Abstract

This study addresses the technical challenges of conventional coal slurry sedimentation equipment in handling fine coal particles, such as poor settling performance and strong dependence on chemical reagents, by designing a novel high-gravity sedimentation and dewatering device. Solid–liquid centrifugal separation was simulated on the CFD-Fluent platform using the Eulerian–Eulerian method, with the solid volume fraction and effective deposition thickness adopted as key indicators of particle settling performance. The settling behavior and flow field characteristics of particles with different sizes (0.045–0.5 mm) were elucidated under varying centrifugal radii (400–800 mm) and rotational speeds (400–1200 r·min−1), thereby providing a solid theoretical foundation for the parameter optimization of centrifugal settling processes for fine particles. The results indicate that increasing the centrifugal radius and rotational speed strengthens the centrifugal field effect, markedly enhancing the dynamic pressure gradient and interphase slip velocity. Under high-speed (ω = 1200 r·min−1) and large-radius (R = 800 mm) conditions, the dynamic pressure of fine particles (0.045 mm) reached 7.52 MPa with a radial velocity of 0.79 m·s−1, effectively compensating for the settling disadvantage of fine particles, promoting solid–liquid separation, and ensuring the stable deposition of coal particles. Meanwhile, as particle size increases, a distinct deposition thickness can be formed under different operating conditions, demonstrating that particle size is the dominant factor governing deposition behavior. The study elucidates the intrinsic mechanism of how multiple parameters—rotational speed, centrifugal radius, and coal particle size—synergistically influence particle deposition characteristics. By regulating these parameters to accommodate different particle sizes, the findings provide valuable insights for the parameter optimization of centrifugal settling processes for fine particles.

1. Introduction

Coal, as the dominant energy source in China, plays a pivotal role in ensuring the security and stability of energy supply [1]. According to statistics, China’s raw coal output reached 4.71 billion tons in 2023, representing a 3.4% year-on-year increase, indicate the enormous scale of coal processing and the growing demand for coal washing. Furthermore, the fact that 69% of the raw coal was subjected to washing [2], with 95.76% of it treated by the wet beneficiation processes, suggests that approximately 3.25 billion tons of raw coal required washing. However, conventional sedimentation technologies, such as natural settling and standard centrifugation, are limited by slow processing rates and low efficiency, making them inadequate for handling such massive volumes of coal slurry water [3,4,5]. Improper treatment can cause severe environmental and ecological damage and significantly reduce economic efficiency for enterprises [6,7,8]. In contrast, the advancement of high-gravity centrifugal sedimentation technology enables the efficient treatment of large volumes of high-concentration, fine-particle coal slurry water. This approach improves clean coal recovery, enhances the economic benefits of coal enterprises, reduces water consumption, and aligns with national policies on ecological and environmental protection [9]. Moreover, this technology meets the demand for large-scale and continuous treatment of coal slurry water in coal preparation plants, thereby underscoring the necessity of promoting high-gravity field sedimentation and dewatering technologies and equipment [10,11].

As coal mining becomes increasingly mechanized [12,13], the proportion of ultrafine, small-volume, negatively charged, and strongly hydrophilic mineral particles in coal slurry water has risen sharply [14,15], leading to highly dispersed suspensions and posing significant challenges to flotation recovery. These factors give coal slurry water the characteristics of large flow, high concentration, and high viscosity [16], which lead to a highly stable suspension of mineral particles and make the effective purification and utilization of coal slurry water difficult to achieve. Thus, enhancing the treatment efficiency of coal slurry water has emerged as a critical challenge in the coal preparation industry [17].

Currently, the settling and dewatering technologies and equipment used for coal slurry water primarily fall into two categories: gravity sedimentation [18,19] and centrifugal sedimentation [20]. Among them, gravity sedimentation equipment such as thickeners, filter presses, and settling tanks operates primarily based on gravitational settling for material separation. At present, gravity sedimentation technology still exhibits inherent limitations in coal slurry water treatment, thickeners and settling tanks as the equipment relies solely on gravitational force, resulting in restricted processing capacity. For the abundant fine particles present in coal slurry water, the gravitational settling velocity is extremely low. Moreover, the unit-area processing capacity of gravity sedimentation equipment is constrained by the terminal settling velocity of the particles. Increasing the treatment capacity therefore requires a larger footprint and higher reagent consumption [21,22]. Filter presses are indeed effective for dewatering fine particles; however, during coal slurry treatment, the filter cloth is prone to clogging and damage. Moreover, these systems are characterized by low processing efficiency, high equipment costs, and substantial maintenance requirements. To enhance the treatment efficiency of coal slurry water, CFD studies have been employed to optimize the internal structures of gravity sedimentation equipment, such as feed inlets and baffles, thereby improving separation performance to a certain extent. However, the fundamental physical limitations of gravity sedimentation have not been overcome by CFD studies, as the process still relies primarily on gravitational force and chemical reagents to enhance settling performance and improve treatment efficiency [23,24]. Xuetao Wang et al. investigated the settling behavior of tailings slurry in thickeners by adding thickeners [25], while Mona Akbari et al. simulated the flow characteristics of slurry at the feed inlet using the Eulerian–Eulerian approach combined with a turbulence model, and further enhanced the separation process through the application of flocculants [26,27]. Although such studies enhance equipment performance to some degree, their dependence on chemical additives (e.g., flocculants and thickeners) elevates costs and poses environmental challenges.

In contrast to gravity sedimentation, centrifugal sedimentation achieves higher efficiency in coal slurry treatment by combining centrifugal force with chemical additives. Conventional devices—such as vertical and horizontal centrifuges, spiral concentrators, and Knelson separators—intensify settling by magnifying velocity differences among particles of different densities and sizes, thereby diminishing the dependence of settling rate on particle diameter and improving overall treatment efficiency [28]. However, during the use of centrifugal sedimentation equipment, the settling velocity of fine coal particles (<0.075 mm) is substantially lower than the equipment’s processing cycle, preventing their effective capture by the centrifugal drum [29]. The discharge of substantial fine sludge with the filtrate elevates effluent turbidity and leads to issues including pipeline blockage and poor classification efficiency [30]. Meanwhile, when the slurry is fed tangentially into the centrifugal equipment by a pump, the fine particles acquire a tangential velocity in the radial position [31], thereby disturbing particle settling. The poor stability of the dynamic separation process results in non-uniform particle distribution, while local vortices cause some fine particles to be entrained and hindered from settling. Xuebin Zhang et al. analyzed the performance of the Falcon centrifuge in the separation of siliceous phosphate ore and demonstrated that mineral particles smaller than 0.045 mm could not be effectively separated and recovered [32]. P. Ginisty et al. evaluated a decanter centrifuge and reported that the complex separation mechanisms limit its effectiveness in concentrating and dewatering fine particles [33].

To overcome the high reagent demand and poor fine-particle handling of conventional gravity and centrifugal sedimentation equipment, a novel high-gravity sedimentation–dewatering device was developed. Featuring a U-shaped rotating body and central feeding, this integrated structure rotates synchronously as a whole, and the absence of internal moving parts minimizes mechanical wear and equipment damage. The design ensures uniform material distribution in the high-gravity field while eliminating tangential velocity at radial positions, thereby avoiding interference with particle settling. In contrast, conventional centrifugal equipment, such as decanter centrifuges, typically features a conical or cylindrical–conical bowl combined with an internal screw conveyor. The bowl and the conveyor rotate in the same direction at different speeds, which results in significant mechanical wear and generates strong shear forces that disrupt particle sedimentation. This study aims to investigate how different centrifugal conditions in the high-gravity sedimentation and dewatering U-shaped device influence the internal flow field and the deposition behavior of particles with varying sizes. Solid–liquid separation was simulated on the Fluent platform using the Eulerian–Eulerian method, taking solid volume fraction and effective deposition thickness (ranging from 0.95 × Packing Limit to Packing Limit) as the evaluation criterion to analyze the synergistic influence of centrifugal radius, drum speed, and feed particle size on the settling behavior of fine particles. This work elucidated the deposition behavior of fine coal particles and the evolution of the internal flow field, optimized particle settling performance, and provided a robust theoretical foundation for the design and optimization of centrifugal separation parameters.

