Classifying Children’s Behaviour at the Dentist—What about ‘Burnout’?

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

2. Recognition and Identification

2.1. The Dental Burnout Concept

2.2. Signs and Symptoms of Dental Burnout

- Loss of care and motivation—the child may no longer present with the same enthusiasm as previous treatment appointments; they may become less communicative, including blunt or one-word replies, and no longer maintain eye-contact;

- Avoidance behaviours—the child who previously attended treatment without concern may attempt to avoid it completely by, e.g., refusing to come in from the car or waiting room, or may refuse to come at all and want to stay at home/school;

- Worry, anxiety and fear—the previously calm and composed child may be experiencing an increase in fear, worry or anxiety, particularly if they are approaching more invasive aspects of treatment such as exodontia—when these feelings outweigh a child’s ability to cope it may result in tears, feeling sick (including stomach aches and headaches), shaking, sweating and freezing;

- Attitude shift and emotional changes—the child’s attitude may shift from being positive, open and honest to a predominantly negative mindset—they may be less tolerant to minor setbacks such as being kept waiting a few minutes past their anticipated appointment time or recurrent loss of orthodontic separators prior to preformed metal crown (PMC) placement;

- Concentration—the child may become easily frustrated with situations or aspects they did not previously get triggered by, such as lost fillings or administration of local anaesthetic; in addition, they may find it hard to keep concentration and exhibit annoyance when required to sit for longer appointments such as during root canal treatment.

2.3. Likely Candidates for Dental Burnout

- Limited dental experience—if a child’s only dental experiences have involved check-ups or basic operative care (typically without local anaesthetic), their lack of ‘dental sophistication’ can result in limited treatment stamina and an inability to cope with longer and, on occasion, uncomfortable appointments further along a complex treatment plan [25];

- Dental trauma—in addition to the initial physical trauma itself, e.g., tooth avulsion, the experience of immediate and short-term management is often painful and frightening for a child and can significantly impact them on an emotional and psychological level; significant long-term monitoring is necessary, particularly in patients with a developing dentition, alongside knowledge of risks such as loss of vitality and the need for more invasive treatment such as root canal therapy [50];

- Medical trauma—medical trauma may occur in children as a response to single or multiple medical events; it refers to the psychological (and sometimes physiological) response of a child to pain, injury, serious illness, medical procedures and invasive or frightening treatment experiences in the medical setting, such as those involved with childhood cancer—young children are still developing their cognitive skills and process information differently, hence they may associate dental pain with punishment and believe they did something wrong. This could lead to burnout during invasive dental treatment, despite previous successful appointments [51];

- Developmental dental defects (DDD)—developmental defects of the enamel and dentine are lifelong conditions that require multidisciplinary input as well as short-term and long-term management that can be increasingly challenging in young children. Pain, sensitivity and aesthetic concerns are commonplace, alongside a reduced strength and integrity of the bond of enamel to composite that often results in failed restorations. Molar Incisor Hypomineralisation (MIH), for example, with a global prevalence of 14.2%, has a significant impact on both patients and dentists and has been shown to negatively impact a patient’s oral-health-related quality of life (OHRQoL)—a recent systematic review by Jälevik et al. [52] found that already-restored MIH molars remain within short re-treatment cycles; sensitivity becomes problematic when it hinders the possibility of obtaining sufficient pain control; and, consequently, behavioural management problems arise due to dental fear and anxiety related to the pain experienced by patients during multiple treatment appointments. In addition, the burden of other chronic developmental conditions such as amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) or dentinogenesis imperfecta (DI) may also be associated with significant medical co-morbidities, further increasing the risk of burnout due to possible previous medical trauma [53];

- Dental fear and anxiety (DFA)—DFA is common in CYP, with an estimated prevalence between 6% and 20% in those aged 4–18 years old [48]. Potentially cooperative children, especially those who exhibit ‘timid’ and/or ‘tense-cooperative’ behaviour, are at increased risk of burnout, should they be exposed to invasive and uncomfortable procedures without adequate preparation and coping strategies;

- Re-treatment—children who require extensive re-treatment because of failed or failing treatment are increasingly susceptible to burnout. This includes changes as a result of failed complex treatment or further trauma, as well as recurrently debonding restorations such as those associated with AI. Patients requiring re-treatment may be close to burnout already, due to ongoing frustrations with previous protracted treatment in addition to unanticipated problems which require subsequent further treatment;

- Personal circumstances—children who undergo a significant change in circumstances during a long treatment plan are also at risk of burnout. These are usually external to the dental setting and may be due to finding transitions into school extremely stressful, continuous exposure to stressful or traumatic events, struggling with external changes or being extremely driven to excel at school exams [47,54].

