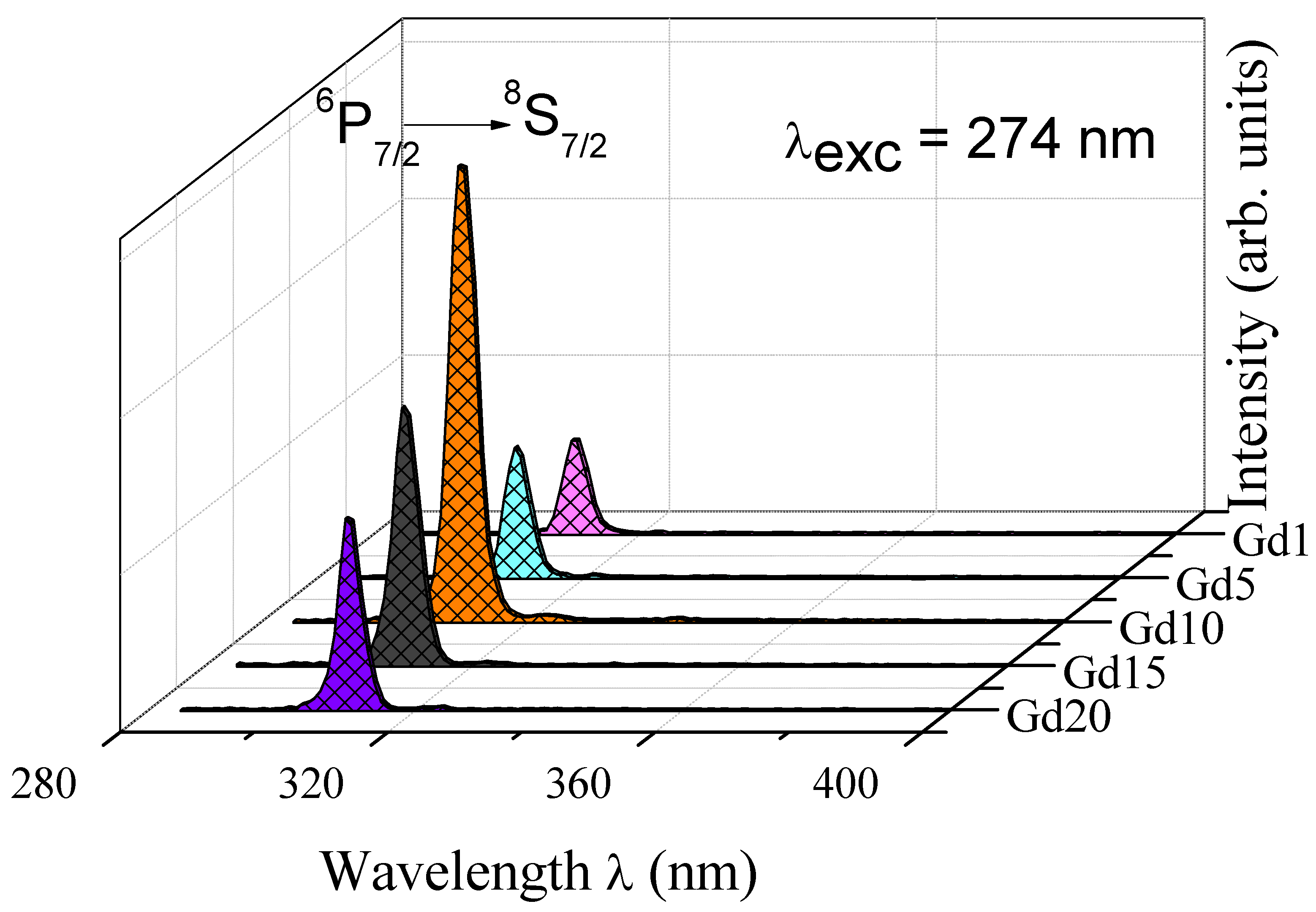

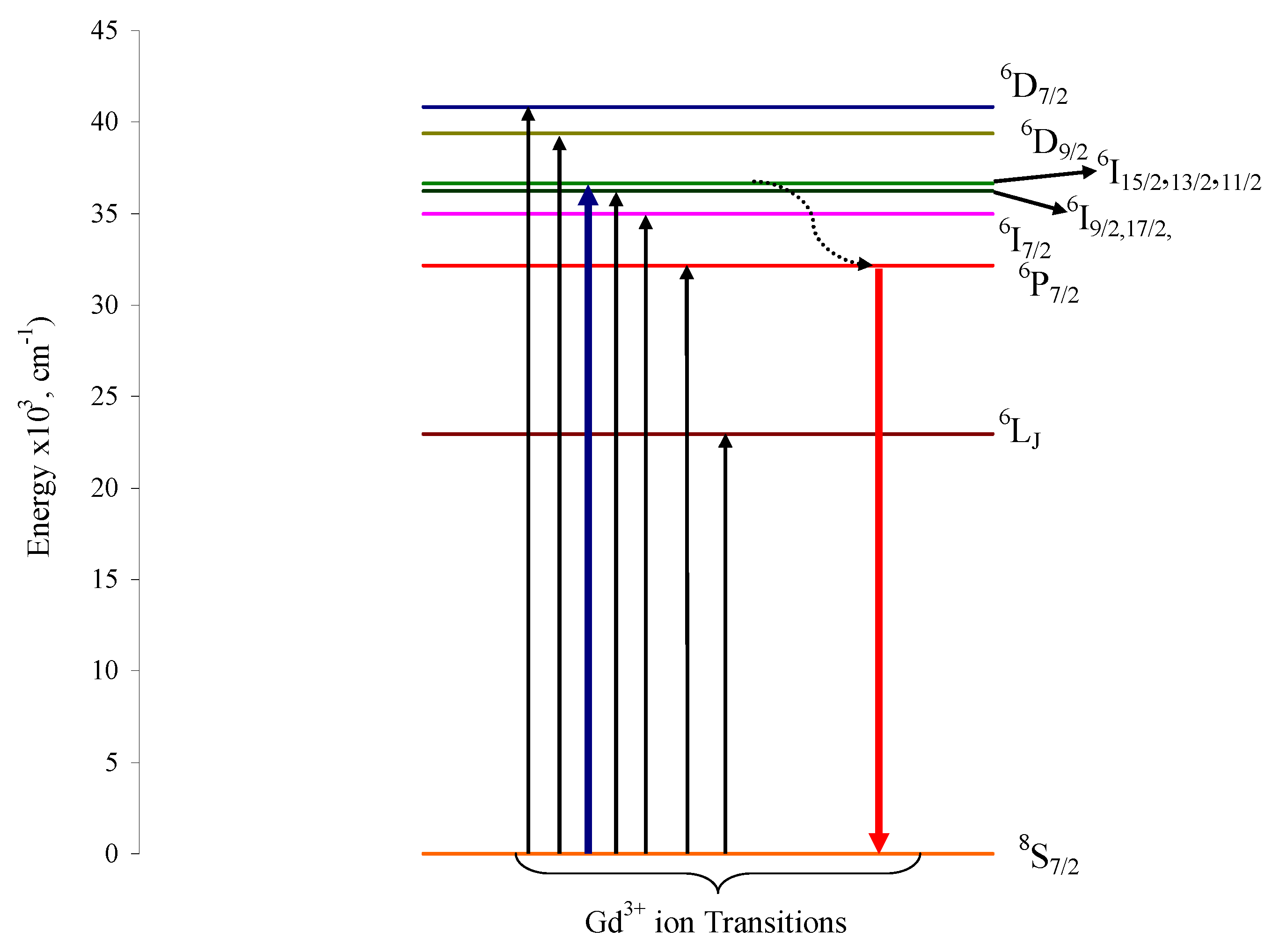

Enhanced 311 nm (NB-UVB) Emission in Gd2O3-Doped Pb3O4-Sb2O3-B2O3-Bi2O3 Glasses: A Promising Platform for Photonic and Medical Phototherapy Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

