Abstract

(1) Background: This systematic review aimed to evaluate the effects of laser therapy on radiographic bone level (RBL) changes in peri-implantitis defects. (2) Methods: A literature search with defined inclusion criteria was performed. PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar were searched through September 2020. The evaluated primary outcomes were RBL changes. In studies that reported RBL data, corresponding secondary clinical outcomes were probing depth (PD), bleeding on probing (BOP), and clinical attachment level (CAL). (3) Results: Thirteen articles were selected for data extraction and risk of bias assessment. Eight studies showed evidence of RBL gain in the laser groups compared to baseline, but did not report the statistical significance. Eight of these 13 studies reported comparisons to control. Five of the eight studies did not show RBL gain in the laser groups compared to control. In the laser groups compared to baseline, 11 of 13 reported reduced PD, and 6 of 13 reported significantly reduced BOP. Compared to the control, eight of the eight reported reduction of PD, and three of six reported significantly reduced BOP. Statistical significance was not consistently reported. (4) Conclusions: Within the limits of this systematic review, laser treatment may promote bone gain in peri-implantitis defects, may reduce BOP and PDs, and may be comparable to mechanical therapy. However, definitive conclusions can only be made with statistically significant data, which were found lacking in the currently available studies. This systematic review was registered with the National Institute for Health Research, international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42020207972.

Keywords:

systematic review; peri-implant disease; peri-implantitis; laser; radiographic; radiograph 1. Introduction

The increasing usage of implants to rehabilitate the edentulous alveolar ridge has led to the higher frequency of peri-implant diseases, classified as peri-implant mucositis or peri-implantitis [1,2]. Peri-implant mucositis is a reversible inflammatory lesion that occurs in the soft tissues surrounding the endosseous dental implants [3]. Untreated peri-implant mucositis develops a radiographic progressive bone loss around the osseointegrated implant, resulting in peri-implantitis [4,5]. The progression of peri-implantitis is non-linear and accelerating; it manifests as a circumferential pattern of bone loss apical to the implant platform [5]. The weighted mean prevalence of peri-implantitis has been estimated at 22% [6]. The primary etiology of peri-implant diseases is microbial biofilm [5]. An increased risk of peri-implantitis is reported in patients with a previous history of chronic periodontitis, poor periodontal maintenance compliance, and inadequate plaque control [5,7].

No single peri-implantitis treatment protocol is recognized, despite the availability of several treatment options. Treatment alternatives include non-surgical therapy with and without adjunctive use of local delivery antibiotics, lasers, and surgical therapy [7]. Non-surgical therapy consists of mechanical debridement (MD) of implant surfaces [8]. However, conventional mechanical therapy leads to increased roughness of the implant surface and oral pathogen retention. Mechanical therapy with adjunctive use of local antibiotics can reduce bleeding on probing (BOP) and probing depth (PD) [9]. The goal of surgical therapy is to create access for the debridement and decontamination of the implant surface [10]. Guided bone regeneration techniques have been used to enhance bone fill in peri-implant defects [11].

Laser therapy is bactericidal, does not alter the implant surface morphology when used properly, and can induce new bone formation [12]. Various laser systems, such as diode, neodymium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG), erbium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Er:YAG), and carbon dioxide (CO2), have been used for the treatment of peri-implantitis [13]. CO2 and diode lasers have been used for the decontamination of the implant surface [14,15]. Nd:YAG and Er:YAG lasers at low-intensity have bactericidal effects [16,17]. Er:YAG lasers have been utilized in both surgical and non-surgical therapy [18,19,20,21,22]. Therefore, when used to decontaminate and regenerate peri-implant bone defects, dental lasers may be a viable option for positively affecting RBL changes during peri-implantitis treatment. The aim of this review is to systematically evaluate the effect of high-intensity laser therapy on peri-implantitis defects by assessing the bone changes using radiographic methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focus Question

What is the radiographic osseous response in peri-implant defects after laser-assisted peri-implantitis treatment? The following were addressed in this focus question (PICOS): Participants: humans diagnosed with peri-implantitis; Interventions: laser-assisted peri-implantitis therapy; Comparisons: treated sites vs. control/baseline; Outcomes: (1) primary: RBL changes, (2) secondary: CAL, BOP, PD; and Study design: descriptive studies. High-intensity laser usage that results in ablation and removal of gingival crevicular epithelium is categorized as a surgical treatment.

2.2. Literature Search and Study Design

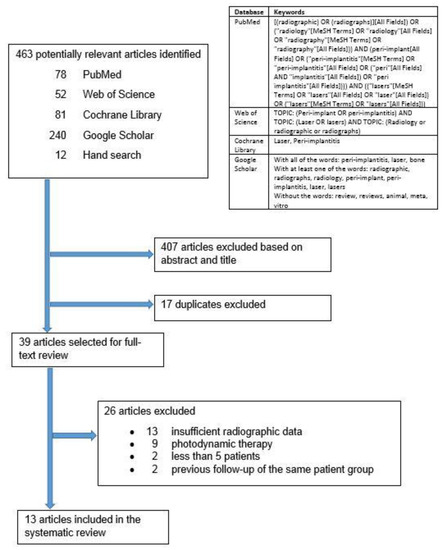

The electronic databases PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar were searched up to September 2020 (Figure 1). Google Scholar was also searched for gray literature. Additional hand searching of laser-related research was performed on the reference list of the selected articles. Experts in the field of dental laser-related research were consulted for additional articles. Corresponding authors of the selected articles were contacted to request any additional radiographic data or information regarding their studies and to suggest relevant new articles. Corresponding authors who responded did not provide any additional data. This systematic review was registered with the National Institute for Health Research, international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42020207972. There were no amendments to the submitted protocol. This systematic review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.

