With Blue Light against Biofilms: Berberine as Natural Photosensitizer for Photodynamic Inactivation of Human Pathogens

Abstract

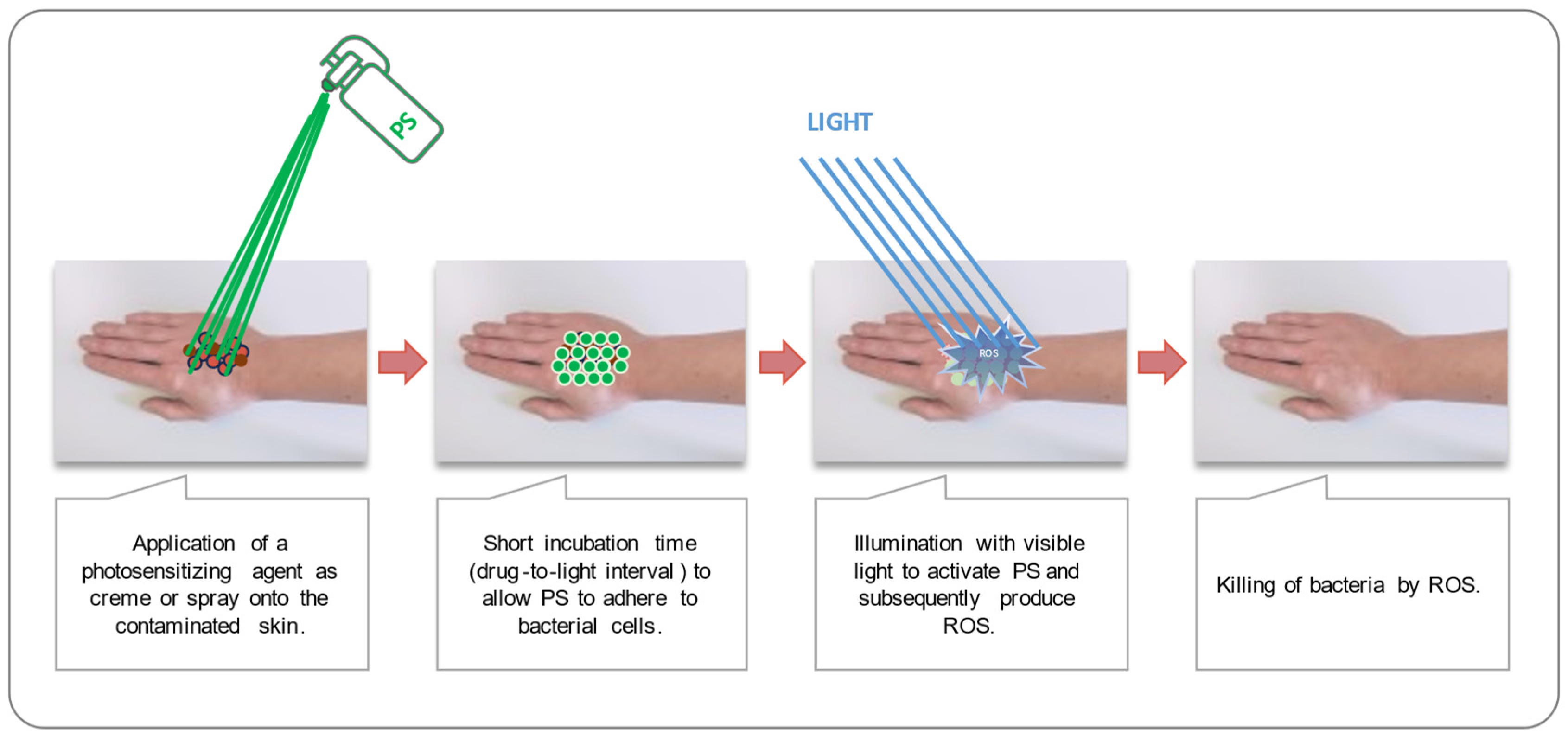

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Photosensitizer Stock Solutions

