Fish Communities and Management Challenges in Three Ageing Tropical Reservoirs in Southwestern Nigeria

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

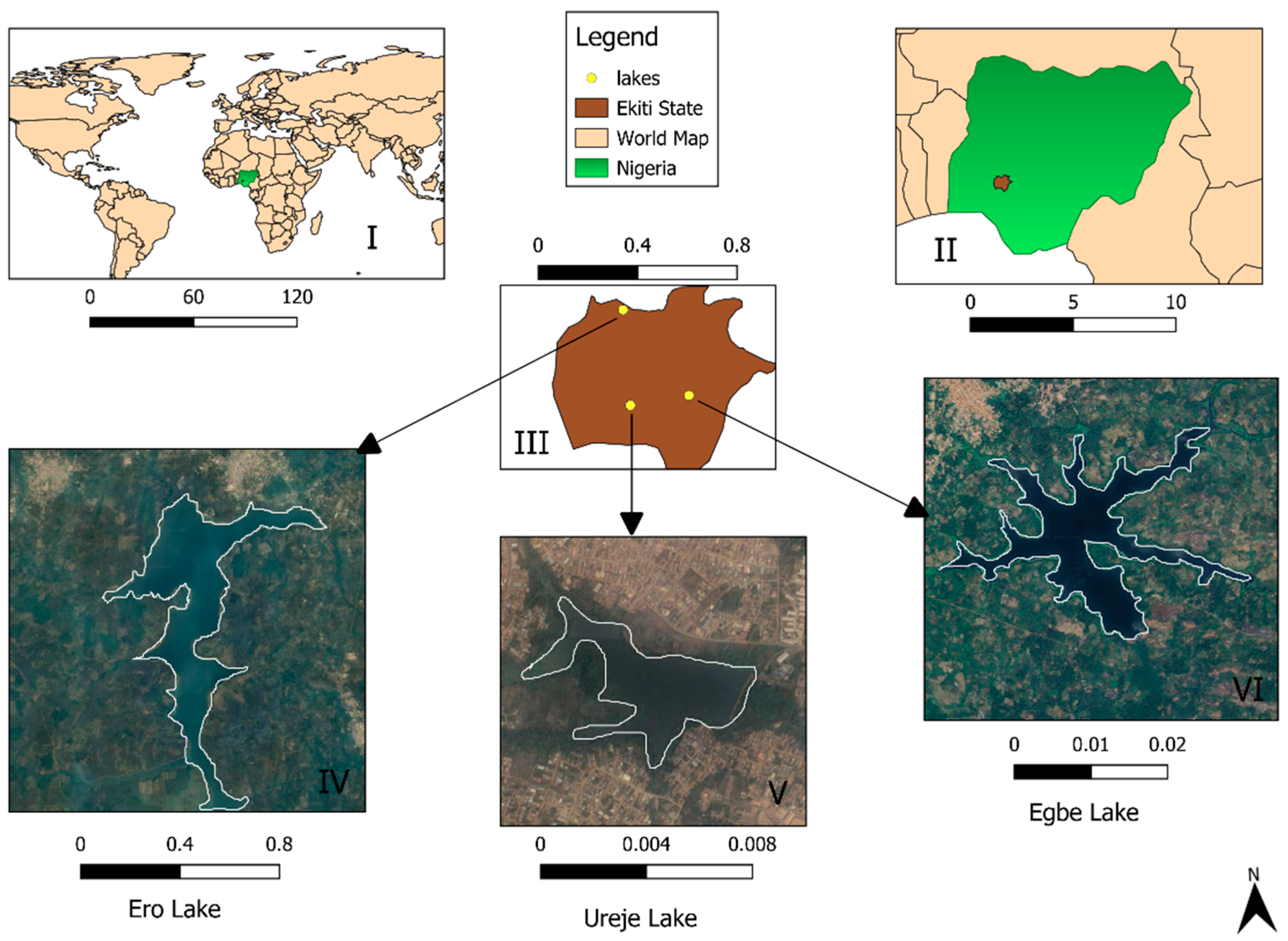

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Estimation of Species Diversity

2.3.1. Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index (H′)