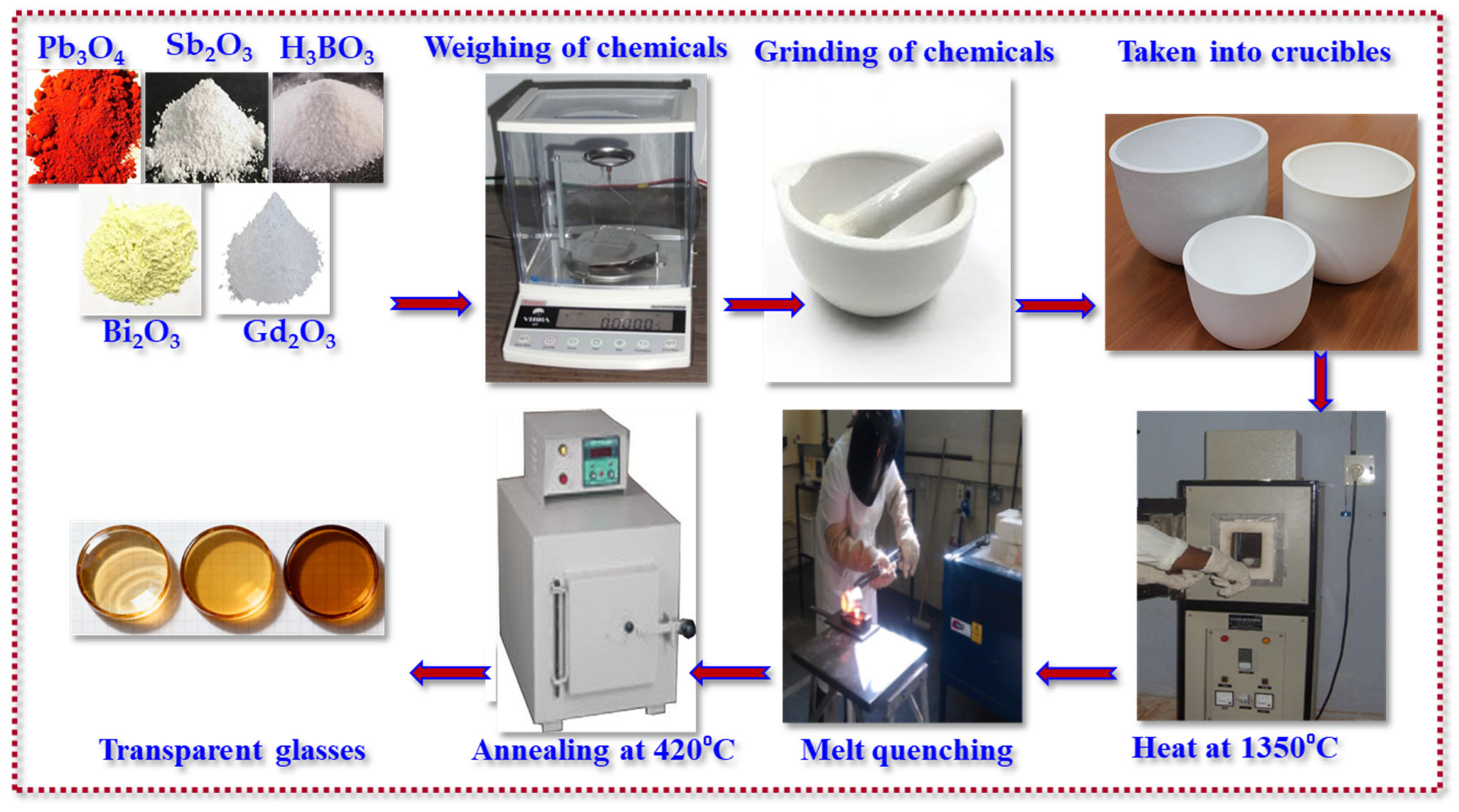

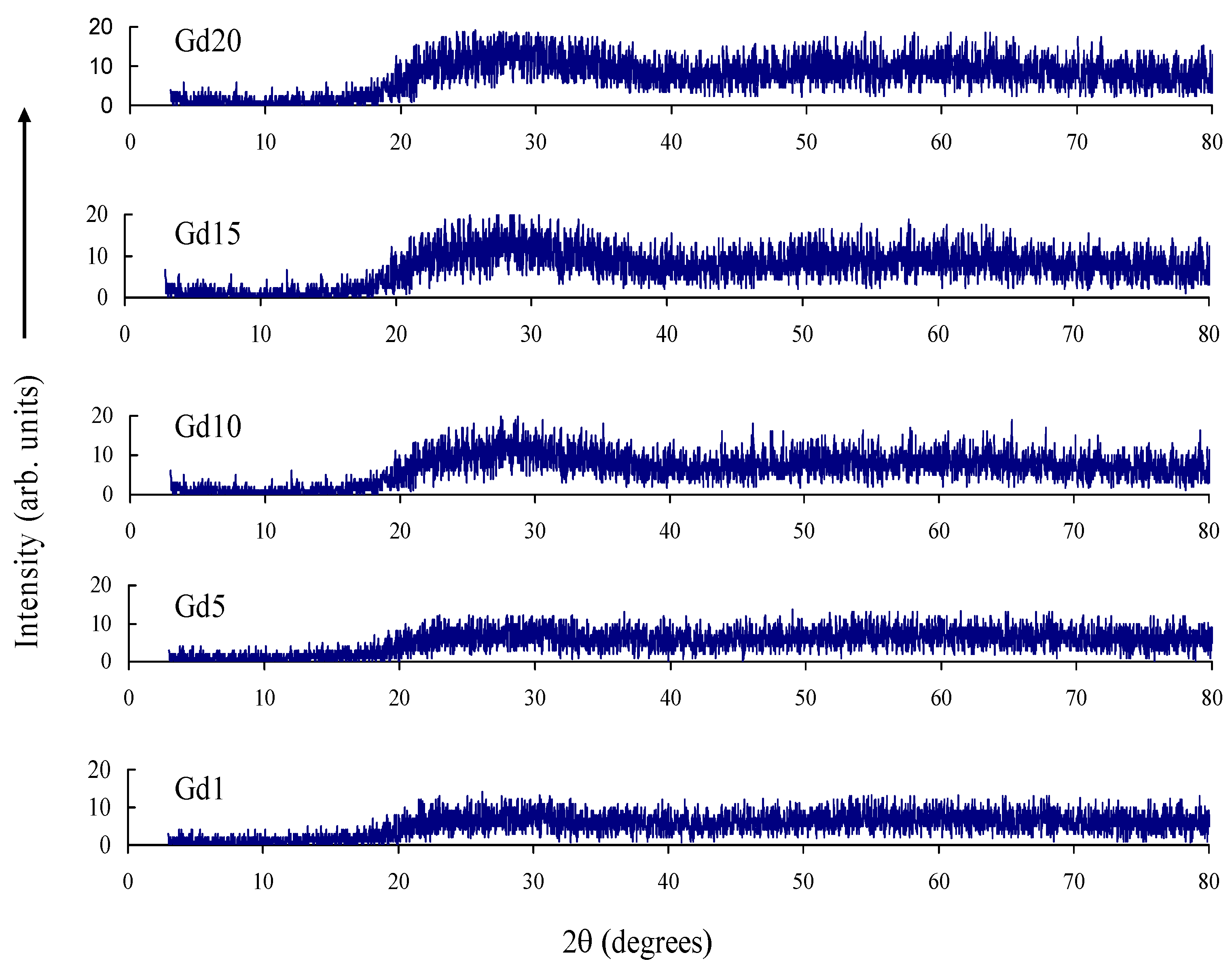

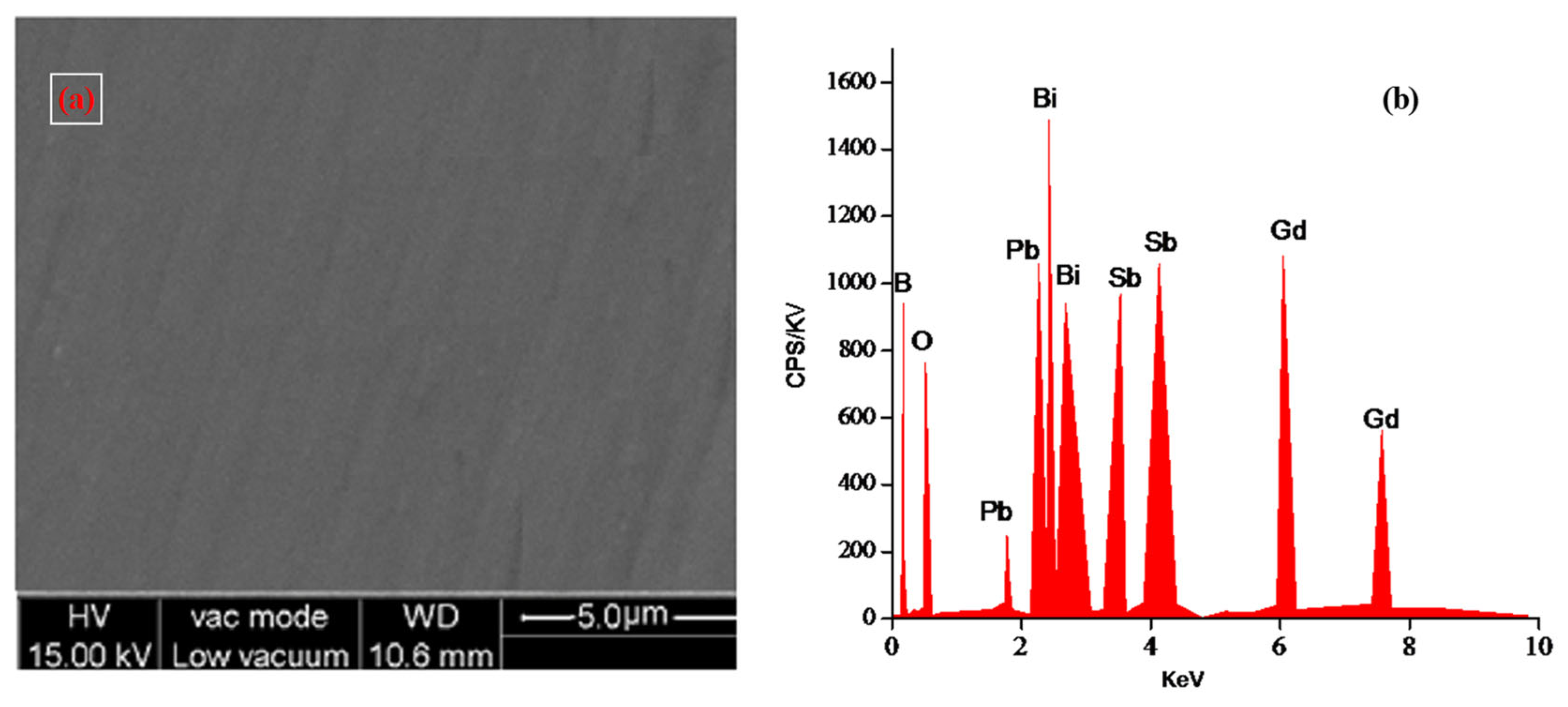

2. Experimental

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, V.; Swapna, K.; Kaur, S.; Rao, A.S.; Rao, J.L. Narrow-Band UVB-Emitting Gd-Doped SrY2O4 Phosphors. J. Electron. Mater. 2020, 49, 3025–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, L. Exploring Gd3+-activated calcium-based host materials for phototherapy lamps: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayalakshmi, L.; Kumar, K.N.; Baek, J.D. Narrow-band UVB emission from non-cytotoxic Gd3+-activated glasses for phototherapy lamps and UV-LED applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 11938–11945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Lv, X.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, L.; Liang, Y. A narrowband ultraviolet-B-emitting LiCaPO4:Gd3+ phosphor with super-long persistent luminescence for over 100 h. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 8314–8323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Shan, X.; Chen, D.; Miao, S.; Shi, R.; Xie, F.; Wang, W. X-ray-Excited Long-Lasting Narrowband Ultraviolet-B Persistent Luminescence from Gd3+-Doped Sr2P2O7 Phosphor. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 20647–20656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Kner, P.A.; Pan, Z. Gd3+-activated narrowband ultraviolet-B persistent luminescence through persistent energy transfer. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 3499–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpana, T.; Gandhi, Y.; Sanyal, B.; Sudarsan, V.; Bragiel, P.; Piasecki, M.; Kumar, V.R.; Veeraiah, N. Influence of alumina on photoluminescence and thermoluminescence characteristics of Gd3+ doped barium borophosphate glasses. J. Lumin. 2016, 179, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Gong, X.; Zhang, C.G.; Gu, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, G.; Guo, W. Drilled-hole number effects on energy and acoustic emission characteristics of brittle coal. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 3892–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, G.; Wu, H.; Beshiwork, B.A.; Tian, D.; Zhu, S.; Yang, Y.; Lu, X.; Ding, Y.; Ling, Y.; et al. A high-entropy perovskite cathode for solid oxide fuel cells. J. Alloy. Compd. 2021, 872, 159633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walo, M.; Przybytniak, G.; Sadło, J. EPR studies of gamma irradiated poly (ether-urethane)s. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2020, 171, 108669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Qin, J.; Dong, B.; Pan, S. The structural–magnetic properties relationship of amorphous pure Fe revealed by the minimum coordination polyhedron. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2019, 513, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madshal, M.A.; Abdelghany, A.M.; Abdelghany, M.I.; El-Damrawi, G. Biocompatible borate glasses doped with Gd2O3 for biomedical applications. Eur. Phy. J. Plus. 