The Spirituality–Resilience–Happiness Triad: A High-Powered Model for Understanding University Student Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Review of Spirituality, Resilience, and Happiness in Higher Education Students: Findings, Challenges, and Opportunities in Educational Psychology

2.2. Spirituality Influences Happiness in Higher Education Students

2.3. Resilience as a Determinant of Happiness in Higher Education Students

2.4. Spirituality Influences the Resilience of Higher Education Students

2.5. The Mediating Role of Religious Belief and Years of Study in Higher Education

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

- Stage 1: Data preparation and descriptive analysis. Data cleaning was conducted using Microsoft Excel, followed by comprehensive descriptive analyses. Missing data patterns were evaluated systematically. Outliers were identified using standardized z-scores (|z| > 3.29) and visual inspection of boxplots, with six cases removed due to extreme values across multiple variables.

- Stage 2: Measurement model validation. Confirmatory factor analysis assessed convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was evaluated through factor loadings (threshold ≥ 0.70) and average variance extracted (AVE, threshold ≥ 0.50), following the recommendations of Hair et al. (2017). Items HAP5 and RES10 were removed due to insufficient factor loadings (<0.70), ensuring measurement model adherence to established psychometric criteria.

- Stage 3: Reliability assessment. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (α), composite reliability (CR), and rho_a coefficients, all exceeding the 0.70 threshold established by Hair et al. (2019).

- Stage 4: Discriminant validity testing. Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion and heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratios, with values below 0.85 indicating adequate discriminant validity (Ringle et al., 2023).

- Stage 5: Structural model testing. Hypotheses were tested using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS v.4.0. PLS-SEM was selected over covariance-based SEM due to its appropriateness for predictive modeling, accommodation of smaller sample sizes, and flexibility with complex models including interaction effects. The structural model included direct effects (spirituality → happiness, resilience → happiness, spirituality → resilience) and moderating effects of religious belief and years of study.

- Stage 6: Model evaluation. Model quality was assessed through coefficient of determination (R2), predictive relevance (Q2) using blindfolding procedures, effect sizes (f2), and model fit indices including standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df), and normed fit index (NFI).