2.3.2. Simpson’s Index

2.3.3. Species Equitability Index

2.3.4. Margalef’s Diversity Index

2.4. Catch Density

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Water Quality Parameters

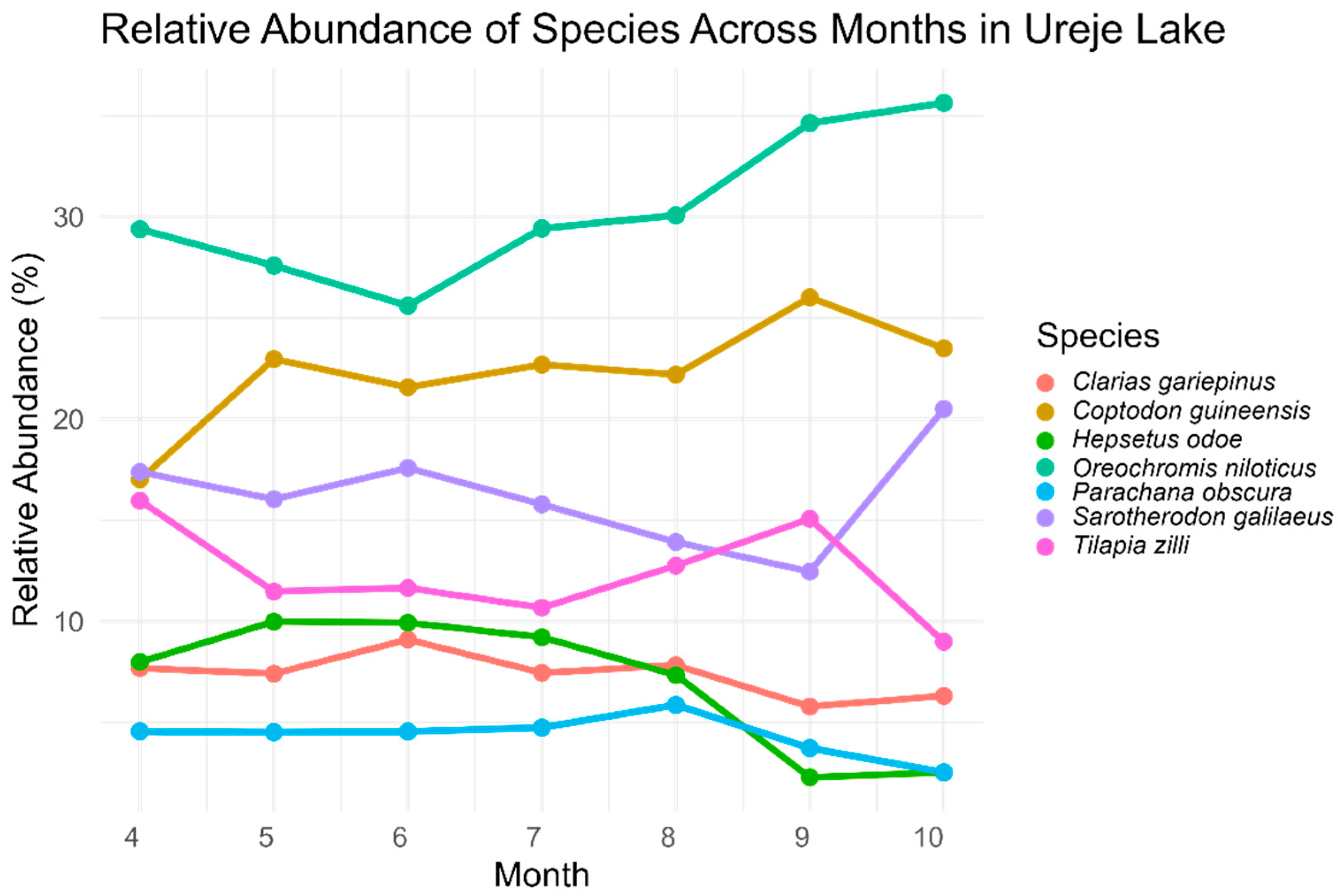

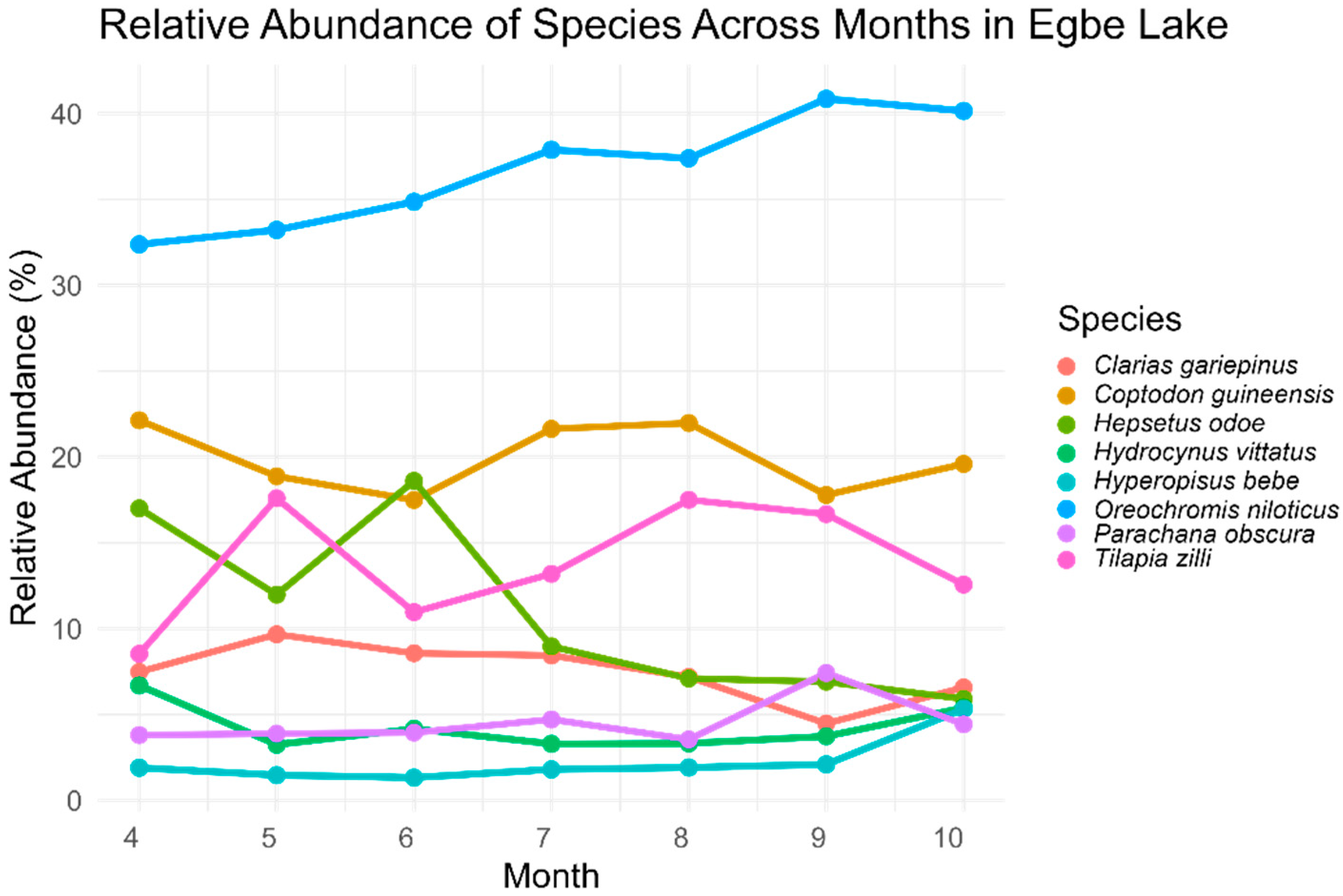

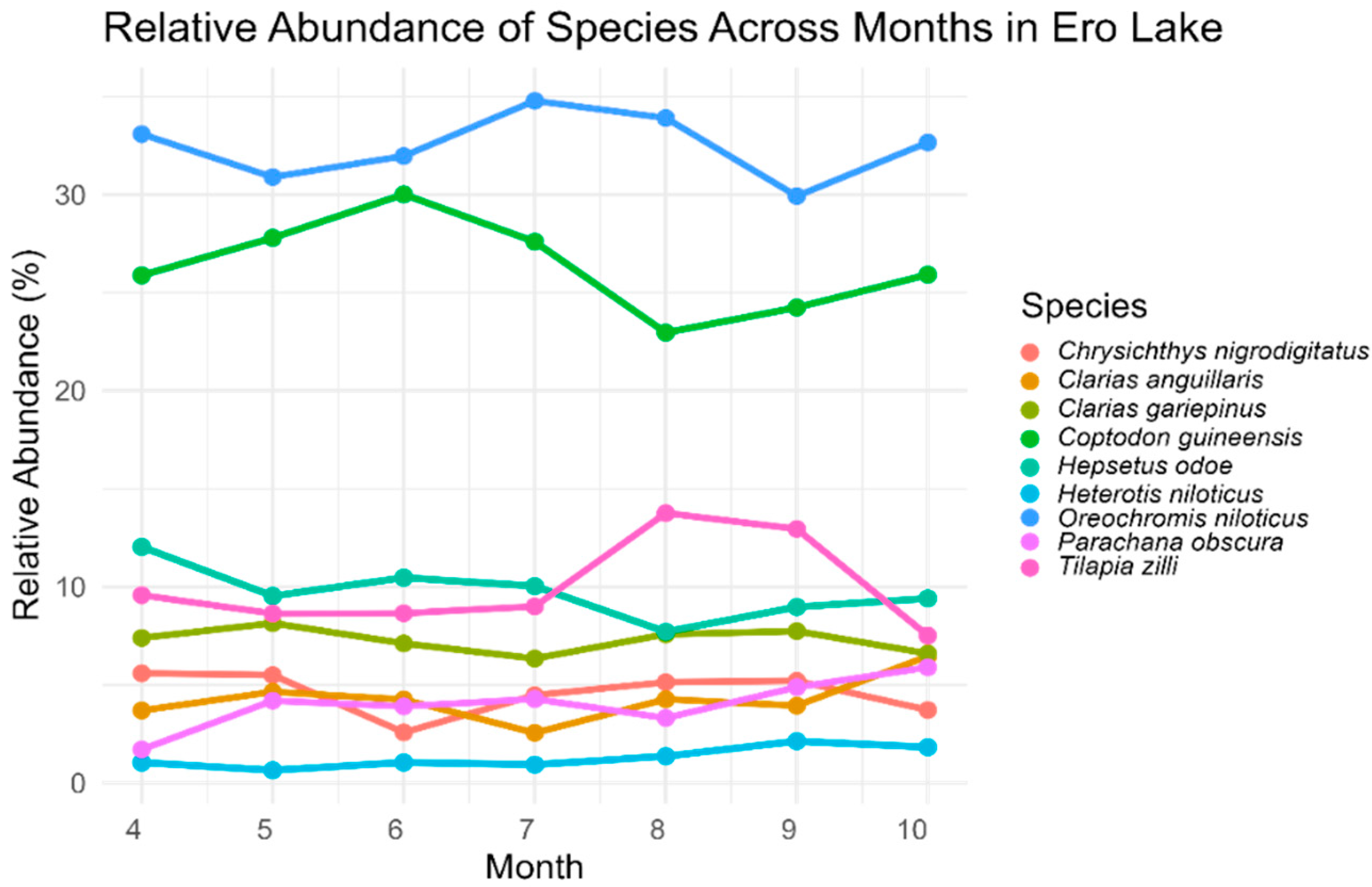

3.2. Fish Catch and Relative Abundance