2022, 137, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Sarumaha, C.S.; Angnanon, A.; Khan, I.; Shoaib, M.; Khattak, S.A.; Mukamil, S.; Kothan, S.; Shah, S.K.; Wabaidur, S.M.; et al. Gd2O3-modulated borate glass for the enhancement of near-infrared emission via energy transfer from Gd3+ to Nd3+. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 16501–16509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Rai, V.K. Effect of the Addition of Pb3O4 and TiO2 on the Optical Properties of Er3+/Yb3+: TeO2–WO3 Glasses. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 16280–16291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soraya, M.M.; Ahmed, F.B.; Mahasen, M.M. Enhancing the physical, optical and shielding properties for ternary Sb2O3–B2O3–K2O glasses. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 22077–22091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasenko, V.; Nowagiel, M.; Wasiucionek, M.; Pietrzak, T.K. Stabilization of δ-like Bi2O3 Phase at Room Temperature in Binary and Ternary Bismuthate Glass Systems with Al2O3, SiO2, GeO2, and B2O3. Materials 2024, 17, 4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.J. Structural Chemistry of Glasses; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.R.C.; Hariprasad, D.; Jyothi, B.; Kumar, D.P.; Naresh, P.; Lakshmi, G.V.; Nagarjuna, M.; Kumar, V.R.; Gandhi, Y.; Veeraiah, N. Luminescence properties of Ho3+ ions inPb3O4- B2O3- P2O5- ZnO-AIIIx (AIIIx=Al2O3, Ga2O3, andIn2O3) glasses. Optik 2025, 328, 172315. [Google Scholar]