3. Minimising and Managing Dental Burnout

3.1. History Taking

“…his behavior [sic] was at times totally dysregulated. While taking a health and medical history, they learned that the child, David, had endured many painful, frightening, and invasive medical procedures beginning at 21 months of age…”

3.2. Communication

3.3. Emotional Exchanges

3.4. Continuity of Care

3.5. Cooperation vs. Compliance

3.6. Behaviour Management Spectrum

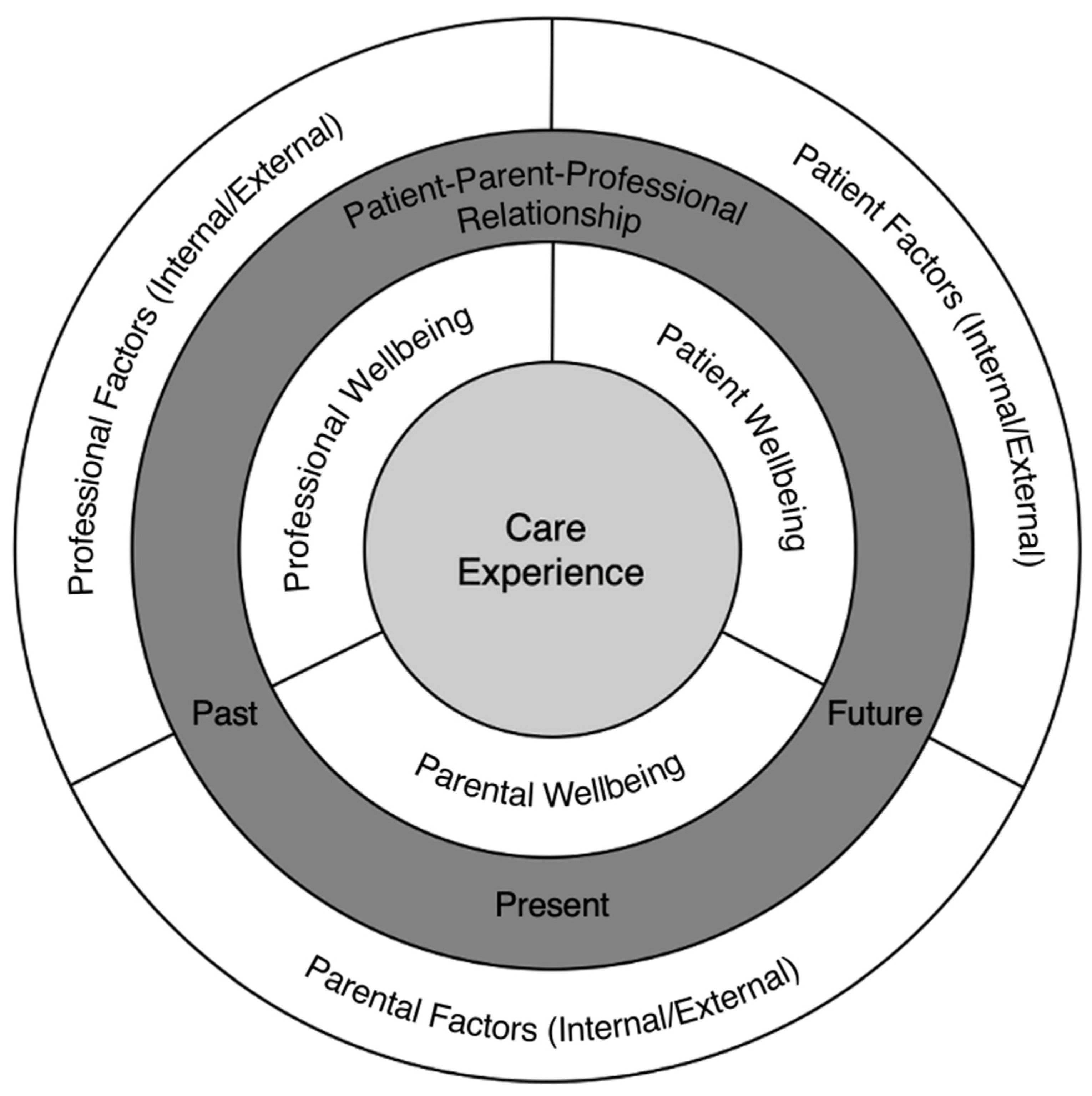

4. The Burnout Triad

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

References

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced Burn-Out. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, H. Burnout: The High Cost of High Achievement; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Burn-Out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Collin, V.; Toon, M.; O’Selmo, E.; Reynolds, L.; Whitehead, P. A survey of stress, burnout and well-being in, U.K. dentists. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorter, R.C. Work stress and burnout among dental hygienists. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2005, 3, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Hasan, O.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; West, C.P. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General, U.S. Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, K.; Mehrabadi, V.A.; Baghi, V.; Rezaei, H.; Gheshlagh, R.G. Prevalence of occupational stress among Iranian physicians and dentist: A systematic and meta-analysis study. Przegl. Epidemiol. 2022, 76, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Polo, C.; Casado, A.M.M.; Montero, J. Burnout syndrome in dentists: Work-related factors. J. Dent. 2022, 121, 104143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evaristo-Chiyong, T.; Mattos-Vela, M.A.; Agudelo-Suárez, A.A.; Armas-Vega, A.d.C.; Cuevas-González, J.C.; Díaz-Reissner, C.V.; López Torres, A.C.; Martínez-Delgado, C.M.; Paz-Betanco, M.A.; Pérez-Flores, M.A.; et al. General Labor Well-Being in Latin American Dentists during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Knight, A. Questionnaire Survey of Burnout Amongst Dentists in Singapore. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.T.; Allen, C.D.; Coates, J.; Turner, A.; Prior, J. How to reduce the stress of general dental practice: The need for research into the effectiveness of multifaceted interventions. Br. Dent. J. 2006, 200, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessas, A.; Paisi, M.; Bryce, M.; Burns, L.; O’Brien, T.; Hanoch, Y.; Witton, R. Mental health and wellbeing interventions in the dental sector: A systematic review [published online ahead of print, 7 December 2022]. Evid. Based Dent. 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basson, R.A. Management and Prevention of Burnout in the Dental Practitioner. Dentistry 2013, 3, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, G.; Salyers, M.P.; Rollins, A.L.; Monroe-DeVita, M.; Pfahler, C. Burnout in mental health services: A review of the problem and its remediation. Adm. Policy Ment. Health. 2012, 39, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R. Trusting the Dentist—Expecting a Leap of Faith vs. a Well-Defined Strategy for Anxious Patients. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uziel, N.; Meyerson, J.; Giryes, R.; Eli, I. Empathy in dental care—The role of vicarious trauma. Int. Dent. J. 2019, 69, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, D.A. Countering compassion fatigue: A requisite nursing agenda. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2011, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocker, F.; Joss, N. Compassion Fatigue among Healthcare, Emergency and Community Service Workers: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, W.; Talbot, S.; Dean, A. Reframing Clinician Distress: Moral Injury Not Burnout. Fed. Pract. 2019, 36, 400–402. [Google Scholar]

