79% | 9 | 52.94% |

| Without noise | 92 | 50.00% | 54 | 49.09% | 38 | 51.35% | 23 | 65.71% | 45 | 50.56% | 16 | 37.20% | 8 | 47.05% |

| Parafunctional habits | ||||||||||||||

| No habit | 63 | 34.24% | 37 | 33.63% | 26 | 35.13% | 11 | 31.42% | 26 | 29.21% | 18 | 41.86% | 8 | 47.05% |

| Onychophagia | 83 | 45.10% | 49 | 44.54% | 34 | 45.94% | 22 | 62.85% | 44 | 49.43% | 12 | 27.90% | 5 | 29.41% |

| Mouth breathing | 44 | 23.91% | 27 | 24.54% | 17 | 22.97% | 9 | 25.71% | 20 | 22.47% | 11 | 25.58% | 4 | 23.52% |

| Bruxism | 32 | 17.39% | 17 | 15.45% | 15 | 20.27% | 6 | 17.14% | 17 | 19.10% | 8 | 18.60% | 1 | 5.88% |

| Digital suction | 4 | 2.17% | 3 | 2.72% | 1 | 1.35% | 0 | 0.00% | 4 | 4.49% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Atypical swallowing | 1 | 0.54% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 1.35% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 1.12% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Gender | p | Age Range | p | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Total | Women | Men | 18–20 | 21–40 | 41–60 | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| OHI-S | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.28 a | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.59 | 0.65 | 1.16 | 0.99 | <0.01 b |

| DMFT | 9.98 | 5.40 | 10.00 | 5.60 | 9.95 | 5.13 | 0.98 a | 7.80 | 5.39 | 8.20 | 4.55 | 13.53 | 3.91 | <0.01 b |

| OHIP | 14.34 | 9.43 | 15.20 | 10.20 | 13.05 | 8.05 | 0.18 a | 13.74 | 9.67 | 13.10 | 9.79 | 16.33 | 9.22 | 0.10 b |

| Extraversion | 28.67 | 4.31 | 28.84 | 4.47 | 28.43 | 4.09 | 0.48 a | 27.49 | 5.16 | 28.54 | 3.45 | 29.74 | 5.00 | 0.09 b |

| Agreeableness | 29.95 | 4.46 | 30.21 | 4.53 | 29.57 | 4.35 | 0.22 a | 29.06 | 3.74 | 30.20 | 4.26 | 30.26 | 5.09 | 0.47 b |

| Conscientiousness | 32.61 | 4.44 | 32.54 | 4.39 | 32.73 | 4.55 | 0.84 a | 32.26 | 4.67 | 33.17 | 3.64 | 32.42 | 4.78 | 0.37 b |

| Neuroticism | 27.73 | 4.16 | 28.06 | 4.33 | 27.24 | 3.88 | 0.21 a | 26.60 | 4.35 | 28.01 | 3.86 | 28.49 | 4.31 | 0.13 b |

| Open to experience | 37.21 | 5.15 | 36.58 | 5.07 | 38.15 | 5.14 | 0.06 a | 35.86 | 5.17 | 37.29 | 4.76 | 38.30 | 5.10 | 0.16 b |

| Anger S. | 17.79 | 3.78 | 18.07 | 3.96 | 17.38 | 3.49 | 0.25 a | 17.74 | 3.88 | 17.87 | 3.59 | 17.53 | 3.88 | 0.84 b |

| Depression S. | 18.41 | 3.96 | 18.09 | 3.81 | 18.89 | 4.15 | 0.3 a | 18.20 | 4.03 | 18.31 | 3.69 | 18.81 | 4.41 | 0.90 b |

| Anxiety S. | 18.31 | 3.57 | 17.82 | 3.59 | 19.04 | 3.44 | 0.06 a | 18.63 | 3.81 | 18.35 | 3.71 | 18.16 | 3.54 | 0.92 b |

| Emotional Suppression | 54.51 | 9.09 | 53.98 | 9.25 | 55.31 | 8.88 | 0.47 a | 54.57 | 9.51 | 54.53 | 8.80 | 54.51 | 9.41 | 0.98 b |