Figure 1.

Search strategy.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

- Patients diagnosed with peri-implantitis, reported as inflamed peri-implant pockets 4 mm or more in depth and/or loss of supporting peri-implant bone, were included.

- Clinical studies with high-intensity laser therapy of peri-implant defects were included. High intensity laser usage that results in ablation and removal of gingival crevicular epithelium were categorized as surgical treatments.

- Studies with sufficient radiographic data for at least five patients were included.

- Clinical trials reporting radiographic effects of laser treatment on human peri-implant diseased periodontium were included.

- Non-English articles were included, but were selected for full-text analysis only if an English translation were available.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

- All in vitro, cadaver, and animal studies were excluded.

- Photodynamic therapy studies were excluded.

- Non-surgical studies with low-intensity laser therapy that do not result in ablation or removal of gingival epithelium were excluded.

- Conference abstracts and posters were excluded.

2.5. Screening, Selection, and Data Extraction

Three reviewers (LSA, JGS, and MT) independently screened the “Title and Abstract”. Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Articles were included for full-text screening if there were any doubt. The full text was then independently analyzed by the three reviewers (LSA, JGS, and MT). Data extraction of final selected articles was also independently performed by the same three reviewers with a previous pilot-tested data extraction sheet. The independently extracted data were cross-referenced among reviewers for accuracy and completeness. All disagreements pertaining to the literature screening, selection, and data extraction were resolved by discussion with a fourth reviewer (JBS). The evaluated primary outcome was RBL changes, and only studies that reported this were included. The corresponding secondary clinical outcomes PD, BOP, and CAL were also reported for these included studies.

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias (Table 1) was assessed using the risk of bias tool by the Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) [23]. The same three reviewers (LSA, JGS, and MT) independently scored the risk of bias, and disagreements were resolved through discussion with a fourth reviewer (AP).

Table 1.

OHAT risk of bias analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

The search yielded 463 reviews: 78 in PubMed, 52 in Web of Science, 81 in Cochrane Library, 240 in Google Scholar, and 12 from hand search (Figure 1). After the title and abstract screening, the duplicates were removed, and 39 articles remained for full-text analysis. After full-text analysis, 26 were eliminated: 13 for having insufficient radiographic data [18,21,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], nine for focusing on photodynamic therapy [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53], two for less than five patients [54,55], and two for being previous follow up publications of the same patient group [20,56]. Only 13 articles remained for data extraction (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8).

Table 2.

Study design and details.

Table 3.

Laser details and protocol.

Table 4.

Clinical therapy.

Table 5.

Implant details and restorative management.

Table 6.

Radiographic methods and outcomes.

Table 7.

Other clinical parameters and outcomes.

Table 8.

Clinical significance of laser therapy ≥ 6 months follow-up.

3.2. Quality of Evidence

The risk of bias (Table 1) of the selected six randomized trials [19,22,24,25,32,33] were mostly “definitely or probably low risk of bias”, and the risk of bias for the other seven non-randomized studies [14,26,27,28,29,30,31] scored varying degrees of bias ranging from “definitely high risk to definitely low risk of bias”. In these seven studies, the increase in scoring of “probably high risk of bias” was due to failure to report details of the study protocol (Table 1). Of these seven studies, four studies were at “definitely high risk of bias” for detection bias [27,31] or selective reporting bias [29,30]. As approximately two-thirds of the included studies were “definitely low risk of bias” to “probably high risk of bias”, the overall level of evidence level of this systematic review is moderate to low. All selected radiographic studies utilized baseline or control for comparison. However, there was limited quantitative data to enable a meaningful meta-analysis. The selected studies with controls were too heterogenous, and these studies utilized different lasers and had different treatment protocols and follow-up periods.

3.3. Study Characteristics

Of the 13 studies (Table 2), one was retrospective [30] and 12 were prospective [14,19,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,31,32,33]. Of the 12 prospective studies, eight were controlled trials [19,22,24,25,28,29,32,33]. Of the eight controlled trials, six were randomized [19,22,24,25,32,33]. The duration of the selected studies ranged from 3 months to 16 years. Four studies [26,28,29,31] reported implant loss during the duration of observation. Implant survival post-laser therapy reported in these four studies were 86.4% (19 of 22 implants) for up to a 3-year observation period [28], 96.0% (24 of 25 implants; for the one patient with two implants who dropped out after 3 months, the implant survival was unknown and was excluded from the calculation) for a 1-year observation period [31], 88.2% (15 of 17 implants) for a 12-year observation period [26], and 76.5% (13 of 17 implants in the laser and bone augmentation group) and 90.9% (20 of 22 implants in the laser and soft tissue resection group) for up to a 5-year observation period [29]. Two studies reported no implants were lost during the observation period and a 100% implant survival [22,32]. The remaining seven studies may have had 100% implant survival post-treatment as implant loss was not reported during the observation period. The sample size of the selected studies ranged from 10 patients to 68 patients. The age range of the patients was 20 to 85 years. The health status of the included patients was mostly not specified or systemically healthy. Other clinical parameters evaluated were: plaque index, bleeding on probing, probing pocket depth, suppuration, microbial analysis, width of keratinized tissue, peri-implant bone loss, and radiographic analysis.

