Social Inequalities and Geographical Distribution in Caries Treatment Needs among Schoolchildren Living in Buenos Aires City: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Study and Sample Size

2.2. Clinical Assessment and Calibration Procedures

- (a)

- Expository class (2 h) with photographs (n = 36) aimed at the recognition of the categories established in the CTNI and the cut-off points between the different categories and the protocol to carry out the diagnosis.

- (b)

- Caries detection using extracted teeth (n = 30) (ex vivo 2 h). The specimens were examined after drying the surfaces with compressed air and under adequate lighting. Each operator recorded the observed findings according to the lesion and activity criteria for each tooth surface. The results were then discussed with the benchmark examiner.

- (c)

- Clinical practice (20 h), which included the following steps:

- Assignment to each examiner of 6 volunteer children who provided a balanced number of dental surfaces with CTNI codes.

- Observation and recording of the findings in an ad hoc spreadsheet. The visual–tactile clinical examination was performed with a frontal light, WHO probes, magnification (2.5×) and air drying of the surfaces.

- Re-evaluation (one week later) of each patient by the reference examiner and recording of findings.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Selwitz, R.H.; Ismail, A.I.; Pitts, N.B. Dental caries. Lancet 2007, 369, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaj, M.; York, H.W.; Sripada, K.; Besnier, E.; Vonen, H.D.; Aravkin, A.; Friedman, J.; Griswold, M.; Jensen, M.R.; Mohammad, T.; et al. Parental education and inequalities in child mortality: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2021, 398, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, D.L.; Lee, R.S.; Nucci, M.; Grembowski, D.; Jolles, C.Z.; Milgrom, P. Reducing oral health disparities: A focus on social and cultural determinants. BMC Oral Health 2006, 6 (Suppl. S1), S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukovic, A.; Schmutz, K.A.; Borg-Bartolo, R.; Cocco, F.; Rosianu, R.S.; Jorda, R.; Maclennon, A.; Cortes-Martinicorenas, J.F.; Rahiotis, C.; Madléna, M.; et al. Caries status in 12-year-old children, geographical location and socioeconomic conditions across European countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2024; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oude Groeniger, J.; Houweling, T.A.; Jansen, P.W.; Horoz, N.; Buil, J.M.; van Lier, P.A.; van Lenthe, F.J. Social inequalities in child development: The role of differential exposure and susceptibility to stressful family conditions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2023, 77, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-López, S.; Armenta, K.; Eckert, G.; Maupomé, G. Cross-Sectional Association between Behaviors Related to Sugar-Containing Foods and Dental Outcomes among Hispanic Immigrants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, B.; Fernandez-Sanchez, H.; Fouche, C.; Evans, C.; Sibeko, L.; Tulli, M.; Bulaong, A.; Kwankye, S.O.; Ani-Amponsah, M.; Okeke-Ihejirika, P.; et al. Scoping Review of the Health of African Immigrant and Refugee Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozos-Guillén, A.; Molina, G.; Soviero, V.; Arthur, R.A.; Chavarria-Bolaños, D.; Acevedo, A.M. Management of dental caries lesions in Latin American and Caribbean countries. Braz. Oral Res. 2021, 35 (Suppl. S1), e055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas 2022: Indicadores Demográficos, por Sexo y Edad” (PDF). INDEC. Available online: https://censo.gob.ar (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Argentina National of Office of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Censos (INDEC). 2023. Available online: https://www.indec.gob.ar/uploads/informesdeprensa/eph_pobreza_03_2442F61D046F.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Silva da Cruz, A.J.; Moreno-Drada, J.A.; Santos, J.S.; de Abreu, M.H.N.G. Dental Caries Remains a Significant Public Health Problem for South American Indigenous People. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2020, 20, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C.N.; Borjas, M.I.; Cambría-Ronda, S.D.; Zavala, W. Prevalence and severity of early childhood caries in malnourished children in Mendoza, Argentina. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 2020, 33, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C.N.; Squassi, A.F.; Bordoni, N. Dental status and dental treatment demands in preschoolers from urban and underprivileged urban areas in Mendoza City, Argentina. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 2015, 28, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fort, A.; Fuks, A.J.; Napoli, A.V.; Palomba, S.; Pazos, X.; Salgado, P.; Klemonskis, G.; Squassi, A. Distribución de caries dental y asociación con variables de protección social en niños de 12 años del partido de Avellaneda, provincia de Buenos Aires. Salud Colect. 2017, 13, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitts, N.B.; Twetman, S.; Fisher, J.; Marsh, P.D. Understanding dental caries as a non-communicable disease. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 231, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstrand, K.R.; Gimenez, T.; Ferreira, F.R.; Mendes, F.M.; Braga, M.M. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System—ICDAS: A Systematic Review. Caries Res. 2018, 52, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argentine Ministry of Education. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/capital-humano/educacion (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Argentine Annual House Household Surveys. Available online: https://www.olasdata.org/en/argentina/ (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Sorazabal, A.L.; Salgado, P.; Ferrarini, S.; Lazzati, R.; Squassi, A.F.; Campus, G.; Klemonskis, G. An Alternative Technique for Topical Application of Acidulated Phosphate Fluoride (APF) Gel: A Two-Years Double-Blind Randomization Clinical Trial (RCT). Medicina 2023, 59, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu, G.; Arman, F. k-Means clustering by using the calculated Z-scores from QEEG data of children with dyslexia. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2023, 12, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijster, D.; Sheiham, A.; Hobdell, M.H.; Itchon, G.; Monse, B. Associations between oral health-related impacts and rate of weight gain after extraction of pulpally involved teeth in underweight preschool Filipino children. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeminia, M.; Abdi, A.; Shohaimi, S.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Salari, N.; Mohammadi, M. Dental caries in primary and permanent teeth in children’s worldwide, 1995 to 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Face Med. 2020, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, Y.O.; Luo, Y.L.; Duangthip, D.; El Tantawi, M.; Benzian, H.; Schroth, R.J.; Feldens, C.A.; Virtanen, J.I.; Al-Batayneh, O.B.; Diaz, A.C.M.; et al. Early Childhood Caries Advocacy Group (ECCAG). A scoping review of the links between early childhood caries and clean water and sanitation: The Sustainable Development Goal 6. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfim, R.A.; Della Bona, A.; Cury, J.A.; Celeste, R.K. Brazilian primary dental care in a universal health system: Challenges for training and practice. J. Dent. 2024, 144, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modha, B. Promoting Access to Dental Care in a Developing Caribbean Nation, Post-disaster. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2023, 34, 1136–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CODE | Clinical Situation | Unit of Analysis | Treatment Plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | Sound teeth with history of preventive measures | Mouth | Preventive program: low or moderate caries risk |

