Abstract

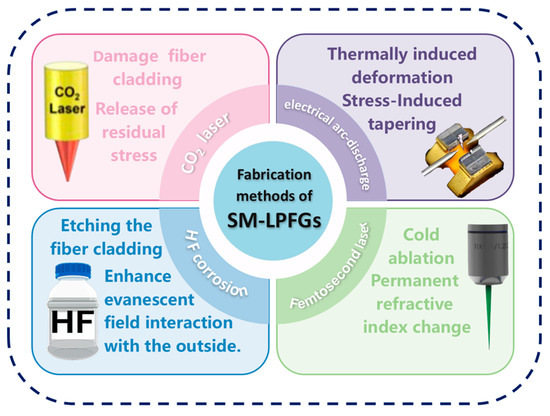

Structure-Modulated Long-Period Fiber Gratings (SM-LPFGs) represent an advancement in fiber optic sensor technology, moving beyond traditional photosensitivity-based fabrication to achieve enhanced performance through the direct physical modification of the geometry of the fiber. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the primary fabrication techniques enabling this approach, including CO2 laser inscription, femtosecond laser micromachining, electric-arc discharge, chemical etching, and fusion tapering. The central focus of this work is the elucidation of the definitive structure–performance relationship, systematically detailing how engineered geometries such as helical profiles, micro-tapers, and asymmetric grooves unlock novel sensing capabilities. We demonstrate how these specific structures are strategically designed to induce circular birefringence for torsion measurement, enhance evanescent field interaction for ultra-sensitive refractive index detection, and create localized stress concentrations for high-resolution strain and vector bending sensing. Furthermore, the review surveys the practical implementation of these sensors in critical application domains, including structural health monitoring, biomedical diagnostics, and environmental sensing. Finally, we conclude by summarizing key achievements and identifying promising future research directions, such as the development of hybrid fabrication processes, the integration of machine learning for advanced signal demodulation, and the path towards industrial-scale production.

1. Introduction

The accurate digital perception of the physical world serves as the foundational pillar for both the modern information age and the burgeoning field of artificial intelligence, imposing unprecedented performance requirements on sensing technologies. Within this context, optical fiber sensors have proven their efficacy, distinguished by intrinsic merits such as immunity to electromagnetic interference and a capacity for miniaturization [1]. Their value has been validated in a diverse range of demanding applications, including feedback for medical endoscopy [2,3], the monitoring of submarine cables [4], and three-dimensional [5] attitude sensing for intelligent robotics [6,7]. Among the various classes of fiber gratings, Long-Period Fiber Gratings (LPFGs) have garnered considerable research interest since their initial demonstration in the 1990s, primarily owing to their high sensitivity and versatile design flexibility [8]. Consequently, sensors based on LPFGs have demonstrated significant utility in a multitude of fields, including aerospace, structural health monitoring [9], oil pipeline inspection [10], and biomedical applications [11]. However, conventional LPFGs are predicated on the periodic modulation of the core refractive index. This fabrication paradigm presents significant challenges: the photosensitizing dopants, such as germanium and boron, required to facilitate this modulation invariably compromise the fiber’s mechanical strength. Furthermore, these devices suffer from significant temperature cross-sensitivity [12]. These inherent drawbacks hinder the efficient excitation of higher-order modes that are selectively sensitive to specific measurands, thereby imposing a fundamental limit on achievable sensitivity enhancements. Therefore, the development of novel LPFGs that simultaneously possess high sensitivity, robust immunity to temperature cross-talk, and superior mechanical integrity has emerged as a pivotal challenge confronting the research community [13].

This review synthesizes and categorizes a class of novel long-period fiber gratings (LPFGs) engineered through the modification of the external cladding morphology or geometry. We propose and define these devices as SM-LPFGs. In SM-LPFGs, the deliberately altered spatial configuration induces a more pronounced structural deformation in response to external environmental perturbations. This amplified deformation, in turn, results in a significantly larger shift in the grating’s resonant wavelength. This approach represents a paradigm shift from conventional LPFG fabrication, which primarily relies on the intrinsic photosensitivity of the fiber material. The fabrication strategy instead pivots to the active and structured modulation of the fiber’s physical geometry using precision processing techniques. By incorporating asymmetric geometric configurations such as grooves, micro-tapers, or helical structures, SM-LPFGs can (1) reshape the stress field on the fiber surface, transforming external forces into highly concentrated local stress and thereby enabling high-sensitivity mechanical sensing; (2) break the inherent cylindrical symmetry of the fiber, facilitating vectorial measurement capabilities; and (3) reduce the cladding dimension, which significantly enhances the interaction between the evanescent field and the surrounding medium. These structural innovations are instrumental in enhancing sensing sensitivity, imparting directional recognition capabilities to the LPFGs, and lowering their detection thresholds for various external parameters [14]. However, the structural designs of SM-LPFGs are exceptionally diverse, and consequently, their sensing performance varies widely. Despite the rapid advancements in LPFG research over the past decade, existing review articles have predominantly focused on specific sub-topics. These include comparative analyses of fabrication techniques like tapering [15], performance-oriented summaries for biomedical applications [16], and the rational structural optimization for embedded fiber sensors [17]. To date, a comprehensive review that systematically elucidates the fundamental “structure–performance relationship”—that is, how a specific physical geometry dictates the final sensing efficacy—is conspicuously absent. Therefore, this review aims to fill this gap by providing a novel perspective that systematically establishes the structure–performance correlations for SM-LPFGs. Through an in-depth analysis of the determinative influence of different structural designs on sensor performance, we categorize various SM-LPFG architectures according to the specific sensing modalities they enable. Our objective is to furnish a comprehensive guide that will empower researchers in the goal-oriented design and fabrication of next-generation SM-LPFGs.

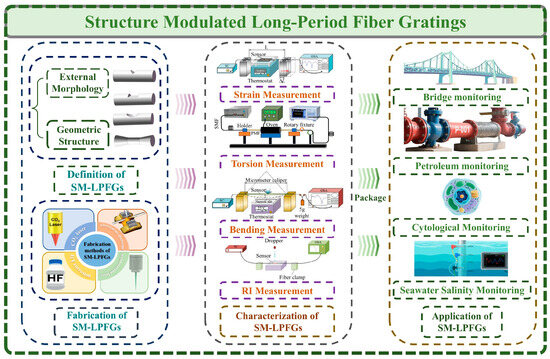

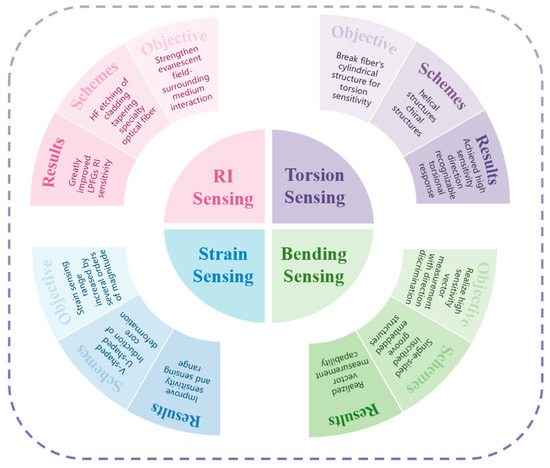

To provide a systematic overview of the research landscape for SM-LPFGs and to chart its future course, this review is structured into four main sections, as illustrated in Figure 1. The review commences with a systematic examination of the four principal fabrication techniques for SM-LPFGs: CO2 laser inscription, electric-arc discharge, chemical etching and femtosecond laser micromachining. We will conduct a thorough analysis of each method, evaluating their underlying principles for inducing physical deformation in the optical fiber, as well as their respective advantages and inherent limitations. Building upon this foundation, the discussion pivots to the four principal sensing applications: strain, torsion, bending, and refractive index. In this core section, we critically analyze how distinct physical modulations—such as D-shaped side-polishing, V-grooving, helical micro-channels, and induced core-distortion—are engineered to enhance sensing performance. A comparative analysis of various SM-LPFGs is presented, with a focus on key performance metrics including sensitivity, measurement range, and immunity to cross-sensitivity, thereby elucidating the causal link between specific structural modifications and the observed performance gains. We will further explore the nuanced relationship between specific structural designs and sensing characteristics, detailing the relative merits of different fiber types in strain and bending sensing applications and the physical principles that govern their behavior. Subsequently, the review will survey the burgeoning applications of these high-performance SM-LPFG sensors, showcasing their potential and highlighting recent advancements in critical domains such as structural health monitoring, biomedical sensing, and environmental monitoring [18,19]. Finally, this review provides a critical assessment of the current landscape and future development direction of SM-LPFGs.

Figure 1.

This review establishes the structure–performance relationship for SM-LPFGs: SM-LPFGs are enhanced by engineering the fiber’s physical geometry. By classifying fabrication techniques such as laser etching according to the distinct structures they impart, we establish the critical structure–performance relationship, elucidate this critical correlation and chart promising directions for future research.

2. Fabrication of SM-LPFGs

As passive in-fiber components, LPFGs operate on the principle of phase-matching between the fundamental core mode and a set of co-propagating cladding modes [2]. When this condition is satisfied, light at a specific resonant wavelength is efficiently coupled from the core to the cladding, which creates a distinct attenuation band in the transmission spectrum [8]. This phase-matching condition is given by:

The is the resonant wavelength, and are the effective refractive indices of the fundamental core mode and the cladding mode [8], respectively, and is the grating period. As light propagates through the fiber core, the specific wavelength that satisfies this phase-matching condition is coupled into a co-propagating cladding mode [13,20]. The sensing principle of an LPFG is intrinsically linked to this relationship. Any change in external physical parameters—such as strain, bending, torsion, surrounding refractive index, or temperature—will modulate the effective refractive indices of the core and cladding modes. This, in turn, alters the index difference, , thereby shifting the resonant wavelength . By establishing a quantitative relationship between the magnitude of this wavelength shift and the change in the measurand, precise measurement is achieved.

