Non-Uniform Modal Power Distribution Caused by Disorder in Multimode Fibers

Abstract

1. Introduction

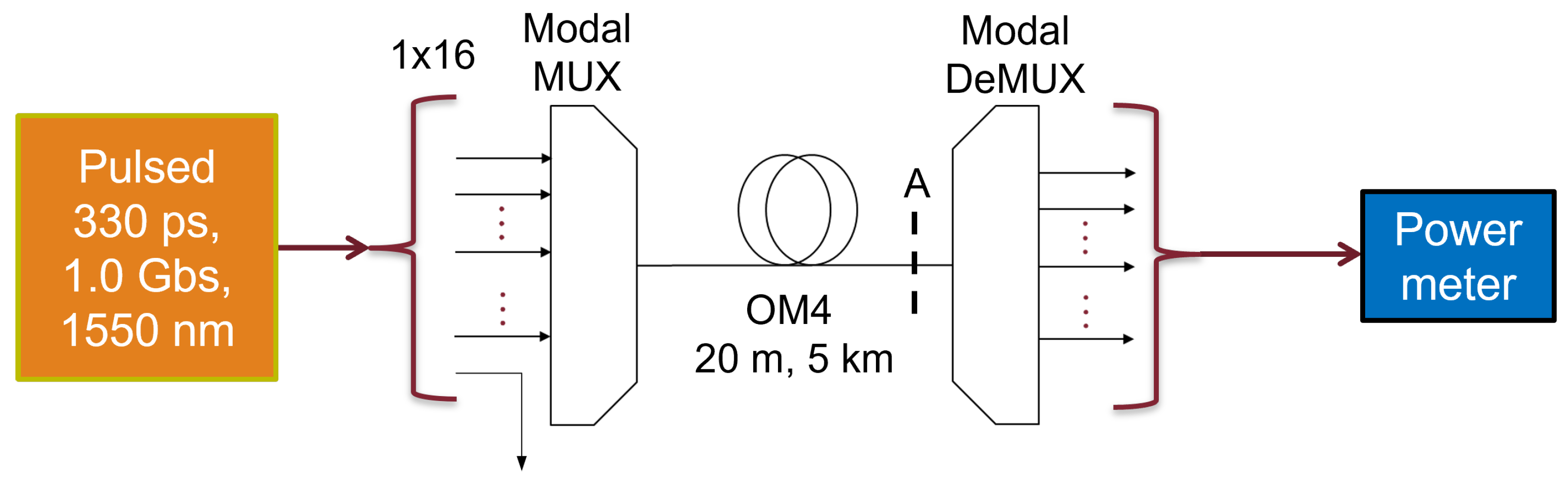

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiments

2.2. Numerical Model for GNLSE

2.3. Numerical Model for Power Flow Equations

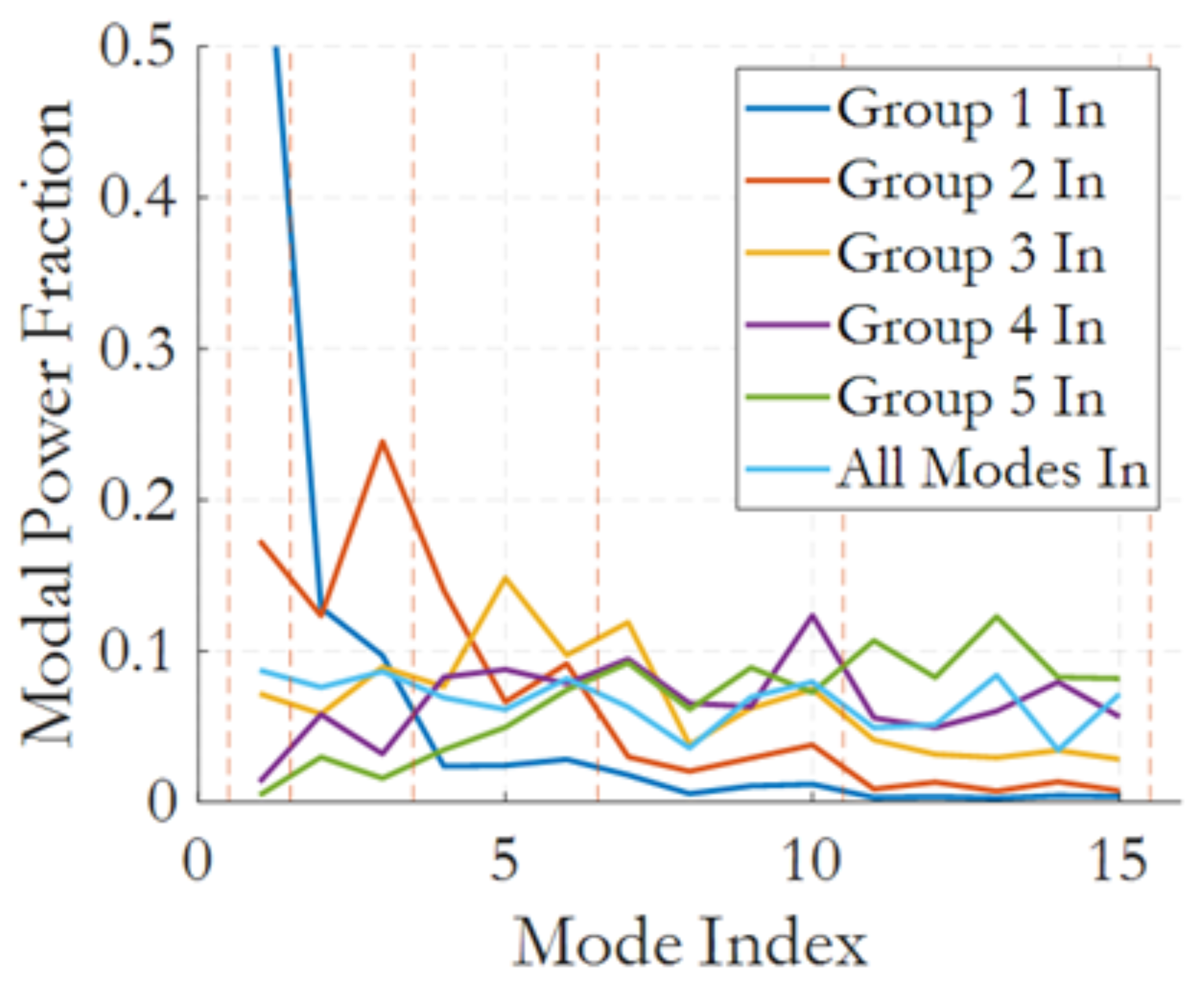

3. Results

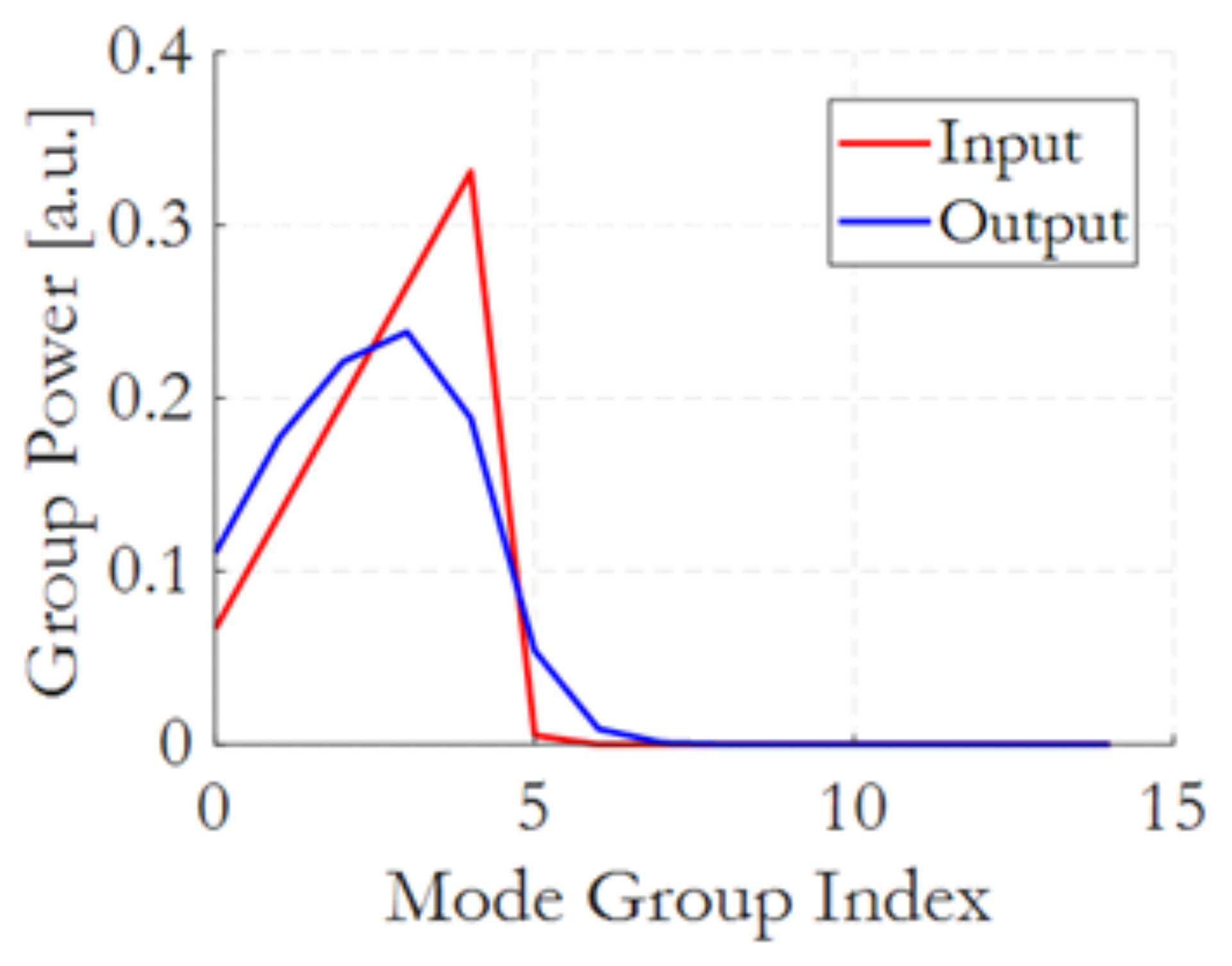

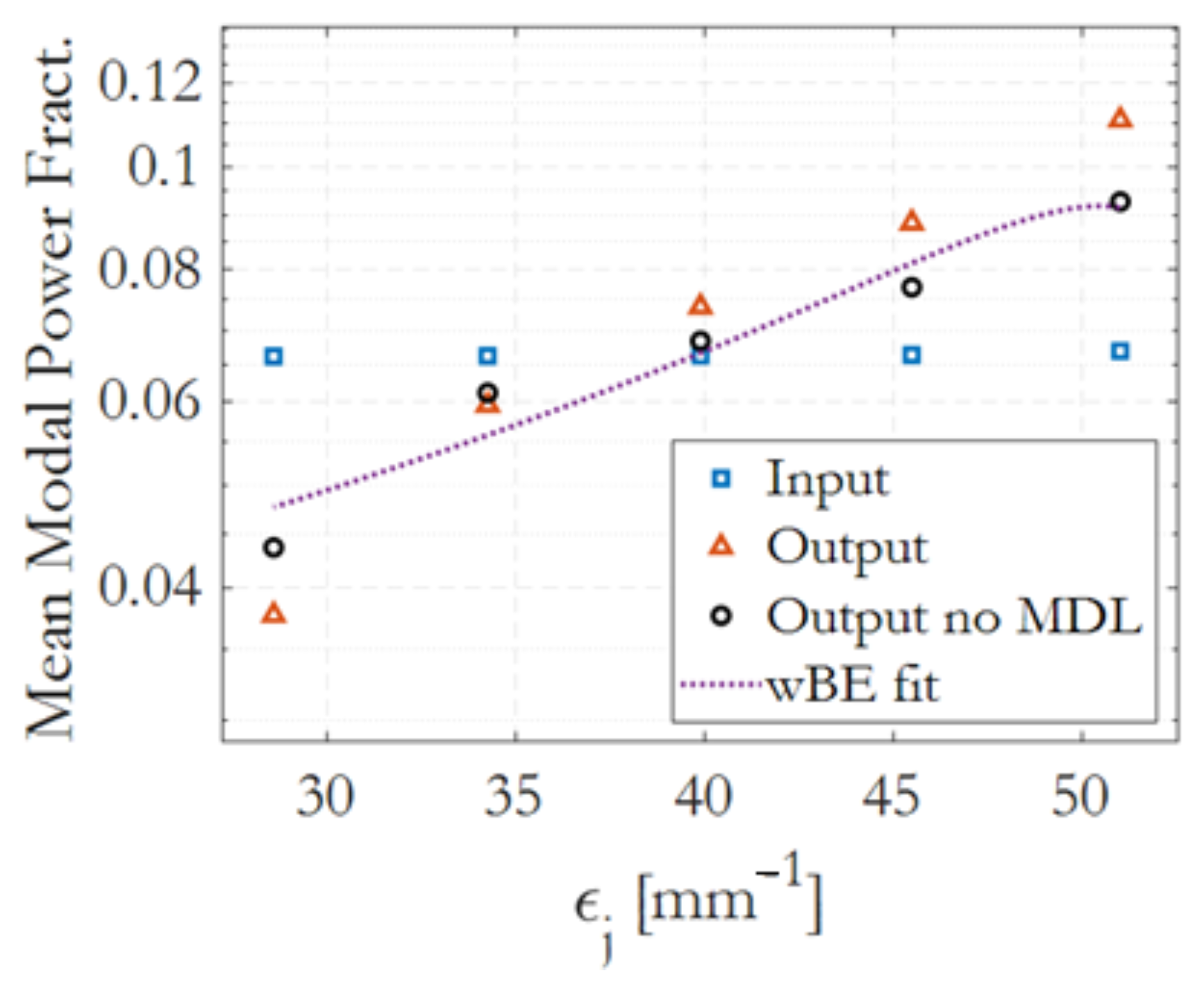

3.1. Linear Regime Experiment

3.2. Linear Regime Simulation

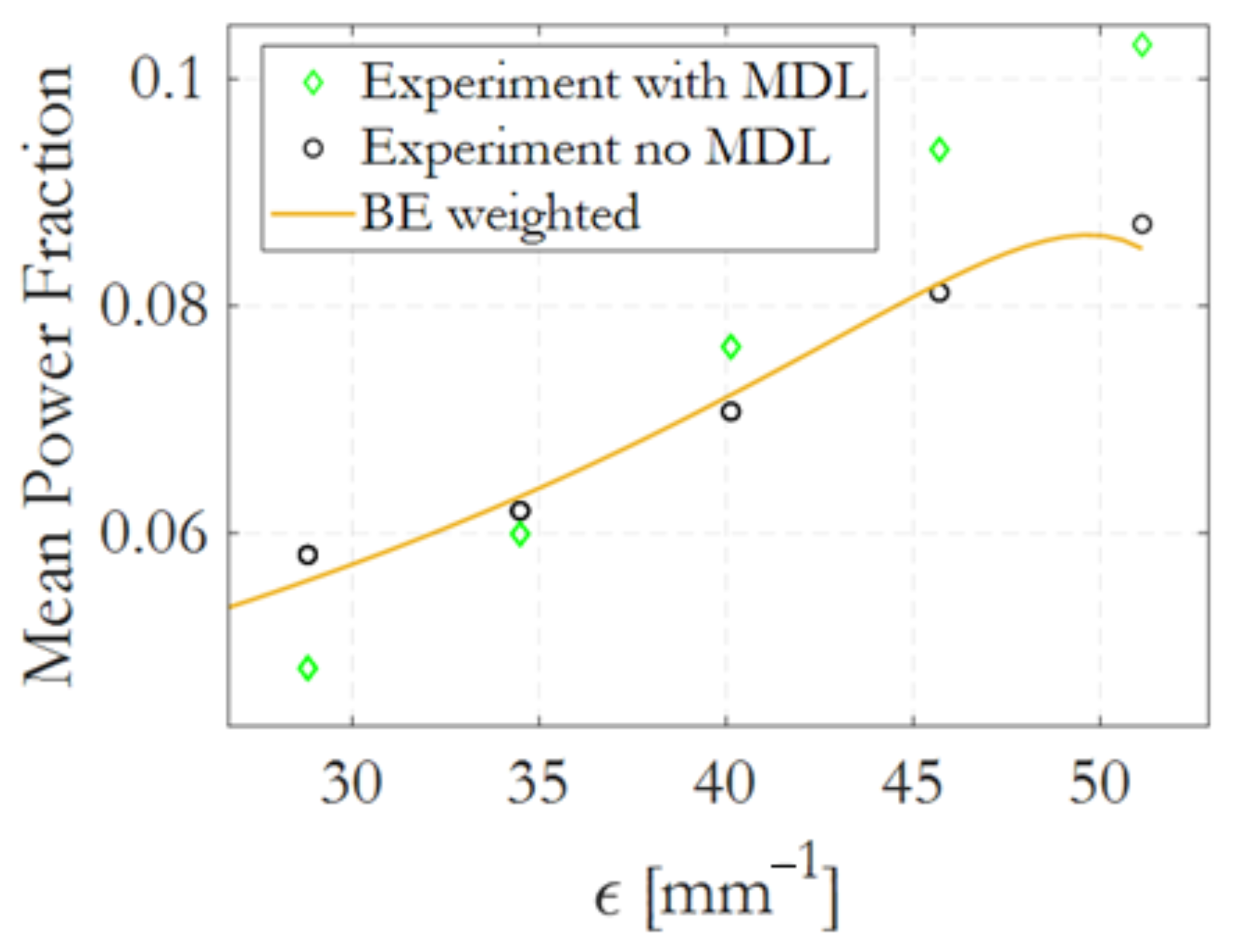

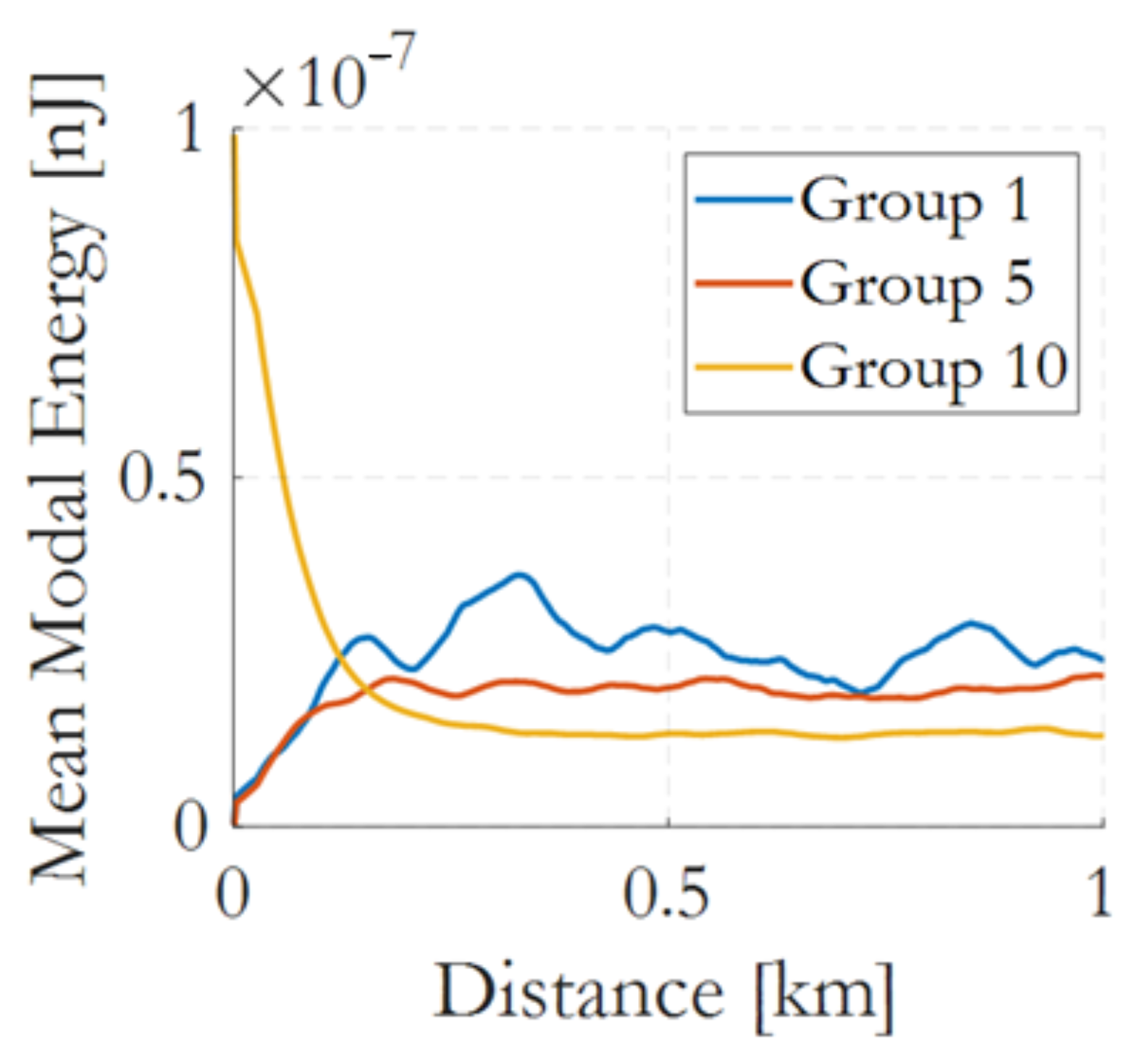

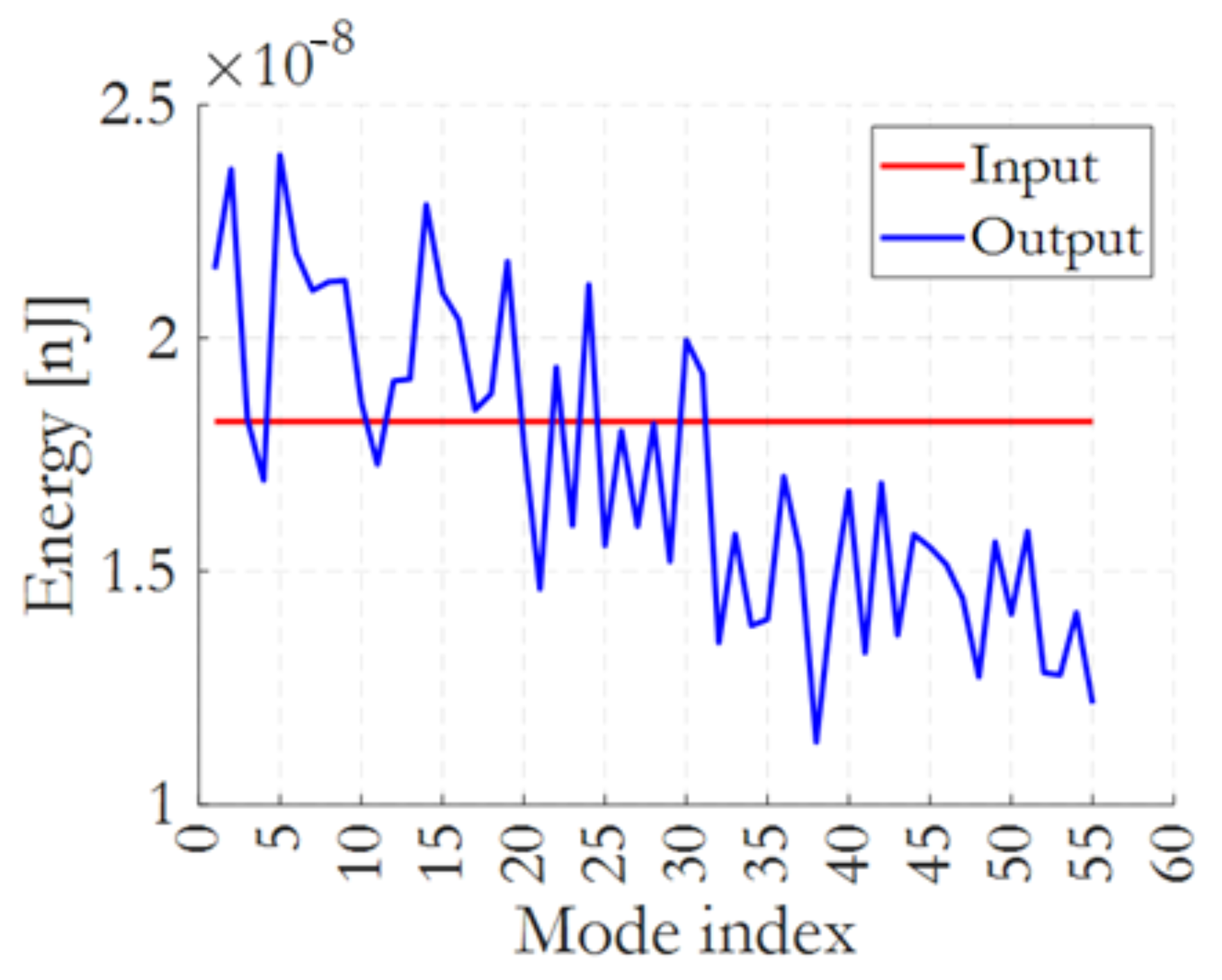

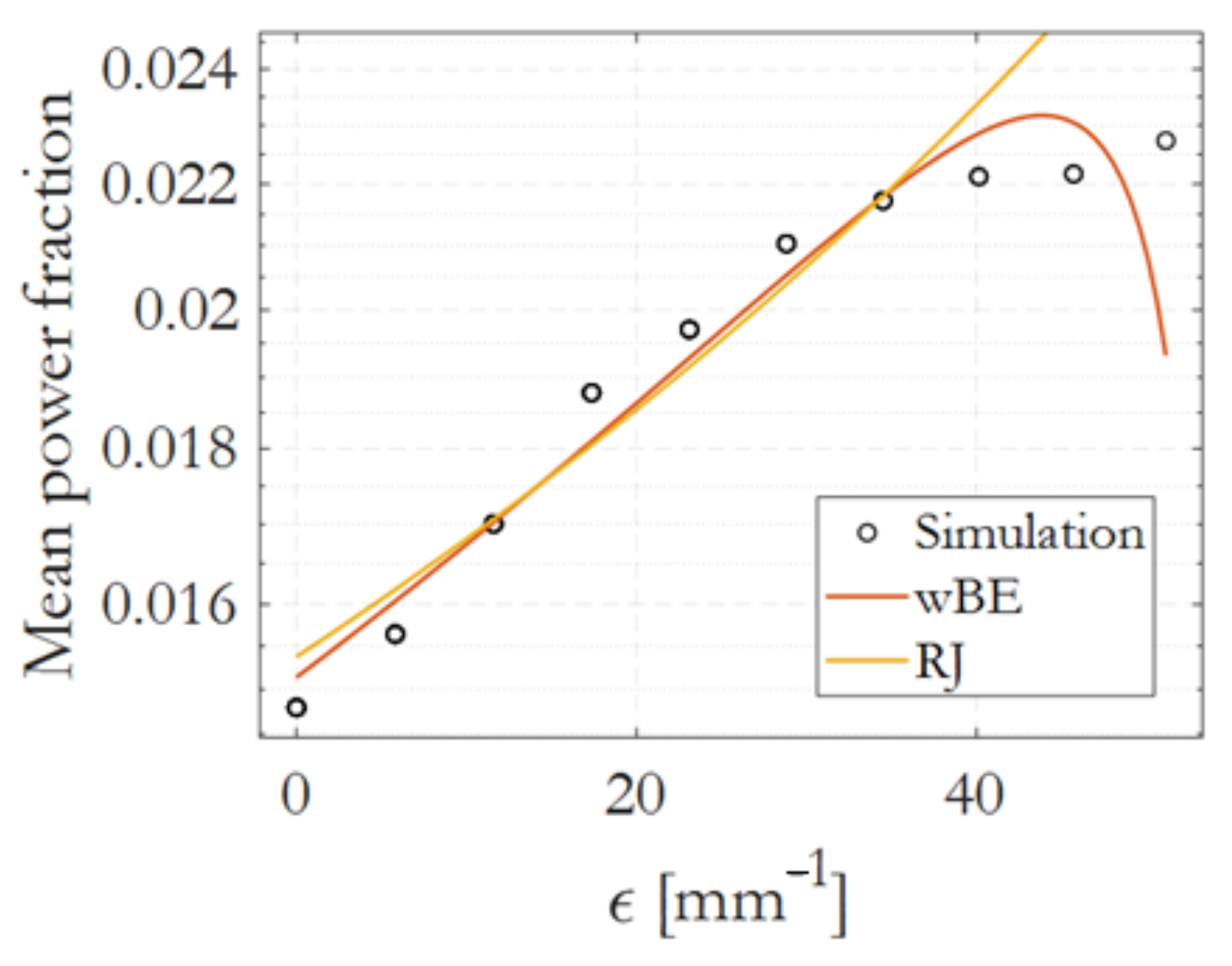

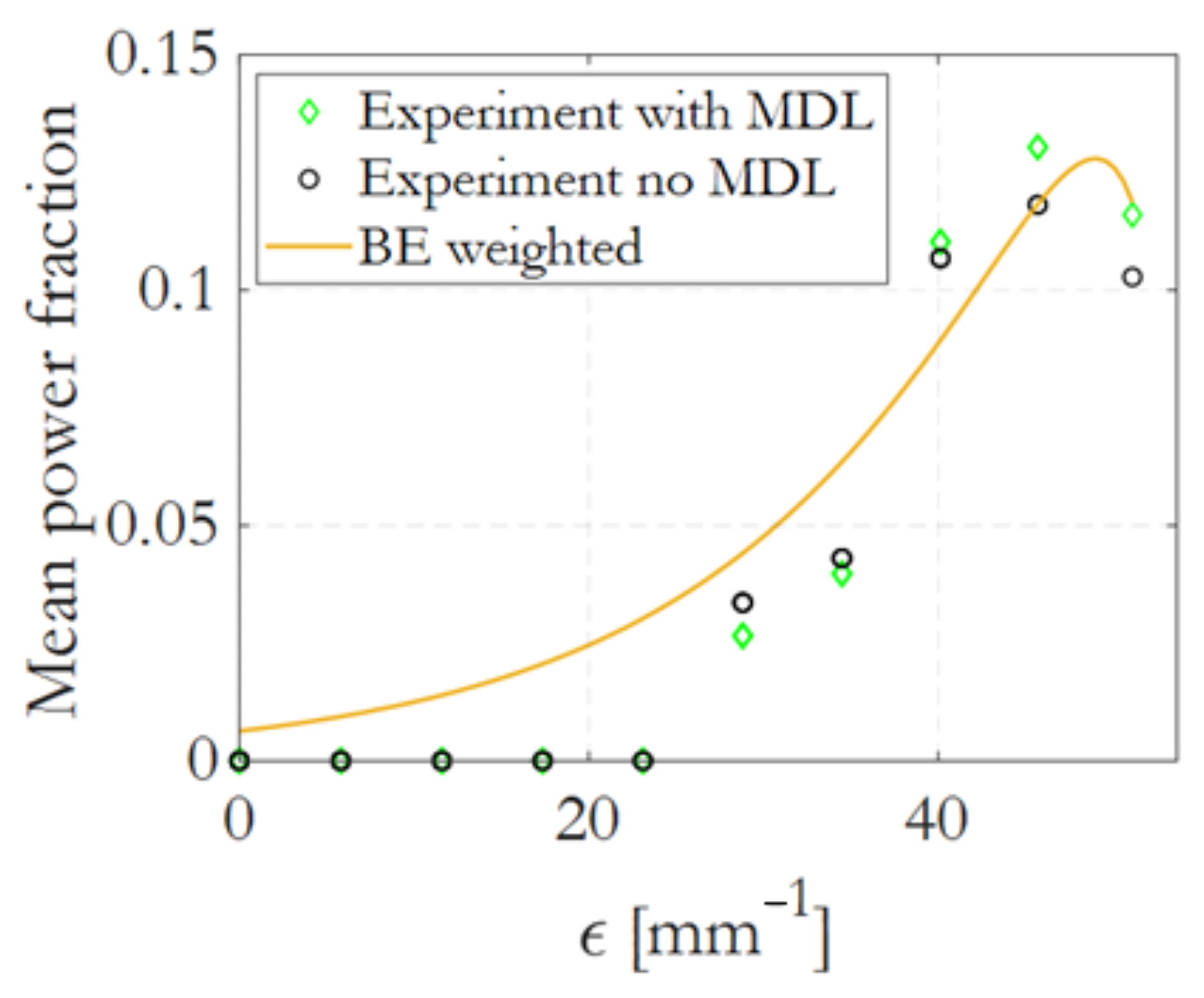

3.3. Power Flow Simulation

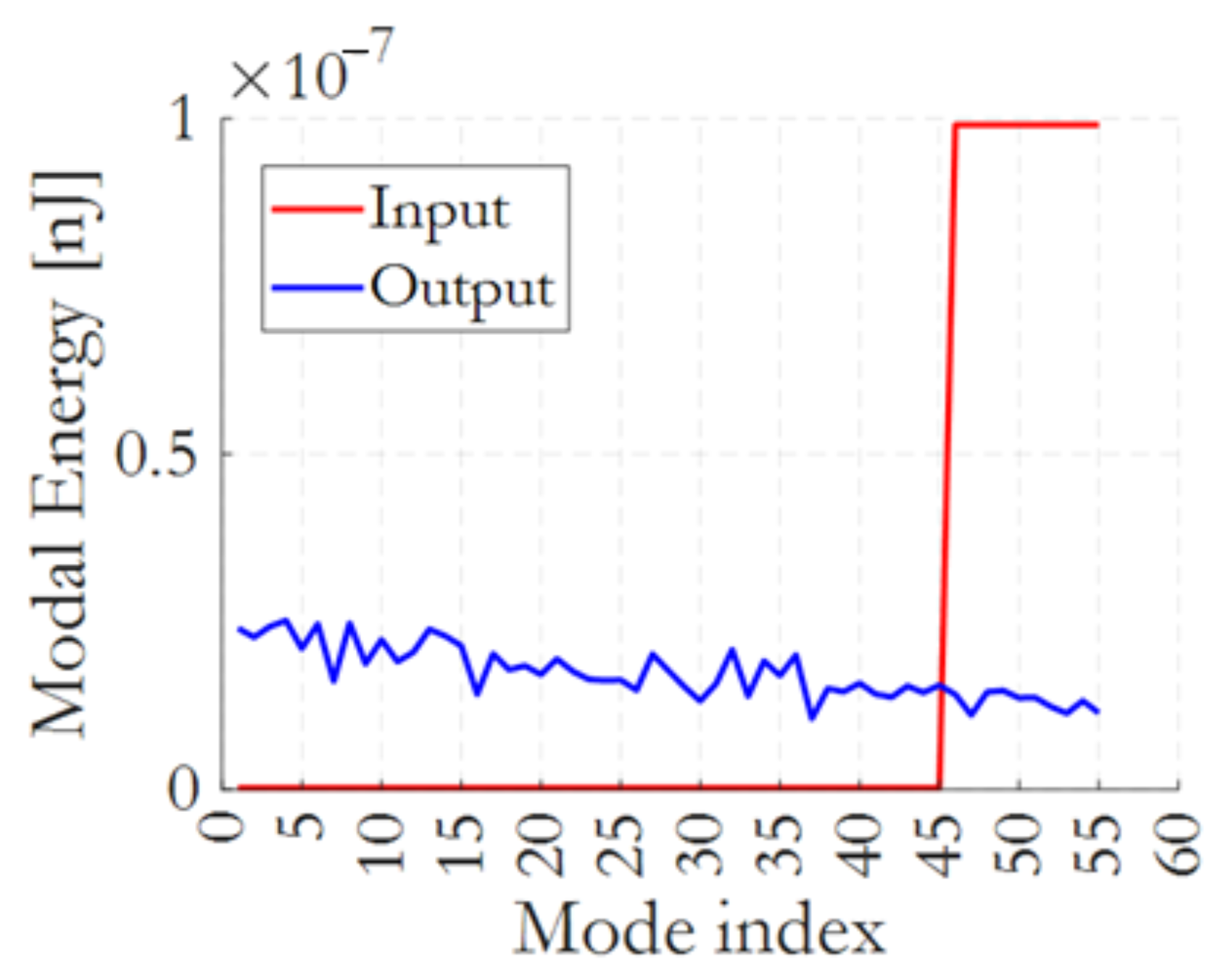

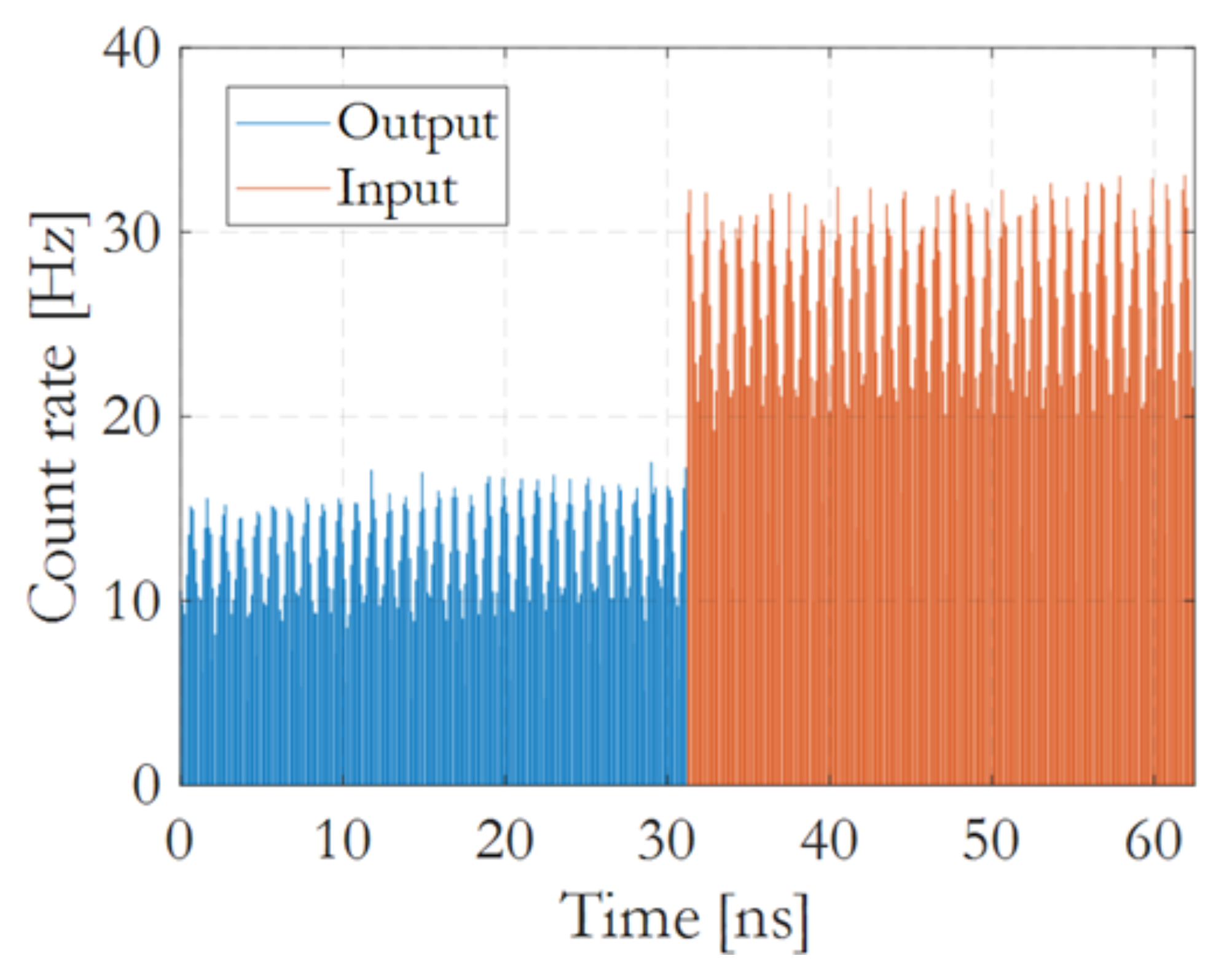

3.4. Quantum Experiment

