Employment-Related Assistive Technology Needs in Autistic Adults: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Employment Challenges

1.2. Autism and Assistive Technology (AT)

1.3. Purposes

Research Question

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. AT Use

2.3.2. AT and AT Service Needs

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General AT Use

3.2. AT and AT Service Needs Assessment

3.3. Satisfaction with Current AT Use

3.3.1. Theme 1: Access to Support and Training

3.3.2. Theme 2: Accessibility and Availability of Technology

3.3.3. Theme 3: Impact on Communication and Independence

3.3.4. Theme 4: Match Between Needs and Technology

3.4. Discontinuation of AT Use

3.4.1. Theme 1: Issues Related to the AT

3.4.2. Theme 2: Growth and Desire for Independence

3.5. Additional Comments

3.5.1. Theme 1: Little to No Experience with AT

3.5.2. Theme 2: AT as a Game-Changer

3.5.3. Theme 3: Societal Misunderstanding of AT for Autistic Individuals

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adreon, D., & Durocher, J. S. (2007). Evaluating the college transition needs of individuals with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Intervention in School and Clinic, 42(5), 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agree, E. M., & Freedman, V. A. (2011). A quality-of-life scale for assistive technology: Results of a pilot study of aging and technology. Physical Therapy, 91(12), 1780–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K. L., Simon, A. R., Dempsey, J. R., Samaco, R. C., & Goin-Kochel, R. P. (2020). Evaluating two common strategies for research participant recruitment into autism studies: Observational study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e16752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K. D., Burke, R. V., Howard, M. R., Wallace, D. P., & Bowen, S. L. (2012). Use of audio cuing to expand employment opportunities for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(11), 2410–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, K. A., Roll, M. C., Malcolm, M. P., Taylor, A. A., & Graham, J. E. (2024). Assistive technology services for adults with disabilities in state-federal vocational rehabilitation programs. Disability and Rehabilitation Assistive Technology, 19(4), 1382–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders—Text revision (DSM-5-TR). In Psychopathology: Foundations for a contemporary understanding (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Chavarria, M. (2022). The autism predicament: Models of autism and their impact on autistic identity. Disability and Society, 37(8), 1321–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assistive Technology Act of 1998, Pub. L. No. 105-394, 112 Stat. 3627. (1998). Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/senate-bill/2432/text (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Bennett, K., Brady, M. P., Scott, J., Dukes, C., & Frain, M. (2010). The effects of covert audio coaching on the job performance of supported employees. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 25(3), 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, S., & Perry, J. (2013). Promoting independence through the use of assistive technology. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 18(4), 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M., Lee, D., Zhou, K., Iwanaga, K., Chan, F., & Tansey, T. (2022). Identifying vocational rehabilitation outreach and service training priorities: A national survey from diverse perspectives. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 56(3), 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bross, L. A., Travers, J. C., Wills, H. P., Huffman, J. M., Watson, E. K., Morningstar, M. E., & Boyd, B. A. (2020). Effects of video modeling for young adults with autism in community employment settings. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 43(4), 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, A. M., Vértes, P. E., Seidlitz, J., Kim, S. H., Grosenick, L., & Liston, C. (2023). Molecular and network-level mechanisms explaining individual differences in autism spectrum disorder. Nature Neuroscience, 26(4), 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahling, J. J., & Librizzi, U. A. (2015). Integrating the theory of work adjustment and attachment theory to predict job turnover intentions. Journal of Career Development, 42(3), 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Houting, J. (2019). Neurodiversity: An insider’s perspective. Autism, 23(2), 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, B. (2021). Autism and the right to a hypersensitivity-friendly workspace. Public Health Ethics, 14(3), 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vara, S., Guerrera, S., Menghini, D., Scibelli, F., Lupi, E., Valeri, G., & Vicari, S. (2024). Characterizing individual differences in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A descriptive study. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1323787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, B. D., Ewell, P. J., & Brauer, M. (2023). Data quality in online human-subjects research: Comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE, 18(3), e0279720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6 Pt 2), 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garçon, L., Khasnabis, C., Walker, L., Nakatani, Y., Lapitan, J., Borg, J., Ross, A., & Velazquez Berumen, A. (2016). Medical and assistive health technology: Meeting the needs of aging populations. The Gerontologist, 56(Suppl. S2), S293–S302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, T., Kriner, R., Sima, A., McDonough, J., & Wehman, P. (2015). Reducing the need for personal supports among workers with autism using an ipod touch as an assistive technology: Delayed randomized control trial. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 45(3), 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, A. J., Torres, R., Delgado, R., Hurley-Hanson, A. E., Giannantonio, C. M., Walrod, W., Maupin, Z., & Brady, J. (2024). Understanding unique employability skill sets of autistic individuals: A systematic review. Journal of Employment Counseling, 61(2), 74–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsen, C., Goe, R., & Bliss, S. (2019). Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) funding of job development and placement services: Implications for rural reach. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 51(3), 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klavina, A., Pérez-Fuster, P., Daems, J., Lyhne, C. N., Dervishi, E., Pajalic, Z., Øderud, T., Fuglerud, K. S., Markovska-Simoska, S., Przybyla, T., Klichowski, M., Stiglic, G., Laganovska, E., Alarcão, S. M., Tkaczyk, A. H., & Sousa, C. (2024). The use of assistive technology to promote practical skills in persons with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Digital Health, 10, 20552076241281260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klefbeck, K. (2023). Educational approaches to improve communication skills of learners with autism spectrum disorder and comorbid intellectual disability: An integrative systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 67(1), 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumazaki, H., Muramatsu, T., Yoshikawa, Y., Matsumoto, Y., Ishiguro, H., Kikuchi, M., Sumiyoshi, T., & Mimura, M. (2020). Optimal robot for intervention for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 74(11), 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenner, M. J., Warren, Z., Williams, A. R., Amoakohene, E., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Fitzgerald, R. T., Furnier, S. M., Hughes, M. M., Ladd-Acosta, C. M., McArthur, D., Pas, E. T., Salinas, A., Vehorn, A., Williams, S., Esler, A., Grzybowski, A., Hall-Lande, J., … Shaw, K. A. (2023). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 72(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C. M., Wilson, C. E., Robertson, D. M., Ecker, C., Daly, E. M., Hammond, N., Galanopoulos, A., Dud, I., Murphy, D. G., & McAlonan, G. M. (2016). Autism spectrum disorder in adults: Diagnosis, management, and health services development. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 1669–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbutt, N., Glaser, N., Francois, M. S., Schmidt, M., & Cobb, S. (2024). How are autistic people involved in the design of extended reality technologies? A systematic literature review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 54(11), 4232–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, D. B., & Klag, M. (2020). Critical reflections on employment among autistic adults. Autism in Adulthood: Challenges and Management, 2(4), 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics. (2021, February 10). Outcomes for disabled people in the UK: 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/articles/outcomesfordisabledpeopleintheuk/2021 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- O’Neill, S. J., Smyth, S., Smeaton, A., & O’Connor, N. E. (2020). Assistive technology: Understanding the needs and experiences of individuals with autism spectrum disorder and/or intellectual disability in Ireland and the UK. Assistive Technology: The Official Journal of RESNA, 32(5), 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palan, S., & Schitter, C. (2018). Prolific.ac—A subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 17, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., & Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, A., Stransky, M., Brucker, D., & Houtenville, A. (2019). The relationship between employment and health and health care among working-age adults with and without disabilities in the United States. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(19), 2299–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, A. M., Rast, J. E., Anderson, K. A., Garfield, T., & Shattuck, P. T. (2021). Vocational rehabilitation service utilization and employment outcomes among secondary students on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(1), 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, E., & Furnier, S. (2021). #Bias: The opportunities and challenges of surveys that recruit and collect data of autistic adults online. Autism in Adulthood, 3(2), 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, M. J. (2014). From people-centered to person-centered services, and back again. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 9(1), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlomer, G. L., Bauman, S., & Card, N. A. (2010). Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. J., Ginger, E. J., Wright, K., Wright, M. A., Taylor, J. L., Humm, L. B., Olsen, D. E., Bell, M. D., & Fleming, M. F. (2014). Virtual reality job interview training in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2450–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. J., Pinto, R. M., Dawalt, L., Smith, J. D., Sherwood, K., Miles, R., Taylor, J., Hume, K., Dawkins, T., Baker-Ericzén, M., Frazier, T., Humm, L., & Steacy, C. (2020). Using community-engaged methods to adapt virtual reality job-interview training for transition-age youth on the autism spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 71, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, C. (2020). Autism and employment: Implications for employers and adults with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(11), 4209–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, M. D., & Lindo, E. J. (2023). Executive functioning supports for college students with an autism spectrum disorder. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 10(4), 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansey, T. N., Bishop, M., Iwanaga, K., Zhou, K., & Chan, F. (2023). Vocational rehabilitation service delivery: Technical assistance needs of vocational rehabilitation professionals. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 58(1), 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkova, P., Sousa, C., Beiderbeck, D., Kochanowicz, A. M., Gerazov, B., Agius, M., Przybyła, T., Hoxha, M., & Tkaczyk, A. H. (2024). International perspectives on assistive technologies for autism and intellectual disabilities: Findings from a Delphi study. Disabilities, 4(4), 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. M., Engelsma, T., Taylor, J. O., Sharma, R. K., & Demiris, G. (2021). Recruiting older adult participants through crowdsourcing platforms: Mechanical Turk versus Prolific Academic. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, 2020, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Waisman-Nitzan, M., Gal, E., & Schreuer, N. (2019). Employers’ perspectives regarding reasonable accommodations for employees with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Management & Organization, 25(4), 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., & Jeon, M. (2024). Assistive technology for adults on the autism spectrum: A systematic survey. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 40(10), 2433–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widehammar, C., Lidström, H., & Hermansson, L. (2019). Environmental barriers to participation and facilitators for use of three types of assistive technology devices. Assistive Technology, 31(2), 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. J., Mitchell, J. M., Kemp, B. J., Adkins, R. H., & Mann, W. (2009). Effects of assistive technology on functional decline in people aging with a disability. Assistive Technology: The Official Journal of RESNA, 21(4), 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Research: Official Journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K., Richard, C., & Kim, J. (2025). Employment-related assistive technologies for autistic individuals: A scoping review. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 62, 10522263241312742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | n (%) | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 493 (98.4) | 34.07 (10.96) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 228 (45.5) | |