The temperature sensitivity of an LPFG is governed by the product of a waveguide dispersion factor and a material thermo-optic factor. For higher-order modes, the waveguide dispersion factor can undergo a sign change, leading to starkly different behaviors where modes exhibit either positive, negative, or near-zero temperature-induced wavelength shifts [13].

From a more fundamental physical perspective, the design philosophy of SM-LPFGs is rooted in the deliberate engineering of the coupling matrix within Coupled-Mode Theory (CMT). In an ideal, cylindrically symmetric LPFG, this matrix is highly sparse; the selection rules, dictated by modal field orthogonality, permit coupling exclusively between the fundamental core mode (LP01) and specific, cylindrically symmetric cladding modes (LP0m). The foundational purpose of structural modulation is to intentionally break this pristine symmetry, thereby “rewriting” the coupling matrix to populate it with new.

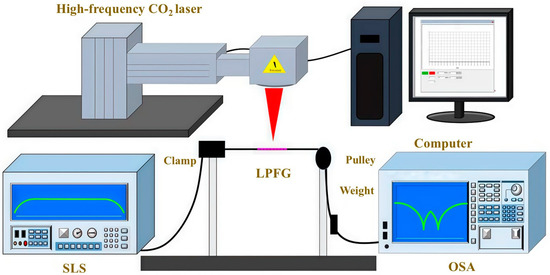

2.1. CO2 Laser Fabrication of SM-LPFGs

In a seminal work in 1998, Davis et al. [21] first demonstrated the feasibility of using low-frequency CO2 laser pulses for grating fabrication, establishing a paradigm independent of photochemical effects Figure 2. The technique leverages the localized thermal effects of the laser to induce residual stress relaxation and glass densification within a single-mode fiber (SMF), thereby achieving the requisite refractive index modulation. This approach circumvents the reliance on ultraviolet (UV) irradiation and has since been widely adopted for fabricating various types of SM-LPFGs.

Figure 2.

CO2 laser fabrication of SM-LPFGs.

Subsequently, Rao et al. [22] employed high-frequency CO2 laser pulses to enhance both the inscription efficiency and the modulation depth. Building on this, they introduced asymmetry by inscribing grooves, which induced localized stress concentrations. The resulting SM-LPFGs exhibited strain sensitivities markedly higher than their conventional counterparts, though temperature cross-sensitivity remained an issue [23]. With a more profound understanding of the underlying principles, researchers began to harness the laser for direct thermal shaping of the fiber, creating micro-tapers and helical structures to produce advanced SM-LPFGs and hybrid sensors for multi-parameter measurements [24]. SM-LPFGs fabricated via this method not only demonstrate high sensitivity but also exhibit exceptional thermal stability, remaining operational at temperatures up to 1200 °C [25]. However, the precise control of the focal point and the resulting photothermal effects remains a significant challenge, impacting the process’s precision.

Capitalizing on recent advancements in the precision of CO2 laser systems, researchers have begun to fabricate more sophisticated SM-LPFGs. For instance, Huang et al. [26] inscribed periodic grooves onto an Anti-Resonant Hollow-Core Fiber (AR-HCF). By leveraging the fiber’s intrinsic low cross-sensitivity and high radiation resistance, they demonstrated robust strain and bending sensing in extreme environments, including those with intense radiation. In another notable work, Liu et al. [27] introduced a point-by-point exposure technique to induce an asymmetric refractive index modulation directly within the fiber core. This selectively excites the LP15 and LP06 higher-order modes, which exhibit distinct responses to bending. By differentially demodulating their resonant peaks, high-sensitivity, low-crosstalk curvature measurements were achieved. Furthermore, the field is beginning to explore synergies with Artificial Intelligence (AI), utilizing AI models to demodulate complex spectral responses [28]. This approach aims to enable the development of low-cost, scalable, multi-parameter sensing networks, thereby paving the way for large-scale industrial applications.

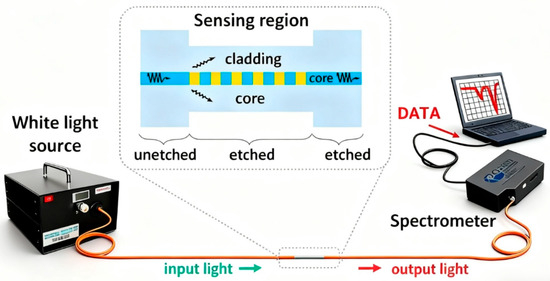

2.2. HF Corrosion Method Fabrication of SM-LPFGs

The chemical etching of the fiber cladding using hydrofluoric acid (HF) is a prominent method (Figure 3). This strategy’s efficacy stems from the high etching selectivity of HF for SiO2. This property allows HF to be used either for direct etching or as a developing agent to reveal patterns pre-inscribed by other techniques, such as femtosecond lasers. In either case, as the cladding is exposed to HF, the resulting fluorosilicic acid product is water-soluble [29], allowing for the creation of precise, periodic groove structures. This process imparts a periodic structural modulation, and the SM-LPFGs fabricated via this method can be broadly classified into two categories.

Figure 3.

HF corrosion method fabrication of SM-LPFGs.

The first category is a hybrid, laser-assisted chemical etching process. This approach begins with a femtosecond laser inscribing a periodic pattern of material modification either within the fiber volume or on its surface. Subsequently, the fiber is immersed in an HF solution. A significant difference in chemical stability exists between the laser-modified and pristine regions, leading to a pronounced differential etch rate [30]. This high etching selectivity effectively transfers the laser-written pattern into a physical structure of deep, well-defined grooves, enabling the efficient fabrication of SM-LPFGs with varying groove depths.

A second category utilizes direct HF etching to either inscribe periodic grooves—inducing geometric asymmetry for enhanced stress sensitivity—or uniformly reduce the cladding diameter, which amplifies the evanescent field’s interaction with the surrounding medium to boost refractive index (RI) sensitivity. This enhanced RI sensitivity is a direct precursor to high-performance, analyte-specific sensing. This technique can also be integrated with the functionalization of a TiO2 nanofilm, which has been shown to achieve an exceptional salinity sensitivity of 163.299 pm/% [31]. Furthermore, when applied to a Polarization-Maintaining Fiber (PMF), HF etching not only enhances sensitivity but also leverages the fiber’s intrinsic birefringence. This endows the SM-LPFG with vectorial sensing capabilities—the ability to discern the direction of physical quantities like bending—while simultaneously reducing polarization-dependent loss [32,33]. This permanent physical deformation, created by direct material removal, has been demonstrated to improve RI sensitivity by more than threefold [34]. However, this significant gain in sensitivity typically comes at the expense of the fiber’s mechanical integrity.

In conclusion, whether employed as a selective etching step following laser modification or for direct periodic thinning, the HF etching method is remarkably effective at enhancing sensor sensitivity. While it holds potential for large-scale production, significant barriers to its wider adoption remain. These include the inherent degradation of the fiber’s mechanical strength, the considerable safety risks associated with the high toxicity of HF, and pressing environmental concerns.

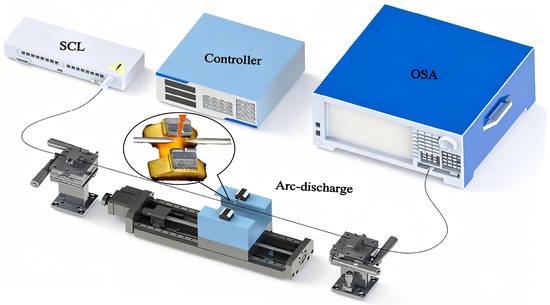

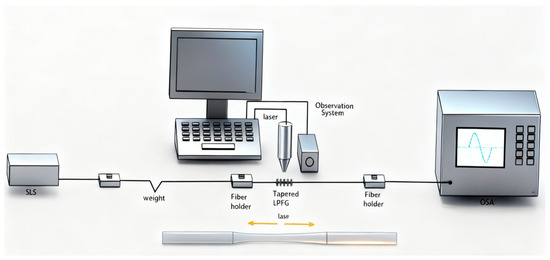

2.3. Arc-Discharge Fabrication of SM-LPFGs

The electric arc discharge technique is a method for fabricating SM-LPFGs through localized, thermally-induced physical deformation, as illustrated in Figure 4. This method utilizes the instantaneous high temperature generated by a high-voltage electric arc to locally fuse the optical fiber. This process is typically accompanied by two key physical phenomena: the formation of a micro-taper when the fiber is under axial tension, and the densification of the core and cladding materials upon rapid cooling. The periodic modulation of the grating arises from the combined effects of this geometric deformation and the induced refractive index change, both of which contribute to enhancing the sensitivity of the resulting LPFGs.

Figure 4.

Fabrication of SM-LPFGs by Tapering.

