Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma—A Systematic Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

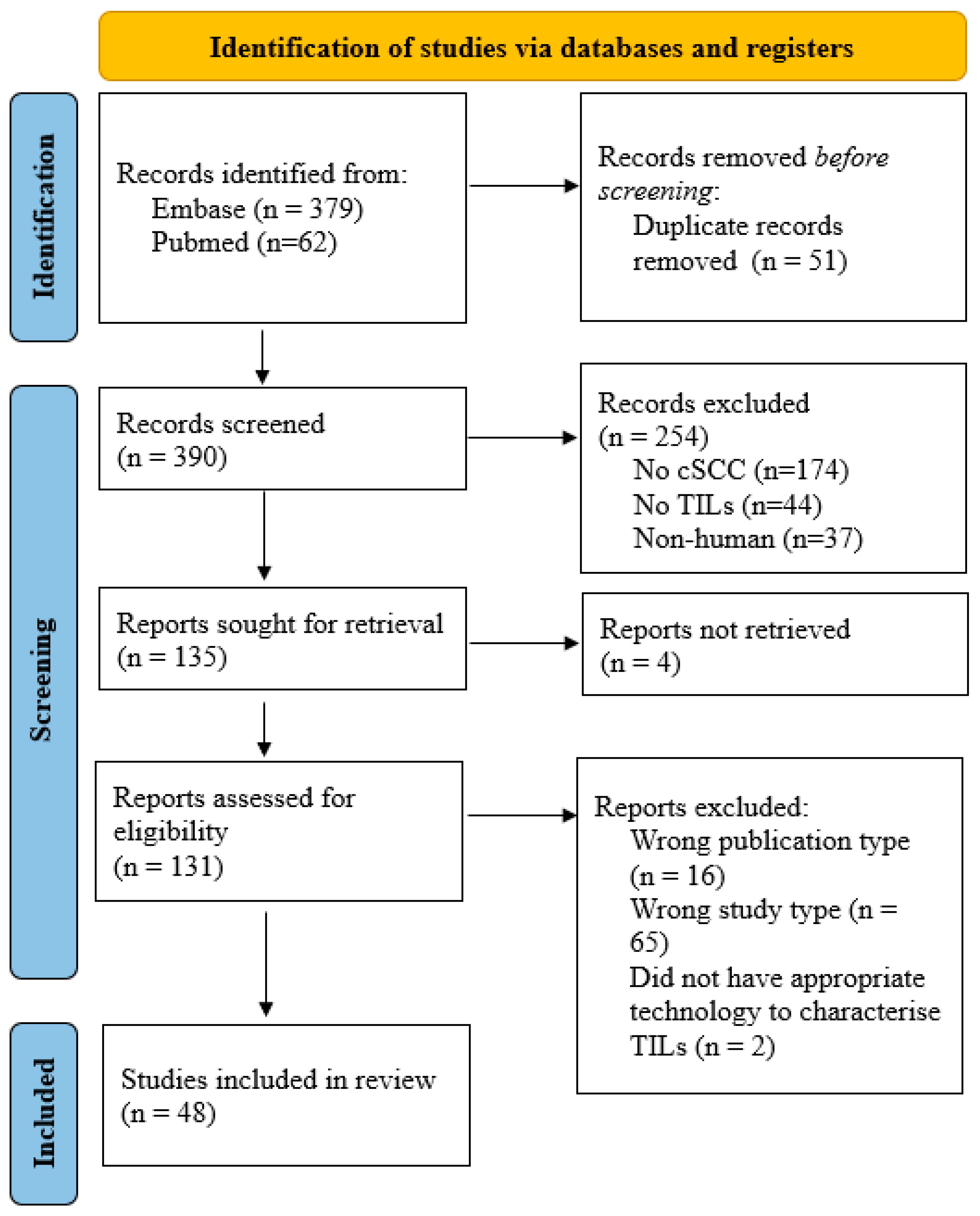

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.2. Comparison of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Between Immunocompetent and Immunosuppressed Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.2.1. Overall TIL Density

3.2.2. Subtype Composition

3.2.3. Checkpoint Expression and Activation

3.2.4. Spatial and Functional Observations

3.3. External Modulators of the Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Landscape in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.3.1. Co-Stimulatory Checkpoint Targeting (OX40+ Tregs)

