A Metasurface Dual-Band Cut-Off Perfect Absorber for Visible and Near-Infrared Bands

Abstract

1. Introduction

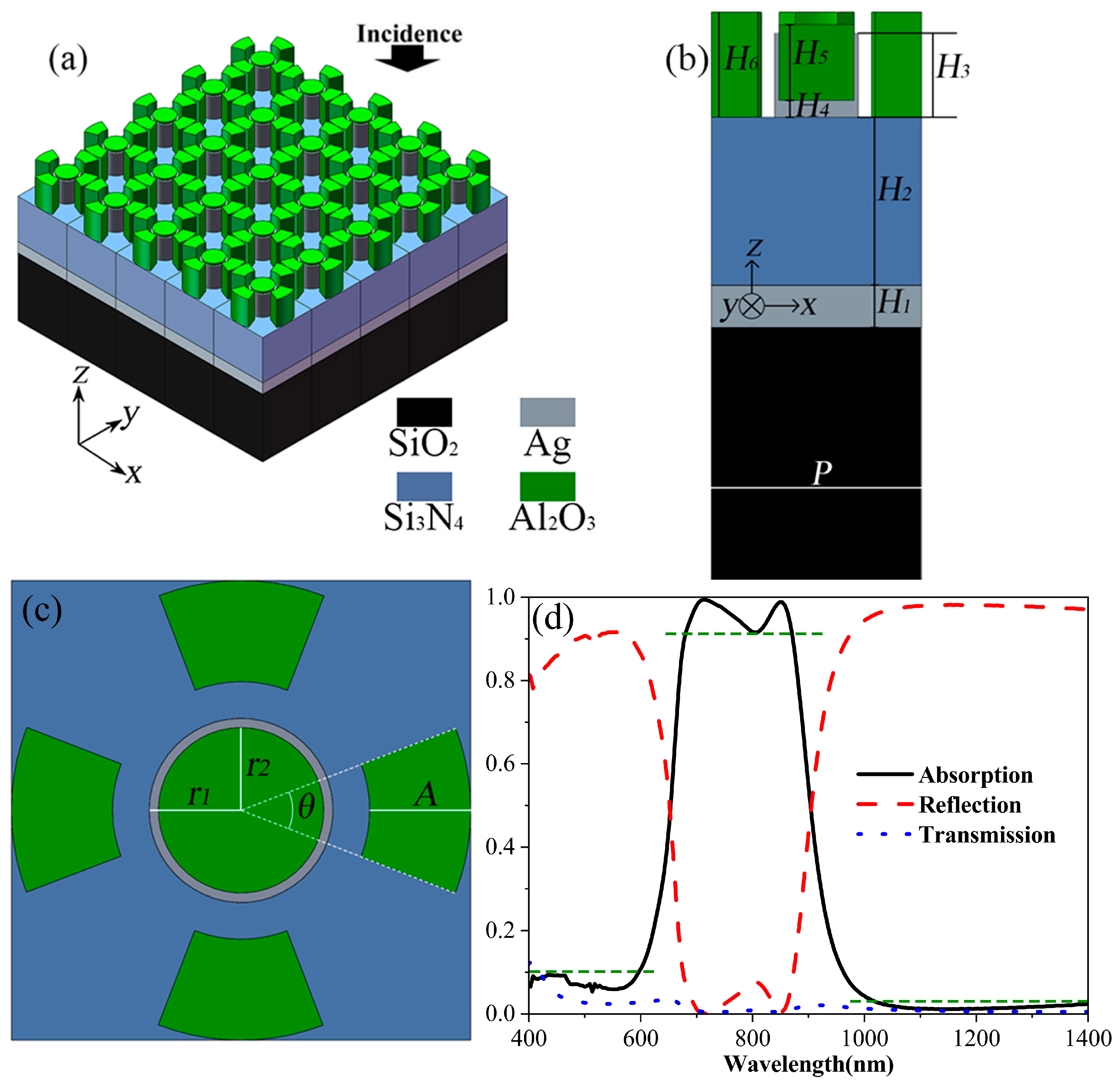

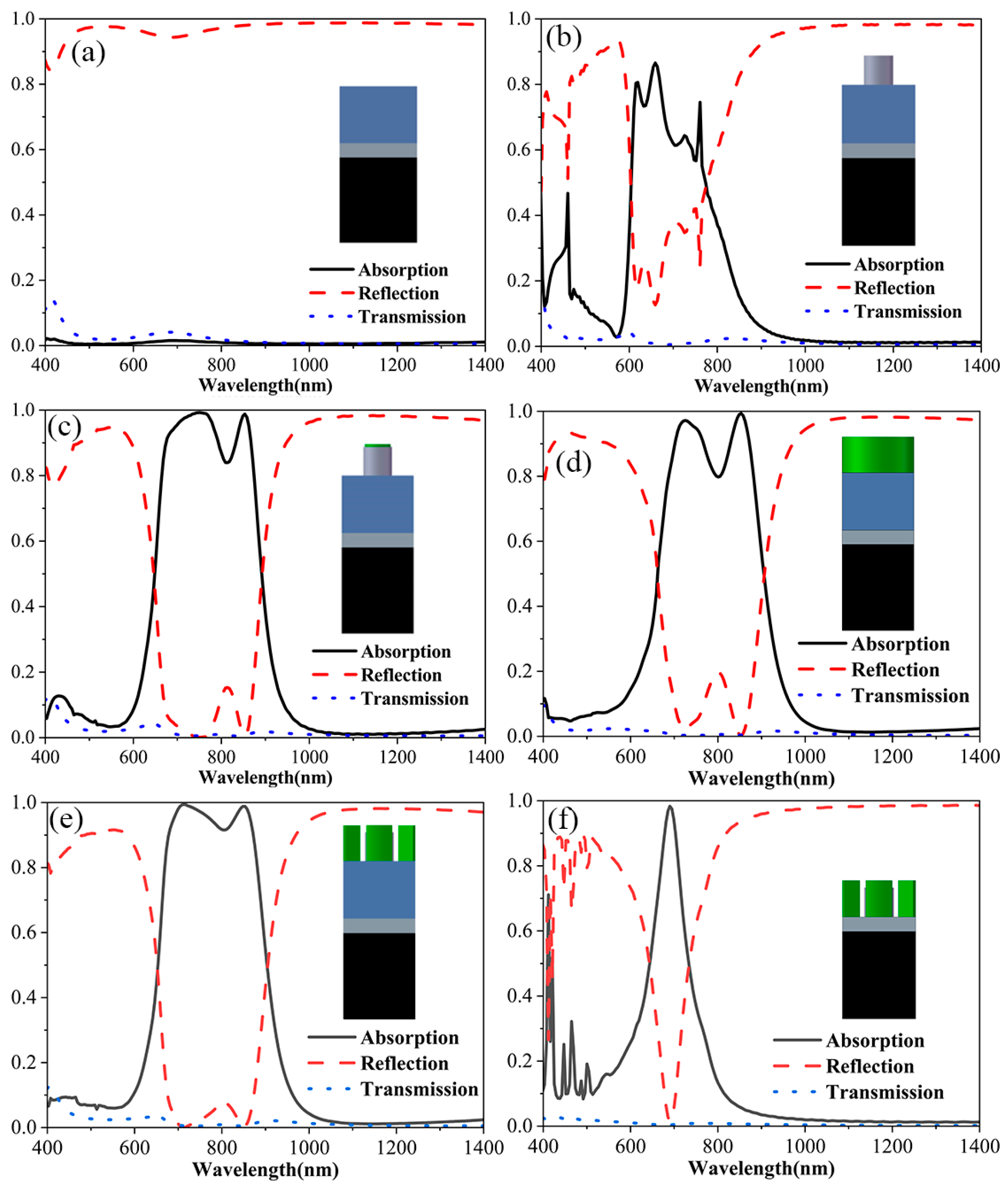

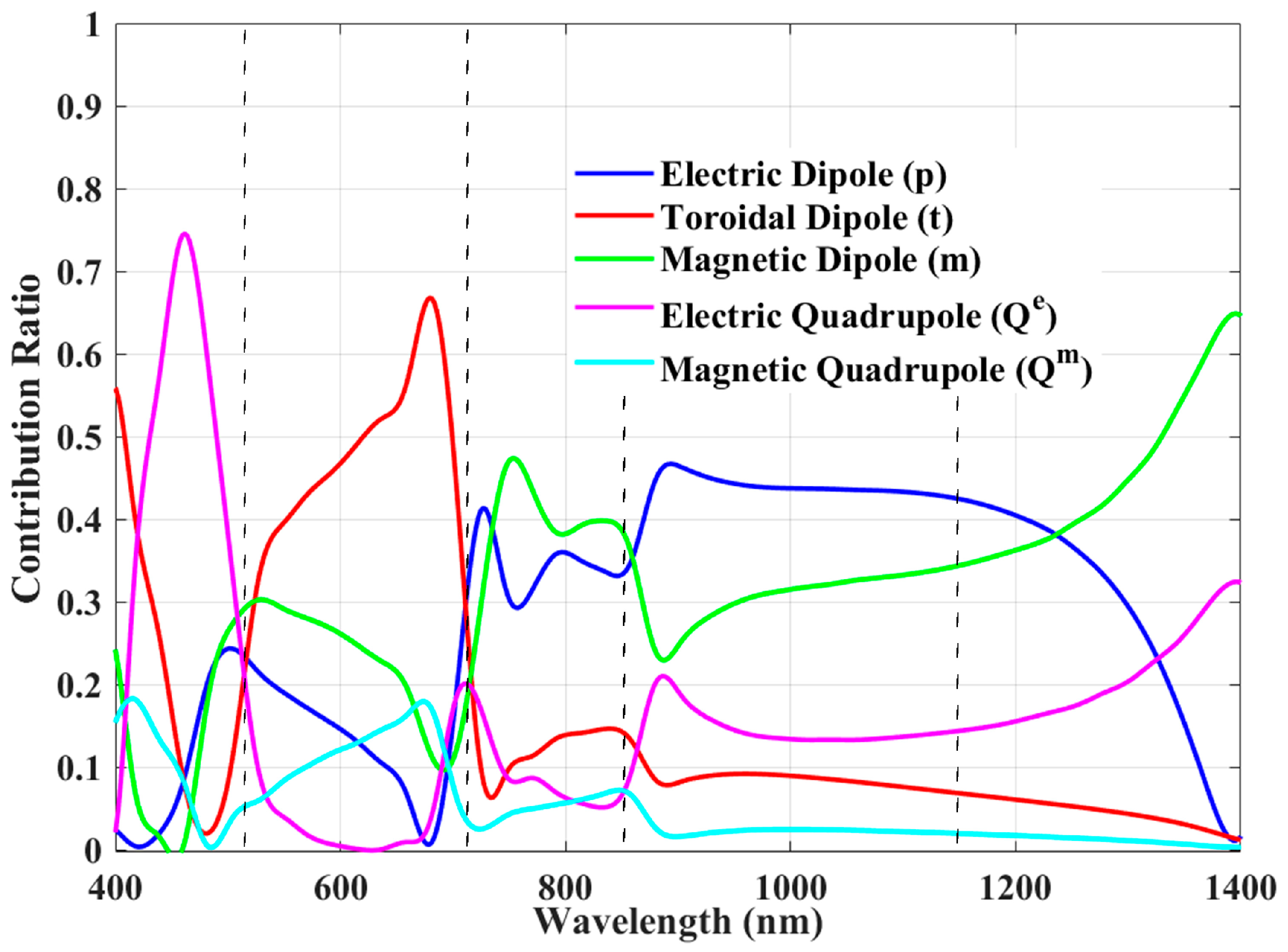

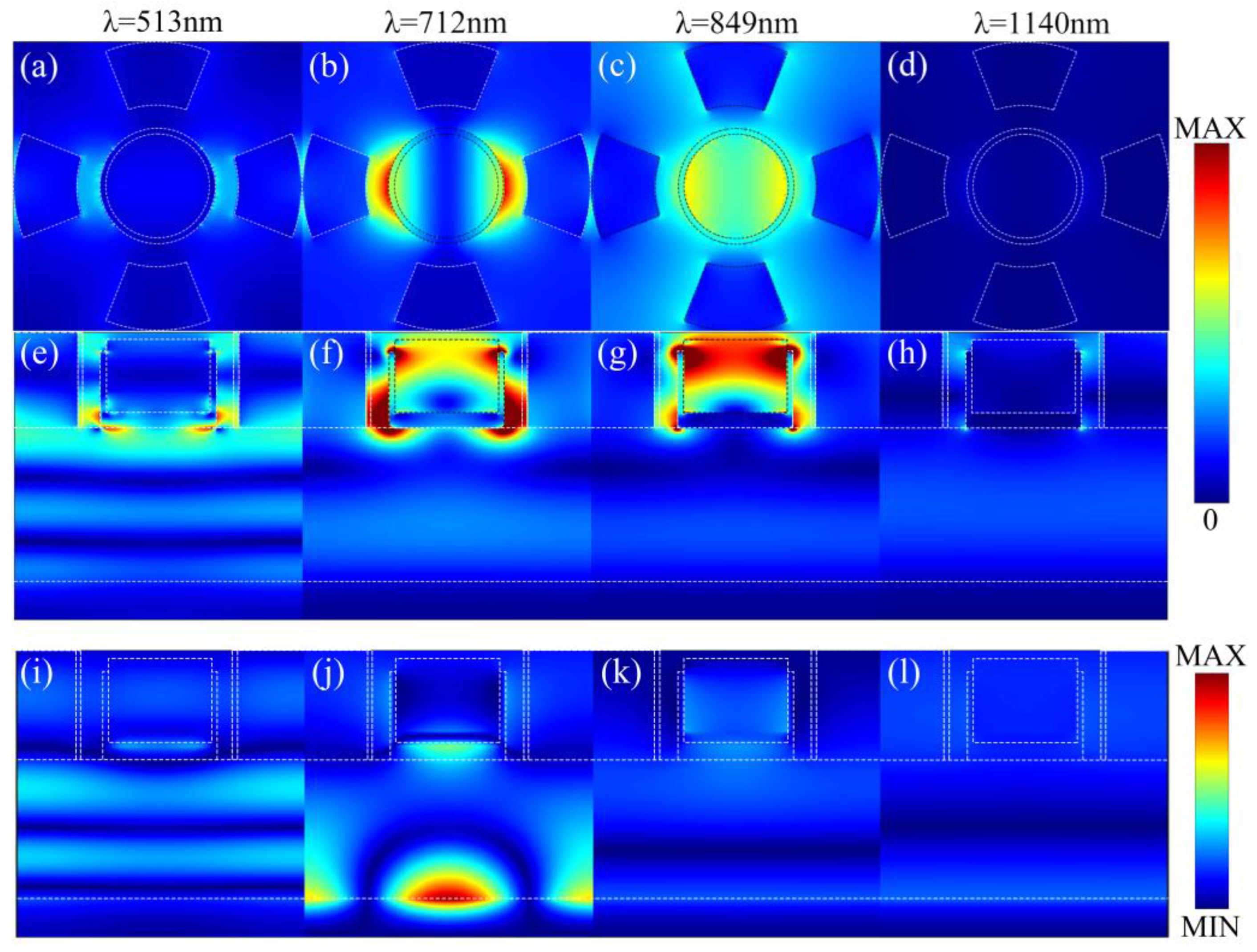

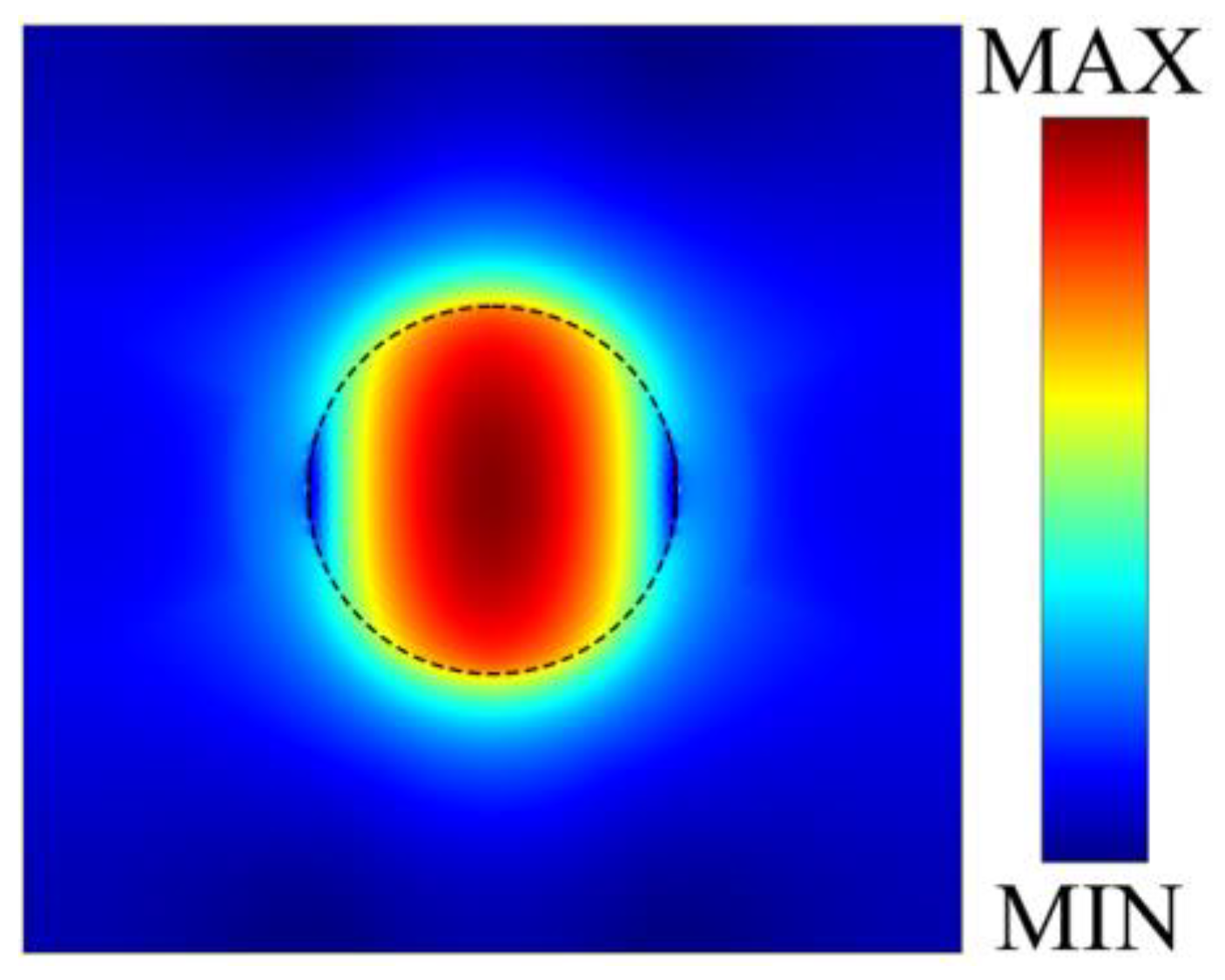

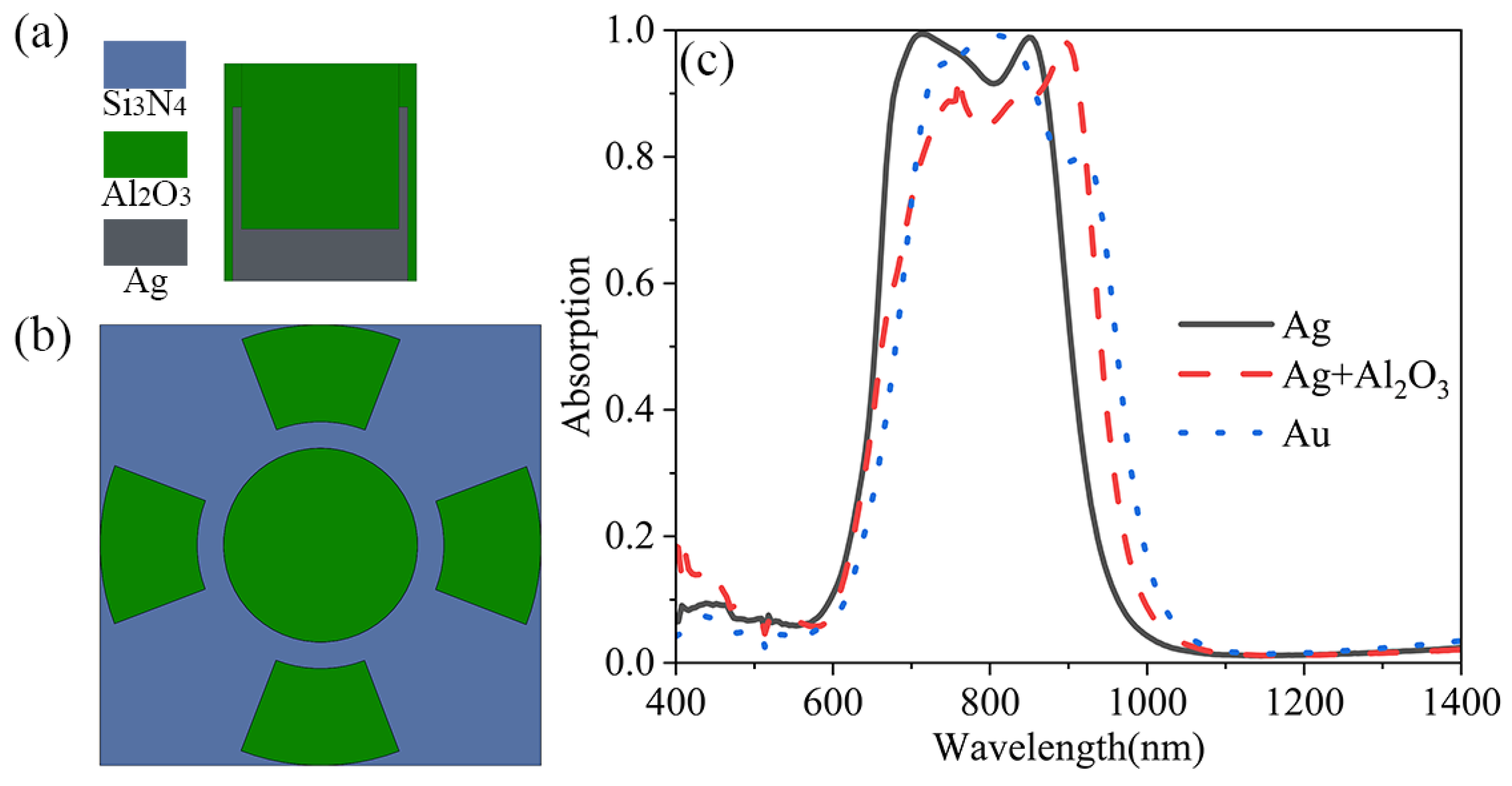

2. Design and Simulation

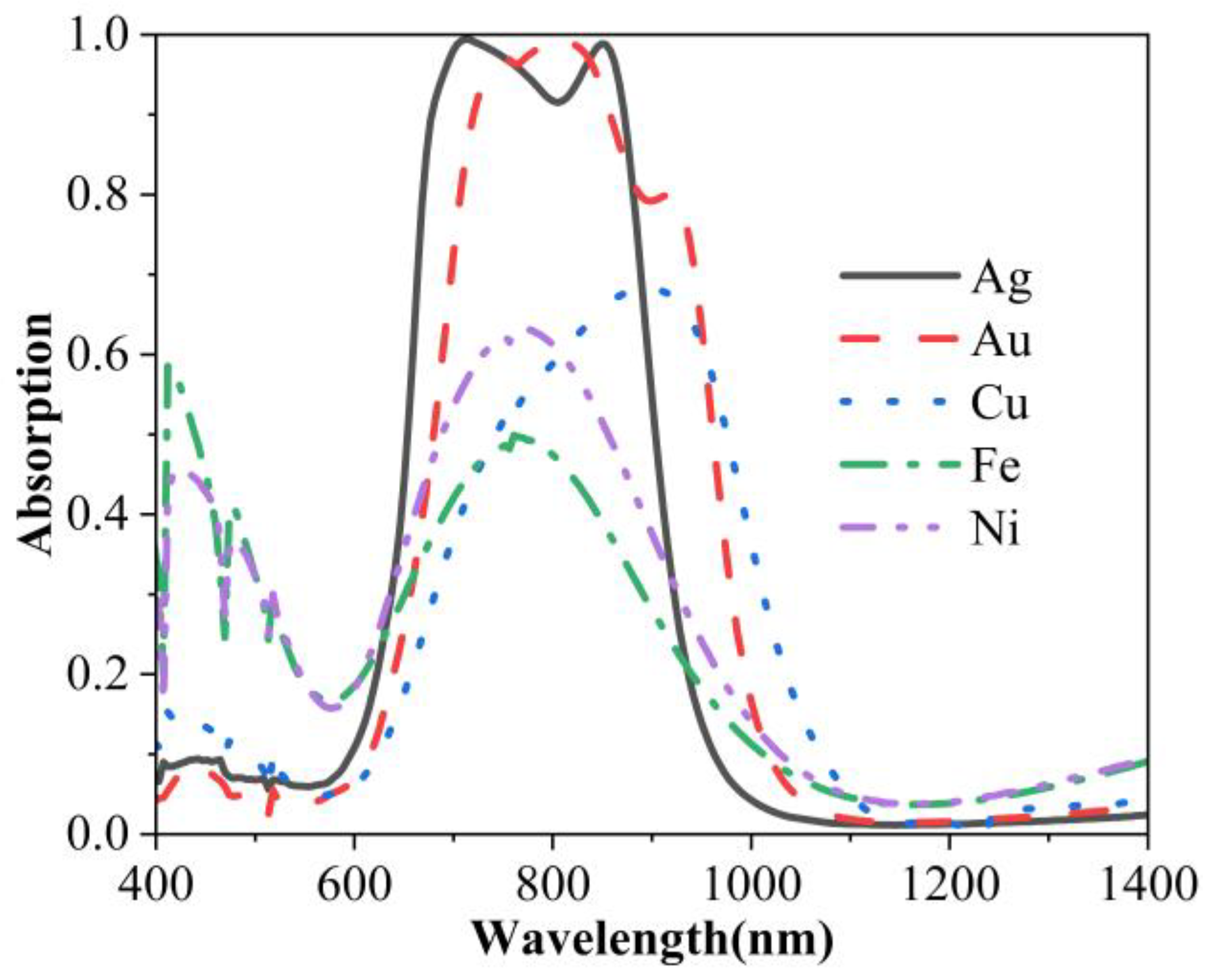

3. Theory and Mechanism

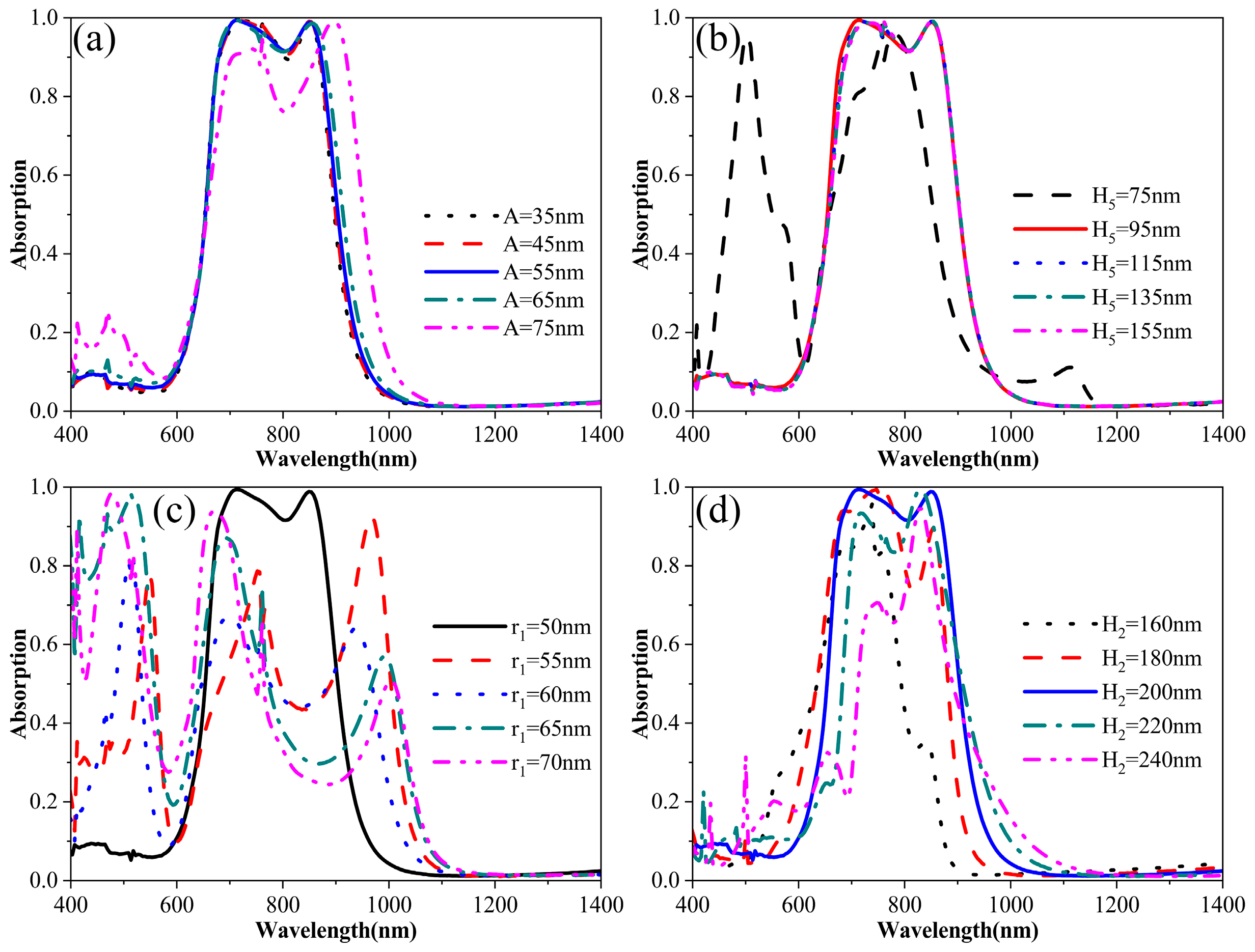

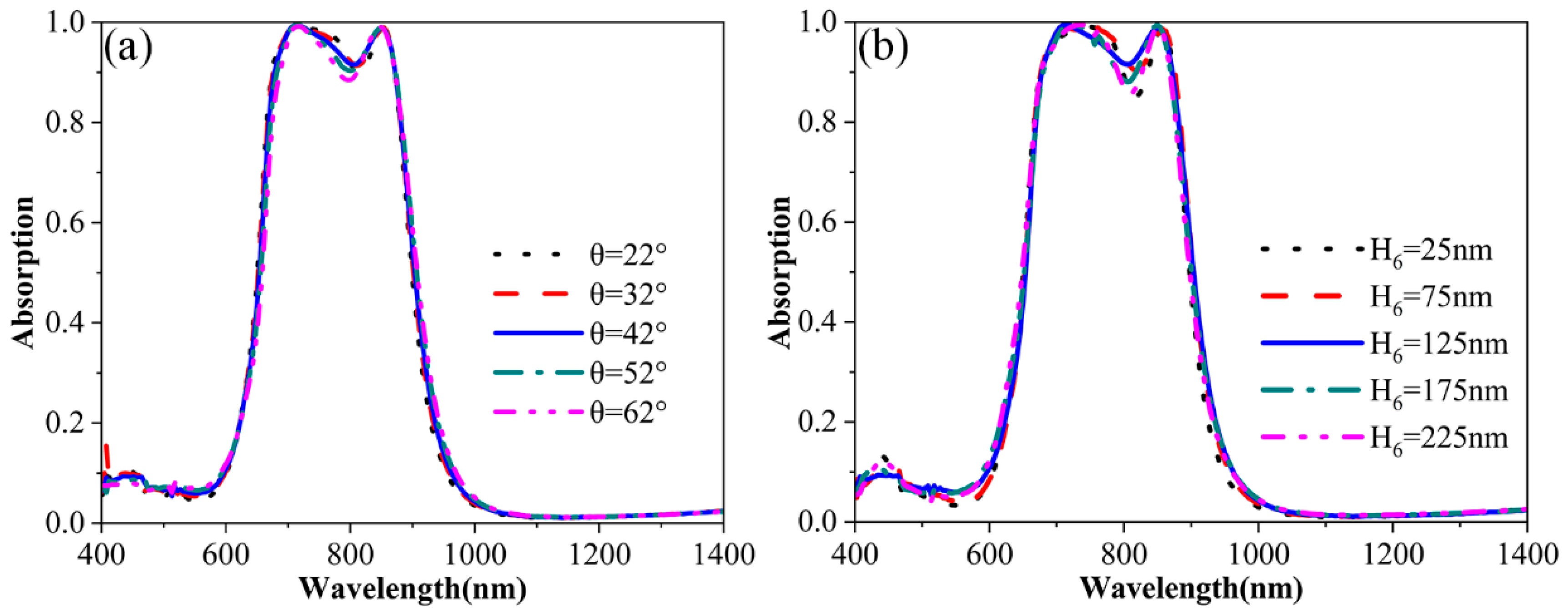

4. Discussion

5. Outlook

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ai, Z.; Liu, H.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, H.; Yi, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Wu, P.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C.; Hao, Z. Four peak and high angle tilted insensitive surface plasmon resonance graphene absorber based on circular etching square window. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2025, 58, 185305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wan, M.; Sun, M.; Lu, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, B. A dual-band mid-infrared polarization-insensitive perfect absorber. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 10523–10529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, X.; Lin, Y.S. Reconfigurable MEMS-based Perfect Meta-absorber with Ultrahigh-Q and Angle-dependent Characteristics for Sensing Applications. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, 19, 2500288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Guan, X.; Qiao, S.; Jia, Q.; He, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y. Ultrahigh Sensitive LITES Sensor Based on a Trilayer Ultrathin Perfect Absorber Coated T-Head Quartz Tuning Fork. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, 19, 2402107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assad, M.A.; Elbahri, M. Perfect ultraviolet absorbers via disordered polarizonic metasurfaces for multiband camouflage and stealth technologies. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2418271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, S.; Gao, Y.; Yao, S.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Tsai, D.P.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, W. Ultrabroadband and >93% Microwave Absorption Enabled by “Doped” Water Meta-Atom Lattice with Subwavelength Thickness. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2411153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Q.; Zhu, K.; Hao, X.; Wu, C.; Li, J.; Cheng, H.; Yan, J.; Jiang, L.; Qu, L. Bio-Inspired Ultrathin Perfect Absorber for High-Performance Photothermal Conversion. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2313366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, M.A.; Mohsin, A.S.; Bhuian, M.B.H.; Rahman, M.M. Analysis of an ultra-broadband TiN-based metasurface absorber for solar thermophotovoltaic cell in the visible to near infrared region. Sol. Energy 2024, 284, 113064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yun, H.; Jeong, S.; Lee, S.; Cho, E.; Rho, J. Optical metasurfaces for biomedical imaging and sensing. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 3085–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayli, S.V.; Patel, T.; van Kasteren, B.; Kokilathasan, S.; Tekcan, B.; Alan Tam, M.C.; Losin, W.F.; Odinotski, S.; Tsen, A.W.; Wasilewski, Z.R. Near-Unity Absorption in Semiconductor Metasurfaces Using Kerker Interference. