Single Microwave Photon Detection with a Trapped Electron

Abstract

:1. Introduction

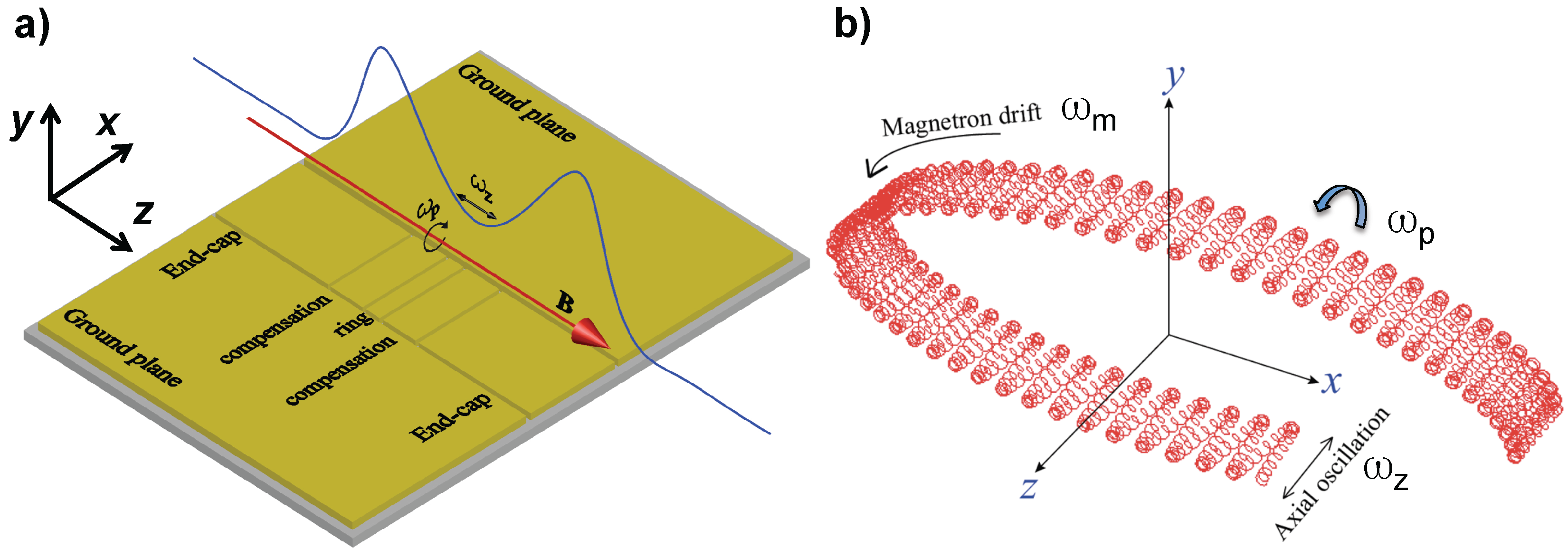

2. Basics of the Geonium Chip Planar Penning Trap

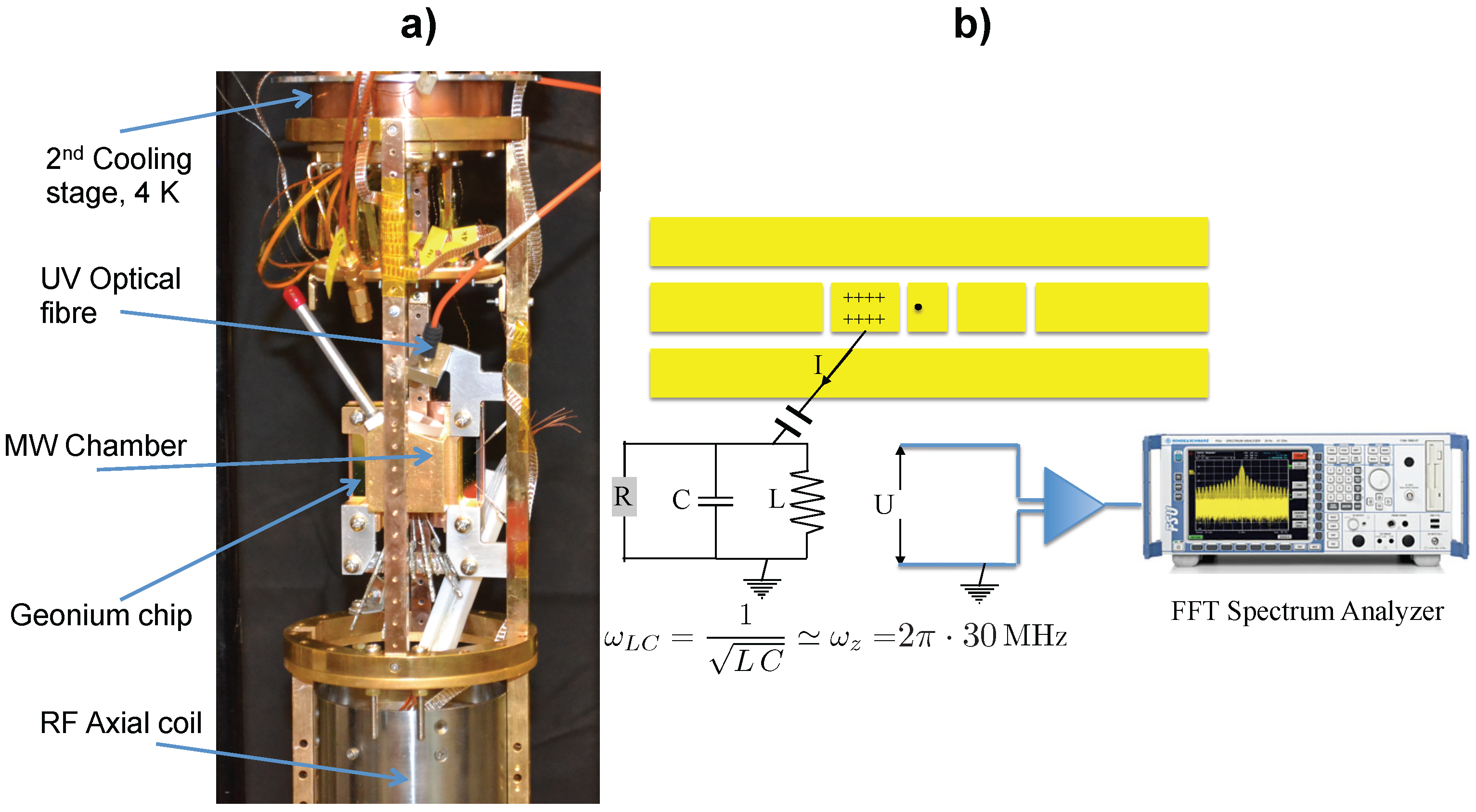

2.1. Overview of the Experimental Setup

2.2. Detection of the Trapped Electron’s Axial Motion

- The detection is non destructive: the axial frequency can be monitored continuously, without losing the trapped particle [19].

- The measurement of occurs with the axial motion being in thermal equilibrium with the LC resonator, typically at 4 K or eventually even at higher temperatures [23].

- The detection of the axial motion leaves the electron’s cyclotron quantum state unaffected [5]. Thus, while the axial motion is in thermal equilibrium with the LC resonator at 4 K, the cyclotron quantum state can be in thermal equilibrium with the 80 mK temperature provided by the ADR.

- While and the LC circuit must be resonantly coupled (see Figure 2b), the value of the trapping magnetic field, and therefore of , can be freely chosen without affecting the detection of the axial motion.

- The frequency can be measured with an accuracy of 1 Hz in around 5 s. This is the lapse required to measure an FFT spectrum of 1 Hz resolution (∼1 s each) and average it for a good signal-to-noise ratio. As explained in Section 5, such long measurement time would not allow for high quantum efficiency in MW photon detection. However, frequency variations can be determined substantially faster, by recording the phase evolution of the axial motion but without waiting for a full oscillation [26]. This will permit very rapid MW photon detection, as detailed in Section 5.

