Health Inequalities in German Higher Education: A Cross-Sectional Study Reveals Poorer Health in First-Generation University Students and University Students with Lower Subjective Social Status

Abstract

1. Introduction

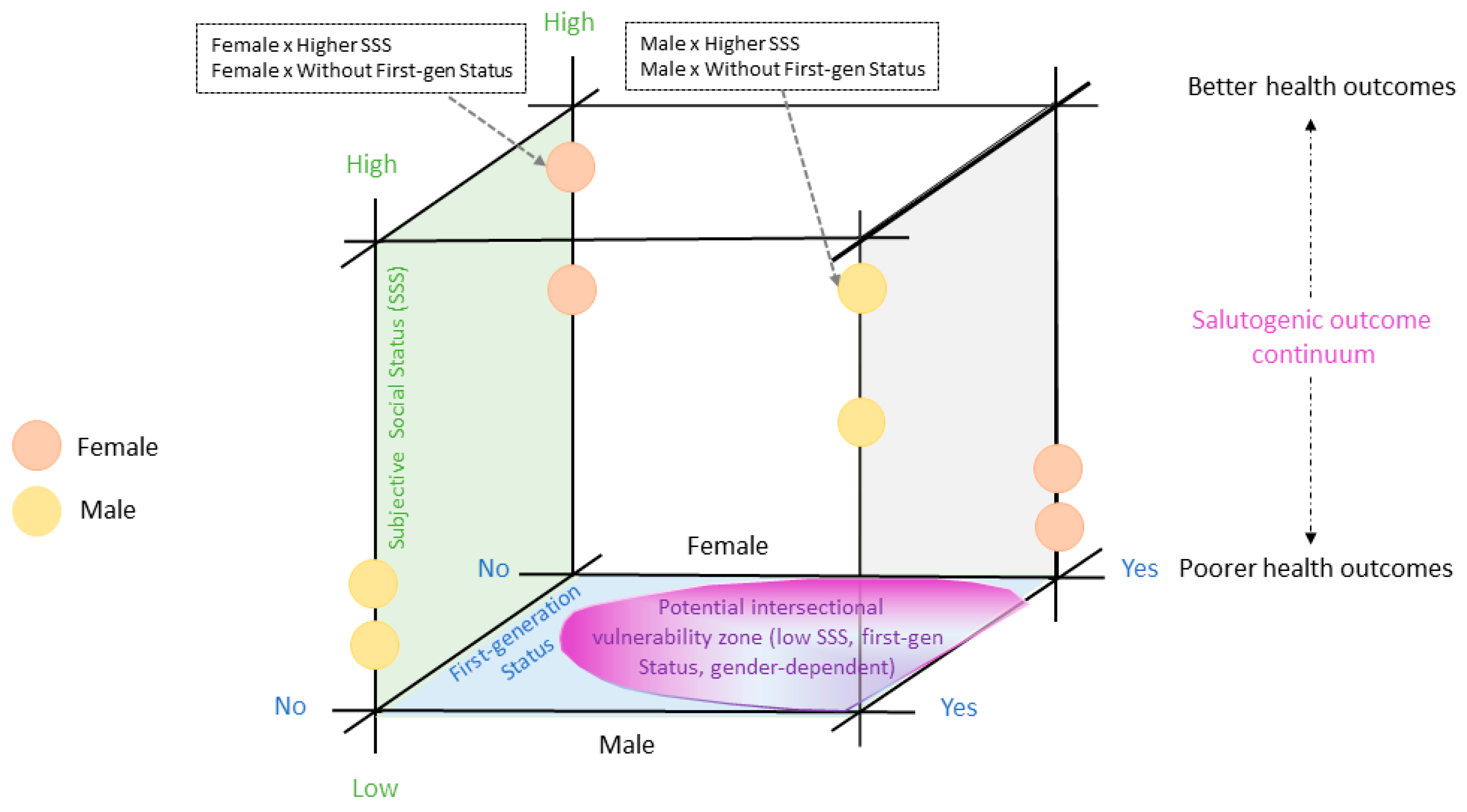

- Gain a broader perspective in line with the salutogenic framework by considering not only the negative health outcomes (stress, depression, burnout), but also the positive ones (self-rated health, well-being).

- Contribute to a more nuanced understanding of students’ health by addressing a subjective dimension (SSS) and an objective dimension (first-gen status) of vertical health inequalities.