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 9362–9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosteris, I.S.; Kliros, G.S. Analytical Design of Optically Transparent, Wideband, and Tunable Microwave Absorber Based on Graphene Spiral Resonator Metasurface. Photonics 2025, 12, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.; Yang, Y.; Jeon, Y.; Lee, C.; An, J.; Rho, J. Structurally reordered crystalline atomic layer-dielectric hybrid metasurfaces for near-unity efficiency in the visible. Mater. Today 2025, 88, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.R.; Chiang, M.F.; Ho, P.Y.; Chen, K.H.; Lee, J.H.; Hsu, P.H.; Peng, Y.C.; Hou, J.Y.; Chen, S.C.; Lee, Q.Y. Deep-UV silicon polaritonic metasurfaces for enhancing biomolecule autofluorescence and two-dimensional material double-resonance raman scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2420439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Pan, R.; Xiang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Wang, B.; Li, J. Unilateral Asymmetric Radiation in Bilayer Metasurfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2501156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fleury, R.; Seppecher, P.; Hu, G.; Wegener, M. Nonlocal metamaterials and metasurfaces. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2025, 7, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikeler, C.; Haslinger, F.; Martynenko, I.V.; Liedl, T. DNA Origami-Directed Self-Assembly of Gold Nanospheres for Plasmonic Metasurfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2404766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Kim, G.; Yun, J.; Jeon, Y.; Rho, J.; Baek, S.-H. 360° structured light with learned metasurfaces. Nat. Photonics 2024, 18, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ren, J.; Zhang, J.; Meng, J.; McManus-Barrett, C.; Crozier, K.B.; Sukhorukov, A.A. Quantum imaging using spatially entangled photon pairs from a nonlinear metasurface. eLight 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccagnini, F.; De