Of the laser types evaluated in 13 studies (Table 3), two were diode (810 nm) [25,26], two were Nd:YAG (1064 nm) [24,30], six were Er:YAG (2940 nm) [19,22,27,31,32,33], and three were CO2 (10,600 nm) [14,28,29]. On the method of use, 8 of the 13 studies elevated a full-thickness flap before using the laser [14,26,27,28,29,31,32,33]. Cooling used during laser treatment was water for three studies [19,27,32], air and water for one study [24], or not specified for nine studies [14,22,25,26,28,29,30,31,33]. Nine studies [19,22,24,25,27,30,31,32,33] specified pulsed lasers, two specified continuous-wave laser emission [28,29], and two did not specify the emission mode [14,26]. Twelve studies [14,19,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,31,32,33] reported laser power or energy parameters, and one did not specify parameters [30]. Eight studies [14,19,24,25,26,28,29,33] specified laser irradiation exposure duration, and five did not specify duration [22,27,30,31,32]. Six studies [22,27,30,31,32,33] disclosed commercial support, four disclosed support from an educational institution or society [19,24,25,33], and four provided no disclosure [14,26,28,32].

Of the selected studies (Table 4), five had no control [14,26,27,30,31], two had controls that were non-surgical mechanical debridement [24,25], two had controls that were non-surgical mechanical and chemical debridement [19,32], two had controls that were decontamination with air-powder abrasives [22,28], one had a control that was soft tissue resection [29], and one had a control that was surgical regenerative therapy including mechanical debridement [33]. Before laser treatment, six studies [19,24,25,26,32,33] used nonsurgical mechanical intervention, one used systemic antimicrobial therapy [27], two used antimicrobial oral rinses [28,29], and four had no additional intervention [14,22,30,31]. Of the 13 studies, four had no conjunctive surgical therapy [19,22,24,25] and nine had surgical therapy in conjunction with laser therapy [14,26,27,29,31,32,33]. In addition to the laser treatment, seven studies [14,26,27,29,31,32,33] used bone grafting biomaterials, three did not mention biomaterials [19,22,28], and three did not use any grafting materials [24,25,30]. Of the selected studies, four reported use of systemic antibiotics [27,30,32,33], three reported pre-operative use of antimicrobial irrigant [26,28,29], four reported intra-operative use of antimicrobial irrigant [19,25,27,30], and six reported post-operative use of antimicrobial irrigant [19,27,30,31,32,33].

Implant types included in the studies included a wide range of manufacturers and different implant surfaces (Table 5). Four studies described the loading protocol after laser treatment [14,22,24,29], and this was not mentioned in the other nine studies [19,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,33]. Duration of implant function before peri-implantitis treatment ranged from 3 months to more than 15 years. The implant crowns were cemented in two studies [24,25], cemented or screw-retained in two studies [27,29], and method of retention was not mentioned in nine studies [14,19,22,26,28,30,31,32,33]. Occlusal adjustments were described in two studies [25,30], and were not mentioned [14,19,22,26,28,33] or not done in the other 11 studies [24,27,29,31,32]. Implant superstructures were removed in three studies [22,25,32], screw-retained prostheses were removed but cemented prostheses were left in situ in one study [29], and in the other nine studies, removal was either not mentioned or not done [14,19,24,26,27,28,30,31,33]. Implantoplasty was reported or shown in two studies [28,33], and was not mentioned [14,19,22,26] or not done [24,25,27,29,30,31,32] in the other 11 studies.

3.4. Primary Outcomes

With respect to radiographic assessment (Table 6 and Table 8), nine studies had radiographic standardization [22,24,25,27,28,29,31,32,33], and the remaining four did not mention or use standardization [14,19,26,30]. Five studies performed radiographic follow-up at 6 months [22,24,25,32,33], and the remaining eight studies did so at one year and later [14,19,26,27,28,29,30,31]. For radiographic outcome compared to baseline, three studies had statistically significant RBL gain [25,28,29], two reported no significant difference [22,24], and eight studies either did no statistical analysis or did not mention it [14,19,26,27,30,31,32,33]. As for radiographic outcome compared to control, two studies had significant RBL gain [28,29], four studies had no significant difference [19,22,24,33], one study had significant RBL loss [25], one study did not report statistical analysis [32], and five studies had no controls [14,26,27,30,31].

For RBL compared to baseline, the Nd:YAG laser had no significant effect in one study [24] and RBL gain in another study [30] with no statistical analysis; the diode laser had significant RBL loss in one study [25], and RBL gain in another study [26] where the significance was not analyzed; the Er:YAG laser did not significantly affect RBL in two studies [19,22] and in the other studies the RBL loss (one study) [32] or gain (three studies) [27,31,33] was not statistically analyzed; and the CO2 laser studies reported RBL gain that was not statistically analyzed [14,28,29]. Compared to control, the Nd:YAG (one study) [24] did not have a significant effect on the RBL; the diode laser had significant RBL loss in one study [25]; the Er:YAG laser did not significantly affect RBL in three studies [19,22,33], and in another study [32] the reduced RBL loss was not statistically analyzed; and the CO2 laser showed significant RBL gain in two studies [28,29] and no significant difference in another [29].

This systematic review, parsed by laser wavelength, revealed the following:

- For the two diode laser studies, one reported RBL gain compared to baseline [26], but the statistical significance was not analyzed. The other reported significant RBL loss compared to baseline and control [25].

- For the two Nd:YAG laser investigations, one showed RBL gain [30] compared to baseline, but without analysis of statistical significance. The other [24] indicated RBL loss compared to baseline and control that was not statistically significant.

- For the five Er:YAG laser studies, two reported RBL gain [27,31] compared to baseline but did not analyze the statistical significance of the change. One study [32] showed RBL loss compared to baseline and less RBL loss compared to control; the statistical significance of both results was not analyzed. Another reported RBL loss compared to baseline and control that was not significant [22]. One investigation reported no significant RBL change compared to either baseline or control [19]. Another study [33] reported RBL gain compared to control that was not significant, and RBL gain compared to baseline without analyzing the significance.