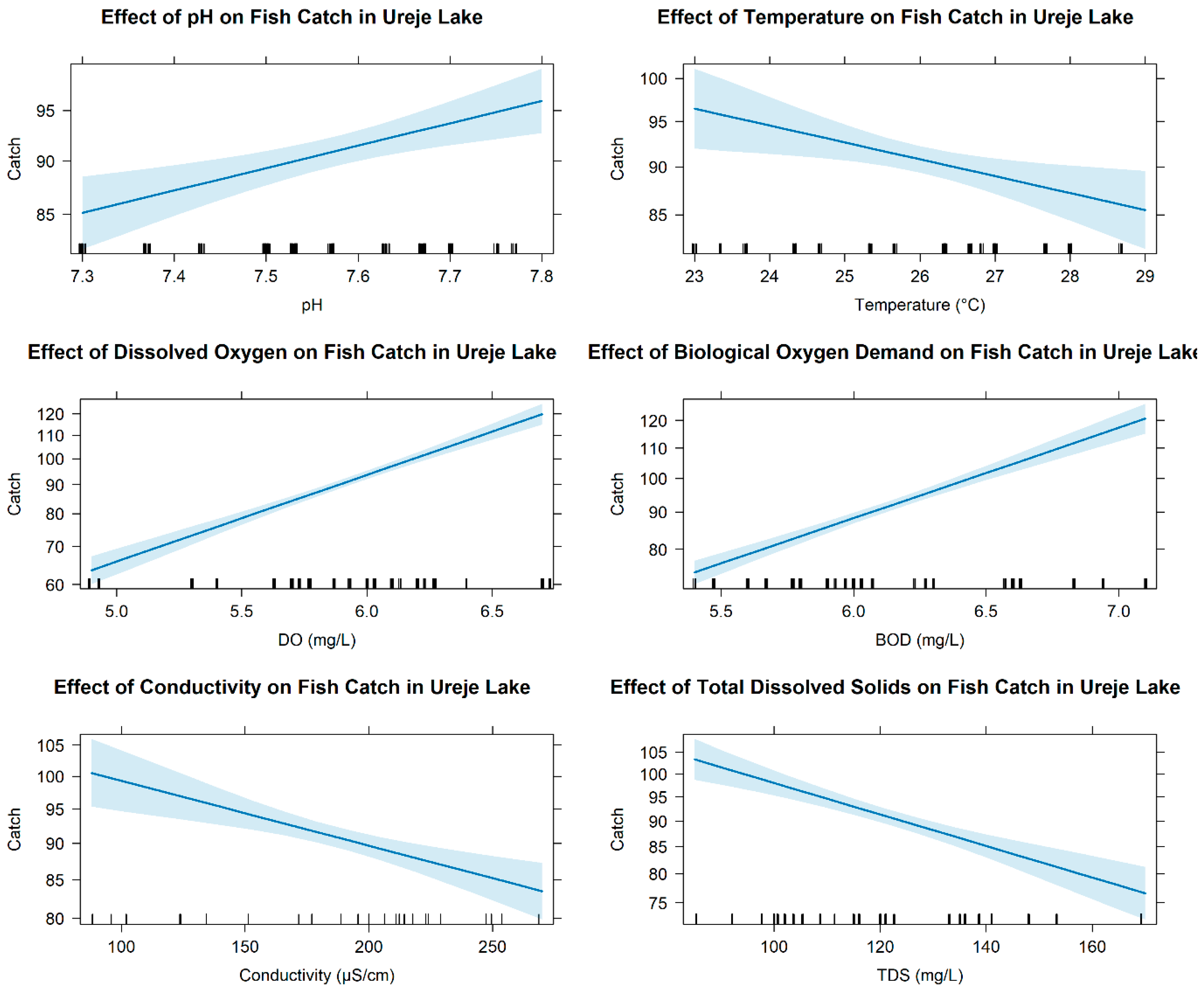

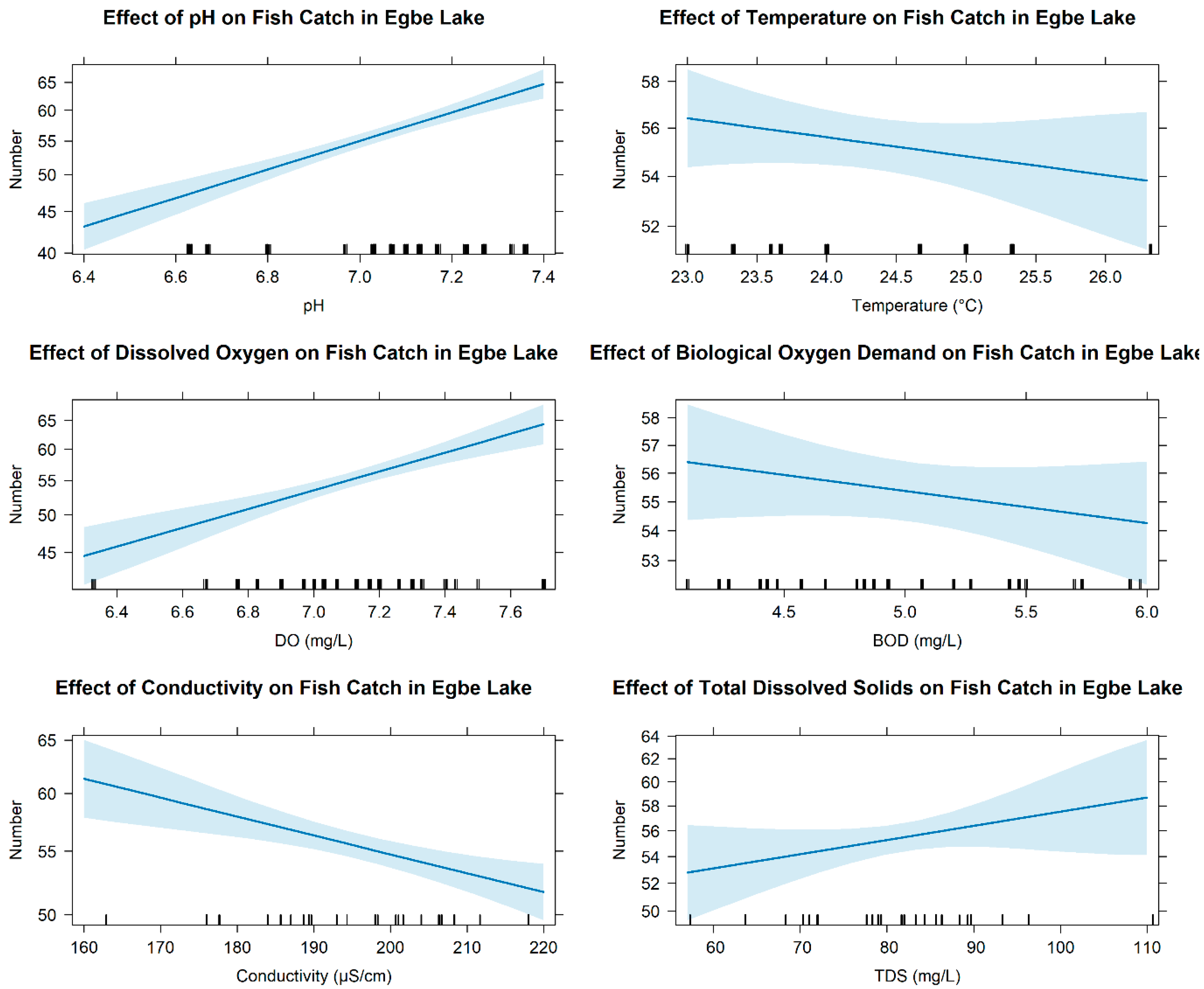

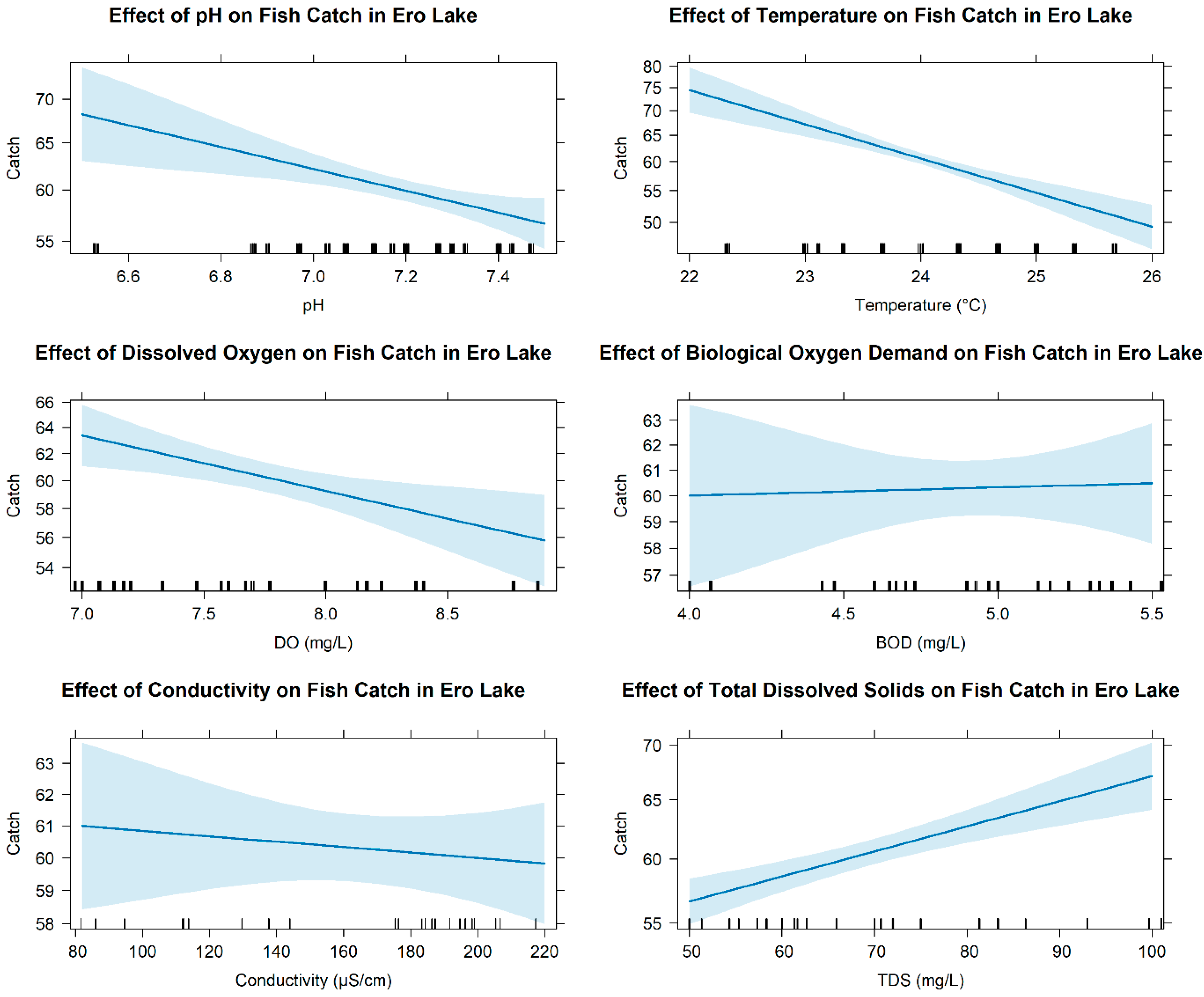

3.3. Relationship Between Abundance of Fish Fauna and Environmental Variables

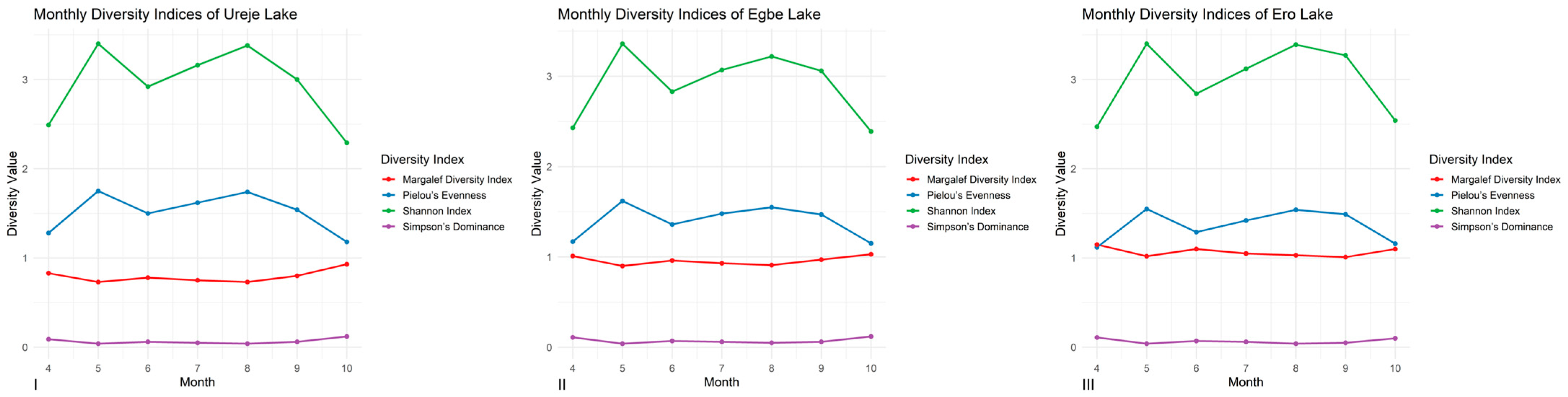

3.4. Diversity Indices

3.5. Catch DensityReport

3.6. Local Insights and Ecological Knowledge

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental Suitability and Differential Drivers of Fish Persistence

4.2. Fish Assemblages: Stability, Dominance, and Conservation Significance

4.3. Anthropogenic Pressure, Governance Deficits, and Threats to Conservation Value

4.4. Functional Integrity and Trophic Structure

5. Practical Management Recommendations Derived from the Study

- Introduce compulsory catch and effort reporting systems.

- 2.

- Adopt reservoir specific fishing regulations that reflect ecological and exploitation patterns.

- 3.

- Establish formal co-management committees to address governance gaps.

- 4.

- Integrate fishers’ ecological knowledge into monitoring and adaptive decision making.