2. Numerical Model

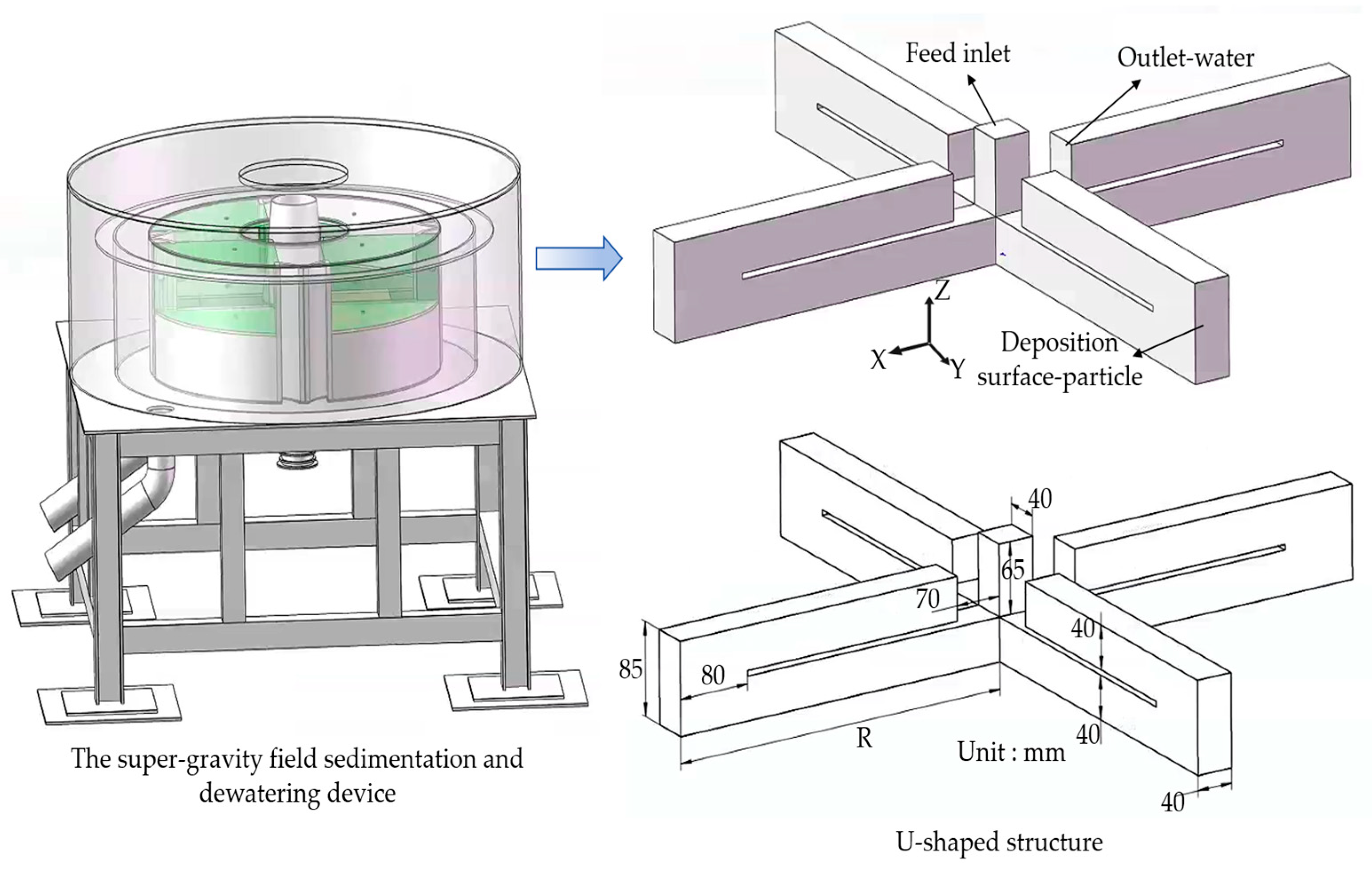

2.1. Geometry Model

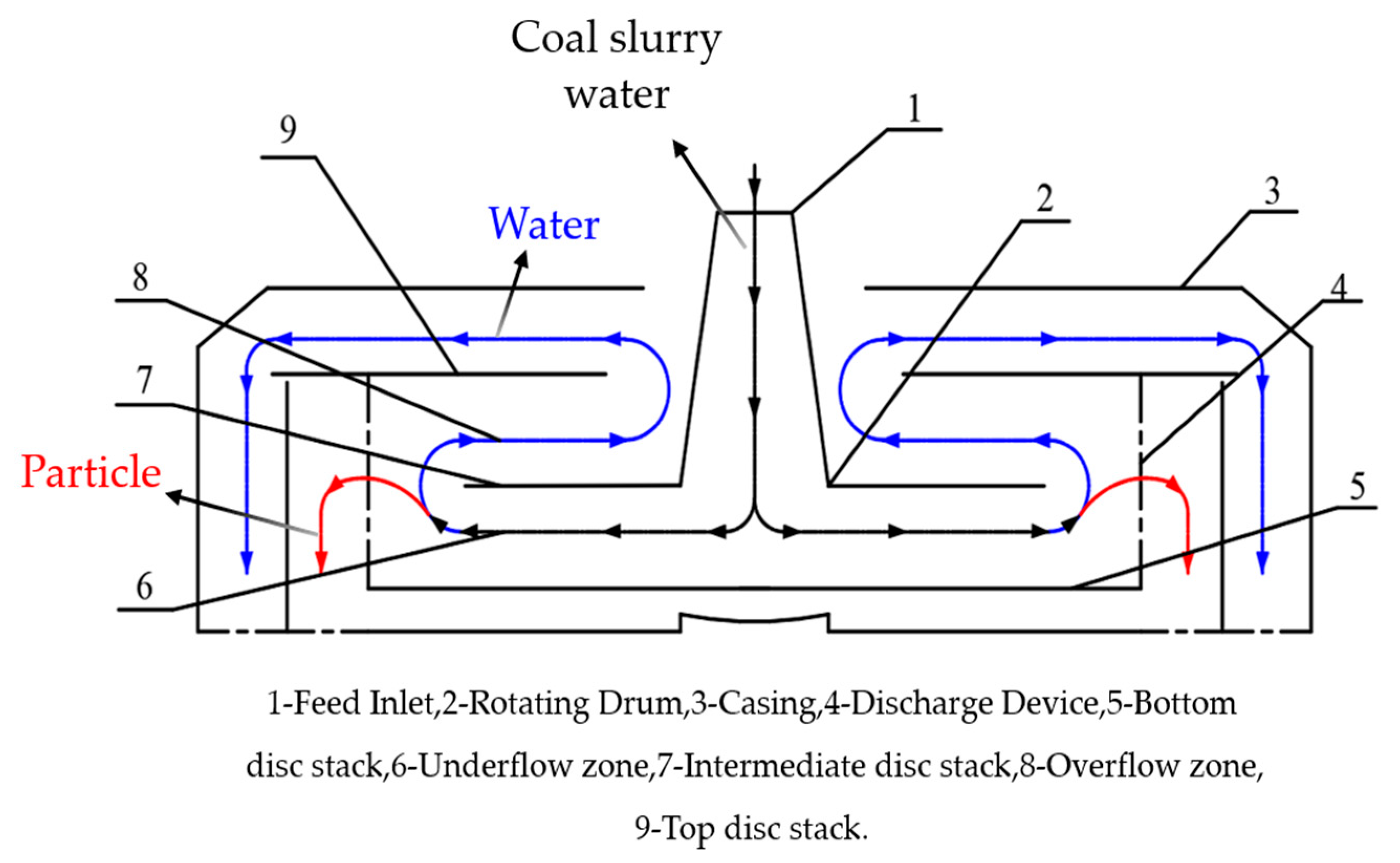

The 3D model of the high-gravity sedimentation–dewatering device with its U-shaped drum dimensions is illustrated in Figure 1. Simulations were performed under different conditions by varying the centrifugal radius (R) through parameterized models. As depicted in Figure 2, the device consists of the feed inlet, drum, casing, discharge system, and a series of discs (bottom, middle, and top) with auxiliary supports. The black curve indicates the material feeding trajectory, the red curve shows the particle settling path, and the blue curve corresponds to the water overflow trajectory. With a prescribed feed velocity, the slurry enters the drum via the feed inlet and is uniformly directed, under the high-gravity field, into four sector-shaped baffle channels evenly distributed around the bottom disc. In the rapidly rotating drum, density differences cause solid particles and water in the coal slurry to undergo unequal centrifugal forces, leading to relative motion and velocity differentials. The guide channels connecting the underflow and overflow spaces form a horizontal U-shaped tube, through which water, driven by the U-tube pressure difference, flows into the secondary chamber and exits via the overflow outlet. In contrast, solid particles are directed through the bottom channels to the baffle, where they deposit under centrifugal force, thus accomplishing centrifugal dewatering.

Figure 1.

3D model of the high-gravity sedimentation-dewatering device with U-shaped structural dimensions.

Figure 2.

Structural composition of the high-gravity sedimentation-dewatering device.

2.2. Governing Equations

- (1)

- Solid–liquid two-phase continuity equation

Within the Eulerian–Eulerian framework, the compressibility effects of both solid and liquid phases were neglected in the simulation. The solid and liquid phases are modeled as interpenetrating continua, each satisfying an independent continuity equation [34]. Meanwhile, the convective term ∇⋅(αρv) in the continuity equation accurately characterizes the transport process of each phase. It captures the velocity-field-induced redistribution of phase volume fractions, which are subsequently substituted into the momentum equations [35,36]. Mass conservation is represented by the continuity equations, as shown in Equations (1) and (2):

- Liquid-phase continuity equation:

- Solid-phase continuity equation:where αl and αp are the volume fractions of the liquid and solid phases, ρl and ρp are their densities, and vl and vp are their velocity vectors.

- (2)

- Solid–liquid two-phase momentum conservation equation

Momentum variations in each phase in space are governed by the momentum conservation equations, as shown in Equations (3) and (4):

- Liquid-phase momentum equation:

- Solid-phase momentum equation:where p is the common fluid pressure, Pp the solid pressure (closed via KTGF), τl and τp the shear stress tensors of liquid and solid phases, g the gravitational acceleration vector, and Mlp the interphase momentum exchange force satisfying Mlp = −Mpl. Here, ω denotes the angular velocity vector of the rotating frame and r the position vector from the rotation center to the computational point, providing an accurate description of particle-fluid motion [37,38].

- (3)

- Equations for turbulent kinetic energy and dissipation rate

Within the Realizable k–ε model, the transport equations of turbulent kinetic energy k and dissipation rate ε are expressed in Equations (5) and (6):

- Equation for turbulent kinetic energy:where Pk denotes the turbulent kinetic energy production term, Gk the buoyancy-induced production, μ the molecular viscosity, μt the turbulent viscosity, σk the diffusion coefficient of turbulent kinetic energy, and ε the dissipation rate.

- Equation for turbulent dissipation rate:where σω denotes the diffusion coefficient of the turbulent dissipation rate, β1 and β2 are model constants, and ε/k is the production term of the dissipation rate, enabling accurate prediction in near-wall regions [39].

2.3. Numerical Methods

In this simulation, the SIMPLE scheme was applied for pressure–velocity coupling, and a second-order upwind discretization was used for variable interpolation at control volume surfaces. A time step of 0.0001 was adopted, with convergence achieved when residuals reached a total relative error below 0.0001, and the simulation was advanced for 2 s. Transient simulations were conducted using the Eulerian–Eulerian multiphase framework, with geometric models parameterized accordingly. Interphase momentum exchange was modeled with the Syamlal-O’Brien formulation [40,41], and turbulence was represented by the k–ε model [42]. In view of the fine size (mainly <0.5 mm, dominated by 0.045 mm particles) and low density (1.3–1.5 kg·cm−3) of coal particles in slurry water, they were modeled as spherical particles with diameters of 0.045–0.5 mm and a density of 1500 kg·cm−3. The particles are mainly subjected to traction, centrifugal, Coriolis and pressure gradient forces during the simulation process [43,44]. The maximum packing limit was set to 0.63, and the liquid phase was defined as water with a density of 998 kg·cm−3.

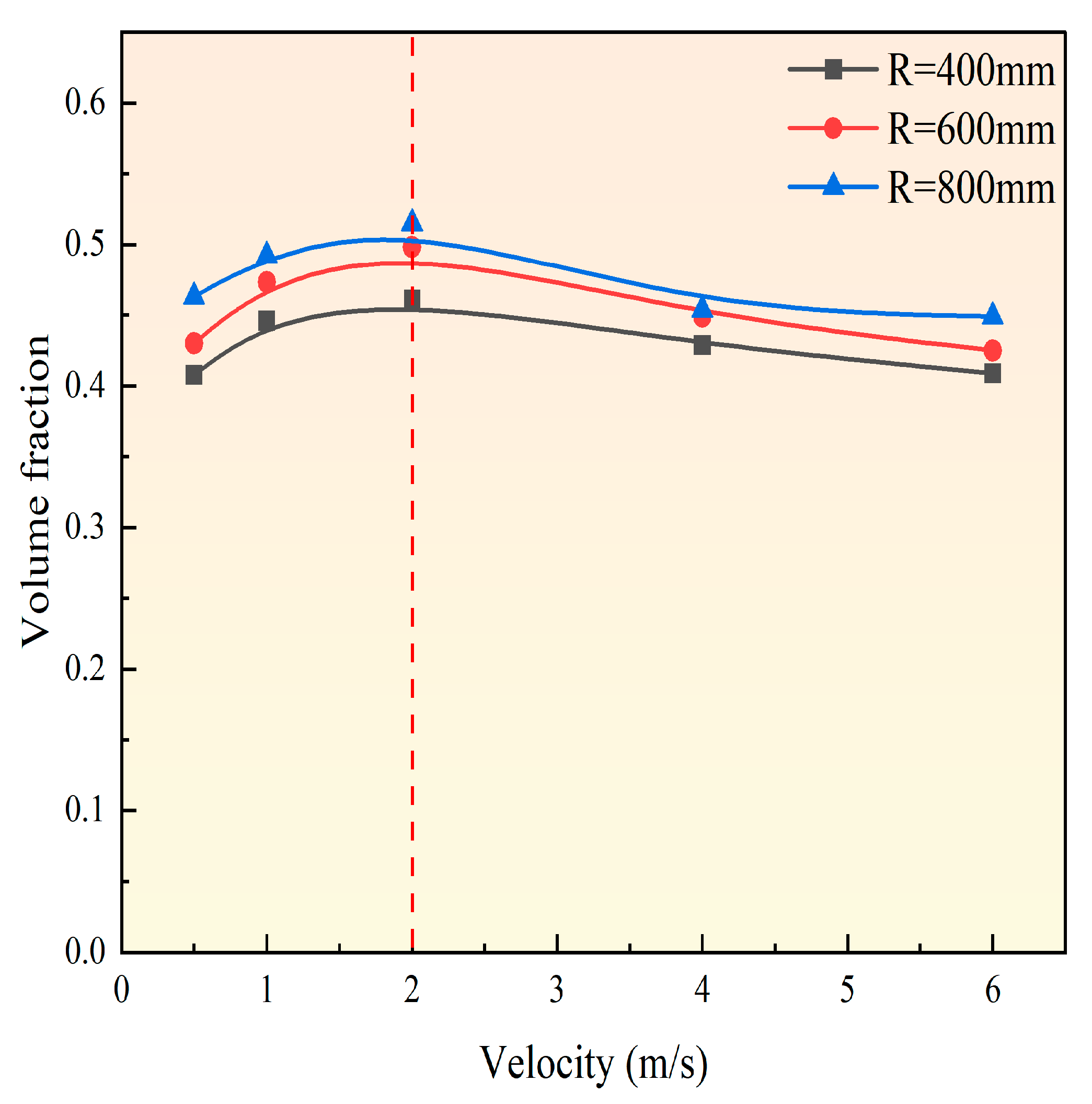

To investigate the influence of particle size, rotational speed, and centrifugal radius on coal particle deposition, a 3D model of the U-shaped high-gravity sedimentation-dewatering device was established, and corresponding numerical simulations were performed. Table 1 presents the boundary conditions: as shown in Figure 3, an inlet velocity of 2 m·s−1 yields the maximum particle volume fraction across all investigated centrifugal radii; accordingly, 2 m·s−1 was adopted as the initial boundary condition for subsequent simulations, the outlet was defined as a pressure outlet, and the walls were subjected to centrifugal rotation with a no-slip condition. Meanwhile, the interfacial slip was not included in the model [45].

Table 1.

Boundary conditions of the high-gravity sedimentation-dewatering device.

Figure 3.

Determination of inlet velocity.