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Measurement Model

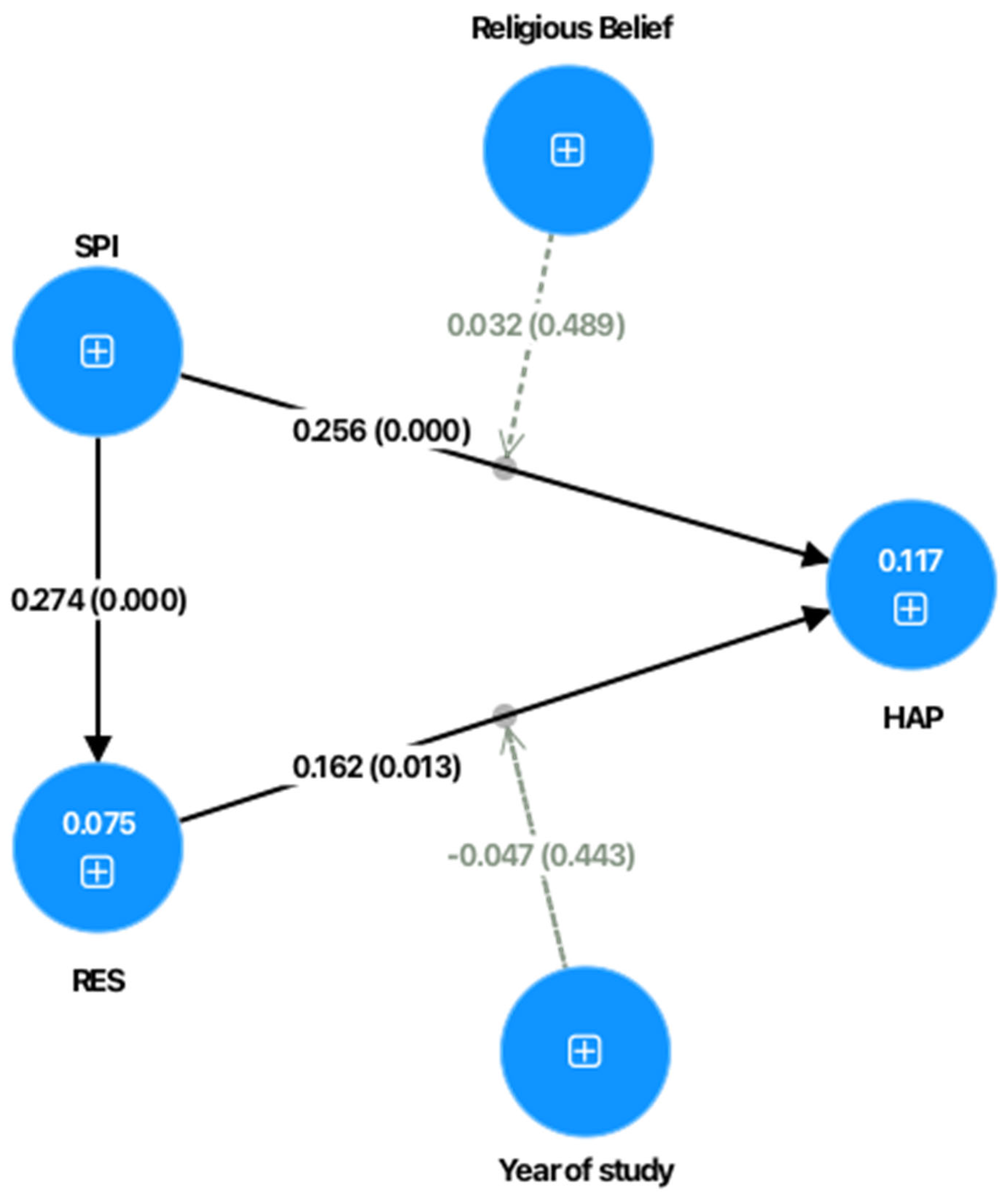

4.2. Testing the Research Hypotheses

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abulfaraj, G. G., Upsher, R., Zavos, H. M. S., & Dommett, E. J. (2024). The impact of resilience interventions on university students’ mental health and well-being: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 14(5), 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, B. G. A., Ballesteros, M. A. A., Ninaquispe, J. C. M., Farroñán, E. V. R., Tirado, K. S., Jordan, O. H., Ulloa, C. R. G., & Valle, M. d. l. Á. G. (2024). Evaluation of the determining factors of the intention to use, satisfaction and recommendation of mobile wallets adapted to the Utaut2 model in the Peruvian context. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 13(1), 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Enriquez, B. G., Arbulú Ballesteros, M. A., Huamaní Jordan, O., López Roca, C., & Saavedra Tirado, K. (2024). Analysis of college students’ attitudes toward the use of ChatGPT in their academic activities: Effect of intent to use, verification of information and responsible use. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Omari, O., Al Yahyaei, A., Wynaden, D., Damra, J., Aljezawi, M., Al Qaderi, M., Al Ruqaishi, H., Abu Shahrour, L., & ALBashtawy, M. (2023). Correlates of resilience among university students in Oman: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, V., Jones, J., & Gill, P. S. (2015). The relationship between spirituality, health and life satisfaction of undergraduate students in the UK: An online questionnaire study. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(1), 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, S., Mishra, G., Kankane, N., Khetan, J., Mahajan, N., Patel, A., & Chhabra, K. G. (2024). Link between individual resilience and aggressiveness in dental students and the mediating effect of spirituality: A path analysis. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 13(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbayannis, G., Bandari, M., Zheng, X., Baquerizo, H., Pecor, K. W., & Ming, X. (2022). Academic stress and mental well-being in college students: Correlations, affected groups, and COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 886344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaola Ugarte, A. D., Garcia Garcia, M., Martinez Campos, N., Ocampos Madrid, M., Livia, J., Bernaola Ugarte, A. D., Garcia Garcia, M., Martinez Campos, N., Ocampos Madrid, M., & Livia, J. (2022). Validez y confiabilidad de la escala breve de resiliencia connor-davidson (CD-RISC 10) en estudiantes universitarios de Lima Metropolitana. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(1), e-2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M. L., Lane, M., Carter, A., Barnard, S., & Ibrahim, O. (2019a). Evaluation of a leadership development program to enhance university staff and student resilience. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 10(2), 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M. L., van Kessel, G., Sanderson, B., Naumann, F., Lane, M., Reubenson, A., & Carter, A. (2019b). Resilience in higher education students: A scoping review. Higher Education Research and Development, 38(6), 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, A. N., & Astin, H. S. (2008). The correlates of spiritual struggle during the college years. Journal of Higher Education, 79(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhori, B., Hassan, Z., Hadjar, I., & Hidayah, R. (2017). The