Recent Progress on Ge/SiGe Quantum Well Optical Modulators, Detectors, and Emitters for Optical Interconnects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Ge/SiGe Quantum Well Optical Modulators

3. Ge/SiGe Quantum Well Optical Detection and Emission

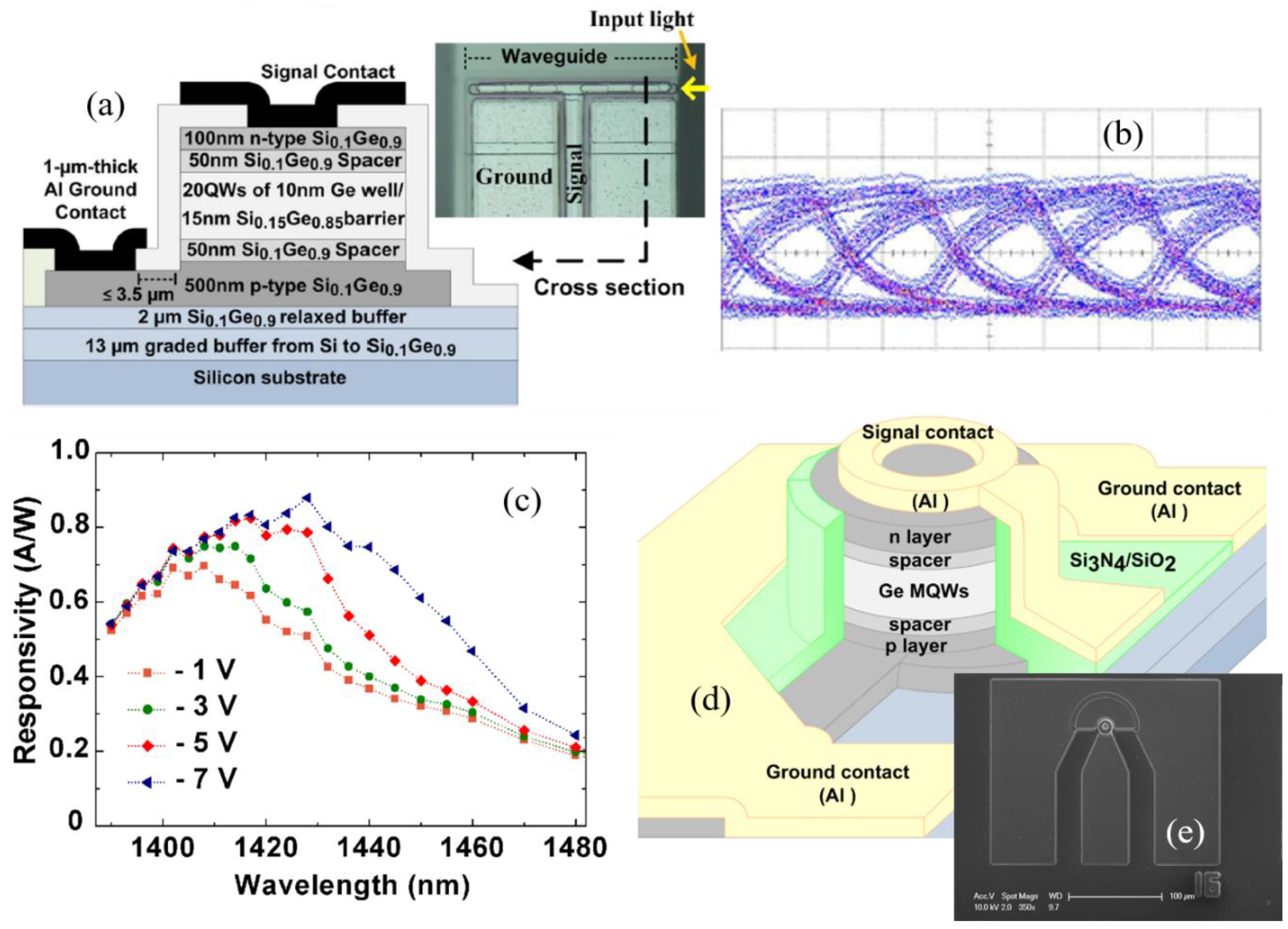

3.1. Optical Detection from Ge/SiGe MQWs

3.2. Optical Emission from Ge/SiGe MQWs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wada, K.; Kimerling, L.C. Photonics and Electronics with Germanium; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.A.; Rationale, B. Challenges for Optical Interconnects to Electronic Chips. Proc. IEEE 2000, 88, 728–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Camacho-Aguilera, R.; Bessette, J.T.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Cai, Y.; Kimerling, L.C.; Michel, J. Ge-on-Si optoelectronics. Thin Solid Films 2012, 520, 3354–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J. Emerging technologies in Si active photonics. J. Semicond. 2018, 39, 061001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.A.B. Device requirements for optical interconnects to silicon chips. Proc. IEEE 2009, 97, 1166–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Beals, M.; Pomerene, A.; Bernardis, S.; Sun, R.; Cheng, J.; Kimerling, L.C.; Michel, J. Waveguide-integrated, ultralow-energy GeSi electro-absorption modulators. Nat. Photonics 2008, 2, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, S.; Xia, F.; Bedell, S.W.; Zhang, Y.; Topuria, T.; Rice, P.M.; Vlasov, Y.A. CMOS-integrated high-speed MSM germanium waveguide photodetector. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 4986–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, N.-N.; Feng, D.; Liao, S.; Wang, X.; Dong, P.; Liang, H.; Kung, C.-C.; Qian, W.; Fong, J.; Shafiiha, R.; et al. 30 GHz Ge electro-absorption modulator integrated with 3 μm silicon-on-insulator waveguide. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 7062–7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Kersauson, M.M.; El Kurdi, D.S.; Checoury, X.; Fishman, G.; Sauvage, S.; Jakomin, R.; Beaudoin, G.; Sagnes, I.; Boucaud, P. Optical gain in single tensile-strained germanium photonic wire. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 17925–17934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivien, L.; Polzer, A.; Marris-Morini, D.; Osmond, J.; Hartmann, J.M.; Crozat, P.; Cassan, E.; Kopp, C.; Zimmermann, H.; Fédéli, J.M. Zero-bias 40 Gbit/s germanium waveguide photodetector on silicon. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho-Aguilera, R.E.; Cai, Y.; Patel, N.; Bessette, J.T.; Romagnoli, M.; Kimerling, L.C.; Michel, J. An electrically pumped germanium laser. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 11316–11320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, A.; Verheyen, P.; Loo, R.; De Wolf, I.; Pantouvaki, M.; Lepage, G.; Balakrishnan, S.; Vanherle, W.; Absil, P.; Van Campenhout, J. 50 Gb/s C-band GeSi Waveguide Electro-Absorption Modulator. In Proceedings of the Optical Fiber Communication Conference (OFC), Anaheim, CA, USA, 20–24 March 2016; p. Tu3D.7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Galili, M.; Verheyen, P.; De Heyn, P.; Lepage, G.; De Coster, J.; Balakrishnan, S.; Absil, P.; Oxenlowe, L.; Van Campenhout, J.; et al. 100-Gbps RZ data reception in 67-GHz Si-contacted germanium waveguide pin photodetectors. J. Lightwave Technol. 2017, 35, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, M.; Pollak, F.H. Energy-band structure of germanium and silicon: The k·p method. Phys. Rev. 1966, 142, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, G.G.; McLean, T.P.; Quarrington, J.E.; Roberts, V. Fine structure in the absorption-edge spectrum of Ge. Phys. Rev. 1957, 108, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, W.C.; Newman, R. Intrinsic Optical Absorption in Single-Crystal Germanium and Silicon at 77 K and 300 K. Phys. Rev. 1955, 99, 1151–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.A.B.; Chemla, D.S.; Damen, T.C.; Gossard, A.C.; Wiegmann, W.; Wood, T.H.; Burrus, C.A. Band-edge electroabsorption in quantum well structures: The quantum-confined Stark effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984, 53, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.K.; Ge, Y.; Ren, S.; Roth, J.E.; Kamins, T.I.; Miller, D.A.B.; Harris, J.S. Strong quantum-confined Stark effect in a germanium quantum-well structures on silicon. Nature 2005, 437, 1334–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.K.; Ge, Y.; Ren, S.; Roth, J.E.; Kamins, T.I.; Miller, D.A.B.; Harris, J.S., Jr. Quantum-confined stark effect in Ge/SiGe quantum wells on Si for optical modulators. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2006, 12, 1503–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaevitz, R.K.; Roth, J.E.; Member, R.S.; Fidaner, O.; Miller, D.A.B. Material Properties of Si-GeGe Quantum Wells. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2008, 14, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgilio, M.; Grosso, G. Quantum-confined Stark effect in Ge/SiGe quantum wells: A tight-binding description. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 165315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.J. 8-band k.p modelling of the quantum confined Stark effect in Ge quantum wells on Si substrates. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 155323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, L.; Ikonic, Z.; Valavanis, A.; Cooper, J.; Kelsall, R. Design of Ge-SiGe quantum-confined Stark effect electroabsorption heterostructures for CMOS compatible photonics. J. Lightwave Technol. 2010, 28, 3273–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, Y.; De Seta, M.; Capellini, G.; Evangelisti, F.; Ortolani, M.; Virgilio, M.; Grosso, G.; Pizzi, G.; Calvani, P.; Lupi, S.; et al. Near- and far-infrared absorption and electronic structure of Ge-SiGe multiple quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 205317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-H.; Li, Y.-S. Direct-gap exciton and optical absorption in the Ge/SiGe quantum well system. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-H.; Li, Y.-S. Variational calculation for the direct-gap exciton in the Ge quantum well systems. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 245328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaevitz, R.K.; Edwards, E.H.; Roth, J.E.; Fei, E.T.; Rong, Y.; Wahl, P.; Kamins, T.I.; Harris, J.S.; Miller, D.A.B. Simple electroabsorption calculator for designing 1310 nm and 1550 nm modulators using germanium quantum wells. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2012, 48, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujino, S.; Sigg, H.; Mussler, G.; Chrastina, D.; von Känel, H. Photocurrent and transmission spectroscopy of direct-gap interband transitions in Ge/SiGe quantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 262119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, M.; Grilli, E.; Guzzi, M.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; von Känel, H.; Sigg, H. Direct-gap related optical transitions in Ge/SiGe quantum wells with Ge-rich barriers. Physica E 2009, 41, 972–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Isella, G.; Chrastina, D.; Le Roux, X.; Gatti, E.; Edmond, S.; Osmond, J.; Cassan, E.; Vivien, L. Quantum-confined Stark effect measurements in Ge/SiGe quantum-well structures. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 2913–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isella, G.; Chrastina, D.; Rössner, B.; Hackbarth, T.; Herzog, H.-J.; König, U.; von Känel, H. Low-energy plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition for strained Si and Ge heterostructures and devices. Solid-State Electron. 2004, 48, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D.; Zilkie, A.; Bowers, J.E.; Komljenovic, T.; Reed, G.T.; Vivien, L.; Marris-Morini, D.; Cassan, E.; Virot, L.; Fédéli, J.-M.; et al. Roadmap on silicon photonics. J. Opt. 2016, 18, 073003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.T.; Mashanovich, G.; Gardes, F.Y.; Thomson, D.J. Silicon optical modulators. Nat. Photon. 2010, 4, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yako, M.; Ju, K.; Kawai, N.; Chaisakul, P.; Tsuchizawa, T.; Hikita, M.; Yamada, K.; Ishikawa, Y.; Wada, K. A new material platform of Si photonics for implementing architecture of dense wavelength division multiplexing on Si bulk wafer. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2017, 18, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kekatpure, R.D.; Lentine, A. The suitability of SiGe multiple quantum well modulators for short reach DWDM optical interconnects. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 5318–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, J.E.; Fidaner, O.; Schaevitz, R.K.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Kamins, T.I.; Harris, J.S.; Miller, D.A.B. Optical modulator on silicon employing germanium quantum wells. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 5851–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, J.E.; Fidaner, O.; Englund, E.E.; Schaevitz, R.K.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Helman, N.C.; Kamins, T.I.; Harris, J.S.; Miller, D.A.B. C-band side-entry Ge quantum well electroabsorption modulator on SOI operating at 1 volt swing. Electron. Lett. 2008, 44, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, S.M.; Ng, K.K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices, 3rd ed.; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, E.H.; Audet, R.M.; Fei, E.T.; Claussen, S.A.; Schaevitz, R.K.; Tasyurek, E.; Rong, Y.; Kamins, T.I.; Harris, J.S.; Miller, D.A.B. Ge/SiGe asymmetric Fabry-Perot quantum well electroabsorption modulators. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 29164–29173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audet, R.M.; Edwards, E.H.; Balram, K.C.; Claussen, S.A.; Schaevitz, R.K.; Tasyurek, E.; Rong, Y.; Fei, E.I.; Kamins, T.I.; Harris, J.S.; et al. Surface-normal ge/sige asymmetric fabry-perot optical modulators fabricated on silicon substrates. J. Lightwave Technol. 2013, 31, 3995–4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.-P.; Kuo, Y.-H. Design of vertical Ge quantum well asymmetric Fabry-Perot modulator without DBR. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 23576–23583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, Y.; Ge, Y.; Huo, Y.; Fiorentino, M.; Tan, M.R.T.; Kamins, T.I.; Ochalski, T.J.; Huyet, G.; Harris, J.S., Jr. Quantum-confined Stark effect in Ge/SiGe quantum wells on Si. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2010, 16, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Isella, G.; Chrastina, D.; Le Roux, X.; Edmond, S.; Coudevylle, J.-R.; Cassan, E.; Vivien, L. Polarization dependence of quantum-confined Stark effect in Ge/SiGe quantum well planar waveguides. Opt. Lett. 2011, 36, 1794–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgilio, M.; Bonfanti, M.; Chrastina, D.; Neels, A.; Isella, G.; Grilli, E.; Guzzi, M.; Grosso, G.; Sigg, H.; von Känel, H. Polarization-dependent absorption in Ge/SiGe multiple quantum wells: Theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 075323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Rouifed, M.S.; Frigerio, J.; Isella, G.; Chrastina, D.; Coudevylle, J.R.; Le Roux, X.; Edmond, S.; Bouville, D.; et al. Strong quantum-confined Stark effect from light hole related direct-gap transitions in Ge quantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 191107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Rouifed, M.-S.; Isella, G.; Chrastina, D.; Frigerio, J.; Le Roux, X.; Edmond, S.; Coudevylle, J.-R.; Vivien, L. 23 GHz Ge/SiGe multiple quantum well electro-absorption modulator. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 3219–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.-H.; Chen, H.-W.; Bowers, J.E. High speed hybrid silicon evanescent electroabsorption modulator. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 9936–9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaevitz, R.K.; Ly-Gagnon, D.S.; Roth, J.E.; Edwards, E.H.; Miller, D.A.B. Indirect absorption in germanium quantum wells. AIP Adv. 2011, 1, 032164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ahn, D. Effect of indirect interband absorption in Ge/SiGe quantum wells. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 083119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.H.; Lever, L.; Fei, E.T.; Kamins, T.I.; Ikonic, Z.; Harris, J.S.; Kelsall, R.W.; Miller, D.A.B. Low-voltage broad-band electroabsorption from thin Ge/SiGe quantum wells epitaxially grown on silicon. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lever, L.; Hu, Y.; Myronov, M.; Liu, X.; Owens, N.; Gardes, F.Y.; Marko, I.P.; Sweeney, S.J.; Ikonić, Z.; Leadley, D.R.; et al. Modulation of the absorption coefficient at 1.3 μm in Ge/SiGe multiple quantum well heterostructures on silicon. Opt. Lett. 2011, 36, 4158–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouifed, M.S.; Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Frigerio, J.; Isella, G.; Chrastina, D.; Edmond, S.; Le Roux, X.; Coudevylle, J.-R.; Vivien, L. Quantum-confined Stark effect at 1.3 μm in Ge/Si0.35Ge0.65 quantum-well structure. Opt. Lett. 2012, 37, 3960–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouifed, M.S.; Marris-Morini, D.; Chaisakul, P.; Frigerio, J.; Isella, G.; Chrastina, D.; Edmond, S.; Le Roux, X.; Coudevylle, J.R.; Bouville, D.; et al. Advances Toward Ge/SiGe Quantum-Well Waveguide Modulators at 1.3 μm. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2014, 20, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Rouifed, M.-S.; Frigerio, J.; Chrastina, D.; Coudevylle, J.-R.; Le Roux, X.; Edmond, S.; Isella, G.; Vivien, L. Recent progress in GeSi electro-absorption modulators. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2014, 15, 014601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaisakul, P.; Frigerio, J.; Marris-Morini, D.; Vakarin, V.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; Vivien, L. O-band quantum-confined Stark effect optical modulator from Ge/SiGe quantum wells by well thickness tuning. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 193103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, J. Design of low bias voltage Ge/SiGe multiple quantum wells electro-absorption modulator at 1550 nm. AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 035317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, D.C.S.; Gallacher, K.; Rhead, S.; Myronov, M.; Leadley, D.R.; Paul, D.J. Ge/SiGe quantum confined Stark effect electro-absorption modulation with low voltage swing at λ = 1550 nm. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 19284–19292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, G.-E.; Chang, C.-O. Tensile-Strained Ge/SiGeSn Quantum Wells for Polarization-Insensitive Electro-Absorption Waveguide Modulators. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2012, 48, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Sun, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Y. Design and analysis of electro-absorption modulators with uniaxially stressed Ge/SiGe multiple quantum wells. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 10874–10884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iseri, Y.; Yamada, H.; Goda, Y.; Arakawa, T.; Tada, K.; Haneji, N. Analysis of electrorefractive index change in Ge/SiGe coupled quantum well for low-voltage silicon-based optical modulators. Phys. E 2011, 43, 1433–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, J.; Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Cecchi, S.; Rouifed, M.-S.; Isella, G.; Vivien, L. Electro-Refractive Effect in Ge/SiGe Multiple Quantum Wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 061102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, J.; Vakarin, V.; Chaisakul, P.; Ferretto, M.; Chrastina, D.; Le Roux, X.; Vivien, L.; Isella, G.; Marris-Morini, D. Giant electro-optic effect in Ge/SiGe coupled quantum wells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Gao, J. Theoretical analysis of electro-refractive index variation in asymmetric Ge/SiGe coupled quantum wells. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 30032–30042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lever, L.; Ikonić, Z.; Kelsall, R.W. Adiabatic mode coupling between SiGe photonic devices and SOI waveguides. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 29500–29506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; Kamins, T.I.; Miller, D.A.B. Thin dielectric spacer for the monolithic integration of bulk germanium or germanium quantum wells with silicon-on-insulator waveguides. IEEE Photonics J. 2011, 3, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Rong, Y.; Claussen, S.A.; Schaevitz, R.K.; Kamins, T.I.; Harris, J.S.; Miller, D.A.B. Ge/SiGe quantum well waveguide modulator monolithically integrated with SOI waveguides. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2012, 24, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claussen, S.A.; Balram, K.C.; Fei, E.T.; Kamins, T.I.; Harris, J.S.; Miller, D.A.B. Selective area growth of germanium and germanium/silicon-germanium quantum wells in silicon waveguides for on-chip optical interconnect applications. Opt. Mater. Express 2012, 2, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Frigerio, J.; Chrastina, D.; Rouifed, M.-S.; Cecchi, S.; Crozat, P.; Isella, G.; Vivien, L. Integrated germanium optical interconnects on silicon substrates. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Sun, J.; Gao, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, Y. Design of compact and efficient polarization-insensitive taper coupler for SiGe photonic integration. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 23784–23797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, K.; Lu, C.-Y.; Chen, X.; Fei, E.; Xue, M.; Claussen, S.; Morea, M.; Chen, Y.; Dutt, R.; Huo, Y.; et al. Germanium Quantum Well QCSE Waveguide Modulator with Tapered Coupling in Distributed Modulator–Detector System. J. Lightwave Technol. 2017, 35, 4629–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.A.; Porret, C.; Vissers, E.; Geiregat, P.; Van Thourhout, D.; Loo, R.; Pantouvaki, M.; Van Campenhout, J. High-contrast quantum-confined Stark effect in Ge/SiGe quantum well stacks on Si with ultra-thin buffer layers. In Proceedings of the Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics/Pacific Rim 2018, Hong Kong, China, 29 July–3 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kamins, T.I. Pattern sensitivity of selective Si1−xGex chemical vapor deposition: Pressure dependence. J. Appl. Phys. 1993, 74, 5799–5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Rong, Y.; Kamins, T.I.; Harris, J.S.; Miller, D.A.B. Selective epitaxial growth of Ge/Si0.15Ge0.85 quantum wells on Si substrate using reduced pressure chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 151108. [Google Scholar]