| Female | 194 (38.7) | |

| Non-binary | 52 (10.4) | |

| Transgender | 19 (3.8) | |

| Other (e.g., “Genderfluid”, “Agender”) | 6 (1.2) | |

| Prefer not to respond | 2 (0.4) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 330 (65.9) | |

| African American/Black | 64 (12.8) | |

| Multiracial | 61 (12.2) | |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 21 (4.2) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 16 (3.2) | |

| Native American/American Indian | 4 (0.8) | |

| Other (e.g., “Middle Eastern”, “Romani”) | 3 (0.6) | |

| Prefer not to respond | 2 (0.4) | |

| Other Disabilities | ||

| Yes | 284 (56.7) | |

| No | 215 (42.9) | |

| Did not respond | 2 (0.4) | |

| Age at diagnosis | 500 (99.8) | 18.75 (11.56) |

| Highest Educational Level | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 155 (30.9) | |

| Some college, no degree | 127 (25.3) | |

| Graduate or professional degree | 96 (19.2) | |

| High school graduate (or equivalency/GED) | 69 (13.8) | |

| Associate’s degree | 45 (9.0) | |

| Less than high school | 5 (1.0) | |

| Other (e.g., “Vocational, medical assistant”) | 4 (0.8) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time employed only | 236 (47.3) | |