2.2. Microorganisms

2.3. Photoactivity Testing of Berberine Chloride Hydrate

2.4. Photodynamic Inactivation of Bacteria in Planktonic Culture

2.5. Photodynamic Inactivation of Bacteria Grown in Static Biofilm Formations

2.6. Data Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Photoactivity of Berberine Chloride Hydrate

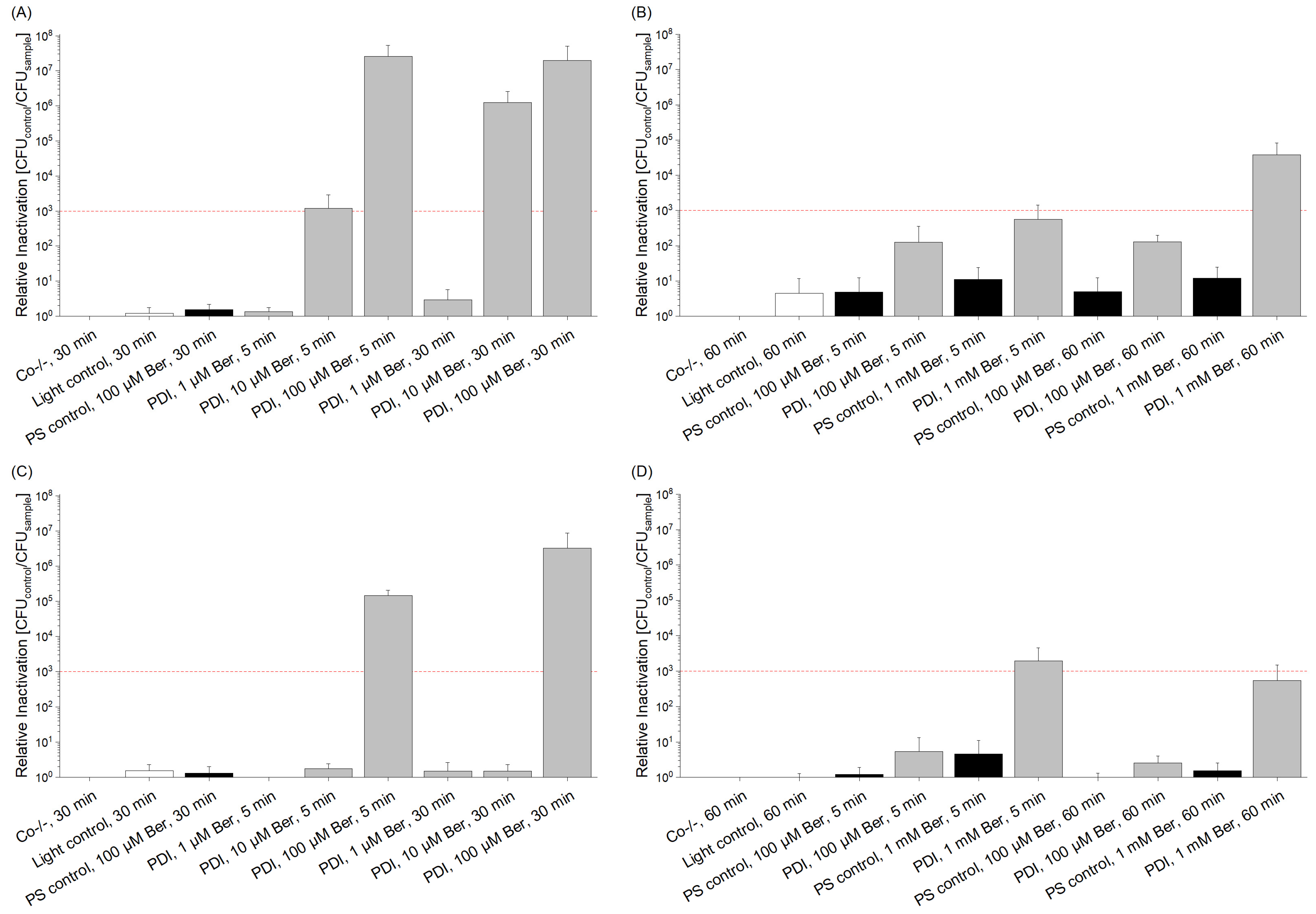

3.2. Phototoxicity of Berberine Chloride Hydrate towards Staphylococcus capitis and Staphylococcus aureus

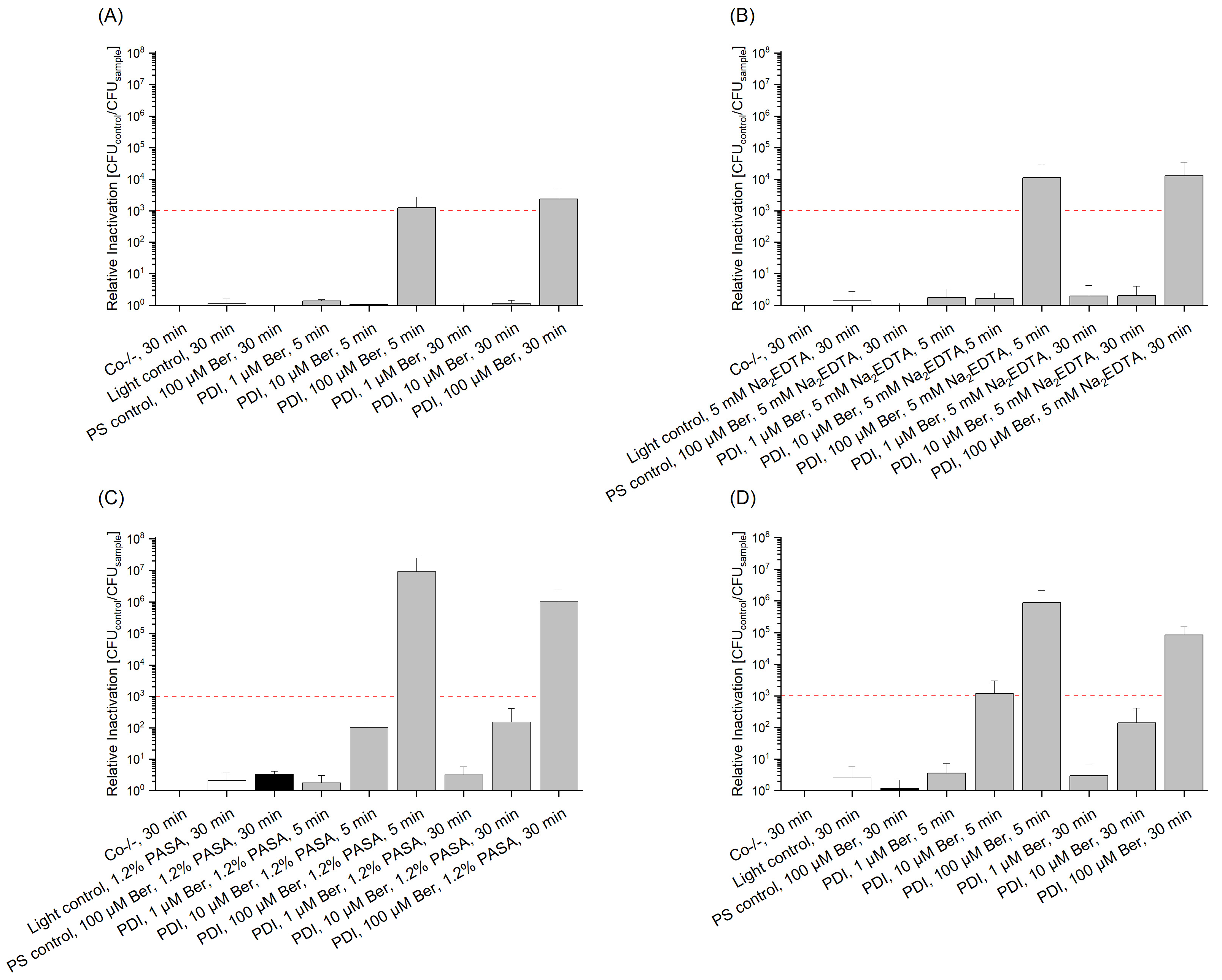

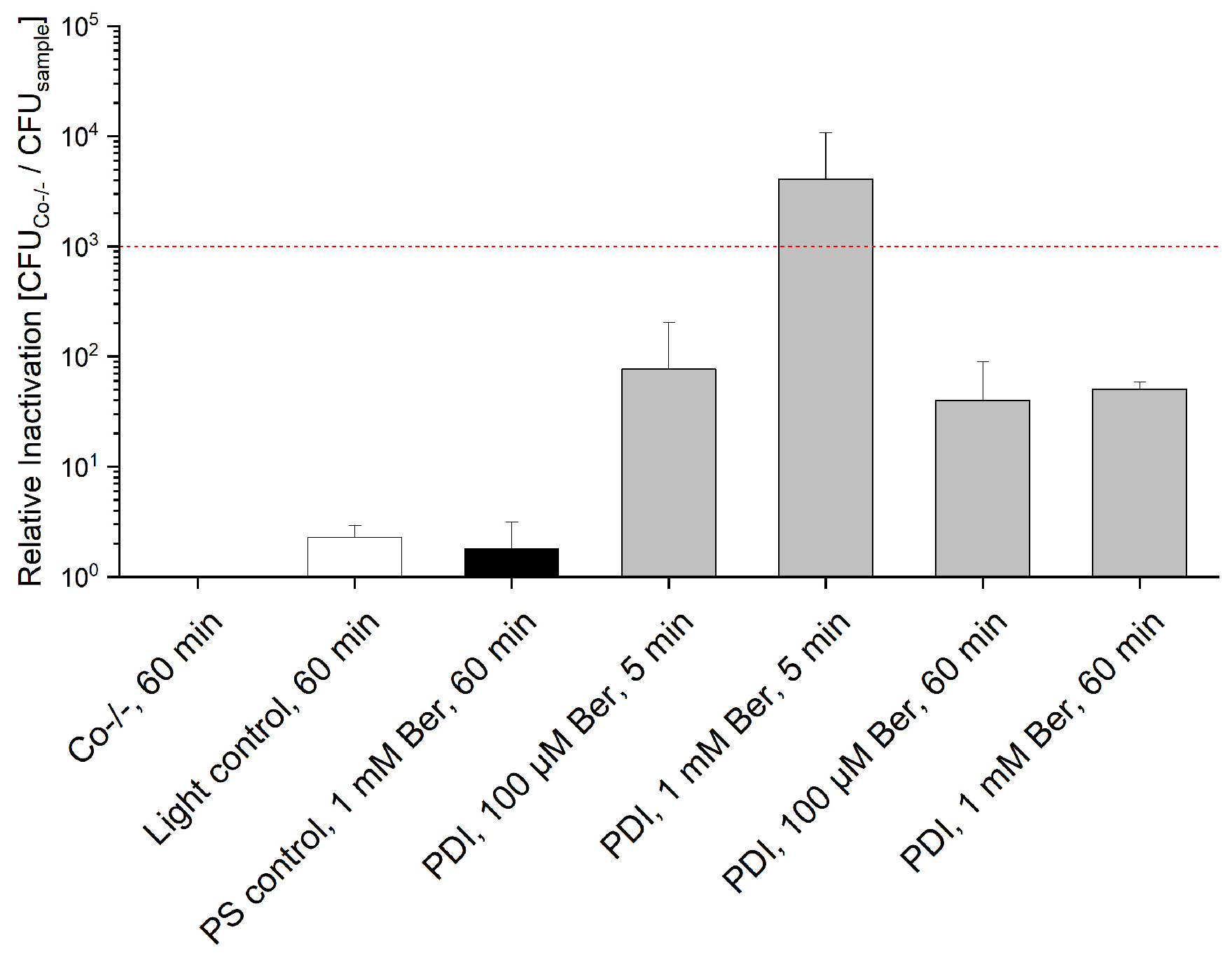

3.3. Phototoxicity of Berberine Chloride Hydrate towards Gram(−) Escherichia coli

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ber | Berberine chloride hydrate |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit(s) |

| Co−/− | Double-negative control (no light, no PS) |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| mean | Mean value |

| MG | Malachite green |

| MB | Methylene Blue |