effect of sprituality and social support from the family toward final semester university students’ resilience. Man in India, 97(19), 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Carranza Esteban, R. F., Turpo-Chaparro, J. E., Mamani-Benito, O., Torres, J. H., & Arenaza, F. S. (2021). Spirituality and religiousness as predictors of life satisfaction among Peruvian citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon, 7(5), e06939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Bian, F., & Zhu, Y. (2023). The relationship between social support and academic engagement among university students: The chain mediating effects of life satisfaction and academic motivation. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codato, M., Shaver, P. R., Testoni, I., & Ronconi, L. (2011). Civic and moral disengagement, weak personal beliefs and unhappiness: A survey study of the «famiglia lunga» phenomenon in Italy. TPM—Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 18(2), 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z., Lin, Z., Ren, J., Cao, Y., & Tian, X. (2024). Exploring self-esteem and personality traits as predictors of mental wellbeing among Chinese university students: The mediating and moderating role of resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1308863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, R., Singh, S., Ribeiro, N., & Gomes, D. R. (2022). Does spirituality influence happiness and academic performance? Religions, 13(7), 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duche-Pérez, A. B., Vera-Revilla, C. Y., Gutiérrez-Aguilar, O. A., Chicana-Huanca, S., & Chicana-Huanca, B. (2024). Religion and spirituality in university students: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Society, 14(4), 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. D. (2010). Spirituality, religion, and work values. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 38(1), 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durso, S. O., Afonso, L. E., & Beltman, S. (2021). Resilience in higher education: A conceptual model and its empirical analysis. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 29, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwonye, A. U., Sheikhomar, N., & Phung, V. (2020). Spirituality: A psychological resource for managing academic-related stressors. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 23(9), 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo Portillo, M. T., Hernández Gómez, J. A., Estebané Ortega, V., & Martínez Moreno, G. (2016). Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales: Características, fases, construcción, aplicación y resultados. Ciencia & Trabajo, 18(55), 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etherton, K., Steele-Johnson, D., Salvano, K., & Kovacs, N. (2022). Resilience effects on student performance and well-being: The role of self-efficacy, self-set goals, and anxiety. Journal of General Psychology, 149(3), 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhi, F., Jeljeli, R., Aburezeq, I., Dweikat, F. F., Al-shami, S. A., & Slamene, R. (2023). Analyzing the students’ views, concerns, and perceived ethics about chat GPT usage. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, A. (2024). Students in higher education explore the practice of gratitude as spirituality and its impact on well-being. Religions, 15(9), 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, J. (2022). Model fit—CFA. Available online: https://statwiki.gaskination.com/index.php?title=CFA#Model_Fit (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Gilbertson, M. K., Brady, S. T., Ablorh, T., Logel, C., & Schnitker, S. A. (2022). Closeness to God, spiritual struggles, and wellbeing in the first year of college. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 742265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rivera, J. A., Veray-Alicea, J., & Rosario-Rodríguez, A. (2017). Desarrollo, validación y descripción teórica de la escala de espiritualidad personal en una muestra de adultos en Puerto Rico. Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicologia, 28(2), 388–404. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild, T., Heath, G., & Richardson, A. (2023). Delivering resilience: Embedding a resilience building module into first-year curriculum. Student Success, 14(2), 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J. B. (2023). How faith can be used to help black college students navigate higher education. In Successful pathways for the well-being of black students (pp. 189–200). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güldaş, F. Z., & Karslı, F. (2023). Exploring the moderating effect of spiritual resilience on the relationship between psychological resilience and mental health. Spiritual Psychology and Counseling, 8(3), 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F. (2009). Multivariate data analysis. Faculty Articles. Available online: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/facpubs/2925 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C., & Gudergan, S. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hatami, S., & Shekarchizadeh, H. (2022). Relationship between spiritual health, resilience, and happiness among a group of dental students: A cross-sectional study with structural equation modeling method. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayati, F., Mahboubi, M., Zahedi, A., Mehr, B. R., & Mohammadi, M. (2016). A study of the relationship between daily spiritual experiences and happiness in students at Abadan school of medical sciences. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, 11(11), 1248–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Sampieri, R., & Mendoza Torres, C. P. (2018). Metodología de la investigación: Las rutas: Cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta. Mc Graw Hill Educación. Available online: https://centrohumanista.edu.mx/biblioteca/files/original/5121ad6aa80b501a60abcb26790c7762.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Howard, A. H., Roberts, M., Mitchell, T., & Wilke, N. G. (2023). The relationship between spirituality and resilience and well-being: A study of 529 care leavers from 11 nations. Adversity and Resilience Science, 4(2), 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huamani Gomez, V. Y., & Mendoza Mori, G. M. (2022). Escala de felicidad subjetiva (SHS): Adaptación, evidencias psicométricas y datos normativos en adultos de Lima metropolitana. Repositorio Institucional—UCV. Available online: https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/100017 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Jalilian, N., Ziapour, A., Mokari, Z., & Kianipour, N. (2017). A study of the relationship between the components of spiritual health and happiness of students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences in 2016. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 10(4), 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, K. B. (2015). Intelligent systems for human resources. Aviation Space and Environmental Medicine, 59(Suppl. 11), a65–a68. [Google Scholar]