| 01 | Sound teeth without history of preventive measures | Preventive program: low or moderate caries risk | |

| 02 | Presence of initial caries lesions | Preventive program: high caries risk | |

| 03 | Presence of cavitated lesions affecting enamel and/or dentine | 1 quadrant | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment |

| 04 | 2 quadrants | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment | |

| 05 | 3 quadrants | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment | |

| 06 | 4 quadrants | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment | |

| 07 | Presence of cavitated lesions affecting enamel and/or dentine with pulp involvement | 1 quadrant | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment + pulp treatment |

| 08 | 2 quadrants | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment + pulp treatment | |

| 09 | 3 quadrants | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment + pulp treatment | |

| 10 | 4 quadrants | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment + pulp treatment | |

| 11 | Presence of extensive cavitated lesions without possibilities of restorative treatment or presence of abscess or fistula | 1 quadrant | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment + surgical treatment and eventual rehabilitation |

| 12 | 2 quadrants | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment + surgical treatment and eventual rehabilitation | |

| 13 | 3 quadrants | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment + surgical treatment and eventual rehabilitation | |

| 14 | 4 quadrants | Preventive program: high caries risk + restorative treatment + surgical treatment and eventual rehabilitation |

| Caries Prevalence | Severe Caries Prevalence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTNI Score (0–2) n (%) | CTNI Score (3–14) n (%) | CTNI Score (0–7) n (%) | CTNI Score (8–14) n (%) | ||

| Sex | Males | 7366 (52.46) | 15,321 (51.88) | 16,211 (51.88) | 6476 (52.54) |

| Females | 6674 (47.54) | 14,210 (48.12) | 15,035 (48.12) | 5849 (47.46) | |

| Pearson χ2(2) = 1.30 p = 0.26 | Pearson χ2(2) = 1.55 p = 0.21 | ||||

| Year | 2016 | 5655 (40.28) | 11,688 (39.58) | 12,626 (40.41) | 4717 (38.27) |

| 2017 | 4008 (28.55) | 8417 (28.50) | 8856 (28.34) | 3569 (28.96) | |

| 2018 | 4377 (31.18) | 9426 (31.92) | 9764 (31.25) | 4039 (32.77) | |

| Pearson χ2(2) = 2.83 p = 0.24 | Pearson χ2(2) = 17.77 p < 0.01 | ||||

| Living Area | CABA 1 | 4125 (29.38) | 13,487 (45.67) | 11,106 (35.54) | 6506 (52.79) |

