An Adaptive Optical Limiter Based on a VO2/GaN Thin Film for Infrared Lasers

Abstract

1. Introduction

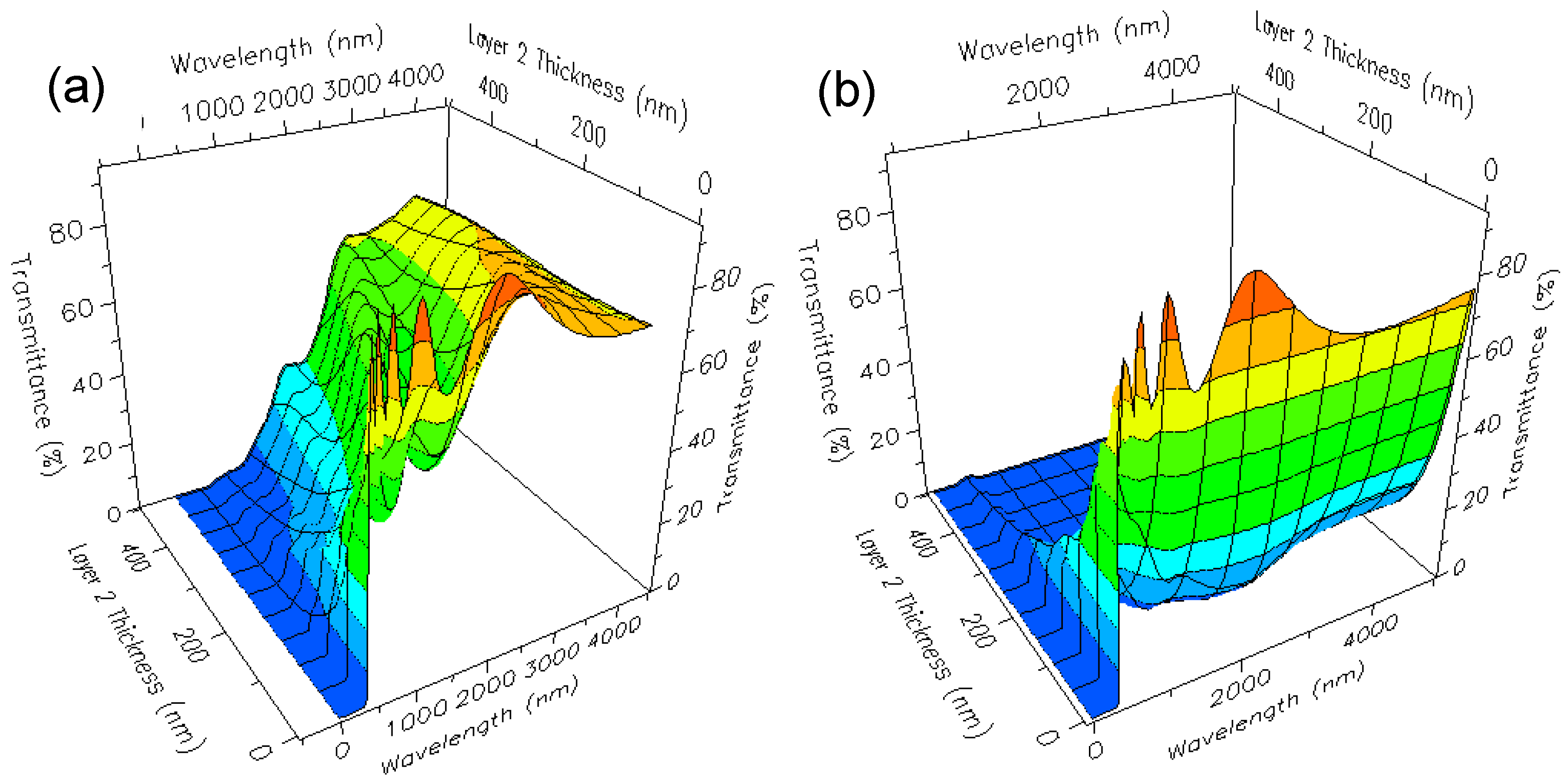

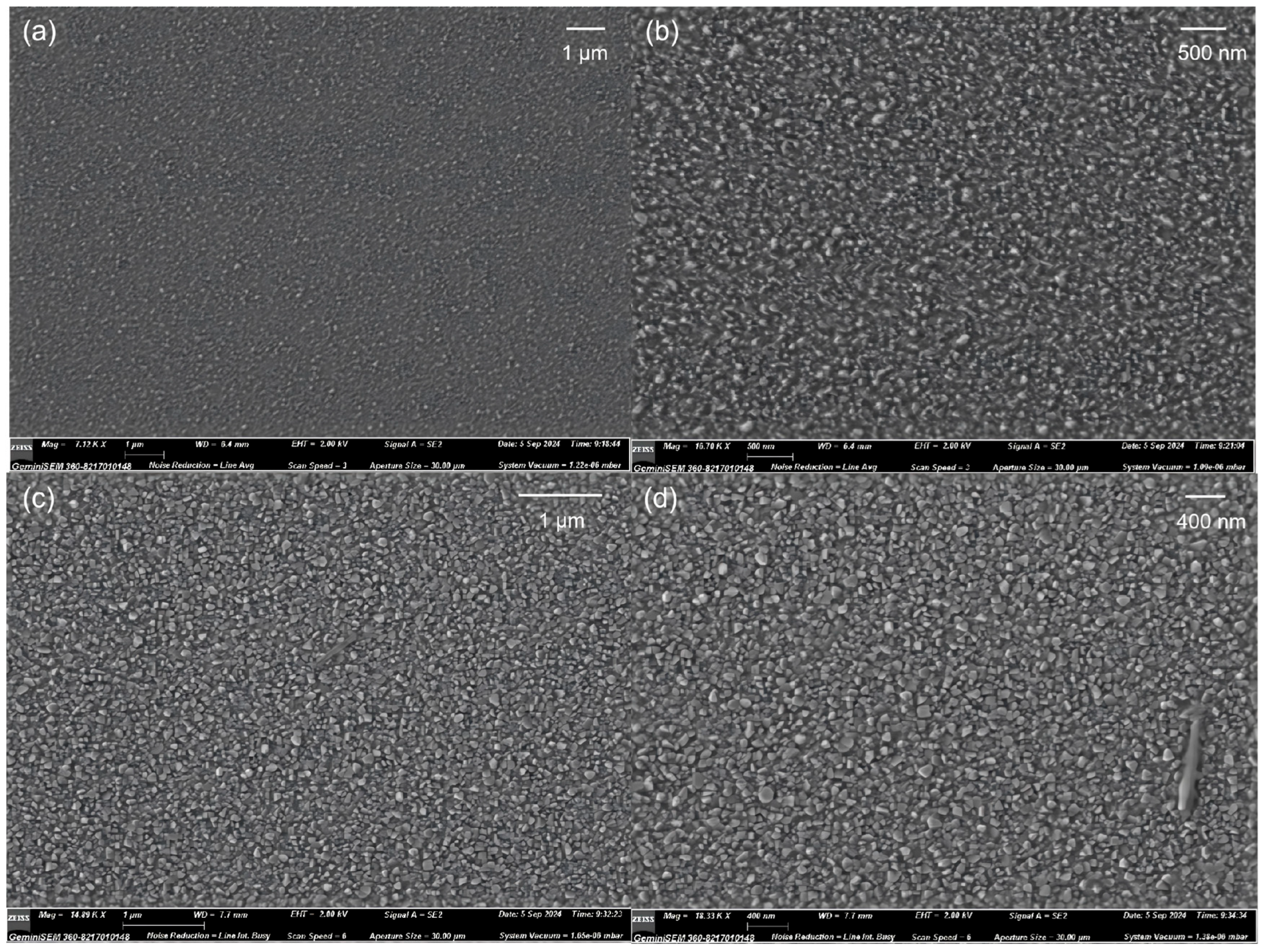

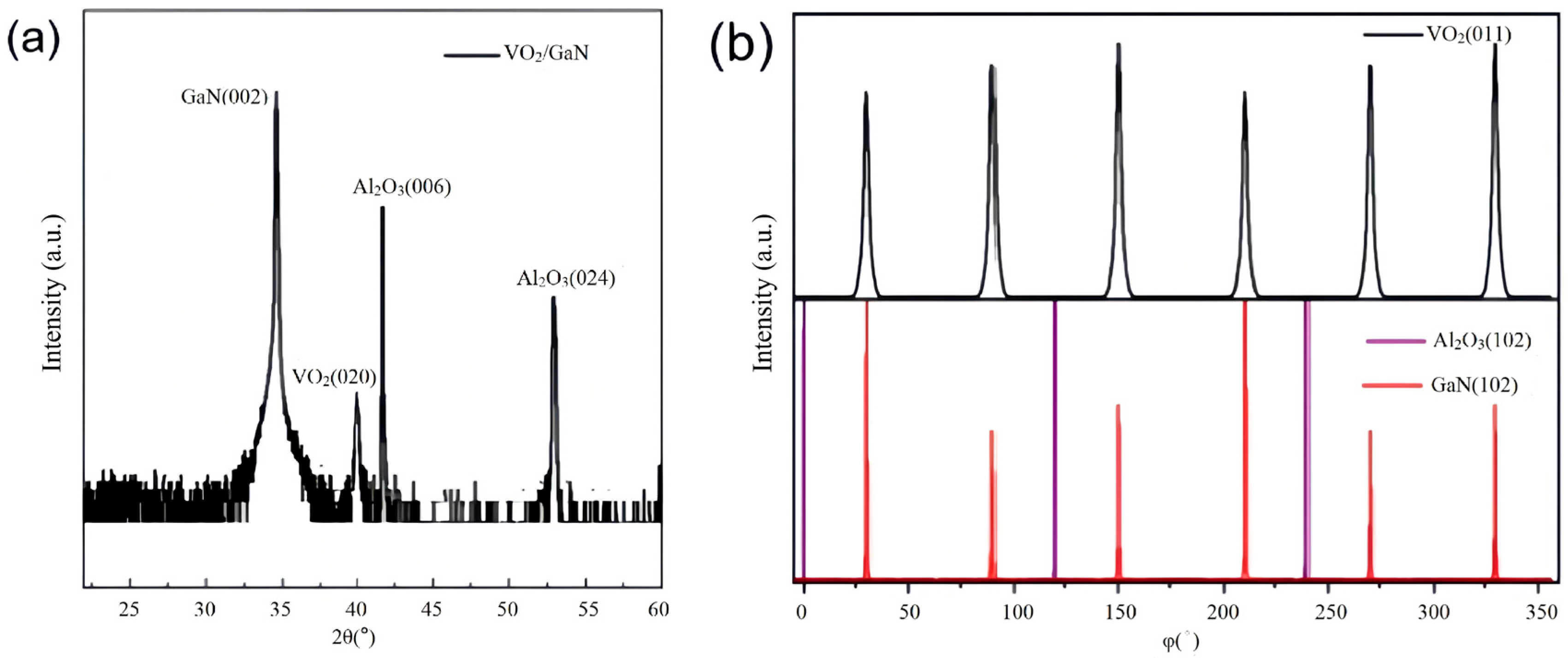

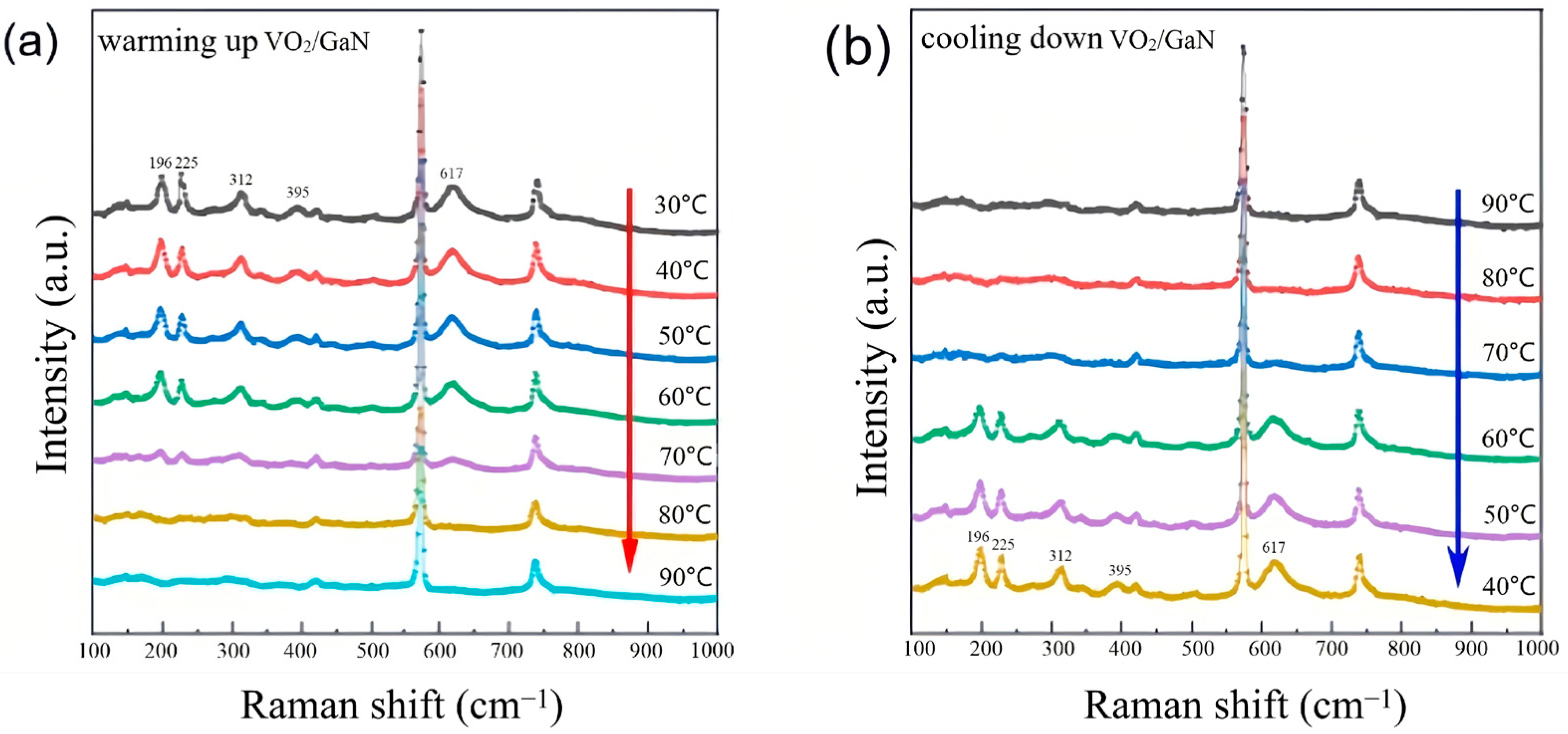

2. Materials and Methods

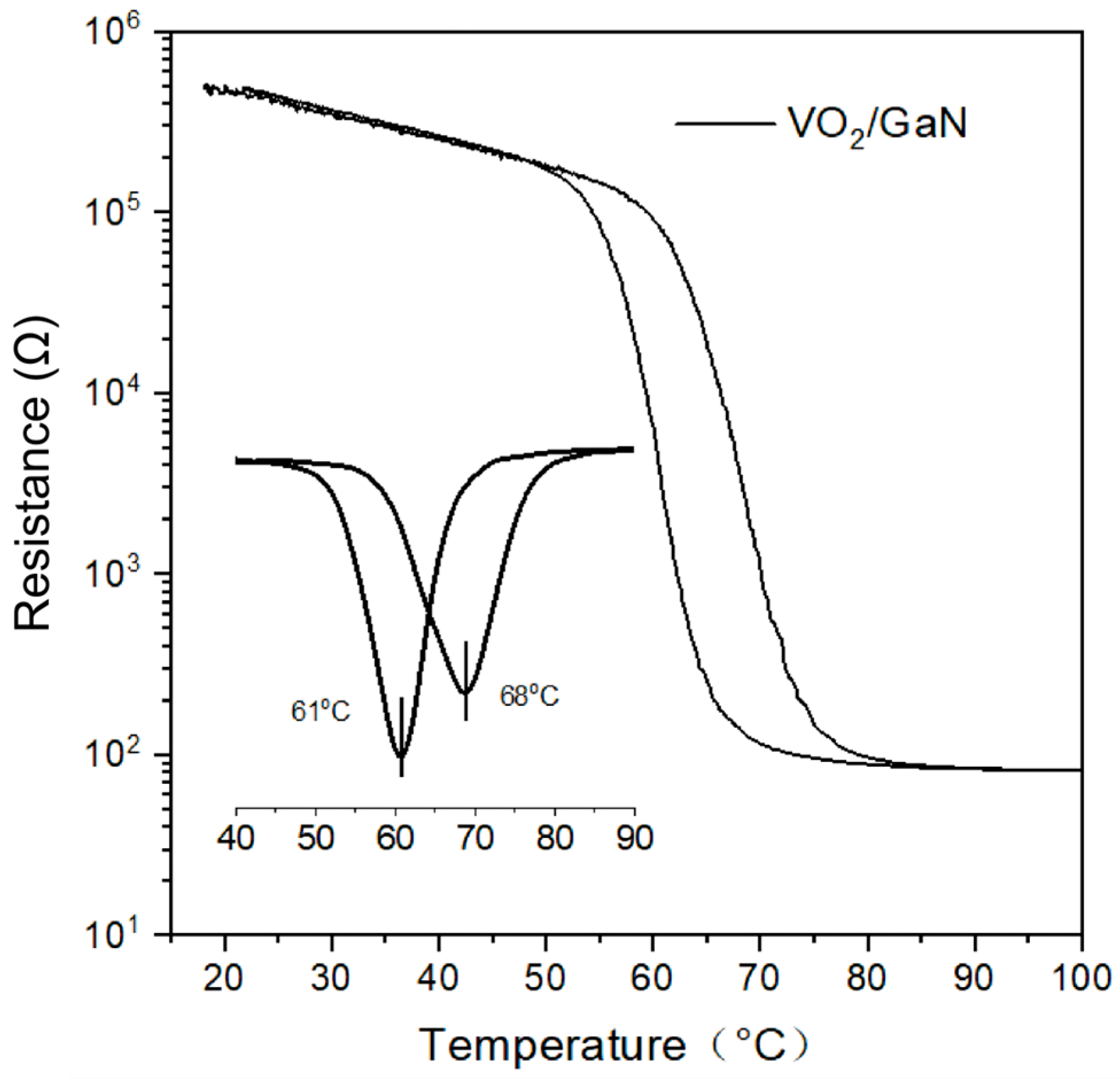

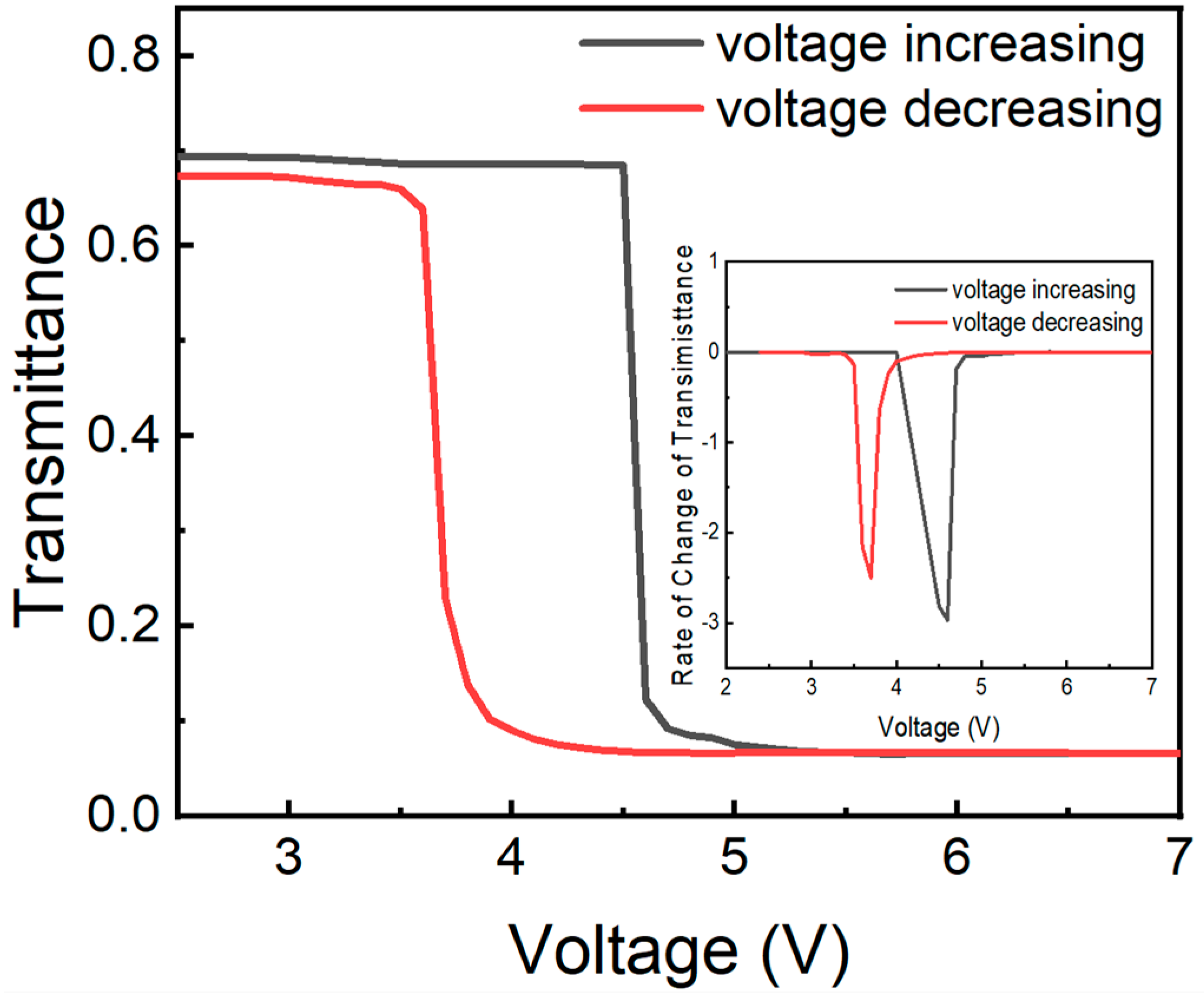

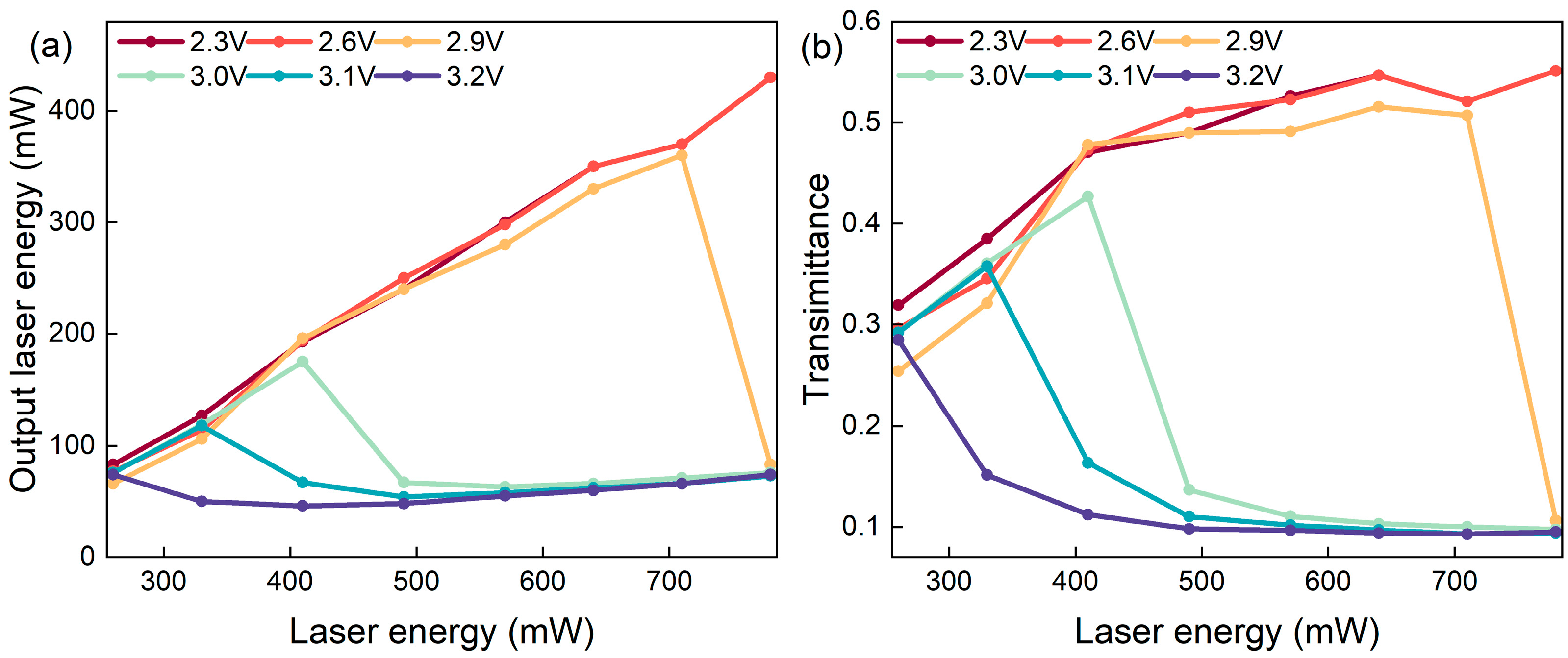

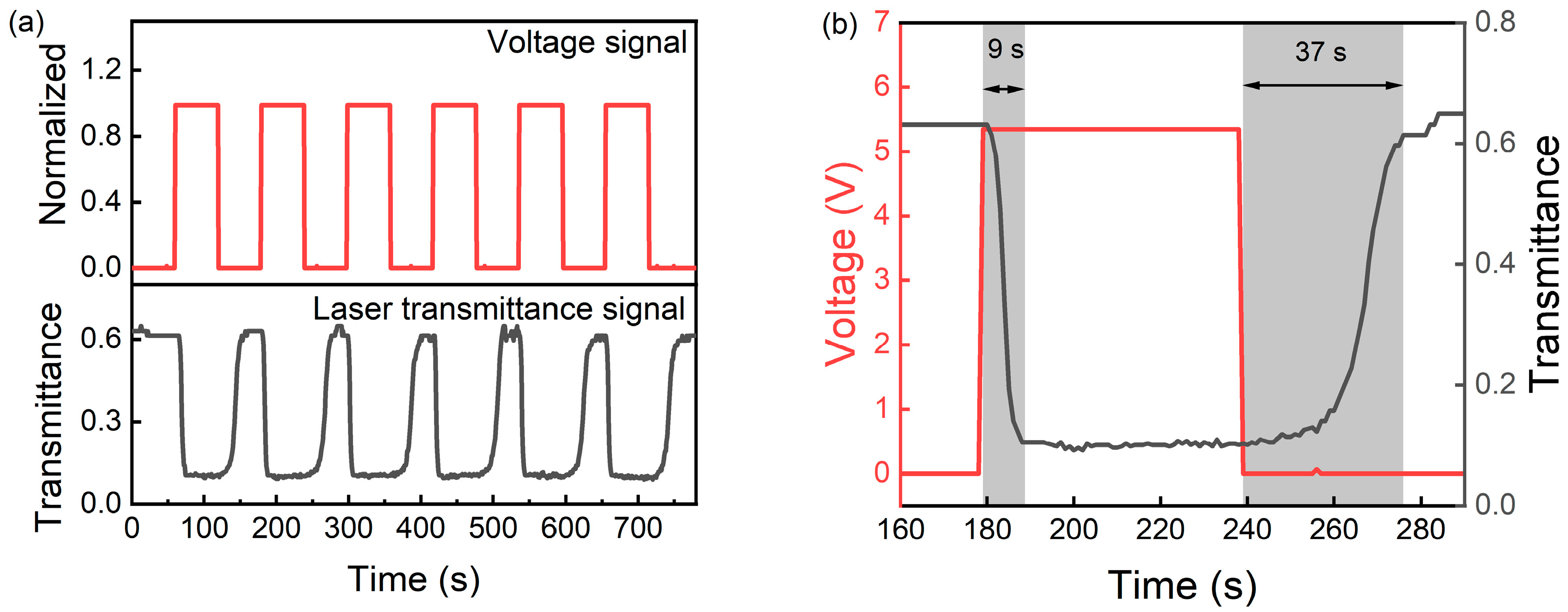

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morin, F.J. Oxides which Show a Metal-to-Insulator Transition at the Neel Temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1959, 3, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, R. Phase Transition Characteristics of VO2 Thin Films Irradiated by Multiband Infrared Laser Studied by Using Pump Probe Method. Acta Photonica Sin. 2018, 47, 1231002. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Liu, R.; Hu, J. Experiments and Theoretical Calculations of VO2 Thin Films Irradiated by Pulsed Laser. Acta Photonica Sin. 2018, 47, 1031001. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K.H.; Yun, S.J.; Slusar, T.; Kim, H.; Roh, T.M. Highly transparent ultrathin vanadium dioxide films with temperature-dependent infrared reflectance for smart windows. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 589, 152962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; Wan, C.; Park, T.J.; Deshpande, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ramanathan, S.; Kats, M.A. Electrically tunable VO2–metal metasurface for mid-infrared switching, limiting and nonlinear isolation. Nat. Photon. 2024, 18, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ou, W.; Zhao, L.; Shi, W.; Zhu, H.; Liu, J. Effect of SiO2 monocrystalline substrate orientation on the crystal structure properties of VO2 film. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Wang, L.; Yang, C.; Cao, X. Strain-Free Vanadium Dioxide Films with Stable Phase-Transition Temperatures for Flexible Phase Change Devices. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2014, 7, 12445–12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, Z.; Peng, J.; Wu, C.; Yang, Y.; Feng, F.; Gao, P.; Yang, J.; Xie, Y. Ultrahigh Infrared Photoresponse from Core-Shell Singleomain VO2/V2O5 Heterostructure in Nanobeam. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 1821–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ko, C.; Ramanathan, S. Oxide Electronics Utilizing Ultrafast Metal-Insulator Transitions. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2011, 41, 37–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, J.A.; Basaran, A.C.; Pofelski, A.; Wang, T.D.; Palin, V.; Zhu, Y.; Schuller, I.K. Ultrathin VO2 Films on Functional Substrates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 22992–23002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bercea, A.I.; Champeaux, C.; Boulle, A.; Constantinescu, C.D.; Cornette, J.; Colas, M.; Vedraine, S.; Dumas-Bouchiat, F. Adaptive gold/vanadium dioxide periodic arrays for infrared optical modulation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 585, 152592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, J.; Taylor, S.; Wang, L. Design energy analysis of tunable nanophotonic infrared filter based on thermochromic vanadium dioxide. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2022, 186, 122515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, K.; Tomioka, M.; Yamada, Y.; Horibe, A. Absorptivity Control Over the Visible to Mid-Infrared Range Using a Multilayered Film Consisting of Thermochromic Vanadium Dioxide. Int. J. Thermophys. 2022, 43, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, S.; Lee, S.; Han, J.; Lee, Y.W. Dimension Effect of Sapphire Substrate in Current-Switching Device Based on Vanadium Dioxide Thin Film Controlled by Photothermal Effect. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2021, 21, 4285–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Zhu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Xi, W.; Hu, R.; Luo, X. Temporally-adjustable radiative thermal diode based on metal-insulator phase change. Int. J. Heat Mas. Tran. 2022, 185, 122443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Xiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, B.; Gao, X.; Wang, E.; Jiang, K.; Liu, K.; Zhang, X. Wafer-scale freestanding vanadium dioxide film. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabk3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, V.R.; Chatelain, R.P.; Tiwari, K.L.; Hendaoui, A.; Bruhacs, A.; Chaker, M.; Siwick, B.J. A Photoinduced Metal-like Phase of Monoclinic VO2 Revealed by Ultrafast Electron Diffraction. Science 2014, 346, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wang, C.; Li, R.; Cai, T.; Zhang, D. Tunable Infrared Optical Switch Based on Vanadium Dioxide. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Woolf, D.; Hessel, C.M.; Salman, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yao, C.; Wright, A.; Hensley, J.M.; Kats, M.A. Switchable Induced-Transmission Filters Enabled by Vanadium Dioxide. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joushaghani, A.; Jeong, J.; Paradis, S.; Alain, D.; Aitchison, J.S.; Poon, J.K.S. Voltage-Controlled Switching and Thermal Effects in VO2 Nano-Gap Junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 221904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovich, G.; Pergament, A.; Stefanovich, D. Electrical Switching Mott Transition in VO2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2000, 12, 8837–8845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Bienz, S.; Hansen, V.F.; Zenobi, R.; Kumar, N. Nanoscale Structural Insights into Thermochromic VO2 Thin Films Using Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 32625–32634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Salman, J.; King, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, Z.; Shahsafi, A.; Wambold, R.; Ramanathan, S.; Kats, M.A. Ultrathin Broadband Reflective Optical Limiter. Laser Photonics Rev. 2021, 15, 2100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotkov, E.S.; Baburin, A.S.; Ryzhikov, I.A.; Sorokina, O.S.; Ivanov, A.I.; Zverev, A.V.; Ryzhkov, V.V.; Bykov, I.V.; Baryshev, A.V.; Panfilov, Y.V.; et al. ITO film stack engineering for low-loss silicon optical modulators. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhang, D.; He, Q.; Zeng, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, A.; Cai, X.; Ye, F.; Fan, P. Independent regulation of electrical properties of VO2 for low threshold voltage electro-optic switch applications. Sens. Actuators A-Phys. 2022, 335, 113394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhou, L.; Li, B.; Tian, S.; Zhao, X. Enhanced Thermochromic Performance of VO2 Nanoparticles by Quenching Process. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, P.; Juan, N.A.; Mariela, M.; Maria, P.; Jean-Pierre, L.; Pablo, S. Low-threshold power and tunable integrated optical limiter based on an ultracompact VO2/Si waveguide. APL Photonics 2021, 6, 121301. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Lei, Y.; Li, Q.; Xie, J.; Yang, J.; Jin, H.; Chen, P.; Li, J. Laser damage mechanism of VO2/Al2O3 films numerical simulation. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.L.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.F.; Chen, F.H.; Chu, W.S.; Chen, X.; Zou, C.W.; Wu, Z.Y. Growth and Phase Transition Characteristicsof Pure M-phase VO2 epitaxial Film Prepared by Oxide Molecular Beam Epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 131914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova-Martínez, P.; Hernandez-Velasco, J.; Landa-Canovas, A.R.; Agullo-Rueda, F. Laser heating induced phase changes of VO2 crystals in air monitored by Raman spectroscopy. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 661, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material System | Threshold (Power/Voltage) | Response Time (Rise/Fall) | Modulation Depth | Operating Wavelength | Key Features | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VO2/ITO film | 1.4 V (electrical) | 0.24 ms/2.1 ms | 35% | Not specified | Low threshold voltage Fast response Small-scale device | [25] |

| VO2-metal metasurface | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Mid-IR | Electrically tunable Nanophotonic structure Limited scalability | [5] |

| VO2/Si waveguide | 3.5 mW (optical) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Ultra-compact Low optical threshold On-chip integration only | [26] |

| Ultrathin VO2-based limiter | Not specified | Not specified | Broadband | Mid-IR | Broadband reflection Plasma-enhanced Small-area fabrication | [23] |

| Al nanoarrays/VO2 | Optical power threshold | Not specified | ~99.4% | 1.5 μm | Plasmonic resonance-enhanced High modulation depth | [18] |

