Dental Practitioners’ Knowledge and Attitudes Toward the Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Peri-Implantitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Size Determination

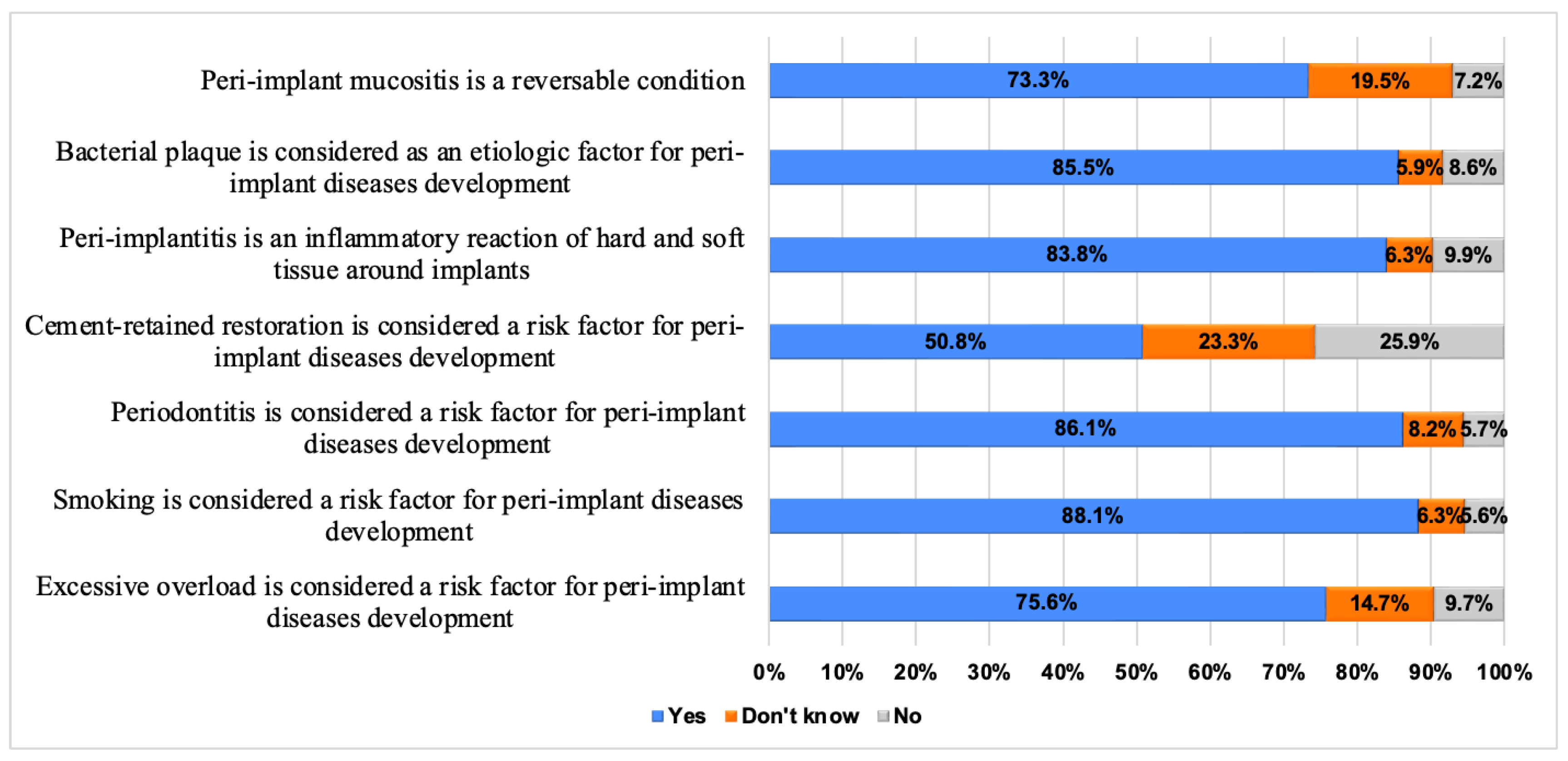

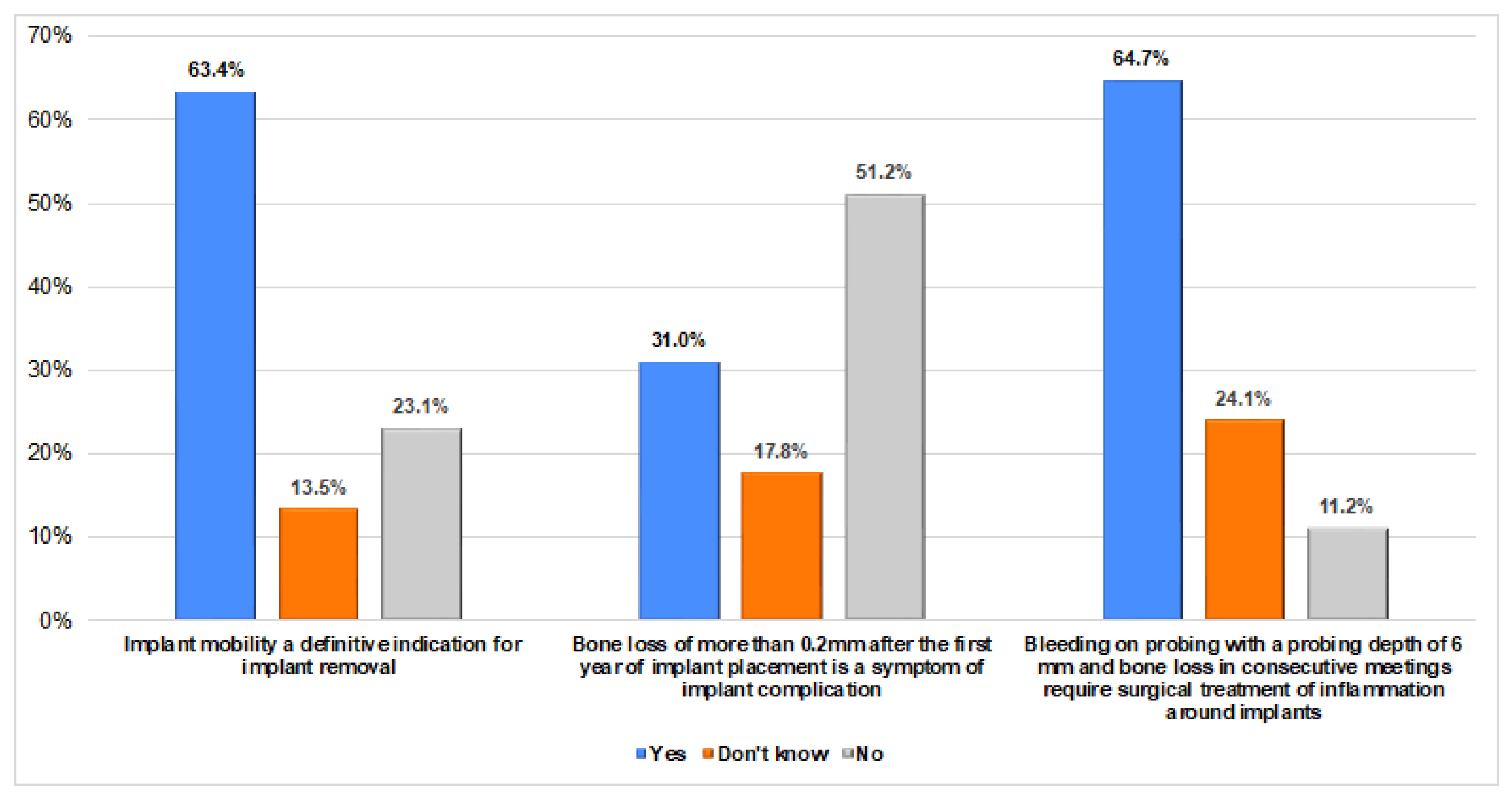

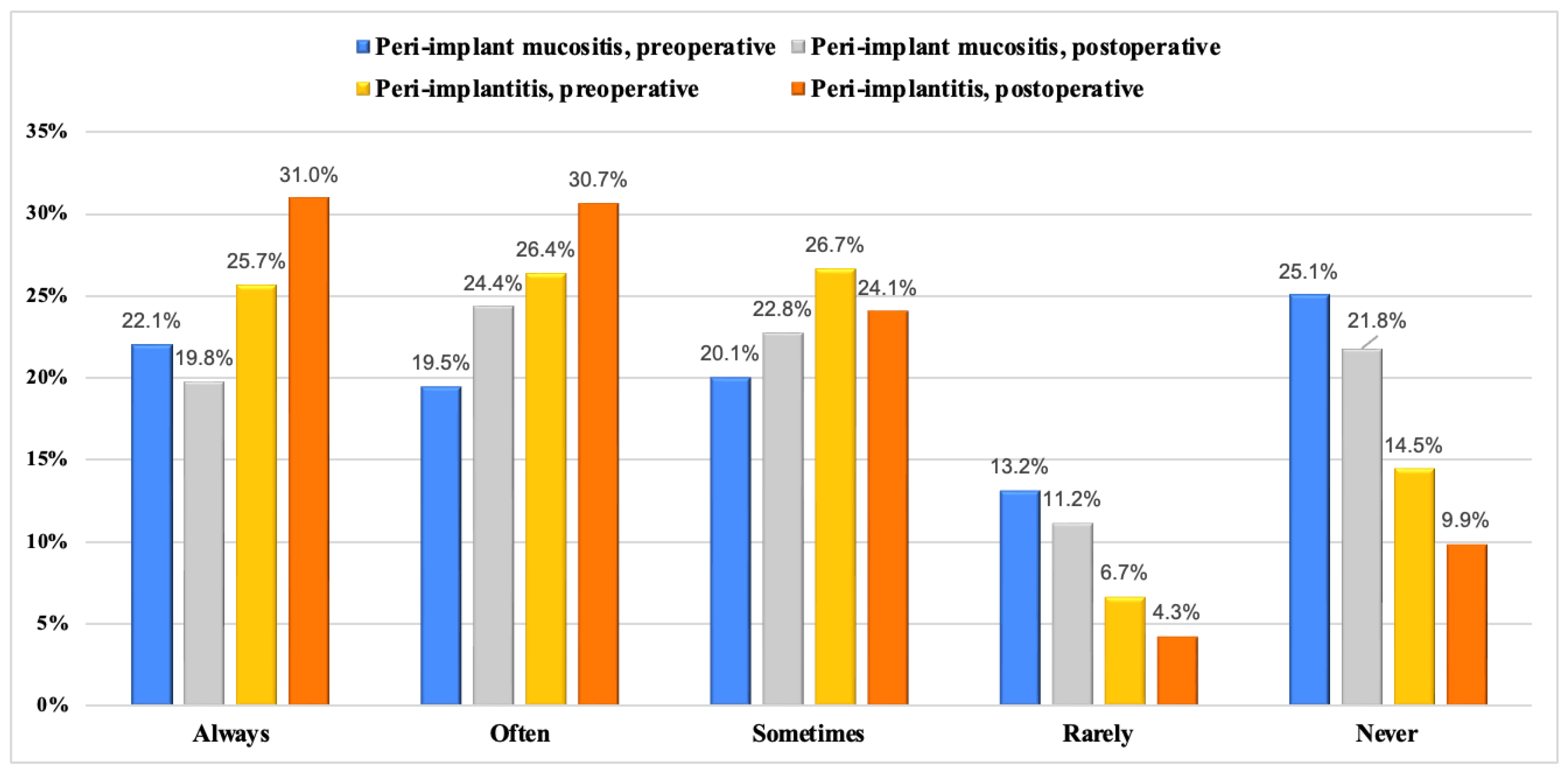

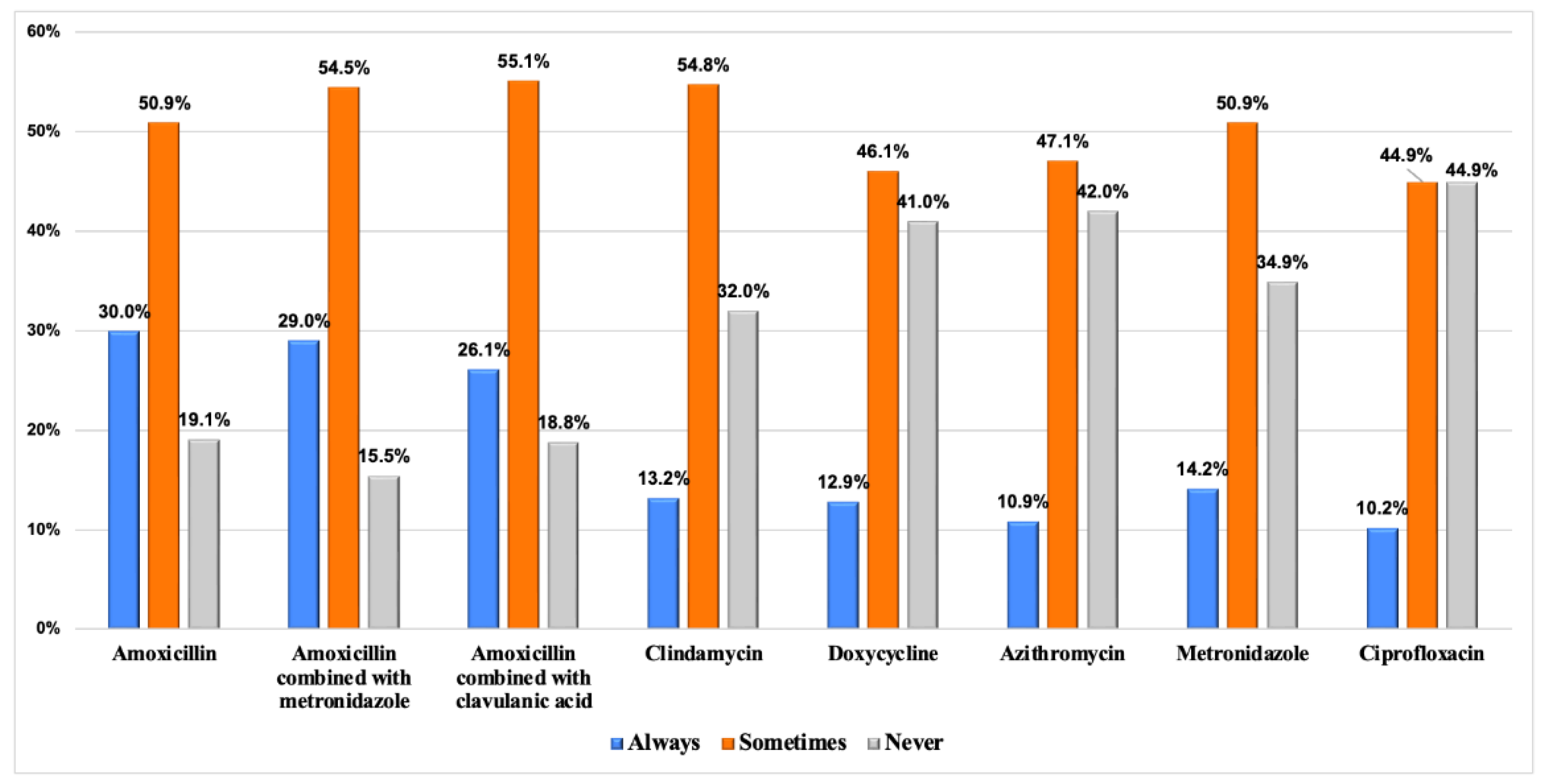

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lang, N.P.; Berglundh, T. Working Group 4 of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. Periimplant Diseases: Where Are We Now?–Consensus of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Chapple, I.L. Working Group 4 of the VIII European Workshop on Periodontology. Clinical Research on Peri-implant Diseases: Consensus Report of Working Group 4. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, S.; Berglundh, T.; Genco, R.; Aass, A.M.; Demirel, K.; Derks, J.; Figuero, E.; Giovannoli, J.L.; Goldstein, M.; Lambert, F. Primary Prevention of Peri-implantitis: Managing Peri-implant Mucositis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, S152–S157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhe, J.; Meyle, J.; Group D of the European Workshop on Periodontology. Peri-implant Diseases: Consensus