- RDH. What is Moral Injury, and Is It Affecting Hygienists? Online. 2020. Available online: https://www.rdhmag.com/career-profession/personal-wellness/article/14169226/what-is-moral-injury-and-is-it-affecting-dental-hygienists (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- NHS Leadership Academy. Trauma and Moral Injury. Online. 2020. Available online: https://people.nhs.uk/guides/conversations-about-painful-subjects/steps/trauma-and-moral-injury/ (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Čartolovni, A.; Stolt, M.; Scott, P.A.; Suhonen, R. Moral injury in healthcare professionals: A scoping review and discussion. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Aulak, D.S.; Mangat, S.S.; Aulak, M.S. Systematic review: Factors contributing to Burn-Out in dentistry. Occup. Med. 2016, 66, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Moro, J.; Soares, J.P.; Massignan, C.; Oliveira, L.B.; Ribeiro, D.M.; Cardoso, M.; de Luca Canto, G.; Bolan, M. Burnout syndrome among dentists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Evid.-Based Dent. Pr. 2022, 22, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, C.; Jerome, L. Patient and dentist burnout − a two-way relationship. Dent. Update 2018, 45, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, J.W. Patient burnout, and other reasons for noncompliance. Diabetes Educ. 1983, 9, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dental Protection. Breaking the Burnout Cycle. Keeping Dentists and Patients Safe. 2019. Available online: https://www.dentalprotection.org/docs/librariesprovider4/dpl-publications/ireland/1907310561-ire-dp-burnout-policy-paper.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Lin, S.H.; Huang, Y.C. Life stress and academic burnout. Act. Learn. High Educ. 2014, 15, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito-López, J.; Chacón-Cuberos, R.; Romero-Díaz de la Guardia, J.J.; Parejo-Jiménez, N.; Rodríguez-Fernández, S.; Estrada-Vidal, L.I. Prevention of Children’s Burnout at School through the Tutoring and Guidance Process. A Structural Equation Model Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walburg, V. Burnout among high school students: A literature review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 42, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Wang, F.; Wang, W.; Li, Y. Parents’ education anxiety and children’s academic burnout: The role of parental burnout and family function. Front. Psychol. 2022, 4, 6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Georganta, K. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (BSPD; Royal College of Surgeons of England. Non-Pharmacological Behaviour Management (Revised). 2011. Available online: https://www.bspd.co.uk/Portals/0/Public/Files/Guidelines/Non-pharmacological%20behaviour%20management%20.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Wright, G.Z.; Kupietzky, A. (Eds.) Wright’s Behavior Management in Dentistry for Children, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom, P.; Vignehsa, H.; Weinstein, P. Adolescent dental fear and control: Prevalence and theoretical implications. Behav. Res. Ther. 1992, 30, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsarheed, M. Children’s Perception of Their Dentists. Eur. J. Dent. 2011, 5, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K.R. Learned helplessness revisited: Biased evaluation of goals and action potential are major risk factors for emotional disturbance. Cogn. Emot. 2022, 36, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Maier, S.F. Failure to escape traumatic shock. J. Exp. Psychol. 1967, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boddez, Y.; Van Dessel, P.; De Houwer, J. Learned helplessness and its relevance for psychological suffering: A new perspective illustrated with attachment problems, burn-out, and fatigue complaints. Cogn. Emot. 2022, 36, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, D.W.; Allan, J.L.; Powell, D.J.H.; Jones, M.C.; Farquharson, B.; Bell, C.; Johnston, M. Why does work cause fatigue? A real-time investigation of fatigue, and determinants of fatigue in nurses working 12-h shifts. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Muraven, M.; Tice, D.M. Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Tice, D.M.; Vohs, K.D. The Strength Model of Self-Regulation: Conclusions From the Second Decade of Willpower Research. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzlicht, M.; Schmeichel, B.J.; Macrae, C.N. Why self-control seems (but may not be) limited. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.C.; Kofler, L.M.; Forster, D.E.; McCullough, M.E. A series of meta-analytic tests of the depletion effect: Self-control does not seem to rely on a limited resource. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2015, 144, 796–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, A.; Boddez, Y.; De Houwer, J. The power of goal-directed processes in the causation of emotional and other actions. Emot. Rev. 2017, 9, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnell, C.C.; Flavell, T.; Wilson, K.E. LARAGA–Pharmacological behaviour management in paediatric dentistry in the, U.K. Pediatric. Dent. J. 2022, 32, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watter, L. Can Children Experience Burnout? 