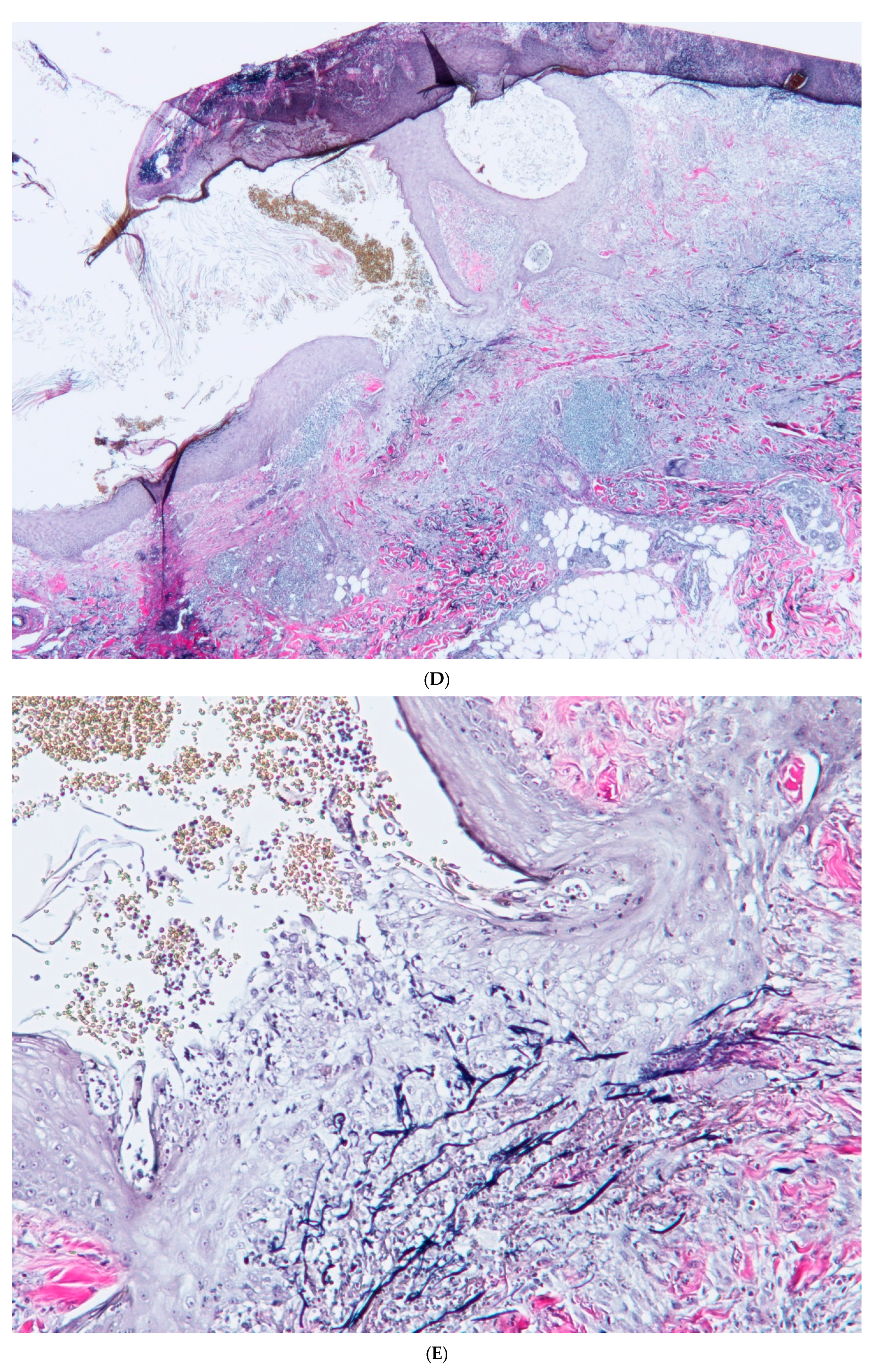

Perforating Granuloma Annulare with Cysts and Comedones

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piette, E.W.; Rosenbach, M. Granuloma annulare: Pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piette, E.W.; Rosenbach, M. Granuloma annulare: Clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, T.P.; Duvi, M. Granuloma annulare: An updated review of epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment options. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayyazi, A.; Schweyer, S.; Eichmeyer, B.; Herms, J.; Hemmerlein, B.; Radzun, H.J.; Berger, H. Expression of IFNgamma, coexpression of TNFalpha and matrix metalloproteinases and apoptosis of T lymphocytes and macrophages in granuloma annulare. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2000, 292, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, M.S.; Wu, J.; He, H.; Sanz-Cabanillas, J.L.; Del Duca, E.; Zhang, N.; Renert-Yuval, Y.; Pavel, A.B.; Lebwohl, M.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Granuloma annulare profile shos activation of T-helper cell type 1, T-helper type 2 and Janus Kinasa pathways. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, A.; Raj, D.; Vinay, K.; Dogra, S. Refractory Generalized Granuloma Annulare Treated with Oral Apremilast. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 1318–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, T.P.; Tschen, J. Apremilast in the Management of Disseminated Granuloma Annulare. Cureus 2021, 13, e14918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.J.; Bezecny, J.; Farrer, S. Recalcitrant generalized granuloma annulare treated successfully with dupilumab. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. Case Rep. 2021, 7, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.J. Tildrakizumab ineffective in generalized granuloma annulare. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. Case Rep. 2021, 7, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Rahman, N.T.; McGeary, M.K.; Murphy, M.; McHenry, A.; Peterson, D.; Bosenberg, M.; Flavell, R.A.; King, B.; Damsky, W. Treatment of granuloma annulare and supression of proinflammatory cytokine activity with tofacitinib. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 1795–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.G.; Sánchez, J.L.; Sánchez, J.E. Palisaded Granuloma on the Nose: An Atypical Presentation of Granuloma Annulare. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2017, 39, e26–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez Peñaranda, J.M.; Aliste, C. Granuloma annulare of the penis: A uncommon location for an usual disease. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2011, 33, e44–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, A.; Liang, J.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y. Linear granuloma annulare localized to the finger. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2020, 86, 314–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Uh, J.A.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, S.K.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, U.H. A Case of Atypical Granuloma Annulare Presenting as Palmoplantar Pustules. Ann. Dermatol. 2023, 35 (Suppl. S1), S126–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhattarwal, N.; Srivastava, P.; Verma, P. Acute onset painful acral granuloma annulare: A new ulcerative variant. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, e683–e684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saigusa, R.; Asano, Y.; Sato, S. Case of disseminated granuloma annulare with giant plaques. J. Dermatol. 