- For the three CO2 laser studies, two [28,29] reported RBL gain compared to baseline (statistical significance not analyzed) and significant RBL gain compared to control. The other study [14] reported RBL gain compared to baseline, but did not analyze the statistical significance.

Overall, the 13 studies revealed conflicting results for changes in bony defects. Eight studies showed evidence of RBL gain compared to baseline [14,26,27,28,29,30,31,33] and two showed evidence of RBL loss [25,32]. The statistical significance of the RBL changes was not analyzed in nine of these ten studies [14,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Three reported no statistically significant change from baseline [19,22,24].

Eight of 13 studies reported comparisons to control [19,22,24,25,28,29,32,33]. Of these eight studies, three showed RBL gain compared to control [28,29,33]; in two of these three studies RBL gain was statistically significant [28,29], and one was not significant [33]. The two studies [28,29] that showed statistically significant RBL gain compared to control were CO2 laser treatments compared to air abrasives by the same research group. As for the remaining five of these eight studies, two reported RBL loss that was not statistically significant [22,24], one reported no statistically significant RBL changes [19], one reported significant RBL loss [25], and one reported less RBL loss with no statistical analysis [32].

3.5. Secondary Outcomes

Comparing BOP to baseline (Table 7 and Table 8), six studies reported significant reduction [14,19,22,25,32,33], two analyzed significance but did not report it [24,27], and five did no statistical analysis [26,28,29,30,31]. Comparing BOP to control, six studies did statistical analysis [19,22,24,25,32,33], of which three reported significant BOP decrease [19,24,32], and three no difference [22,25,33]; of the remaining seven studies, five had no controls [14,26,27,30,31] and two provided no statistical analysis [28,29]. As for CAL compared to baseline, three studies reported significant improvement [19,28,33] and one reported attachment loss but no statistical analysis [29], and the remaining nine studies did not assess [24,25,27,31,32] or mention [14,22,26,30] it. As for CAL compared to control, of the four studies that did statistical analysis [19,28,29,33], two found significant improvement [28,29] and two did not find any difference [19,33]. Of the remaining nine studies, five had no control [14,26,27,30,31] and four did not evaluate or report [22,24,25,32]. As for PD compared to baseline, five studies reported statistically significant improvement [14,19,25,27,33]. Of the remaining eight studies [22,24,26,28,29,30,31,32], seven presented changes in PD but no statistical analysis was done or reported [22,24,28,29,30,31,32] and one did not assess PD [26]. As for PD compared to control, five studies reported statistical analysis [19,22,24,25,33], two showed significant improvement [24,33], and three reported no significant difference [19,22,25]. Of the remaining eight studies [14,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], five had no controls [14,26,27,30,31], two did no statistical analysis [28,29], and one did not mention [32]. Two studies conducted a microbial analysis: one study reported almost complete elimination of Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) [26] and one did not find a significant difference [25]. For the remaining 11 studies, microbial analysis was not done or mentioned. As for adverse reactions, two studies reported no adverse reactions [25,28], four reported some minor adverse reactions [14,19,22,29], one study reported that membrane exposure significantly reduced PD reduction and CAL gain [33], and the remaining six studies did not mention [24,26,27,30,31,32].

The clinical significance of laser therapy using different lasers is described in Table 8. Laser therapy was compared to baseline or control. Control was either mechanical debridement with curettes or air-powder abrasives.

Inflammation was evaluated via BOP, sulcus bleeding index (SBI), or suppuration. Compared to baseline, the Nd:YAG laser reduced inflammation in one study [24], although the significance was not analyzed; the diode laser had no significant effect on inflammation as reported in one study [25]; the Er:YAG laser significantly reduced inflammation in four studies [19,22,32,33] and in one study the reduction was not statistically analyzed [31]; and for the CO2 laser, inflammation was significantly reduced in one study [14], and in two studies [28,29] the increase in inflammation was not statistically analyzed. The remaining three studies did not report inflammatory parameters [26,27,30]. Compared to control, the Nd:YAG (one study) [24] and the diode laser (one study) [25] did not have a significant effect on inflammation; the Er:YAG significantly reduced inflammation in two studies [19,32], and was not statistically significant in two studies [22,33]; and for the CO2 lasers, the increase in inflammation in one study [28] was not statistically analyzed, and in one other study [29] the increase in the residual bone group or the decrease in the augmented bone group was not statistically analyzed.

For PD compared to baseline, the Nd:YAG laser reduced PD in one study [24] with no reported statistical analysis; the diode laser significantly reduced the PD in one study [25]; the Er:YAG laser significantly reduced PD in three studies [19,27,33] and in three studies [22,31,32] the reduction was not statistically analyzed; and for the CO2 laser, PD was significantly reduced in one study [14], and in two studies [28,29] the increase was not statistically analyzed. Compared to control, the Nd:YAG (one study) [24] and the diode laser (one study) [25] did not have a significant effect on the PD; the Er:YAG laser significantly reduced PD in one study [33], did not significantly affect PD in two studies [19,22], and in another study [32] the reduction was not statistically analyzed; and for the CO2 laser, the reduction in PD in two studies [28,29] and the insignificant change in PD in one study [29] were not statistically analyzed.