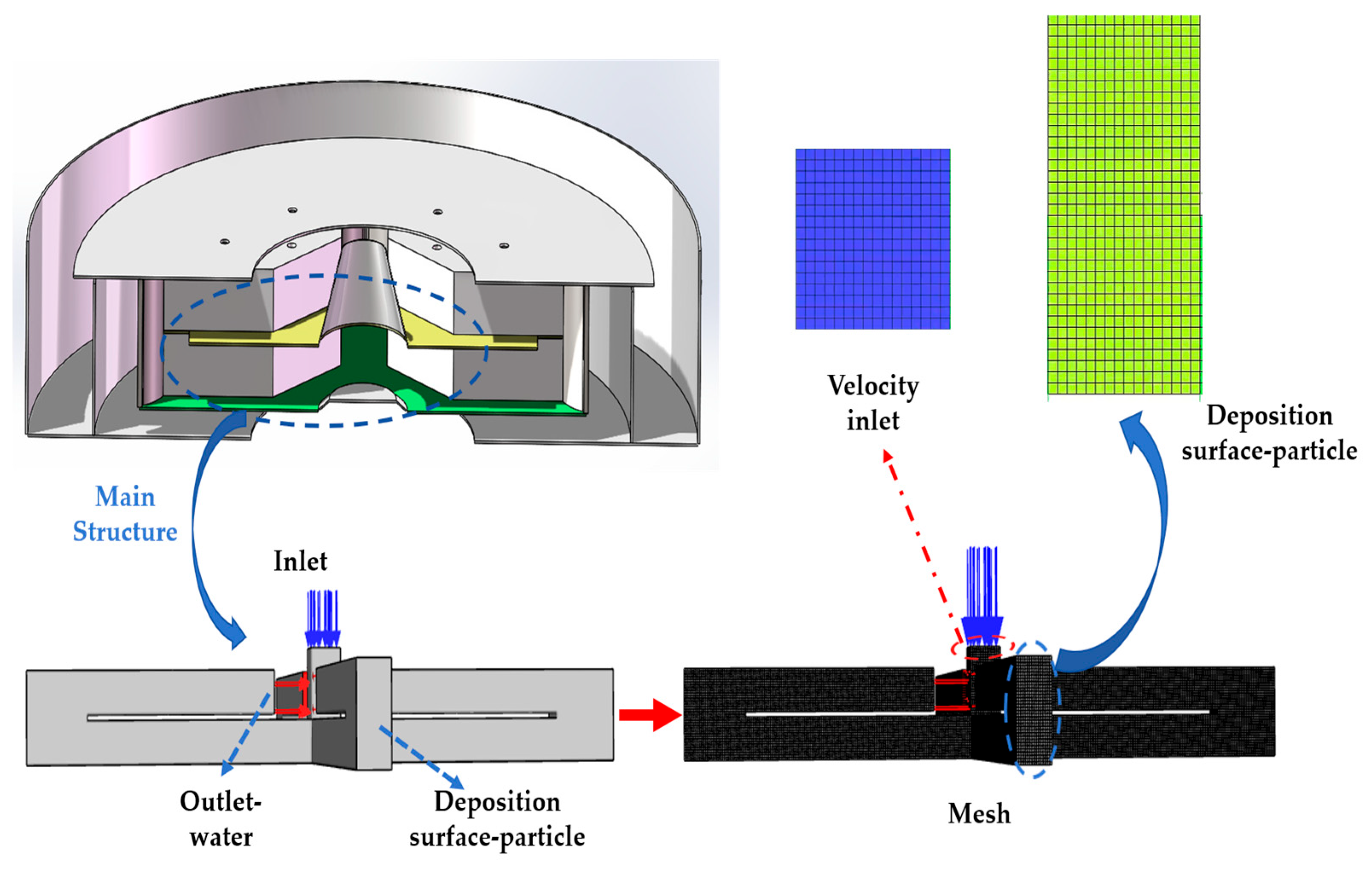

2.4. Mesh Generation and Independence Verification

The discretization of the computational domain into small control volumes is a crucial step in Fluent simulations, strongly affecting solution accuracy and computational efficiency. To ensure mesh quality and improve computational efficiency, a tetrahedral structured mesh was generated in ICEM-CFD, as illustrated in Figure 4 for the computational domain.

Figure 4.

Mesh generation of the main structure.

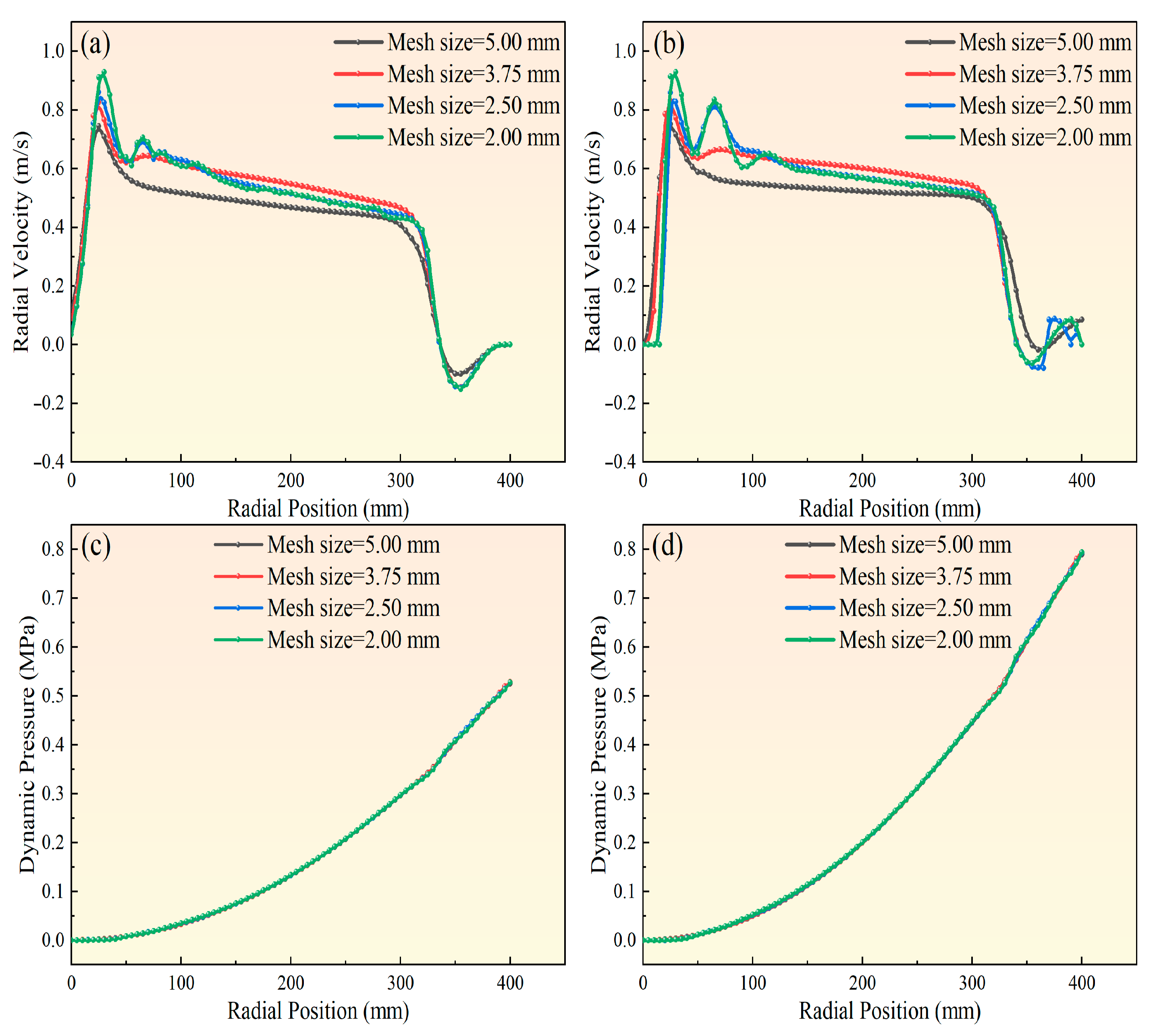

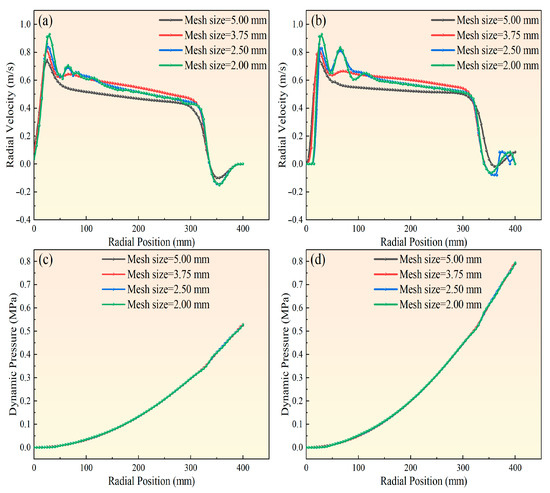

Mesh independence was assessed through transient simulations employing a pressure–velocity coupling solver. Mesh independence analysis was performed with water as the continuous phase and 0.045 mm coal particles as the dispersed phase, under centrifugal conditions of R = 400 mm and ω = 800 r·min−1. Four mesh densities were tested: 70,000 (5 mm), 150,000 (3.75 mm), 300,000 (2.5 mm), and 600,000 (2 mm) cells. As shown in Figure 5a,b present the radial velocity distributions of water and particles at different radial positions, while panels Figure 5c,d illustrate the dynamic pressure distributions of water and particles. The figure indicates that radial velocity distributions differed markedly at 70,000 and 150,000 cells, but became nearly unchanged at 300,000 and 600,000 cells. To enhance computational efficiency while ensuring accuracy, the mesh with approximately 300,000 cells (mesh size = 2.5 mm) was selected for the subsequent simulations.

Figure 5.

Verification of mesh independence:(a) radial velocity of water; (b) radial velocity of particles; (c) dynamic pressure of water; (d) dynamic pressure of particles.

3. Numerical Results and Discussion

3.1. Distribution of Solid-Phase Deposition

Deposition efficiency and dewatering degree serve as key performance indicators of high-gravity equipment, while in simulations, the particle volume fraction provides an indirect measure of material packing concentration [46,47]. Device performance was assessed based on particle volume fraction (0–0.63): higher values denote enhanced deposition and dewatering, whereas lower values indicate poor deposition and particle dispersion.

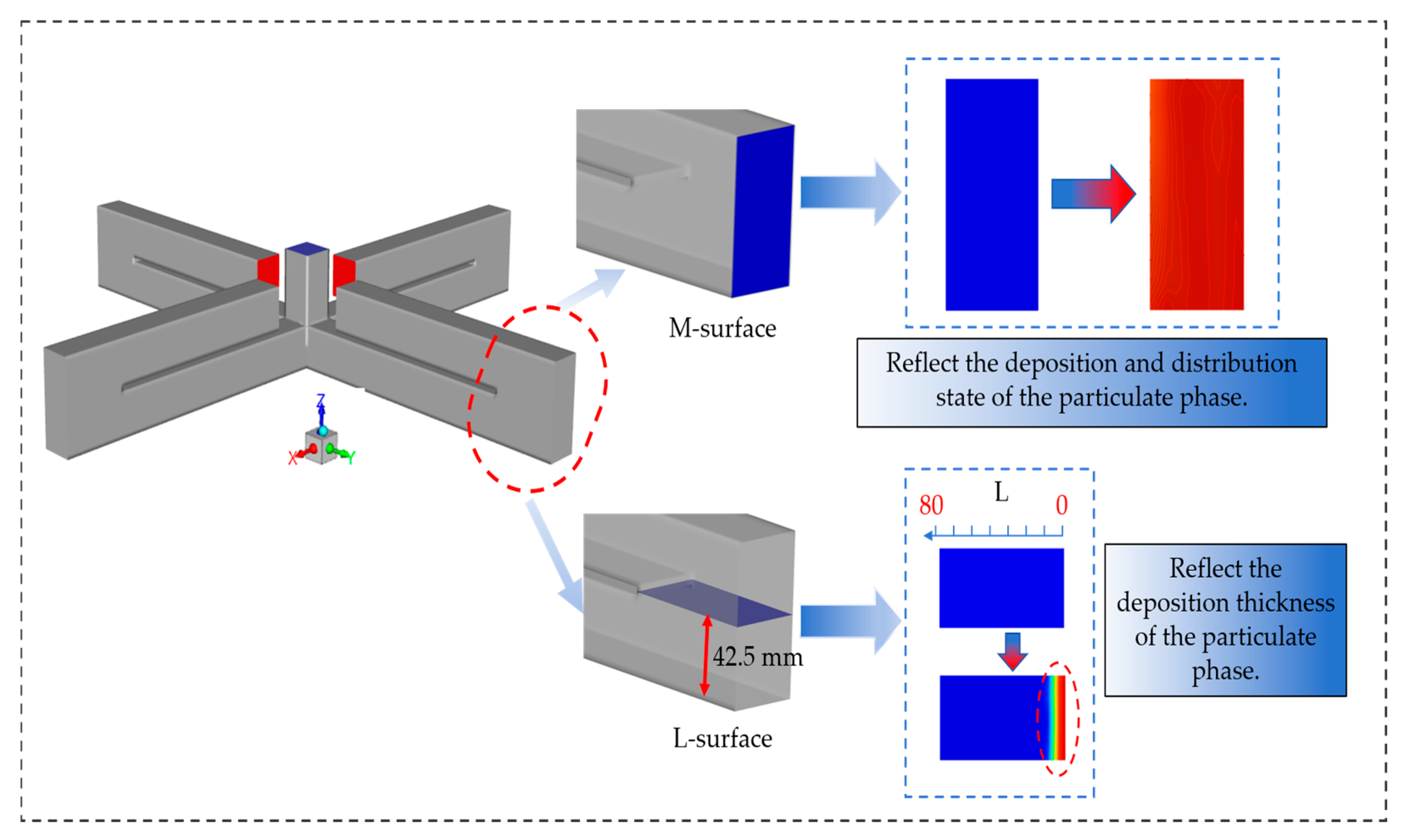

Figure 6 illustrates the selected sections: section M for particle deposition and section L at the horizontal plane of Z = 42.5 mm. In the section views, color denotes the particle volume fraction: blue (volume fraction = 0) corresponds to the absence of particle deposition, while the emergence of other colors (such as cyan and orange) indicates the initiation of particle accumulation on the deposition surface. Meanwhile, the transition to deeper colors, reaching red, indicates a higher degree of particle accumulation, stronger compactness, and enhanced dewatering performance, leading to the formation of an effective deposition thickness.