- Damdee, B.; Kaewnuam, E.; Kirdsiri, K.; Yamanoi, K.; Sarukura, N.; Shinohara, K.; Angnanon, A.; Intachai, N.; Kothan, S.; Kaewkhao, J. Concentration-dependent physical, optical, and photoluminescence features of Pr3+-doped borate glasses. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2024, 225, 112092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, K.; Chen, X.; Mao, J.; Pan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lv, P.; Wang, T.; Peng, H. Coupling effects in borosilicate glass leaching: A study on La/V doping. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 593, 155005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, K.; Chen, X.; Mao, J.; Pan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lv, P.; Wang, T.; Peng, H. Effect of tin ions on enhancing the intensity of narrow luminescenceline at 311 nm of Gd3+ ions in Li2O-PbO-P2O5 glass system. Opt. Mater. 2016, 57, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Marzouk, M.A.; Ali, I.S. Gamma irradiation Effects on Photoluminescence and Semiconducting Properties of Non-Conventional Heavy Metal Binary PbO–Bi2O3 Glasses. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AEl-Moneim, A.A.; Azooz, M.A.; Hashem, H.A.; Fayad, A.M.; Elwan, R.L. XRD, FTIR And Ultrasonic Investigations Of Cadmium Lead Bismuthate Glasses. Sci. Rep. 2023, 14, 12788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Batal, H.A.; El Batal, F.H.; Azooz, M.A.; Marzouk, M.A.; El Kheshen, A.A.; Ghoneim, N.A.; El Din, F.E.; Abdelghany, A.M. Comparative Shielding Behavior Of Binary PbO-B2O3 and Bi2O3-B2O3 Glasses with High Heavy Metal Oxide Contents Towards Gamma Irradiation Revealed By Collective Optical, FTIR And ESR Measurements. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 572, 121090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya Vamshi, B.; Vardhani, C.P.; Theerukachi, S. Synthesis, Characterization, and Optical Properties of Gadolinium Doped Bismuth Borate Glasses. J. Appl. Phy. 2025, 17, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, E.M.A.; Madbouly, A.M. Fabrication and characterization of different PbO borate glass systems as radiation-shielding containers. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsad, R.; Abdel-Aziz, A.M.; Ahmed, E.M.; Rammah, Y.; El-Agawany, F.; Shams, M. FT-IR, ultrasonic and dielectric characteristics of neodymium (III)/ erbium (III) lead-borate glasses: Experimental studies. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, S.; Dan, V.; Rada, M.; Culea, E. Gadolinium-environment in borate–tellurate glass ceramics studied by FTIR and EPR spectroscopy. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2009, 356, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toderaş, M.; Filip, S.; Ardelean, I. Structural study of the Fe2O3-B2O3-BaO glass system by FTIR spectroscopy. J. Adv. Mater. 2006, 8, 1121–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Ciceo-Lucacel, R.; Ardelean, I. FT-IR and Raman Study of Silver Lead Borate-Based Glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 2020–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madshal, M.A.; El-Damrawi, G.; Abdelghany, A.M.; Abdelghany, M.I. Structural studies and physical properties of Gd2O3-doped borate glass. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 14642–14653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyum, P.; Rittisut, W.; Wantana, N.; Ruangtaweep, Y.; Rujirawat, S.; Kamonsuangkasem, K.; Yimnirun, R.; Prasatkhetragarn, A.; Intachai, N.; Kothan, S.; et al. Structural and luminescence properties of transparent borate glass co-doped with Gd3+/Pr3+ for photonics application. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 32, 14642–14653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Watanabe, S.; Rao, T.G.; Lakshminarayana, G. Structural, paramagnetic centres and luminescence investigations of the UV radiation-emitting BaZrO3:Gd3+ perovskite ceramic prepared via sol-gel route. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2021, 264, 114971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wantana, N.; Kaewnuam, E.; Chanlek, N.; Kim, H.J.; Kaewkhao, J. Influence of Gd3+ on structural and luminescence properties of new Eu3+-doped borate glass for photonics material. Radat. Phy. Chem. 2023, 207, 110812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, A.N.; Sayyed, M.I.; Kamath, S.D. Impact of Gd2O3 Incorporation in Structural, Optical, Thermal, Mechanical, and Radiation Blocking Nature in HMO Boro-Tellurite Glasses. Eng. Proc. 2023, 55, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-K.; Bhat, A.A.; Watanabe, S.; Rao, T.; Singh, V. Unveiling the photoluminescence and electron paramagnetic resonance of Gd3+-Doped CaYAl3O7 phosphor emitting narrowband ultraviolet B radiation. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 10415–10422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.D.; Kumar, V.R.; Purnachand, N.; Sekhar, A.V.; Venkatramaiah, N.; Baskaran, G.S.; Veeraiah, N. Enhanced UVB 311 emission in Sb2O3–SiO2 glasses doped with Gd2O3 and tailored Pb3O4 content for potential phototherapy. Opt. Mater. 2024, 152, 115503. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Rai, D.; Rai, S. The effect of modifiers on the fluorescence and life-time of Gd3+ ions doped in borate glasses. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2001, 57, 2587–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galleani, G.; Lodi, T.A.; Conner, R.L.; Jacobsohn, L.G.; de Camargo, A.S. Photoluminescence and X-ray induced scintillation in Gd3+-Tb3+ co-doped fluoride-phosphate glasses, and derived glass-ceramics containing NaGdF4 nanocrystals. Opt. Mater. X 2024, 21, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, A.N.; Madivala, S.G.; Saraswathi, A.V.; Sayyed, M.I.; Rashad, M.; Kamath, S.D. Impact of Co-doping Eu3+ and Gd3+ in HMO-Based Glasses for Structural and Optical Properties and Radiation Shielding Enhancement. Luminescence 2025, 40, e70045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuks-Janczarek, I.; Miedzinski, R.; Kassab, L.R. Optical characterization and thermal analysis of rare earth-doped PbO-GeO2-G glasses embedded with gold nanoparticles. J. Alloy. Compd. 2024, 1002, 175221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramteke, D.; Gedam, R. Luminescence properties of Gd3+ containing glasses for ultra-violet (UV) light. J. Rare Earths 2013, 32, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagrai, M.; Unguresan, M.; Rada, S.; Zhang, J.; Pica, M.; Culea, E. Local structure in gadolinium-lead-borate glasses and glass-ceramics. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 2020, 546, 120259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Singh, K.; Thakur, S.; Kurudirek, M.; Rafiei, M.M. Structural investigations and nuclear radiation shielding ability of bismuth lithium antimony borate glasses. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 150, 109812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