| Unemployed | 76 (15.2) | |

| Part-time employed only | 69 (13.8) | |

| Self-employed only | 40 (8.0) | |

| Student only | 26 (5.2) | |

| Other (e.g., “disabled”, “homemaker”) | 24 (4.8) | |

| Student with employment | 23 (4.6) | |

| Retired | 5 (1.0) | |

| Did not respond | 2 (0.4) | |

| Primary Source of Financial Support | ||

| Self | 248 (49.5) | |

| Shared responsibility | 100 (20.0) | |

| Another family member | 86 (17.2) | |

| A spouse or partner | 38 (7.6) | |

| A professional agency (e.g., SSI, SSDI) | 18 (3.6) | |

| Other (e.g., “non-related roommates”) | 9 (1.8) | |

| Did not respond | 2 (0.4) |

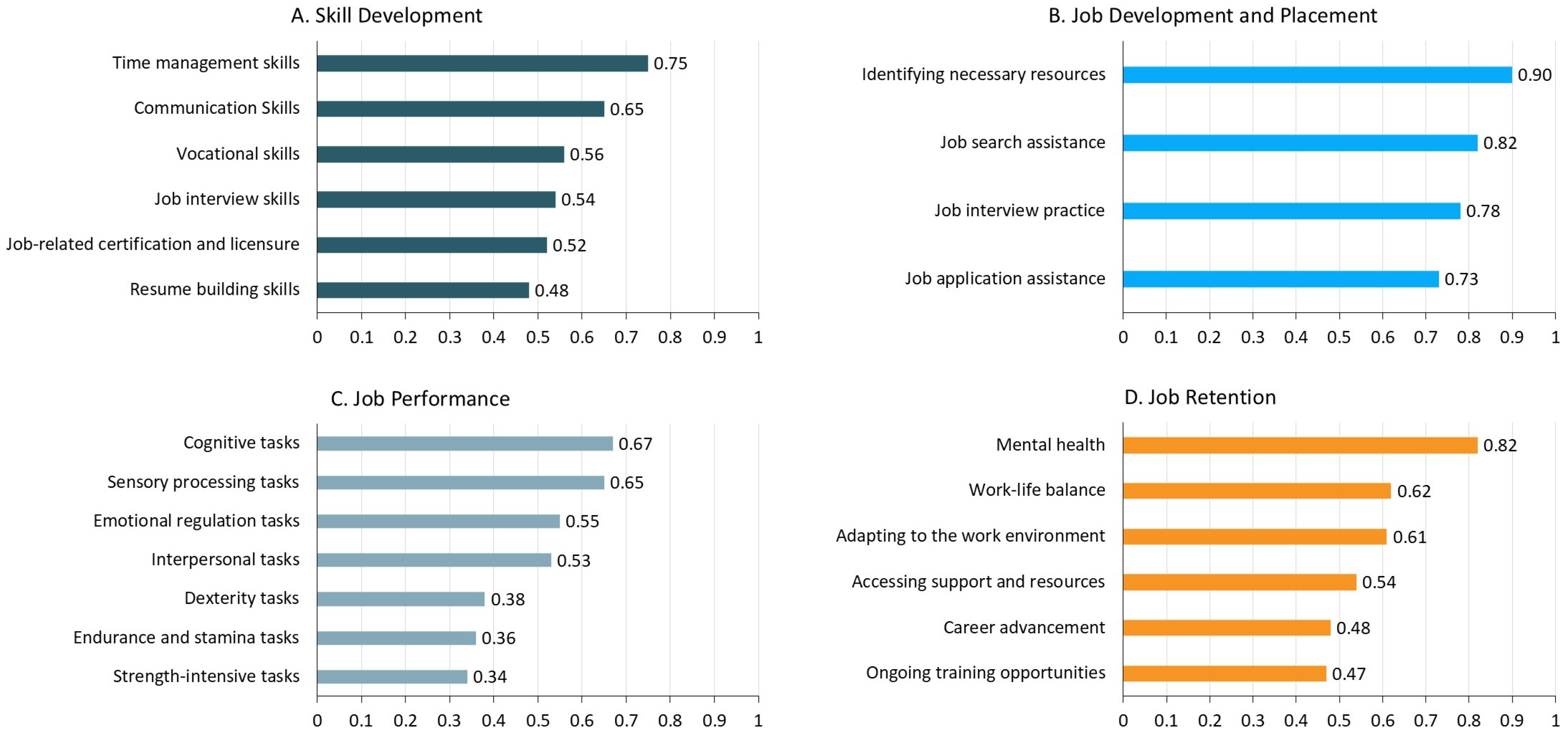

| Importance M (SD) | Relative Importance M (SD) | Needs M (SD) | Weighted Needs M (SD) | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Skill Development | |||||

| Time management skills | 3.66 (1.40) | 0.19 (0.07) | 3.49 (1.34) | 0.75 (0.45) | 1 |

| Communication Skills | 3.46 (1.46) | 0.18 (0.05) | 3.63 (1.29) | 0.65 (0.36) | 2 |

| Vocational skills | 3.21 (1.37) | 0.17 (0.05) | 3.33 (1.34) | 0.56 (0.29) | 3 |

| Job interview skills | 3.14 (1.46) | 0.16 (0.05) | 3.50 (1.35) | 0.54 (0.33) | 4 |

| Job-related certification and licensure | 3.07 (1.44) | 0.16 (0.05) | 3.32 (1.37) | 0.52 (0.33) | 5 |

| Resume building skills | 2.96 (1.41) | 0.15 (0.04) | 3.25 (1.35) | 0.48 (0.31) | 6 |

| Total needs | 3.51 (1.07) | ||||