- Kneipp, L. B., Cyphers, B., & Kelly, K. E. (2009). Feeling at peace with college: Religiosity, spiritual well-being, and college adjustment. Individual Differences Research, 7(3), 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, B. C. H., Arnold, R., & Rodriguez-Rubio, B. (2014). Mediating effects of coping in the link between spirituality and psychological distress in a culturally diverse undergraduate sample. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 17(2), 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y. K., Snodgrass, J. L., Fenzel, L. M., & Tran, T. V. (2021). Acculturative stress and coping processes among middle-aged Vietnamese-born American Catholics: The roles of spirituality, religiosity, and resilience on well-being. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 12(2), 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. S., & Waters, C. (2013). Impact of stressful life experiences and of spiritual well-being on trauma symptoms. In Traumatic stress and its aftermath: Cultural, community, and professional contexts (pp. 39–47). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C. H., & Pong, H. K. (2021). Cross-sectional study of the relationship between the spiritual wellbeing and psychological health among university students. PLoS ONE, 16(4), e0249702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J., & Zhan, M. (2024). The influence of university management strategies and student resilience on students well-being & psychological distress: Investigating coping mechanisms and autonomy as mediators and parental support as a moderator. Current Psychology, 43(31), 25604–25620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Aguilar, D., Álvarez-Pérez, P. R., González-Ramos, J. A., & Garcés-Delgado, Y. (2023). The development of resilient behaviors in the fight against university academic dropout. Educacion XX1, 26(2), 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, C., & Nordstokke, D. (2023). Mindful self-care and resilience in first-year undergraduate students. Journal of American College Health, 71(8), 2569–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowreader, A. (2024). Fostering college student spiritual wellness on campus. Higher Education Review, 27(8), 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, E., & Sgoutas-Emch, S. (2007). The relationship between spirituality, health beliefs, and health behaviors in college students. Journal of Religion and Health, 46(1), 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauli, R. P., & Mulyono, S. (2019). The correlation between spirituality level and emotional resilience in school-aged children in SDN Kayuringin Jaya South Bekasi. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing, 42(Suppl. 1), 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelms, L. W., Hutchins, E., Hutchins, D., & Pursley, R. J. (2007). Spirituality and the health of college students. Journal of Religion and Health, 46(2), 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, C. J. (2023). The intersectionality of spirituality and moral development among college seniors: A narrative inquiry [Doctoral dissertation, University of Phoenix]. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372042116 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Ononye, U., Ogbeta, M., Ndudi, F., Bereprebofa, D., & Maduemezia, I. (2021). Academic resilience, emotional intelligence, and academic performance among undergraduate students. Knowledge and Performance Management, 23(3), 461–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pansini, M., Buonomo, I., & Benevene, P. (2024). Fostering sustainable workplace through leaders’ compassionate behaviors: Understanding the role of employee well-being and work engagement. Sustainability, 16(23), 10697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K., Feuille, M., & Burdzy, D. (2011). The brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions, 2(1), 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosyants, V. P. (2017). Features of resilience in psychology students depending on the year of study. Psychological Science and Education, 22(6), 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, S., Neuer Colburn, A. A., Underwood, L., & Bayne, H. (2019). The impact of religion/spirituality on acculturative stress among international students. Journal of College Counseling, 22(1), 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S., Watson, A., Young, C. D., Peterson, C., Thomas, D., Anderson, M., & Watson, S. B. (2024). A descriptive study on holistic nursing education: Student perspectives on integrating mindfulness, spirituality, and professionalism. Nurse Education Today, 143, 106379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, A., & Ghazi, M. H. (2023). Relationship between spirituality and mental health conditions among undergraduate students. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 38(4), 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Sinkovics, N., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2023). A perspective on using partial least squares structural equation modeling in data articles. Data in Brief, 48, 109074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, A., Sellon, A., Cherry, S. T., Hunter-Jones, J., & Winslow, H. (2020). Impact of spirituality on resilience and coping during the COVID-19 crisis: A mixed-method approach investigating the impact on women. Health Care for Women International, 41(11–12), 1313–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L., Giske, T., van Leeuwen, R., Baldacchino, D., McSherry, W., Narayanasamy, A., Jarvis, P., & Schep-Akkerman, A. (2016). Factors contributing to student nurses’/midwives’ perceived competency in spiritual care. Nurse Education Today, 36, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghifard, Y., Veisani, Y., Mohamadian, F., Azizifar, A., Naghipour, S., & Aibod, S. (2020). Relationship between aggression and individual resilience with the mediating role of spirituality in academic students—A path analysis. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 9(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalm, F. D., Zandavalli, R. B., de Castro Filho, E. D., & Lucchetti, G. (2022). Is there a relationship between spirituality/religiosity and resilience? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(5), 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano Solórzano, S. S., Pizarro Romero, J. M., Díaz Cueva, J. G., Arias Montero, J. E., Zamora Campoverde, M. A., Lozzelli Valarezo, M. M., Montes Ninaquispe, J. C., Acosta Enriquez, B. G., & Arbulú Ballesteros, M. A. (2024). Acceptance of artificial intelligence and its effect on entrepreneurial intention in foreign trade students: A mirror analysis. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterk Barrett, M. C. (2023). Fostering undergraduate spiritual development in a competitive, digital world. In Supporting children and youth through spiritual education (pp. 308–327). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S., Rajagopalan, U., & Ibrahim, I. (2024). Financial sustainability through literacy and retirement preparedness. Sustainability, 16(23), 10692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M., Holdsworth, S., & Scott-Young, C. M. (2017). Resilience at University: The development and testing of a new measure. Higher Education Research and Development, 36(2), 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, K. J. C., Velita, J. J. A., Martinez, T. A., & Ferrer, R. M. (2024). Determinant factors of entrepreneurial culture in university students: An analysis from the theory of planned behavior at a Peruvian University. Sustainability, 16(23), 10693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R. (2015). Psychological health and needs research developments (p. 187). Nova Science Pub Inc. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84956717103&partnerID=40&md5=18479899d4e19030af65afb58834f55b (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Womble, M. N., Labbé, E. E., & Cochran, C. R. (2013). Spirituality and personality: Understanding their relationship to health resilience. Psychological Reports, 112(3), 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, J. H., Park, C. L., & Edmondson, D. (2012). Spiritual struggle and adjustment to loss in college students: Moderation by denomination. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 22(4), 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A., Anwer, N., Mahapatra, K., Shrivastava, M. K., & Khatiwada, D. (2024). Analyzing the role of polycentric governance in institutional innovations: Insights from urban climate governance in India. Sustainability, 16(23), 10736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Du, D., & Zhen, S. (2011). Belief systems and positive youth development among Chinese and American youth. In Thriving and spirituality among youth: Research perspectives and future possibilities (pp. 309–331). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhdiyah, Z., Darmayanti, K. K. H., & Khodijah, N. (2023). The significance of religious tolerance for university students: Its influence on religious beliefs and happiness. Islamic Guidance and Counseling Journal, 6(1), 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | fi | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 271 | 59.04 |