3.3.2. In Situ HPV Vaccination

3.3.3. Topical Immune Stimulation (Imiquimod)

3.3.4. In Situ Vaccination and Immune Checkpoint Synergy

3.3.5. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) and TIL Exclusion

3.3.6. TGF-β2 and Stromal Immuno-Exclusion

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of the cSCC Tumor Immune Landscape

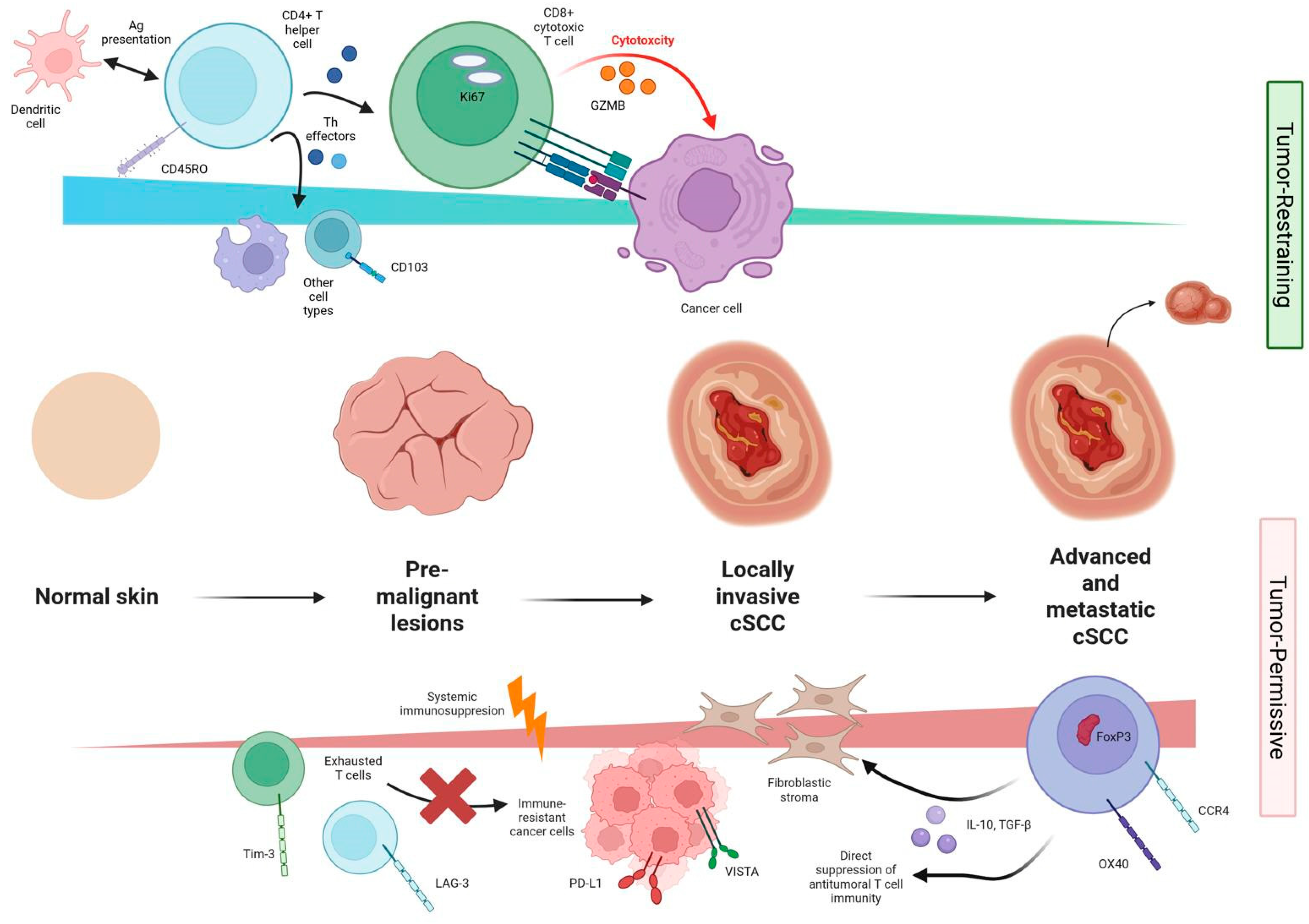

4.2. Tumor-Restraining Immune Subsets and Mechanisms

4.3. Tumor-Permissive Immune Subsets and Immunosuppressive Mechanisms

4.4. Integrating Immune Competence and Microenvironmental Context

4.5. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cSCC | Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| TIL | Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| CD | Cluster of Differentiation |