| Na2EDTA | Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate |

| PASA | Polyaspartic acid |

| PDI | Photodynamic Inactivation |

| PS | Photosensitizer |

| PS control | Photosensitizer control (highest PS concentration, longest incubation period, no light) |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

| S. capitis | Staphylococcus capitis subsp. capitis |

| TBO | Toluidine blue O-based PS |

References

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Laxminarayan, R.; Duse, A.; Wattal, C.; Zaidi, A.K.M.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Sumpradit, N.; Vlieghe, E.; Hara, G.L.; Gould, I.M.; Goossens, H.; et al. Antibiotic resistance—The need for global solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 1057–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livermore, D.M. Antibiotic resistance in staphylococci. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2000, 16, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. 2021 Antibacterial Agents in Clinical and Preclinical Development: An Overview and Analysis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Fux, C.A.; Costerton, J.W.; Stewart, P.S.; Stoodley, P. Survival strategies of infectious biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 2005, 13, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloos, W.E.; Schleifer, K.H. Isolation and characterization of staphylococci from human skin II. descriptions of four new species: Staphylococcus warneri, Staphylococcus capitis, Staphylococcus hominis, and Staphylococcus simulans1. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1975, 25, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Kanzaki, H.; Tada, J.; Arata, J. Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolated from Various Skin Lesions. J. Dermatol. 1998, 25, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, M.E.; Fey, P.D. Staphylococcus epidermidis and other coagulase-negative staphylococci. In Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 2579–2589. [Google Scholar]