Figure 6.

Selection of cross-sections at different positions.

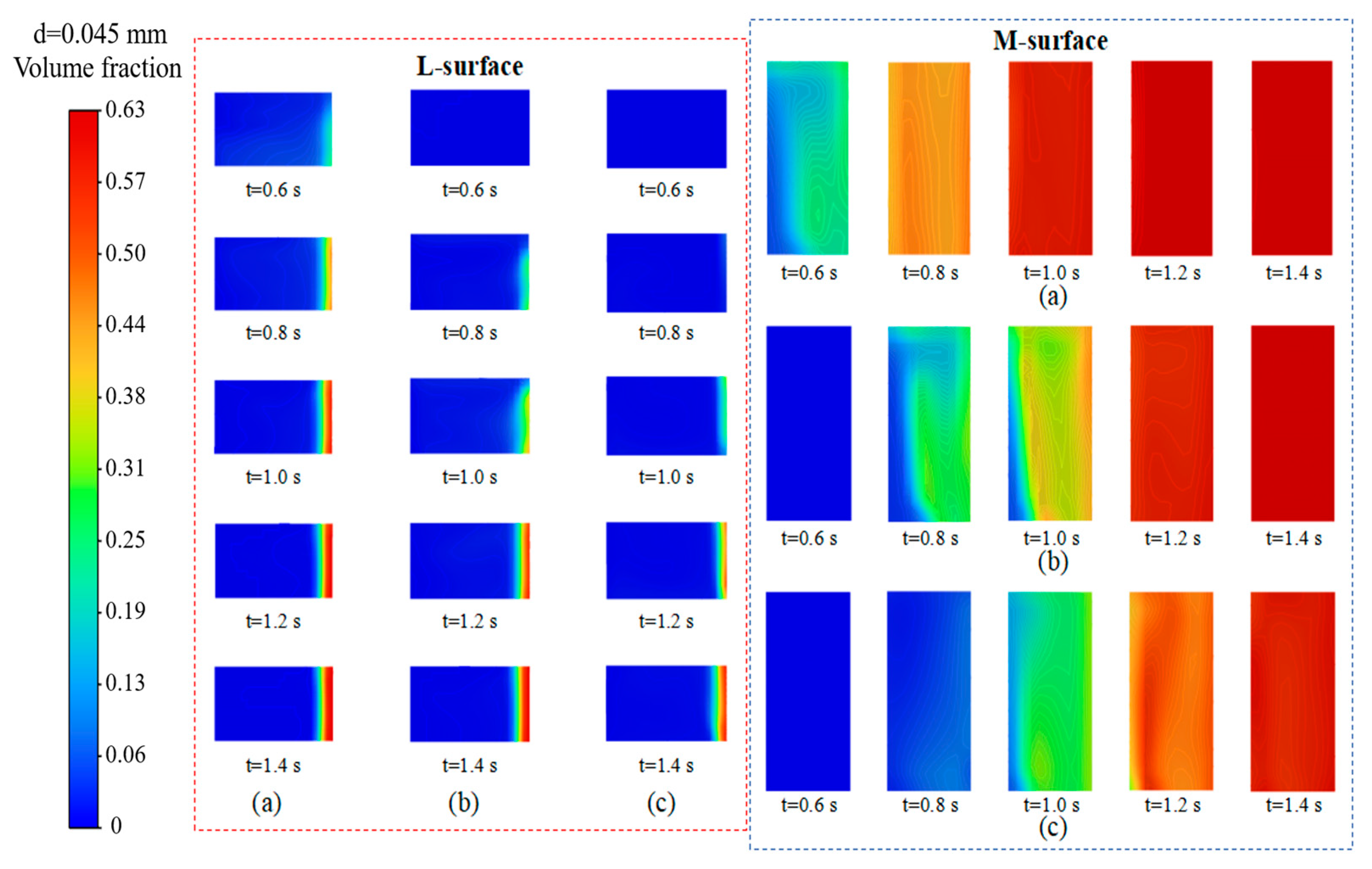

As shown in Figure 7, the deposition distributions of particles with a diameter of d = 0.045 mm are presented at different sections under varying rotational speeds and centrifugal radii, where the color gradient from blue to red reflects an increase in volume fraction. Figure 8 illustrates the corresponding particle volume fraction distributions. Figure 7 and Figure 8 demonstrate that, at a constant rotational speed, increasing the centrifugal radius improves particle uniformity and deposition in the high-volume-fraction (red) region. At 400 r·min−1, only a diffuse cyan region appears at the right margin when R = 400 mm, whereas at R = 800 mm a compact orange-red high-volume-fraction zone is formed, indicating that larger radii markedly enhance particle deposition by strengthening centrifugal force and suppressing diffusive disturbances. At R = 400 mm, the extent of the high-volume-fraction (red) region increases with rising rotational speed. At 400 r·min−1, particles exhibit a non-uniform distribution (volume fraction = 0.31), while at 1200 r·min−1 they reach the packing limit (volume fraction = 0.63), forming a 5 mm deposition layer. This demonstrates that increasing rotational speed facilitates particle migration and enrichment, thereby strengthening their capacity to overcome flow resistance. Comparative analysis reveals that at high rotational speed (1200 r·min−1) and large centrifugal radius (600–800 mm), fine coal particles can be efficiently processed, resulting in the formation of a pronounced deposition layer.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of particles under different rotational speeds and centrifugal radii: (a) ω = 400 r·min−1; (b) ω = 800 r·min−1; (c) ω = 1200 r·min−1.

Figure 8.

Particle volume fraction under different rotational speeds and centrifugal radii: (a) 400 r·min−1; (b) 800 r·min−1; (c) 1200 r·min−1.

As shown in Figure 9, the deposition thickness and distribution of coal particles with a diameter of d = 0.045 mm are presented at different centrifugal radii under a constant rotational speed, as a function of time. At a constant radius, increasing the simulation time from 0.6 s to 1.4 s shifts particle deposition from edge-localized enrichment (cyan-green, low concentration) to extensive cross-sectional coverage (orange-red, high concentration). At R = 400 mm, the particle volume fraction increases from 0.15 to 0.63 over time, demonstrating that temporal evolution is critical for particle migration and enrichment, as sustained centrifugal force drives continuous accumulation and a progressive rise in volume fraction. At t = 1.2 s, particles within the small-radius (400 mm) flow field complete migration within t ≤ 1.2 s, resulting in the rapid formation of a 2 mm effective deposition layer. Under the large-radius condition (800 mm), the increased radial migration distance of particles hinders their deposition within a short period of time. With extended time (t > 1.2 s), larger centrifugal radii accelerate the approach to the packing limit (0.63). At R = 400 mm the increase is gradual, while at R = 800 mm it is steep, yielding a rapid low-to-high volume fraction transition and a denser deposition layer.

Figure 9.

Spatial distribution of particles at different sections under varying centrifugal radii and times: (a) R = 400 mm; (b) R = 600 mm; (c) R = 800 mm.