| CCR | C-C Chemokine Receptor |

| FOXP3 | Forkhead box P3 |

| TGF | Transforming Growth Factor |

| PD-1 | Programmed Death |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death Ligand |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| OX40 | Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Superfamily Member 4 |

| TME | Tumor Micro-environment |

| Treg | Regulatory T-cells |

| LAG-3 | Lymphocyte Activation Gene 3 |

| VISTA | V-domain Immunoglobulin Suppressor of T-cell Activation |

| ICI | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 |

| TCR | T-Cell Receptor |

| CAR | Chimeric Antigen Receptor |

| INPLASY | International Platform of Registered Systematic review and meta-analysis protocols |

| GzmB | Granzyme B |

| TRM | Tissue-Resident Memory T-cells |

| EM | Effector Memory |

| EB | Epidermolysis Bullosa |

| DC | Dendritic Cell |

| CXCL | C-X-C motif chemokine Ligand |

| NET | Neutrophil Extracellular Traps |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-γ |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| Th1 | T helper type 1 |

| COPB2 | Coatomer Protein Complex Subunit Beta 2 |

References

- Que, S.K.T.; Zwald, F.O.; Schmults, C.D. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Incidence, risk factors, diagnosis and staging. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fania, L.; Didona, D.; Di Pietro, F.R.; Verkhovskaia, S.; Morese, R.; Paolino, G.; Donati, M.; Ricci, F.; Coco, V.; Ricci, F.; et al. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: From Pathophysiology to Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, V.; Doudican, N.; Carucci, J.A. Understanding the squamous cell carcinoma immune microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1084873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.-H.; Li, N. Immune evasion in cancer: Mechanisms and cutting-edge therapeutic approaches. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakobson, A.; Abu Jama, A.; Abu Saleh, O.; Michlin, R.; Shalata, W. PD-1 Inhibitors in Elderly and Immunocompromised Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaddour, K.; Murakami, N.; Ruiz, E.S.; Silk, A.W. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Patients with Solid-Organ-Transplant-Associated Immunosuppression. Cancers 2024, 16, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Yan, C.; Xu, Y.; Li, D.; Guo, M.; Sun, L.; Zhu, Z. Allograft rejection following immune checkpoint inhibitors in solid organ transplant recipients: A safety analysis from a literature review and a pharmacovigilance system. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 5181–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch Hein, E.C.; Vilbert, M.; Hirsch, I.; Fernando Ribeiro, M.; Muniz, T.P.; Fournier, C.; Abdulalem, K.; Saldanha, E.E.; Martinez, E.; Spreafico, A.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Advanced Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Real-World Experience from a Canadian Comprehensive Cancer Centre. Cancers 2023, 15, 4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.K.; Komanduri, K.V. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Therapy for the Treatment of Metastatic Melanoma. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2025, 26, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, S.L.; Stevanović, S.; Adhikary, S.; Gartner, J.J.; Jia, L.; Kwong, M.L.M.; Faquin, W.C.; Hewitt, S.M.; Sherry, R.M.; Yang, J.C.; et al. T-Cell Receptor Gene Therapy for Human Papillomavirus–Associated Epithelial Cancers: A First-in-Human, Phase I/II Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2759–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierson, D.J. How to read a case report (or teaching case of the month). Respir. Care 2009, 54, 1372–1378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Awad, A.; Goh, M.S.; Trubiano, J.A. Drug Reaction With Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms: A Systematic Review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 1856–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terao, H.; Nakayama, J.; Urabe, A.; Hori, Y. Immunohistochemical Characterization of Cellular Infiltrates in Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Bowen’s Disease Occurring in One Patient. J. Dermatol. 1992, 19, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelb, A.B.; Smoller, B.R.; Warnke, R.A.; Picker, L.J. Lymphocytes infiltrating primary cutaneous neoplasms selectively express the cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA). Am. J. Pathol. 1993, 142, 1556–1564. [Google Scholar]