| B. Job Development and Placement | |||||

| Identifying necessary resources | 3.24 (1.40) | 0.27 (0.07) | 3.53 (1.30) | 0.90 (0.51) | 1 |

| Job search assistance | 3.11 (1.47) | 0.25 (0.06) | 3.41 (1.36) | 0.82 (0.47) | 2 |

| Job interview practice | 3.03 (1.47) | 0.24 (0.06) | 3.45 (1.40) | 0.78 (0.47) | 3 |

| Job application assistance (e.g., navigating application portal, preparing application materials) | 2.94 (1.45) | 0.24 (0.05) | 3.32 (1.35) | 0.73 (0.44) | 4 |

| Total needs | 3.22 (1.29) | ||||

| C. Job Performance | |||||

| Cognitive tasks (e.g., memory and learning, planning, task management) | 3.67 (1.38) | 0.17 (0.06) | 3.53 (1.39) | 0.67 (0.41) | 1 |

| Sensory processing tasks (e.g., noise management, vision acuity) | 3.62 (1.45) | 0.17 (0.06) | 3.60 (1.35) | 0.65 (0.39) | 2 |

| Emotional regulation tasks (e.g., anger management, coping with change) | 3.36 (1.45) | 0.15 (0.04) | 3.48 (1.38) | 0.55 (0.33) | 3 |

| Interpersonal tasks (e.g., interacting with employers, co-workers, or customers) | 3.30 (1.40) | 0.15 (0.04) | 3.57 (1.38) | 0.53 (0.31) | 4 |

| Dexterity tasks (e.g., typing, using hand tools) | 2.75 (1.52) | 0.12 (0.04) | 2.95 (1.44) | 0.38 (0.28) | 5 |

| Endurance and stamina tasks (e.g., walking, standing) | 2.66 (1.49) | 0.12 (0.04) | 2.87 (1.44) | 0.36 (0.28) | 6 |

| Strength-intensive tasks (e.g., lifting, carrying) | 2.59 (1.49) | 0.12 (0.04) | 2.79 (1.46) | 0.34 (0.27) | 7 |