3. Detection of Microwave Photons with a Trapped Electron

3.1. Interaction of a Cyclotron Quantum Harmonic Oscillator with an Itinerant Microwave

3.2. Dynamics of Two Coupled Quantum Harmonic Oscillators

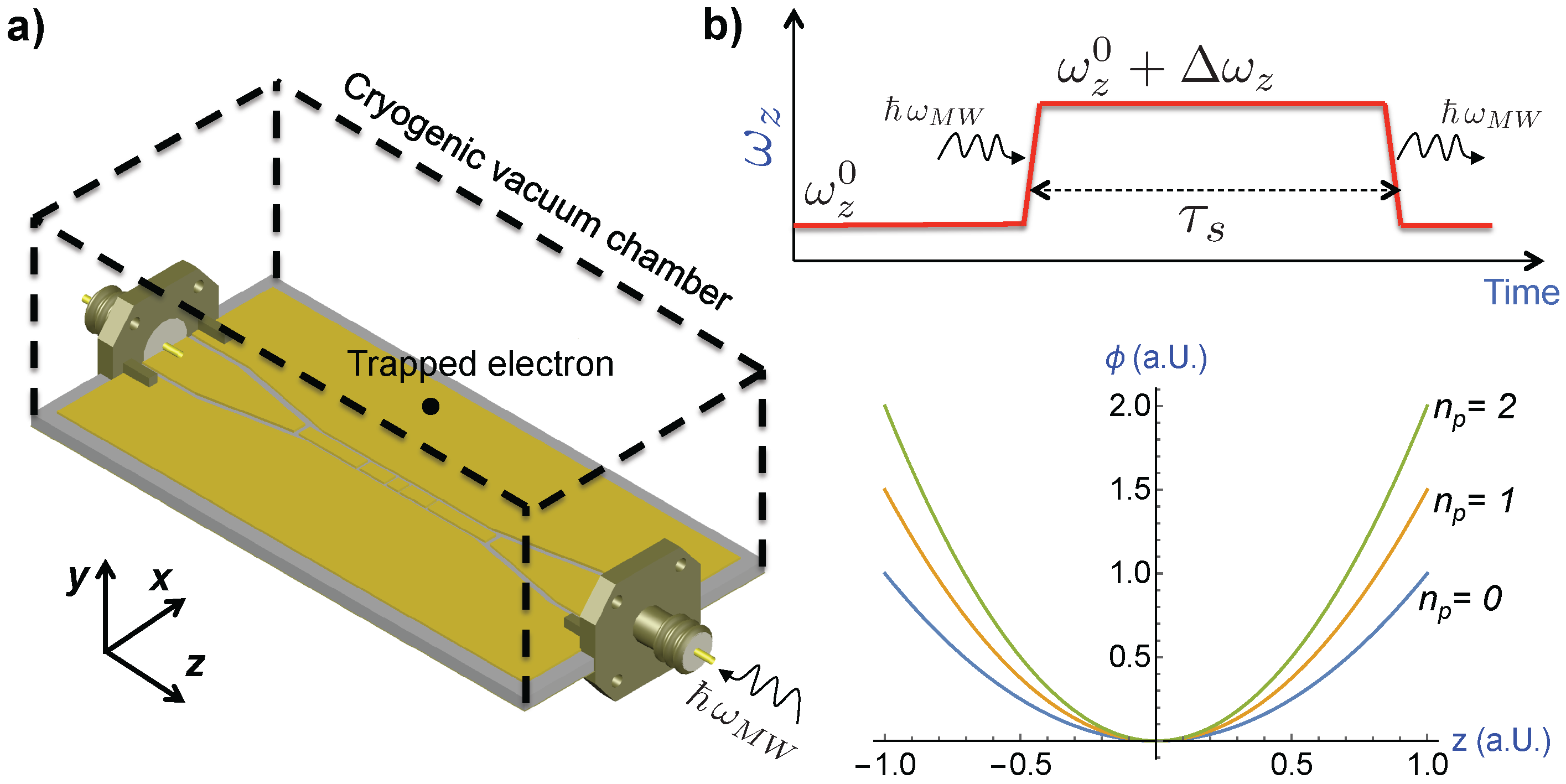

3.3. Principle of Microwave Photon Detection: The Continuous Stern-Gerlach Effect

3.4. Generation of a Magnetic Bottle in the Geonium Chip

3.5. Quantum Non Demolition Photon Detection

4. Quantum Efficiency of MW Photon Detection by a Single Trapped Electron

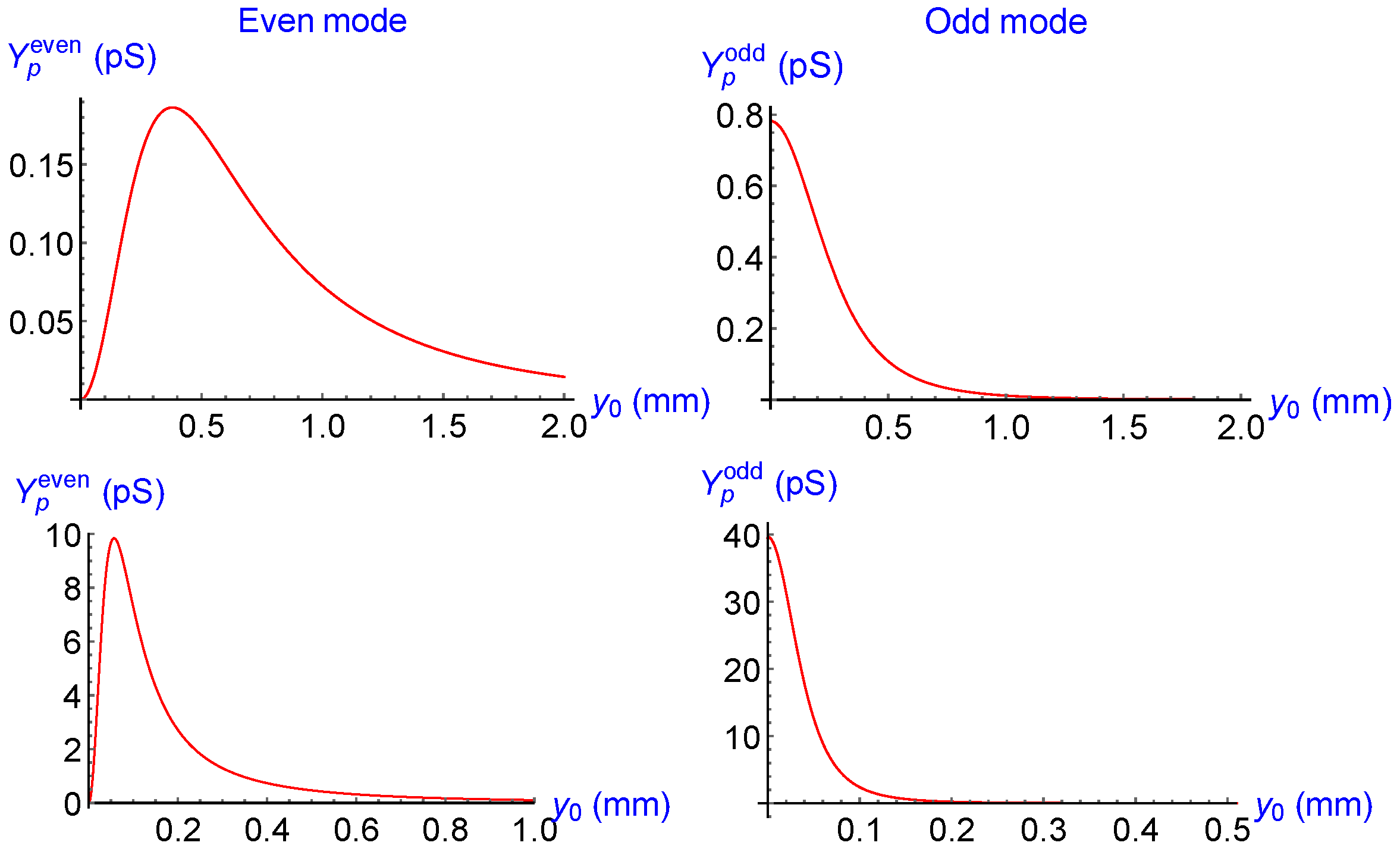