- Assess the combined relationships of gender and vertical dimensions to recognize the multifaceted interactions of social determinants in relation to university students’ health. In doing so, the study also advances ongoing efforts to quantitively ground initial indications of intersectional perspectives (LeBouef & Dworkin, 2021).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analyses

- I: unadjusted model (without covariates)

- II: sociodemographic model (adjusted for age, migration background, gender)

- III: socioeconomic model (adjusted for primary source of income, living situation)

- IV: study-related model (adjusted for type of university, area of studies, semester)

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Bivariate Analyses

3.3. Regression Models

3.4. Moderation Analyses Using Interaction Terms

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations for Interventions

- Individual level: Digital mHealth apps provide low-threshold, scalable support for stress management, particularly among students with lower SSS scores (Thomas et al., 2023). When combined with empowerment and stress management programs, these apps can further strengthen coping skills and support-reflection, potentially improving self-image and reducing depressive tendencies (Pössel et al., 2022).

- Social level: Mentoring programs for first-gens may foster resilience and strengthen the sense of belonging (Kamalumpundi et al., 2024). Networking initiatives are also valuable, as they can help students with lower SSS and first-gens expand their connections within academic communities. In addition, burnout prevention initiatives should be implemented in the early semesters to prevent health deterioration over time (Kim, 2022; Liu et al., 2023).

- Institutional level: Financial support for first-gens and students with lower SSS remains essential to ensure equal opportunities in health in higher education. Across all support services, it is important to ensure that students with lower SSS feel supported without experiencing additional obligation or a loss in autonomy (Xin, 2023), while also recognizing that each group, such as first-gens, brings its own strengths (LeBouef & Dworkin, 2021).

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FAU | Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg |

| First-gens | First-generation university students |

| M | Mean |

| MBI-SS | Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey |

| PHQ | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SOS | Stress Overload Scale |

| SRH | Self-Rated Health |

| SSS | Subjective Social Status |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Adler, N., & Stewart, J. (2007). The MacArthur scale of subjective social status. MacArthur Research Network on SES & Health. [Google Scholar]

- Alpizar, D., Plunkett, S. W., & Whaling, K. (2018). Reliability and validity of the 8-item patient health questionnaire for measuring depressive symptoms of latino emerging adults. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 6, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirkhan, J. H. (2012). Stress overload: A new approach to the assessment of stress. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirkhan, J. H., Manalo, R., & Velasco, S. E. (2023). Stress overload in first-generation college students: Implications for intervention. Psychological Services, 20, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis-Farahwahida, M. K., Hussain, S. H. M., Mohd Firdaus Ruslan, M. F., & Raji, N. A. A. (2024). A comparative analysis of gender differences in university student mental health across cultures. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 8, 1774–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., Murray, E., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Stein, D. J., Vilagut, G., Zaslavsky, A. M., Kessler, R. C., & WHO WMH-ICS Collaborators. (2018). WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 127, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhaus, I., Varela, A. R., Khoo, S., Siefken, K., Crozier, A., Begotaraj, E., Fischer, F., Wiehn, J., Lanning, B. A., Lin, P. H., Jang, S. N., Monteiro, L. Z., Al-Shamli, A., La Torre, G., & Kawachi, I. (2020). Associations between social capital and depressive symptoms among college students in 12 countries: Results of a cross-national study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsegyan, V., & Maas, I. (2024). First-generation students’ educational outcomes: The role of parental educational, cultural, and economic capital—A 9-years panel study. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 91, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, T. J., Jr., Lykken, D. T., McGue, M., Segal, N. L., & Tellegen, A. (1990). Sources of human psychological differences: The minnesota study of twins reared apart. Science, 250, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Bloomsbury 3PL. [Google Scholar]