4. Discussion

Periodontal regeneration, defined by the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and published by several investigators [58], is the restoration of lost or diminished periodontal tissues including cementum, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. Human histological studies are the only way to assess periodontal regeneration. Osseointegrated dental implants lack cementum and periodontal ligament, so a direct comparison between teeth and implants is not possible. Histological evaluation of regeneration has been the most accurate way to evaluate regeneration around teeth [59,60]. To date, few clinical studies have reported histological outcomes after laser treatment of peri-implantitis, and these were conducted in dogs [61,62]; therefore, RBL changes post-laser treatment may be the next available option to infer histologic changes. Radiographic evaluation of bone fill and increase in radio-opacity post-treatment may indicate regeneration or repair and may be a possible way to infer regeneration or repair when bone grafting material is not used in conjunction with the laser treatment. The selected studies in this systematic review are focused on the radiographic methodology and post-treatment changes to evaluate whether laser treatment can provide positive outcomes. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis on laser treatment of peri-implantitis reported only three studies [22,25,29] for RBL changes using high-intensity laser therapy [63]. These three studies are included in the 13 studies analyzed in this review.

Positive radiographic interpretation can be bone fill around implants after peri-implantitis treatment. Radiographic determination of bone changes around implants and teeth can be limited by non-standardized radiologic methodology with inconsistent sensor angulations, position, and sensitivity [64]. In some of the included studies, efforts to standardize radiographs were not mentioned [14,19,30] or done. In addition, methods to assess bone gain or loss were different in different studies.

Clinician interpretation of radiographs can be subjective and biased. The level of expertise of the clinician when taking or interpreting radiographs may vary from radiologist, dentist, or dental student, thus affecting the accuracy and consistency of the interpretation. Computer software-assisted radiographic assessment can be reproducible and reduce operator bias and inter-operator discrepancy [64,65]. However, not all the selected studies used software. The use of software is also not without limitations. The accuracy of software is dependent on operator calibration of the computer to a fixed structure in the mouth; thus, operator errors or calibration errors while using the software can also limit the accuracy of the results.

Radiographic evaluation can be limited by inter-patient variations. Different patients may have different rates and degrees of osseous healing and radio-opacity. In addition, different patients may have different bone and tissue density that may absorb radiation differently [66]: even within the same patient, slight changes in tissue remodeling at pre-treatment and post-treatment time points may affect the exact comparison of radiographs [67]. The time points at which the radiographs were taken may also have an impact on the radio-opacity of the bone fill. When radiographic evaluation is done too early (1 to 3 months), it may provide an erroneous impression that bone fill was not significant. Moreover, documented studies on the degree of calcification of bone before it becomes radiographically apparent have reported time intervals of at least 6 months post-therapy [68]. Most studies were not clear as to which time interval would best reflect bone fill, and in some cases, non-significant results may be the result of insufficient time allocated for the bone changes to be mineralized adequately to show radiographically. In addition, most of the selected studies have inconsistent follow-up time intervals and missing radiographic evaluation at certain follow-up intervals.

The clinical effects of laser treatment at more than 6 months also show promise for radiographic outcomes, probing pocket depth changes, and control of inflammation, as most of the selected studies reported reduction in PD [14,19,22,24,25,27,28,29,31,32,33] and inflammation [14,19,22,24,29,31,33] compared to baseline (Table 8). When compared to control, many of the selected studies with controls reported positive radiographic outcomes [28,29,33], probing depth [28,29,32,33], and inflammation reduction [19,32,33], and that laser peri-implantitis treatment was as good as or possibly better than control. However, because significance was not analyzed in most of these studies, the results can only suggest a positive outcome but cannot definitively conclude that outcome is indeed statistically significant.

The risk of bias of the included studies was variable. A quarter of the studies showed definitely or probably low risk of bias; the rest were mixed, with approximately a third of the studies showing 1–2 points at definitely high risk of bias. However, the assessment of the risk of bias alone may not be sufficient to fully assess the body of evidence. The quality of evidence can be compromised by a number of potential biases. For example, 8 of the 13 studies either did not include or report on the statistical significance of radiographic bone level changes, thus showing a level of possible reporting bias [14,19,26,27,30,31,32,33]. Only two-thirds of the six randomized controlled trials included in this systematic review calculated the number of patients required for an adequately powered trial [22,24,25,33], thus revealing a potential imprecision bias in the other two trials [19,32]. A commercial bias may apply to 10 of the 13 studies that either reported some degree of industry sponsorship [22,27,29,30,31,33] or provided no disclosure [14,26,28,32].

A possible limitation of the review process was that the keywords used in the search may have excluded articles published in a foreign language, hence some pertinent articles may have been missed.

The evidence presented in this systematic review was also constrained by insufficient standardization of data reported in the selected articles. This shortcoming can lead to confounding factors that may influence the results of this review. In addition, variability in the detected bias among the chosen papers further limited the strength of the data synthesis. Nevertheless, this review accurately reported the variables identified in the studies in order to establish a baseline of understanding of how adjunctive laser use during treatment of peri-implantitis may affect radiographic bone level changes.

Conventional surgical therapies are demanding, technique-sensitive, and time consuming. Laser therapies may reduce clinician fatigue and stress while resulting in positive clinical outcomes. Further research studies will provide more tangible clinical data on the specific type of lasers and their associated clinical outcomes.

4.1. Recommendations for Laser Treatment Protocols

For the treatment for peri-implantitis with dental lasers, the researcher and clinician should consider laser treatment protocols that have shown evidence of the following: (1) laser reduction of infection, peri-implant bacteria, or viruses; (2) laser reduction of inflammation or inflammatory cytokines; (3) minimal tissue necrosis; (4) biostimulatory or enhanced laser-induced healing; and (5) consideration for adjunctive non-laser (mechanical debridement, air abrasives, or topical chemical agents) and laser approaches for implant rescue. To ensure safe use of the laser for patient treatment, the clinician should be well educated in dental lasers and abide by the laser guidelines and protocols of the manufacturer.

4.2. Recommendations for Future Studies

Recommendations for future research should include careful documentation of all collected data (Table 9) to facilitate meta-analyses of systematic reviews. In the conduct of a study, every attempt should be made to evaluate for statistical significance.

