Adaptation and Vulnerability in Chronic Pain: A Study of Profiles Based on Clinical and Psychological Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Materials

2.4. Data Analysis

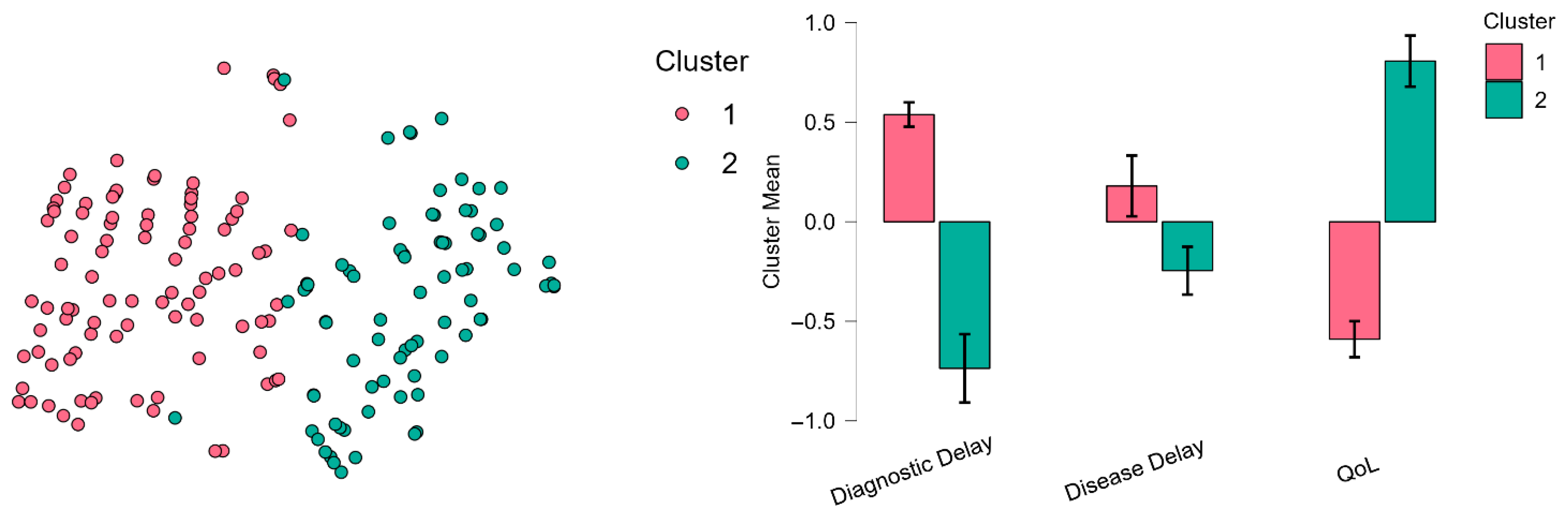

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almeida, V., Carvalho, C., & Pereira, M. (2020). The contribution of purpose in life to psychological morbidity and quality of life in chronic pain patients. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 25, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attali, D., Leguay, F., Milcent, L., & Baeza-Velasco, C. (2023). Association between activity pacing and negative emotions in patients with chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 39, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The helplessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boring, B. L., Maffly-Kipp, J., Mathur, V. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2022). Meaning in life and pain: The differential effects of coherence, purpose, and mattering on pain severity, frequency, and the development of chronic pain. Journal of Pain Research, 15, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breivik, H., Collett, B., Ventafridda, V., Cohen, R., & Gallacher, D. (2013). Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. European Journal of Pain, 10(4), 287–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A., Mathias, J., & Denson, L. (2020). Esperando servicios multidisciplinarios para el dolor crónico: Un estudio prospectivo de 2,5 años. Journal of Health Psychology, 25, 1198–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S., Vase, L., & Hooten, W. (2021). Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances. The Lancet, 397, 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dansie, E., & Turk, D. (2013). Assessment of patients with chronic pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 111(1), 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgin, E. (2024). How a ‘pain-o-meter’ could improve treatments. Nature, 633(8031), 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas, M., De Sola, H., Salazar, A., Esquivia, A., Rubio, S., & Failde, I. (2024). Prevalence and epidemiological characteristics of chronic pain in the Spanish population. Results from the pain barometer. European Journal of Pain, 29, e4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, H. W., & Law, L. F. (2024). Multisensory sensitivity in relation to pain: A scoping review of terminology and assessment. Pain Reports, 9(6), e1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R., Dworkin, R., Sullivan, M., Turk, D., & Wasan, A. (2016). The role of psychosocial processes in the development and maintenance of chronic pain. The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society, 17(9), 70–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erfani, T., Keefe, F., Bennell, K., Chen, J., Makovey, J., Metcalf, B., Williams, A. D., Zhang, Y., & Hunter, D. (2015). Psychological factors and pain exacerbation in knee osteoarthritis: A web based case-crossover study. Rheumatology: Current Research, S6(005), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahland, R., Kohlmann, T., Hasenbring, M., Feng, Y., & Schmidt, C. (2012). Which route leads from chronic back pain to depression? A path analysis on direct and indirect effects using the cognitive mediators catastrophizing and helplessness/hopelessness in a general population sample. Schmerz, 26(6), 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillingim, R. (2017). Individual differences in pain: Understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain, 158, S11–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P., Luyten, P., Moulton-Perkins, A., Lee, Y. W., Warren, F., Howard, S., Ghinai, R., Fearon, P., & Lowyck, B. (2016). Development and validation of a self-report measure of mentalizing: The reflective functioning questionnaire. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0158678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Alandete, J., Rosa, E., & Sellés, P. (2013). Estructura factorial y consistencia interna de una versión española del purpose-in-life test. Universitas Psychologica, 12(2), 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatchel, R., Neblett, R., Kishino, N., & Ray, C. (2016). Fear-avoidance beliefs and chronic pain. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 46(2), 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaesmer, H., Spangenberg, L., Scherer, A., & Forkmann, T. (2013). Assessing desire for suicide: First results on psychometric properties of the German version of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ). Psychiatrische Praxis, 41(5), 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M., Horjales-Araujo, E., & Dahl, J. (2015). Associations between psychological variables and pain in experimental pain models. A systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 59, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervás, G., & Jódar, R. (2008). Adaptación al castellano de la escala de dificultades en la regulación emocional. Clínica y Salud, 19(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer, K., Todorovic, M., Wilson, E., Steinberg, A., Avidan, M., & Haroutounian, S. (2024). Cognitive flexibility training for chronic pain: A randomized clinical study. Pain Reports, 9, e1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, T. E., Ribeiro, J. D., & Silva, C. (2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal behavior, and their co-occurrence as viewed through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kak, A., Batra, M., Erbas, B., Sadler, S., Chuter, V., Jenkins, J., Ozcan, H., Lafferty, D., Amir, O., & Cotchett, M. (2025). Psychological factors associated with pain and function in adults with hallux valgus. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research, 18(1), e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamper, S. J., Apeldoorn, A. T., Chiarotto, A., Smeets, R. J. E. M., Ostelo, R. W. J. G., Guzman, J., & van Tulder, M. W. (2015). Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(9), CD000963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, J., Wilson, K., McWilliams, L., Péloquin, K., & Duong, D. (2012). Self-perceived burden in chronic pain: Relevance, prevalence, and predictors. Pain, 153, 1735–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristofferzon, M., Engström, M., & Nilsson, A. (2018). Coping mediates the relationship between sense of coherence and mental quality of life in patients with chronic illness: A cross-sectional study. Quality of Life Research, 27, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, P., Hernández, C., Ferrí, C., Hidalgo, R., & López, L. (2011). Pain, health related quality of life and healthcare resource utilization in Spain. Journal of Medical Economics, 14, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality, 1, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, S., Rudich, Z., Brill, S., Shalev, H., & Shahar, G. (2015). Longitudinal associations between depression, anxiety, pain, and pain-related disability in chronic pain patients. Psychosomatic Medicine, 77, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddy, C., Poulin, P., Hunter, Z., Smyth, C., & Keely, E. (2017). Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 17, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S. J., & Shaw, W. S. (2011). Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain. Physical Therapy, 91(5), 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lötsch, J., Alfredsson, L., & Lampa, J. (2019). Machine-learning based knowledge discovery in rheumatoid arthritis related registry data to identify predictors of persistent pain. Pain, 161, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M., Campbell, F., Clark, A., Dunbar, M., Goldstein, D., Peng, P., Stinson, J., & Tupper, H. (2008). A systematic review of the effect of waiting for treatment for chronic pain. Pain, 136, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, L., & Samuel, V. (2007). The role of avoidance, pacing, and other activity patterns in chronic pain. Pain, 130, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, K., & Gross, J. (2020). Emotion regulation. Emotion, 20(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulders, A. (2019). From fear of movement-related pain and avoidance to chronic pain disability: A state-of-the-art review. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 26, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M., & Cao, R. (2024). Mutually beneficial relationship between meaning in life and resilience. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 58, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molton, I. R., Stoelb, B. L., Jensen, M. P., Ehde, D. M., Raichle, K. A., & Cardenas, D. D. (2009). Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in spinal cord injury: Replication and cross-validation. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 46(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Cuadrado, F., Barrero-Santiago, L., & Santos-Bermejo, M. (2025). Pain revolution in the public health system: Active coping strategies for chronic pain unit. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 29(2), 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman-Nott, N., Hesam-Shariati, N., Wewege, M., Rizzo, R., Cashin, A., Wilks, C., Quidé, Y., McAuley, J., & Gustin, S. (2024). Emotion regulation skills-focused interventions for chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Pain, 28, 1276–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M., Carvalho, C., Costa, E., Leite, Â., & Almeida, V. (2020). Quality of life in chronic pain patients: Illness- and wellness-focused coping as moderators. PsyCh Journal, 10, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, M., & Lucchetti, G. (2010). Coping strategies in chronic pain. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 14, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, P., & Ingvar, M. (2002). Imaging cognitive modulation of pain processing. Pain, 95, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, H. (1987). Avoidance behaviour and its role in sustaining chronic pain. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 25(4), 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, D., Day, M., Ferreira-Valente, A., & Jensen, M. (2024). Belief in living a meaningful life and adjustment to chronic pain. Pain Medicine, 26, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, M., Eccleston, C., & Pillemer, K. (2015). Management of chronic pain in older adults. The BMJ, 350, h532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C. J., Carpenter, R. W., & Tragesser, S. L. (2018). Accounting for the association between BPD features and chronic pain complaints in a pain patient sample: The role of emotion dysregulation factors. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 9(3), 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Parra, E., Manzano-García, G., Mediavilla, R., Rodríguez-Vega, B., Lahera, G., Moreno-Pérez, A. I., Torres-Cantero, A. M., Rodado-Martínez, J., Bilbao, A., & González-Torres, M. Á. (2023). The Spanish version of the reflective functioning questionnaire: Validity data in the general population and individuals with personality disorders. PLoS ONE, 18(4), e0274378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Teruel, D., Robles-Bello, M. A., & Camacho-Conde, J. A. (2020). Validez de la versión española del Herth Hope Index y la Beck Hopelessness Scale en personas que han realizado una tentativa de suicidio. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría, 48(4), 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Scheidegger, A., Jäger, J., Blättler, L., Aybek, S., Bischoff, N., & Holtforth, G. (2023). Identification and characterization of pain processing patterns among patients with chronic primary pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 39, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semple, T., & Hogg, M. (2012). Waiting in pain. The Medical Journal of Australia, 196, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sil, S., Manikowski, A., Schneider, M., Cohen, L., & Dampier, C. (2021). An empirical classification of chronic pain subgroups in pediatric sickle cell disease: A cluster-analytic approach. Blood, 138, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S., Pushpa, P., & Peter, R. (2024). Anxiety and Depression among patients with chronic pain. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 24, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J., & Monsalve, V. (2017). CAD-R. Cuestionario de afrontamiento al dolor crónico: Análisis factorial confirmatorio. ¿Hay diferencias individuales en sexo, edad y tipo de dolor? Revista de la Sociedad Española del Dolor, 24(5), 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, R., Chibnall, J., & Kalauokalani, D. (2021). Patient perceptions of physician burden in the treatment of chronic pain. The Journal of Pain, 22, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburin, S., Magrinelli, F., & Zanette, G. (2014). Diagnostic and therapeutic pitfalls in considering chronic pain as a disease. Pain Medicine, 15(9), 1640–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, L., De Oliveira Vidal, E., Blake, H., De Barros, G., & Fukushima, F. (2023). Evaluating the interaction between pain intensity and resilience on the impact of pain in the lives of people with fibromyalgia. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 40, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treede, R., Rief, W., Barke, A., Aziz, Q., Bennett, M., Benoliel, R., Cohen, M., Evers, S., Finnerup, N., First, M., Giamberardino, M., Kaasa, S., Korwisi, B., Kosek, E., Lavand’homme, P., Nicholas, M., Perrot, S., Scholz, J., Schug, S., … Wang, S. (2019). Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP classification of chronic pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain, 160, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, D. C., & Rudy, T. E. (1988). Toward an empirically derived taxonomy of chronic pain patients: Integration of psychological assessment data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(2), 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Orden, K. A., Cukrowicz, K. C., Witte, T. K., & Joiner, T. E. (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the interpersonal needs questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ryckeghem, D., Van Damme, S., Eccleston, C., & Crombez, G. (2018). The efficacy of attentional distraction and sensory monitoring in chronic pain patients: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volders, S., Boddez, Y., De Peuter, S., Meulders, A., & Vlaeyen, J. (2015). Avoidance behavior in chronic pain research: A cold case revisited. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 64, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Xu, J., Ma, Z., Jia, C., Wang, G., & Zhou, L. (2020). The mediating role of depressive symptoms, hopelessness, and perceived burden on the association between pain intensity and late-life suicide in rural China: A case–control psychological autopsy study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 779178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiech, K. (2016). Deconstructing the sensation of pain: The influence of cognitive processes on pain perception. Science, 354, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K., Kowal, J., Caird, S., Castillo, D., McWilliams, L., & Heenan, A. (2017). Self-perceived burden, perceived burdensomeness, and suicidal ideation in patients with chronic pain. Canadian Journal of Pain, 1, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | N | Mean | SD | SE | CV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIL-Sense of Life | 1 | 145 | 21.566 | 7.356 | 0.611 | 0.341 |