4.1. Electric Field Strength of a Single Itinerant Photon Propagating along a CPW Transmission-Line

4.2. Probability of MW Photon Absorption by the Quantum Cyclotron Oscillator

Characteristic Admittance of the Trapped Electron

4.3. Internal Quantum Efficiency of Microwave Photon Detection

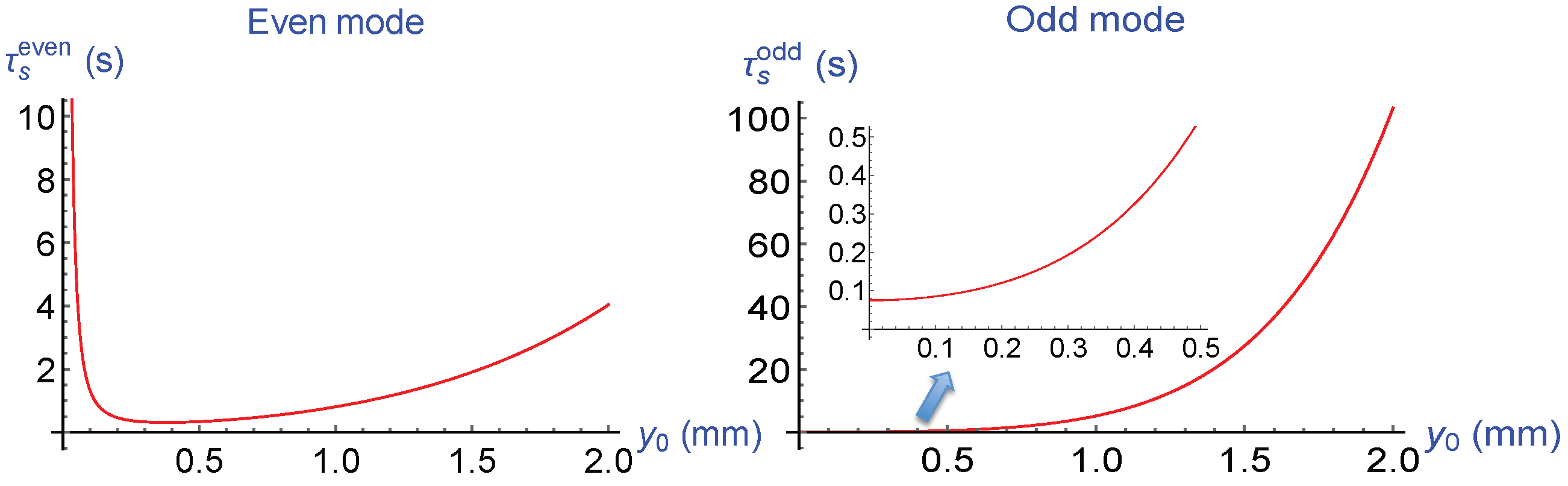

5. Speed of Quantum Jump Detection versus Cyclotron Radiative Lifetime

5.1. Quantum Cyclotron Radiative Lifetime in a CPW Transmission-Line

5.2. Measurement Time of

6. Comparison with Other Single Microwave Photon Detectors

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| ADR | Adiabatic Demagnetisation Refrigerator |

| QND | Quantum Non Demolition |

| MW | Microwave |

| EM | Electromagnetic |

| CPW | Coplanar-Waveguide |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| EDM | Electric Dipole Moment |

| CPB | Cooper Pair Box |

References

- Manninen, A.J.; Kemppinen, A.; Lehtinen, J.; Mykkänen, E.; Amato, G.; Enrico, E.; Lacquaniti, V.; Kataoka, M.; Lindström, T.; Dolata, R.; et al. Towards measurement and control of single-photon microwave radiation on chip. In Proceedings of the 2015 1st URSI Atlantic Radio Science Conference (URSI AT-RASC), Gran Canaria, Spain, 16–24 May 2015; p. 1.

