The Quality of the Parent–Child Relationship in the Context of Autism: The Role of Parental Resolution of the Child’s Diagnosis, Parenting Stress, and Caregiving Burden

Abstract

1. The Quality of the Parent–Child Relationship in the Context of Autism

1.1. Parental Factors Affecting the Quality of the Parent–Child Relationship in the Context of Autism

1.1.1. Parental Resolution of a Child’s Autism Diagnosis and the Quality of the Parent–Child Relationship

1.1.2. Parenting Stress and the Quality of the Parent–Child Relationship

1.1.3. Caregiving Burden and the Quality of the Parent–Child Relationship

- This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and Statistical Plan

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Potential Predictor

2.3.2. Mediators

2.3.3. Outcome

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary and Descriptive Analyses

3.2. Group Comparisons

3.3. Correlational Analysis

3.4. Multiple Mediation Model

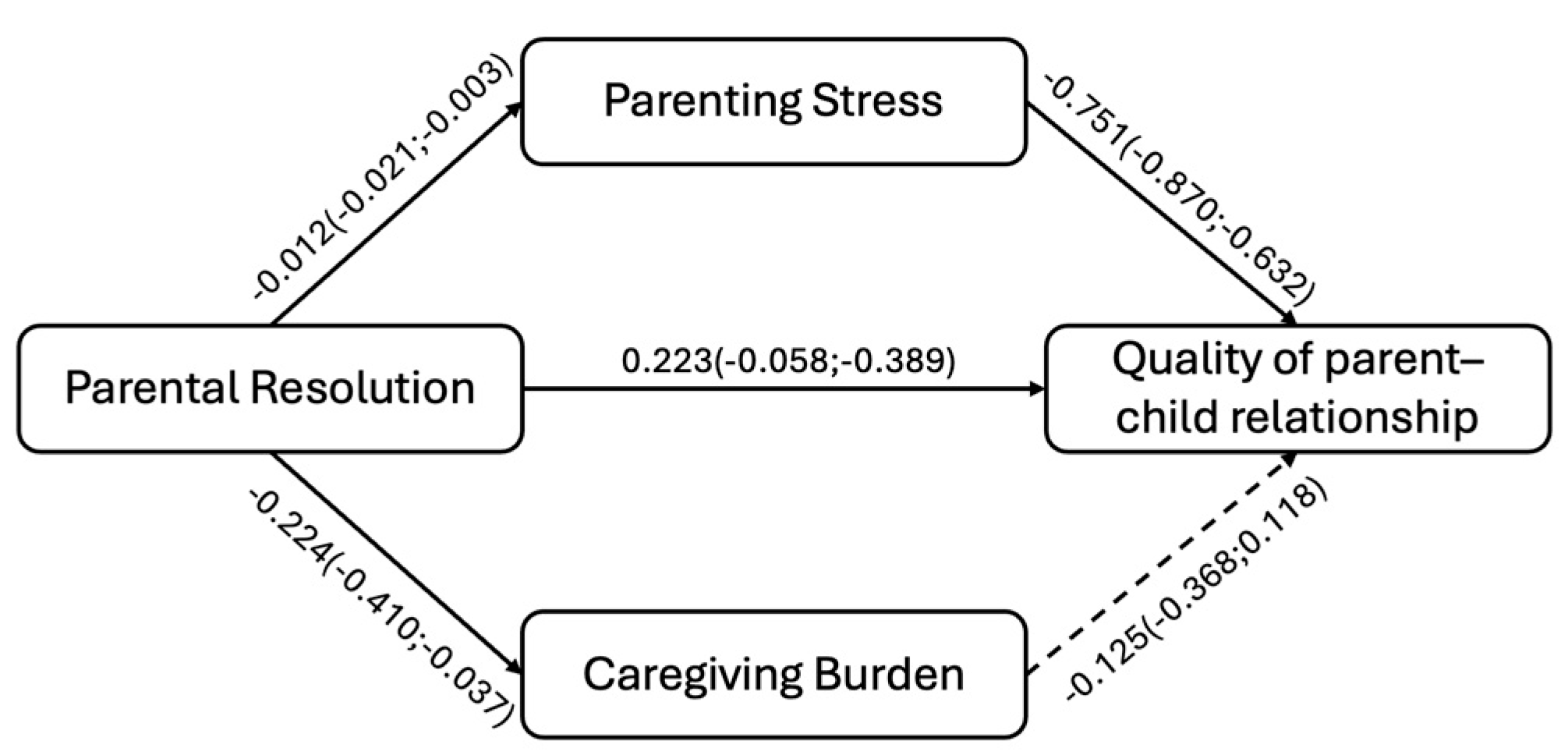

4. Discussion and Future Directions

4.1. The Main Model

4.1.1. The Role of Parenting Stress and Caregiving Burden

4.1.2. The Role of Parental Resolution

5. Practical and Clinical Implications

6. Limitations and Strengths

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abidin, R. R. (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21(4), 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, R. D., Tmanova, L. L., Delgado, D., Dion, S., & Lachs, M. S. (2014). Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA, 311(10), 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akister, J., & Johnson, K. (2004). The parenting task: Parent’s concerns and where they would seek help. Journal of Family Social Work, 8(2), 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, C., Green, J., Emsley, R., & McConachie, H. (2012). Brief report: Mediation of treatment effect in a communication intervention for pre-school children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H. H., Nazir, M., & Munir, B. (2025). A meta-analysis of screening tools for autism spectrum disorder: Efficacy, reliability, and practical application. Research Journal for Social Affairs, 3(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Almansour, M. A., Alateeq, M. A., Alzahrani, M. K., Algeffari, M. A., & Alhomaidan, H. T. (2013). Depression and anxiety among parents and caregivers of autistic spectral disorder children. Neurosciences, 18(1), 58–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, N. E., Mendez, L., Graziano, P. A., & Bagner, D. M. (2018). Parenting stress through the lens of different clinical groups: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(3), 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baykal, S., Karakurt, M. N., Çakır, M., & Karabekiroğlu, K. (2019). An examination of the relations between symptom distributions in children diagnosed with autism and caregiver burden, anxiety and depression levels. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(3), 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello-Mojeed, M., Omigbodun, O., Ogun, O., & Adewuya, B. (2013). The relationship between the pattern of impairments in autism spectrum disorder and maternal psychosocial burden of care. OA Autism, 1(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsika, V., Sharpley, C. F., & Bell, R. (2013). The buffering effect of resilience upon stress, anxiety, and depression in parents of a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 25(5), 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesi, G., Ghisi, M., Altoè, G., Conforti, E., Melli, G., & Sica, C. (2015). The Italian version of the depression anxiety stress scales-21: Factor structure and psychometric properties on community and clinical samples. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 60, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss (Vol. 1). Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 793–828). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cassibba, R., Coppola, G., Sette, G., Curci, A., & Costantini, A. (2017). The transmission of attachment across three generations: A study in adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 53(2), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano, D., Holloway, L., & Mpofu, E. (2018). Mental health interventions for parent carers of children with autistic spectrum disorder: Practice guidelines from a critical interpretive synthesis (CIS) systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetinbakis, G., Bastug, G., & Ozel-Kizil, E. T. (2020). Factors contributing to higher caregiving burden in Turkish mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 66(1), 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattat, R., Cortesi, V., Izzicupo, F., Del Re, M. L., Sgarbi, C., Fabbo, A., & Bergonzini, E. (2011). The Italian version of the zarit burden interview: A validation study. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(5), 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombi, C., Chericoni, N., Bargagna, S., Costanzo, V., Devescovi, R., Lecciso, F., Pierotti, C., Prosperi, M., & Contaldo, A. (2023). Case report: Preemptive intervention for an infant with early signs of autism spectrum disorder during the first year of life. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, G., Costantini, A., Tedone, R., Pasquale, S., Elia, L., Barbaro, M. F., & d’Addetta, I. (2012). The impact of the baby’s congenital malformation on the mother’s psychological well-being: An empirical contribution on the clubfoot. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 32(5), 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Paz, N. S., Siegel, B., Coccia, M. A., & Epel, E. S. (2018). Acceptance or despair? Maternal adjustment to having a child diagnosed with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(6), 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Paz, N. S., & Wallander, J. L. (2017). Interventions that target improvements in mental health for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A narrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardas, L. A., & Ahmad, M. M. (2014). Quality of life among parents of children with autistic disorder: A sample from the Arab world. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(2), 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, N. O., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(12), 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carlo, E., Martis, C., Lecciso, F., Levante, A., Signore, F., & Ingusci, E. (2024). Acceptance of disability as a protective factor for emotional exhaustion: An empirical study on employed and unemployed persons with disabilities. Psicologia Sociale, 18(2), 235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, A., Vismara, L., Mercado, C., Fitzpatrick, A., Elder, L., Greenson, J., Lord, C., Munson, J., Winter, J., Young, G., & Dawson, G. (2014). The impact of parent-delivered intervention on parents of very young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(2), 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, S. L., Abel, T., & Brodkin, E. S. (2018). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: A review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(2), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingerman, K. L., Huo, M., & Birditt, K. S. (2020). Mothers, fathers, daughters, and sons: Gender differences in adults’ intergenerational ties. Journal of Family Issues, 41(9), 1597–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonagy, P., Campbell, C., & Campbell, C. (2016). Attachment theory and mentalization. In P. Fonagy, C. Campbell, & C. Campbell (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of psychoanalysis in the social sciences and humanities (pp. 69–82). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanizadeh, A., Alishahi, M. J., & Ashkani, H. (2009). Helping families for caring children with autistic spectrum disorders. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 12(5), 478–482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Giallo, R., Wood, C. E., Jellett, R., & Porter, R. (2013). Fatigue, wellbeing and parental self-efficacy in mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 17(4), 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Given, B., Kozachik, S., Collins, C., Devoss, D., & Given, C. W. (2001). Caregiver role strain. In M. Maas (Ed.), Nursing care of older adults: Diagnosis, outcomes and interventions (pp. 679–695). Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, R. P. (2003). Child behavior problems and partner mental health as correlates of stress in mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47(3), 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haven, E. L., Manangan, C. N., Sparrow, J. K., & Wilson, B. J. (2014). The relation of parent–child interaction qualities to social skills in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 18(3), 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, E. J., Hartley, S. L., & Papp, L. (2020). Psychological well-being and parent–child relationship quality in relation to child autism: An actor–partner modeling approach. Family Process, 59(2), 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschler-Guttenberg, Y., Golan, O., Ostfeld-Etzion, S., & Feldman, R. (2015). Mothering, fathering, and the regulation of negative and positive emotions in high-functioning preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(5), 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Corp. (2023). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 29.0.2.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jhuo, R. A., & Chu, S. Y. (2022). A review of parent-implemented early start denver model for children with autism spectrum disorder. Children, 9(2), 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A., & Lee, B. (2021). Parenting approaches and their impact on children with autism spectrum disorder: A focus on positive reinforcement and structured routines. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(6), 1980–1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kamphorst, K., Brouwer, A. J., Poslawsky, I. E., Ketelaar, M., Ockhuisen, H., & Van Den Hoogen, A. (2018). Parental presence and activities in a Dutch neonatal intensive care unit: An observational study. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 32(3), E3–E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Koren-Karie, N., Oppenheim, D., Dolev, S., & Yirmiya, N. (2009). Mothers of securely attached children with autism spectrum disorder are more sensitive than mothers of insecurely attached children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(6), 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kübler-Ross, E. (1973). On death and dying. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lecciso, F., Levante, A., Signore, F., & Petrocchi, S. (2019). Preliminary evidence of the structural validity and measurement invariance of the Quantitative-CHecklist for Autism in toddler (Q-CHAT) on Italian unselected children. Electronic Journal of Applied Statistical Analysis, 12(2), 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecciso, F., Martis, C., Antonioli, G., & Levante, A. (2025a). The impact of the reaction to diagnosis on sibling relationship: A study on parents and adult siblings of people with disabilities. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1551953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecciso, F., Martis, C., Del Prete, C. M., Martino, P., Primiceri, P., & Levante, A. (2025b). Determinants of sibling relationships in the context of mental disorders. PLoS ONE, 20(4), e0322359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecciso, F., Martis, C., & Levante, A. (2025c). The use of Griffiths III in the appraisal of the developmental profile in Autism: A systematic search and review. Brain Sciences, 15(5), 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecciso, F., Petrocchi, S., Liverta Sempio, O., & Marchetti, A. (2011). Un contributo per un nuovo strumento di misura della fiducia tra affetti e mentalizzazione: La Trust Story. Psicologia Clinica dello Sviluppo, 15(1), 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lecciso, F., Petrocchi, S., Savazzi, F., Marchetti, A., Nobile, M., & Molteni, M. (2013). The association between maternal resolution of the diagnosis of autism, maternal mental representations of the relationship with the child, and children’s attachment. Life Span Disabilities, 16(1), 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Levante, A., Martis, C., Del Prete, C. M., Martino, P., Pascali, F., Primiceri, P., Vergari, M., & Lecciso, F. (2023). Parentification, distress, and relationship with parents as factors shaping the relationship between adult siblings and their brother/sister with disabilities. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 1079608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levante, A., Martis, C., Del Prete, C. M., Martino, P., Primiceri, P., & Lecciso, F. (2024). Siblings of persons with disabilities: A systematic integrative review of the empirical literature. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 28, 209–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levante, A., Martis, C., Gemma, M., & Lecciso, F. (2025). Paternal child-focused reflective functioning, parental sense of competence, and parental emotions recognition. Family Relations, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, J., Yoder, M. K., & Canham, D. (2009). Southeast Asian parents raising a child with autism: A qualitative investigation of coping styles. Journal of School Nursing, 25(3), 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Main, M., & Hesse, E. (1990). Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened and/or frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism? In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 161–182). The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, A., Castelli, I., Cavalli, G., Di Terlizzi, E., Lecciso, F., Lucchini, B., Massaro, D., Petrocchi, S., & Valle, A. (2013). Theory of mind in typical and atypical developmental settings: Some considerations from a contextual perspective. In Reflective thinking in educational settings: A cultural framework (pp. 102–136). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marsack-Topolewski, C. N., & Church, H. L. (2019). Impact of caregiver burden on quality of life for parents of adult children with autism spectrum disorder. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 124(2), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martis, C., Levante, A., De Carlo, E., Ingusci, E., Signore, F., & Lecciso, F. (2024). The power of acceptance of their disability for improving flourishing: Preliminary insights from persons with physical acquired disabilities. Disabilities, 4(4), 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvin, R. S., & Pianta, R. C. (1996). Mothers’ reactions to their child’s diagnosis: Relations with security of attachment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(4), 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskey, M., Warnell, F., Parr, J. R., Le Couteur, A., & McConachie, H. (2013). Emotional and behavioural problems in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(4), 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McStay, R. L., Dissanayake, C., Scheeren, A., Koot, H. M., & Begeer, S. (2014). Parenting stress and autism: The role of age, autism severity, quality of life and problem behaviour of children and adolescents with autism. Autism, 18(5), 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minhas, A., Vajaratkar, V., Divan, G., Hamdani, S. U., Leadbitter, K., Taylor, C., & Cardoza, P. (2015). Parents’ perspectives on care of children with autistic spectrum disorder in South Asia—Views from Pakistan and India. International Review of Psychiatry, 27(3), 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naicker, V. V., Bury, S. M., & Hedley, D. (2023). Factors associated with parental resolution of a child’s autism diagnosis: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 1079371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, A., Schiavi, S., La Rosa, P., Rossi-Espagnet, M. C., Petrillo, S., Bottino, F., Tagliente, E., Longo, D., Lupi, E., Casula, L., & Valeri, G. (2022). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: Diagnostic, neurobiological, and behavioral features. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 889636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoye, C., Obialo-Ibeawuchi, C. M., Obajeun, O. A., Sarwar, S., Tawfik, C., Waleed, M. S., Wasim, A. U., Mohamoud, I., Afolayan, A. Y., & Mbaezue, R. N. (2023). Early diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: A review and analysis of the risks and benefits. Cureus, 15(8), e43226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppenheim, D., Koren-Karie, N., Dolev, S., & Yirmiya, N. (2009). Maternal insightfulness and resolution of the diagnosis are associated with secure attachment in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Child Development, 80(2), 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, L. A., McHugh, L., Saunders, J., & Reed, P. (2008). Parenting stress reduces the effectiveness of early teaching interventions for autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(6), 1092–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, Y., Riccadonna, S., & Venuti, P. (2014). Parenting dimensions in mothers and fathers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(10), 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Cerezuela, G., Fernández-Andrés, M. I., Tárraga-Mínguez, R., & Navarro-Peña, J. M. (2016). Parental stress and ASD: Relationship with autism symptom severity, IQ, and resilience. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31(4), 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. D., Arya, A., Agarwal, V., Gupta, P. K., & Agarwal, M. (2022). Burden of care and quality of life in caregivers of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 70, 103030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetrasuwan, S., & Shandor Miles, M. (2009). Parenting stress in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 14(3), 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pianta, R. C. (1992). Child–parent relationship scale. Journal of Early Childhood and Infant Psychology, 1(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R. C., & Steinberg, M. (1992). Teacher-child relationships and the process of adjusting to school. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R. C., & Stuhlman, M. W. (2004). Teacher-child relationships and children’s success in the first years of school. School Psychology Review, 33(4), 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisula, E. (2007). A comparative study of stress profiles in mothers of children with autism and those of children with Down’s syndrome. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20(4), 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijneveld, S. A., de Meer, G., Wiefferink, C. H., & Crone, M. R. (2008). Parents’ concerns about children are highly prevalent but often not confirmed by child doctors and nurses. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X., Cai, Y., Wang, J., & Chen, O. (2024). A systematic review of parental burnout and related factors among parents. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renty, J. O., & Roeyers, H. (2006). Quality of life in high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder: The predictive value of disability and support characteristics. Autism, 10(5), 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repetti, R. L., Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (2002). Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 330–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, T., Castelli, I., Palena, N., Greco, A., Pianta, R., Marchetti, A., & Valle, A. (2023). The representation of child–parent relation: Validation of the Italian version of the child–parent relationship scale (CPRS-I). Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1194644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivard, M., Terroux, A., Parent-Boursier, C., & Mercier, C. (2014). Determinants of stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, S. J., Estes, A., Lord, C., Vismara, L., Winter, J., Fitzpatrick, A., Guo, M., & Dawson, G. (2012). Effects of a brief early start denver model (ESDM)–based parent intervention on toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(10), 1052–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, M., Marín, E., Guzmán-Parra, J., Navas, P., Aguilar, J. M., Lara, J. P., & Barbancho, M. Á. (2021). Relationship between parental stress and psychological distress and emotional and behavioural problems in pre-school children with autistic spectrum disorder. Anales de Pediatría (English Edition), 94(2), 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, B. S., Hutchison, M., Tambling, R., Tomkunas, A. J., & Horton, A. L. (2020). Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: Caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent–child relationship. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51(5), 671–682. [Google Scholar]