Report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Derks, J.; Monje, A.; Wang, H. Peri-implantitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S246–S266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokaya, D.; Srimaneepong, V.; Wisitrasameewon, W.; Humagain, M.; Thunyakitpisal, P. Peri-Implantitis Update: Risk Indicators, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Eur. J. Dent. 2020, 14, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglundh, T.; Armitage, G.; Araujo, M.G.; Avila-Ortiz, G.; Blanco, J.; Camargo, P.M.; Chen, S.; Cochran, D.; Derks, J.; Figuero, E. Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions: Consensus Report of Workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S313–S318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanauskaite, A.; Becker, K.; Juodzbalys, G.; Schwarz, F. Clinical Outcomes Following Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implantitis at Grafted and Non-Grafted Implant Sites: A Retrospective Analysis. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2018, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romandini, M.; Berglundh, J.; Derks, J.; Sanz, M.; Berglundh, T. Diagnosis of Peri-implantitis in the Absence of Baseline Data: A Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2021, 32, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje, A.; Caballé-Serrano, J.; Nart, J.; Peñarrocha, D.; Wang, H.; Rakic, M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Clinical Parameters to Monitor Peri-implant Conditions: A Matched Case-control Study. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, G.; Signoriello, A.; Marincola, M.; Bonfante, E.A.; Díaz-Caballero, A.; Tomizioli, N.; Pardo, A.; Zangani, A. Five-Year Follow-Up of 8 and 6 Mm Locking-Taper Implants Treated with a Reconstructive Surgical Protocol for Peri-Implantitis: A Retrospective Evaluation. Prosthesis 2023, 5, 1322–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coli, P.; Jemt, T. Are Marginal Bone Level Changes around Dental Implants Due to Infection? Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2021, 23, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berglundh, T.; Jepsen, S.; Stadlinger, B.; Terheyden, H. Peri-implantitis and Its Prevention. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2019, 30, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, G.E.; Stähli, A.; Imber, J.; Sculean, A.; Roccuzzo, A. Physiopathology of Peri-implant Diseases. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2023, 25, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renvert, S.; Persson, G.R.; Pirih, F.Q.; Camargo, P.M. Peri-implant Health, Peri-implant Mucositis, and Peri-implantitis: Case Definitions and Diagnostic Considerations. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S278–S285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadkhodazadeh, M.; Hosseinpour, S.; Kermani, M.E.; Amid, R. Knowledge and Attitude of Iranian Dentists towards Peri-Implant Diseases. J. Adv. Periodontol. Implant Dent. 2018, 9, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.; Vasudevan, S.; Palle, A.R.; Gedela, R.K.; Punj, A.; Vaishnavi, V. Awareness and Management of Peri-Implantitis and Peri-Mucositis among Private Dental Practitioners in Hyderabad-A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2020, 24, 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.-D.; Tsai, Y.-W.C.; Cheng, W.-C.; Lin, F.-G.; Weng, P.-W.; Chen, Y.-W.; Huang, R.-Y.; Chen, W.-L.; Shieh, Y.-S.; Sung, C.-E. The Referral Pattern and Treatment Modality for Peri-Implant Disease between Periodontists and Non-Periodontist Dentists. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madi, M.; Tabassum, A.; Attia, D.; Al Muhaish, L.; Al Mutiri, H.; Alshehri, T.; Zakaria, O.; Aljandan, B. Knowledge and Attitude of Dental Students Regarding Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Peri-implantitis. J. Dent. Educ. 2024, 88, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Grusovin, M.G.; Worthington, H.V. Treatment of Peri-Implantitis: What Interventions Are Effective? A Cochrane Systematic Review. Eur. J. Oral Implant. 2012, 5, S21–S41. [Google Scholar]