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gloge, D.; Marcatili, E.A.J. Multimode theory of graded-core fibers. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1973, 52, 1563–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, A. Self-confinement of multimode optical pulse in a glass fiber. Opt. Lett. 1980, 5, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inao, S.; Sato, T.; Hondo, H.; Ogai, M.; Sentsui, S.; Otake, A.; Yoshizaki, K.; Ishihara, K.; Uchida, N. High density multicore-fiber cable. Proc. Int. Wire Cable Symp. 1979, 28, 370–384. [Google Scholar]

- Noordegraaf, D.; Skovgaard, P.M.W.; Nielsen, M.D.; Bland-Hawthorn, J. Efficient multi-mode to single-mode coupling in a photonic lantern. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 1988–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, G.P. Physics and Engineering of Graded-Index Media; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Essiambre, R.J.; Kramer, G.; Winzer, P.J.; Foschini, G.J.; Goebel, B. Capacity Limits of Optical Fiber Networks. J. Light. Technol. 2010, 28, 662–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzer, P.J.; Neilson, D.T.; Chraplyvy, A.R. Fiber-optic transmission and networking: The previous 20 and the next 20 years. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 24190–24239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.J.; Fini, J.M.; Nelson, L.E. Space-division multiplexing in optical fibres. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloge, D. Optical power flow in multimode fibers. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1972, 51, 1767–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savović, S.; Simović, A.R.; Drljaća, B.; Djordjevich, A.; Stepniak, G.; Bunge, C.A.; Bajić, J.S. Power Flow in Graded-Index Plastic Optical Fibers. J. Light. Technol. 2019, 37, 4985–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.P.; Kahn, J.M. Linear Propagation Effects in Mode-Division Multiplexing Systems. J. Light. Technol. 2014, 32, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, M.; Baudin, K.; Gervaziev, M.; Fusaro, A.; Picozzi, A.; Garnier, J.; Millot, G.; Kharenko, D.; Podivilov, E.; Babin, S.; et al. Wave turbulence, thermalization and multimode locking in optical fibers. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2025, 481, 134758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, N.; Baudin, K.; Fusaro, A.; Millot, G.; Picozzi, A.; Garnier, J. Interplay of Thermalization and Strong Disorder: Wave Turbulence Theory, Numerical Simulations, and Experiments in Multimode Optical Fibers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 129, 063901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Barbosa, F.A.; Ferreira, F.M. Modal Dynamics for Space-Division Multiplexing in Multi-Mode Fibers. J. Light. Technol. 2024, 42, 3695–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, F.; Horak, P. Description of ultrashort pulse propagation in multimode optical fibers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2008, 25, 1645–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.G.; Ziegler, Z.M.; Lushnikov, P.M.; Zhu, Z.; Eftekhar, M.A.; Christodoulides, D.N.; Wise, F.W. Multimode nonlinear fiber optics: Massively parallel numerical solver, tutorial, and outlook. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2018, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, S.; Essiambre, R.J.; Agrawal, G.P. Nonlinear Propagation in Multimode and Multicore Fibers: Generalization of the Manakov Equations. J. Light. Technol. 2013, 31, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloge, D. Bending Loss in Multimode Fibers with Graded and Ungraded Core Index. Appl. Opt. 1972, 11, 2506–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labroille, G.; Barré, N.; Pinel, O.; Denolle, B.; Lenglé, K.; Garcia, L.; Jaffrès, L.; Jian, P.; Morizur, J.F. Characterization and applications of spatial mode multiplexers based on Multi-Plane Light Conversion. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2017, 35, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitelli, M. A New Thermodynamic Approach to Multimode Fiber Self-cleaning and Soliton Condensation. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, 19, 2400714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitelli, M. A Thermodynamic Approach to Linear and Quantum Cross-Talk in Multimode Fiber Systems. J. Light. Technol. 2025, 43, 3974–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolen, R.H.; Tomlinson, W.J.; Haus, H.A.; Gordon, J.P. Raman response function of silica-core fibers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 1989, 6, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.O.; Hassan, A.U.; Christodoulides, D.N. Thermodynamic theory of highly multimoded nonlinear optical systems. Nat. Photonics 2019, 13, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savović, S.; Djordjevich, A. New method for calculating the coupling coefficient in graded index optical fibers. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 101, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zitelli, M. Non-Uniform Modal Power Distribution Caused by Disorder in Multimode Fibers. Photonics 2026, 13, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020129

Zitelli M. Non-Uniform Modal Power Distribution Caused by Disorder in Multimode Fibers. Photonics. 2026; 13(2):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020129

Chicago/Turabian StyleZitelli, Mario. 2026. "Non-Uniform Modal Power Distribution Caused by Disorder in Multimode Fibers" Photonics 13, no. 2: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020129

APA StyleZitelli, M. (2026). Non-Uniform Modal Power Distribution Caused by Disorder in Multimode Fibers. Photonics, 13(2), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13020129