- Schieve, L. A., Blumberg, S. J., Rice, C., Visser, S. N., & Boyle, C. (2007). The relationship between autism and parenting stress. Pediatrics, 119(Suppl. S1), S114–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiltz, H. K., McVey, A. J., Dolan Wozniak, B., Haendel, A. D., Stanley, R., Arias, A., Gordon, N., & Van Hecke, A. V. (2021). The role of loneliness as a mediator between autism features and mental health among autistic young adults. Autism, 25(2), 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seskin, L., Feliciano, E., Tippy, G., Yedloutschnig, R., Sossin, K. M., & Yasik, A. (2010). Attachment and autism: Parental attachment representations and relational behaviors in the parent-child dyad. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(7), 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, M., Wood, C., Giallo, R., & Jellett, R. (2013). Fatigue, stress, and coping in mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(6), 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher-Censor, E., Dan Ram-On, T., Rudstein-Sabbag, L., Watemberg, M., & Oppenheim, D. (2020). The reaction to diagnosis questionnaire: A preliminary validation of a new self-report measure to assess parents’ resolution of their child’s diagnosis. Attachment & Human Development, 22(4), 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher-Censor, E., Dolev, S., Said, M., Baransi, N., & Amara, K. (2017). Coherence of representations regarding the child, resolution of the child’s diagnosis, and emotional availability: A study of Arab-Israeli mothers of children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(12), 3139–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher-Censor, E., & Shahar-Lahav, R. (2022). Parents’ resolution of their child’s diagnosis: A scoping review. Attachment & Human Development, 24(4), 580–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siller, M., Hotez, E., Swanson, M., Delavenne, A., Hutman, T., & Sigman, M. (2018). Parent coaching increases the parents’ capacity for reflection and self-evaluation: Results from a clinical trial in autism. Attachment & human development, 20(3), 287–308. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E., Williams, K., & Martinez, A. (2022). The importance of parent-child dynamics in autism spectrum disorder intervention. Journal of Special Education, 45(3), 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. E., Hong, J., Seltzer, M. M., Greenberg, J. S., Almeida, D. M., & Bishop, S. L. (2010). Daily experiences among mothers of adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solak Arabaci, M., & Demircioğlu, H. (2021). Investigating predictive effects of 5–6-year-old children’s relationships with their parents and parents’ marital satisfaction on children’s relationships with their peers. Early Child Development and Care, 191(5), 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M., Ono, M., Timmer, S., & Goodlin-Jones, B. (2008). The effectiveness of parent–child interaction therapy for families of children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(10), 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, M., & McGrew, J. H. (2009). Caregiver burden after receiving a diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(1), 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanyam, A. A., Mukherjee, A., Dave, M., & Chavda, K. (2019). Clinical practice guidelines for autism spectrum disorders. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(Suppl. S2), 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Shannon, J. D., Cabrera, N. J., & Lamb, M. E. (2004). Fathers and mothers at play with their 2- and 3-year-olds: Contributions to language and cognitive development. Child Development, 75(5), 1806–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehee, E., Honan, R., & Hevey, D. (2009). Factors contributing to stress in parents of individuals with autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22(1), 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. (2024). Jamovi (Version 2.6) [Computer software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Tomanik, S., Harris, G. E., & Hawkins, J. (2004). The relationship between behaviours exhibited by children with autism and maternal stress. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 29(1), 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Emerson, E., & Hatton, C. (2020). Early years parenting mediates early adversity effects on problem behaviors in intellectual disability. Child Development, 91(3), e649–e664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valicenti-McDermott, M., Lawson, K., Hottinger, K., Seijo, R., Schechtman, M., Shulman, L., & Shinnar, S. (2015). Parental stress in families of children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Journal of Child Neurology, 30(12), 1728–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niekerk, K., Stancheva, V., & Smith, C. (2023). Caregiver burden among caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 29, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhage, M. L., Schuengel, C., Madigan, S., Fearon, R. M., Oosterman, M., Cassibba, R., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2016). Narrowing the transmission gap: A synthesis of three decades of research on intergenerational transmission of attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 142, 337–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachtel, K., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Reaction to diagnosis and parenting styles among mothers of young children with ASDs. Autism, 12(6), 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddington, H., van der Meer, L., Sigafoos, J., & Bowden, C. J. (2020). Mothers’ perceptions of a home-based training program based on the early start denver model. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 4, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. (2023). The influence of parenting styles on attachment styles and parental influence on children’s cognitive development. In SHS web of conferences (Vol. 180, p. 02026). EDP Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, D. M., & Geschwind, D. H. (2013). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. Current Opinion in Neurology, 26(2), 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesilkaya, M., & Magallón-Neri, E. (2024). Parental stress related to caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder and the benefit of mindfulness-based interventions for parental stress: A systematic review. SAGE Open, 14(2), 21582440241235033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, I., Harley, E. K., Green, S. A., Smith, K., & Kipke, M. D. (2014). How sex of children with autism spectrum disorders and access to treatment services relates to parental stress. Autism Research and Treatment, 2014, 721418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarit, S. H., Reever, K. E., & Bach-Peterson, J. (1980). Zarit burden interview. Gerontologist, 41, 652–657. [Google Scholar]