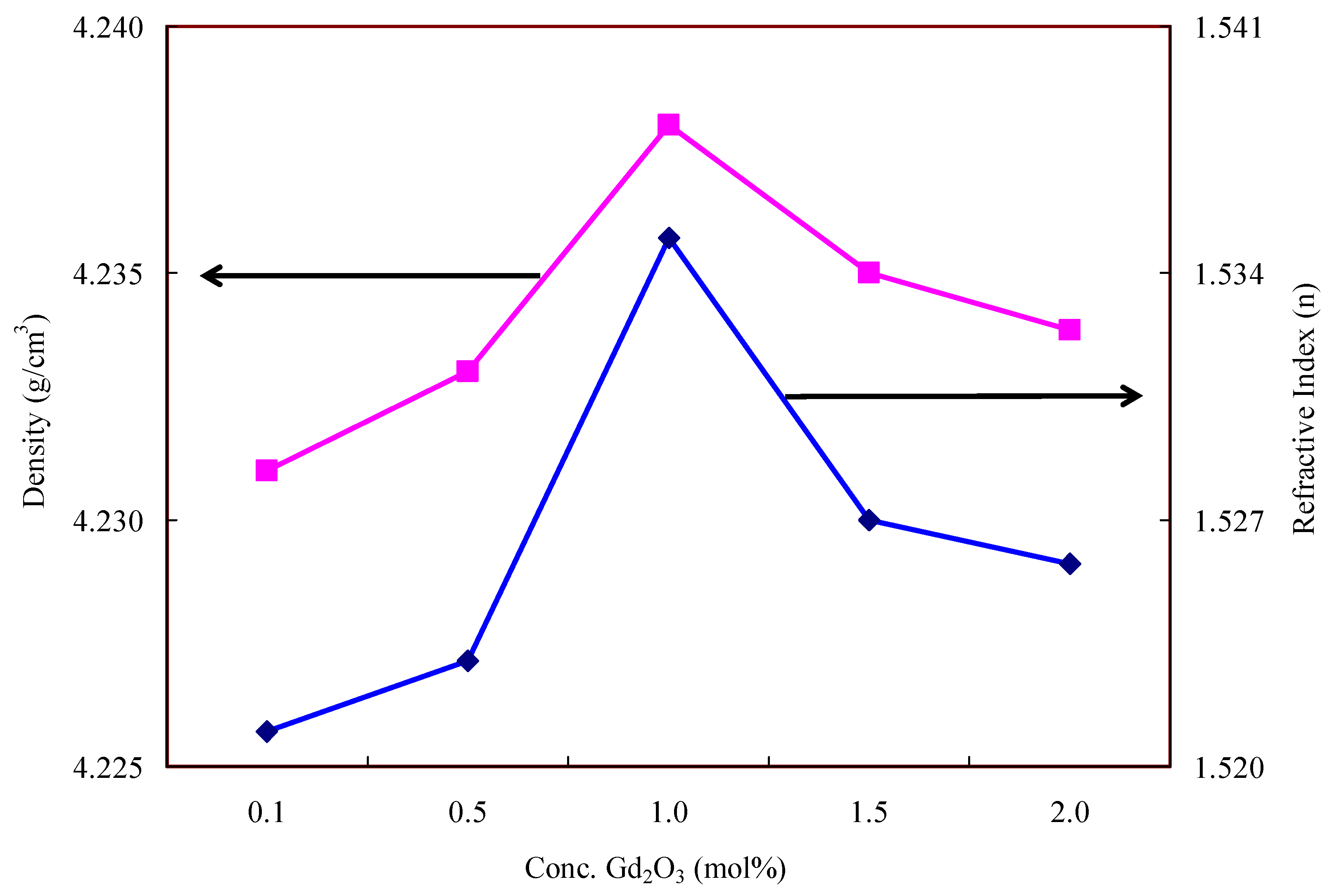

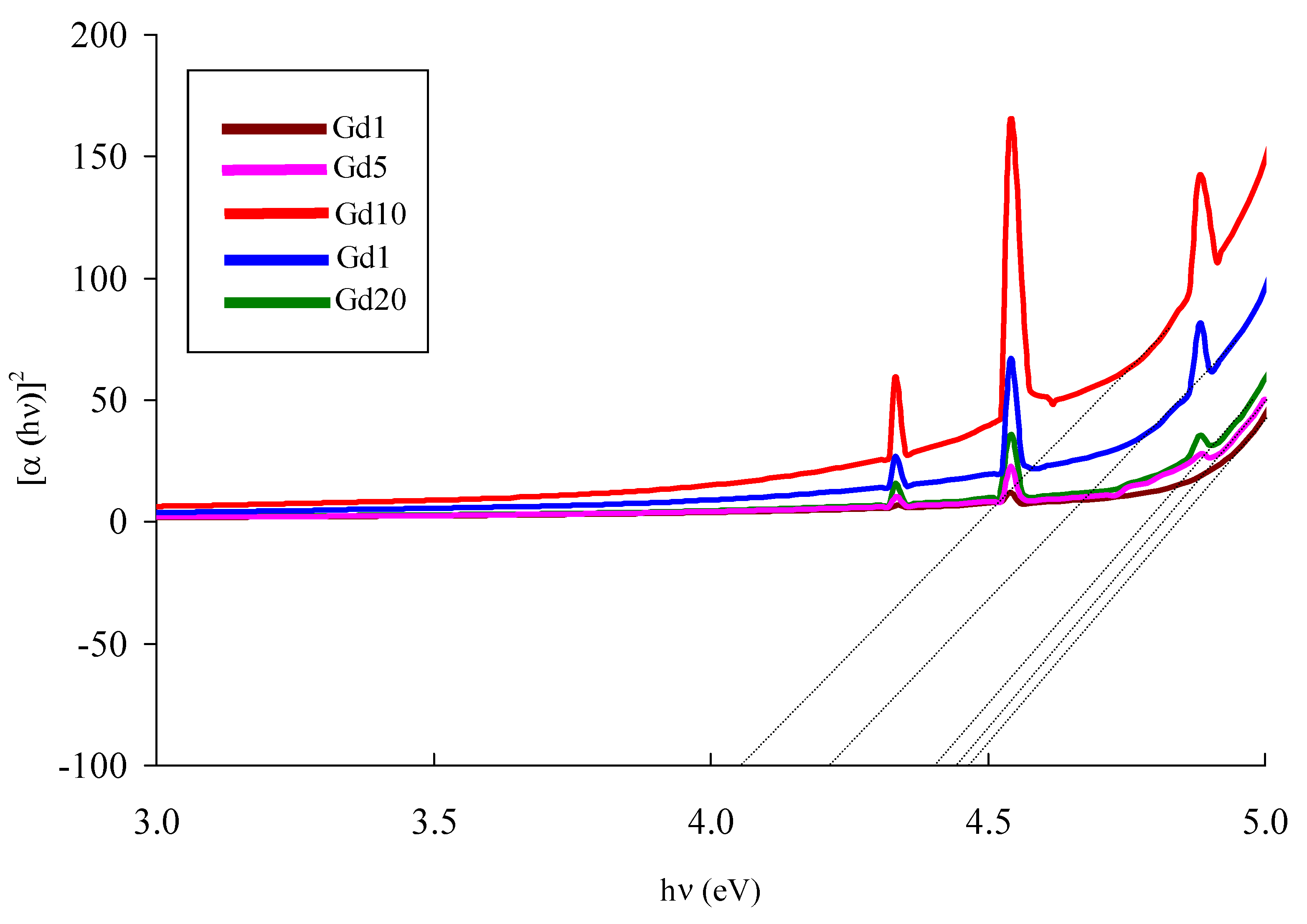

| Glass Sample | Density d (g/cm3) | Gd3+ Ion Conc. (Ni) (×1019/cm3) ± 0.001 | Gd3+ Inter Ionic Distance (Ri) nm ± 0.001 | Polaron Radius RP (nm) | Field Strength, Fi (×1014, cm−2) | Refractive Index, n | E0 (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gd1 | 4.231 | 1.184 | 4.387 | 0.918 | 0.346 | 1.521 | 4.45 |