| DMFT (R2 = 0.30) | OHI-S (R2 = 0.22) | OHIP (R2 = 0.14) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Β | EE | T | Β | EE | t | β | EE | t |

| Intercept | 0.48 | 11.84 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 1.09 | 2.53 | 1.07 | 2.37 |

| Gender | −0.51 | 0.74 | −0.69 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.81 | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.84 |

| Age | 13.84 | 1.87 | 7.40 *** | 0.35 | 0.06 | 5.78 *** | 0.62 | 0.17 | 3.70 *** |

| Extroversion | 12.16 | 5.97 | 2.04 * | −0.11 | 0.19 | −0.57 | −0.11 | 0.54 | −0.20 |

| Agreeableness | −10.90 | 7.19 | −1.51 | −0.13 | 0.23 | −0.55 | −0.12 | 0.65 | −0.19 |

| Conscientiousness | −5.40 | 7.68 | −0.70 | −0.49 | 0.25 | −1.99 * | 1.80 | 0.69 | 2.58 * |

| Neuroticism | −4.15 | 6.79 | −0.61 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 1.05 | −0.78 | 0.61 | −1.28 |

| Open to experience | 3.49 | 7.09 | 0.49 | −0.09 | 0.23 | −0.41 | −1.92 | 0.64 | −2.99 ** |

| AngS | −1.88 | 4.36 | −0.43 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.44 | −0.88 | 0.39 | −2.22 * |

| DepS | −0.03 | 4.71 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.49 | −0.23 | 0.43 | −0.53 |

| AnxS | −0.95 | 4.85 | −0.19 | −0.01 | 0.16 | −0.05 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 1.42 |

| NCCL | MD | JC | PH | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | EE | z | β | EE | z | β | EE | z | Β | EE | z |

| Intercept | 4.90 | 3.19 | 1.53 | 0.78 | 1.82 | 0.43 | 2.01 | 1.74 | 1.15 | 2.30 | 1.89 | 1.22 |

| Gender | −0.10 | 0.54 | −0.19 | −0.19 | 0.35 | −0.55 | −0.17 | 0.33 | −0.50 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.85 |

| Age | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.71 * | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.05 * | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.30 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −1.65 |

| Extroversion | 0.10 | 0.08 | 1.38 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.26 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.22 |

| Agreeableness | −0.11 | 0.09 | −1.21 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 1.66 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.40 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 2.06 * |

| Conscientiousness | −0.10 | 0.08 | −1.23 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.91 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.67 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.07 |

| Neuroticism | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.66 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.75 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.93 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.37 |

| Open to experience | −0.08 | 0.06 | −1.27 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −1.46 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −1.58 | −0.10 | 0.04 | −2.40 * |

| AngS | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.14 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −1.54 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.83 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| DepS | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.32 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.03 |

| AnxS | −0.10 | 0.09 | −1.11 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.32 | −0.08 | 0.06 | −1.43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuentes, A.M.; Romo-González, T.; Huesca-Domínguez, I.; Campos-Uscanga, Y.; Barranca-Enríquez, A. Variations in Some Features of Oral Health by Personality Traits, Gender, and Age: Key Factors for Health Promotion. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120391

Fuentes AM, Romo-González T, Huesca-Domínguez I, Campos-Uscanga Y, Barranca-Enríquez A. Variations in Some Features of Oral Health by Personality Traits, Gender, and Age: Key Factors for Health Promotion. Dentistry Journal. 2024; 12(12):391. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120391

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuentes, Allexey Martínez, Tania Romo-González, Israel Huesca-Domínguez, Yolanda Campos-Uscanga, and Antonia Barranca-Enríquez. 2024. "Variations in Some Features of Oral Health by Personality Traits, Gender, and Age: Key Factors for Health Promotion" Dentistry Journal 12, no. 12: 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120391

APA StyleFuentes, A. M., Romo-González, T., Huesca-Domínguez, I., Campos-Uscanga, Y., & Barranca-Enríquez, A. (2024). Variations in Some Features of Oral Health by Personality Traits, Gender, and Age: Key Factors for Health Promotion. Dentistry Journal, 12(12), 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120391