- Szczuka, E.; Jabłońska, L.; Kaznowski, A. Coagulase-negative staphylococci: Pathogenesis, occurrence of antibiotic resistance genes and in vitro effects of antimicrobial agents on biofilm-growing bacteria. J. Med. Microbiol. 2016, 65, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessa, G. Bacterial Infections. In Dermatology in Public Health Environments: A Comprehensive Textbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- McConoughey, S.J.; Howlin, R.; Granger, J.F.; Manring, M.M.; Calhoun, J.H.; Shirtliff, M.; Kathju, S.; Stoodley, P. Biofilms in periprosthetic orthopedic infections. Future Microbiol. 2014, 9, 987–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, M.; Monteiro, F.J.; Ferraz, M.P. Infection of orthopedic implants with emphasis on bacterial adhesion process and techniques used in studying bacterial-material interactions. Biomatter 2012, 2, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z.; Ladan, H.; Nitzan, Y. Photodynamic inactivation of Gram-negative bacteria: Problems and possible solutions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1992, 14, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.A.; Aftab, A.; Riffat, M. Nosocomial infections and their control strategies. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 505–509. [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright, M.; Maisch, T.; Nonell, S.; Plaetzer, K.; Almeida, A.; Tegos, G.P.; Hamblin, M.R. Photoantimicrobials—Are we afraid of the light? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e49–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, R.; Zaat, S.A.J.; Breukink, E.; Heger, M. Antibacterial photodynamic therapy: Overview of a promising approach to fight antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2015, 1, 140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abrahamse, H.; Hamblin, M.R. New photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Ji, H.-F. The mechanisms of ROS-photogeneration by berberine, a natural isoquinoline alkaloid. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2010, 99, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Feng, X.; Chai, L.; Cao, S.; Qiu, F. The metabolism of berberine and its contribution to the pharmacological effects. Drug Metab. Rev. 2017, 49, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasa, K.; Lee, D.-U.; Kang, S.-I.; Wiegrebe, W. Antimicrobial activity of 8-alkyl-and 8-phenyl-substituted berberines and their 12-bromo derivatives. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 1150–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.; Wei, J.; Abidi, P.; Lin, M.; Inaba, S.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Si, S.; Pan, H.; et al. Berberine is a novel cholesterol-lowering drug working through a unique mechanism distinct from statins. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 1344–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kakkar, P. Antihyperglycemic and antioxidant effect of Berberis aristata root extract and its role in regulating carbohydrate metabolism in diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 123, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, R.-G.; Huang, S.-Y.; Wu, S.-X.; Zhou, D.-D.; Yang, Z.-J.; Saimaiti, A.; Zhao, C.-N.; Shang, A.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Gan, R.-Y.; et al. Anticancer effects and mechanisms of berberine from medicinal herbs: An update review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battu, S.K.; Repka, M.A.; Maddineni, S.; Chittiboyina, A.G.; Avery, M.A.; Majumdar, S. Physicochemical characterization of berberine chloride: A perspective in the development of a solution dosage form for oral delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2010, 11, 1466–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, K.; Hirano, T. The microenvironment of DNA switches the activity of singlet oxygen generation photosensitized by berberine and palmatine. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glueck, M.; Schamberger, B.; Eckl, P.; Plaetzer, K. New horizons in microbiological food safety: Photodynamic Decontamination based on a curcumin derivative. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 1784–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, R.; Steigbigel, R.T.; Davis, H.T.; Chapman, S.W. Method of reliable determination of minimal lethal antibiotic concentrations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1980, 18, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernerd, F.; Passeron, T.; Castiel, I.; Marionnet, C. The damaging effects of long UVA (UVA1) rays: A major challenge to preserve skin health and integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sage, E.; Girard, P.-M.; Francesconi, S. Unravelling UVA-induced mutagenesis. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012, 11, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaetzer, K.; Krammer, B.; Berlanda, J.; Berr, F.; Kiesslich, T. Photophysics and photochemistry of photodynamic therapy: Fundamental aspects. Lasers Med. Sci. 2009, 24, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyabe, M.; Junqueira, J.C.; da Costa, A.C.B.P.; Jorge, A.O.C.; Ribeiro, M.S.; Feist, I.S. Effect of photodynamic therapy on clinical isolates of Staphylococcus spp. Braz. Oral Res. 2011, 25, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karner, L.; Drechsler, S.; Metzger, M.; Hacobian, A.; Schädl, B.; Slezak, P.; Grillari, J.; Dungel, P. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy fighting polymicrobial infections—A journey from in vitro to in vivo. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehler, D.; Brandl, E.; Hiller, K.-A.; Cieplik, F.; Maisch, T. Membrane damage as mechanism of photodynamic inactivation using Methylene blue and TMPyP in Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2022, 21, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Zekker, I.; Zhang, B.; Hendi, A.H.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, S.; Zada, N.; Ahmad, H.; Shah, L.A.; et al. Review on methylene blue: Its properties, uses, toxicity and photodegradation. Water 2022, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, K.B.P.; Raimundo, A.F.G.; Klosowski, E.M.; de Souza, B.T.L.; Mito, M.S.; Constantin, R.P.; Mantovanelli, G.C.; Mewes, J.M.; Bizerra, P.F.V.; da Costa Menezes, P.V.M.; et al. Toluidine blue O directly and photodynamically impairs the bioenergetics of liver mitochondria: A potential mechanism of hepatotoxicity. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2023, 22, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasenleitner, M.; Plaetzer, K. In the right light: Photodynamic inactivation of microorganisms using a LED-based illumination device tailored for the antimicrobial application. Antibiotics 2019, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safai, S.M.; Khorsandi, K.; Falsafi, S. Effect of Berberine and Blue LED Irradiation on Combating Biofilm of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glueck, M.; Hamminger, C.; Fefer, M.; Liu, J.; Plaetzer, K. Save the crop: Photodynamic Inactivation of plant pathogens I: Bacteria. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2019, 18, 1700–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heesterbeek, D.A.; Muts, R.M.; van Hensbergen, V.P.; Aulaire, P.d.S.; Wennekes, T.; Bardoel, B.W.; van Sorge, N.M.; Rooijakkers, S.H.M. Outer membrane permeabilization by the membrane attack complex sensitizes Gram-negative bacteria to antimicrobial proteins in serum and phagocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandio, F.F.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Hamblin, R.M. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy to Kill Gram-negative Bacteria. Recent Pat. Anti-Infect. Drug Discov. 2013, 8, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.D.; Phasupan, P.; Nguyen, L.T. Antimicrobial photodynamic efficacy of selected natural photosensitizers against food pathogens: Impacts and interrelationship of process parameters. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 32, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luksienė, Z.; Zukauskas, A. Prospects of photosensitization in control of pathogenic and harmful micro-organisms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, S.F.G.; Junqueira, J.C.; Barbosa, J.O.; Majewski, M.; Munin, E.; Jorge, A.O.C. Photodynamic inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli biofilms by malachite green and phenothiazine dyes: An in vitro study. Arch. Oral Biol. 2012, 57, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacteria | Life Form | Concentration of Ber | Additive | Drug-to-Light Interval [min] | Radiant Exposure [J/cm2] | Relative Inactivation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. capitis | planktonic | 100 µM | - | 5 | 25 | 7 log10 |