- Jan van Winkelhoff, A. Antibiotics in the Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. Eur. J. Oral Implant. 2012, 5, S43. [Google Scholar]

- Heitz-Mayfield, L.J.A.; Mombelli, A. The Therapy of Peri-Implantitis: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2014, 29, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, K.; Gurzawska-Comis, K.; Klinge, B.; Lund, B.; Brunello, G. Patterns of Antibiotic Prescription in Implant Dentistry and Antibiotic Resistance Awareness among European Dentists: A Questionnaire-based Study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rams, T.E.; Slots, J. Antimicrobial Chemotherapy for Recalcitrant Severe Human Periodontitis. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slots, J. Update on Human Cytomegalovirus in Destructive Periodontal Disease. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2004, 19, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFall, R. Antimicrobial Resistance: Where Are We Now? Br. Stud. Dr. J. 2021, 5, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.R.; Gufran, K.; Alqahtani, A.M.; Alazemi, F.N.; Alzahrani, K.M. Evaluating the Knowledge of General Dentist Towards the Management of Peri-Implant Diseases: A Multi-Center, Cross-Sectional Study. Open Dent. J. 2021, 15, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-T.; Huang, Y.-W.; Zhu, L.; Weltman, R. Prevalences of Peri-Implantitis and Peri-Implant Mucositis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. 2017, 62, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obreja, K.; Ramanauskaite, A.; Begic, A.; Galarraga-Vinueza, M.E.; Parvini, P.; Sader, R.; Schwarz, F. The Prevalence of Peri-implant Diseases around Subcrestally Placed Implants: A Cross-sectional Study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2021, 32, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlGhamdi, J.; Shafik, S.; Al-Mashat, H. Prevalence of Peri-Implant Diseases among Patients Received Dental Implants at Riyadh City, KSA. IJAR 2017, 3, 792–797. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, S.D.; Silva, G.L.M.; Cortelli, J.R.; Costa, J.E.; Costa, F.O. Prevalence and Risk Variables for Peri-implant Disease in Brazilian Subjects. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2006, 33, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos-Jansåker, A.; Lindahl, C.; Renvert, H.; Renvert, S. Nine-to Fourteen-year Follow-up of Implant Treatment. Part II: Presence of Peri-implant Lesions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2006, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinidis, I.K.; Kotsakis, G.A.; Gerdes, S.; Walter, M.H. Cross-Sectional Study on the Prevalence and Risk Indicators of Peri-Implant Diseases. Eur. J. Oral Implant. 2015, 8, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Heitz-Mayfield, L.J.A.; Salvi, G.E. Peri-implant Mucositis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S237–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Sharma, D. Management of Peri-Implant Diseases: A Survey of Australian Periodontists. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymeri, A.; Loos, B.G.; Aronovich, S.; Steigmann, L.; Inglehart, M.R. Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Peri-implantitis: A Cross-cultural Comparison of US and European Periodontists’ Considerations. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaby, M.; Karring, E.; Schou, S.; Isidor, F. Factors Influencing Severity of Peri-implantitis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2016, 27, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, E.; Finkelman, M.; Hanley, J.; Parashis, A.O. Prevalence, Etiology and Treatment of Peri-implant Mucositis and Peri-implantitis: A Survey of Periodontists in the United States. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidlin, P.R.; Sahrmann, P.; Ramel, C.; Imfeld, T.; Müller, J.; Roos, M.; Jung, R.E. Peri-Implantitis Prevalence and Treatment in Implant-Oriented Private Practices: A Cross-Sectional Postal and Internet Survey. Schweiz. Monatsschrift Für Zahnmed. 2012, 122, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini, M.M.; Del Bel Cury, A.A.; Pizzoloto, L.; Acapa, I.R.H.; Shibli, J.A.; Bordin, D. Does Traumatic Occlusal Forces Lead to Peri-Implant Bone Loss? A Systematic Review. Braz. Oral Res. 2019, 33, e069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitz-Mayfield, L.J.; Schmid, B.; Weigel, C.; Gerber, S.; Bosshardt, D.D.; Jönsson, J.; Lang, N.P.; Jönsson, J. Does Excessive Occlusal Load Affect Osseointegration? An Experimental Study in the Dog. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2004, 15, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, C.V.; Harrel, S.K.; Rossmann, J.A.; Kerns, D.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Kontogiorgos, E.D.; Al-Hashimi, I.; Abraham, C. The Role of Occlusion in the Dental Implant and Peri-Implant Condition: A Review. Open Dent. J. 2016, 10, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, D.; Gallucci, G.; Lin, W.; Pjetursson, B.; Polido, W.; Roehling, S.; Sailer, I.; Aghaloo, T.; Albera, H.; Bohner, L. Group 2 ITI Consensus Report: Prosthodontics and Implant Dentistry. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 29, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsch, M.; Walther, W.; Marten, S.