| Male | 121 | 26.36 |

| Prefer not to answer | 67 | 14.60 |

| Age group | ||

| 18–19 years old | 168 | 36.60 |

| 20–24 years old | 167 | 36.38 |

| 25–29 years old | 26 | 5.66 |

| 30 or more years old | 31 | 6.75 |

| Missing data | 67 | 14.60 |

| Religious beliefs | ||

| High (scores 4–5) | 107 | 23.31 |

| Moderate (score 3) | 239 | 52.07 |

| Low (scores 1–2) | 113 | 24.62 |

| Academic year | ||

| First year | 160 | 34.86 |

| Second year | 58 | 12.64 |

| Third year | 116 | 25.27 |

| Fourth year | 35 | 7.62 |

| Fifth year | 7 | 1.53 |

| Sixth year | 16 | 3.49 |

| Missing data | 67 | 14.60 |

| Faculty/School | ||

| Faculty of Engineering | 186 | 40.52 |

| Faculty of Sciences | 142 | 30.94 |

| Faculty of Natural Resources | 89 | 19.39 |

| Faculty of Agriculture | 42 | 9.15 |

| University type | ||

| Public university | 278 | 60.57 |

| Private university | 181 | 39.43 |

| Degree program | ||

| Environmental Engineering | 198 | 43.14 |

| Environmental Sciences | 134 | 29.19 |

| Ecology and Natural Resources | 87 | 18.95 |

| Forestry Engineering | 40 | 8.72 |

| Academic performance | ||

| High (GPA ≥ 16/20) | 127 | 27.67 |

| Medium (GPA 13–15.9/20) | 245 | 53.38 |

| Low (GPA < 13/20) | 87 | 18.95 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| High | 78 | 17.00 |

| Medium | 298 | 64.92 |

| Low | 83 | 18.08 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 312 | 67.97 |

| Rural | 89 | 19.39 |

| Semiurban | 58 | 12.64 |

| Employment status | ||

| Student only | 289 | 62.96 |

| Part-time work | 132 | 28.76 |

| Full-time work | 38 | 8.28 |

| Items | Factor Loading | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | p Values | AVE | Construct | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In general, I consider myself: 1 = A not very happy person; 7 = A very happy person. | HAP1 | 0.722 | 0.043 | 0.000 | 0.594 | Happiness (HAP) |

| Compared to most of my friends and/or colleagues, I consider myself to be 1 = Less Happy; 7 = Happiest | HAP2 | 0.735 | 0.064 | 0.000 | ||

| Some people are very happy. They enjoy life no matter what happens, they make the most of everything. To what extent does this characterization describe you? 1 = Not at all; 7 = A lot | HAP3 | 0.879 | 0.029 | 0.000 | ||

| Some people are very happy. Even if they have good reasons to feel sad, they can always be as happy as they want to be. To what extent does this description represent you? 1 = Not at all; 7 = A lot | HAP4 | 0.745 | 0.045 | 0.000 | ||

| I am able to adapt when changes arise. | RES1 | 0.769 | 0.060 | 0.000 | 0.652 | Resilience (RES) |

| I am able to handle unpleasant/painful unpleasant/painful feelings such as sadness, fear and anger. | RES10 | 0.834 | 0.039 | 0.000 | ||

| I can cope with anything. | RES2 | 0.809 | 0.051 | 0.000 | ||

| When I face problems, I try to see the positive side of them. | RES3 | 0.778 | 0.033 | 0.000 | ||

| Facing difficulties can make me stronger. | RES4 | 0.889 | 0.048 | 0.000 | ||

| I tend to recover quickly after illness, injury or other difficulties. | RES5 | 0.805 | 0.037 | 0.000 | ||

| I believe I can achieve my goals, even if there are obstacles. | RES6 | 0.898 | 0.051 | 0.000 | ||

| Under pressure, I stay focused and think clearly. | RES7 | 0.843 | 0.053 | 0.000 | ||

| I am not easily discouraged by failure. | RES8 | 0.809 | 0.037 | 0.000 | ||

| I believe I am a strong person when faced with life challenges and difficulties. | RES9 | 0.709 | 0.036 | 0.000 | ||

| I believe in a higher being or force that provides me with support and sustenance in difficult times. | SPI1 | 0.854 | 0.056 | 0.000 | 0.754 | Spirituality (SPI) |

| I feel a sense of connection and harmony with myself. | SPI10 | 0.898 | 0.027 | 0.000 | ||

| I have a personal relationship with an upper being or force. | SPI11 | 0.747 | 0.037 | 0.000 | ||

| Sometimes I feel connected to the universe. | SPI12 | 0.889 | 0.039 | 0.000 | ||

| I practice meditation to get in touch with myself. | SPI2 | 0.876 | 0.059 | 0.000 | ||

| Accepting and respecting the diversity of people is a value for me. | SPI3 | 0.954 | 0.074 | 0.000 | ||

| My faith in a higher being or force helps me face the challenges in my life. | SPI4 | 0.865 | 0.041 | 0.000 | ||