- Fidaner, O.; Okyay, A.K.; Roth, J.E.; Schaevitz, R.K.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Saraswat, K.C.; Harris, J.S.; Miller, D.A.B. Ge-SiGe quantum-well waveguide photodetectors on silicon for the near-infrared. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2007, 19, 1631–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Isella, G.; Chrastina, D.; Rouifed, M.-S.; Le Roux, X.; Edmond, S.; Cassan, E.; Coudevylle, J.-R.; Vivien, L. 10-Gb/s Ge/SiGe Multiple Quantum-Well Waveguide Photodetector. IEEE Photonic Technol. Lett. 2011, 23, 1430–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.A.B. Optical interconnects to electronic chips. Appl. Opt. 2010, 49, F59–F70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Isella, G.; Chrastina, D.; Le Roux, X.; Edmond, S.; Cassan, E.; Coudevylle, J.-R.; Vivien, L. Ge/SiGe multiple quantum well photodiode with 30 GHz bandwidth. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 131112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgioni, A.; Gatti, E.; Grilli, E.; Chernikov, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; Guzzi, M. Photoluminescence decay of direct and indirect transitions in Ge/SiGe multiple quantum wells. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 013501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claussen, S.A.; Tasyurek, E.; Roth, J.E.; Miller, D.A. Measurement and modeling of ultrafast carrier dynamics and transport in germanium/silicon-germanium quantum wells. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 25596–25607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onaran, E.; Onbasli, M.C.; Yesilyurt, A.; Yu, H.Y.; Nayfeh, A.M.; Okyay, A.K. Silicon-Germanium multi-quantum well photodetectors in the near infrared. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 7608–7615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, G.-E.; Chen, S.-W.; Cheng, H.H. Tensile-strained Ge/SiGe quantum-well photodetectors on silicon substrates with extended infrared response. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 17562–17571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Kimerling, L.C.; Michel, J. Direct-gap optical gain of Ge on Si at room temperature. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 1738–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, J.R.; Nilsson, N.G. Physics of Semiconductors: Proceedings of the VIIth International Conference; Dunod: Paris, France, 1964; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Pan, D.; Wang, X.; Kimerling, L.C.; Koch, T.L.; Michel, J. Tensile-strained, n-type Ge as a gain medium for monolithic laser integration on Si. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 11272–11277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Camacho-Aguilera, R.; Kimerling, L.C.; Michel, J. Ge-on-Si laser operating at room temperature. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 679–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, L.; Friedli, P.; Neuenschwander, S.; Sigg, H.; Cecchi, S.; Isa, F.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; Fedoryshyn, Y.; Faist, J. Direct-gap gain and optical absorption in Germanium correlated to the density of photoexcited carriers, doping, and strain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 057402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iga, K.; Koyama, F.; Konoshita, S. Surface emitting semiconductor lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1988, 24, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, J.L.; Scherer, A.; McCall, S.L.; Lee, Y.H.; Walker, S.; Harbison, J.P.; Florez, L.T. Low-threshold electrically pumped vertical-cavity surface-emitting microlasers. Electron. Lett. 1989, 25, 1123–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, P.; Borchert, B.; Stegmuller, B. Improved behavior of monolithically integrated laser/modulator by modified identical active layer structure. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 1997, 9, 1561–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, W.; Arai, M.; Yamanaka, T.; Fujiwara, N.; Fujisawa, T.; Tadokoro, T.; Tsuzuki, K.; Kondo, Y.; Kano, F. Design and Fabrication of 10-/40-Gb/s, Uncooled Electroabsorption Modulator Integrated DFB Laser with Butt-Joint Structure. J. Lightwave Technol. 2010, 28, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Smith, A.D.; O’Reilly, E.P.; Silver, M.; Briggs, A.T.R.; Fice, M.J.; Adams, A.R.; Greene, P.D.; Scarrott, K.; Vranic, A. The influence of tensile strain on differential gain and auger recombination in 1.5-μm multiple-quantum-well lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1998, 34, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, C.; Köster, N.S.; Chatterjee, S.; Sigg, H.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; von Känel, H.; Schäfer, M.; Kira, M.; Koch, S.W. Ultrafast nonlinear optical response of photoexcited Ge/SiGe quantum wells: Evidence for a femtosecond transient population inversion. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 201306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, N.S.; Lange, C.; Kolata, K.; Chatterjee, S.; Schäfer, M.; Kira, M.; Koch, S.W.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; von Känel, H.; et al. Ultrafast transient gain in Ge/SiGe quantum wells. Phys. Status Solidi C 2011, 8, 1109–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, E.; Grilli, E.; Guzzi, M.