-M.; Obst, U. Microbial Analysis of Biofilms on Cement Surfaces: An Investigation in Cement-Associated Peri-Implantitis. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2014, 12, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsch, M.; Obst, U.; Walther, W. Cement-associated Peri-implantitis: A Retrospective Clinical Observational Study of Fixed Implant-supported Restorations Using a Methacrylate Cement. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2014, 25, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, R.L. Influence of Prosthetic and Surgical Parameters on Peri-Implant Marginal Bone Loss. Master’s Thesis, Tufts University, School of Dental Medicine, Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, Y.; Li, Q.; Tang, Z. Prosthetic Emergence Angle in Different Implant Sites and Their Correlation with Marginal Bone Loss: A Retrospective Study. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 18, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Koo, K.; Schwarz, F.; Ben Amara, H.; Heo, S. Association of Prosthetic Features and Peri-implantitis: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Lu, Y.; Fan, Z. Comparing the Clinical Outcome of Peri-Implant Hard and Soft Tissue Treated with Immediate Individualized CAD/CAM Healing Abutments and Conventional Healing Abutments for Single-Tooth Implants in Esthetic Areas Over 12 Months: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2021, 36, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.G., Jr. The Positive Relationship between Excess Cement and Peri-implant Disease: A Prospective Clinical Endoscopic Study. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 1388–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katafuchi, M.; Weinstein, B.F.; Leroux, B.G.; Chen, Y.; Daubert, D.M. Restoration Contour Is a Risk Indicator for Peri-implantitis: A Cross-sectional Radiographic Analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittneben, J.; Joda, T.; Weber, H.; Brägger, U. Screw Retained vs. Cement Retained Implant-supported Fixed Dental Prosthesis. Periodontol. 2000 2017, 73, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, A.A.; Tawse-Smith, A.; Broadbent, J.M.; Leichter, J.W. Peri-Implantitis Diagnosis and Treatment by New Zealand Periodontists and Oral Maxillofacial Surgeons. N. Z. Dent. J. 2014, 110, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garaicoa-Pazmino, C.; Sinjab, K.; Wang, H.-L. Current Protocols for the Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2019, 6, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renvert, S.; Hirooka, H.; Polyzois, I.; Kelekis-Cholakis, A.; Wang, H.-L.; Working Group 3. Diagnosis and Non-Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implant Diseases and Maintenance Care of Patients with Dental Implants—Consensus Report of Working Group 3. Int. Dent. J. 2019, 69, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, G.R.; Samuelsson, E.; Lindahl, C.; Renvert, S. Mechanical Non-Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implantitis: A Single-Blinded Randomized Longitudinal Clinical Study. II. Microbiological Results. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 37, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, K.M.; Fernandes-Costa, A.N.; Silva-Neto, R.D.; Calderon, P.S.; Gurgel, B.C.V. Efficacy of 0.12% Chlorhexidine Gluconate for Non-Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implant Mucositis. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.; Di Spirito, F.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Boccia, G.; Moccia, G.; De Caro, F. Probiotics in Periodontal and Peri-Implant Health Management: Biofilm Control, Dysbiosis Reversal, and Host Modulation. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibli, J.A.; Ferrari, D.S.; Siroma, R.S.; de Figueiredo, L.C.; de Faveri, M.; Feres, M. Microbiological and Clinical Effects of Adjunctive Systemic Metronidazole and Amoxicillin in the Non-Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implantitis: 1 Year Follow-Up. Braz. Oral Res. 2019, 33, e080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.P.; Rosen, P.S.; Chambrone, L.; Greenwell, H.; Kao, R.T.; Klokkevold, P.R.; McAllister, B.S.; Reynolds, M.A.; Romanos, G.E.; Wang, H.-L. American Academy of Periodontology Best Evidence Consensus Statement on the Efficacy of Laser Therapy Used Alone or as an Adjunct to Non-Surgical and Surgical Treatment of Periodontitis and Peri-Implant Diseases. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglundh, T.; Wennström, J.L.; Lindhe, J. Long-Term Outcome of Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. A 2-11-Year Retrospective Study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 29, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.K.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, C. Surgical Therapy of Peri-Implantitis with Local Minocycline: A 6-Month Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bispo Júnior, J.P. Social Desirability Bias in Qualitative Health Research. Rev. Saude Publica 2022, 56, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Frequency n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Males | 160 (52.8) |