Table 9.

Recommendations for future studies.

Table 9 was specifically devised as a suggested guideline to enable future investigators to: (1) consider the range of variables applicable to laser-based peri-implantitis treatment, (2) develop more consistent study designs with greater reproducibility, (3) improve standardization in data collection, (4) increase the validity of research findings, (5) reduce occurrences of bias, and (6) assure greater relevance and translation of research findings to the clinician.

5. Conclusions

The statistical significance of the RBL changes was not analyzed in most of the 13 studies; therefore, definitive RBL gain remains inconclusive. However, the use of dental lasers to encourage radiographic bone fill may show some promise, as most studies reported bone gain compared to baseline or control. The following conclusions about dental lasers in the treatment of peri-implantitis are within the limits of this systematic review: (1) laser treatment may enhance bone gain in peri-implantitis defects, (2) laser treatment may reduce BOP and PDs, and (3) laser peri-implantitis treatment may be as good as if not better than mechanical debridement or air abrasives. Unfortunately, definitive conclusions can only be made with proper statistical analysis of the bone level changes, which was lacking in the currently available studies. Further studies with an emphasis on supporting statistics are needed. Table 9 outlines the research data needed to aid future systematic reviews on laser treatment of peri-implantitis.

Author Contributions

M.T. participated in the design of the study, literature search and article selection, acquisition and analysis of data, and drafting and revising of manuscript and tables. L.S.C.A. participated in the design of the study, literature search and article selection, acquisition and analysis of data, and drafting and revising of manuscript and tables. J.G.S. participated in the design of the study, literature search and article selection, acquisition and analysis of data, and drafting and revising of manuscript and tables. J.B.S. participated in the design of the study, article selection, and drafting and revising of manuscript and tables. A.P.B.d.S. participated in the design of the study, article selection, and drafting and revising of manuscript and tables. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This systematic review received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this systematic review are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Albrektsson, T.; Isidor, F. Consensus Report of Session IV. In Proceedings of the 1st European Workshop on Periodontology, Charter House of Ittingen, Thurgau, Switzerland, 1–4 February 1993; Lang, N.P., Karring, T., Eds.; Quintessence: London, UK, 1994; pp. 365–369, ISBN 1-85097-035-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lindhe, J.; Meyle, J.; Group D of European Workshop on Periodontology. Peri-Implant Diseases: Consensus Report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heitz-Mayfield, L.J.A.; Salvi, G.E. Peri-Implant Mucositis. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S257–S266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zitzmann, N.U.; Berglundh, T. Definition and Prevalence of Peri-Implant Diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, F.; Derks, J.; Monje, A.; Wang, H.L. Peri-Implantitis. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S267–S290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, J.; Tomasi, C. Peri-Implant Health and Disease. A Systematic Review of Current Epidemiology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, S158–S171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, M.; Craig, J.; Balkin, B.E.; Suzuki, J.B. Peri-Implantitis: A Comprehensive Overview of Systematic Reviews. J. Oral Implantol. 2018, 44, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos, G.E.; Javed, F.; Delgado-Ruiz, R.A.; Calvo-Guirado, J.L. Peri-Implant Diseases: A Review of Treatment Interventions. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 59, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renvert, S.; Roos-Jansåker, A.M.; Claffey, N. Non-Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implant Mucositis and Peri-Implantitis: A Literature Review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claffey, N.; Clarke, E.; Polyzois, I.; Renvert, S. Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schou, S.; Holmstrup, P.; Jørgensen, T.; Skovgaard, L.T.; Stoltze, K.; Hjorting-Hansen, E.; Wenzel, A. Anorganic Porous Bovine-Derived Bone Mineral (Bio-Oss) and ePTFE Membrane in the Treatment of Peri-Implantitis in Cynomolgus Monkeys. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2003, 14, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, K.; Aoki, A.; Coluzzi, D.; Yukna, R.; Wang, C.Y.; Pavlic, V.; Izumi, Y. Lasers in Minimally Invasive Periodontal and Peri-Implant Therapy. Periodontology 2000 2016, 71, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, I.; Aoki, A.; Takasaki, A.A.; Mizutani, K.; Sasaki, K.M.; Izumi, Y. Application of Lasers in Periodontics: True Innovation or Myth? Periodontology 2000 2009, 50, 90–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanos, G.E.; Nentwig, G.H. Regenerative Therapy of Deep Peri-Implant Infrabony Defects After CO2 Laser Implant Surface Decontamination. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2008, 28, 245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Romanos, G.E.; Everts, H.; Nentwig, G.H. Effects of Diode and Nd:YAG Laser Irradiation on Titanium Discs: A Scanning Electron Microscope Examination. J. Periodontol. 2000, 71, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannini, R.; Vassalli, M.; Chellini, F.; Polidori, L.; Dei, R.; Giannelli, M. Neodymium:Yttrium Aluminum Garnet Laser Irradiation with Low Pulse Energy: A Potential Tool for the Treatment of Peri-Implant Disease. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2006, 17, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreisler, M.; Götz, H.; Duschner, H.; d’Hoedt, B. Effect of Nd:YAG, Ho:YAG, Er:YAG, CO2, and GaAIAs Laser Irradiation on Surface Properties of Endosseous Dental Implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2002, 17, 202–211. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, F.; Bieling, K.; Nuesry, E.; Sculean, A.; Becker, J. Clinical and Histological Healing Pattern of Peri-Implantitis Lesions Following Non-Surgical Treatment with an Er:YAG Laser. Lasers Surg. Med. 2006, 38, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Bieling, K.; Bonsmann, M.; Latz, T.; Becker, J. Nonsurgical Treatment of Moderate and Advanced Periimplantitis Lesions: A Controlled Clinical Study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2006, 10, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Sahm, N.; Iglhaut, G.; Becker, J. Impact of the Method of Surface Debridement and Decontamination on the Clinical Outcome Following Combined Surgical Therapy of Peri-Implantitis: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, G.R.; Roos-Jansåker, A.M.; Lindahl, C.; Renvert, S. Microbiologic Results After Non-Surgical Erbium-Doped:Yttrium, Aluminum, and Garnet Laser or Air-Abrasive Treatment of Peri-Implantitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Periodontol. 