- Haeffner, A.C.; Zepter, K.; Elmets, C.A.; Wood, G.S. Analysis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Arch. Dermatol. 1997, 133, 585–590. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Bian, X.; Zhang, L.; Lu, L.; Pei, S.; Dong, L.; Shi, W.; Huang, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. Signatures of EMT, immunosuppression, and inflammation in primary and recurrent human cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma at single-cell resolution. Theranostics 2022, 12, 7532–7549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, J.; Ozog, D.; Loveless, I.; Adrianto, I.; Dimitrion, P.; Subedi, K.; Friedman, B.J.; Zhou, L.; Mi, Q.S. Distinguishing Keratoacanthoma from Well-Differentiated Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Using Single-Cell Spatial Pathology. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 143, 2397–2407.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.-D.; Sun, Y.-Z.; Li, X.-J.; Wu, W.-J.; Xu, D.; He, Y.-T.; Qi, J.; Tu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Tu, Y.H.; et al. Single-cell sequencing highlights heterogeneity and malignant progression in actinic keratosis and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. eLife 2023, 12, e85270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stravodimou, A.; Tzelepi, V.; Papadaki, H.; Mouzaki, A.; Georgiou, S.; Melachrinou, M.; Kourea, E.P. Evaluation of T-lymphocyte subpopulations in actinic keratosis, in situ and invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2018, 45, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, C.; Abdul Pari, A.A.; Umansky, V.; Utikal, J.; Boukamp, P.; Augustin, H.G.; Goerdt, S.; Géraud, C.; Felcht, M. T-lymphocyte profiles differ between keratoacanthomas and invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the human skin. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, R.; Ritter, N.; Hein, R.; Biedermann, T.; Al-Sisi, M.; Eyerich, K.; Garzorz-Stark, N.; Andres, C. Toll-Like Receptor 7 Staining in Malignant Epithelial Tumors. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2017, 39, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satchell, A.C.; Barnetson, R.S.; Halliday, G.M. Increased Fas ligand expression by T cells and tumour cells in the progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 151, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stravodimou, A.; Tzelepi, V.; Balasis, S.; Georgiou, S.; Papadaki, H.; Mouzaki, A.; Melachrinou, M.; Kourea, E.P. PD-L1 Expression, T-lymphocyte Subpopulations and Langerhans Cells in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Precursor Lesions. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 3439–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidacki, M.; Cho, C.; Lopez-Giraldez, F.; Huang, B.; He, J.; Gaule, P.; Chen, L.; Vesely, M.D. PD-1H (VISTA) Expression in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Is Correlated with T-Cell Infiltration and Activation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 145, 2313–2324.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, E.; Lum, T.; Palme, C.E.; Ashford, B.; Ch’ng, S.; Ranson, M.; Boyer, M.; Clark, J.; Gupta, R. PD-L1 expression predicts longer disease free survival in high risk head and neck cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Pathology 2017, 49, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaper, K.; Köther, B.; Hesse, K.; Satzger, I.; Gutzmer, R. The pattern and clinicopathological correlates of programmed death-ligand 1 expression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 176, 1354–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Peng, L.; Huang, K.; Qu, S.; Li, D.; Yao, J.; Yang, F.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, S. Single cell transcriptomics reveals dysregulated immnue homeostasis in different stages in HPV-induced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e15178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; August, S.; Albibas, A.; Behar, R.; Cho, S.-Y.; Polak, M.E.; Theaker, J.; MacLeod, A.S.; French, R.R.; Glennie, M.J.; et al. OX40+ Regulatory T Cells in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Suppress Effector T-Cell Responses and Associate with Metastatic Potential. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4236–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, V.; Ioffe, O.B.; Bentzen, S.M.; Heath, J.; Cellini, A.; Feliciano, J.; Zandberg, D.P. PD-L1, B7-H3, and PD-1 expression in immunocompetent vs. immunosuppressed patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, L.-M.H.; Weishaupt, C.; Schedel, F. Evidence of Neutrophils and Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Human NMSC with Regard to Clinical Risk Factors, Ulceration and CD8+ T Cell Infiltrate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, R.A.; Huang, S.J.; Murphy, G.F.; Mollet, I.G.; Hijnen, D.; Muthukuru, M.; Schanbacher, C.F.; Edwards, V.; Miller, D.M.; Kim, J.E.; et al. Human squamous cell carcinomas evade the immune response by down-regulation of vascular E-selectin and recruitment of regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 2221–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmeyer, L.; Ching, G.; Vin, H.; Ma, W.; Bansal, V.; Chitsazzadeh, V.; Jahan-Tigh, R.; Chu, E.Y.; Fuller, P.; Maiti, S.; et al. Differential T-cell subset representation in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma arising in immunosuppressed versus immunocompetent individuals. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 25, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, A.P.; Bailey, A.; Jones, L.; Turner, R.J.; Hollowood, K.; Ogg, G.S. p53-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in individuals with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005, 153, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousin, F.; Baldassini, S.; Bourchany, D.; Claudy, A.; Kanitakis, J. Expression of the pro-apoptotic caspase 3/CPP32 in cutaneous basal and squamous cell carcinomas. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2000, 27, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, J.; Hajjami, H.M.-E.; Rusakiewicz, S.; Ioannidou, K.; Piazzon, N.; Miles, A.; Golshayan, D.; Gaide, O.; Hohl, D.; Speiser, D.E.; et al. Mutually exclusive lymphangiogenesis or perineural infiltration in human skin squamous-cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, S.; Kato, J.; Kamiya, T.; Yamashita, T.; Sumikawa, Y.; Hida, T.; Horimoto, K.; Sato, S.; Takahashi, H.; Sawada, M.; et al. Association between PD-L1 expression and lymph node metastasis in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 16, e108–e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, S.B.; Safferling, K.; Lahrmann, B.; Hoffmann, J.H.; Enk, A.H.; Hadaschik, E.N.; Grabe, N.; Lonsdorf, A.S. Altered density, composition and microanatomical distribution of infiltrating immune cells in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of organ transplant recipients. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazzette, N.; Khodadadi-Jamayran, A.; Doudican, N.; Santana, A.; Felsen, D.; Pavlick, A.C.; Tsirigos, A.; Carucci, J.A. Decreased cytotoxic T cells and TCR clonality in organ transplant recipients with squamous cell carcinoma. npj Precis. Oncol. 2020, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Coltart, G.; Shapanis, A.; Healy, C.; Alabdulkareem, A.; Selvendran, S.; Theaker, J.; Sommerlad, M.; Rose-Zerilli, M.; Al-Shamkhani, A.; et al. CD8+CD103+ tissue-resident memory T cells convey reduced protective immunity in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e001807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipmann, S.; Wermker, K.; Schulze, H.-J.; Kleinheinz, J.; Brunner, G. Cutaneous and oral squamous cell carcinoma–dual immunosuppression via recruitment of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and endogenous tumour FOXP3 expression? J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 42, 1827–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furudate, S.; Fujimura, T.; Kambayashi, Y.; Haga, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Aiba, S. Immunosuppressive and Cytotoxic Cells in Invasive vs. Non-invasive Bowen’s Disease. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2014, 94, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Slater, N.A.; Sayed, C.J.; Googe, P.B. PD-L1 and LAG -3 expression in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2020, 47, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitley, M.J.; Suwanpradid, J.; Lai, C.; Jiang, S.W.; Cook, J.L.; Zelac, D.E.; Rudolph, R.; Corcoran, D.L.; Degan, S.; Spasojevic, I.; et al. ENTPD1 (CD39) Expression Inhibits UVR-Induced DNA Damage Repair through Purinergic Signaling and Is Associated with Metastasis in Human Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 2509–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dany, M.; Doudican, N.; Carucci, J. The Novel Checkpoint Target Lymphocyte-Activation Gene 3 Is Highly Expressed in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Dermatol. Surg. 2023, 49, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambichler, T.; Gnielka, M.; Rüddel, I.; Stockfleth, E.; Stücker, M.; Schmitz, L. Expression of PD-L1 in keratoacanthoma and different stages of progression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2017, 66, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Díez, I.; Hernández-Ruiz, E.; Andrades, E.; Gimeno, J.; Ferrándiz-Pulido, C.; Yébenes, M.; García-Patos, V.; Pujol, R.M.; Hernández-Muñoz, I.; Toll, A. PD-L1 Expression is Increased in Metastasizing Squamous Cell Carcinomas and Their Metastases. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2018, 40, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoils, M.; Kim, J.; Lee, C.; Sunwoo, J.B.; Colevas, A.D.; Aasi, S.Z.; Hollmig, S.T.; Ma, Y.; Divi, V. PD-L1 Expression and Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in High-Risk and Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Otolaryngol.–Head. Neck Surg. 2019, 160, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, H.; Kondo, Y.; Kusaba, T.; Kawamura, K.; Oyama, Y.; Daa, T. CD8/PD-L1 immunohistochemical reactivity and gene alterations in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Kim, K.-Y.; Oh, Y.; Jeung, H.C.; Chung, K.Y.; Roh, M.R.; Zhang, X. Implication of COPB2 Expression on Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Pathogenesis. Cancers 2022, 14, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, K.E.; Satpathy, A.T.; Wells, D.K.; Qi, Y.; Wang, C.; Kageyama, R.; McNamara, K.L.; Granja, J.M.; Sarin, K.Y.; Brown, R.A.; et al. Clonal replacement of tumor-specific T cells following PD-1 blockade. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalieri, S.; Perrone, F.; Milione, M.; Bianco, A.; Alfieri, S.; Locati, L.D.; Bergamini, C.; Resteghini, C.; Galbiati, D.; Platini, F.; et al. PD-L1 Expression in Unresectable Locally Advanced or Metastatic Skin Squamous Cell Carcinoma Treated with Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Agents. Oncology 2019, 97, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafzadeh, S.; Foreman, R.K.; Kalra, S.; Mandinova, A.; Asgari, M.M. Patterns of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Used to Distinguish Primary Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas That Metastasize. JAMA Dermatol. 2023, 159, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, F.R.; Miles, J.A.; Farag, S.W.; Johnson, E.F.; Davis, M.; Hamzavi, I.H.; Lyons, A.B.; Sayed, C.J.; Googe, P.B. Characterizing the immune checkpoint marker profiles of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, E316–E318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, S.; Cui, H. METTL3-mediated HPV vaccine enhances the effect of anti PD-1 immunotherapy to alleviate the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Bras. Dermatol. 2024, 99, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, K.M.; Deutsch, J.S.; Chandra, S.; Davar, D.; Eroglu, Z.; Khushalani, N.I.; Luke, J.J.; Ott, P.A.; Sosman, J.A.; Aggarwal, V.; et al. Nivolumab + Tacrolimus + Prednisone ± Ipilimumab for Kidney Transplant Recipients With Advanced Cutaneous Cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafei-Shamsabadi, D.; Scholten, L.; Lu, S.; Castiglia, D.; Zambruno, G.; Volz, A.; Arnold, A.; Saleva, M.; Martin, L.; Technau-Hafsi, K.; et al. Epidermolysis-Bullosa-Associated Squamous Cell Carcinomas Support an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment: Prospects for Immunotherapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottomley, M.J.; McKenna, M.; Li, Z.; Zibandeh, N.; Kumaran, G.; Hamid, M.A.; Antoun, E.; Ieremia, E.; Lisboa, L.B.; Van, T.M.; et al. Localised signalling networks co-opt TGF-β2 to promote an immuno-exclusive mesenchymal niche within human squamous cell carcinoma. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.J.; Hijnen, D.; Murphy, G.F.; Kupper, T.S.; Calarese, A.W.; Mollet, I.G.; Schanbacher, C.F.; Miller, D.M.; Schmults, C.D.; Clark, R.A. Imiquimod Enhances IFN-γ Production and Effector Function of T Cells Infiltrating Human Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 2676–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-W.; Kuo, C.-L.; Wang, L.-T.; Ma, K.S.-K.; Huang, W.-Y.; Liu, F.-C.; Yang, K.D.; Yang, B.H. Case Report: In Situ Vaccination by Autologous CD16+ Dendritic Cells and Anti-PD-L 1 Antibody Synergized With Radiotherapy To Boost T Cells-Mediated Antitumor Efficacy In A Psoriatic Patient With Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 752563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W.-T.; Yu, C.-L.; Lan, C.-C.E.; Lee, C.-H.; Chang, C.-H.; Chang, L.W.; You, H.L.; Yu, H.S. Differential effects of arsenic on cutaneous and systemic immunity: Focusing on CD4+ cell apoptosis in patients with arsenic-induced Bowen’s disease. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viac, J.; Schmitt, D.; Claudy, A.; Bustamante, R.; Perrot, H.; Thivolet, J. Immunological and immunocytochemical studies of the inflammatory infiltrating cells of cutaneous tumors. Ann. Immunol. 1977, 128, 109–110. [Google Scholar]