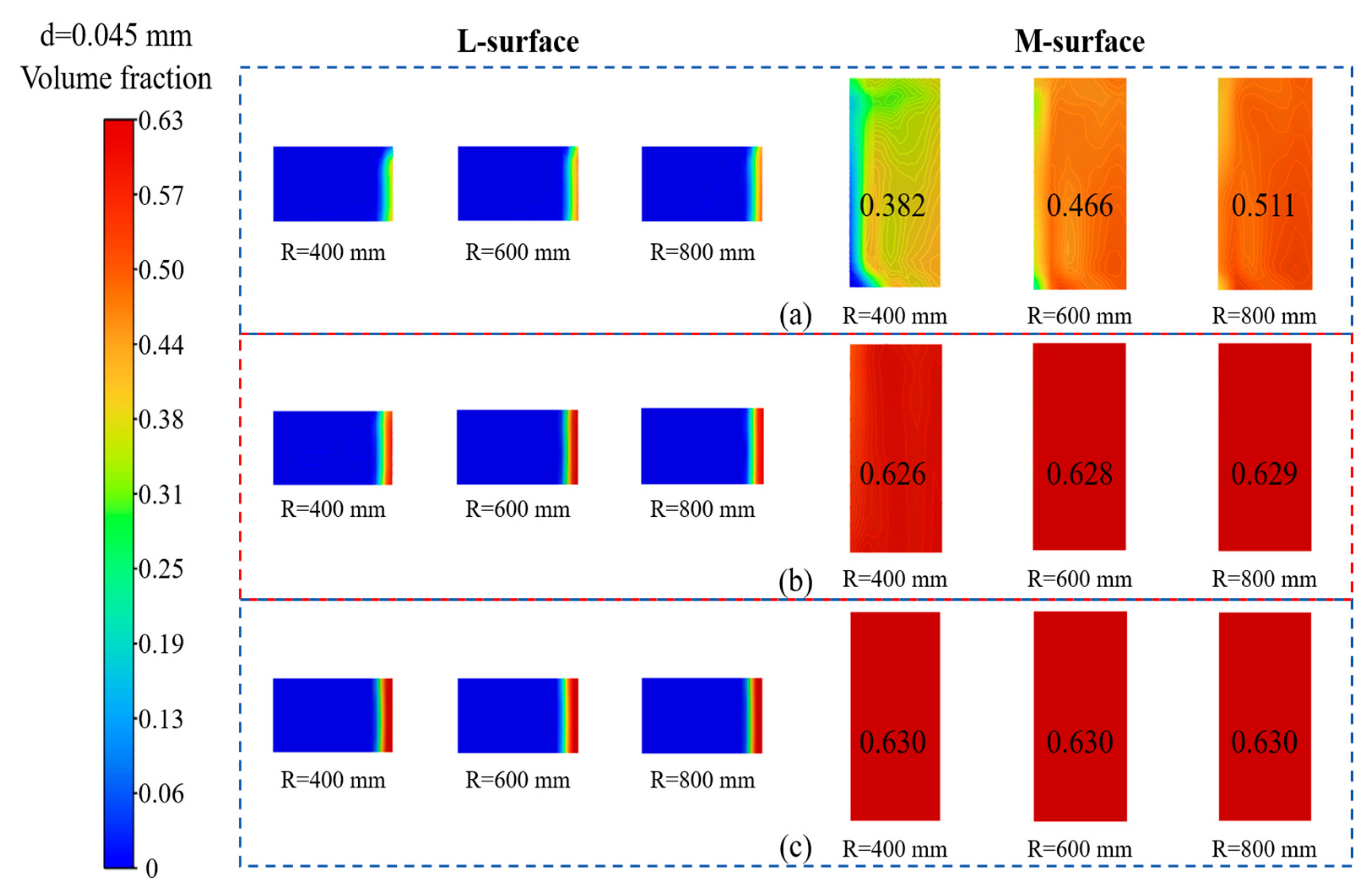

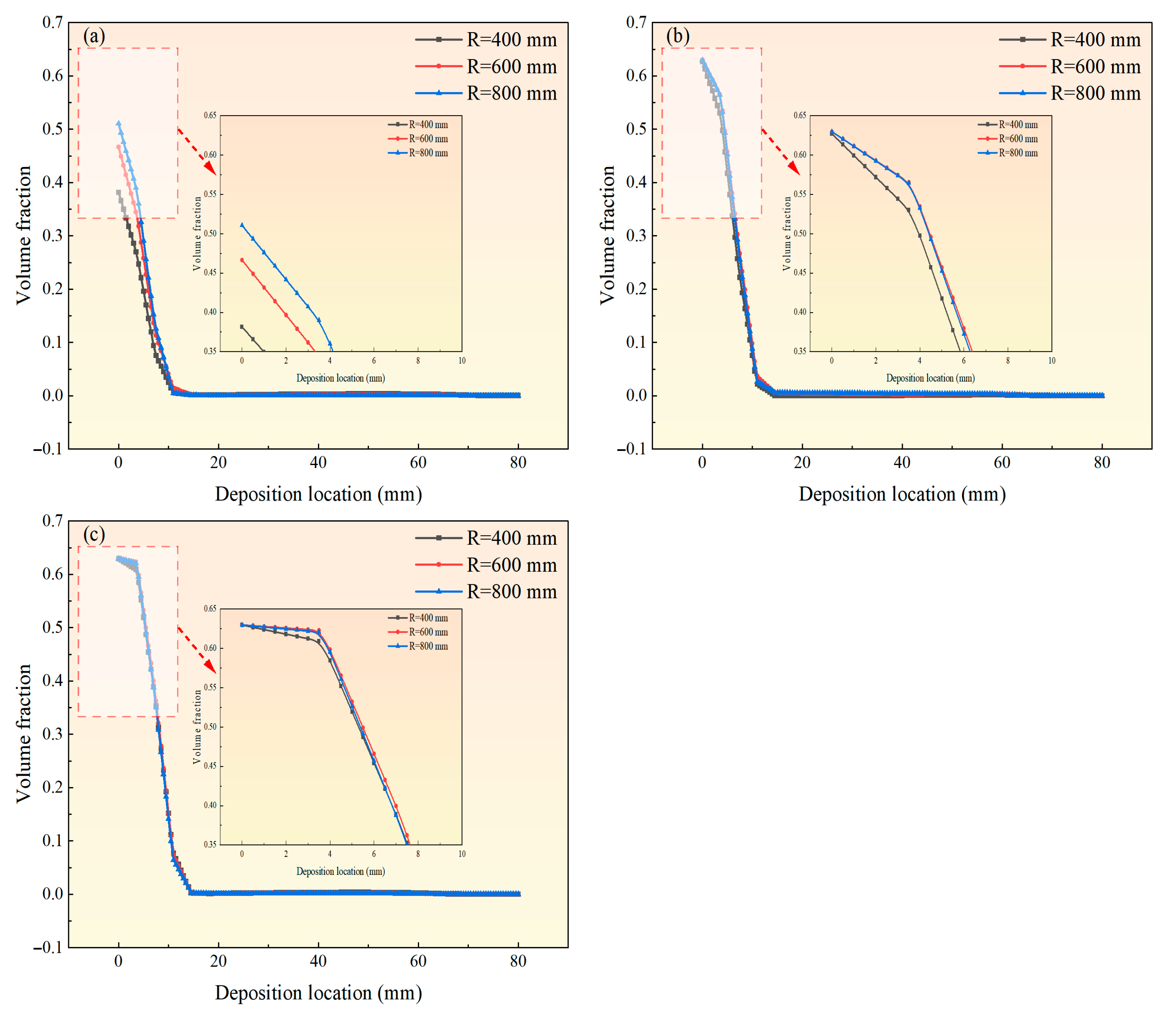

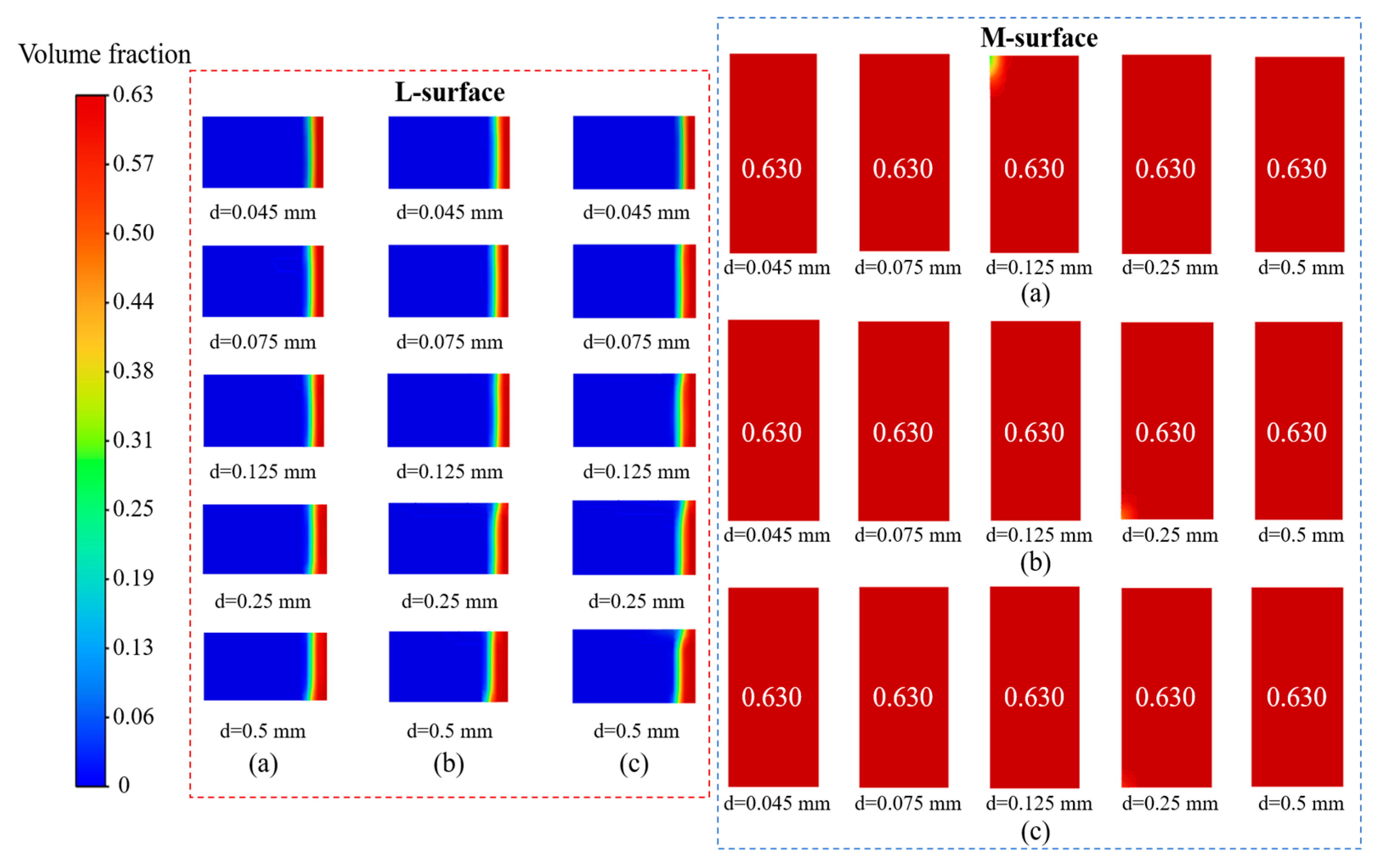

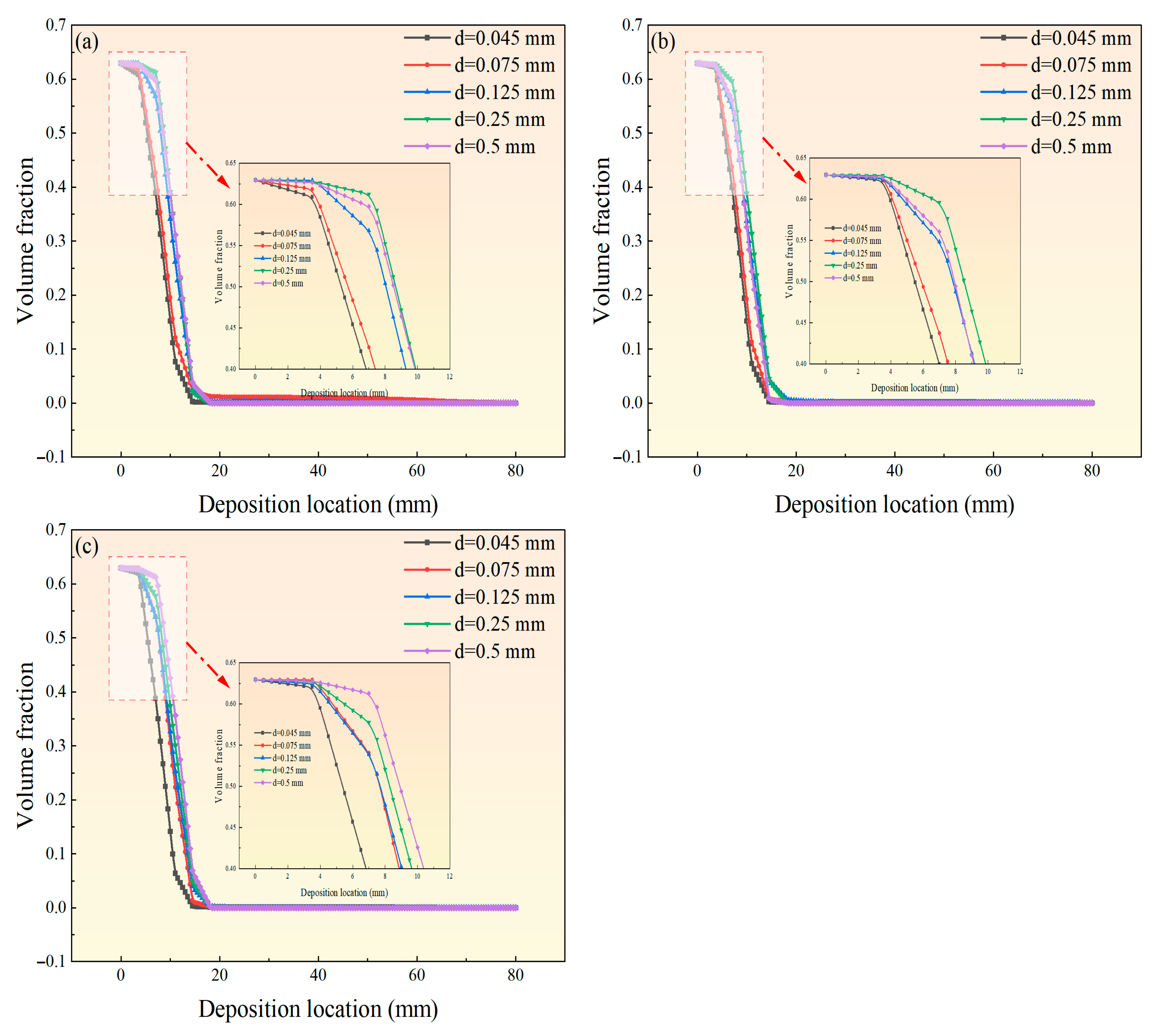

Figure 10 and Figure 11 present the spatial distribution and volume fraction of particles of different sizes under various centrifugal radii at 1200 r·min−1. Under high rotational speed (1200 r·min−1), the synergistic effects of centrifugal radius and particle size on deposition behavior (particle distribution and thickness) were examined. The results reveal that particle size is the dominant factor, while centrifugal radius also exerts significant control over the deposition process by modulating the intensity of the centrifugal force. The results indicate that at 1200 r·min−1, particles of different sizes and centrifugal radii on the deposition surface attain the packing limit volume fraction of 0.63. When the radius increases from 400 to 800 mm, deposition thickness rises with volume fractions ≥0.5, indicating that larger radii offset the settling limitations of fine particles and that the deposition of small particles (0.045 mm) is governed by centrifugal radius. For medium-sized particles (0.075 and 0.125 mm), a larger centrifugal radius increases deposition thickness and compactness, enlarges the high-volume-fraction region with clearer boundaries, and promotes migration and enrichment through enhanced centrifugal force. Large particles (0.25 and 0.5 mm) form dense deposits at all radii, but larger radii yield steeper profiles with sharper edges and high-concentration zones concentrated outward, indicating that stronger centrifugal forces impart greater kinetic energy and result in more compact accumulation.

Figure 10.

Spatial distribution of particles of different sizes at varying radii: (a) R = 400 mm; (b) R = 600 mm; (c) R = 800 mm.

Figure 11.

Particle volume fraction of different sizes at varying radii: (a) R = 400 mm; (b) R = 600 mm; (c) R = 800 mm.

3.2. Analysis of Flow Field Characteristics

Analysis of particle volume-fraction contours and associated data reveals pronounced differences in coal particle deposition under varying rotational speeds, centrifugal radii, and particle sizes. Meanwhile, to elucidate the variation in particle deposition characteristics, the internal flow field behavior of the high-gravity sedimentation-dewatering device was investigated through numerical simulation. A systematic analysis of the dynamic pressure and radial velocity of water and particles was performed under varying centrifugal conditions (rotational speed, radius, and particle size), with reference to changes in particle volume fraction and deposition behavior.