| biofilm | 1 mM | - | 60 | 100 | 4 log10 | |

| S. aureus | planktonic | 100 µM | - | 30 | 25 | 6 log10 |

| biofilm | 1 mM | - | 5 | 100 | 3 log10 | |

| E. coli | planktonic | 100 µM | 1.2% PASA | 5 | 25 | 7 log10 |

| biofilm | 1 mM | - | 5 | 100 | 3 log10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wimmer, A.; Glueck, M.; Liu, J.; Fefer, M.; Plaetzer, K. With Blue Light against Biofilms: Berberine as Natural Photosensitizer for Photodynamic Inactivation of Human Pathogens. Photonics 2024, 11, 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics11070647

Wimmer A, Glueck M, Liu J, Fefer M, Plaetzer K. With Blue Light against Biofilms: Berberine as Natural Photosensitizer for Photodynamic Inactivation of Human Pathogens. Photonics. 2024; 11(7):647. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics11070647

Chicago/Turabian StyleWimmer, Annette, Michael Glueck, Jun Liu, Michael Fefer, and Kristjan Plaetzer. 2024. "With Blue Light against Biofilms: Berberine as Natural Photosensitizer for Photodynamic Inactivation of Human Pathogens" Photonics 11, no. 7: 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics11070647

APA StyleWimmer, A., Glueck, M., Liu, J., Fefer, M., & Plaetzer, K. (2024). With Blue Light against Biofilms: Berberine as Natural Photosensitizer for Photodynamic Inactivation of Human Pathogens. Photonics, 11(7), 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics11070647