Based on this principle, the development of the arc-discharge technique has evolved along two primary trajectories. The first is direct periodic geometric modulation, where a sequence of micro-taper structures, formed by periodic arc discharges, constitutes the SM-LPFG. In this case, the grating’s properties stem primarily from the geometric discontinuity along the fiber. Yin et al. [35] demonstrated high-precision control over the micro-taper morphology using the arc discharge unit of a commercial fusion splicer, laying the groundwork for the method’s process stability. The second trajectory utilizes the arc as a tool for post-processing or structural modification. For instance, applying an arc to a pre-side-polished fiber can induce a directional core offset via non-uniform surface tension, thereby creating SM-LPFGs capable of vectorial bend sensing [36]. The arc discharge also serves as a flexible post-processing sensitization technique. For example, localized tapering of a pre-existing LPFG can enhance the evanescent field in a specific region or more efficiently excite higher-order cladding modes, significantly boosting the device’s response sensitivity to RI or bending [37,38]. Furthermore, the fusion capability of the arc has given rise to a unique fabrication modality: a fiber is first periodically etched, then locally heated with an arc. The surface tension reflows and reshapes the grooved sections, restoring a more cylindrical geometry. SM-LPFGs fabricated this way can exhibit induced core deformation, which dramatically enhances their response to external physical parameters, with a particularly pronounced improvement in strain sensitivity.

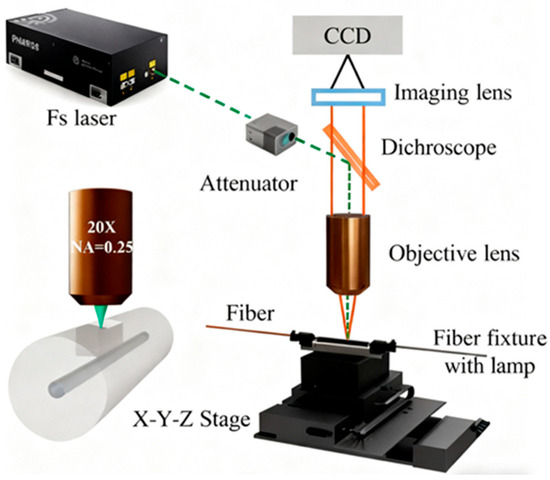

2.4. Fabrication of SM-LPFGs by Femtosecond Laser

Fabrication of SM-LPFGs using femtosecond lasers offers distinct advantages, as illustrated in Figure 5. The process enables highly flexible structural modulation—creating features like grooves or voids on the surface, cladding, or core without requiring hydrogen loading. Unlike thermal methods such as CO2 laser or arc discharge, the femtosecond laser’s ultrashort pulses and nonlinear absorption mechanism minimize.

Figure 5.

Fabrication of SM-LPFGs by femtosecond laser.

The fabrication principles for femtosecond laser inscription can be divided into four main categories:

- (a).

- Refractive Index Modulation: Induces a permanent, localized refractive index change within the fiber via multiphoton absorption at the focal point.

- (b).

- Structural Ablation: Directly ablates material using a “cold ablation” effect to etch periodic structures, such as grooves, onto or within the fiber.

Early work with ultraviolet (UV) femtosecond lasers, while promising [39], often required hydrogen loading and still presented thermal challenges. The field has since shifted to near-infrared (NIR) femtosecond lasers (~800 nm) [40]. These systems deposit energy primarily through nonlinear multiphoton absorption, confining structural modification to the sub-micrometer focal volume. This approach eliminates thermal diffusion and collateral damage, allowing for the direct inscription of highly asymmetric refractive index profiles within the core without photosensitization. Recent applications leverage these capabilities for high-performance sensors. For example, etching micro-cavities enhances evanescent field interaction for high RI sensitivity [41]. The resulting Type II modifications are thermally stable, enabling sensors for extreme environments. Asymmetric inscription creates vector sensors capable of discerning bend direction [42], while point-by-point writing allows for the monolithic integration of multiple devices, such as cascaded LPFGs and Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs), to reduce cross-sensitivity [43].

The phase mask method is distinguished by its superior process stability and reproducibility, establishing it as a cornerstone for the high-fidelity, large-scale manufacturing of gratings [44,45]. However, this technique induces minimal physical disruption to the fiber cladding, its potential for sensitivity enhancement is inherently limited. It is therefore, strictly speaking, a refractive index modulation rather than a structural modulation engineered to compromise cladding integrity.

The femtosecond laser point-by-point direct-write technique represents the apex of bespoke SM-LPFG fabrication, granting researchers unparalleled freedom to meticulously sculpt intricate microstructures within the core with near-arbitrary complexity. Whether inscribing periodic features in specialty fibers to explore mode-coupling physics in the mid-infrared [44] or designing complex architectures to construct functional, temperature-insensitive sensors [46], this technology has demonstrated a formidable capacity for engineering customized spectral responses [47]. This profound flexibility is a potent catalyst, continually driving the development of advanced sensors with novel sensing modalities.

2.5. Others

The aforementioned techniques function by inducing pronounced structural modifications—typically physical disruption or diameter reduction—to directly inscribe the grating [48]. In stark contrast, other approaches either impart a more subtle effect on the cladding or, like uniform fusion tapering (such as Figure 6), are in their elemental form incapable of forming an LPFG independently [49]. They must therefore be synergistically combined with embedded structures or other modulatory forms to realize an SM-LPFG [50].

Figure 6.

Fabrication of SM-LPFGs fusion tapering.

Beyond the canonical approaches to structural modulation, several emergent techniques also construct SM-LPFGs by introducing microscopic structural dissimilarities. For instance, doping with specialized compositions, such as fluorides, circumvents the reliance on intrinsic material photosensitivity, while the phase mask technique offers a mature pathway for high-precision periodization.

The tapering method’s core advantage lies in enhancing the evanescent field’s interaction with the external environment by reducing the fiber diameter, thereby boosting sensitivity to bending and RI by orders of magnitude. This versatility allows for the creation of vector sensors [51] and integrated systems for multi-parameter measurement [52]. However, this technique confronts a fundamental trade-off: despite straightforward fabrication via various means [53,54], the physical diameter reduction that enables high sensitivity inherently causes mechanical fragility, limiting the sensor’s long-term applicability in demanding environments.

Crucially, the principle of thermo-mechanical modulation has been leveraged to pioneer SM-LPFG fabrication in non-silica fibers. This circumvention of material photosensitivity is particularly impactful for substrates like fluoride glass, enabling the creation of purely structural gratings for the first time in such materials and thus opening a new frontier for device engineering [55].

Overcoming this mechanical bottleneck without compromising sensing performance is therefore a key research frontier. Promising approaches include composite fabrication, where a polymer recoating partially restores mechanical integrity after tapering and grating inscription [56], and the heterogeneous integration of tapered structures with functional materials to construct advanced sensors with directly dictates its unique advantages and inherent limitations in the development of specific sensor types.

With performance gains from single fabrication techniques for SM-LPFGs now approaching a plateau, the research focus is shifting toward synergistic, hybrid methodologies. These approaches combine grating inscription with subsequent structural modifications—such as core-reconstruction, side-polishing, or core-offset splicing—to forge devices aimed not merely at enhanced sensitivity or superior overall performance, but at acquiring entirely new functional dimensions, like directional selectivity.

The field of SM-LPFG fabrication is progressively advancing toward the integration of multiple technologies and the adoption of intelligent manufacturing paradigms. To this end, researchers have already begun to integrate these fabrication methods. For instance, combining the precision pre-processing capabilities of femtosecond lasers with subsequent selective HF etching, or applying arc-discharge as a post-processing step to gratings initially inscribed by CO2 lasers, have both been demonstrated to yield substantial enhancements in sensor sensitivity. Dual-parameter SM-LPFGs sensitive to different parameters can be fabricated. The advantages and disadvantages of different preparation methods for SM-LPFGs are summarized, as illustrated in Figure 7, and the types of LPFGs suitable for fabrication by each preparation method are further elaborated on, with comparisons presented in Table 1.

Figure 7.

Comparison of characteristics of SM-LPFGs altered by different fabrication methods: The various fabrication methods are distinguished by their underlying mechanisms, which dictate their respective advantages and limitations regarding precision, cost, and mechanical integrity.

Table 1.

Comparison of different types of sensors based on SM-LPFGs fabricated by different methods.

More critically, the integration of AI models and machine learning [57] for the adaptive optimization of fabrication parameters and the intelligent demodulation of complex spectral responses presents a promising pathway to overcoming the current challenges in the scalable, commercial production of high-sensitivity SM-LPFGs.

3. Characterization of SM-LPFGs

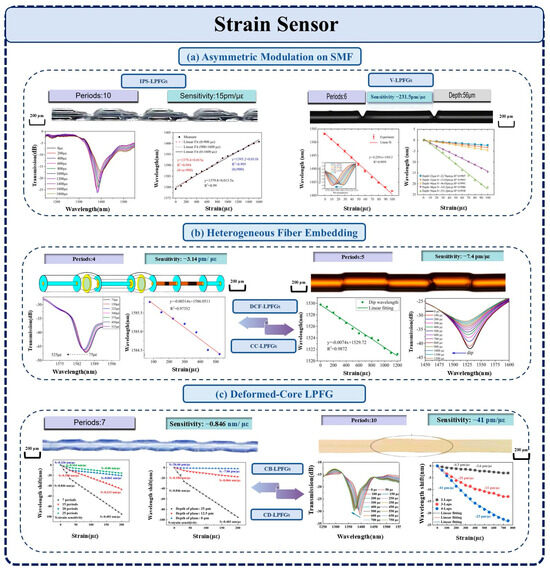

3.1. SM-LPFGs for Strain Sensing

Axial strain represents a critical measurand in structural mechanics and health monitoring. The intrinsic strain sensitivity of LPFGs makes them an excellent platform for developing high-performance strain sensors. Building upon this principle, SM-LPFGs significantly amplify the sensing response by incorporating precisely engineered structural asymmetries. However, the strain sensitivity of such sensors is not a fixed parameter but is instead governed by a combination of factors, including the fabrication method, grating period, and the specific geometry of the induced asymmetry.