| Mean/n | SD/% | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents of Autistic Children | |||

| Gender | |||

| Mothers | 44 | 86.3% | |

| Fathers | 7 | 13.7% | |

| Age (years) | 43.86 | 5.97 | 25–58 |

| Marital status | |||

| With a partner | 40 | 78.6% | |

| Without a partner | 11 | 21.6% | |

| Education level | |||

| Low | 3 | 5.9% | |

| Intermediate | 42 | 82.4% | |

| High | 6 | 11.7% | |

| Source of child’s diagnosis communication | |||

| My partner | 1 | 2.2% | |

| Healthcare providers | 30 | 58.6% | |

| Myself | 18 | 35.3% | |

| I asked others | 2 | 3.9% | |

| Autistic Children | |||

| Gender | |||

| Females | 10 | 19.6% | |

| Males | 41 | 80.4% | |

| Age (years) | 10.96 | 3.49 | 4–17 |

| Age range | |||

| Childhood | 24 | 47% | |

| Preadolescence | 13 | 25.5% | |

| Adolescence | 14 | 27.5% | |

| Age at diagnosis (months) | 42.71 | 18.5 | 18–108 |

| Birth order | |||

| First born | 11 | 21.6% | |

| Second born | 32 | 62.7% | |

| Third born or later | 8 | 15.7% | |

| Study Variables | M (SD) | Theoretical Range |

|---|---|---|

| Potential Predictor | ||

| Resolution Total Score | 3.67 (0.39) | 1–5 |

| Mediators | ||

| Parenting Stress | 0.91 (0.54) | 0–3 |

| Caregiving Burden | 33.68 (14.49) | 0–88 |

| Outcome | ||

| Quality of Parent–Child Relationship | ||

| Closeness | 17.25 (3.87) | 1–25 |

| Conflict | 29.94 (7.99) | 1–70 |

| Dependence | 10.27 (3.24) | 1–20 |

| Total score | 85.04 (11.35) | 1–115 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental resolution | −0.349 ** | −0.464 *** | 0.497 *** | −0.437 *** | −0.169 | 0.526 *** | −0.017 | 0.024 |

| Parenting Stress (1) | 0.692 *** | −0.471 *** | 0.464 *** | 0.376 ** | −0.594 *** | 0.055 | 0.042 | |

| Caregiving burden (2) | −0.383 ** | 0.441 *** | 0.435 *** | −0.565 *** | 0.080 | 0.005 | ||

| Closeness (3) | −0.286 * | 0.042 | 0.530 *** | −0.259 | −0.244 | |||

| Conflict (4) | 0.442 *** | −0.928 *** | −0.116 | 0.099 | ||||

| Dependence (5) | −0.582 *** | −0.036 | −0.197 | |||||

| Quality of the parent–child relationship (6) | 0.003 | −0.096 | ||||||

| Parents’ age (7) | 0.322 * | |||||||

| Child’s age (8) | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levante, A.; Martis, C.; Lecciso, F. The Quality of the Parent–Child Relationship in the Context of Autism: The Role of Parental Resolution of the Child’s Diagnosis, Parenting Stress, and Caregiving Burden. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070142

Levante A, Martis C, Lecciso F. The Quality of the Parent–Child Relationship in the Context of Autism: The Role of Parental Resolution of the Child’s Diagnosis, Parenting Stress, and Caregiving Burden. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(7):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070142

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevante, Annalisa, Chiara Martis, and Flavia Lecciso. 2025. "The Quality of the Parent–Child Relationship in the Context of Autism: The Role of Parental Resolution of the Child’s Diagnosis, Parenting Stress, and Caregiving Burden" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 7: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070142

APA StyleLevante, A., Martis, C., & Lecciso, F. (2025). The Quality of the Parent–Child Relationship in the Context of Autism: The Role of Parental Resolution of the Child’s Diagnosis, Parenting Stress, and Caregiving Burden. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(7), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070142