- Brett, C. E., Mathieson, M. L., & Rowley, A. M. (2023). Determinants of wellbeing in university students: The role of residential status, stress, loneliness, resilience, and sense of coherence. Current Psychology, 42, 19699–19708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, K., Wieman, S. M., Van Strien, J. W., & Lindemann, O. (2024). To each their own: Sociodemographic disparities in student mental health. Frontiers Education, 9, 1391067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deindl, C., Diehl, K., Spallek, J., Richter, M., Schüttig, W., Rattay, P., Dragano, N., & Pischke, C. R. (2023). Self-rated health of university students in Germany—The importance of material, psychosocial, and behavioral factors and the parental socio-economic status. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1075142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSalvo, K. B., Bloser, N., Reynolds, K., He, J., & Muntner, P. (2006). Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, K., Hilger-Kolb, J., & Herr, R. M. (2021). Social inequalities in health and health behaviors among university students. Gesundheitswesen, 83, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, K., Hilger-Kolb, J., & Herr, R. M. (2022). Health inequalities among university students. In M. Timmann, T. Paeck, J. Fischer, B. Steinke, C. Dold, M. Preuß, & M. Sprenger (Eds.), Handbuch studentisches gesundheitsmanagement—Perspektiven, impulse und praxiseinblicke (pp. 27–34). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, K., Hoebel, J., Sonntag, D., & Hilger, J. (2017). Subjective social status and its relationship to health and health behavior: Comparing two different scales in university students. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 31, 20170079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, B. M. (2024). The intersectionality of first-generation students and its relationship to inequitable student outcomes. The AIR Professional File, Summer, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, C., Barni, D., Russo, C., Marchetti, V., Angelini, G., & Romano, L. (2022). Students’ burnout at university: The role of gender and worker status. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 11341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellisch, M., Olk, B., Schäfer, T., & Brand-Saberi, B. (2024). Unraveling psychological burden: The interplay of socio-economic status, anxiety sensitivity, intolerance of uncertainty, and stress in first-year medical students. BMC Medical Education, 2024, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, M., & Brady, S. T. (2020). College students’ sense of belonging: A national perspective. Educational Research Review, 49, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumz, A., Erices, R., Brähler, E., & Zenger, M. (2013). Faktorstruktur und gütekriterien der deutschen übersetzung des maslach-burnout-inventars für studierende von schaufeli et al. (MBI-SS). Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie, 63, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haehner, P., Pfeifer, L. S., Jahre, L. M., Luhmann, M., Wolf, O. T., & Frach, L. (2023). Validation of a German version of the stress overload scale and comparison of different time frames in the instructions. Psychological Test Adaptation and Development, 4, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haught, H. M., Rose, J., Geers, A., & Brown, J. A. (2015). Subjective social status and well-being: The role of referent abstraction. The Journal of Social Psychology, 155, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Torrano, D., Ibrayeva, L., Sparks, J., Lim, N., Clementi, A., Almukhambetova, A., Nurtayev, Y., & Muratkyzy, A. (2020). Mental health and well-being of university students: A bibliometric mapping of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, R. M., Deyerl, V. M., Hilger-Kolb, J., & Diehl, K. (2022). University fairness questionnaire (UFair): Development and validation of a German questionnaire to assess university justice—A study protocol of a mixed methods study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 16340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoebel, J., Maske, U. E., Zeeb, H., & Lampert, T. (2017). Social inequalities and depressive symptoms in adults: The role of objective and subjective socioeconomic status. PLoS ONE, 12, E0169764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hradil, S. (2009). Was prägt das krankheitsrisiko: Schicht, lage, lebensstil? In M. Richter, & K. Hurrelmann (Eds.), Gesundheitliche Ungleichheit: Grundlagen, probleme, perspektiven (pp. 35–54). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, H. P., Sifuentes, K. A., & Lilley, M. K. (2023). Context matters: Stress for minority students who attend minority-majority universities. Psychological Reports, 126, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamalumpundi, V., Silvers, S., Franklin, L., Neikirk, K., Spencer, E., Beasley, H. K., Wanajalla, C. N., Vue, Z., Crabtree, A., Kirabo, A., Gaddy, J. A., Damo, S. M., McReynolds, M. R., Odie, L. H., Murray, S. A., Zavala, M. E., Vazquez, A. D., & Hinton, A., Jr. (2024). Speaking up for the invisible minority: First-generation students in higher education. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 239, E31158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-B. (2022). Association between self-rated health, health promotion behaviors, and mental health factors among university students: Focusing on the health survey results in a university. The Journal of Korean Society for School & Community Health Education, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Strine, T. W., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 114, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroher, M., Beuße, M., Isleib, S., Becker, K., Ehrhardt, M.-C., Gerdes, F., Koopmann, J., Schommer, T., Schwabe, U., Steinkühler, J., Völk, D., Peter, F., & Buchholz, S. (2023). The student survey in Germany: 22nd social survey: The economic and social situation of students in Germany 2021. Available online: https://www.dzhw.eu/pdf/ab_20/Soz22_Exec_Summary_en.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Lampert, T., Kroll, L. E., Lippe, E. v. d., Müters, S., & Stolzenberg, H. (2013). Socioeconomic status and health. Epidemiologie und Gesundheitsberichterstattung. Robert Koch-Institut. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie, S. I., & Kim, H. S. (2024). The role of emotional similarity and emotional accuracy in belonging and stress among first-generation and continuing-generation students. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1355526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBouef, S., & Dworkin, J. (2021). First-generation college students and family support: A critical review of empirical research literature. Education Sciences, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Xie, Y., Sun, Z., Liu, D., Yin, H., & Shi, L. (2023). Factors associated with academic burnout and its prevalence among university students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 23, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac-Ginty, S., Lira, D., Lillo, I., Moraga, E., Cáceres, C., Araya, R., & Prina, M. (2024). Association Between socioeconomic position and depression, anxiety and eating disorders in university students: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 9, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). Maslach burnout inventory: Third edition. In Evaluating stress: A book of resources (pp. 191–218). Scarecrow Education. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, A., Rapsey, C., Sampson, N., Lee, S., Albor, Y., Al-Hadi, A. N., Alonso, J., Al-Saud, N., Altwaijri, Y., Andersson, C., Atwoli, L., Auerbach, R. P., Ayuya, C., Báez-Mansur, P. M., Ballester, L., Bantjes, J., Baumeister, H., Bendtsen, M., Benjet, C., … van der Heijde, C. (2025). Prevalence, age-of-onset, and course of mental disorders among 72,288 first-year university students from 18 countries in the World Mental Health International College Student (WMH-ICS) initiative. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 183, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurici-Pollock, D. E., Stallworth, R., & Khan, S. (2025). What we talk about when we talk about “first-generation students”: Exploring definitions in use on college and university websites. College & Research Libraries, 86, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L., Hoyt, L. T., Shane, J., & Storch, E. A. (2023). Associations between subjective social status and psychological well-being among college students. Journal of American College Health, 71, 2044–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, J. K., Lakhan, H. A., Sammartino, C. J., & Rosenthal, S. R. (2023). Depressive and anxiety symptoms in first generation college students. Journal of American College Health, 71, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plomin, R., & von Stumm, S. (2018). The new genetics of intelligence. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pössel, P., Wood, T., & Roane, S. J. (2022). Are negative views of the self, world and future, mediators of the relationship between subjective social status and depressive symptoms? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 50, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, T., Wei, P., & Zhu, C. (2024). Research on the influencing factors of subjective well-being of Chinese college students based on panel model. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1366765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, M., & Hurrelmann, K. (2006). Gesundheitliche ungleichheit: Ausgangsfragen und herausforderungen. In M. Richter, & K. Hurrelmann (Eds.), Gesundheitliche ungleichheit: Grundlagen, probleme, konzepte (pp. 11–31). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell, D. M., & Kimel, S. Y. (2025). A systematic review of first-generation college students’ mental health. Journal of American College Health, 73, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, L., Bau, A. M., Borde, T., Butler, J., Lampert, T., Neuhauser, H., Razum, O., & Weilandt, C. (2006). A basic set of indicators for mapping migrant status. Recommendations for epidemiological practice. Bundesgesundheitsblatt—Gesundheitsforschung—Gesundheitsschutz, 49, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendatzki, S., & Rathmann, K. (2022). Differences in students stress experiences and associations with health. Results of a path analysis. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung, 17, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sischka, P. E., Costa, A. P., Steffgen, G., & Schmidt, A. F. (2020). The WHO-5 well-being index—Validation based on item response theory and the analysis of measurement invariance across 35 countries. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 1, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E. B. K., Sagorac Gruichich, T., Maronge, J. M., Hoel, S., Victory, A., Stowe, Z. N., & Cochran, A. (2023). Mobile acceptance and commitment therapy with distressed first-generation college students: Microrandomized trial. JMIR Ment Health, 15, E43065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. (2024). The world health organization-five well-being index (WHO-5). Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/WHO-UCN-MSD-MHE-2024.01 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Williams-York, B., Guenther, G. A., Patterson, D. G., Mohammed, S. A., Kett, P. M., Dahal, A., & Frogner, B. K. (2024). Burnout, exhaustion, experiences of discrimination, and stress among underrepresented and first-generation college students in graduate health profession education. Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Journal, 104, Pzae095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worthen, M., Menchaca, J., & Laine, M. (2023). An intersectional approach to understanding the correlates of depression in college students: Discrimination, social status, and identity. Journal of American College Health, 71, 1220–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z. (2023). The association between social support provision, psychological capital, subjective well-being and sense of indebtedness among undergraduates with low socioeconomic status. BMC Psychology, 11, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S., & Hidayat, D. (2024). Family socioeconomic status influences academic burnout among college students: A systematic study. Bisma The Journal of Counseling, 8, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n | %/M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Gender | 1105 | |