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; Chernikov, A.; Bornwasser, V.; Köster, N.; Woscholski, R.; Chatterjee, S. Photoluminescence and ultrafast inter-subband relaxation in Ge/SiGe multiple quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 245319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, E.; Grilli, E.; Guzzi, M.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; von Känel, H. Room temperature photoluminescence of Ge multiple quantum wells with Ge-rich barriers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 031106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.H.; Dumcenco, D.; Huang, Y.S.; Hsu, H.P.; Lai, C.H.; Lin, T.Y.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; Gatti, E.; Tiong, K.K. Above-room-temperature photoluminescence from a strain-compensated Ge/Si0.15Ge0.85 multiple-quantum-well structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 141905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Cheng, B.; Xue, C.; Zhang, G.; Su, S.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, Q. Room-temperature direct-bandgap photoluminescence from strain-compensated Ge/SiGe multiple quantum wells on silicon. Chin. Phys. B 2012, 21, 017805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisakul, P.; Marris-Morini, D.; Isella, G.; Chrastina, D.; Izard, N.; Le Roux, X.; Edmond, S.; Coudevylle, J.-R.; Vivien, L. Room temperature direct gap electroluminescence from Ge/Si0.15Ge0.85 multiple quantum well waveguide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 141106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, W.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Xue, C.; Li, C.; Zuo, Y.; Chenga, B.; Wang, Q. Room temperature direct-bandgap electroluminescence from n-type strain-compensated Ge/SiGe multiple quantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 231108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastard, G. Wave Mechanics Applied to Semiconductor Heterostructures; Halstead Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Han, Z.; Wang, X.; Camacho-Aguilera, R.E.; Kimerling, L.C.; Michel, J.; Liu, J. Analysis of Threshold Current Behavior for Bulk and Quantum-Well Germanium Laser Structures. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2013, 19, 1901009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Lai, H.; Chen, S.; Ding, W.; Cheng, B.; Yu, Y. Room temperature photoluminescence of tensile-strained Ge/Si0.13Ge0.87 quantum wells grown on silicon-based germanium virtual substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 141902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Lai, H.; Chen, S. Quantum-confined direct band transitions in tensile strained Ge/SiGe quantum wells on silicon substrates. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 115207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, L.; Imbert, F.; Sigg, H.; Süess, M.; Müller, E.; Virgilio, M.; Pizzi, G.; Rossbach, P.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G. Quantum-confined direct-gap transitions in tensile-strained Ge/SiGe multiple quantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 031907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süess, M.J.; Carroll, L.; Sigg, H.; Diaz, A.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; Müller, E.; Spolenak, R. Tensile strained Ge quantum wells on Si substrate: Post-growth annealing versus low temperature re-growth. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2012, 177, 696–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fenrich, C.S.; Xue, M.; Kao, M.-Y.; Zang, K.; Lu, C.-Y.; Fei, E.T.; Chen, Y.; Huo, Y.; Kamins, T.I.; et al. Tensile-strained Ge/SiGe multiple quantum well microdisks. Photonics Res. 2017, 5, B7–B14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallacher, K.; Velha, P.; Paul, D.J.; Cecchi, S.; Frigerio, J.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G. 1.55 μm direct bandgap electroluminescence from strained n-Ge quantum wells grown on Si substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 211101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, W.; Xue, C.; Cheng, B. Direct-bandgap electroluminescence from tensile-strained Ge/SiGe multiple quantum wells at room temperature. Chin. Phys. B 2014, 23, 116103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Chen, N.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Z.; Huang, W.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Chen, S.; Li, C. Room Temperature Electroluminescence from Tensile-Strained Ge/Si0.13Ge0.87 Multiple Quantum Wells on a Ge Virtual Substrate. Materials 2016, 9, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Sun, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, R. Analysis of threshold current of uniaxially tensile stressed bulk Ge and Ge/SiGe quantum well lasers. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 26714–26727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ge QWs Structures | Buffer and Substrate | Extinction Ratio (ER) | Insertion Loss (IL) at Operating Point | ER/IL | Voltage Swing (VPP) and Electric Field Swing (V/cm) | Footprint of Active Region (Width × Length in µm2) | 3-dB Modulation Bandwidth/Data Rate | Optical Bandwidth ER/IL >1 ER/IL ≥2 | Reported Dynamic Energy Dissipation 1/4CVpp2 (fJ/bit) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roth et al. [36] Side entry (Transmission) | 40 periods of 15.5-nm Ge/33-nm Si0.16 Ge0.84 | 1-μm Si0.1Ge0.9 buffer on bulk Si | 7.3 dB (1457 nm) | - | - | 10 (0–10 V) ~4.8 × 104 V/cm | 450 × 450 | - | - | - |