Biase, D.; Bovieri, F.; Perotto, G.; Quagliarini, E.; Bavasso, I.; Mangino, G.; Iuliano, M.; Calogero, A.; Romeo, G. Multifunctional FFP2 face mask for white light disinfection and pathogens detection using hybrid nanostructures and optical metasurfaces. Small 2024, 20, 2400531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Kalra, Y.; Sinha, R.K. Triple-band perovskite based chiral metasurface biosensor with multi-functionalities. J. Comput. Electron. 2025, 24, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Yi, Z.; Wang, J.; Cheng, S.; Li, B.; Wu, P. High Absorption Broadband Ultra-Long Infrared Absorption Device Based on Nanoring–Nanowire Metasurface Structure. Photonics 2025, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Guo, L.; Zhang, P.; Qiu, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, J. Near-perfect spectrally-selective metasurface solar absorber based on tungsten octagonal prism array. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 16823–16834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Qian, Q.; Wang, C.; Fan, L.; Cheng, L.; Chen, H.; Zhao, L. An all-dielectric metasurface long-pass cut-off filter based on a multi-nanocircular array perfect cut-off absorber. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2022, 64, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qian, Q.; Chen, H.; Fan, L.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, L.; Wang, C. Metasurface cutoff perfect absorber in a solar energy wavelength band. Appl. Opt. 2023, 62, 7766–7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Wei, C.-W.; Simpson, R.E.; Zhang, L.; Cryan, M.J. Broadband polarization-independent perfect absorber using a phase-change metamaterial at visible frequencies. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Song, H.; Zeng, X.; Hu, H.; Liu, K.; Zhang, N.; Gan, Q. Broadband absorption engineering of hyperbolic metafilm patterns. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Hu, L.; Lu, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. Dual-band metamaterial absorbers in the visible and near-infrared regions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 10028–10033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgouei, A.K.; Hajian, H.; Serebryannikov, A.E.; Ozbay, E. Hybrid indium tin oxide-Au metamaterial as a multiband bi-functional light absorber in the visible and near-infrared ranges. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 275102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Binda, P.; Dey, U. Investigations on a Triple-Band Metasurface Absorber as THz-Biomedical Sensor. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2024, 52, 3051–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossifos, K.M.; Petrou, L.; Varnava, G.; Pitilakis, A.; Tsilipakos, O.; Liu, F.; Karousios, P.; Tasolamprou, A.C.; Seckel, M.; Manessis, D. Toward the realization of a programmable metasurface absorber enabled by custom integrated circuit technology. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 92986–92998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekalao, J.; Elsayed, H.A.; Alqhtani, H.A.; Abukhadra, M.R.; Bellucci, S.; Mehaney, A.; Rajakannu, A. High-efficiency graphene-based metasurface absorber with T-shaped resonators for broadband solar energy harvesting in renewable energy applications. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 2849–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Panday, A.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, L.; Ji, C.; Guo, L.J. Visualizing Mie resonances in low-index dielectric nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 253902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Li, S.; Huang, H.; Tao, K.; Xu, P. Ultra-broadband absorber from visible to near-infrared using plasmonic metamaterial. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 5686–5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Huang, L.; Ding, J.; Liu, W.; Sun, B.; Xie, C.; Yang, H.; Wu, J. Flexible and transparent broadband microwave metasurface absorber based on multipolar interference engineering. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 7694–7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Kaj, K.; Chen, C.; Yang, Z.; Ul Haque, S.R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Averitt, R.D.; Zhang, X. Broadband terahertz silicon membrane metasurface absorber. ACS Photonics 2022, 9, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, X.; Ma, C.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Guan, B.-O.; Chen, K. Ultra-narrow-band metamaterial perfect absorber based on surface lattice resonance in a WS2 nanodisk array. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 27084–27091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsilipakos, O.; Tasolamprou, A.C.; Koschny, T.; Kafesaki, M.; Economou, E.N.; Soukoulis, C.M. Pairing toroidal and magnetic dipole resonances in elliptic dielectric rod metasurfaces for reconfigurable wavefront manipulation in reflection. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1800633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolly, B.; Bebey, B.; Bidault, S.; Stout, B.; Bonod, N. Promoting magnetic dipolar transition in trivalent lanthanide ions with lossless Mie resonances. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2012, 85, 245432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Y. Multi-electron transfer mechanism and band structures of CNTs in MOF-derived CNTs/Co hybrids for enhanced electromagnetic wave absorption property. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Fang, Y. Fabry-Pérot interference cavity length tuned by plasmonic nanoparticle metasurface for nanophotonic device design. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 10732–10738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.R.; Ishii, S.; Naik, G.V.; Emani, N.K.; Shalaev, V.M.; Boltasseva, A. Searching for better plasmonic materials. Laser Photonics Rev. 2010, 4, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; He, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Dan, Z.; Ma, L.; Yang, M.; Liu, D.; Huang, X.; Zhong, B. Controlled phase and structure engineering-driven unique dielectric behavior enabling tailored electromagnetic attenuation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemasters, R.; Zhang, C.; Manjare, M.; Zhu, W.; Song, J.; Urazhdin, S.; Lezec, H.J.; Agrawal, A.; Harutyunyan, H. Ultrathin wetting layer-free plasmonic gold films. ACS Photonics 2019, 6, 2600–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indhu, A.; Dharanya, C.; Dharmalingam, G. Plasmonic copper: Ways and means of achieving, directing, and utilizing surface plasmons. Plasmonics 2024, 19, 1303–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmatpour, E.; Rahmani, M. Ab initio investigation of electronic and optical properties of three quaternary types: CuMn2InSe4, CuMn2InTe4 and CuNi2InTe4. Optik 2022, 266, 169663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; Qin, X.; Duan, G.; Yang, G.; Huang, W.Q.; Huang, Z. Dielectric-based metamaterials for near-perfect light absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AB (nm) | ERal (dB) | ERar (dB) | EDal | EDar | CSal (nm−1) | CSar (nm−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200–447 | N/A * | 12.17 | N/A | 0.88 | N/A | 0.0047 | [23] |