| Female | 554 | 50.1 |

| Male | 551 | 49.9 |

| Age | 1089 | 25.51 (5.43) |

| Migration background | 1098 | |

| Yes | 206 | 18.8 |

| No | 892 | 81.2 |

| Additional socioeconomic characteristics | ||

| Primary source of income | 1069 | |

| Support from parents, relatives, partner | 371 | 34.7 |

| Funding of Federal Law on Support in Education | 183 | 17.1 |

| Own employment | 406 | 38.0 |

| Scholarship, Loans and Others | 109 | 10.2 |

| Living situation | 1088 | |

| Alone | 285 | 26.2 |

| With partner | 272 | 25.0 |

| In shared apartment | 206 | 18.9 |

| Student dormitory | 49 | 4.5 |

| With parents or relatives | 276 | 25.4 |

| Study-related characteristics | ||

| Type of University | 1105 | |

| University | 743 | 67.2 |

| University of applied sciences | 362 | 32.8 |

| Area of study | 1105 | |

| Humanities | 164 | 14.8 |

| Law, economics, and social sciences | 328 | 29.7 |

| Mathematics, natural sciences | 162 | 14.7 |

| Medicine, health sciences | 90 | 8.1 |

| Engineering | 176 | 15.9 |

| Art, art science | 29 | 2.6 |

| Sports | 24 | 2.2 |

| Others | 132 | 11.9 |

| Semester | 1086 | |

| 1–2 | 197 | 18.1 |

| 3–6 | 435 | 40.1 |

| >6 | 454 | 41.8 |

| SSS | Parental Academic Background | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 (n = 1105, M = 5.90, SD = 1.94) | No, Neither Parent (n = 555, 51.1%) | Yes, One Parent (n = 310, 28.5%) | Yes, Both Parents (n = 221, 20.3%) | |||||||

| Variables | n | M (SD)/r | p-Value | n | M (SD)/% | n | M (SD)/% | n | M (SD)/% | p-Value |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Gender | 1105 | 5.90 (1.94) | <0.001 | 555 | 100.0 | 310 | 100.0 | 221 | 100.0 | 0.001 |

| Female | 554 | 5.62 (1.90) | 305 | 55.0 x | 153 | 49.4 | 90 | 40.7 x | ||

| Male | 551 | 6.17 (1.94) | 250 | 45.0 x | 157 | 50.6 | 131 | 59.3 x | ||

| Age | 1089 | −0.057 | 0.021 | 552 | 25.67 (5.45) | 304 | 25.13 (5.63) | 220 | 25.70 (5.10) | 0.333 |

| Migration background | 1098 | 5.91 (1.93) | 0.553 | 553 | 100.0 | 310 | 100.0 | 221 | 100.0 | 0.170 |

| Yes | 206 | 5.84 (1.86) | 114 | 20.6 | 51 | 16.5 | 35 | 15.8 | ||

| No | 892 | 5.93 (1.95) | 439 | 79.4 | 259 | 83.5 | 186 | 84.2 | ||

| Additional socioeconomic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Primary source of income | 1069 | 5.90 (1.93) | 0.042 | 541 | 100.0 | 302 | 100.0 | 217 | 100.0 | <0.001 |

| Support from parents, relatives, partner | 371 | 6.01 a (1.88) | 159 | 29.4 x | 105 | 34.8 | 105 | 48.4 x | ||

| Funding of Federal Law on Support in Education | 183 | 5.51 a (2.07) | 105 | 19.4 | 54 | 17.9 | 23 | 10.6 x | ||