- De Panfilis, G.; Colli, V.; Manfredi, G.; Misk, I.; Rima, S.; Zampetti, M.; Allegra, F. In situ identification of mononuclear cells infiltrating cutaneous carcinoma: An immuno-histochemical study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1979, 59, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S.A.; Spiess, P.; Lafreniere, R. A New Approach to the Adoptive Immunotherapy of Cancer with Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes. Science 1986, 233, 1318–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.L.; Buzzai, A.; Rautela, J.; Hor, J.L.; Hochheiser, K.; Effern, M.; McBain, N.; Wagner, T.; Edwards, J.; McConville, R.; et al. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells promote melanoma–immune equilibrium in skin. Nature 2019, 565, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, T.; Yao, C.; Wu, T. Regulation of T cell exhaustion and stemness: Molecular mechanisms and implications for cancer immunotherapy. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2025, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, D.; Napolitano, F.; Maresca, D.C.; Scala, M.; Amato, A.; Belli, S.; Ascione, C.M.; Vallefuoco, A.; Attanasio, G.; Somma, F.; et al. Early assessment of IL8 and PD1+ Treg predicts response and guides treatment monitoring in cemiplimab-treated cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Lü, W.; Zhang, X.; Lü, B. Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ and FOXP3+ lymphocytes before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cervical cancer. Diagn. Pathol. 2018, 13, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordanova, E.S.; Gorter, A.; Ayachi, O.; Prins, F.; Durrant, L.G.; Kenter, G.G.; Van Der Burg, S.H.; Fleuren, G.J. Human Leukocyte Antigen Class I, MHC Class I Chain-Related Molecule A, and CD8+/Regulatory T-Cell Ratio: Which Variable Determines Survival of Cervical Cancer Patients? Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 2028–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, W.; Yan, X.; Jing, L.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y. A reversed CD4/CD8 ratio of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high percentage of CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells are significantly associated with clinical outcome in squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2011, 8, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, S.H.; Oh, C.C. The clinical landscape of HPV vaccination in preventing and treating cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JEADV Clin. Pract. 2025, 4, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, S.H.; Oh, C.C. T Cell Immunity in Human Papillomavirus-Related Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma—A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balermpas, P.; Michel, Y.; Wagenblast, J.; Seitz, O.; Weiss, C.; Rödel, F.; Rödel, C.; Fokas, E. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes predict response to definitive chemoradiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesca, I.; Tunger, A.; Müller, L.; Wehner, R.; Lai, X.; Grimm, M.-O.; Rutella, S.; Bachmann, M.; Schmitz, M. Characteristics of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Prior to and During Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, V.A.B.; Borch, A.; Hansen, M.; Draghi, A.; Spanggaard, I.; Rohrberg, K.; Hadrup, S.R.; Lassen, U.; Svane, I.M. Common phenotypic dynamics of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes across different histologies upon checkpoint inhibition: Impact on clinical outcome. Cytotherapy 2020, 22, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TIL Subtype | Findings in cSCC | Associated Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD3+ T-cells |