From a mechanistic standpoint, the strain-induced shift of the resonant wavelength λ arises primarily from two contributions: (a) the physical alteration of the due to elongation or compression, and (b) the change in the effective refractive indices of the core and cladding via the elasto-optic effect [54]. This relationship can be expressed as:

where is the resonant wavelength, is the applied strain, and is the inscribed grating period.

In the context of stress measurement, applied tensile stress alters the fiber’s refractive index profile, which in turn shifts the resonance peak [55]. This alteration is a composite of multiple physical effects, and their weighted contribution is captured by the change in the effective refractive index, as detailed in Equation (3):

: The change in refractive index due to the residual stress inherent in the fiber from the manufacturing (drawing) process.

: The change caused by the side-polishing process, which creates the D-shaped fiber and alters the stress distribution and waveguide geometry.

: The change induced by the microbending applied to the fiber, which is the mechanism used to form the long-period grating in their setup.

: The change resulting from the elasto-optic effect when the fiber is under axial strain or tension.

For strain sensing applications, the spectral shift of the resonance peak is predominantly driven by the combined effects of axial tension and strain-induced micro-bending. Consequently, enhancing both the sensitivity and the dynamic range of SM-LPFGs remains a key challenge in the field. Current strategies primarily focus on amplifying the sensor’s response to strain by optimizing the grating period and increasing the degree of cladding perturbation.

These fabrication strategies can be broadly classified into three types: (a) creating asymmetric geometries using techniques like laser ablation or mechanical polishing, which not only boosts sensitivity but can also impart vectorial sensing capabilities; (b) periodically incorporating segments of heterogeneous fiber, an approach that benefits from a relatively mature fabrication process while preserving good mechanical robustness; and (c) inducing core deformation through the combined application of multiple modulation techniques, a strategy that can dramatically enhance strain sensitivity. Nevertheless, several challenges hinder the scalable production of certain SM-LPFG designs, including insufficient mechanical integrity, low fabrication throughput, process complexity, and the high cost of specialized equipment. The prepared SM-LPFGs are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Strain sensor: The enhancement of strain sensitivity in SM-LPFGs is principally realized through three structural methods. These include (a) direct, asymmetric geometric modification of the SMF cladding via micro-grooving or side-polishing; (b) fabricating embedded heterogeneous structures where interfaces, created by misaligned splicing or fiber integration, serve as stress concentration points that amplify the strain-optic effect; and (c) implementing fiber core-bending techniques that reshape the light-guiding path to unlock ultra-high sensitivities.

A mainstream strategy for fabricating SM-LPFGs involves the use of a CO2 laser to inscribe structures directly onto a single-mode fiber (SMF). For instance, in 2021, Jin et al. [56] developed D-shaped LPFGs (D-LPFGs) through periodic single-sided fabricating. The grating was composed of repeating units, each containing five D-shaped regions and one unpolished flat region. This configuration achieved a high strain sensitivity of 10.75 pm/με alongside a remarkably low thermal cross-sensitivity of only 0.013 με/°C, thereby mitigating the long-standing issue of temperature cross-talk in LPFGs. In the same year, Sun et al. [58] employed a specialized staggered polishing process to create S-type LPFGs (S-LPFGs), which demonstrated an even higher strain sensitivity of 16.55 pm/με. In both designs, the deliberate disruption of the fiber’s cylindrical symmetry leads to stress concentration at the polished surfaces or groove edges under axial strain, which in turn amplifies the elasto-optic effect. Also in 2021, Ma et al. [59] introduced an innovative approach by fabricating an Incline Plane-Shaped LPFG (IPS-LFG) with a total length of only 5 mm. This compact device exhibited a broader sensing range, higher sensitivity, and excellent linearity across different strain regimes. Although all three of these SM-LPFGs were fabricated using a CO2 laser, their distinct cross-sectional geometries give rise to fundamentally different stress response mechanisms, which explains their varied sensitivities. By converting a uniform external axial strain into a highly non-uniform internal stress field, these structures not only enhance the LPFG’s sensitivity but can also endow it with vectorial discrimination capabilities, thus optimizing its overall sensing performance. This direct-writing approach on SMF is cost-effective and efficient but can be operationally complex.

An alternative fabrication paradigm involves creating periodic structural modulation by embedding segments of other fiber types within an SMF or by using misaligned fusion splicing [60]. For example, Zhang et al. [61] fabricated an ultra-long-period fiber grating (SMS-ULPFG) by alternately splicing sections of SMF and multi-mode fiber (MMF). The strong refractive index modulation and significant core mismatch in the MMF segments enabled the efficient excitation of higher-order cladding modes. To further advance this concept, Zhang et al. [62] in 2020 developed a multimode fiber chirped LPFG (MC-LPG) by non-uniformly embedding eight MMF segments of varying lengths (from 50 μm to 400 μm) into an SMF. Under applied strain, the two resultant resonance peaks exhibited a blue-shift and a red-shift with sensitivities of −10.10 pm/με and 4.22 pm/με, respectively. This feature not only tripled the overall sensitivity but also created the potential for simultaneous dual-parameter demodulation. A drawback of such cascaded structures, however, is their increased overall length, which can limit their application in spatially constrained environments.

More recent advances have focused on increasingly sophisticated geometric heterostructures. In 2022, Chen et al. [63] proposed a device fabricated by embedding short sections of fiber with core diameters of 105 μm and 60 μm into an SMF. This structure demonstrated exceptional strain sensing performance by leveraging core diameter mismatch to excite high-order cladding modes. By carefully designing the grating period to be near the dispersion turning point (DTP), they achieved a strain sensitivity of −15.06 pm/με within a compact length of only 3.6 mm. The high sensitivity is attributed to the fact that the group effective index dispersion changes precipitously near the DTP. In the same year, Fu et al. [64] embedded a dumbbell-shaped dual-core fiber (DCF) into an SMF. Compared to structures incorporating MMF or no-core fiber (NCF), the dumbbell-shaped LPFG alters the modal field distribution within the fiber. Consequently, when subjected to axial strain, this unique structure induces a more pronounced change in mode coupling, resulting in a stronger resonance peak response and greater stability over a wide strain range.

Hybrid fabrication approaches, integrating multiple techniques, have unlocked superior performance in SM-LPFGs. In a pioneering work from 2024, Niu et al. [65] combined mechanical polishing with periodic arc discharge. By carefully controlling the number of discharge events, they engineered a D-shaped LPFG (D-LPFG) with three-tiered, adjustable sensitivity, achieving an impressive 174.55 pm/µε within the micro-strain range of 0–100 µε. The underlying mechanism is that an increased number of discharges intensifies the micro-bending effect in the fiber core, thereby enhancing mode coupling efficiency. The resulting sensor exhibits an array of advantages, including excellent linearity, minimal thermal cross-talk, low hysteresis, and a flexible dynamic range. Furthermore, the asymmetric D-shaped structure imparts a pronounced selectivity to the direction of axial strain. In 2025, Yin et al. [66] fabricated a V-groove LPFG (V-LPFG) by periodically inscribing grooves (angle α = 60°, depth h = 56 μm, period Λ = 590 μm) on one side of an SMF using a CO2 laser. This sensor demonstrated a remarkable average sensitivity of −229.1 pm/με in the 0–100 με strain range. The V-groove structure introduces significant, periodic stress concentration points, which amplify both the photoelastic effect and the impact of structural deformation on mode coupling. As the groove depth increases, the stress concentration becomes more pronounced, leading to enhanced sensitivity. This exceptionally high response is a direct consequence of the stress amplification at the sharp tip of the V-groove, which magnifies the local strain effect.

Another frontier in SM-LPFG design involves the direct modulation of the fiber core’s geometry—a strategy that unlocks even greater sensitivities compared to cladding-based modifications. Li et al. developed Helical LPFGs [67] (H-LPFGs) and Core-Distortion LPFGs [68] (CD-LPFGs) through processes combining pre-twisting with side-etching, with the latter demonstrating a significantly improved sensitivity of −41 pm/µε within a 350 µε range and low cross-sensitivity. In 2025, Liang [69] fabricated a Hook-Shaped Core LPFG (HSC-LPFG) using a misaligned fusion splicing technique. Its core principle hinges on the straightening of the “hook-shaped” core region under axial strain, which induces a drastic change in the effective optical path and refractive index modulation. This compact structure achieved a sensitivity as high as −135 pm/με within a mere 3 mm sensing region. Critically, the work also introduced a second-order measurement matrix to decouple the spectral shifts caused by temperature and strain. In a recent breakthrough, Ma et al. [70] proposed a novel Core-Bending LPFG (CB-LPFG). The intricate fabrication involved symmetric 25 μm side-polishing of an SMF, followed by the etching of periodic V-grooves, and a final step of localized heating and tapering with an oxyhydrogen flame to reshape the non-circular structure back to a circular cross-section. The CB-LPFG exhibited unprecedented strain sensitivity, reaching −0.846 nm/με and −0.403 nm/με in the 0–30 µε and 30–200 µε ranges, respectively. This work represents a landmark achievement, pushing the strain sensitivity of a fiber optic sensor based on single-wavelength demodulation into the nm/με regime for the first time. Its extreme sensitivity enables the detection of faint physiological signals, such as muscle tremors or pulses, foreshadowing its vast potential in biomedical applications. In essence, these core-distortion architectures modulate the light’s propagation path far more effectively, making the entire core-cladding system acutely responsive to external stress and thus dramatically enhancing sensitivity to minute strains.