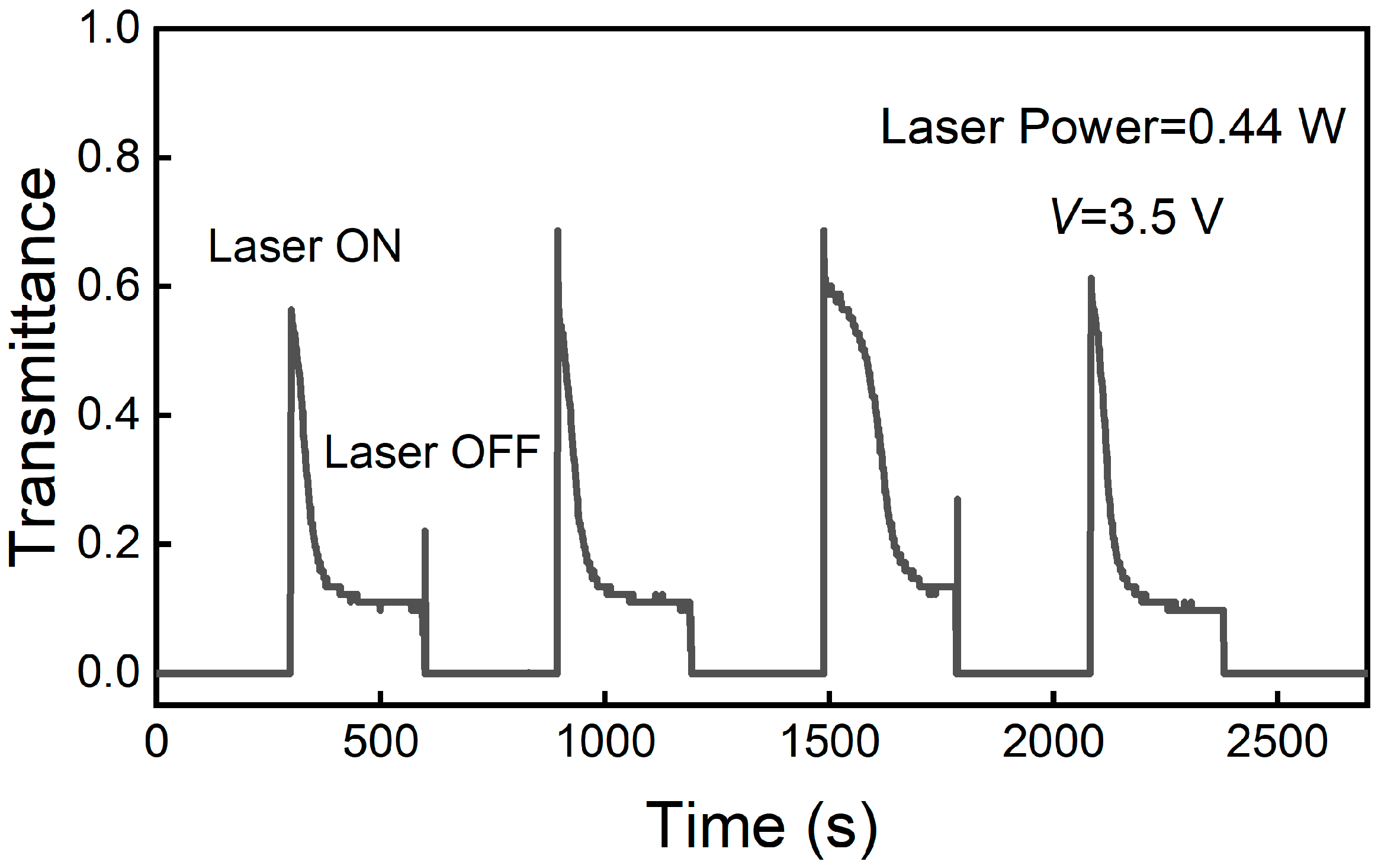

| VO2/GaN/Al2O3 heterostructure | 330 mW (at 3.5 V) | 9 s/37 s | 50% (60%→10%) | 3.7 μm (mid-IR) | Wafer-scale Electrical control High compatibility with practical applications | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Zhou, C.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Jin, W.; Wang, S.; Zhao, S.; Huang, J.; Shang, Y.; Zou, C. An Adaptive Optical Limiter Based on a VO2/GaN Thin Film for Infrared Lasers. Photonics 2026, 13, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020148

Li Y, Zhou C, Feng Y, Zhu J, Jin W, Wang S, Zhao S, Huang J, Shang Y, Zou C. An Adaptive Optical Limiter Based on a VO2/GaN Thin Film for Infrared Lasers. Photonics. 2026; 13(2):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020148

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yafan, Changqi Zhou, Yunsong Feng, Jinglin Zhu, Wei Jin, Siyu Wang, Shanguang Zhao, Jiahao Huang, Yuanxin Shang, and Congwen Zou. 2026. "An Adaptive Optical Limiter Based on a VO2/GaN Thin Film for Infrared Lasers" Photonics 13, no. 2: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020148

APA StyleLi, Y., Zhou, C., Feng, Y., Zhu, J., Jin, W., Wang, S., Zhao, S., Huang, J., Shang, Y., & Zou, C. (2026). An Adaptive Optical Limiter Based on a VO2/GaN Thin Film for Infrared Lasers. Photonics, 13(2), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020148