| Females | 143 (47.2) | |

| Highest degree attained | Bachelor’s degree | 246 (81.2) |

| Master’s degree | 26 (8.6) | |

| Fellowship | 14 (4.6) | |

| Ph.D. | 17 (5.6) | |

| Work sector | Dental college | 111 (36.6) |

| Private sector | 105 (34.7) | |

| Governmental sector | 87 (28.7) | |

| Perform or assist in implant surgery on a regular basis | Yes | 105 (34.7) |

| No | 198 (65.3) | |

| Received formal education/training on implant therapy | Yes | 171 (56.4) |

| No | 132 (43.6) | |

| Attended lecture on diagnosis/treatment of peri-implantitis | Yes | 127 (41.9) |

| No | 176 (58.1) | |

| Relative Use n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | ||

| What signs and symptoms help diagnose peri-implantitis? | Bleeding/suppuration upon gentle probing with a blunt instrument | 164 (54.1) | 85 (28.1) | 37 (12.2) | 11 (3.6) | 6 (2.0) |

| Marginal tissue swollen and red | 135 (45.6) | 92 (30.4) | 58 (18.1) | 7 (2.3) | 11 (3.6) | |

| Periodontal probe can be advanced ≥5 mm into the sulcus | 152 (50.2) | 97 (32.0) | 37 (12.2) | 9 (3.0) | 8 (2.6) | |

| Pain | 118 (38.9) | 98 (32.3) | 64 (21.2) | 13 (4.3) | 10 (3.3) | |

| Crater-like bone defect around implant | 164 (54.1) | 94 (31.0) | 33 (10.9) | 3 (1.0) | 9 (3.0) | |

| Radiographs you perform after implant placement | Panoramic radiograph | 118 (38.9) | 51 (16.8) | 70 (23.2) | 34 (11.2) | 30 (9.9) |

| Peri-apical X-ray | 224 (73.9) | 26 (8.6) | 38 (12.5) | 9 (3.0) | 6 (2.0) | |

| CBCT | 88 (29.0) | 48 (15.8) | 99 (32.7) | 42 (13.9) | 26 (8.6) | |

| When do you perform the baseline X-ray after implant placement? | Immediately after surgery | 230 (75.9) | 28 (9.2) | 29 (9.6) | 3 (1.0) | 13 (4.3) |