The fundamental design philosophy of SM-LPFGs is to replace or augment traditional photo-induced refractive index modulation with engineered physical modifications to the fiber structure, thereby enhancing strain sensitivity. However, these different technological pathways exhibit significant disparities across the three critical dimensions of sensing performance, fabrication controllability, and mechanical reliability. As an important sensing technology, SM-LPFGs offer considerable advantages due to their low fabrication costs and operational simplicity, with demonstrated strain sensitivities now reaching the nanometer-per-microstrain level. Table 2 compares the performance of SM-LPFGs fabricated using these various methods. Nevertheless, the bulk of existing research has concentrated on standard SMF platforms. A comparatively nascent research base exists for structures that embed non-traditional fibers—such as offset-core, dual-core, or multi-core fibers within an SMF host. Given the recent proliferation of research into modified core structures, we contend that offset-core fibers, owing to their unique geometry, offer a particularly promising avenue for the fabrication of next-generation, high-sensitivity core-distorted SM-LPFGs.

Table 2.

Strain range and corresponding strain sensitivity of SM-LPFGs.

3.2. SM-LPFGs for Torsion Sensing

The structural health monitoring (SHM) of mechanical systems imposes stringent demands on torsion measurement. Conventional electrical sensors, however, face significant limitations in complex environments due to their bulk and susceptibility to electromagnetic interference (EMI). Standard, uniform LPFGs, characterized by their intrinsic cylindrical symmetry, are inherently insensitive to torsional stress and thus cannot be directly employed for such applications. To address this challenge, research has focused on introducing periodic structural asymmetry, leading to the development of SM-LPFGs for torsion sensing.

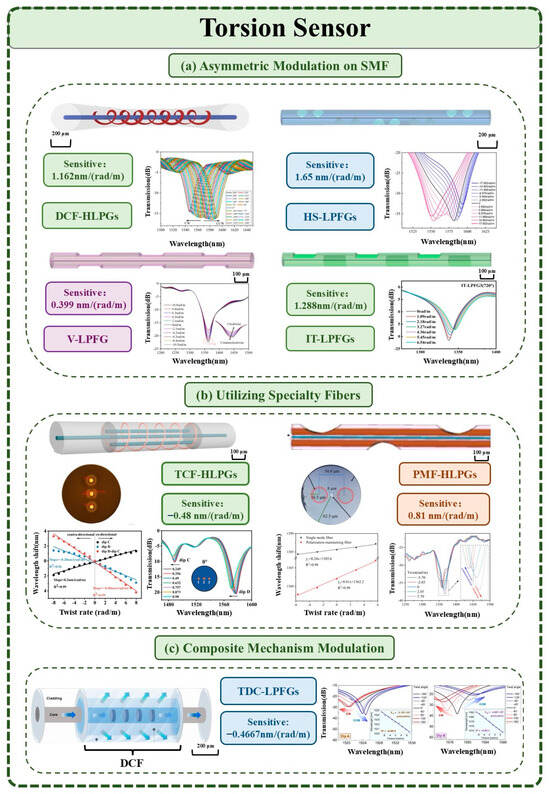

Pioneering work by Lin et al. first demonstrated the viability of this approach by fabricating a periodically corrugated SM-LPFG via chemical etching, confirming that the induced asymmetry enables a resonant wavelength shift in response to torsion [71]. Building on this, the same group later utilized this structure to achieve significantly enhanced torsion sensitivity [72]. The underlying physical principle is that an applied twist causes shear stress to concentrate and redistribute across the regions of varying diameter in the corrugated grating. This redistribution alters the phase-matching condition for mode coupling, resulting in a measurable shift of the resonant wavelength that corresponds to the magnitude and direction of the applied torsion. Some of the SM-LPFGs used for the correction are shown in Figure 8.

A key strategy for enhancing torsion sensitivity involves the introduction of complex geometric configurations onto standard single-mode fibers (SMFs) through precision micromachining. Deng et al. [12] pioneered a direct structural modulation approach to create a chiral, non-helical pre-twisted LPFG (PT-LPFG). This design achieved an impressively broad torsion measurement range of ±57.1 rad/m with only minimal modification to the SMF. An alternative pathway involves the direct inscription of geometric features. In 2021, Lu et al. [73] demonstrated a V-groove LPFG (V-LPFG) fabricated by polishing both sides of the fiber, a relatively simple method that yielded a torsion sensitivity of 0.399 nm/(rad/m). The underlying mechanism is that torsional shear stress, which is zero at the fiber’s core and increases linearly to a maximum at its periphery, becomes highly concentrated within these V-grooves. This stress concentration results in a sensitivity enhancement of an order of magnitude compared to ungrooved structures. Similarly, Saputro et al. [74] employed a pre-twisting fabrication process for double-clad LPFGs (TDC-LPFGs), attaining a high sensitivity of −0.4667 nm/(rad/m) over a range of ±9.69 rad/m.

Building on these direct-writing techniques, more sophisticated fabrication processes have further advanced the sensitivity of SM-LPFGs by integrating multiple methodologies. In 2022, Jin et al. [75] developed a novel method combining rotational V-groove inscription with oxyhydrogen flame drawing. This process induced and permanently “froze” a periodic helical core structure within the SMF, creating a helix-style LPFG (HS-LPFG). The technique not only significantly enhanced the linear birefringence but also effectively introduced circular birefringence via residual torsional stress. The synergistic interplay between these two effects dramatically amplified the overall elliptical birefringence, leading to an exceptional torsion sensitivity of 1.65 nm/(rad/m). More recently, in 2025, Kang et al. [76,77] proposed two distinct SM-LPFG designs: a rotating distributed slot type (RD-LPFG) and an indirect torsion slot type (IT-LPFG). The RD-LPFG was fabricated through a multi-step process involving helical slot inscription with a high-frequency CO2 laser followed by a twist-and-release procedure. This locked in residual stress, breaking the fiber’s circular symmetry and synergistically enhancing both linear and circular birefringence to achieve a sensitivity of 0.42 nm/(rad/m). Their IT-LPFG, created using an alternating twist–inscription process, induced differential refractive index modulation in adjacent grooved regions. This accelerated the rotation of the principal polarization axis, boosting sensitivity to 1.288 nm/(rad/m). Both designs leverage residual stress to engineer the fiber’s birefringence. The specific geometry of the inscribed slots serves to redistribute torsional stress over a wider area, reducing local stress peaks and thus mitigating the risk of fracture. Furthermore, these helical groove structures provide a continuous path for torque transfer, enabling more uniform stress propagation along the fiber.

As research progressed, leveraging the unique structural advantages of specialty optical fibers emerged as a key strategy for advancing torsion sensor performance. Fibers such as dual-core fiber (DCF), polarization-maintaining fiber (PMF), and multi-core fiber (MCF) provide ideal platforms for torsion sensing due to their inherent structural asymmetry. For instance, Zhang et al. [78] inscribed a helical LPFG in a two-mode fiber (TMF-HLPG), achieving a sensitivity of 0.47 nm/(rad/m)—an order of magnitude greater than conventional LPFGs—and enabling bidirectional torsion measurement. In 2023, Dai et al. [79] utilized a CO2 laser to ablate periodic, 500 μm complementary grooves along the principal stress axes of a PMF, creating an LPFG with tunable sensitivity (TS-LPFG). In 2024, Zhang et al. [80] further amplified sensitivity by embedding a PMF-LPFG within a Sagnac interferometer. This configuration allowed the light to interact with the grating multiple times, boosting the sensitivity by a factor of 22 compared to standard LPFGs. Similarly, Zhao et al. [81] leveraged the asymmetric core arrangement of a three-core fiber (TCF) to fabricate a TCF-LPFG capable of high-sensitivity torsion detection with direction discrimination. MCFs are particularly advantageous; their non-centrosymmetric core layout leads to differential strain and refractive index changes among the cores under torsion, enhancing sensitivity and enabling direction determination. However, despite the performance gains offered by specialty fibers like MCFs and PMFs, their complex structures often lead to higher manufacturing costs and reduced mechanical robustness when fabricating SM-LPFGs.

To push the performance boundaries further, cutting-edge research focuses on hybrid modulation strategies that combine helical geometries with other physical phenomena. These approaches often incorporate principles of topological optimization from mechanical engineering to create structures better suited for torque propagation. For example, Zhu et al. [82] ingeniously combined a helical structure with the dispersion DTP of an LPFG. Capitalizing on the extreme sensitivity of the DTP to external perturbations, they designed a customizable helical LPFG (DTP-C-HLPG) using two cascaded DTPs, achieving an ultra-high torsion sensitivity of 2.731 nm/(rad/m). This remarkable performance is attributed to the inherent high sensitivity at the DTP, further amplified by the reduced fiber diameter. More recently, in 2024, He et al. [83] inscribed a helical LPFG in an etched double-cladding fiber (DCF-HLPG). This design introduces an evanescent field enhancement mechanism. By chemically etching the DCF to reduce its diameter before grating inscription, they not only boosted the torsion sensitivity from 0.342 nm/(rad/m) to 1.162 nm/(rad/m) but also maintained low cross-sensitivity to strain over a wide measurement range. This dual benefit ensures that the sensor can accurately measure torsion while effectively rejecting interference from non-target measurands, thereby significantly enhancing its reliability.

