When Support Hurts: Re-Examining the Cyberbullying Victimization–Mental Health Relationship Among University Students in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations and Hypotheses Formulation

Cyberbullying-Victimization and Mental Health

3. Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Participants

3.3. Procedures

3.4. Data Analysis Techniques

4. Study Results

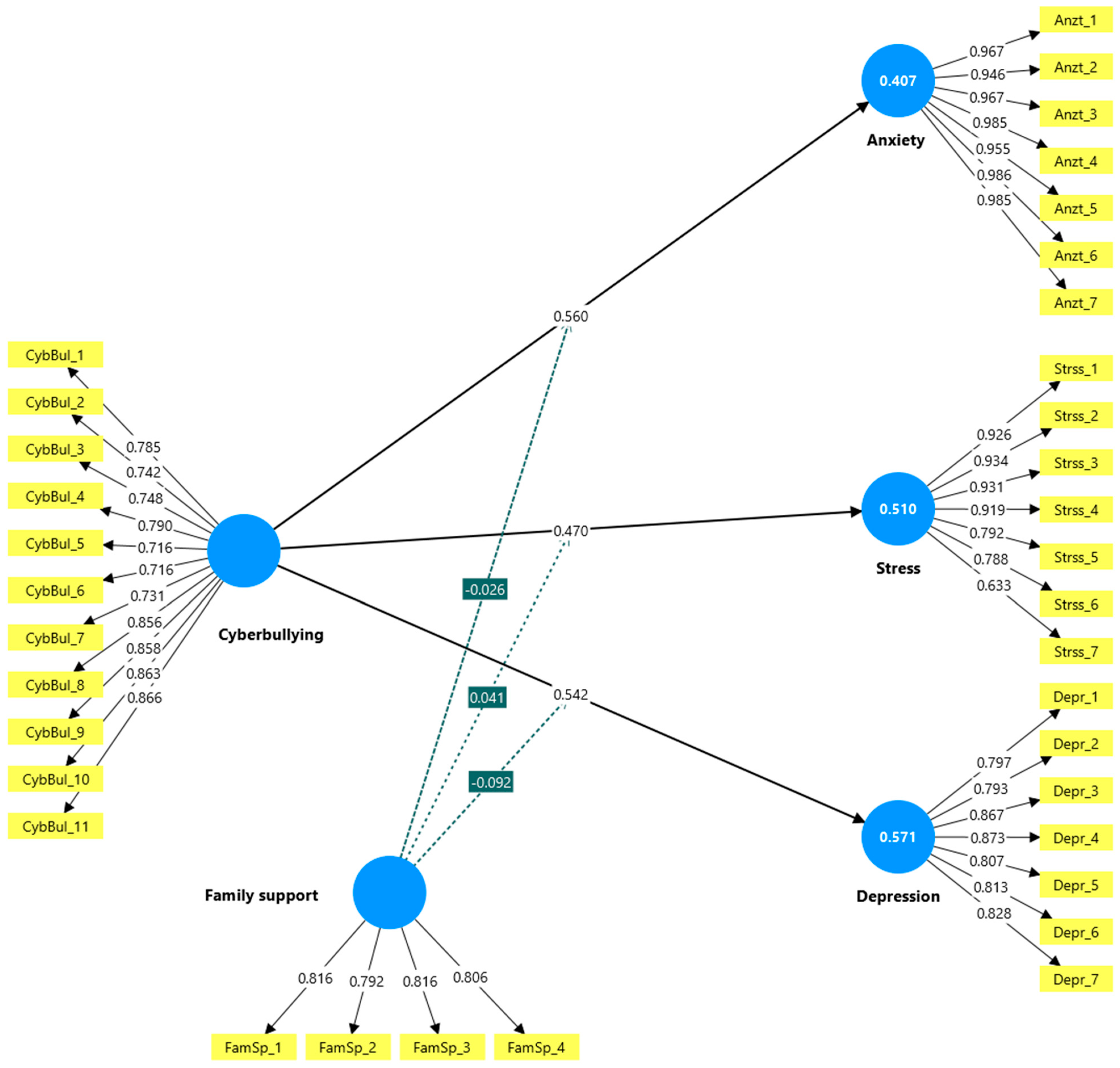

4.1. Stage 1: Measurement Model Results

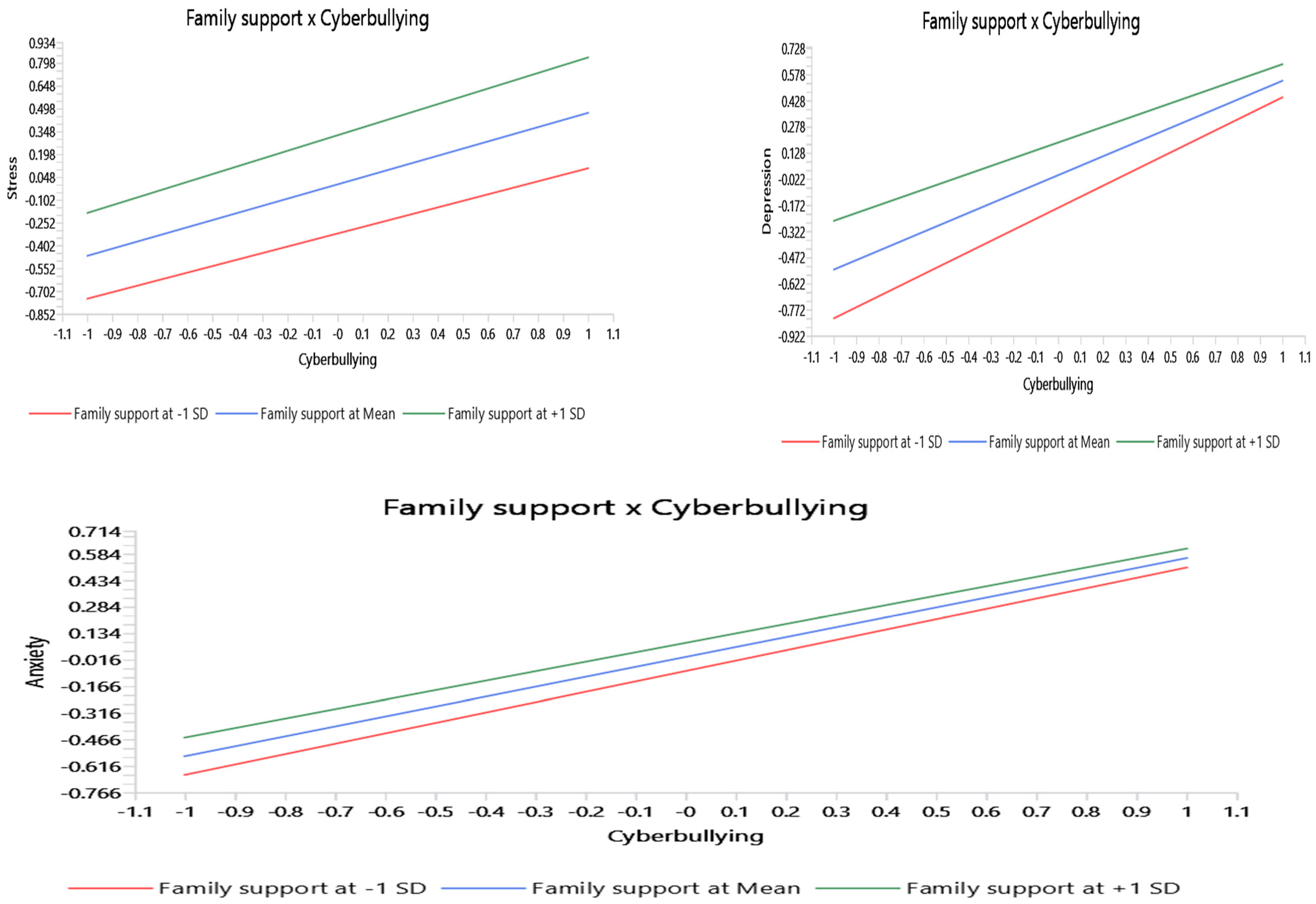

4.2. Stage 2: Inner Model Results and Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboujaoude, E., Savage, M. W., Starcevic, V., & Salame, W. O. (2015). Cyberbullying: Review of an old problem gone viral. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(1), 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A., Schachner, M., Aydnili-Karakulak, A., Alonso-Arbiol, I., Martinez-Fernandez, V., Nyongesa, M. K., & Shauri, H. (2016). Family connectedness and its association with psychological well-being among emerging adults across four cultural contexts. In Positive youth development in global contexts of social and economic change (pp. 137–156). Routledge. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315307275-19/family-connectedness-association-psychological-well-being-among-emerging-adults-across-four-cultural-contexts-amina-abubakar-maja-schachner-arzu-aydnili-karakulak-itziar-alonso-arbiol-virginia-martinez-fernandez-moses-kachama-nyongesa-halimu-shauri (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Agnew, R. (2007). Pressured into crime: An overview of general strain theory. Available online: https://philpapers.org/rec/AGNPIC (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Al-Amer, R. M., Malak, M. Z., Shuhaiber, A. H., Aburoomi, R. J., & Darwish, M. (2025). Cyberbullying and stress, anxiety, and depression among university students: Social support and self-esteem as mediators. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia, 31(4), 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, W., Almadani, S., Banjer, H., Alsulami, D., & Alghamdi, Y. (2025). Relationship between cyberbullying, anxiety, and depression among university students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 60(2), 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, N. H. (2022). Cyberbullying victimization: Adaptation experiences and impact on self-esteem as described by young women in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [Ph.D. thesis, State University of New York at Binghamton]. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/0f017b294c449f75fdb47968141bf4dd/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y&casa_token=BmjGZIlod6wAAAAA:Elx4FdvBXQk6Nu5nEFc_XPfivydGiVsCw2rCPswipXuRr9HT54bh_wr04j6ZzJsQjoGo3SbFgE0 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Almakrob, A. Y., & Alduais, A. (2025). Depression and anxiety in the saudi population: Epidemiological profiles from health surveys and mental health services. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 62, 00469580251382027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabi, S. M., Al-Ababneh, M. M., Al Qsssem, A. H., Afaneh, J. A. A., & Elshaer, I. A. (2024). Green human resource management practices and environmental performance: The mediating role of job satisfaction and pro-environmental behavior. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2328316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, H. G. A., & Awad, I. (2025). The extensive use of social media by Arab university students (gratifications, impact, and risks). Entertainment Computing, 53, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakina, E. Y., Popova, A. V., Gorokhova, S. S., & Voskovskaya, A. S. (2021). Digital technologies and artificial intelligence technologies in education. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 10(2), 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C. P., Simmers, M. M., Roth, B., & Gentile, D. (2021). Comparing cyberbullying prevalence and process before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Social Psychology, 161(4), 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, M., & Li, S. A. (1996). The relation of family support to adolescents’ psychological distress and behavior problems. In G. R. Pierce, B. R. Sarason, & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Handbook of social support and the family (pp. 313–343). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. Haper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H., Wang, S., Zhou, N., & Liang, Y. (2024). From childhood real-life peer victimization to subsequent cyberbullying victimization during adolescence: A process model involving social anxiety symptoms, problematic smartphone use, and internet gaming disorder. Psychology of Violence, 15, 106–120. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2025-15660-001 (accessed on 1 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. K. Y. (2023). A comprehensive AI policy education framework for university teaching and learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Li, Y., Xiong, J., Yu, J., & Wu, T. (2024). Cyberbullying victimization and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among college students: Mediating role of negative coping and moderating role of perceived control. Current Psychology, 43(21), 19294–19303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 655–690). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CST. (2023). CST issued the Saudi internet report 2023. Available online: https://www.cst.gov.sa/en/media-center/news/CST-Issued-The-Saudi-Internet-Report-2023 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Cummings, C. L. (2018). Cross-sectional design. In The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. SAGE Publications Inc. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1YJ1PHUm1ZdveF_5290DIcKMM5DJbG8PZ/view (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Daoud, J. I. (2017). Multicollinearity and regression analysis. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 949(1), 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., Thompson, F., Barkoukis, V., Tsorbatzoudis, H., & Brighi, A. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European cyberbullying intervention project questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dınn, A. A., & Caldwell-harrıs, C. L. (2016). How collectivism and family control influence depressive symptoms in Asian American and European American college students. Elektronik Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 15(57), 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrance Hall, E., & Scharp, K. M. (2021). Communicative predictors of social network resilience skills during the transition to college. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(4), 1238–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwairy, M., & Achoui, M. (2010). Parental control: A second cross-cultural research on parenting and psychological adjustment of children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(1), 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faucher, C., Jackson, M., & Cassidy, W. (2014). Cyberbullying among university students: Gendered experiences, impacts, and perspectives. Education Research International, 2014, 698545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Mohd Adnan, H., & Zainal Abidin, M. Z. (2025). Behind the screen: Exploring perceptions, attitudes, and coping behaviors toward cyberbullying on Douyin among Chinese undergraduates. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., & Alamer, A. (2022). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Computational Statistics, 28(2), 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, B. N., Reynolds, C. A., & Charles, S. T. (2015). Understanding associations among family support, friend support, and psychological distress. Personal Relationships, 22(1), 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, E. (2016). Cyberbullying in adolescence: A concept analysis. Advances in Nursing Science, 39(1), 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE Publications, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Kazimova, D., Tazhigulova, G., Shraimanova, G., Zatyneyko, A., & Sharzadin, A. (2025). Transforming university education with AI: A systematic review of technologies, applications, and implications. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy, 15(1), 4. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=21924880&AN=182283181&h=LKaa8dZTh2h7jLosY%2BCGYSBYfK8bM%2Bb9s1sYjhhCPLjD9aNtEucEinacm0CAXPi0hJCeu%2Fswzqyxq79DdP50pQ%3D%3D&crl=c (accessed on 1 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., & Feinn, R. S. (2023). Is cyberbullying an extension of traditional bullying or a unique phenomenon? A longitudinal investigation among college students. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 5(3), 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. (2022). Sample size justification. Collabra: Psychology, 8(1), 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Choo, H., Zhang, Y., Cheung, H. S., Zhang, Q., & Ang, R. P. (2025). Cyberbullying victimization and mental health symptoms among children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15248380241313051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leguina, A. (2015). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 38(2), 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Liao, X., & Ni, J. (2025). A cross-sectional study of cybervictimization and non-suicidal self-injury among college students: A moderated mediation model of rumination and resilience. Archives of Suicide Research, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Yin, J., Xu, L., Luo, X., Liu, H., & Zhang, T. (2025). The chain mediating effect of anxiety and inhibitory control and the moderating effect of physical activity between bullying victimization and internet addiction in chinese adolescents. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 186(5), 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, O. F., Schat, A. C. H., Shahzad, A., Raziq, M. M., & Faiz, R. (2021). Workplace psychological aggression, job stress, and vigor: A test of longitudinal effects. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(5–6), NP3222–NP3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, L., Schulz, P. J., & Camerini, A.-L. (2020). Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization in youth: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(2), 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, L., Driver, C., McLoughlin, L. T., Anijärv, T. E., Mitchell, J., Lagopoulos, J., & Hermens, D. F. (2024). A systematic review and meta-analysis of electrophysiological studies of online social exclusion: Evidence for the neurobiological impacts of cyberbullying. Adolescent Research Review, 9(1), 135–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M. E., Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M., & Younis, N. S. (2023). Born not made: The impact of six entrepreneurial personality dimensions on entrepreneurial intention: Evidence from healthcare higher education students. Sustainability, 15(3), 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L. I., Menaghan, E. G., Lieberman, M. A., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, C., & Watt, J. D. (2024). The essence of cyberbullying research: An exploratory bibliometric analysis of the contemporary psychological literature. North American Journal of Psychology, 26(2), 253. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=15277143&AN=177229636&h=n69MlGcUZmAvteZn%2FvoKb7AMA4xZX5dKGjvsgfSh7cZXx0L%2Fvo%2B%2Bd2Zp6DHR9RIp9wMaMjQmy8stx2hC69GfzA%3D%3D&crl=c (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Rafaeli, E., & Gleason, M. E. J. (2009). Skilled support within intimate relationships. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 1(1), 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., Moisescu, O. I., & Radomir, L. (2020). Structural model robustness checks in PLS-SEM. Tourism Economics, 26(4), 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2022). Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In C. Homburg, M. Klarmann, & A. Vomberg (Eds.), Handbook of market research (pp. 587–632). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, A. M., & Fremouw, W. J. (2012). Prevalence, psychological impact, and coping of cyberbully victims among college students. Journal of School Violence, 11(1), 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabeeb Ali, M. A., Ammer, M. A., & Elshaer, I. A. (2023). Born to be green: Antecedents of green entrepreneurship intentions among higher education students. Sustainability, 15(8), 6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. V., & Hiran, K. K. (2022). The impact of AI on teaching and learning in higher education technology. Journal of Higher Education Theory & Practice, 12(13), 135. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=21583595&AN=159989843&h=SHIZYrUPyKT1wxtIRkBhD3I4zGsqmLbSEYOQBl1G9LN7W%2F%2FQoOs%2BBDikixpPpd7nLIbFRQyJCApFrAercMA%2FpA%3D%3D&crl=c (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Slonje, R., Smith, P. K., & Frisén, A. (2013). The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snakenborg, J., Van Acker, R., & Gable, R. A. (2011). Cyberbullying: Prevention and intervention to protect our children and youth. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 55(2), 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, A., Sulla, F., Santamato, M., di Furia, M., Toto, G. A., & Monacis, L. (2023). Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected cyberbullying and cybervictimization prevalence among children and adolescents? A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y.-M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 48(1), 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaill, Z., Campbell, M., & Whiteford, C. (2020). Analysing the quality of Australian universities’ student anti-bullying policies. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(6), 1262–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, J. J., Hernández, C., Miranda, R., Barlett, C. P., & Rodríguez-Rivas, M. E. (2022). Victims of cyberbullying: Feeling loneliness and depression among youth and adult Chileans during the pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieta-Piferrer, J., Oriol, X., & Miranda, R. (2024). Longitudinal associations between cyberbullying victimization and cognitive and affective components of subjective well-being in adolescents: A network analysis. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 19(5), 2967–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18(1), 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M. F. (2015). Cyber Victimization and perceived stress: Linkages to late adolescents’ cyber aggression and psychological functioning. Youth & Society, 47(6), 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. F. (2017). Cyber Victimization and depression among adolescents with intellectual disabilities and developmental disorders: The moderation of perceived social support. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 10(2), 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. F. (2024). The moderating effect of parental mediation in the longitudinal associations among cyberbullying, depression, and self-harm among Chinese and American adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1459249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H., Hu, S., & Dai, Z. (2024). Peer-aggressive humor and cyberbullying among Chinese and American university students: Mediating and moderating roles of frustration and peer norms. Studies in Higher Education, 49(12), 2723–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Items | FL | a | CR | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 0.910 | 0.911 | 0.941 | |||