2016, 43, 1443–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, R.; Figueiredo, C.; Cardoso, J.C.; Oliveira, H.S. Generalized Papular Granuloma Annulare Presenting with Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum-Like Lesions. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2023, 114, 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, R.; Ibrahim, Y.; Hsieh, A.; Kaya, G. Pseudolymphomatous Granuloma Annulare: A Case Report. Dermatopathology 2020, 7, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas-Velasco, M.; Urquina-Renke, A.; Pérez-Plaza, A.; Fraga, J. Pseudolymphomatous Granuloma Annulare: A Little-Known Variant. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019, 110, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, J.N.; Kalen, J.E.; Hsu, S.; Diwan, A.H.; Calame, A.; Motaparthi, K. Keratoacanthomatous Changes: Unifying the Histologic Spectrum of Actinic Granuloma. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2018, 40, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrade, A.E.; Pitchford, C.A.; Neill, B.C.; Chisholm, C.; Tolkachjov, S.N. Granuloma Annulare Mimicking Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cureus 2022, 14, e27372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, J.P. Actinic granuloma. Arch. Dermatol. 1975, 111, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragaz, A.; Ackerman, A.B. Is actinic granuloma a specific condition? Am. J. Dermatopathol. 1979, 1, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.H.; Murray, S.J.; Walsh, N.M. Evolution of granuloma annulare to mid-dermal elastolysis: Report of a case and review of the literature. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2014, 41, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, F.; Beltran, C.; Miranda, R.; Villaseca, M.A.; Bellolio, E. Anetoderma: Unusual clinical presentation of granuloma annulare. J. Dermatol. 2024, 51, e209–e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudy, E.; Urbina, F.; Espinoza, X. Open comedones overlying granuloma annulare in a photoexposed area. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2006, 22, 273–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, P.; Aggarwal, A.; Yadav, R.; Baliyan, V. Generalized granuloma annulare with open comedones in photoexposed areas. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2011, 36, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavioli, C.F.B.; Valente, N.Y.S.; Sangueza, M.; Nico, M.M. Actinic granuloma annulare with scarring and open comedones. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2017, 39, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensler, M.S.; Hristov, A.C.; Aravind, M.S. Chronic annular plaques with new peripheral folicular plugging. J. Am. Acad. Dermtol. Case Rep. 2024, 49, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Errichetti, E.; Cataldi, P.; Stinco, G. Dermatoscopy in annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, e66–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Yus, E.; del Río, E.; Simón, P.; Requena, L.; Vázquez, H. The histopathology of closed and open comedones of Favre-Racouchout disease. Arch. Dermatol. 1997, 133, 743–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerl, H.; Cerroni, L.; Kokol, R.; Requena, L.; Kutzner, H.; Metze, D.; Fried, I.; Stieber, W.; Wolf, I.H. Drug eruptions. In Diagnostic Cutaneous Pathology: Clinical-Pathological Correlation of Inflammatory and Other Non-Neoplastic Skin Diseases: A Textbook and Atlas, 1st ed.; Verlagshaus Jakomini: Graz, Austria, 2018; pp. 226–290. [Google Scholar]