In essence, conventional LPFGs are inherently insensitive to torsion due to their symmetry. SM-LPFGs significantly improves the performance of the sensor through structural modulation, as shown in Figure 9. The development of SM-LPFGs, which introduce engineered asymmetries like helical grooves, provides an effective strategy to overcome this limitation by dramatically enhancing sensitivity and strategically managing stress. Specific examples are shown in Table 3. Despite their performance advantages, the cost and fabrication complexity of specialty fibers favor SMF-based platforms for scalable applications. Future research directions include optimizing structural designs for greater coupling efficiency and reproducibility, alongside exploring material enhancements, such as doping, to improve mechanical robustness. Progress in these areas is crucial for unlocking the full potential of SM-LPFGs in demanding fields like structural health monitoring [84], intelligent robotics, and renewable energy systems.

Figure 9.

Torsion sensor: Torsion-sensitive SM-LPFGs rely on introducing structural anisotropy through three primary strategies: (a) the direct inscription of chiral structures and helical gratings, onto an SMF to translate torsional strain into a spectral shift; (b) leveraging specialty fibers such as multi-core fibers that possess inherent non-centrosymmetric core arrangements; and (c) exploiting unique physical mechanisms, such as modulating evanescent field interactions in double-clad fibers, to achieve highly sensitive responses.

Table 3.

Torsion range, sensitivity and the methods for achieving bidirectional torsion measurement of SM-LPFGs.

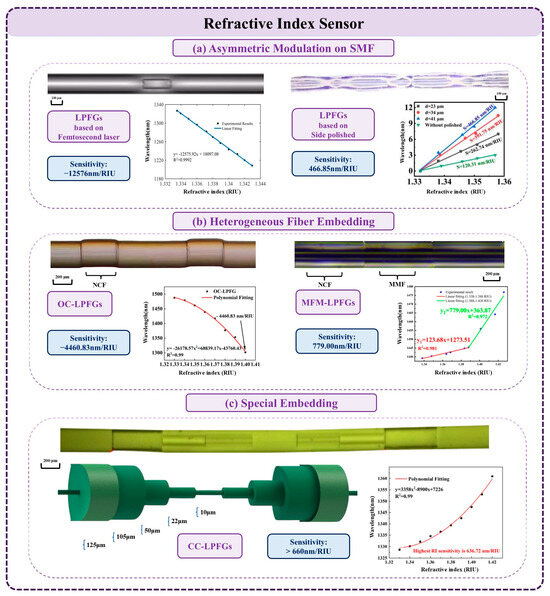

3.3. SM-LPFGs for Refractive Index Sensing

RI sensing operates on the principle that changes in the surrounding RI modulate the effective index of cladding modes, inducing a spectral shift. However, conventional LPFGs are fundamentally limited by low sensitivity, stemming from weak evanescent field interaction, and are often hampered by temperature cross-sensitivity. To overcome these constraints, SM-LPFGs employ precision engineering of the fiber’s physical geometry, with typical examples illustrated in Figure 10. This structural modification approach, distinct from reliance on material photosensitivity, dramatically enhances the light–matter interaction, thereby enabling the development of RI sensors with substantially improved sensitivity and stability.

Figure 10.

RI sensor: The enhancement of RI sensitivity is primarily achieved by strengthening the interaction between the evanescent field and the surrounding medium. This is realized via three main routes: (a) geometric reshaping of a standard SMF through tapering or micro-inscription; (b) employing specialty fiber) that inherently facilitate field exposure; and (c) fabricating heterogeneous structures by embedding multiple fiber types.

Direct periodic inscription on SMFs represents a primary method for fabricating RI sensors. In 2022, Ma et al. [85] introduced sinusoidal-core LPFGs (SC-LPFGs), created by laser-inscribing offset V-grooves followed by a fusion-tapering process. This technique induces a sinusoidal bend in the fiber core, bringing portions of it closer to the fiber’s surface. The resulting structure achieved a high sensitivity of 620 nm/RIU around an RI of 1.42 and demonstrated temperature self-compensation by leveraging a dual-resonant peak. In a quest for even greater sensitivity, Gao et al. [41] employed a femtosecond laser to inscribe cubic microcavities that penetrate the SMF core. This design allows the analyte to directly fill the cavity, enabling strong interaction with the core’s optical field and yielding an ultra-high sensitivity of −12,576 nm/RIU within the narrow 1.3335–1.3430 RIU range. These approaches, based on direct structural modulation of SMFs, demonstrate the viability of creating high-performance RI sensors. While techniques like side-polishing can also significantly boost sensitivity, they often require the application of overlays [86]. Although SMFs offer a cost-effective platform, the successful implementation of these advanced fabrication methods is highly dependent on precision instrumentation and expert operation.

An alternative and powerful approach involves the use of embedded SM-LPFGs, which can yield substantial improvements in RI sensitivity. This technique involves periodically splicing and embedding segments of different fiber types into an SMF. The engineered mode–field mismatch between the dissimilar fibers efficiently excites higher-order cladding modes that are highly sensitive to the surrounding RI. This design strategy not only allows for flexible control over mode-coupling characteristics to enhance RI sensitivity but also enables intrinsic temperature stability through careful material and structural optimization. No-core fiber (NCF) is a frequently used component in this context, as it allows the guided mode to expand fully into the external environment. For instance, by periodically embedding NCF segments within an SMF, Geng et al. [87] constructed a sensor with an RI sensitivity of 141.837 nm/RIU and negligible temperature cross-sensitivity. More recently, in 2024, Yin et al. [88] designed a novel LPFG by embedding a coaxial dual-waveguide fiber structure within an NCF segment, which was then spliced into an SMF (CEN-LPFGs). This device exhibited two distinct resonant peaks with RI sensitivities of 183.62 nm/RIU and 278.44 nm/RIU, and corresponding temperature sensitivities of −27.67 pm/°C and 37.5 pm/°C.

To push the sensitivity limits even further, researchers are combining embedded designs with other structural enhancement techniques. In 2023, Liu et al. [32] proposed a tapered two-mode fiber embedded LPFGs (TTMF-LPFGs). The device was fabricated by alternately splicing 50 µm segments of TMF and SMF to form a four-period structure, which was then tapered to a waist diameter of 36 µm. This configuration leverages a three-fold synergistic effect: the tapered region enhances evanescent field penetration, tapering-induced redistribution excites higher-order cladding modes, and periodic diameter modulation arises from differential thermal expansion during the process. This combination boosted the RI sensitivity to 1360.43 nm/RIU while maintaining low temperature crosstalk. Also in 2023, Tian et al. [89] innovatively applied an offset splicing technique when embedding a hollow-core fiber into an SMF. The resulting structural asymmetry dramatically increased the coupling efficiency between core and cladding modes, catapulting the sensitivity to an impressive −4460.83 nm/RIU. Furthermore, capitalizing on the unique modal properties of few-mode fiber (FMF) has proven effective. Zhang et al. [90] developed an MMF-embedded structure LPFGs (MFM-LPFGs) where the core mismatch between a multimode fiber and the FMF induces strong RI modulation. This sensor achieved a high RI sensitivity of 779.00 nm/RIU alongside exceptionally low cross-sensitivities to temperature and strain, highlighting its potential for use in complex environments. In summary, embedded SM-LPFGs, particularly those incorporating NCF or tapered sections, achieve sensitivities far exceeding conventional LPFGs by either expanding the optical field for greater external interaction or by efficiently exciting higher-order cladding modes, providing a versatile platform for developing customized RI sensors that combine high sensitivity with excellent stability.

Beyond these two mainstream approaches, RI sensitivity in SM-LPFGs can also be enhanced by leveraging unique optical effects or innovative composite structures. For instance, by fabricating an SM-LPFGs in a small-core SMF and operating it near the DTP, one can capitalize on the inherent and extreme sensitivity of the DTP to external RI changes. Du et al. [91] demonstrated the efficacy of this principle, designing an LPFG with a sensitivity as high as 1304 nm/RIU. Another innovative design was reported in 2024 by Chen et al. [92], who created chirped-core LPFGs (CC-LPFGs) by periodically splicing fibers with different core diameters. The mode–field mismatch at the splice joints efficiently excites higher-order cladding modes. This approach achieved a sensitivity of 636.72 nm/RIU while offering significant practical advantages: by avoiding fine etching, it maintains excellent mechanical integrity, simplifies fabrication, and ensures cost-effectiveness.

Innovations in the physical geometry of SM-LPFGs have substantially advanced the performance of LPFG-based refractive index (RI) sensors. The central strategy underpinning these advancements is the enhancement of light–matter interaction, achieved either by strengthening the evanescent field or by efficiently exciting higher-order modes. These approaches can be broadly categorized. The first involves embedded structures, where elements like no-core fibers, few-mode fibers, or tapered sections are spliced into the SMF. This method offers considerable design flexibility, enabling functionalities from high sensitivity to temperature self-compensation, though often at the expense of mechanical robustness. The second category is the direct structural modulation of the SMF itself. By optimizing the geometry of the fiber’s core and cladding, light is more efficiently coupled to higher-order cladding modes, which are highly sensitive to the external RI. These modifications simultaneously enhance the interaction between the evanescent field of these modes and the surrounding analyte. Consequently, even minute changes in the external RI induce a measurable shift in the resonant wavelength. These physical modulations constitute the periodic perturbation that forms the grating itself, with the specific geometry of the modulation dictating the sensor’s unique response to RI. Furthermore, advanced techniques such as operating the device near its dispersion turning point (DTP) or introducing a chirped core structure represent other effective methods of structural modulation. A performance comparison of representative SM-LPFGs for RI sensing is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Measurement range, sensitivity and the structural modulation methods for sensitivity enhancement of SM-LPFG RI sensors.