| CABA 2 | 7830 (55.77) | 13.467 (45.60) | 16,239 (51.97) | 5058 (41.04) | |

| CABA 3 | 2085 (14.85) | 2577 (8.73) | 3901 (12.48) | 761 (6.17) | |

| Pearson χ2(2) = 1.2 × 103 p < 0.01 | Pearson χ2(2) = 1.2 × 103 p < 0.01 | ||||

| Health | Public | 4775 (34.07) | 17,819 (60.47) | 13,937 (44.70) | 8657 (70.35) |

| Private/social security | 9150 (65.28) | 11,386 (38.64) | 17,011 (54.56) | 3525 (28.65) | |

| No replies | 92 (0.66) | 263 (0.89) | 232 (0.74) | 123 (1.00) | |

| Pearson χ2(2) = 2.7 × 103 p < 0.01 | Pearson χ2(2) = 2.4 × 103 p < 0.01 | ||||

| Municipality | Infant Mortality Rate | % Employment of the Head of the Household | % Households with Precarious Tenure | % Public System Only | % Attend Public Education | % Completed Primary School | % Unemployed | Z Score (IPCF) | % Overcrowding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.0 | 74.3 | 16.3 | 30.2 | 70.1 | 14.6 | 8.7 | 0.04 | 20.6 |

| 2 | 3.9 | 67.4 | 12.0 | 6.8 | 46.8 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 1.43 | 4.7 |

| 3 | 6.7 | 72.3 | 9.4 | 19.3 | 58.3 | 12.9 | 7.5 | −0.21 | 13.6 |

| 4 | 8.8 | 65.4 | 23.0 | 36.8 | 75.0 | 24.3 | 12.7 | −1.14 | 19.7 |

| 5 | 6.6 | 69.9 | 9.1 | 11.6 | 56.6 | 8.2 | 6.2 | 0.31 | 7.6 |

| 6 | 5.0 | 72.3 | 9.0 | 7.7 | 50.8 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 0.64 | 3.2 |

| 7 | 6.8 | 71.2 | 12.9 | 24.7 | 61.0 | 13.2 | 8.6 | −0.57 | 12.3 |

| 8 | 8.7 | 67.1 | 26.3 | 46.4 | 74.2 | 29.1 | 13.7 | −1.78 | 22.9 |

| 9 | 8.4 | 67.1 | 12.2 | 25.4 | 57.9 | 19.6 | 8.0 | −1.07 | 11.2 |

| 10 | 4.9 | 69.0 | 8.9 | 17.9 | 55.0 | 11.9 | 6.9 | −0.62 | 6.4 |

| 11 | 6.3 | 69.8 | 7.8 | 13.5 | 52.4 | 10.3 | 8.2 | −0.22 | 7.2 |

| 12 | 6.1 | 70.8 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 51.9 | 10.3 | 7.2 | 0.17 | 5.8 |

| 13 | 4.8 | 71.0 | 9.6 | 6.1 | 41.1 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 1.21 | 3.6 |

| 14 | 4.1 | 72.5 | 10.4 | 5.6 | 38.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.82 | 3.7 |