| Roth et al. [37] Side entry (Transmission) | 10 periods of 15.5-nm Ge/33-nm Si0.16 Ge0.84 | 900-nm Si0.1Ge0.9 buffer on SOI | 3 dB (1541 nm) | - | - | 1 (3.6–4.6 V) ~1.5 × 104 V/cm | 225 × 625 | - | - | - |

| Edwards et al. [39] Vertical incidence Fabry-Perot (Transmission) | 15 periods of 10-nm Ge/17-nm Si0.19Ge0.81 | 800-nm Si0.12Ge0.88 Buffer on Pyrex wafer | 3.5 dB 2 dB (1429 nm) | 3.7 dB 4.4 dB | 0.95 0.45 | 3 (0.5–3.5 V) 1.5 (1–2.5 V) ~5.2 × 104 ~2.6 × 104 V/cm | πx302 (radius of 30 µm) | 3.5 GHz/ 2 Gb/s | - | - |

| Audet et al. [40] vertical incidence Fabry-Perot (Transmission) | 10 periods of 10-nm Ge/15.5-nm Si0.15Ge0.85 | 500-nm Si0.1Ge0.9 buffer on bulk Si | 6.7 dB 9.6 dB 10 dB (~1471 nm) | 4.1 dB 1.8 dB 1.3 dB | 1.6 5.3 7.7 | 1 (5.5–6.5 V) 2 (4.5–6.5 V) 3 (3.5–6.5 V) ~2.2 × 104 ~4.4 × 104 ~6.6 × 104 V/cm | πx202 (radius of 20 µm) | 4 GHz | ~1 nm ~2 nm ~2 nm - ~1 nm ~1 nm | 54 |

| Chaisakul et al. [43] Planar waveguide (Transmission) | 20 periods of 10-nm Ge/15-nm Si0.15Ge0.85 | 13-μm graded buffer from Si to Si0.1Ge0.9 on bulk Si | 10 dB (1428 nm) | 4.2 dB | 2.3 | 6 (0–6 V) ~6.6 × 104 V/cm | 100 × 64 | - | ~25 nm (1420 to 1445 nm) ~14 nm (1425 to1439 nm) | - |

| Chaisakul et al. [45] Planar waveguide (Photocurrent) | 10 periods of 10-nm Ge/15-nm Si0.15Ge0.85 | 13-μm graded buffer from Si to Si0.1Ge0.9 on bulk Si | 5 dB (1350 nm) | 3.3 dB | 1.5 | 4 (0–4 V) ~11 × 104 V/cm | 100 × 38 | - | ~10 nm (1345 to1355 nm) | - |

| Chaisakul et al. [46] Waveguide (Transmission) | 20 periods of 10-nm Ge/15-nm Si0.15Ge0.85 | 13-μm graded buffer from Si to Si0.1Ge0.9 on bulk Si | 9 dB 11 dB | 12 dB 7.5 dB | 0.75 1.5 | 1 (3–4 V) 5 (0–5 V) ~1.5 × 104 ~7.5 × 104 V/cm | 3 × 90 | 23 GHz | - ~11 nm (1435 to 1446 nm) | 16 |

| Rouifed et al. [53] Waveguide (Transmission) | 20 periods of 8-nm Ge/12-nm Si0.35Ge0.65 | 11-μm graded buffer from Si to Si0.21Ge0.79 on bulk Si | 4 dB 5 dB (~1295 nm) | 4 dB 4 dB | 1 1.25 | 2 (4–6 V) 3 (4–7 V) ~3.3 × 104 ~5.0 × 104 V/cm | 3 × 50 | - | - ~9 nm (1293 to 1302 nm) | - |