| After 1–3 weeks | 81 (26.7) | 73 (24.1) | 73 (24.1) | 34 (11.2) | 42 (13.9) | |

| At implant uncovering | 109 (36.0) | 74 (24.2) | 62 (20.5) | 32 (10.6) | 26 (8.7) | |

| At prostheses delivery | 182 (60.1) | 46 (16.2) | 37 (12.2) | 24 (7.9) | 14 (3.6) | |

| Radiographic representation of peri-implantitis you rely on in your diagnosis | A radio-opaque area at the apical aspect of the implant | 42 (13.9) | 51 (16.8) | 52 (17.2) | 42 (13.8) | 116 (38.3) |

| A radiolucent area at the apical aspect of the implant | 113 (37.3) | 76 (25.1) | 66 (21.8) | 18 (5.9) | 30 (9.9) | |

| Vertical bone loss with saucer-shaped defect | 181 (59.7) | 65 (21.5) | 44 (14.5) | 3 (1.0) | 10 (3.3) | |

| Treatment | Relative Use n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | ||

| What type of instruments/agents do you use for implant debridement? | Titanium curettes | 104 (34.3) | 47 (15.5) | 54 (17.8) | 22 (7.3) | 76 (25.1) |

| Plastic curettes | 142 (46.9) | 71 (23.5) | 51 (16.8) | 8 (2.6) | 31 (10.2) | |

| Stainless steel instrument | 40 (13.2) | 50 (16.5) | 55 (18.1) | 26 (8.6) | 132 (43.6) | |

| Laser | 47 (15.5) | 62 (20.5) | 76 (25.1) | 27 (8.9) | 91 (30.0) | |

| Hydrogen peroxide | 47 (15.5) | 72 (23.8) | 61 (20.1) | 34 (11.2) | 89 (29.4) | |

| Chlorhexidine | 107 (35.3) | 83 (27.4) | 62 (20.5) | 15 (4.9) | 36 (11.9) | |

| Which of the following treatment methods do you use for the treatment of peri-implantitis? | Oral hygiene instructions | 231 (76.2) | 34 (11.2) | 25 (8.3) | 1 (0.3) | 12 (4.0) |

| Antimicrobial gel OR mouthrinse | 157 (51.7) | 75 (24.8) | 53 (17.5) | 2 (0.7) | 16 (5.3) | |

| Non-surgical debridement | 164 (54.1) | 62 (20.5) | 54 (17.8) | 4 (1.3) | 19 (6.3) | |

| Local antibiotics | 85 (28.1) | 73 (24.1) | 75 (24.8) | 32 (10.6) | 32 (12.4) | |

| Surgical debridement | 66 (21.8) | 57 (18.8) | 92 (30.4) | 36 (11.9) | 52 (17.1) | |

| Resective surgery | 44 (14.5) | 48 (15.8) | 82 (27.1) | 51 (16.8) | 78 (25.8) | |

| Regenerative surgery | 51 (16.8) | 58 (19.1) | 79 (26.1) | 44 (14.5) | 71 (23.5) | |

| Control of occlusion | 97 (32.0) | 66 (21.8) | 81 (27.0) | 25 (8.3) | 34 (11.2) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zakaria, O.; Tabassum, A.; Attia, D.; Alshehri, T.; Alanazi, D.A.; Alshehri, J.; Alshehri, S.; Chopra, A.; Madi, M. Dental Practitioners’ Knowledge and Attitudes Toward the Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120387

Zakaria O, Tabassum A, Attia D, Alshehri T, Alanazi DA, Alshehri J, Alshehri S, Chopra A, Madi M. Dental Practitioners’ Knowledge and Attitudes Toward the Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. Dentistry Journal. 2024; 12(12):387. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120387

Chicago/Turabian StyleZakaria, Osama, Afsheen Tabassum, Dina Attia, Turki Alshehri, Danya A. Alanazi, Jana Alshehri, Sami Alshehri, Aditi Chopra, and Marwa Madi. 2024. "Dental Practitioners’ Knowledge and Attitudes Toward the Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Peri-Implantitis" Dentistry Journal 12, no. 12: 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120387

APA StyleZakaria, O., Tabassum, A., Attia, D., Alshehri, T., Alanazi, D. A., Alshehri, J., Alshehri, S., Chopra, A., & Madi, M. (2024). Dental Practitioners’ Knowledge and Attitudes Toward the Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. Dentistry Journal, 12(12), 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120387