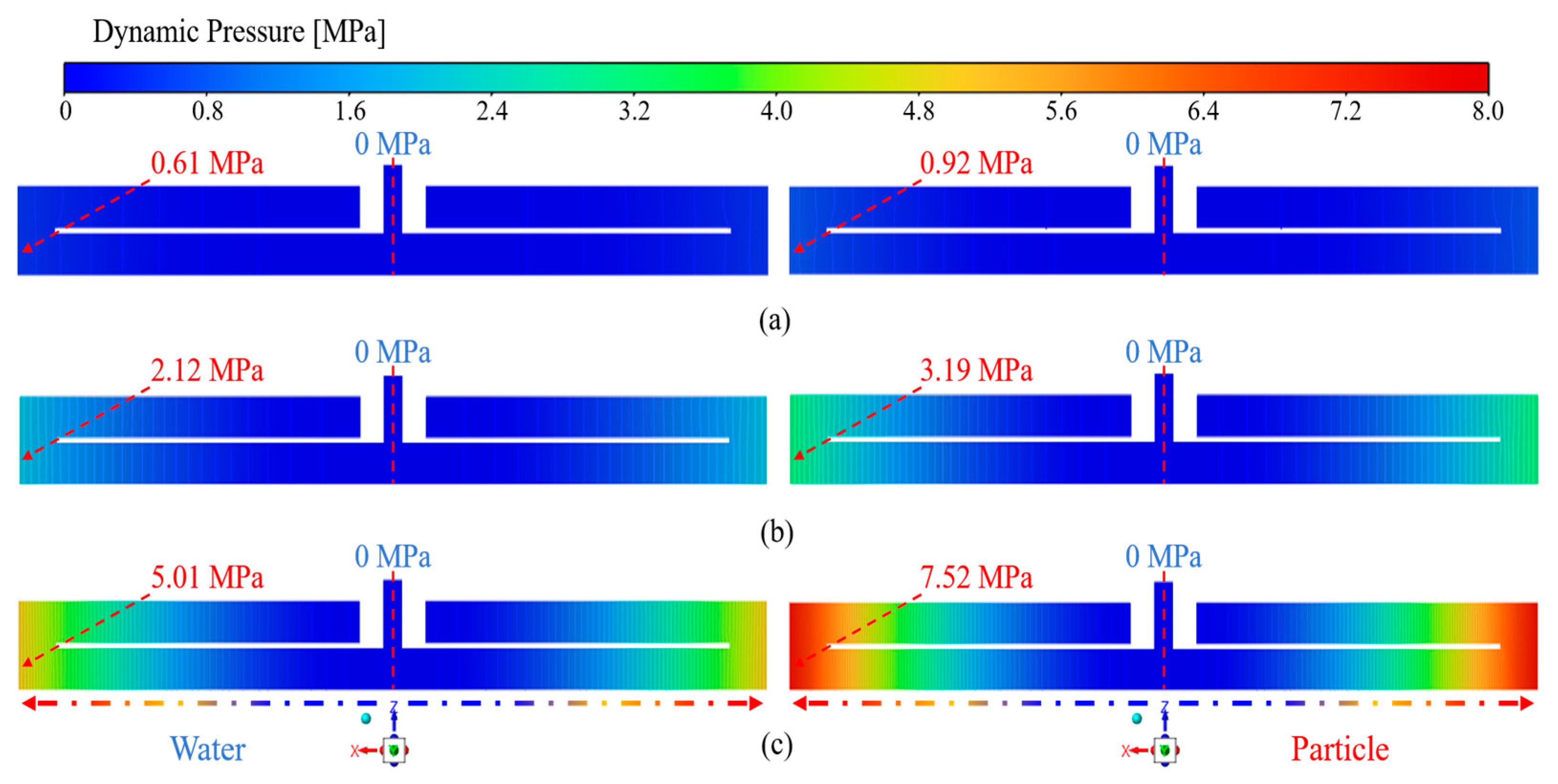

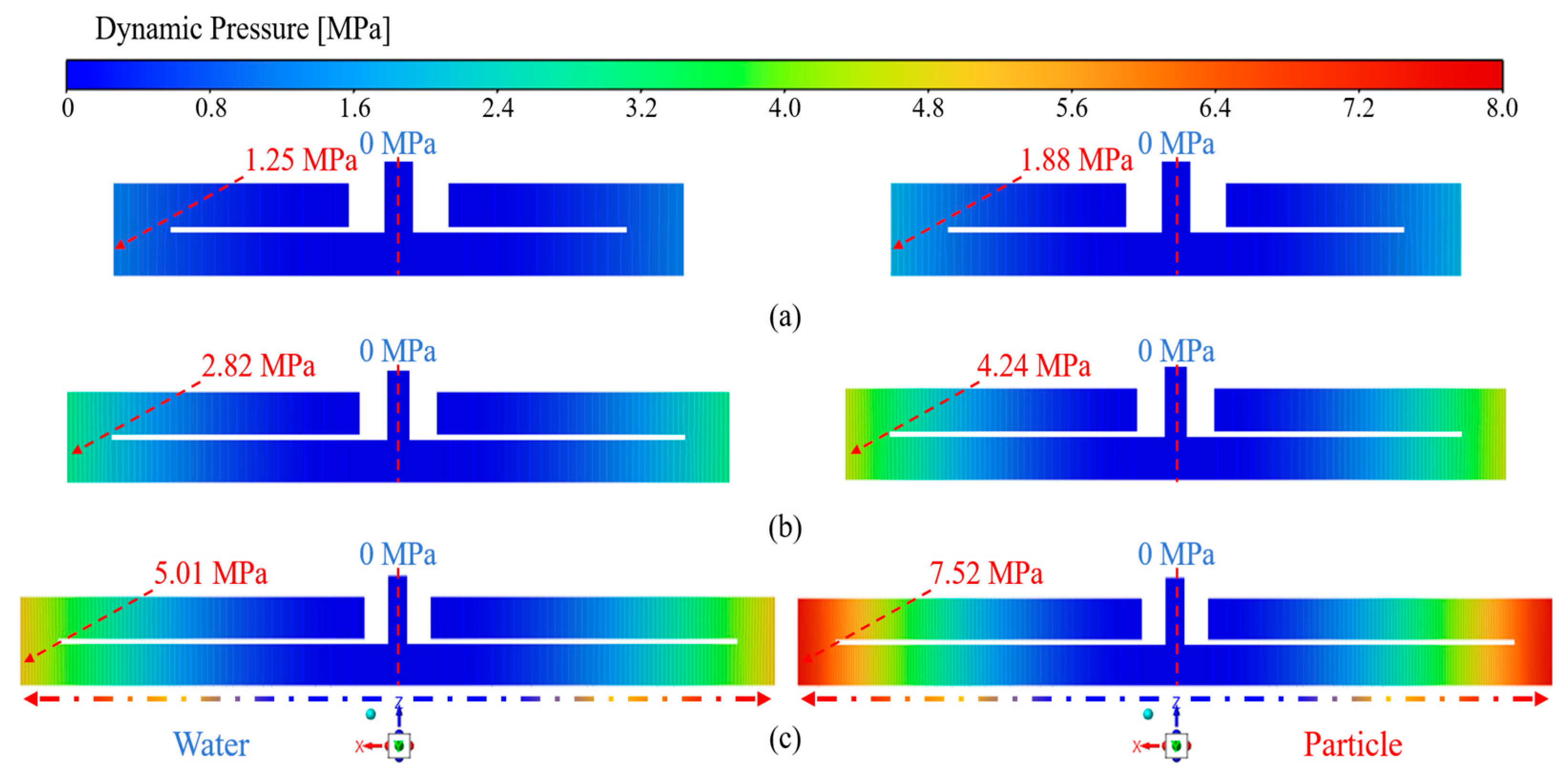

3.2.1. Pressure Distribution

As shown in Figure 12, the spatial distribution of dynamic pressure for the fluid and particle phases is presented at a centrifugal radius of 800 mm with a particle size of 0.045 mm under different rotational speeds. The results indicate that increasing rotational speed elevates boundary pressure and alters the pressure gradient, with fluid dynamic pressure rising from 0.61 to 5.01 MPa and particle dynamic pressure from 0.92 to 7.52 MPa, the latter remaining consistently higher than that of the fluid. As the rotational speed increases from 400 to 1200 r·min−1, the particle–fluid dynamic pressure difference grows from 0.31 to 2.51 MPa. The larger the difference, the greater the particle accumulation on the wall, consistent with Figure 7a–c, which shows thicker deposition layers at higher speeds for a given radius. These results demonstrate that higher rotational speeds intensify particle interactions, while radial pressure variations facilitate rapid particle transport and compact deposition on the wall, leading to sediment layer formation.

Figure 12.

Effect of rotational speed on the spatial distribution of dynamic pressure: (a) ω = 400 r·min−1; (b) ω = 800 r·min−1; (c) ω = 1200 r·min−1.

As shown in Figure 13, the spatial distribution of dynamic pressure for the fluid and particle phases is illustrated at a fixed rotational speed of 1200 r·min−1 with a particle size of 0.045 mm under different centrifugal radii (400–800 mm). The study reveals that increasing the centrifugal radius from 400 to 800 mm markedly elevates the dynamic pressures of both fluid and particles. At R = 400 mm, the fluid pressure is uniformly distributed with a mild gradient, the particle–fluid dynamic pressure difference is 0.63 MPa, and no distinct high-pressure region is formed, reflecting a weak centrifugal effect. At R = 800 mm, the particle–fluid dynamic pressure difference increases to 2.51 MPa and a concentrated high-pressure zone emerges, demonstrating that centrifugal radius critically regulates multiphase pressure behavior in high-speed centrifugation, with pressure gradients strongly influencing particle deposition efficiency. Thus, at a constant rotational speed, increasing the centrifugal radius enhances particle deposition by facilitating migration and settling, while also revealing more complex deposition mechanisms under large-radius conditions, consistent with the deposition behavior shown in Figure 7a.

Figure 13.

Effect of centrifugal radius on the spatial distribution of dynamic pressure: (a) R = 400 mm; (b) R = 600 mm; (c) R = 800 mm.

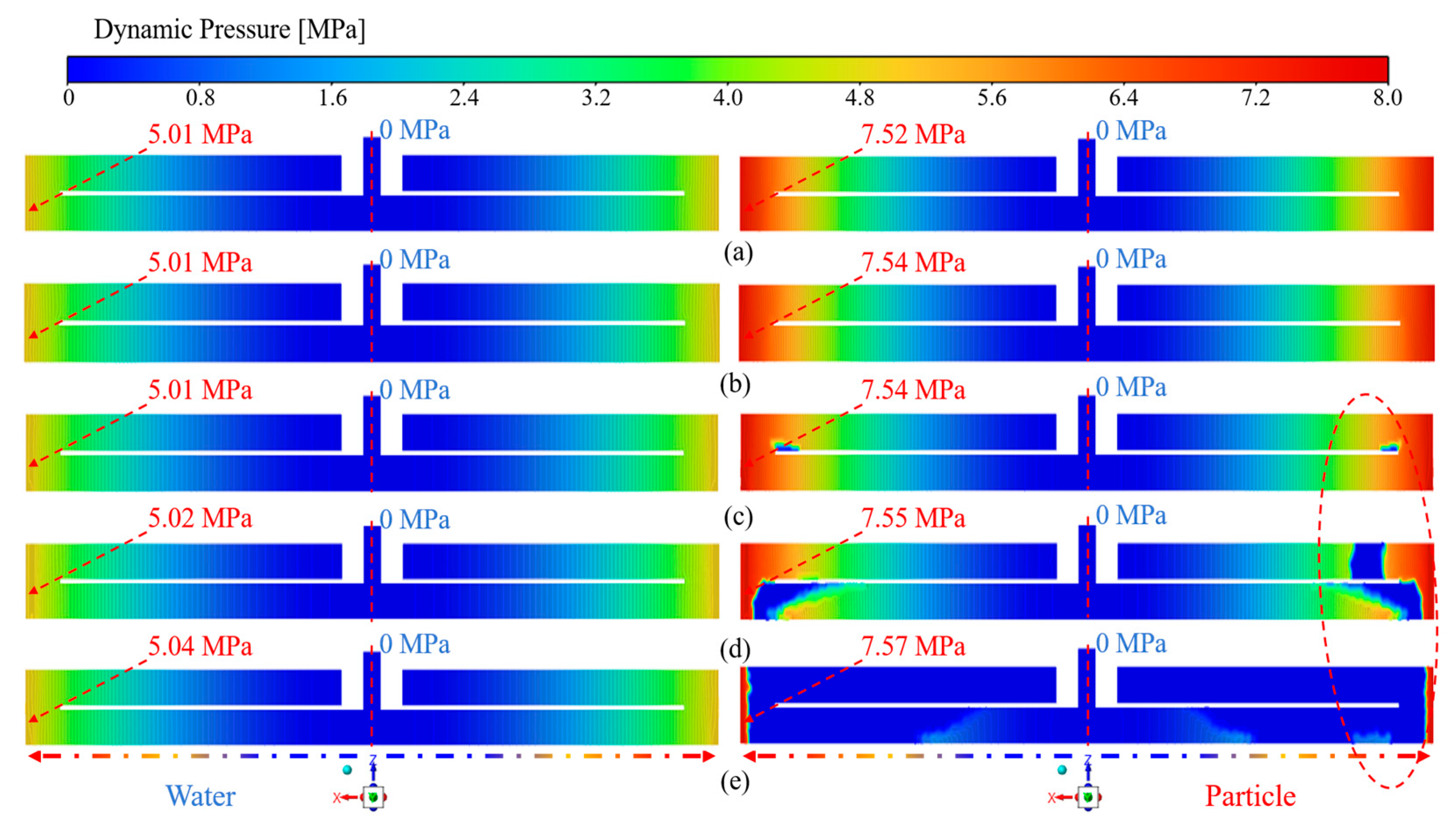

From the pressure distributions in Figure 12 and Figure 13, it can be concluded that at R = 800 mm and 1200 r·min−1, 0.045 mm particles achieve the most effective deposition. Accordingly, at R = 800 mm and 1200 r·min−1, the effects of particle size on the dynamic pressure distributions of fluid and particle phases were examined, as shown in Figure 14. Results show that increasing particle size elevates the overall dynamic pressure of the flow field and markedly alters particle distribution behavior. Fluid dynamic pressure exhibits a continuous distribution, while particle pressure increases from 7.52 to 7.57 MPa with particle size, suggesting enhanced deposition propensity. For d ≥ 0.125 mm, particle distribution becomes non-uniform and spatial heterogeneity is significant. Larger particle sizes exacerbate the non-uniform pressure distribution in the flow field, significantly affecting local particle-phase pressure, and Figure 10c confirms the trend that greater particle size enhances deposition efficiency.