| I practice silence to get in touch with myself. | SPI5 | 0.850 | 0.052 | 0.000 | ||

| Maintaining and strengthening my relationships with others is important to me. | SPI6 | 0.734 | 0.073 | 0.000 | ||

| All living beings deserve respect. | SPI7 | 0.865 | 0.082 | 0.000 | ||

| Helping other people is a value for me. | SPI8 | 0.875 | 0.067 | 0.000 | ||

| I practice prayer to get in touch with an upper being or force. | SPI9 | 0.845 | 0.039 | 0.000 | ||

| Construct | α | CR (rho_a) | CR (rho_c) | VIF | R2 | Q2 Predict | HAP | RES | SPI | HTMT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAP | 0.779 | 0.789 | 0.876 | 1.673 | 0.862 | 0.899 | 0.776 | 0.402 | ||

| RES | 0.869 | 0.875 | 0.845 | 1.132 | 0.971 | 0.979 | 0.430 | 0.874 | 0.251 | |

| SPI | 0.855 | 0.789 | 0.886 | 1.849 | - | - | 0.598 | 0.374 | 0.781 | 0.288 |

| Criteria | Estimated Model | Threshold | Author | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.073 | <0.85 | (Gaskin, 2022) | Acceptable |

| d_ULS | 2.250 | |||

| d_G | 0.552 | |||

| χ2/df | 1.763 | Between 1 and 3 | (Escobedo Portillo et al., 2016) | Acceptable |

| NFI | 0.998 | >0.90 | (Escobedo Portillo et al., 2016) | Acceptable |

| Hypothesis | β | p Value | Percentile | SD | Decision | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.50% | 97.50% | ||||||

| H2 | RES ⟶ HAP | 0.162 | 0.013 | 0.044 | 0.299 | 0.065 | Accepted |

| H1 | SPI ⟶ HAP | 0.256 | 0.000 | 0.160 | 0.357 | 0.051 | Accepted |

| H3 | SPI ⟶ RES | 0.274 | 0.000 | 0.175 | 0.407 | 0.060 | Accepted |

| H5 | Religious Belief × RES ⟶ HAP | 0.032 | 0.489 | −0.057 | 0.125 | 0.047 | Rejected |

| H4 | Year of study × SPI ⟶ HAP | −0.047 | 0.443 | −0.152 | 0.092 | 0.062 | Rejected |

| Construct | RES | SPI | HAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| HAP | 0.789 | 0.865 | - |

| RES | - | 0.911 | 0.845 |

| SPI | 0.852 | - | 0.946 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reyes-Perez, M.D.; Carreño Saucedo, L.; Sanchez-Levano, M.J.; Cabanillas-Palomino, R.; Monje-Yovera, P.F.; Jaime-Rodríguez, J.P.; Atoche-Silva, L.A.; Alarcón-Bustíos, J.M.; Fernández-Altamirano, A.E.F. The Spirituality–Resilience–Happiness Triad: A High-Powered Model for Understanding University Student Well-Being. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080158

Reyes-Perez MD, Carreño Saucedo L, Sanchez-Levano MJ, Cabanillas-Palomino R, Monje-Yovera PF, Jaime-Rodríguez JP, Atoche-Silva LA, Alarcón-Bustíos JM, Fernández-Altamirano AEF. The Spirituality–Resilience–Happiness Triad: A High-Powered Model for Understanding University Student Well-Being. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(8):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080158

Chicago/Turabian StyleReyes-Perez, Moises David, Leticia Carreño Saucedo, María Julia Sanchez-Levano, Roxana Cabanillas-Palomino, Paola Fiorella Monje-Yovera, Johan Pablo Jaime-Rodríguez, Luz Angelica Atoche-Silva, Johannes Michael Alarcón-Bustíos, and Antony Esmit Franco Fernández-Altamirano. 2025. "The Spirituality–Resilience–Happiness Triad: A High-Powered Model for Understanding University Student Well-Being" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 8: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080158

APA StyleReyes-Perez, M. D., Carreño Saucedo, L., Sanchez-Levano, M. J., Cabanillas-Palomino, R., Monje-Yovera, P. F., Jaime-Rodríguez, J. P., Atoche-Silva, L. A., Alarcón-Bustíos, J. M., & Fernández-Altamirano, A. E. F. (2025). The Spirituality–Resilience–Happiness Triad: A High-Powered Model for Understanding University Student Well-Being. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(8), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080158