The research focus for SM-LPFG-based RI sensors is now transitioning from solely pursuing record-breaking sensitivities to developing practical devices that are compact, reproducible, and mechanically robust. Future efforts will likely concentrate on hybrid modulation strategies that merge the benefits of different fabrication techniques and the deeper integration of intelligent algorithms, such as machine learning, to deconvolve complex spectra for multi-parameter sensing. While other configurations like Mach–Zehnder interferometers may offer higher RI sensitivity in specific scenarios, the compelling advantages of SM-LPFGs namely their compact footprint and superior mechanical integrity ensure they remain a highly promising platform for future sensor development.

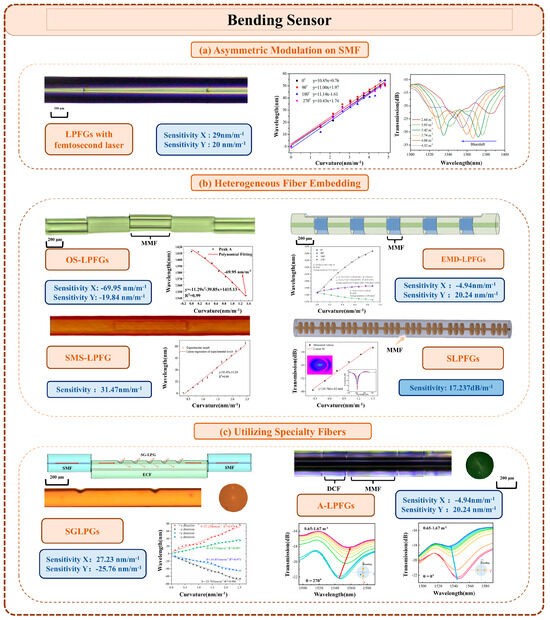

3.4. SM-LPFGs for Bending Sensing

Real-time curvature monitoring is indispensable for ensuring the structural integrity of large-scale systems, from heavy machinery to civil infrastructure like bridges. The failure to adequately monitor bending can lead to catastrophic damage and incalculable losses, making precise curvature sensing essential. LPFGs provide an ideal technological platform to meet the demanding requirements of these applications, offering advantages such as a compact footprint, high sensitivity, immunity to electromagnetic interference, and minimal impact on the host structure. Consequently, they have become a vital technology in fields as diverse as civil engineering, aerospace for monitoring large wind turbine blades, flexible robotics [2], oil and gas exploration for drill string analysis, and minimally invasive medical catheters. A schematic of a typical SM-LPFGs-based bending sensor and its operational principle is illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Bending sensor: There are three primary routes to realize high-performance SM-LPFG bending sensors: (a) direct, in-situ geometric modification of a standard SMF; (b) periodic splicing of heterogeneous fibers to form embedded structures; and (c) employing specialty fibers with intrinsic structural asymmetry.

The effective refractive index profile of the core under periodic modulation can be expressed as:

When LPFGs are subjected to bending, their physical structure can be modeled as a tilted grating. Bending with a radius R induces a minute tilt angle between successive grating periods. This effectively transforms the uniform grating into a structure with a continuously varying tilt and period along its length, analogous to a tilted and chirped fiber grating. As the effective period is shorter than the physical period , the geometric effect combines with the dominant stress-optic effect, causing a shift in the resonant wavelength. Furthermore, the refractive index modulation contrast, represented by , is diminished by bending. This reduction in contrast lowers the grating’s coupling efficiency and weakens the overall strength of the index modulation. The phase offset term, , is related to the grating’s chirp and typically has a negligible influence on the refractive index in a uniform SM-LPFGs.

However, the inherent cylindrical symmetry of conventional LPFGs renders them insensitive to the bending direction and susceptible to cross-sensitivity with other parameters such as strain. Pioneering work by Wang et al. [93] first demonstrated that LPFGs fabricated with a CO2 laser exhibited a distinct response to curvature. Building upon the understanding of this anisotropic response, Wang and Rao [94] deliberately engineered structural asymmetry into the gratings. This innovation enabled, for the first time, the simultaneous measurement of both curvature magnitude and its full 360° orientation. These foundational studies established that structural modulation is the quintessential strategy for developing high-sensitivity, decoupled vector curvature sensors.

Directly introducing asymmetric structures onto an SMF using techniques such as laser inscription or electric arc discharge is a highly effective route to enhance curvature sensitivity. For instance, LPFGs comprising a concave-lens-like array (CCL-LPFGs) [95], inscribed by a CO2 laser, achieved a sensitivity of −32.782 nm/m−1, though they lacked directional discrimination and exhibited blind spots. In 2022, Lai et al. [96] fabricated a V-shaped LPFGs by inscribing an asymmetric V-shaped grating. Compared to conventional planar gratings, this three-dimensional asymmetric structure perturbs the cladding modes more effectively, strengthening the curvature response of the core-to-cladding mode coupling. This design yielded distinct sensitivities of −24.08 nm/m−1 and 21.46 nm/m−1 in the −Y and +Y directions, respectively, and notably improved the sensor’s responsiveness in the micro-curvature regime. Similarly, arc discharge can be used to break the fiber’s symmetry. Zhao et al. [97] developed dual-dip LPFGs (DD-LPFGs) that exhibited different sensing mechanisms in opposite directions—a wavelength-dominant response −35.91 nm/m−1 in one and an intensity-dominant response −20.74 dB/m−1 in the other—thereby achieving unambiguous directional sensing. More recently in 2024, Su et al. [42] fabricated an asymmetric, off-axis SM-LPFGs using a femtosecond laser. By precisely controlling the grating’s offset from the core axis and the number of inscribed periods, they achieved two-dimensional vector sensing over a broad range of 0–4.59 m−1 with a high sensitivity of 29 nm/m−1. Some SMF-based designs have even achieved four-quadrant vector sensing. Xu et al. [36] combined arc discharge and CO2 laser processing to create core-offset LPFGs (CO-LPFGs). The release of residual stress and the effect of surface tension induced a core offset toward the more deeply polished side, resulting in a structure with distinct curvature sensitivities in four orthogonal directions.

Periodically embedding segments of dissimilar fibers, such as multimode fiber (MMF), into an SMF to enhance mode coupling via mode-field mismatch represents another mainstream technical route. Hu et al. [98] and Zhang et al. [99] demonstrated this by embedding MMF segments of 200 μm and 400 μm, respectively, achieving curvature sensitivities as high as 31.47 nm/m−1 with negligible temperature crosstalk. In 2022, Zhang et al. [100] proposed a super-structured LPFGs (SLPFGs) composed of a 600 μm period containing three 50 μm-wide MMF segments. This device operated via amplitude demodulation, achieving a high sensitivity of 17.237 dB/m−1, a scheme that inherently mitigates temperature-induced crosstalk. Jin et al. [101] advanced the embedded MMF design by side-polishing it to form a D-shaped cross-section (EMD-LPFG). This produced a highly compact device (2.5 mm length) with an exceptional sensitivity of 70.21 nm/m−1 in the direction opposite the polished surface, sensitivities of 9.72–9.98 nm/m−1 in the orthogonal directions, and extremely low temperature crosstalk. In 2023, Li et al. [102] reported an ultra-compact (1.5 mm), Omega-shaped LPFGs (OS-LPFGs) capable of multi-directional sensing. It exhibited different sensitivities in the ±X directions, with a peak value of −69.95 nm/m−1 in the −X direction over a 0–1.5 m−1 range. The high performance of such SM-LPFGs is attributed to the strong refractive index modulation from the core mismatch, which is further enhanced by the asymmetry of the Omega shape; this not only boosts curvature sensitivity but is also key to achieving directional sensing.

Beyond structures fabricated in conventional or embedded fibers, specialty fibers are increasingly being employed to create advanced SM-LPFGs, as illustrated in Table 5. This new class of sensors often merges the advantages of embedded structures with advanced inscription techniques, leveraging both material properties and fabrication processes to expand the capabilities of SM-LPFGs. The inherent asymmetry of specialty fibers provides a new design dimension for curvature sensing. Jiang et al. [50] demonstrated that LPFGs inscribed in polarization-maintaining fiber (PMF) could achieve distinct vector responses. In 2022, Xu et al. [103] developed a side-grooved LPFG (SG-LPFG) in an eccentric-core fiber (ECF). This design synergistically combined the intrinsic core eccentricity with the externally induced asymmetry of the groove, resulting in different sensitivities in four orthogonal directions with no significant blind spots. The grooves enhance mode coupling while working in concert with the eccentric core to markedly increase the anisotropy of the curvature response. In 2025, Zhu et al. [104] proposed assembled LPFGs (A-LPFGs) by periodically splicing DCF and MMF, achieving highly effective directional recognition within a 4.35 mm length. In the same year, Su et al. [38] designed a unique SM-LPFG by periodically embedding three staggered NCF and MMF segments into an SMF, followed by tapering the MMF sections. This composite grating structure, with a total length of only 3.22 mm, exhibited a high curvature sensitivity of −42.31 nm/m−1, a low response threshold, and minimal temperature crosstalk. Its enhanced sensitivity is primarily due to the tapered regions, which cause the core field to expand into the cladding, thereby increasing the core-cladding coupling efficiency.