2022. Available online: https://m1psychology.com/can-children-experience-burnout/ (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Morgan, A.G.; Rodd, H.D.; Porritt, J.M.; Baker, S.R.; Creswell, C.; Newton, T.; Williams, C.; Marshman, Z. Children’s experiences of dental anxiety. Int. J. Paed. Dent. 2016, 27, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Hollingsworth, A.; Hicks, M.; Dobrota, S.; Chu, L.F. The Burnout Dyad: A Collaborative Approach for Including Patients in a Model of Provider Burnout. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2021, 41, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arhakis, A.; Athanasiadou, E.; Vlachou, C. Social and psychological aspects of dental trauma, behavior management of young patients who have suffered dental trauma. Open Dent. J. 2017, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, M.G. Play therapy treatment of pediatric medical trauma: A retrospective case study of a preschool child. Int. J. Play Ther. 2020, 29, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jälevik, B.; Sabel, N.; Robertson, A. Can molar incisor hypomineralization cause dental fear and anxiety or influence the oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents?-a systematic review. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 23, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyne, A.; Parekh, S.; Patel, N.; Lafferty, F.; Brown, C.; Rodd, H.; Monteiro, J. Patient-reported outcome measure for children and young people with amelogenesis imperfecta. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munsey, C. The kids aren’t all right. Monit Psychol 2010, 41, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bethell, C.; Jones, J.; Gombojav, N.; Linkenbach, J.; Sege, R. Positive childhood experiences and adult mental and relational health in a statewide sample: Associations across adverse childhood experiences levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e193007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodd, H.; Timms, L.; Noble, F.; Bux, S.; Porritt, J.; Marshman, Z. ‘Message to Dentist’: Facilitating Communication with Dentally Anxious Children. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qabool, H.; Sukhia, R.H.; Fida, M. Assessment of cooperation and compliance in adult patients at three stages of orthodontic treatment at a tertiary care hospital: A cross-sectional study. Int. Orthod. 2020, 18, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshman, Z. ‘Your teeth you are in control’. BDJ Team 2017, 4, 17010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, L.; Dewa, C.S.; El-Badrawy, W.; Nainar, S.H. Occupational burnout and depression among paediatric dentists in the United States. Int. J. Paed. Dent. 2020, 30, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tates, K.; Meeuwesen, L. Doctor–parent–child communication. A review of the literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, R. Storytelling, sugar snacking, and toothbrushing rules: A proposed theoretical and developmental perspective on children’s health and oral health literacy. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 25, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Humphris, G.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Ross, A.; Freeman, R. Communication strategies to encourage child participation in an oral health promotion session: An exemplar video observational study. Health Expect 2021, 24, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Humphris, G.; Ross, A.; MacPherson, L.; Freeman, R. Recording communication in primary dental practice: An exploratory study of interactions between dental health professionals, children and parents. Br. Dental. J. 2019, 227, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Humphris, G.; MacPherson, L.; Ross, A.; Freeman, R. Development of an interaction coding scheme (PaeD-TrICS) to record the triadic communication behaviours in preventive dental consultations with preschool child patients and families: A video- based observational study. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Humphris, G.M. Reassurance and distress behavior in pre- school children undergoing dental preventive care procedures in a community setting: A multilevel observational study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 48, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczak, M.; Raes, M.E.; Avalosse, H.; Roskam, I. Exhausted Parents: Sociodemographic, Child-Related, Parent-Related, Parenting and Family-Functioning Correlates of Parental Burnout. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavic, L.; Tadin, A.; Matkovic, A.; Gorseta, K.; Sidhu, S.K. The association of parental dental anxiety and knowledge of caries preventive measures with psychological profiles and children’s oral health. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 23, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Cooperative | Reasonably relaxed. Minimal apprehension and may even be enthusiastic. Acceptance of treatment, at times cautious, willingness to comply with the dentist, at times with reservation but follows the dentist’s directions. Can be treated by a straightforward, behaviour-shaping approach. When guidelines for behaviour are established, these children perform within the framework provided. |