| 15 | 6.9 | 6.91 | 71.2 | 12.9 | 59.8 | 11.4 | 7.4 | 0.00 | 6.7 |

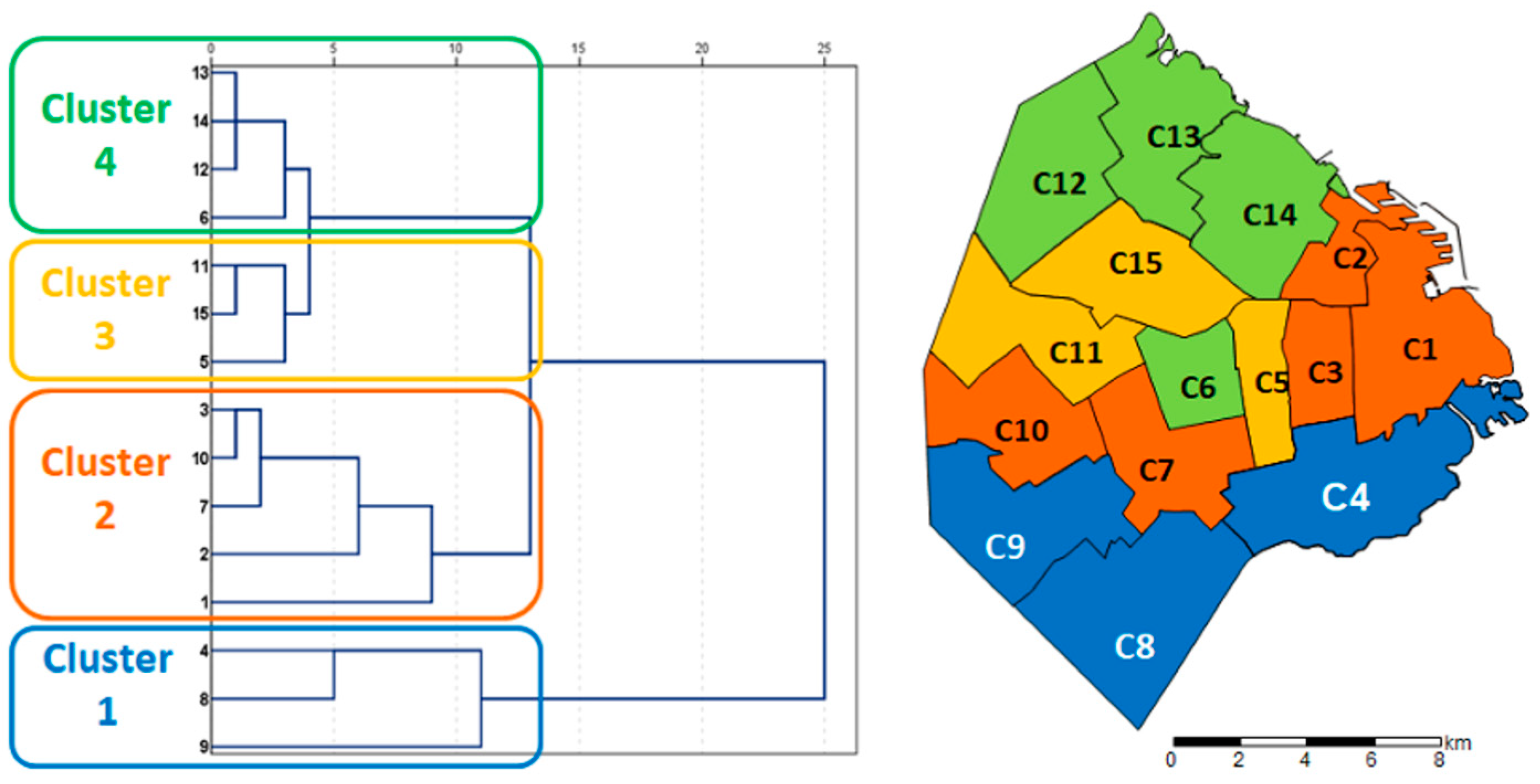

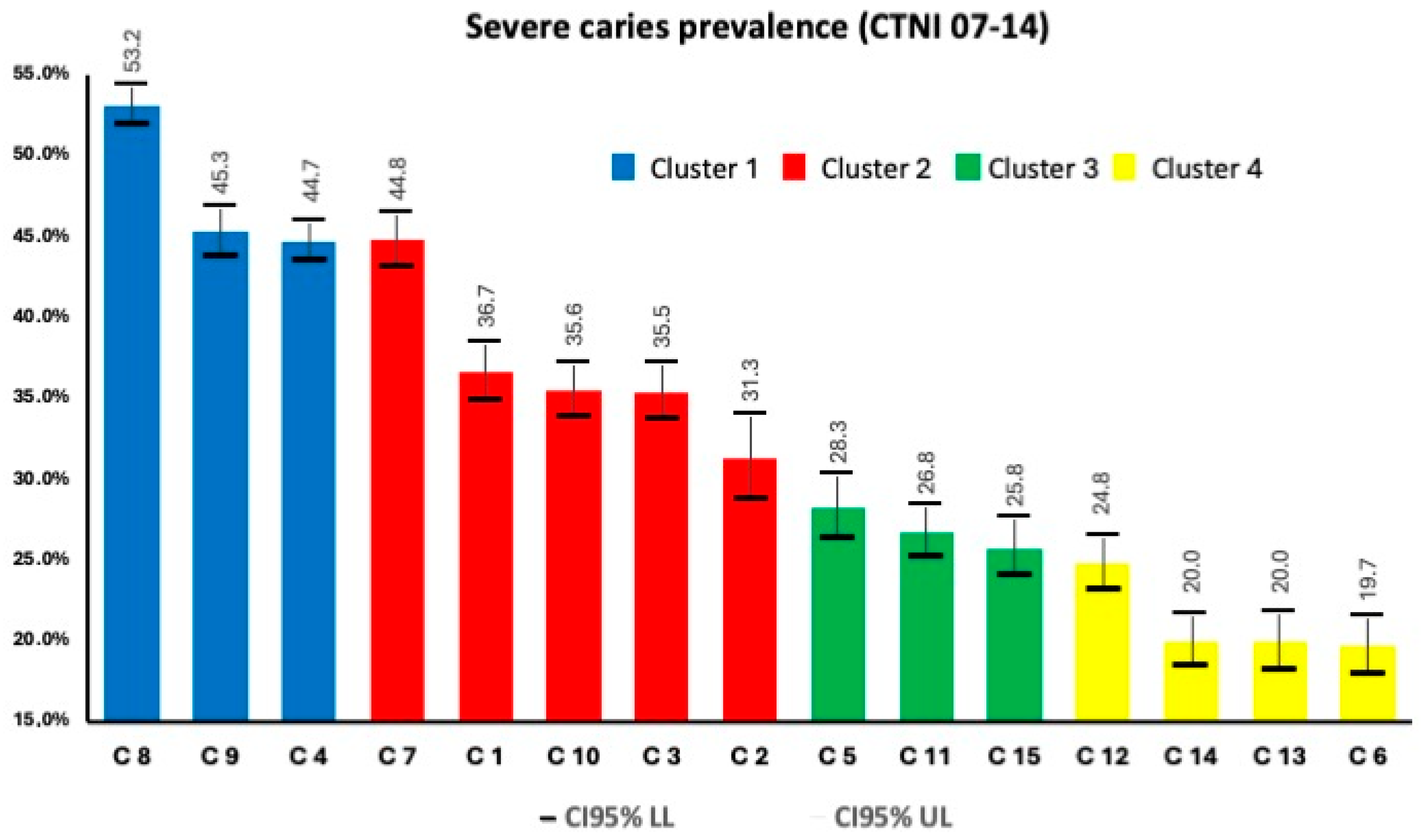

| Clusters * | % Employment of the Head of the Household | % Households with Precarious Tenure | % Public Education (3 years or more) | % Public Health System Only | % Completed Primary School | % Unemployed | Z Score (IPCF) | % Overcrowding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | 65.8 | 20.5 | 69.0 | 36.2 | 24.3 | 11.4 | −1.330 | 17.9 |

| Cluster 2 | 70.3 | 10.3 | 56.3 | 12.6 | 10.0 | 7.3 | 0.030 | 7.1 |

| Cluster 3 | 70.8 | 11.9 | 58.3 | 19.8 | 11.6 | 7.5 | 0.013 | 11.5 |

| Cluster 4 | 71.7 | 9.7 | 45.5 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 0.958 | 4.1 |

| Buenos Aires | 69.9 | 12.7 | 56.6 | 18.4 | 12.5 | 7.8 | 0.00 | 9.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ventura, F.; Lazzati, M.R.; Salgado, P.A.; Rossi, G.N.; Wolf, T.G.; Squassi, A.; Campus, G. Social Inequalities and Geographical Distribution in Caries Treatment Needs among Schoolchildren Living in Buenos Aires City: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12100325

Ventura F, Lazzati MR, Salgado PA, Rossi GN, Wolf TG, Squassi A, Campus G. Social Inequalities and Geographical Distribution in Caries Treatment Needs among Schoolchildren Living in Buenos Aires City: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dentistry Journal. 2024; 12(10):325. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12100325

Chicago/Turabian StyleVentura, Fiorella, Maria Rocio Lazzati, Pablo Andres Salgado, Glenda Natalia Rossi, Thomas G. Wolf, Aldo Squassi, and Guglielmo Campus. 2024. "Social Inequalities and Geographical Distribution in Caries Treatment Needs among Schoolchildren Living in Buenos Aires City: A Cross-Sectional Study" Dentistry Journal 12, no. 10: 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12100325

APA StyleVentura, F., Lazzati, M. R., Salgado, P. A., Rossi, G. N., Wolf, T. G., Squassi, A., & Campus, G. (2024). Social Inequalities and Geographical Distribution in Caries Treatment Needs among Schoolchildren Living in Buenos Aires City: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dentistry Journal, 12(10), 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12100325