| Chaisakul et al. [55] SiGe-waveguide integrated (Transmission) | 20 periods of 6.5-nm Ge/10-nm Si0.15Ge0.85 | 11-μm graded buffer from Si to Si0.2Ge0.8 on bulk Si | 8 dB (1345 nm) | 5 dB | 1.6 | 6 (0–6 V) ~11 × 104 V/cm | 4 × 100 | - | ~20 nm (1334 to 1354 nm) | - |

| Ren et al. [66] SOI-waveguide integrated (Transmission) | 15 periods of 12-nm Ge/20-nm Si0.15Ge0.85 | ~1-μm Si0.1Ge0.9 buffer on SOI | 3 dB (1460 nm) | 15 dB | 0.2 | 1 (3.5–4.5 V) ~1.7 × 104 V/cm | 0.8 × 10 | 3.5 GHz 7 Gb/s | - | 0.75 |

| Chaisakul et al. [68] SiGe-waveguide integrated (Transmission) | 10 periods of 12-nm Ge/16-nm Si0.16Ge0.84 | 8-μm graded buffer from Si to Si0.17Ge0.83 on bulk Si | 3 dB 4 dB (~1435 nm) | 3 dB 3 dB | 1 1.3 | 2 (0–2 V) 3 (0–3 V) ~5.6 × 104 ~8.4 × 104 V/cm | 4 × 100 | 6.3 GHz | ~5 nm (1425 to 1430 nm) ~25 nm (1425 to 1450 nm) | - |

| Ge QWs Structures | Responsivity | Reasons for Low Responsivity | Dark Current Density | Reverse Bias Voltage | 3-dB Modulation Bandwidth/Data Rate | Footprint of Active Region (Width × Length in µm2) | Reported Wavelength Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fidaner et al. [74] Waveguide | 10 periods of 15-nm Ge/33-nm Si0.16 Ge0.84 | 0.17 A/W (1480 nm) | Low overlap between optical mode and QWs | 17.9 mA/cm2 | 0.5–10 V | 2.5 Gb/s | 3 × 40 | 1440–1530 nm |

| Chaisakul et al. [75] Waveguide | 20 periods of 10-nm Ge/15-nm Si0.16 Ge0.85 | 0.8 A/W (1411 nm) | - | 198 mA/cm2 | 1–3 V | 10 Gb/s | 3 × 80 | 1400–1460 nm |

| Chaisakul et al. [77] Surface-Illuminated | 20 periods of 10-nm Ge/15-nm Si0.16 Ge0.85 | 0.05 A/W (~1471 nm) | Short absorption length (surface illumination) | 214 mA/cm2 | 1–7 V | 10–30 GHz | πx62 (radius of 6 µm) | 1395–1455 nm |

| Onaran et al. [80] Surface-Illuminated | 10 periods of 10-nm Ge/20-nm Si0.10Ge0.90 | 0.01 A/W (1550 nm) | Short absorption length (surface illumination) | 10 mA/cm2 | 2–3 V | - | πx402 (radius of 40 µm) | 1300–1600 nm |

| Chaisakul et al. [68] SiGe-waveguide integrated | 10 periods of 12-nm Ge/16-nm Si0.16Ge0.84 | 0.6 A/W (1440 nm) | - | 2.5 mA/cm2 | 1–3V | 4 GHz | 4 × 100 | 1400–1520 nm |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chaisakul, P.; Vakarin, V.; Frigerio, J.; Chrastina, D.; Isella, G.; Vivien, L.; Marris-Morini, D. Recent Progress on Ge/SiGe Quantum Well Optical Modulators, Detectors, and Emitters for Optical Interconnects. Photonics 2019, 6, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics6010024

Chaisakul P, Vakarin V, Frigerio J, Chrastina D, Isella G, Vivien L, Marris-Morini D. Recent Progress on Ge/SiGe Quantum Well Optical Modulators, Detectors, and Emitters for Optical Interconnects. Photonics. 2019; 6(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics6010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaisakul, Papichaya, Vladyslav Vakarin, Jacopo Frigerio, Daniel Chrastina, Giovanni Isella, Laurent Vivien, and Delphine Marris-Morini. 2019. "Recent Progress on Ge/SiGe Quantum Well Optical Modulators, Detectors, and Emitters for Optical Interconnects" Photonics 6, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics6010024

APA StyleChaisakul, P., Vakarin, V., Frigerio, J., Chrastina, D., Isella, G., Vivien, L., & Marris-Morini, D. (2019). Recent Progress on Ge/SiGe Quantum Well Optical Modulators, Detectors, and Emitters for Optical Interconnects. Photonics, 6(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics6010024