Figure 14.

Effect of particle size on the spatial distribution of dynamic pressure: (a) d = 0.045 mm; (b) d = 0.075 mm; (c) d = 0.125 mm; (d) d = 0.25 mm; (e) d = 0.5 mm.

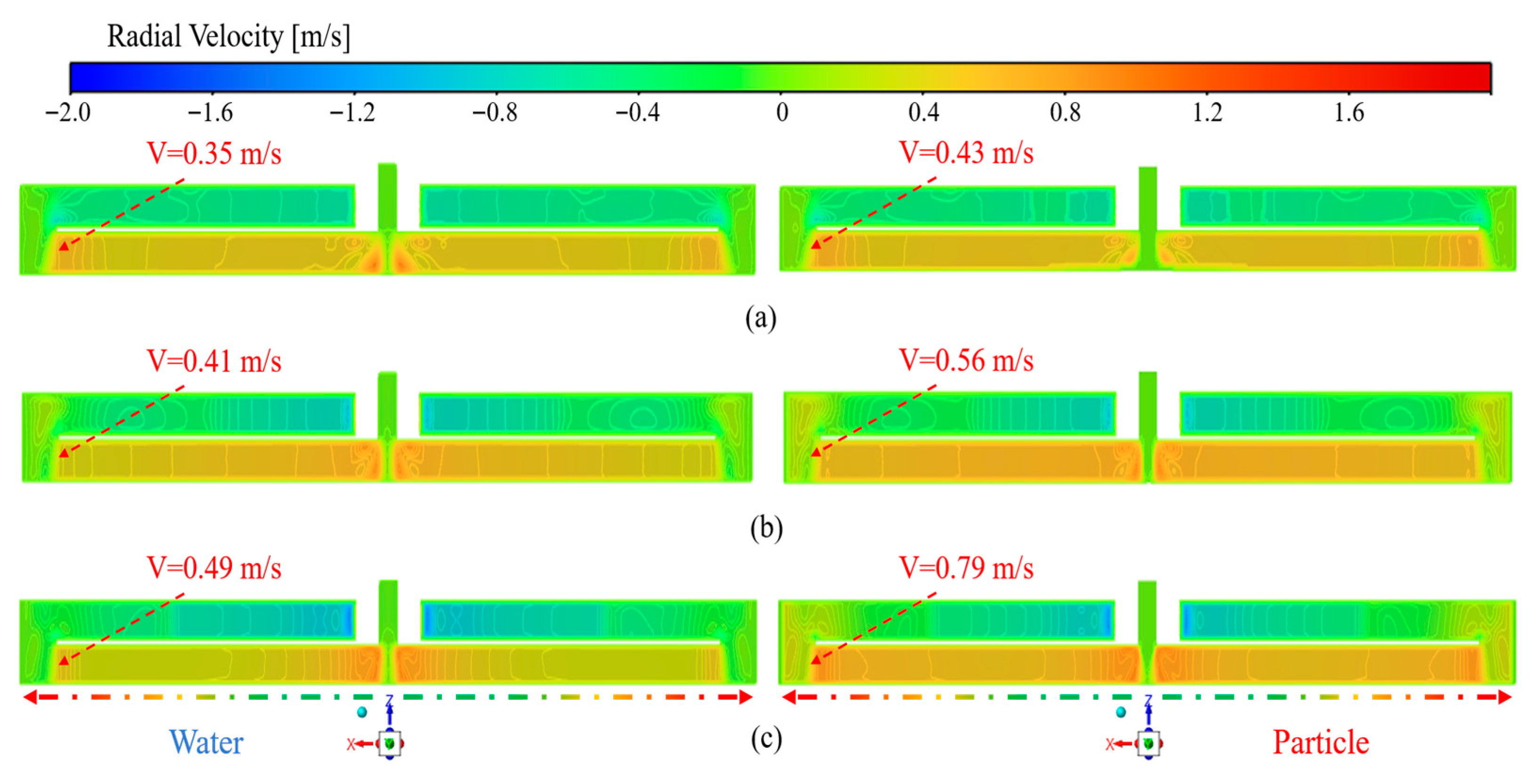

3.2.2. Velocity Distribution

As shown in Figure 15, the spatial distribution of radial velocity for the fluid and particle phases at different rotational speeds is presented for a centrifugal radius of 800 mm and a particle size of 0.045 mm. The blue-to-red color gradient denotes the shift in radial velocity from −2 to 2 m·s−1, visually illustrating the radial motion of the fluid (water) and particle phases. Velocity distribution curves indicate that at 1200 r·min−1, the mean radial velocity of the fluid decreases compared with 400–800 r·min−1, while the particle-phase velocity increases. With increasing rotational speed, the velocity difference between particles and water becomes more pronounced, inducing interphase slip that facilitates the rapid migration and deposition of fine particles (0.045 mm) within the flow field. Results indicate that higher rotational speeds complicate the internal flow field, increase flow instability, steepen radial velocity gradients, and enhance outward flow, collectively improving the deposition efficiency of fine coal particles (0.045 mm).

Figure 15.

Effect of rotational speed on the spatial distribution of radial velocity: (a) ω = 400 r·min−1; (b) ω = 800 r·min−1; (c) ω = 1200 r·min−1.

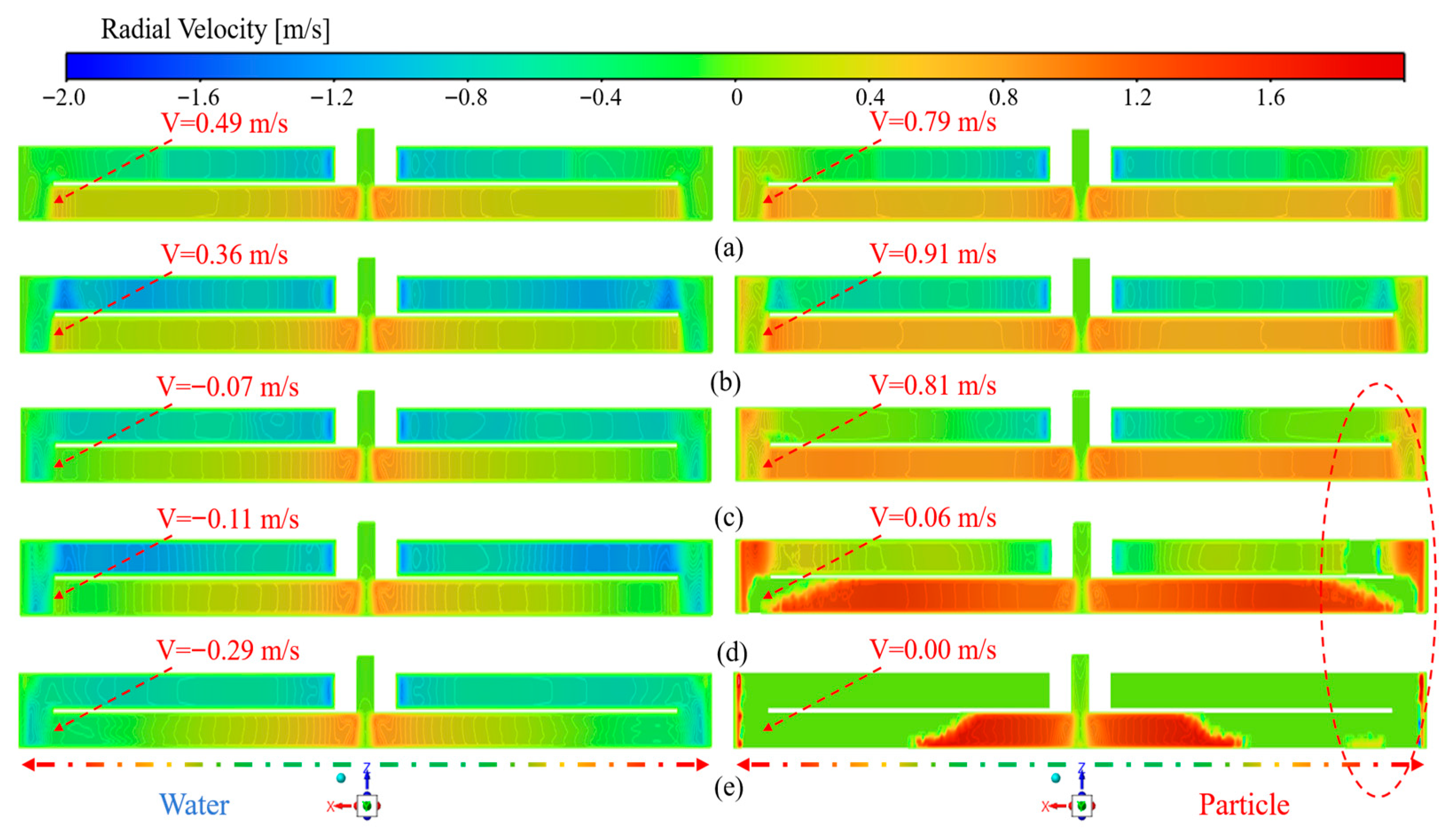

As shown in Figure 16, the spatial distribution of radial velocity for water and particles at a fixed rotational speed of 1200 r·min−1 with a particle size of 0.045 mm is presented, analyzing the influence of different centrifugal radii (400–800 mm) on the radial flow characteristics of the fluid and particle phases. Results show that increasing centrifugal radius reduces the radial velocity of water from 0.52 to 0.49 m·s−1, while raising that of particles from 0.67 to 0.79 m·s−1, thereby enlarging the interphase velocity difference. The particles exhibit a non-uniform and discrete velocity distribution, which intensifies the interphase slip effect, resulting in more distinct flow field partitioning, enhanced flow kinetic energy, and pronounced velocity gradients. Meanwhile, the velocity variation on the outer side remains relatively smooth, reflecting the differences in particle inertia and interphase interaction mechanisms. It is observed that at a centrifugal radius of 800 mm, the interphase slip motion between particles and water becomes most pronounced, enabling fine particles to rapidly accomplish solid–liquid separation within the flow field and to form a distinct, compact, and effective sediment layer.

Figure 16.

Effect of centrifugal radius on the spatial distribution of radial velocity: (a) R = 400 mm; (b) R = 600 mm; (c) R = 800 mm.