- Romero, G.; García-Ripoll, J.J.; Solano, E. Microwave Photon Detector in Circuit QED. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 173602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peropadre, B.; Romero, G.; Johansson, G.; Wilson, C.M.; Solano, E.; García-Ripoll, J.J. Approaching perfect microwave photodetection in circuit QED. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 063834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyamoorthy, S.R.; Stace, T.M.; Johansson, G. Detecting itinerant single microwave photons. Comptes Rendus Physique 2016, 17, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peil, S.; Gabrielse, G. Observing the Quantum Limit of an Electron Cyclotron: QND Measurements of Quantum Jumps between Fock States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramicoli, G.; Marzoli, I.; Tombesi, P. Scalable quantum processor with trapped electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 017901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaramicoli, G.; Marzoli, I.; Tombesi, P. Trapped electrons in vacuum for a scalable quantum processor. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 70, 032301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamata, L.; Porras, D.; Cirac, J.I.; Goldman, J.; Gabrielse, G. Towards electron-electron entanglement in Penning traps. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 022301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramicoli, G.; Marzoli, I.; Tombesi, P. Quantum spin models with electrons in Penning traps. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 78, 012338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehmelt, H.G. Experiments with an isolated subatomic particle at rest. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1990, 62, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdú, J. Theory of the coplanar waveguide Penning trap. New J. Phys. 2011, 13, 113029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, J.; Verdú, J. A planar Penning trap with tunable dimensionality of the trapping potential. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2013, 356, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Donnellan, S.; Crick, D.R.; Segal, D.M. Applications of laser cooled ions in a Penning trap. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2009, 42, 154003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, F.; Hendrickson, C.; Marshall, A. High resolution mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdú, J. Ion Trap. U.S. Patent US 8,362,423 B1, 29 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Verdú, J. Ion Trap. WO Patent WO 2,013,041,615 A3, 10 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar, M. Theory of the elliptical Penning trap. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 275, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.; Hardy, G.; Hepburn, I. Performance of a fast response miniature Adiabatic Demagnetisation Refrigerator using a single crystal tungsten magnetoresistive heat switch. Cryogenics 2015, 72, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehmelt, H.G.; Walls, F.L. Bolometric technique for the rf spectroscopy of stored ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1968, 21, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rjoub, A.; Verdú, J. Electronic detection of a single particle in a coplanar-waveguide Penning trap. Appl. Phys. B 2012, 107, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferts, S.R.; Heavner, T.; Hayes, P.; Dunn, G.H. Superconducting resonator and a cryogenic GaAs field-effect transistor amplifier as a single-ion detection system. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1993, 64, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, S.; Blaum, K.; Kracke, H.; Mooser, A.; Quint, W.; Rodegheri, C.; Walz, J. A cryogenic detection system at 28.9 MHz for the non-destructive observation of a single proton at low particle energy. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 2013, 705, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, S.; Alonso, J.; Kluge, H.J.; Quint, W.; Stahl, S.; Valenzuela, T.; Verdú, J.; Vogel, M.; Werth, G. Temperature measurement of a single ion in a Penning trap. Eur. Phys. J. D 2004, 31, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdú, J.; Alonso, J.; Djekic, S.; Kluge, H.J.; Quint, W.; Stahl, S.; Valenzuela, T.; Vogel, M.; Werth, G. Determination of the g-factor of single hydrogen-like ions by mode coupling in a Penning trap. Physica Scripta 2004, T112, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, E.A.; Weisskoff, R.M.; Boyce, K.R.; Pritchard, D.E. Mode coupling in a Penning trap: π pulses and a classical avoided crossing. Phys. Rev. A 1990, 41, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, S.; Alonso, J.; Djekić, S.; Kluge, H.J.; Quint, W.; Verdú, J.; Vogel, M. Phase-sensitive measurement of trapped particle motions. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2005, 38, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.S.; Gabrielse, G. Geonium theory: Physics of a single electron or ion in a Penning trap. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1986, 58, 233–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozar, D.M. Microwave Engineering; Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Peil, E. Quantum Jumps between Fock States of an Ultracold Electron Cyclotron Oscillator. Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, L.E.; Keil, T.H.; Narducci, L.M. Quantum-Mechanical Description of Two Coupled Harmonic Oscillators. Phys. Rev. 1968, 175, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehmelt, H.G. Continuous Stern-Gerlach effect: Principle and idealized apparatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 2291–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermanspahn, N.; Häffner, H.; Kluge, H.J.; Quint, W.; Stahl, S.; Verdú, J.; Werth, G. Observation of the continuous Stern-Gerlach effect on an electron bound in an atomic Ion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindell, I.V. On the “quasi”-TEM modes in inhomogeneous multiconductor transmission lines. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Techn. 1981, MTT-29, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.N.; Arora, R. Coupled Slot Line field components. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 1982, MTT-30, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadell, B.C. Transmission Line Design Handbook; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, J.J. Modern Quantum Mechanics; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Crimin, F.; Sussex University, Brighton, UK. Private Communication, 2016.

- Krupka, J.; Derzakowski, K.; Tobar, M.; Hartnett, J.; Geyer, R.G. Complex permittivity of some ultralow loss dielectric crystals at cryogenic temperatures. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1999, 10, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; Huang, R.S.; Wallraff, A.; Girvin, S.M.; Schoelkopf, R.J. Cavity quantum electrodynamics for superconducting electrical circuits: An architecture for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 69, 062320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallraff, A.; Schuster, D.I.; Blais, A.; Frunzio, L.; Huang, R.S.; Majer, J.; Kumar, S.; Girvin, S.M.; Schoelkopf, R.J. Strong coupling of a single photon to a superconducting qubit using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature 2004, 431, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cridland, A.; Lacy, J.H.; Pinder, J.; Verdú, J. Single Microwave Photon Detection with a Trapped Electron. Photonics 2016, 3, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics3040059

Cridland A, Lacy JH, Pinder J, Verdú J. Single Microwave Photon Detection with a Trapped Electron. Photonics. 2016; 3(4):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics3040059

Chicago/Turabian StyleCridland, April, John Henry Lacy, Jonathan Pinder, and José Verdú. 2016. "Single Microwave Photon Detection with a Trapped Electron" Photonics 3, no. 4: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics3040059

APA StyleCridland, A., Lacy, J. H., Pinder, J., & Verdú, J. (2016). Single Microwave Photon Detection with a Trapped Electron. Photonics, 3(4), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics3040059