| Anzt_1 | 0.967 | 1.879 | ||||

| Anzt_2 | 0.946 | 2.301 | ||||

| Anzt_3 | 0.967 | 2.155 | ||||

| Anzt_4 | 0.985 | 2.085 | ||||

| Anzt_5 | 0.955 | 3.898 | ||||

| Anzt_6 | 0.986 | 2.150 | ||||

| Anzt_7 | 0.985 | 2.316 | ||||

| Cyberbullying | 0.939 | 0.941 | 0.625 | |||

| CybBul_1 | 0.785 | 1.447 | ||||

| CybBul_10 | 0.863 | 2.988 | ||||

| CybBul_11 | 0.866 | 2.080 | ||||

| CybBul_2 | 0.742 | 3.601 | ||||

| CybBul_3 | 0.748 | 2.175 | ||||

| CybBul_4 | 0.790 | 3.899 | ||||

| CybBul_5 | 0.716 | 2.066 | ||||

| CybBul_6 | 0.716 | 1.827 | ||||

| CybBul_7 | 0.731 | 2.494 | ||||

| CybBul_8 | 0.856 | 1.455 | ||||

| CybBul_9 | 0.858 | 1.008 | ||||

| Depression | 0.922 | 0.922 | 0.682 | |||

| Depr_1 | 0.797 | 1.849 | ||||

| Depr_2 | 0.793 | 2.854 | ||||

| Depr_3 | 0.867 | 2.861 | ||||

| Depr_4 | 0.873 | 2.699 | ||||

| Depr_5 | 0.807 | 3.306 | ||||

| Depr_6 | 0.813 | 3.865 | ||||

| Depr_7 | 0.828 | 1.347 | ||||

| Family Support | 0.823 | 0.825 | 0.652 | |||

| FamSp_1 | 0.816 | 1.766 | ||||

| FamSp_2 | 0.792 | 1.748 | ||||

| FamSp_3 | 0.816 | 1.757 | ||||

| FamSp_4 | 0.806 | 1.655 | ||||

| Stress | 0.934 | 0.937 | 0.727 | |||

| Strss_1 | 0.926 | 3.655 | ||||

| Strss_2 | 0.934 | 1.344 | ||||

| Strss_3 | 0.931 | 3.959 | ||||

| Strss_4 | 0.919 | 3.093 | ||||

| Strss_5 | 0.792 | 3.575 | ||||

| Strss_6 | 0.788 | 3.227 | ||||

| Strss_7 | 0.633 | 1.441 |

| Anxiety | Cyberbullying | Depression | Family Support | Stress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | |||||

| Cyberbullying | 0.653 | ||||

| Depression | 0.484 | 0.791 | |||

| Family support | 0.556 | 0.729 | 0.737 | ||

| Stress | 0.478 | 0.733 | 0.640 | 0.731 |

| Anxiety | Cyberbullying | Depression | Family Support | Stress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 0.970 | ||||

| Cyberbullying | 0.635 | 0.791 | |||

| Depression | 0.465 | 0.637 | 0.826 | ||

| Family support | 0.508 | 0.635 | 0.645 | 0.808 | |

| Stress | 0.458 | 0.682 | 0.590 | 0.642 | 0.853 |

| β | T Statistics | p Values | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyberbullying -> Anxiety | 0.560 | 10.665 | 0.000 | H1-Supported |

| Cyberbullying -> Depression | 0.542 | 10.594 | 0.000 | H2-Supported |

| Cyberbullying -> Stress | 0.470 | 9.695 | 0.000 | H3-Supported |

| Moderation Paths | ||||

| Family support x Cyberbullying -> Anxiety | −0.026 | 0.481 | 0.630 | H4-Rejected |

| Family support x Cyberbullying -> Depression | −0.092 | 2.273 | 0.023 | H5-Rejected |

| Family support x Cyberbullying -> Stress | 0.041 | 0.843 | 0.399 | H6-Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Kooli, C.; Alyahya, M. When Support Hurts: Re-Examining the Cyberbullying Victimization–Mental Health Relationship Among University Students in Saudi Arabia. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2026, 16, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16010007

Elshaer IA, Azazz AMS, Kooli C, Alyahya M. When Support Hurts: Re-Examining the Cyberbullying Victimization–Mental Health Relationship Among University Students in Saudi Arabia. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2026; 16(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Ibrahim A., Alaa M. S. Azazz, Chokri Kooli, and Mansour Alyahya. 2026. "When Support Hurts: Re-Examining the Cyberbullying Victimization–Mental Health Relationship Among University Students in Saudi Arabia" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 16, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16010007

APA StyleElshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Kooli, C., & Alyahya, M. (2026). When Support Hurts: Re-Examining the Cyberbullying Victimization–Mental Health Relationship Among University Students in Saudi Arabia. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 16(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16010007