| Own employment | 406 | 5.96 (1.90) | 217 | 40.1 | 117 | 38.7 | 68 | 31.3 | ||

| Scholarship, Loans and Others | 109 | 5.97 (1.90) | 60 | 11.1 | 26 | 8.6 | 21 | 9.7 | ||

| Living situation | 1088 | 5.90 (1.93) | <0.001 | 552 | 100.0 | 307 | 100.0 | 218 | 100.0 | <0.001 |

| Alone | 285 | 6.02 a (1.90) | 155 | 28.1 | 70 | 22.8 | 58 | 26.6 | ||

| With partner | 272 | 6.19 b (1.99) | 127 | 23.0 | 81 | 26.4 | 63 | 28.9 | ||

| In shared apartment | 206 | 5.87 (1.92) | 94 | 17.0 | 57 | 18.6 | 52 | 23.9 | ||

| Student dormitory | 49 | 5.90 (2.07) | 17 | 3.1 | 17 | 5.5 | 14 | 6.4 | ||

| With parents or relatives | 276 | 5.51 ab (1.82) | 159 | 28.8 | 82 | 26.7 | 31 | 14.2 x | ||

| Study-related characteristics | ||||||||||

| Type of University | 1105 | 5.90 (1.94) | 0.612 | 555 | 100.0 | 310 | 100.0 | 221 | 100,0 | 0.028 |

| University | 743 | 5.88 (1.96) | 365 | 65.8 | 203 | 65.5 | 166 | 75.1 x | ||

| University of applied sciences | 362 | 5.94 (1.89) | 190 | 34.2 | 107 | 34.5 | 55 | 24.9 x | ||

| Area of study | 1105 | 5.90 (1.94) | 0.004 | 555 | 100.0 | 310 | 100.0 | 221 | 100.0 | 0.037 |

| Humanities | 164 | 5.56 a (1.99) | 87 | 15.7 | 48 | 15.5 | 29 | 13.1 | ||

| Law, economics, and social sciences | 328 | 5.92 (1.94) | 176 | 31.7 | 94 | 30.3 | 50 | 22.6 | ||

| Mathematics, natural sciences | 162 | 5.78 b (1.99) | 89 | 16.0 | 45 | 14.5 | 27 | 12.2 | ||

| Medicine, health sciences | 90 | 6.11 (2.09) | 35 | 6.3 | 23 | 7.4 | 31 | 14.0 x | ||

| Engineering | 176 | 6.03 (1.98) | 78 | 14.1 | 45 | 14.5 | 45 | 20.4 | ||

| Art, art science | 29 | 5.34 (2.11) | 17 | 3.1 | 7 | 2.3 | 5 | 2.3 | ||

| Sports | 24 | 6.75 ab (1.19) | 11 | 2.0 | 7 | 2.3 | 6 | 2.7 | ||

| Others | 132 | 6.04 (1.64) | 62 | 11.2 | 41 | 13.2 | 28 | 12.7 | ||

| Semester | 1086 | 5.90 (1.94) | <0.001 | 549 | 100.0 | 307 | 100.0 | 219 | 100.0 | 0.027 |

| 1–2 | 197 | 5.76 a (1.85) | 99 | 18.0 | 59 | 19.2 | 36 | 16.4 | ||

| 3–6 | 435 | 6.23 ab (1.92) | 195 | 35.5 x | 136 | 44.3 | 97 | 44.3 | ||

| >6 | 454 | 5.65 a (1.94) | 255 | 46.4 x | 112 | 36.5 | 86 | 39.3 | ||

| Model I | Model II | Model III | Model IV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | β | p-Value | β | p-Value | β | p-Value | β | p-Value |

| TOTAL SAMPLE | ||||||||

| Self-rated health | 0.322 | <0.001 | 0.291 | <0.001 | 0.319 | <0.001 | 0.311 | <0.001 |

| Well-being | 0.355 | <0.001 | 0.322 | <0.001 | 0.346 | <0.001 | 0.337 | <0.001 |

| Stress | −0.154 | <0.001 | −0.137 | <0.001 | −0.164 | <0.001 | −0.162 | <0.001 |

| Depression | −0.127 | <0.001 | −0.124 | <0.001 | −0.135 | <0.001 | −0.143 | <0.001 |