- Kerl, H.; Cerroni, L.; Kokol, R.; Requena, L.; Kutzner, H.; Metze, D.; Fried, I.; Stieber, W.; Wolf, I.H. Mycobacterial infections, atypical. In Diagnostic Cutaneous Pathology: Clinical-Pathological Correlation of Inflammatory and Other Non-Neoplastic Skin Diseases: A Textbook and Atlas, 1st ed.; Verlagshaus Jakomini: Graz, Austria, 2018; pp. 716–719. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, C.; Alshaikh Elston, D. Dermatology practice updates in mycobacterial disease. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 63, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerl, H.; Cerroni, L.; Kokol, R.; Requena, L.; Kutzner, H.; Metze, D.; Fried, I.; Stieber, W.; Wolf, I.H. Tuberculosis. In Diagnostic Cutaneous Pathology: Clinical-Pathological Correlation of Inflammatory and Other Non-Neoplastic Skin Diseases: A Textbook and Atlas, 1st ed.; Verlagshaus Jakomini: Graz, Austria, 2018; pp. 1149–1156. [Google Scholar]

| Reference/ Year of Publication | Age/Sex | Location of Lesion | Elastophagocytosis/ Type of Multinucleated Giant Cell | Presence of Comedones/ Cysts | Transepithelial Elimination of Elastic Fibers | Associated Diseases | Treatment *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sudy et al., 2006 [26] | 57/F | Forearms | YES/NA | YES/NO | NO | DM | DM therapy |

| Bhushan et al., 2011 [27] | 42/F | Chest *, forearms, forehead | YES/NA | YES/NO | NO | Hypothyroidism DM | DM therapy |

| Gavioli et al., 2017 [28] | 64/M | Forearms | YES/Langhans-type multinucleated cells ** | YES/YES | NO | DM | NA |

| Pensler et al., 2024 [29] | 57/M | Hands, forearms, elbows | NA/NA | YES/NO | NO | Insulin-dependent type II DM | NA |

| Our case | 71/F | Elbows | YES/Langhans-type multinucleated cells | YES/YES | YES | Uncontrolled DM, AH, Hypercholesterolemia | Intralesional steroids |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the European Society of Dermatopathology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piqué-Duran, E.; Azcue-Mayorga, M.; Roque-Quintana, B.; García-Vázquez, O.; Ruedas-Martínez, A. Perforating Granuloma Annulare with Cysts and Comedones. Dermatopathology 2025, 12, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology12020016

Piqué-Duran E, Azcue-Mayorga M, Roque-Quintana B, García-Vázquez O, Ruedas-Martínez A. Perforating Granuloma Annulare with Cysts and Comedones. Dermatopathology. 2025; 12(2):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology12020016

Chicago/Turabian StylePiqué-Duran, Enric, Mikel Azcue-Mayorga, Belinda Roque-Quintana, Odalys García-Vázquez, and Antonio Ruedas-Martínez. 2025. "Perforating Granuloma Annulare with Cysts and Comedones" Dermatopathology 12, no. 2: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology12020016

APA StylePiqué-Duran, E., Azcue-Mayorga, M., Roque-Quintana, B., García-Vázquez, O., & Ruedas-Martínez, A. (2025). Perforating Granuloma Annulare with Cysts and Comedones. Dermatopathology, 12(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology12020016