| Lacking cooperative ability (Pre-cooperative) | Very young children with whom communication cannot be established. Comprehension cannot be expected. Lack cooperative abilities usually because of their age. For pre-cooperative children, time usually solves the behaviour problems. As they grow older, they develop into cooperative dental patients and treatment is provided with behaviour shaping. Another group of children who lack cooperative ability is those with specific debilitating or disabling conditions. The severity of the child’s condition prohibits cooperation in the usual manner. Although special behaviour guidance techniques are used to allow treatment to be carried out, immediate major positive behavioural changes cannot be expected. |

| Potentially cooperative | Previously referred to as ‘uncooperative’ or ‘non-cooperative’. This type of behaviour differs from that of children lacking cooperative ability because these children have the capability to perform cooperatively. They have the capacity to cooperate but choose not to—this is an important distinction. They are potentially the most challenging (and most common) patients you are going to meet. When a child is characterised as potentially cooperative, clinical judgment is that the child’s behaviour can be modified; that is, the child can become cooperative. The adverse reactions have been given specific labels for descriptions of potentially cooperative patients, so that potentially cooperative group are further categorised as follows:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donnell, C.C. Classifying Children’s Behaviour at the Dentist—What about ‘Burnout’? Dent. J. 2023, 11, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11030070

Donnell CC. Classifying Children’s Behaviour at the Dentist—What about ‘Burnout’? Dentistry Journal. 2023; 11(3):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11030070

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonnell, Christopher C. 2023. "Classifying Children’s Behaviour at the Dentist—What about ‘Burnout’?" Dentistry Journal 11, no. 3: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11030070

APA StyleDonnell, C. C. (2023). Classifying Children’s Behaviour at the Dentist—What about ‘Burnout’? Dentistry Journal, 11(3), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11030070