| Gd5 | 4.233 | 1.297 | 2.569 | 1.586 | 0.325 | 1.523 | 4.43 |

| Gd10 | 4.238 | 1.474 | 2.043 | 1.972 | 0.231 | 1.535 | 4.05 |

| Gd15 | 4.235 | 1.752 | 2.387 | 2.254 | 0.177 | 1.527 | 4.20 |

| Gd20 | 4.233 | 2.323 | 2.426 | 2.477 | 0.146 | 1.525 | 4.40 |

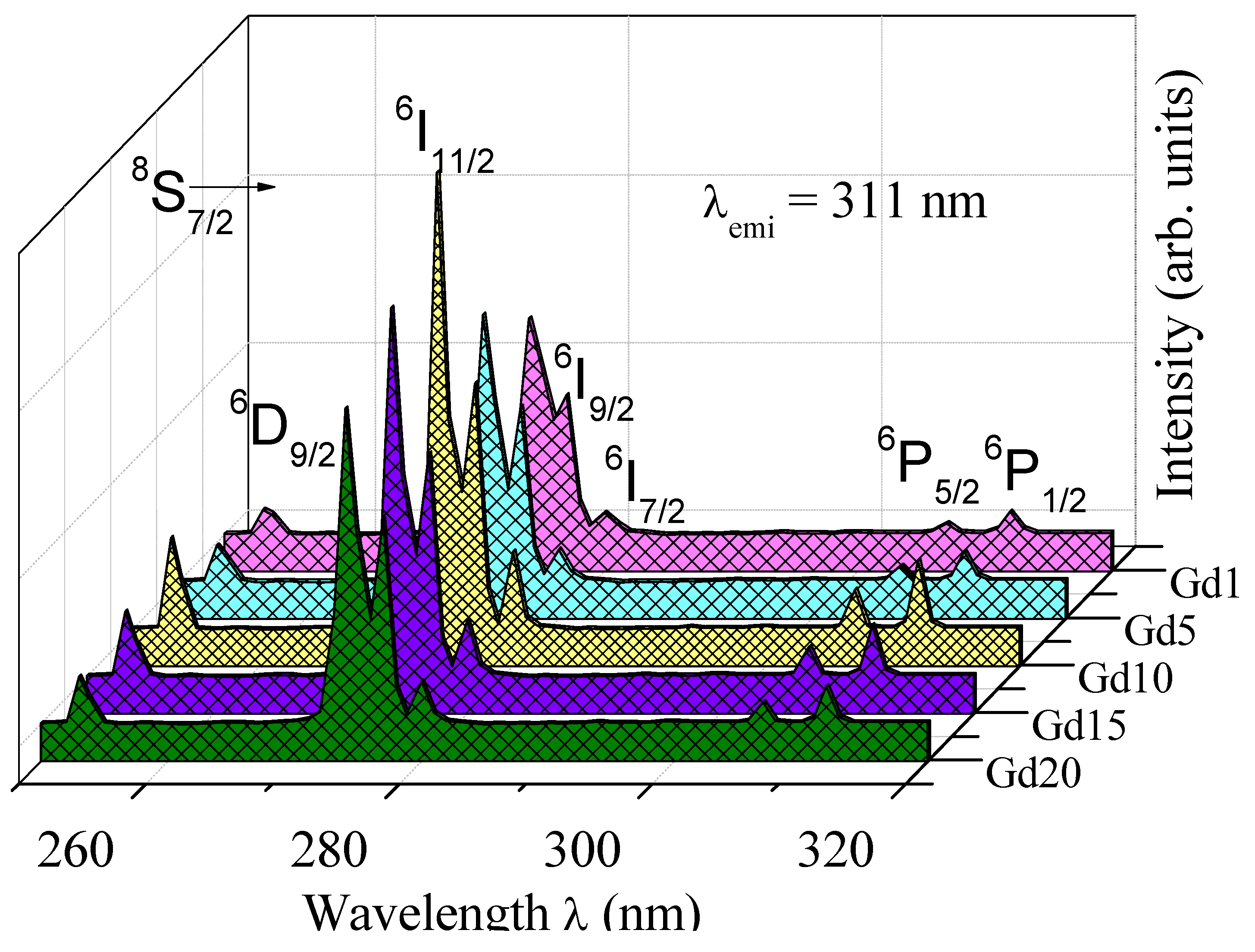

| Composition/Host Type | Gd3+ Conc. (mol%) | Emission λ (nm) | Lifetime τ (ns) | Optical Band Gap E0 (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb3O4–Sb2O3–B2O3–Bi2O3 (Present work) | 1.0 | 311 | 4.82 | 4.05 |

| Sb2O3–SiO2 with Pb3O4 tuning [37] | 1.0 | 311 | ~4–5 | ― |

| Borate glasses with modifiers [38] | Varied | 311–312 | ~3–5 | ~4.0–5.0 |

| Fluorophosphate/phosphate-based glasses [39] | Varied | 311 | ~4–8 | ~3.5–4.5 |

| Pb-containing HMO/lead-borate glasses [40] | 0.5–2.0 | 311–312 | ~3.5–6 | ~3.8–4.5 |

| Glass Sample | τ (ns) |

|---|---|

| Gd1 | 3.61 |

| Gd5 | 3.83 |

| Gd10 | 4.82 |

| Gd15 | 4.36 |

| Gd20 | 4.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, V.R.; Bhaskar, P.E.S.; Kumar, K.K.; Sujatha, V.; Nagalakshmi, V.; Geetha, V.; Vijayalakshmi, L.; Lim, J. Enhanced 311 nm (NB-UVB) Emission in Gd2O3-Doped Pb3O4-Sb2O3-B2O3-Bi2O3 Glasses: A Promising Platform for Photonic and Medical Phototherapy Applications. Photonics 2025, 12, 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121177

Kumar VR, Bhaskar PES, Kumar KK, Sujatha V, Nagalakshmi V, Geetha V, Vijayalakshmi L, Lim J. Enhanced 311 nm (NB-UVB) Emission in Gd2O3-Doped Pb3O4-Sb2O3-B2O3-Bi2O3 Glasses: A Promising Platform for Photonic and Medical Phototherapy Applications. Photonics. 2025; 12(12):1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121177

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Valluri Ravi, P. E. S. Bhaskar, K. Kiran Kumar, V. Sujatha, V. Nagalakshmi, V. Geetha, L. Vijayalakshmi, and Jiseok Lim. 2025. "Enhanced 311 nm (NB-UVB) Emission in Gd2O3-Doped Pb3O4-Sb2O3-B2O3-Bi2O3 Glasses: A Promising Platform for Photonic and Medical Phototherapy Applications" Photonics 12, no. 12: 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121177

APA StyleKumar, V. R., Bhaskar, P. E. S., Kumar, K. K., Sujatha, V., Nagalakshmi, V., Geetha, V., Vijayalakshmi, L., & Lim, J. (2025). Enhanced 311 nm (NB-UVB) Emission in Gd2O3-Doped Pb3O4-Sb2O3-B2O3-Bi2O3 Glasses: A Promising Platform for Photonic and Medical Phototherapy Applications. Photonics, 12(12), 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121177