| 100–700 | N/A | 9.4 | N/A | 0.80 | N/A | 0.0019 | [24] |

| 545–975 | 6.53 | 4.49 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.007 | 0.002 | [25] |

| 760–900 | 5.02 | 6.90 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.004 | 0.004 | [27] |

| 676–872 | 9.95 | 11.36 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.011 | 0.008 | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, Z.; Qian, Q.; Chen, H.; Cheng, L.; Fan, L.; Zhao, L.; Wang, C. A Metasurface Dual-Band Cut-Off Perfect Absorber for Visible and Near-Infrared Bands. Photonics 2026, 13, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020131

Ma Z, Qian Q, Chen H, Cheng L, Fan L, Zhao L, Wang C. A Metasurface Dual-Band Cut-Off Perfect Absorber for Visible and Near-Infrared Bands. Photonics. 2026; 13(2):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020131

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Zhibo, Qinyu Qian, Haitao Chen, Liwen Cheng, Li Fan, Liang Zhao, and Chinhua Wang. 2026. "A Metasurface Dual-Band Cut-Off Perfect Absorber for Visible and Near-Infrared Bands" Photonics 13, no. 2: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020131

APA StyleMa, Z., Qian, Q., Chen, H., Cheng, L., Fan, L., Zhao, L., & Wang, C. (2026). A Metasurface Dual-Band Cut-Off Perfect Absorber for Visible and Near-Infrared Bands. Photonics, 13(2), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020131