|

| [15,16,17,21,22,26,27,34,39,40] |

| CD4+ helper T-cells |

|

| [29,30,31,34,51] |

| CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells |

|

| [26,27,29,30,31,33,38,39,40,42,51] |

| CD103+ TRM cells | Resident memory T-cells with limited effector function |

| [41] |

| FOXP3+ Tregs | Abundant in invasive/metastatic tumors |

| [21,30,33,42,43] |

| CD45RO+ memory T-cells | Dominant memory phenotype |

| [21,34,41] |

| CD69+ activated T-cells | Present in invasive tumors |

| [21,41] |

| CD45RA+/CCR7+ naïve T-cells | Low in the tumor microenvironment |

| [21,34,41] |

| CD27/CD28 subsets | EM1–EM4 heterogeneity in effector memory cells |

| [41] |

| CD39+ exhausted T-cells | Expressed in metastasizing cSCC |

| [45] |

| Tim-3+/LAG-3+ T-cells | Frequently expressed in advanced or recurrent tumors |

| [44,46] |

| PD-L1 (tumor) | Upregulated with progression |

| [25,26,27,28,31,38,47,48,49,50] |

| PD-L1 (lymphocytes) | Found in exhausted cytotoxic T-cells |

| [26,31,44,46] |

| Ki-67+ proliferating T-cells | Present in VISTA- and PD-L1-high tumors |

| [26] |

| GzmB+ cytotoxic T-cells | Parallel increase with Ki-67+ |

| [26] |

| TIL Subtype | Immunocompetent | Immunosuppressed | Differences | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total CD3+ TIL density | Dense intratumoral and stromal infiltration | Sparse, peritumoral localization | ↓ >50% density; altered spatial pattern | [34,39,40,58] |

| CD4+ helper T-cells | Moderate numbers; assist effector activation | Variable; may predominate over CD8+ | CD4:CD8 ratio ↑ in transplant patients | [34,39,40] |

| CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells | Abundant; intratumoral localization | Markedly reduced; peripheral clustering | 2–3× lower density; decreased TCR clonality | [39,40,58] |

| CD103+ TRM | Present; supports local surveillance | Rare; reduced residency markers | Loss of tissue-resident phenotype in immunosuppression | [18,20,41] |

| FOXP3+ Tregs | Present but balanced with cytotoxic cells | Enriched; peritumoral accumulation | ↑ FOXP3+ frequency; FOXP3:CD8 ratio > 1 in EB-SCC | [30,33,39,42,58] |

| CD45RO+ memory T-cells | Predominant memory phenotype | Reduced the memory compartment | ↓ memory/naïve ratio | [34,40] |

| Activation markers (CD69+, Ki-67+, GzmB+) | Frequent in active TILs | Rare or absent | ↓ proliferating and cytotoxic fractions | [26,40] |

| Exhaustion markers (PD-1, CD39, Tim-3, LAG-3) | Moderate expression, reversible | Strong, sustained expression | ↑ exhaustion marker co-expression | [44,45,46,58] |

| PD-L1 expression (tumor) | 40–60% positive; linked to high TIL density | 70–80% positive; not linked to TIL density | ↑ expression, but functionally non-productive | [27,28,31,38,49,53,58] |

| DC/CD11c+ cells | Preserved antigen presentation | Reduced APC numbers | ↓ DCs in transplant cSCC | [39] |

| Spatial architecture | “Inflamed” or “immune-hot” | “Immune-excluded” with stromal trapping | Central exclusion of CD8+ and CD4+ cells | [18,20,26,39] |

| Modulators | Mechanism | Observed Effect on TILs | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| OX40+ Treg modulation | Co-stimulatory checkpoint reversal | OX40 blockade → ↑ IFN-γ secretion, ↑ cytotoxicity, ↓ suppressive Tregs (ex vivo) | [30] |

| Anti PD-1 therapy | Enables new tumor-specific T-cells to enter and expand | Clonal replacement of exhausted CD8+ T-cells from novel clonotypes | [52] |

| HPV vaccination | Vaccine-driven immune priming | ↑ CD8+, CD4+, CD69+, CD11c+, CD163+ infiltration in vaccinated patients | [56] |

| Imiquimod (topical) | TLR7 agonist → ↑ IFN-γ, granzyme, perforin | ↑ CD8+, ↑ GzmB+ TILs; enhanced effector activation | [60] |

| Triple regimen (autologous CD16+ DC + anti-PD-L1 + radiotherapy) | Antigen release + checkpoint blockade synergy | ↑ CD8+, CD4+, Ki-67+, CD69+ infiltration; enhanced tumor regression | [61] |

| Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) | Neutrophil-mediated immune barrier | High NET density → ↓ CD8+ infiltration, ↑ ulceration risk | [32] |

| TGF-β2 signaling | Fibrovascular stromal exclusion; immune suppression | ↑ TGF-β2 correlated with ↓ CD8+, ↑ fibroblast/endothelial niche formation | [59] |

| Tumor-Restraining Elements | Tumor-Permissive Elements |

|---|---|

| CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells (GzmB+, Ki-67+) | FOXP3+ regulatory T-cells (CCR4+, OX40+) |

| CD4+ helper T-cells (IFN-γ+, IL-2+) | TGF-β2-driven fibroblastic stroma |

| CD69+ activated T-cells | PD-L1+, VISTA+, COPB2-high tumor cells |

| CD103+ tissue-resident memory T-cells | Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) |

| PD-1+/TIM-3+ exhausted yet recoverable T-cells | Organ-transplant–associated immunosuppression |

| CD45RO+ effector memory cells | Endogenous tumor FOXP3 expression |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the European Society of Dermatopathology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Loo, L.Y.; Tay, S.H.; Oh, C.C. Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma—A Systematic Review. Dermatopathology 2026, 13, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology13010006

Loo LY, Tay SH, Oh CC. Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma—A Systematic Review. Dermatopathology. 2026; 13(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology13010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoo, Li Yang, Shi Huan Tay, and Choon Chiat Oh. 2026. "Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma—A Systematic Review" Dermatopathology 13, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology13010006

APA StyleLoo, L. Y., Tay, S. H., & Oh, C. C. (2026). Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma—A Systematic Review. Dermatopathology, 13(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology13010006