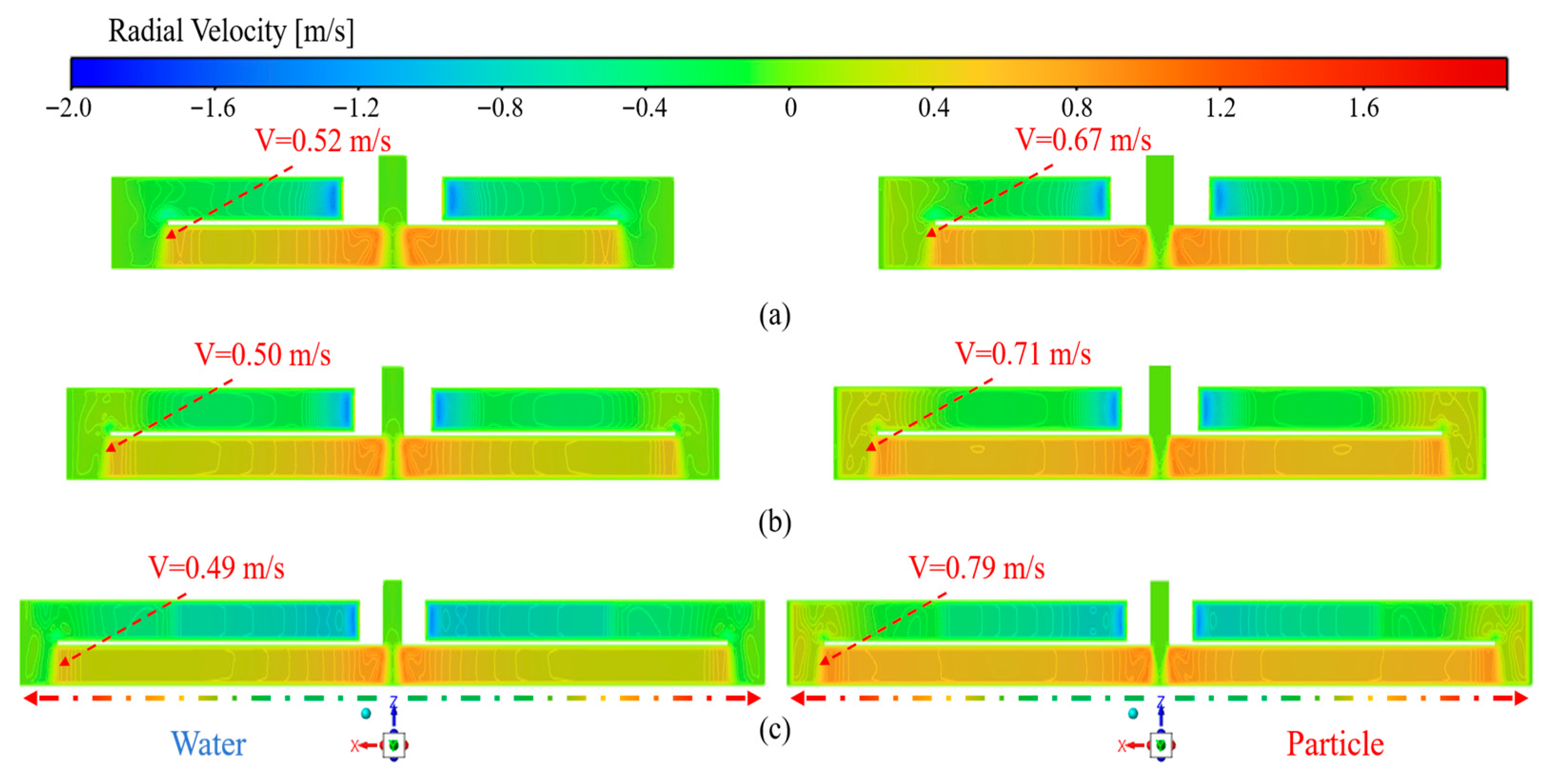

Under fixed centrifugal conditions (rotational speed of 1200 r·min−1 and radius of 800 mm), the influence of particle size (0.045–0.5 mm) on the radial flow characteristics of both the water and particle phases was analyzed. As shown in Figure 17, the spatial distributions of radial velocity for the water and particle phases in the flow field are presented for different particle sizes. The results indicate that with increasing particle size, the radial velocity of the water phase gradually decreases, whereas that of the particle phase increases, leading to an enlarged radial velocity difference between the two phases. When the particle size is ≥0.25 mm, particles rapidly deposit along the wall surface. At a particle size of d = 0.5 mm, no particles remain at the bend region, resulting in V = 0 m·s−1, while a small fraction persists in a dispersed state within the flow field, leading to a discretized velocity distribution accompanied by pronounced local vortices and velocity stratification. For particles with sizes < 0.125 mm, the inertial effect is markedly enhanced under high rotational speed and large radial conditions, where the coupling of centrifugal and inertial forces facilitates their radial migration and subsequent deposition.

Figure 17.

Effect of particle size on the spatial distribution of radial velocity: (a) d = 0.045 mm; (b) d = 0.075 mm; (c) d = 0.125 mm; (d) d = 0.25 mm; (e) d = 0.5 mm.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically elucidates the intrinsic mechanisms governing particle settling behavior in the super-gravity dewatering process, highlighting the synergistic effects of rotational speed, centrifugal radius, and particle size. The findings demonstrate that increasing the rotational speed and centrifugal radius strengthens the centrifugal field, thereby significantly enhancing the migration and deposition of fine coal particles. Rather than relying on chemical flocculants or thickeners, the process enhances dynamic pressure gradients and interphase slip velocity to effectively overcome fluid resistance, facilitating particle transport toward the wall and the formation of a dense sediment layer. Meanwhile, increasing particle size enhances inertial effects and accelerates settling, whereas under high rotational speed and large centrifugal radius, the settling performance of fine particles (d = 0.045 mm) is effectively compensated and optimized.

Through an in-depth analysis of the flow field characteristics, it was found that when R = 800 mm, the particle volume fraction of 0.045 mm particles reached the packing limit and remained stable within 1.4 s at a rotational speed of 1200 r·min−1. In contrast, at 400 r·min−1, the packing limit was not reached within 2 s, and the particle volume fraction continued to vary with time. Meanwhile, the dynamic pressure of the particle phase remained consistently higher than that of the fluid phase. The resulting dynamic pressure difference served as a key driving factor for particle migration. The increased radial velocity difference between particles and fluid enhanced the interphase slip effect, thereby improving the efficiency of solid–liquid separation. This indicates that under high operating parameters, the flow field exhibits a more pronounced velocity gradient and kinetic energy, ensuring the rapid migration and stable deposition of fine particles.

In summary, the synergistic effects of rotational speed, centrifugal radius, and particle size generate high dynamic pressure differentials and pronounced interphase slip velocities within the flow field, which together constitute the key driving forces for enhancing the radial migration and dense deposition of fine particles. Compared with conventional centrifugal sedimentation equipment, this study demonstrates that precise parameter control can be tailored to different coal particle sizes, enabling fine particles to settle rapidly without reliance on chemical additives. While maintaining high processing efficiency, the approach markedly enhances the capture and enrichment of fine particles, exhibiting superior solid–liquid separation performance and process optimization potential, thereby providing a solid theoretical foundation for the precise design and optimization of centrifugal separation processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.; methodology, H.P.; software, H.P.; data curation, H.P.; writing—original draft preparation, H.P.; writing—review and editing, L.L., W.G. and C.K.; supervision, L.L., W.G. and C.K.; project administration, L.L. and C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 52174232]; the Project was supported by Anhui University of Science and Technology 2025 graduate student innovation fund [grant number 2025cx1011].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ding, S.; Pan, F.; Zhou, S.; Bu, X.; Alheshibri, M. Ultrasonic-assisted flocculation and sedimentation of coal slime water using the Taguchi method. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 10523–10536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kong, C.; Zhao, H.; Lu, F. Elucidating the enhancement of kaolinite flotation by iron content through density functional theory: A study on sodium oleate adsorption efficiency. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 34, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Guo, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, B. Influence of coal slime on migration behavior and ecological risk of heavy metals during hydrothermal carbonation of sewage sludge. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 13, 115031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Z. Interfacial mechanism of enhanced coal slime flotation using microemulsion collectors. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Park, H.; Wang, L. A Model–Based Parametric Study of Centrifugal Dewatering of Mineral Slurries. Minerals 2022, 12, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, L.; Geng, D.; Shao, H.; Wang, H.; Tao, D.; Liu, Z.; Bilal, M. Flocculation and filtration performance of coal slime water: Role of flocculant molecular weight and coagulants. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2025, 2492718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Tian, C.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, Q.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, N.; Li, Z.; Liu, D. Plasma pretreatment to enhance the sedimentation of ultrafine kaolinite particles: Experiments and mechanisms. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 59, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Chen, J. Separation performance and centrifugal characteristics of a cascade dewatering equipment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 360, 131075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, J.; Lai, W.; Li, M.; Huo, B. Microstructure and mechanical behaviors of coal gangue—Coal slime water backfill cementitious materials. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 3772–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Meng, L.; Shen, X. Study on ultrasonic-electrochemical treatment for difficult-to-settle slime water. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2020, 64, 104978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, Q.; Cao, J.; Wang, C.; Kuang, Y. Evaluation of the effect of hydraulic shear intensity on coal-slime water flocculation in a gradient fluidized bed. Powder Technol. 2020, 360, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, Q.; Hao, Y. New insights into coal slime water in backfill materials: A fundamental study of pretreatment methods to enhance curing time. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 135924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Lai, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Z.; Li, M.; Zhou, N. Mechanical properties and micro characterization of coal slime water-based cementitious material-gangue filling: A novel method for co-treatment of mining waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wei, L.; Meng, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhai, S.; Lu, J. A study on the mechanism of calcium ion in promoting the sedimentation of illite particles. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 42, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Min, F.; Liu, L. The complexation color development—Visible spectrophotometry method for rapid determination of Ca2+ concentration in mine wastewater and its mechanism. Microchem. J. 2024, 203, 110852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Lu, F. Study on the adsorption mechanism of ricinoleate and oleate on kaolinite and quartz surfaces. Miner. Eng. 2025, 232, 109544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massinaei, M.; Shabani, M.; Alidokht, M. Optimizing the tailings dewatering circuit in a coal preparation plant through industrial trials. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 77, 108604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J. Micro-scale mechanism of sealed water seepage and thickening from tailings bed in rake shearing thickener. Miner. Eng. 2021, 173, 107043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Xiao, B.; Nie, J.; Liu, M. Initial commissioning parameters research of full-tailings backfill system in metal mine: From laboratory tests to industrial operation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 472, 140811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhou, F.; Fu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, C.; Yuan, H.; Yu, S. Study on the separation performance of a decanter centrifuge used for dewatering coal water slurry. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 195, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Shang, X.; Qi, H.; Liu, Y. Analysis of settling efficiency and structural optimization of settling tank. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2025, 218, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angle, C.W.; Gharib, S. Effects of sand and flocculation on dewaterability of kaolin slurries aimed at treating mature oil sands tailings. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2017, 125, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valuev, D.V.; Golik, V.I.; Israilov, R.Y. Optimal Settling Tank Treatment of Coal Mine Wastewater. Coke Chem. 2025, 67, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chen, X.; Nicholson, T.; Peng, Y. The effect of saline water on the settling of coal slurry and coal froth. Powder Technol. 2019, 344, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, B.; Wei, D.; Song, Z.; He, Y.; Bayly, A.E. CFD simulation of tailings slurry thickening in a gravity thickener. Powder Technol. 2021, 392, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Salimi, H.; Zeynali, R.; Akbari, S. Enhancing an industrial feedwell design and operation using computational fluid dynamics. Comput. Part. Mech. 2023, 11, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Revankar, S.; Qi, X.; Guo, Q. Exploring on a three-fluid Eulerian-Eulerian-Eulerian approach for the prediction of liquid jet atomization. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 195, 117160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X. Comparative Analysis of Horizontal Vibrating Centrifuge and Vertical Scraper Centrifuge. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2403, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailler, R.; Ponce de léon, M.; Rocher, V.; Ginisty, P. Application of a laboratory screw decanter to evaluate sludge behaviour in mechanical thickening and dewatering: Preliminary results. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peichao, C.; Dong, Z.; Wenbin, L.; Murong, D. Structural optimization of mining decanter centrifuge based on response surface method and multi-objective genetic algorithm. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2025, 212, 110276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhou, F.; Fu, S.; Hu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, K.; Zhang, S. Optimization and test study of centripetal pump in disc-stack centrifuge based on flow field analysis. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2023, 153, 105200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tao, Y.; Ma, F. Application of Falcon centrifuge in the separation of siliceous phosphate ore. Part. Sci. Technol. 2022, 40, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginisty, P.; Mailler, R.; Rocher, V. Sludge conditioning, thickening and dewatering optimization in a screw centrifuge decanter: Which means for which result? J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 280, 11745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, M.; He, J.; Guo, B.; Liu, L.; Yu, A. Eulerian–Eulerian modeling of the formation and deposition of SiO2 in the outside vapor deposition process. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 449, 137783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.-F.; Xu, K.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.-S.; Peng, M.-G.; Du, H.; Cao, S.-C.; Ma, Q.-L.; Zhou, S.-d.; Song, S.-F. Numerical simulation analysis of stable flow of hydrate slurry in gas-liquid-solid multiphase flow. Ocean Eng. 2024, 300, 117336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Garcia, D.; Cilliers, J.J.; Brito-Parada, P.R. CFD modelling of particle classification in mini-hydrocyclones. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 251, 117253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsuo, H.; Hitoshi, F.; Makoto, I.; Jung-Seock, K. Theoretical analysis of flow characteristics of multiphase mixtures in a vertical pipe. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1998, 24, 539–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yuan, H.; Mei, N.; Yan, Z. Estimation of solid concentration in solid–liquid two-phase flow in horizontal pipeline using inverse problem approach. Particuology 2021, 62, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, F.; Fall, I.; Zhang, D. Experimental and CFD evaluation of bubble diameter and turbulence model influence on nonlinear flow dynamics in vertical columns: A comparative study. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 196, 116421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazhenko, V.; Mochalin, I. Numerical simulation and experimental tests of the filter with a rotating cylindrical perforated filter element. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2020, 235, 2180–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazhenko, V.; Qiu, Y.; Mochalin, I.; Zhu, G.; Cai, J.-C.; Wang, D. Study of hydraulic oil filtration process from solid admixtures using rotating perforated cylinder. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2022, 141, 104578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.X.; Zhang, Y.H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.L.; Li, H.; Du, J.Q.; Lv, W.J.; Li, J.P.; Fu, P.B.; Wu, J.W. Effect of particle self-rotation on separation efficiency in mini-hydrocyclones. Powder Technol. 2022, 399, 117165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Fan, H.; Cheng, W.; Shao, C. Investigation on wear induced by solid-liquid two-phase flow in a centrifugal pump based on EDEM-Fluent coupling method. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2024, 96, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Su, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, B.; Zhe, L.; Zhu, Z. Characterization of particle motion of a double-row hydraulic sluicing collector for deep-sea mining. Ocean Eng. 2024, 309, 118584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Tian, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, G. Three-dimensional Reverse Modeling and Hydraulic Analysis of the Intake Structure of Pumping Stations on Sediment-laden Rivers. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 37, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, D.; Suzuki, Y. Numerical investigation of multiphase feature in a polydisperse gas-solid flow: Effect of particle size, volume fraction and shape. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 159, 108151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Ma, Z.; Wang, H. Investigation of wet particle drying process in a fluidized bed dryer by CFD simulation and experimental measurement. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 452, 139200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).