| Burnout | −0.219 | <0.001 | −0.255 | <0.001 | −0.223 | <0.001 | −0.234 | <0.001 |

| FEMALE STUDENTS | ||||||||

| Self-rated health | 0.300 | <0.001 | 0.296 | <0.001 | 0.286 | <0.001 | 0.279 | <0.001 |

| Well-being | 0.307 | <0.001 | 0.310 | <0.001 | 0.311 | <0.001 | 0.291 | <0.001 |

| Stress | −0.182 | <0.001 | −0.182 | <0.001 | −0.198 | <0.001 | −0.170 | <0.001 |

| Depression | −0.205 | <0.001 | −0.206 | <0.001 | −0.232 | <0.001 | −0.201 | <0.001 |

| Burnout | −0.278 | <0.001 | −0.285 | <0.001 | −0.289 | <0.001 | −0.263 | <0.001 |

| MALE STUDENTS | ||||||||

| Self-rated health | 0.309 | <0.001 | 0.290 | <0.001 | 0.311 | <0.001 | 0.304 | <0.001 |

| Well-being | 0.355 | <0.001 | 0.353 | <0.001 | 0.326 | <0.001 | 0.346 | <0.001 |

| Stress | −0.101 | 0.019 | −0.094 | 0.031 | −0.109 | 0.015 | −0.132 | 0.003 |

| Depression | −0.055 | 0.203 | −0.052 | 0.237 | −0.059 | 0.184 | −0.073 | 0.099 |

| Burnout | −0.156 | <0.001 | −0.148 | <0.001 | −0.151 | <0.001 | −0.191 | <0.001 |

| Model I | Model II | Model III | Model IV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | β | p-Value | β | p-Value | β | p-Value | β | p-Value |

| TOTAL SAMPLE | ||||||||

| Self-rated health | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | 0.114 | <0.001 | 0.101 | 0.001 | 0.114 | <0.001 | 0.100 | 0.002 |

| Yes, two parents | 0.162 | <0.001 | 0.136 | <0.001 | 0.170 | <0.001 | 0.158 | <0.001 |

| Well-being | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | 0.112 | <0.001 | 0.095 | 0.002 | 0.113 | <0.001 | 0.095 | 0.003 |

| Yes, two parents | 0.192 | <0.001 | 0.159 | <0.001 | 0.203 | <0.001 | 0.167 | <0.001 |

| Stress | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | −0.039 | 0.223 | −0.025 | 0.429 | −0.031 | 0.341 | −0.035 | 0.284 |

| Yes, two parents | −0.087 | 0.007 | −0.069 | 0.031 | −0.099 | 0.003 | −0.095 | 0.004 |

| Depression | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | 0.013 | 0.691 | 0.016 | 0.631 | 0.019 | 0.568 | 0.008 | 0.813 |

| Yes, two parents | −0.057 | 0.116 | −0.044 | 0.182 | −0.074 | 0.026 | −0.065 | 0.048 |

| Burnout | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | −0.010 | 0.761 | −0.009 | 0.774 | 0.003 | 0.928 | −0.013 | 0.679 |

| Yes, two parents | −0.099 | 0.002 | −0.096 | 0.003 | −0.109 | 0.001 | −0.104 | 0.001 |

| FEMALE STUDENTS | ||||||||

| Self-rated health | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | 0.035 | 0.432 | 0.039 | 0.384 | 0.033 | 0.468 | 0.027 | 0.540 |

| Yes, two parents | 0.109 | 0.014 | 0.106 | 0.018 | 0.105 | 0.027 | 0.115 | 0.010 |

| Well-being | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | 0.080 | 0.073 | 0.080 | 0.075 | 0.072 | 0.114 | 0.063 | 0.154 |

| Yes, two parents | 0.094 | 0.035 | 0.093 | 0.038 | 0.097 | 0.042 | 0.083 | 0.063 |

| Stress | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | −0.028 | 0.523 | −0.015 | 0.733 | −0.020 | 0.655 | −0.018 | 0.690 |

| Yes, two parents | −0.088 | 0.049 | −0.077 | 0.086 | −0.094 | 0.049 | −0.083 | 0.065 |

| Depression | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | 0.031 | 0.483 | 0.038 | 0.401 | 0.042 | 0.360 | 0.033 | 0.463 |