Table 5.

Curvature range and the methods for directional measurement of SM-LPFGs.

In summary, structural modulation has proven pivotal for enhancing the performance of LPFGs curvature sensors. Direct modulation methods offer relative fabrication simplicity but often demand high precision and can introduce stress points that compromise mechanical reliability. The embedded structure approach provides design flexibility and facilitates high sensitivity, though it faces challenges with splicing loss and process complexity. The use of specialty fibers cleverly leverages their intrinsic properties but is often constrained by cost and availability. Despite significant progress, most current sensors are limited to one- or two-dimensional vector sensing and still face challenges in precisely decoupling curvature from axial strain. A primary focus for future research will be the development of more sophisticated structural designs to achieve true three-dimensional vector curvature sensing, paving the way for more reliable applications in complex engineering environments.

3.5. Other Sensing

Beyond the LPFGs categorized by their primary fabrication method, a vast body of work focuses on sensing physical parameters such as temperature, vibration, and magnetic fields. These applications often rely on a synergy between structural modulation and functional materials, rather than on purely structural effects, which is why they are discussed separately here.

To overcome the low intrinsic thermal sensitivity of standard LPFGs, a prevailing strategy is to synergize structural modulation with materials possessing high thermo-optic coefficients. For instance, by using a femtosecond laser to drill micro-channels within the fiber and subsequently filling them with a thermosensitive polymer, a highly efficient interaction volume is created. This approach transforms the LPFG into an ultra-sensitive device, amplifying its thermal response by orders of magnitude [105].

For low-frequency vibration monitoring high-speed intensity demodulation, the core principle involves translating mechanical vibration into dynamic bending of the LPFG, which directly modulates its transmission intensity. LPFG inscribed on a cantilever beam has demonstrated this, enabling high-sensitivity acceleration sensing by simply monitoring optical power fluctuation reliable vibration sensors [106].

Sensing non-mechanical measurands like magnetic fields necessitates integrating LPFGs with transducer materials, such as ferrofluids. Achieving vector sensing, however, fundamentally requires breaking the sensor’s cylindrical symmetry. This has been elegantly achieved by inscribing an LPFG in a polarization-maintaining fiber, where the synergy between the fiber’s intrinsic asymmetry and the field-induced anisotropic distribution of the ferrofluid enables the demodulation of both field strength and direction, unlocking multi-dimensional sensing capabilities [33].

3.6. Dual-Parameter Sensing and Decoupling Strategies

To surmount the cross-sensitivity challenge inherent to LPFGs, two principal approaches have emerged.

The first approach centers on the sophisticated engineering of a single LPFG structure to generate two distinct resonant peaks, each with a differential response to external perturbations. The works previously discussed are archetypal of this strategy: whether leveraging physical asymmetry [107], employing spectral engineering [108], or inducing a helical structure on a specialty fiber [74], the unifying goal is to create the requisite multi-channel sensing capability within a single, compact device.

The second approach, in contrast, achieves decoupling by cascading disparate sensing elements, leveraging the innate differential response of each component. The work by Wang et al. is an exemplary case. By integrating an LPFG, an FBG, a PMF–Sagnac loop, and an SMS structure, they constructed a four-parameter sensing system where each component has a distinct role for instance, the FBG is sensitive to temperature but not to external refractive index, while the LPFG responds to both. While architecturally more complex, this method offers a clear, modular path to higher-dimensional sensing.

Consider the canonical example of simultaneous strain and temperature sensing. The various attenuation dips in the LPFG’s transmission spectrum arise from the coupling of the fundamental core mode to cladding modes of different orders. These distinct mode-coupling pathways inherently exhibit markedly different responses to strain and temperature. This disparity manifests not only as a difference in the magnitude of their respective strain and temperature sensitivities but, in some cases, as a completely antipodal direction of wavelength shift.

When the LPFG is subjected to simultaneous changes in strain and temperature, the resultant resonant wavelength shifts ( and ) for two distinct attenuation dips, m and n can be described by the well-established matrix relationship:

where and represent the sensitivity coefficients for strain and temperature, respectively. From the principles of linear algebra, a unique solution for and exists if and only if the determinant of the sensitivity matrix is non-zero, i.e., . Crucially, for any two distinct cladding modes in an LPFG, this condition is invariably met due to their disparate modal properties. Consequently, by experimentally measuring the wavelength shifts and , the changes in strain and temperature can be unambiguously resolved by inverting the matrix, thereby enabling simultaneous measurement with a single LPFG.

For optimal measurement precision, the operational strategy involves selecting a pair of attenuation dips that maximize the determinant of the sensitivity matrix. This is typically achieved by choosing modes with widely divergent sensitivities. The selection of a mode pair exhibiting antagonistic wavelength shifts is particularly advantageous, as it greatly enhances the numerical stability of the matrix inversion, leading to more robust and accurate decoupling. This kind of decoupling is also applicable to the cascading of FBG and LPFGs [109].

Despite their distinct physical implementations, both approaches ultimately rely on the well-established Sensitivity Matrix Method for mathematical decoupling. By inverting this matrix, the measured spectral shifts can be resolved into precise changes in each measurand, enabling crosstalk-free, multi-parameter sensing.

3.7. Chapter Summary

In essence, the performance of SM-LPFGs is dictated by tailoring the physical geometry to a specific measurand, with representative configurations illustrated in Figure 12. For mechanical sensing, strain sensors achieve ultra-high sensitivity by employing structures that concentrate stress or directly modulate the core’s light path, while torsion sensors depend on introducing structural chirality—typically via helical gratings—to break the fiber’s intrinsic symmetry and respond to twist. In contrast, refractive index sensors maximize performance by enhancing the evanescent field’s interaction with the surrounding medium through techniques like tapering, embedding no-core fibers, or direct core-level micro-structuring. Finally, vectorial curvature sensors also rely on engineered asymmetry, created by methods such as side-polishing or embedding dissimilar fibers, to enable the discrimination of both the magnitude and direction of a bend.

Figure 12.

The sensing modality of an SM-LPFGs is dictated by its structural modulation: asymmetric geometries and core distortions amplify internal stress for ultra-sensitive strain sensing; chiral structures control birefringence for vector torsion measurement; cladding reduction enhances evanescent field interaction for RI sensitivity; and asymmetric embedded structures enable precision vector bending sensing.

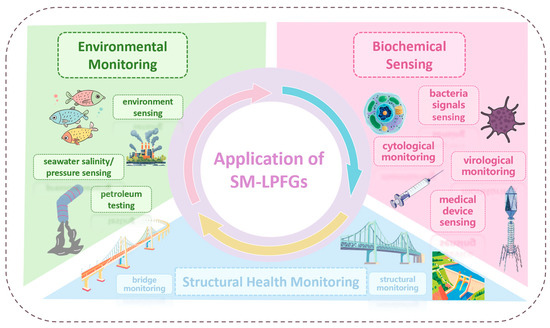

4. Application of SM-LPFGs

The core principle of SM-LPFGs involves optimizing sensing performance through the precise engineering of the fiber structure, a concept illustrated in Figure 13. Two primary technical routes are employed depending on the application. For physical sensing, such as structural health monitoring, periodic geometric modifications like helical profiles amplify the sensor’s response to mechanical parameters like micro strain and torsion. In contrast, biochemical sensing [110] focuses on reducing the cladding diameter via chemical etching or tapering to enhance the evanescent field’s interaction with the external medium. This approach, when combined with surface functionalization, enables the specific recognition of target molecules. This strategic engineering establishes SM-LPFGs as a foundational platform for a new generation of ultra-sensitive, miniaturized sensors with broad applications from engineering monitoring to clinical diagnostics.

Figure 13.

Application of SM-LPFGs: for structural health monitoring, SM-LPFGs utilize engineered geometries like helical profiles for sensitive torsion and strain detection. For biochemical sensing, waveguide modification via tapering or etching is employed to intensify the evanescent field’s interaction with the surrounding analyte.

LPFG-based sensors represent one of the most extensively developed platforms for biochemical sensing [15,16], with successful demonstrations in the detection of viruses [106], gastroenteritis [111], hemoglobin [112], Staphylococcus aureus [113], Escherichia coli [114], glucose [115], and cancer biomarkers [116]. The principal advantage of LPFGs lies in their high sensitivity to the external environment. To further augment this sensitivity, structural modulations such as tapering or cladding-etching are often employed to create SM-LPFGs. Subsequent surface functionalization with biorecognition elements then facilitates the specific detection of target analytes. A key strategy involves designing the operating wavelength of structurally optimized SM-LPFGs near the DTP [117]. The dual resonant peaks in this regime exhibit a dramatic and opposing response to refractive index changes, amplifying the sensor signal by orders of magnitude to achieve exceptional physical sensitivity. This heightened physical sensitivity is then translated into specific molecular recognition by chemically modifying the fiber surface to immobilize bioreceptors, such as antibodies. This synergistic approach, combining physical structure optimization with surface chemistry engineering, culminates in label-free biosensing platforms that offer both ultra-high sensitivity and high specificity, providing a pivotal technology for fields like clinical diagnostics and food safety.