| 2 | 106 | 27.698 | 8.101 | 0.787 | 0.292 | |

| PIL-Propose | 1 | 145 | 18.476 | 5.171 | 0.429 | 0.280 |

| 2 | 106 | 20.981 | 5.368 | 0.521 | 0.256 | |

| RFQ8—Uncertainty | 1 | 145 | 0.840 | 0.745 | 0.062 | 0.887 |

| 2 | 106 | 0.575 | 0.533 | 0.052 | 0.926 | |

| RFQ8—Certainty | 1 | 145 | 0.867 | 0.804 | 0.067 | 0.928 |

| 2 | 106 | 1.006 | 0.720 | 0.070 | 0.715 | |

| Perceived Burdensomeness | 1 | 145 | 21.041 | 10.776 | 0.895 | 0.512 |

| 2 | 106 | 13.349 | 8.799 | 0.855 | 0.659 | |

| Frustrated Belongingness | 1 | 145 | 41.683 | 7.656 | 0.636 | 0.184 |

| 2 | 106 | 40.368 | 6.502 | 0.632 | 0.161 | |

| BHS—Hopelessness | 1 | 145 | 10.641 | 5.279 | 0.438 | 0.496 |

| 2 | 106 | 6.934 | 5.229 | 0.508 | 0.754 | |

| DERS—Dysregulation | 1 | 145 | 86.648 | 20.015 | 1.662 | 0.231 |

| 2 | 106 | 72.792 | 21.953 | 2.132 | 0.302 | |

| Prayer | 1 | 145 | 12.448 | 7.027 | 0.584 | 0.564 |

| 2 | 106 | 11.453 | 6.638 | 0.645 | 0.580 | |

| Catharsis | 1 | 145 | 12.510 | 4.981 | 0.414 | 0.398 |

| 2 | 106 | 11.792 | 4.724 | 0.459 | 0.401 | |

| Distraction | 1 | 144 | 17.611 | 5.625 | 0.469 | 0.319 |

| 2 | 105 | 17.438 | 6.256 | 0.610 | 0.359 | |

| Mental Control | 1 | 145 | 12.724 | 5.320 | 0.442 | 0.418 |

| 2 | 106 | 11.075 | 5.343 | 0.519 | 0.482 | |

| Self-Affirmation | 1 | 145 | 17.800 | 4.638 | 0.385 | 0.261 |

| 2 | 106 | 17.953 | 5.298 | 0.515 | 0.295 | |

| Information Seeking | 1 | 145 | 19.076 | 4.637 | 0.385 | 0.243 |

| 2 | 106 | 16.915 | 5.011 | 0.487 | 0.296 |

| 95% CI for Cohen’s d | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | df | p | Cohen’s d | SE Cohen’s d | Lower | Upper | |

| PIL-Sense of Life | −6.250 | 249 | <0.001 | −0.799 | 0.136 | −1.058 | −0.538 |

| PIL-Propose | −3.731 | 249 | <0.001 | −0.477 | 0.131 | −0.730 | −0.222 |

| RFQ8—Uncertainty | 3.120 | 249 | 0.002 | 0.399 | 0.130 | 0.145 | 0.651 |

| RFQ8—Certainty | −1.420 | 249 | 0.157 | −0.181 | 0.128 | −0.432 | 0.070 |

| Perceived Burdensomeness | 6.025 | 249 | <0.001 | 0.770 | 0.136 | 0.510 | 1.029 |

| Frustrated Belongingness | 1.431 | 249 | 0.154 | 0.183 | 0.128 | −0.068 | 0.434 |

| BHS—Hopelessness | 5.518 | 249 | <0.001 | 0.705 | 0.134 | 0.446 | 0.962 |

| DERS—Dysregulation | 5.199 | 249 | <0.001 | 0.664 | 0.134 | 0.407 | 0.921 |

| Prayer | 1.135 | 249 | 0.258 | 0.145 | 0.128 | −0.106 | 0.396 |

| Catharsis | 1.153 | 249 | 0.250 | 0.147 | 0.128 | −0.104 | 0.398 |

| Distraction | 0.229 | 247 | 0.819 | 0.029 | 0.128 | −0.222 | 0.281 |

| Mental Control | 2.421 | 249 | 0.016 | 0.309 | 0.129 | 0.057 | 0.561 |

| Self-Affirmation | −0.243 | 249 | 0.808 | -0.031 | 0.128 | −0.281 | 0.219 |

| Information Seeking | 3.524 | 249 | <0.001 | 0.450 | 0.130 | 0.196 | 0.703 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mora-Ascó, J.J.; Moret-Tatay, C.; Jorques-Infante, M.J.; Beneyto-Arrojo, M.J. Adaptation and Vulnerability in Chronic Pain: A Study of Profiles Based on Clinical and Psychological Factors. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090168

Mora-Ascó JJ, Moret-Tatay C, Jorques-Infante MJ, Beneyto-Arrojo MJ. Adaptation and Vulnerability in Chronic Pain: A Study of Profiles Based on Clinical and Psychological Factors. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(9):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090168

Chicago/Turabian StyleMora-Ascó, Juan José, Carmen Moret-Tatay, María José Jorques-Infante, and María José Beneyto-Arrojo. 2025. "Adaptation and Vulnerability in Chronic Pain: A Study of Profiles Based on Clinical and Psychological Factors" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 9: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090168

APA StyleMora-Ascó, J. J., Moret-Tatay, C., Jorques-Infante, M. J., & Beneyto-Arrojo, M. J. (2025). Adaptation and Vulnerability in Chronic Pain: A Study of Profiles Based on Clinical and Psychological Factors. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(9), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090168