2011, 82, 1267–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renvert, S.; Lindahl, C.; Roos Jansåker, A.M.; Persson, G.R. Treatment of Peri-Implantitis Using an Er:YAG Laser or an Air-Abrasive Device: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, A.A.; Boyles, A.L.; Wolfe, M.S.; Bucher, J.R.; Thayer, K.A. Systematic Review and Evidence Integration for Literature-Based Environmental Health Science Assessments. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abduljabbar, T.; Javed, F.; Kellesarian, S.V.; Vohra, F.; Romanos, G.E. Effect of Nd:YAG Laser-Assisted Non-Surgical Mechanical Debridement on Clinical and Radiographic Peri-Implant Inflammatory Parameters in Patients with Peri-Implant Disease. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2017, 168, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arısan, V.; Karabuda, Z.C.; Arıcı, S.V.; Topçuoğlu, N.; Külekçi, G. A Randomized Clinical Trial of an Adjunct Diode Laser Application for the Nonsurgical Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2015, 33, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bach, G. Integration of Diode Laser Surface Decontamination in Periimplantitis Therapy—A Twelve Year Review of a Fit for Practice Concept. Laser 2009, 1, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Clem, D.; Gunsolley, J.C. Peri-Implantitis Treatment Using Er:YAG Laser and Bone Grafting. A Prospective Consecutive Case Series Evaluation: 1 Year Posttherapy. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2019, 39, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deppe, H.; Horch, H.H.; Greim, H.; Brill, T.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Donath, K. Peri-Implant Care with the CO2 Laser: In Vitro and In Vivo Results. Med. Laser Appl. 2005, 20, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppe, H.; Horch, H.H.; Neff, A. Conventional Versus CO2 Laser-Assisted Treatment of Peri-Implant Defects with the Concomitant Use of Pure-Phase Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate: A 5-Year Clinical Report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2007, 22, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, D.; Blodgett, K.; Braga, C.; Finkbeiner, L.; Fourrier, J.; George, J.; Gregg, R., II; Honigman, A.; Houser, B.; Lamas, W.; et al. Pulsed Nd:YAG Laser Treatment for Failing Dental Implants Due to Peri-Implantitis. In Lasers in Dentistry XX; Rechmann, P., Fried, D., Eds.; Proc. SPIE 8929; Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; p. 89290H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, M.R. Efficacy of Er:YAG Laser in the Decontamination of Peri-Implant Disease: A One-Year Prospective Closed Cohort Study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2017, 37, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, T.; Tomov, G. The Use of the Lite Touch Er:YAG Laser in Peri-Implantitis Treatment. Laser 2012, 4, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.W.; Ashnagar, S.; Gianfilippo, R.D.; Arnett, M.; Kinney, J.; Wang, H.L. Laser-Assisted Regenerative Surgical Therapy for Peri-Implantitis: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Periodontol. 2021, 92, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Falaki, R.; Cronshaw, M.; Hughes, F.J. Treatment Outcome Following Use of the Erbium, Chromium:Yttrium, Scandium, Gallium, Garnet Laser in the Non-Surgical Management of Peri-Implantitis: A Case Series. Br. Dent. J. 2014, 217, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, G.; Neckel, C.; Mall, C.; Krekeler, G. Conventional Versus Laser-Assisted Therapy of Periimplantitis: A Five-Year Comparative Study. Implant. Dent. 2000, 9, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, G.; Neckel, C.P. A 5-Year Comparative Study on Conventional and Laser Assisted Therapy of Periimplantitis and Periodontitis. In Lasers in Dentistry VI; Featherstone, J.D.B., Rechmann, P., Fried, D., Eds.; Proc. SPIE 3910; Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2000; pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Herten, M.; Sager, M.; Bieling, K.; Sculean, A.; Becker, J. Comparison of Naturally Occurring and Ligature-Induced Peri-Implantitis Bone Defects in Humans and Dogs. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2007, 18, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, F.; Hegewald, A.; John, G.; Sahm, N.; Becker, J. Four-Year Follow-Up of Combined Surgical Therapy of Advanced Peri-Implantitis Evaluating Two Methods of Surface Decontamination. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; John, G.; Schmucker, A.; Sahm, N.; Becker, J. Combined Surgical Therapy of Advanced Peri-Implantitis Evaluating Two Methods of Surface Decontamination: A 7-Year Follow-Up Observation. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.A.; Vouros, I.; Menexes, G.; Konstantinidis, A. The Utilization of a Diode Laser in the Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 1851–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Sahm, N.; Schwarz, K.; Becker, J. Impact of Defect Configuration on the Clinical Outcome Following Surgical Regenerative Therapy of Peri-Implantitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 37, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Sculean, A.; Rothamel, D.; Schwenzer, K.; Georg, T.; Becker, J. Clinical Evaluation of an Er:YAG Laser for Nonsurgical Treatment of Peri-Implantitis: A Pilot Study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2005, 16, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; John, G.; Mainusch, S.; Sahm, N.; Becker, J. Combined Surgical Therapy of Peri-Implantitis Evaluating Two Methods of Surface Debridement and Decontamination. A Two-Year Clinical Follow Up Report. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiorana, C.; Salina, S.; Santoro, F. Treatment of Periimplantitis with Diode Laser: A Clinical Report. J. Oral Laser Appl. 2002, 2, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti, M.; Schar, D.; Wicki, B.; Eick, S.; Ramseier, C.A.; Arweiler, N.B.; Sculean, A.; Salvi, G.E. Anti-Infective Therapy of Peri-Implantitis with Adjunctive Local Drug Delivery or Photodynamic Therapy: 12-Month Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2014, 25, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombeccari, G.P.; Guzzi, G.; Gualini, F.; Gualini, S.; Santoro, F.; Spadari, F. Photodynamic Therapy to Treat Periimplantitis. Implant. Dent. 2013, 22, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caccianiga, G.; Rey, G.; Baldoni, M.; Paiusco, A. Clinical, Radiographic and Microbiological Evaluation of High Level Laser Therapy, a New Photodynamic Therapy Protocol, in Peri-Implantitis Treatment; A Pilot Experience. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 6321906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deppe, H.; Mucke, T.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Kesting, M.; Sculean, A. Nonsurgical Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy in Moderate vs. Severe Peri-Implant Defects: A Clinical Pilot Study. Quintessence Int. 2013, 44, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörtbudak, O.; Haas, R.; Bernhart, T.; Mailath-Pokorny, G. Lethal Photosensitization for Decontamination of Implant Surfaces in the Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2001, 12, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haas, R.; Baron, M.; Dörtbudak, O.; Watzek, G. Lethal Photosensitization, Autogenous Bone, and e-PTFE Membrane for the Treatment of Peri-Implantitis: Preliminary Results. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2000, 15, 374–382. [Google Scholar]