- 5.

- Incorporate environmental DNA metabarcoding into biodiversity monitoring.

- 6.

- Integrate catchment protection and water quality management into reservoir governance frameworks.

- 7.

- Officially recognize the reservoirs in state fisheries and biodiversity plans

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brondízio, E.S.; Settele, J.; Díaz, S.; Ngo, H.T. The Global Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES): Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. Living Planet Report 2024—A System in Peril; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kolding, J.; van Zwieten, P.A.M. Relative Lake Level Fluctuations and Their Influence on Productivity and Resilience in Tropical Lakes and Reservoirs. Fish. Res. 2012, 115–116, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagbemide, P.T.; Owolabi, O.D. Length-Weight Relationship and Condition Factor of Oreochromis Niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Selected Tropical Reservoirs of Ekiti State, Southwest Nigeria. J. Exp. Biol. Agric. Sci. 2023, 11, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius, O.T.; Zangaro, F.; Massaro, R.; Marcucci, F.; Cazzetta, A.; Sangiorgio, F.; Olasunkanmi, J.B.; Specchia, V.; Julius, O.O.; Rosati, I.; et al. Assessing Fish Populations Through Length–Weight Relationships and Condition Factors in Three Lakes of Nigeria. Biology 2025, 14, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebola, T.O.; Bello Olusoji, O.A.; Fagbenro, A.O.; Sabejeje, T.A. Length Weight Relationship and Condition Factor of Four Commercially Important Fish Species at ERO Reservoir, Ekiti State, Nigeria. Int. J. Inov. Res. Dev. 2016, 5, 101432. [Google Scholar]

- Olagbemide, P.T.; Owolabi, O.D. Metal Accumulation in Ekiti State’s Three Major Dams’ Water and Sediments, the Ecological Hazards Assessment and Consequences on Human Health. J. Exp. Biol. Agric. Sci. 2023, 11, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awogbami, O.S.; Ogundiran, M.A.; Ayandiran, T.A.; Fawole, O.O.; Adedokun, M.A.; Durodola, F.A.; Balogun, H.A.; Ishola, O.A.; Adebayo, P.; Olanipekun, A.S.; et al. Quality Assessment of Water, Nutritional Fitness and Parasitic Status of Three Selected Fish Species in Ero Dam, Nigeria. J. Surv. Fish. Sci 2024, 11, 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- Adubiaro, H.O.; Animashaun, S.A. Levels of Some Heavy Metals in Fish Organs from Egbe Dam, Ekiti State, Nigeria. Riv. Ital. Delle Sostanze Grasse 2021, 98, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Haruna, K.; Adamu, I. Frame and Catch Assessment Surveys of the Fisheries of Egbe Reservoir, Ekiti State, Nigeria. Bull. Environ. Sci. Sustain. Manag. 2023, 7, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward, J.B.; Agunbiade, R.O.; Falade, J. Influence of Land-Use Pattern on Ureje Reservoir, Ado-Ekiti, Southwestern Nigeria. Am. J. Life Sci. Spec. Issue: Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 5, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Theory of Mathematical Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1949, 27, 379–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of Diversity. Nature 1949, 163, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielou, E.C. The Measurement of Diversity in Different Types of Biological Collections. J. Theor. Biol. 1966, 13, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A. Estimating the Population Size for Capture-Recapture Data with Unequal Catchability. Biometrics 1987, 43, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, A.A.; Pelicice, F.M.; Gomes, L.C. Dams and the Fish Fauna of the Neotropical Region: Impacts and Management Related to Diversity and Fisheries. Braz. J. Biol. 2008, 68, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, M.T.; Piana, P.A.; Baumgartner, G.; Gomes, L.C. Storage or Run-of-River Reservoirs: Exploring the Ecological Effects of Dam Operation on Stability and Species Interactions of Fish Assemblages. Environ. Manag. 2020, 65, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, C.M.; Frota, A.; Ganassin, M.J.M.; Agostinho, A.A.; Gomes, L.C. Do River Basins Influence the Composition of Functional Traits of Fish Assemblages in Neotropical Reservoirs? Braz. J. Biol. 2021, 81, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; WHO. Safety and Quality of Water Used in the Production and Processing of Fish and Fishery Products; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, N.C.L.; de Santana, H.S.; Ortega, J.C.G.; Dias, R.M.; Stegmann, L.F.; da Silva Araújo, I.M.; Severi, W.; Bini, L.M.; Gomes, L.C.; Agostinho, A.A. Environmental Filters Predict the Trait Composition of Fish Communities in Reservoir Cascades. Hydrobiologia 2017, 802, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajagbe, S.O.; Ajagbe, R.O.; Ariwoola, O.S.; Abdulazeez, F.I.; Oyewole, O.O.; Ojubolamo, M.T.; Olomola, A.O.; Oyekan, O.O.; Oke, O.S. Diversity and Abundance of Cichlids in Ikere Gorge Reservoir, Iseyin, Oyo State, Nigeria. Zoologist 2021, 18, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komolafe, O.O.; Arawomo, G.A.O. Reproductive Strategy of Oreochromis Niloticus (Pisces: Cichlidae) in Opa Reservoir, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2007, 55, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Ma, Z.; Han, X.; Zhou, Z.; Tian, S.; Sun, B.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Spatial Heterogeneity and Methodological Insights in Fish Community Assessment: A Case Study in Hulun Lake. Biology 2025, 14, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poff, N.L.; Zimmerman, J.K.H. Ecological Responses to Altered Flow Regimes: A Literature Review to Inform the Science and Management of Environmental Flows. Freshw. Biol. 2010, 55, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olin, M.; Malinen, T.; Ruuhijärvi, J. Gillnet Catch in Estimating the Density and Structure of Fish Community—Comparison of Gillnet and Trawl Samples in a Eutrophic Lake. Fish. Res. 2009, 96, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Z.; McCormick, J. Evaluation of the Influence of Correcting for Gillnet Selectivity on the Estimation of Population Parameters. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagoudo, M.; Benhaïm, D.; Montchowui, E. Current Status and Prospects for Efficient Aquaculture of the African Bonytongue, Heterotis Niloticus (Cuvier, 1829): Review. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2025, 56, e70009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoutchi, A.I.; Kamelan, T.M.; Kargbo, A.; Gneho, D.A.D.; Kouamelan, E.P.; Mehner, T. Local Fishers’ Knowledge on the Ecology, Economic Importance, and Threats Faced by Populations of African Snakehead Fish, Parachanna Obscura, within Côte d’Ivoire Freshwater Ecosystems. Aquac. Fish Fish. 2023, 3, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogueri, C.; Anyanwu, C.N.; Adaka, G.S.; O Ajima, M.N.; Utah, C.; Nwaka, D.; Ezeafulukwe, C.F.; Oguleru, P.O.; Alabi, B.; Adebayo, E.T. Stock Status of Hepsetus Odoe (Bloch 1974) in River Imo, Nigeria, for Conservation and Management Strategies for Sustainability. Manglar 2025, 22, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souley, S.M.N.; Harouna, M.; Ado, M.I.; Youssoufa, I. Length-Weight Relationships and Condition Factors of Mormyridae Species in the Niger River: Implications for Conservation and Management. Limnol. Freshw. Biol. 2025, 2025, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, A.; Afaru, J.; Abubakar, K.A. Evaluating Fish Diversity and Distribution Patterns Across Seasons in The Lower River Benue, Nigeria. Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2025, 18, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Adaka, G.S.; Nlewadim, A.A.; Udoh, J.P. Diversity and Distribution of Freshwater Fishes in Oguta Lake, Southeast Nigeria. Adv. Life Sci. Technol. 2016, 46, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kareem, O.K.; Olanrewaju, A.N.; Orisasona, O.; Olofintila, O.O. Fish Diversity and Abundance in Ikere Gorge Reservoir, South-Western Nigeria. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Conference of Forestry Association of Nigeria (FAN), Lagos, Nigeria, 12–16 March 2018; 2020, pp. 753–758. [Google Scholar]