| Total needs | 3.48 (1.11) | ||||

| D. Job Retention | |||||

| Mental health | 3.87 (1.29) | 0.20 (0.07) | 3.84 (1.33) | 0.82 (0.41) | 1 |

| Work-life balance | 3.41 (1.41) | 0.20 (0.11) | 3.54 (1.33) | 0.62 (0.29) | 2 |

| Adapting to the work environment | 3.37 (1.41) | 0.17 (0.05) | 3.53 (1.33) | 0.61 (0.35) | 3 |

| Accessing support and resources | 3.17 (1.43) | 0.16 (0.04) | 3.58 (1.33) | 0.54 (0.31) | 4 |

| Career advancement (e.g., promotion, networking opportunities) | 3.01 (1.41) | 0.15 (0.04) | 3.42 (1.34) | 0.48 (0.29) | 5 |

| Ongoing training opportunities | 2.96 (1.42) | 0.15 (0.04) | 3.30 (1.34) | 0.47 (0.29) | 6 |

| Total needs | 3.53 (1.07) |

| Section/Theme | Frequency (n) | Description | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with Current AT Use | |||

| Theme 1: Access to Support and Training | 111 | Importance of professional support and training; lack of guidance leads to dissatisfaction. | “I need professional help to assess my needs for both my physical disabilities and Autism/ADHD. I have minimal tools currently.” |

| Theme 2: Accessibility and Availability of Technology | 49 | Barriers due to affordability, design, or access. | “The things I can find that I can afford are very minimally helpful or designed for people with profound support needs and no one in the middle.” |

| Theme 3: Impact on Communication and Independence | 114 | AT supports communication, independence, sensory regulation, and executive functioning. | “My smartwatch helps with reminders, Alexa assists with hands-free tasks, and ChatGPT offers quick information and support.” |

| Theme 4: Match Between Needs and Technology | 221 | Satisfaction depends on alignment between AT features and individual needs. | “What I use works well for me at the moment, but there are definitely other things that would probably help me out more.” |

| Not currently using AT | 41 | Reported no AT use at present. | — |

| Discontinuation of AT Use | |||

| Theme 1: Issues Related to the AT | 57 | AT abandoned due to poor usability, discomfort, or updates that reduced accessibility. | “I stopped using the technology because it became too cumbersome, and the updates made it less user-friendly for my needs.” |

| Theme 2: Growth and Desire for Independence | 42 | AT discontinued after skill development, personal growth, or desire for independence. | “It served its purpose for me… but now I feel empowered to manage my responsibilities independently.” |

| Additional Comments | |||

| Theme 1: Little to No Experience with AT | 58 | Many lacked exposure or knowledge of AT but expressed interest in learning more. | “I really didn’t consider using assistive technologies, but I realize now how helpful it could be in my daily life.” |

| Theme 2: AT as a Game-Changer | 51 | AT described as transformative for productivity, organization, and confidence. | “[Assistive technologies] have been a game-changer for me in the workplace. They’ve helped me stay organized, communicate more effectively, and manage tasks that would otherwise be challenging.” |

| Theme 3: Societal Misunderstanding of AT | 34 | Misunderstanding, stigma, or fear of disclosure discourage AT use. | “It hurts to be called ‘dramatic’ or a ‘faker’ because I am trying to work for a living.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, K.; Richard, C.; Zhai, Y.; Li, D.; Fry, H. Employment-Related Assistive Technology Needs in Autistic Adults: A Mixed-Methods Study. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090170

Zhou K, Richard C, Zhai Y, Li D, Fry H. Employment-Related Assistive Technology Needs in Autistic Adults: A Mixed-Methods Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(9):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090170

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Kaiqi, Constance Richard, Yusen Zhai, Dan Li, and Hannah Fry. 2025. "Employment-Related Assistive Technology Needs in Autistic Adults: A Mixed-Methods Study" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 9: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090170

APA StyleZhou, K., Richard, C., Zhai, Y., Li, D., & Fry, H. (2025). Employment-Related Assistive Technology Needs in Autistic Adults: A Mixed-Methods Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(9), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090170