- Poli, P.P.; Souza, F.A.; Ferrario, S.; Maiorana, C. Adjunctive Application of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy in the Prevention of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw Following Dentoalveolar Surgery: A Case Series. Photodiagnosis Photodyn 2019, 27, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, W.; Zhang, D.; Li, W.; Wang, Z. Adjunctive Photodynamic Therapy Improves the Outcomes of Peri-Implantitis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Aust. Dent. J. 2019, 64, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leretter, M.; Cândea, A.; Topala, F. Photodynamic Therapy in Peri-Implantitis. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Lasers in Medicine: Biotechnologies Integrated in Daily Medicine, Timisoara, Romania, 19–21 September 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncati, M.; Lucchese, A.; Carinci, F. Non-Surgical Treatment of Peri-Implantitis with the Adjunctive Use of an 810-nm Diode Laser. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2013, 17, 812–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatos, N.; Romanos, G.E.; Michaiel, M.; Sajadi, A.; Angelov, N.; Weltman, R. Management of Retrograde Peri-Implantitis Using an Air-Abrasive Device, Er, Cr: YSGG Laser, and Guided Bone Regeneration. Case Rep. Dent. 2018, 2018, 7283240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.-W. Laser-Assisted Regenerative Surgical Therapy for Peri-Implantitis. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03127228 (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Buser, D.; Weber, H.P.; Lang, N.P. Tissue Integration of Non-Submerged Implants. 1-Year Results of a Prospective Study with 100 ITI Hollow-Cylinder and Hollow-Screw Implants. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 1990, 1, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellonig, J.T.; Bowers, G.M. Regenerating Bone in Clinical Periodontics. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1990, 121, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevins, M.L.; Camelo, M.; Lynch, S.E.; Schenk, R.K.; Nevins, M. Evaluation of Periodontal Regeneration Following Grafting Intrabony Defects with Bio-Oss Collagen: A Human Histologic Report. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2003, 23, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yukna, R.A.; Carr, R.L.; Evans, G.H. Histologic Evaluation of an Nd:YAG Laser-Assisted New Attachment Procedure in Humans. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2007, 27, 577–587. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, F.; Jepsen, S.; Herten, M.; Sager, M.; Rothamel, D.; Becker, J. Influence of Different Treatment Approaches on Non-Submerged and Submerged Healing of Ligature Induced Peri-Implantitis Lesions: An Experimental Study in Dogs. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2006, 33, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevins, M.; Nevins, M.L.; Yamamoto, A.; Yoshino, T.; Ono, Y.; Wang, C.W.; Kim, D.M. Use of Er:YAG Laser to Decontaminate Infected Dental Implant Surface in Preparation for Reestablishment of Bone-to-Implant Contact. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2014, 34, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, G.H.; Suárez López Del Amo, F.; Wang, H.L. Laser Therapy for Treatment of Peri-Implant Mucositis and Peri-Implantitis: An American Academy of Periodontology Best Evidence Review. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 766–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, E. Radiographic and Digital Imaging in Periodontal Practice. J. Periodontol. 2000, 71, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nackaerts, O.; Jacobs, R.; Horner, K.; Zhao, F.; Lindh, C.; Karayianni, K.; van der Stelt, P.; Pavitt, S.; Devlin, H. Bone Density Measurements in Intra-Oral Radiographs. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2007, 11, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Jeong, S.H.; Kwon, T.G. Density of the Alveolar and Basal Bones of the Maxilla and the Mandible. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Xin, H.; Zang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y. The Remodeling of Alveolar Bone Supporting the Mandibular First Molar with Different Levels of Periodontal Attachment. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2013, 51, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, F.; Bieling, K.; Latz, T.; Nuesry, E.; Becker, J. Healing of Intrabony Peri-Implantitis Defects Following Application of a Nanocrystalline Hydroxyapatite (Ostim) or a Bovine-Derived Xenograft (Bio-Oss) in Combination with a Collagen Membrane (Bio-Gide). A Case Series. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2006, 33, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).