- Olopade, O.A.; Dienye, H.E. Management of Overfishing in the Inland Capture Fisheries in Nigeria. J. Limnol. Freshw. Fish. Res. 2017, 3, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathy, H.; Bernerd, F.; Richard, L. Africa’s Forgotten Fishes; World Wide Fund for Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund): Gland, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoade, A.A.; Adeyemi, S.A.; Ayedun, A.S. Food and Feeding Habits of Hepsetus Odoe and Polypterus Senegalus in Eleyele Lake, Southwestern Nigeria. Trop. Freshw. Biol. 2018, 27, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winemiller, K.O.; Kelso-Winemiller, L.C. Comparative Ecology of the African Pike, Hepsetus Odoe, and Tigerfish, Hydrocynus Forskahlii, in the Zambezi River Floodplain. J. Fish. Biol. 1994, 45, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, V.F.; Humber, F.; Nohasiarivelo, T.; Botosoamananto, R.; Anderson, L.G. Trialling the Use of Smartphones as a Tool to Address Gaps in Small-Scale Fisheries Catch Data in Southwest Madagascar. Mar. Policy 2019, 99, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.J.; Achieng, A.O.; Chavula, G.; Haninga Haambiya, L.; Iteba, J.; Kayanda, R.; Kaunda, E.; Ajode, M.Z.; Muvundja, F.A.; Nakiyende, H.; et al. Future Success and Ways Forward for Scientific Approaches on the African Great Lakes. J. Great Lakes Res. 2023, 49, 102242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otundo Richard, M. Strategic Innovative Community-Based Fisheries Management Practices for The Success of The Blue Economy Program in Kenya. SSRN Electron. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morand, P.; Kodio, A.; Andrew, N.; Sinaba, F.; Lemoalle, J.; Béné, C.; Morand, P.; Kodio, A.; Sinaba, F.; Andrew, N.; et al. Vulnerability and Adaptation of African Rural Populations to Hydro-Climate Change: Experience from Fishing Communities in the Inner Niger Delta (Mali). Clim. Change 2012, 115, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupika, O.L.; Gandiwa, E.; Nhamo, G.; Kativu, S. Local Ecological Knowledge on Climate Change and Ecosystem-Based Adaptation Strategies Promote Resilience in the Middle Zambezi Biosphere Reserve, Zimbabwe. Scientifica 2019, 2019, 3069254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechonge, A.H.; Collins, R.A.; Ward, S.; Saxon, A.D.; Smith, A.M.; Matiku, P.; Turner, G.F.; Kishe, M.A.; Ngatunga, B.P.; Genner, M.J. Environmental DNA Metabarcoding Details the Spatial Structure of a Diverse Tropical Fish Assemblage in a Major East African River System. Environ. DNA 2024, 6, e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleman, P.J.; Durand, J.D.; Simier, M.; Camará, A.; Sá, R.M.; Panfili, J. EDNA-Based Seasonal Monitoring Reveals Fish Diversity Patterns in Mangrove Habitats of Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 82, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nneji, L.M.; Oladipo, S.O.; Nneji, I.C.; Atofarati, O.T.; Asiamah, M.K.; Adelakun, K.M. Evaluating EDNA Metabarcoding for Fish Biodiversity Assessment in Nigerian Aquatic Ecosystems: Potential, Limitations, and Comparisons with Traditional Methods. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2025, 40, 2541689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| UREJE LAKE | EGBE LAKE | ERO LAKE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | |

| pH | 7.2–7.9 | 7.57 ± 0.18 | 6.3–7.5 | 7.02 ± 0.27 | 6.3–7.5 | 7.17 ± 0.21 |

| Temperature (°C) | 22–29 | 25.96 ± 1.65 | 22–27 | 24.32 ± 1.05 | 22–26 | 24.05 ± 0.93 |

| O2 (mg/L) | 4.7–7.4 | 5.91 ± 0.50 | 6.2–8.2 | 7.13 ± 0.38 | 6.8–9.1 | 7.74 ± 0.58 |

| BOD (mg/L) | 5.1–7.3 | 6.10 ± 0.54 | 4–6.6 | 5.02 ± 0.66 | 3.7–6.2 | 4.92 ± 0.53 |