| Yes, two parents | −0.030 | 0.496 | −0.023 | 0.601 | −0.064 | 0.182 | −0.031 | 0.488 |

| Burnout | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | −0.006 | 0.886 | −0.007 | 0.869 | 0.016 | 0.726 | −0.002 | 0.969 |

| Yes, two parents | −0.083 | 0.061 | −0.085 | 0.057 | −0.092 | 0.055 | −0.076 | 0.091 |

| MALE STUDENTS | ||||||||

| Self-rated health | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | 0.189 | <0.001 | 0.178 | <0.001 | 0.189 | <0.001 | 0.179 | <0.001 |

| Yes, two parents | 0.188 | <0.001 | 0.179 | <0.001 | 0.195 | <0.001 | 0.183 | <0.001 |

| Well-being | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | 0.129 | 0.005 | 0.121 | 0.008 | 0.129 | 0.005 | 0.116 | 0.012 |

| Yes, two parents | 0.235 | <0.001 | 0.229 | <0.001 | 0.225 | <0.001 | 0.206 | <0.001 |

| Stress | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | −0.038 | 0.411 | −0.034 | 0.470 | −0.039 | 0.416 | −0.037 | 0.434 |

| Yes, two parents | −0.063 | 0.174 | −0.060 | 0.203 | −0.089 | 0.069 | −0.088 | 0.065 |

| Depression | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | −0.002 | 0.961 | −0.004 | 0.936 | −0.007 | 0.880 | −0.004 | 0.929 |

| Yes, two parents | −0.063 | 0.179 | −0.056 | 0.235 | −0.096 | 0.049 | −0.080 | 0.092 |

| Burnout | ||||||||

| No, neither parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes, one parent | −0.016 | 0.737 | −0.012 | 0.789 | −0.017 | 0.720 | −0.021 | 0.657 |

| Yes, two parents | −0.119 | 0.010 | −0.111 | 0.017 | −0.138 | 0.004 | −0.130 | 0.006 |

| Outcome | Self-Rated Health | Well-Being | Stress | Depression | Burnout | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variable | β | p-Value | β | p-Value | β | p-Value | β | p-Value | β | p-Value |

| SSS | ||||||||||

| SSS | 0.291 | <0.001 | 0.346 | <0.001 | −0.101 | 0.017 | −0.059 | 0.170 | −0.142 | <0.001 |

| Female students | −0.180 | <0.050 | −0.159 | 0.073 | 0.217 | 0.025 | 0.216 | 0.027 | 0.216 | 0.023 |

| SSS x female students | 0.034 | 0.711 | −0.082 | 0.354 | −0.133 | 0.170 | −0.219 | 0.026 | −0.264 | 0.006 |

| Parental academic background | ||||||||||

| One or two academic parents | 0.201 | <0.001 | 0.196 | <0.001 | −0.057 | 0.189 | −0.037 | 0.400 | −0.067 | 0.126 |

| Female students | −0.122 | 0.003 | −0.225 | <0.001 | 0.110 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.854 | −0.016 | 0.710 |

| One or two academic parents x female students | −0.100 | 0.044 | −0.083 | 0.086 | −0.005 | 0.918 | 0.036 | 0.484 | 0.014 | 0.783 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Södel, C.A.; Motzkau, M.; Wilfert, M.; Herr, R.M.; Diehl, K. Health Inequalities in German Higher Education: A Cross-Sectional Study Reveals Poorer Health in First-Generation University Students and University Students with Lower Subjective Social Status. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2026, 16, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16010011

Södel CA, Motzkau M, Wilfert M, Herr RM, Diehl K. Health Inequalities in German Higher Education: A Cross-Sectional Study Reveals Poorer Health in First-Generation University Students and University Students with Lower Subjective Social Status. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2026; 16(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleSödel, Corinna A., Marga Motzkau, Marcel Wilfert, Raphael M. Herr, and Katharina Diehl. 2026. "Health Inequalities in German Higher Education: A Cross-Sectional Study Reveals Poorer Health in First-Generation University Students and University Students with Lower Subjective Social Status" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 16, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16010011

APA StyleSödel, C. A., Motzkau, M., Wilfert, M., Herr, R. M., & Diehl, K. (2026). Health Inequalities in German Higher Education: A Cross-Sectional Study Reveals Poorer Health in First-Generation University Students and University Students with Lower Subjective Social Status. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 16(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16010011