| Conductivity (μS/cm) | 81–283 | 189.04 ± 52.31 | 158–231 | 196.09 ± 17.53 | 77–243 | 165.09 ± 43.73 |

| TDS (mg/L) | 79–189 | 123.03 ± 25.68 | 42–121 | 80.73 ± 13.72 | 39–108 | 68.29 ± 17.06 |

| S/N | Order | Family | Scientific Name | Lake Found | Feeding Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cichliformes | Cichlidae | Oreochromis niloticus * | Ureje, Egbe, Ero | Herbivore |

| 2 | Cichliformes | Cichlidae | Tilapia zilli * | Ureje, Egbe, Ero | Herbivore |

| 3 | Cichliformes | Cichlidae | Coptodon guineensis * | Ureje, Egbe, Ero | Herbivore |

| 4 | Cichliformes | Cichlidae | Sarotherodon galilaeus | Ureje | Herbivore |

| 5 | Hepsetiformes | Hepsetidae | Hepsetus odoe * | Ureje, Egbe, Ero | Carnivore |

| 6 | Anabantiformes | Channidae | Parachanna obscura * | Ureje, Egbe, Ero | Carnivore |

| 7 | Characiformes | Alestidae | Hydrocynus vittatus | Egbe | Carnivore |

| 8 | Osteoglossiformes | Mormyridae | Hyperopisus bebe | Egbe | Omnivore |

| 9 | Osteoglossiformes | Arapaimidae | Heterotis niloticus * | Ero | Herbivore |

| 10 | Siluriformes | Clariidae | Clarias gariepinus * | Ureje, Egbe, Ero | Omnivore |

| 11 | Siluriformes | Clariidae | Clarias anguillaris * | Ero | Omnivore |

| 12 | Siluriformes | Claroteidae | Chrysichthys nigrodigitatus * | Ero | Omnivore |

| Family | Species | Total Catch Species | Relative Abundance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clariidae | Clarias gariepinus | 1217 | 7.53 |

| Cichlidae | Coptodon guineensis | 3625 | 22.44 |

| Oreochromis niloticus * | 4760 | 29.46 | |

| Sarotherodon galilaeus | 2525 | 15.63 | |

| Tilapia zilli | 1988 | 12.30 | |

| Hepsetidae | Hepsetus odoe | 1284 | 7.95 |

| Channidae | Parachanna obscura | 758 | 4.69 |

| Total | 16,157 | 100 |

| Family | Species | Total Catch Species | Relative Abundance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clariidae | Clarias gariepinus | 819 | 7.34 |

| Cichlidae | Coptodon guineensis | 3234 | 28.99 |

| Oreochromis niloticus * | 3666 | 32.86 | |

| Tilapia zilli | 1317 | 11.80 | |

| Hepsetidae | Hepsetus odoe | 963 | 8.63 |

| Alestidae | Hydrocynus vittatus | 449 | 4.02 |

| Mormyridae | Hyperopisus bebe | 310 | 2.78 |

| Channidae | Parachanna obscura | 399 | 3.58 |

| Total | 11,157 | 100 |

| Family | Species | Total Catch | Relative Abundance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bagridae | Chrysichthys nigrodigitatus | 643 | 4.74 |

| Clariidae | Clarias anguillaris | 570 | 4.20 |

| Clarias gariepinus | 1000 | 7.37 | |

| Cichlidae | Tilapia zilli | 1417 | 10.44 |

| Oreochromis niloticus * | 4382 | 32.28 | |

| Coptodon guineensis | 3539 | 26.07 | |

| Hepsetidae | Hepsetus odoe | 1283 | 9.45 |

| Osteoglossidae | Heterotis niloticus | 179 | 1.32 |

| Channidae | Parachanna obscura | 563 | 4.15 |

| Total | 13,576 | 100 |

| Site | H | S | J | MDI | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ureje Lake | 2.95 ± 0.42 | 7 | 1.52 ± 0.22 | 0.79 ± 0.07 | 0.07 ± 0.03 |

| Egbe Lake | 2.91 ± 0.38 | 8 | 1.4 ± 0.18 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.03 |

| Ero Lake | 3.00 ± 0.39 | 9 | 1.37 ± 0.18 | 1.07 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.03 |

| Catch Density (ha−1) | |

|---|---|

| Ureje Lake | 68.46 |

| Egbe lake | 18.91 |

| Ero Lake | 11.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Julius, O.T.; Zangaro, F.; Massaro, R.; Rainò, M.; Marcucci, F.; Cazzetta, A.; Sangiorgio, F.; Olasunkanmi, J.B.; Specchia, V.; Julius, O.O.; et al. Fish Communities and Management Challenges in Three Ageing Tropical Reservoirs in Southwestern Nigeria. Limnol. Rev. 2026, 26, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/limnolrev26010002

Julius OT, Zangaro F, Massaro R, Rainò M, Marcucci F, Cazzetta A, Sangiorgio F, Olasunkanmi JB, Specchia V, Julius OO, et al. Fish Communities and Management Challenges in Three Ageing Tropical Reservoirs in Southwestern Nigeria. Limnological Review. 2026; 26(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/limnolrev26010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleJulius, Olumide Temitope, Francesco Zangaro, Roberto Massaro, Marco Rainò, Francesca Marcucci, Armando Cazzetta, Franca Sangiorgio, John Bunmi Olasunkanmi, Valeria Specchia, Oluwafemi Ojo Julius, and et al. 2026. "Fish Communities and Management Challenges in Three Ageing Tropical Reservoirs in Southwestern Nigeria" Limnological Review 26, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/limnolrev26010002

APA StyleJulius, O. T., Zangaro, F., Massaro, R., Rainò, M., Marcucci, F., Cazzetta, A., Sangiorgio, F., Olasunkanmi, J. B., Specchia, V., Julius, O. O., Shauer, M., Basset, A., & Pinna, M. (2026). Fish Communities and Management Challenges in Three Ageing Tropical Reservoirs in Southwestern Nigeria. Limnological Review, 26(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/limnolrev26010002