Pro-Health Behaviours and Depressive Symptoms as Well as Satisfaction with and Quality of Life Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

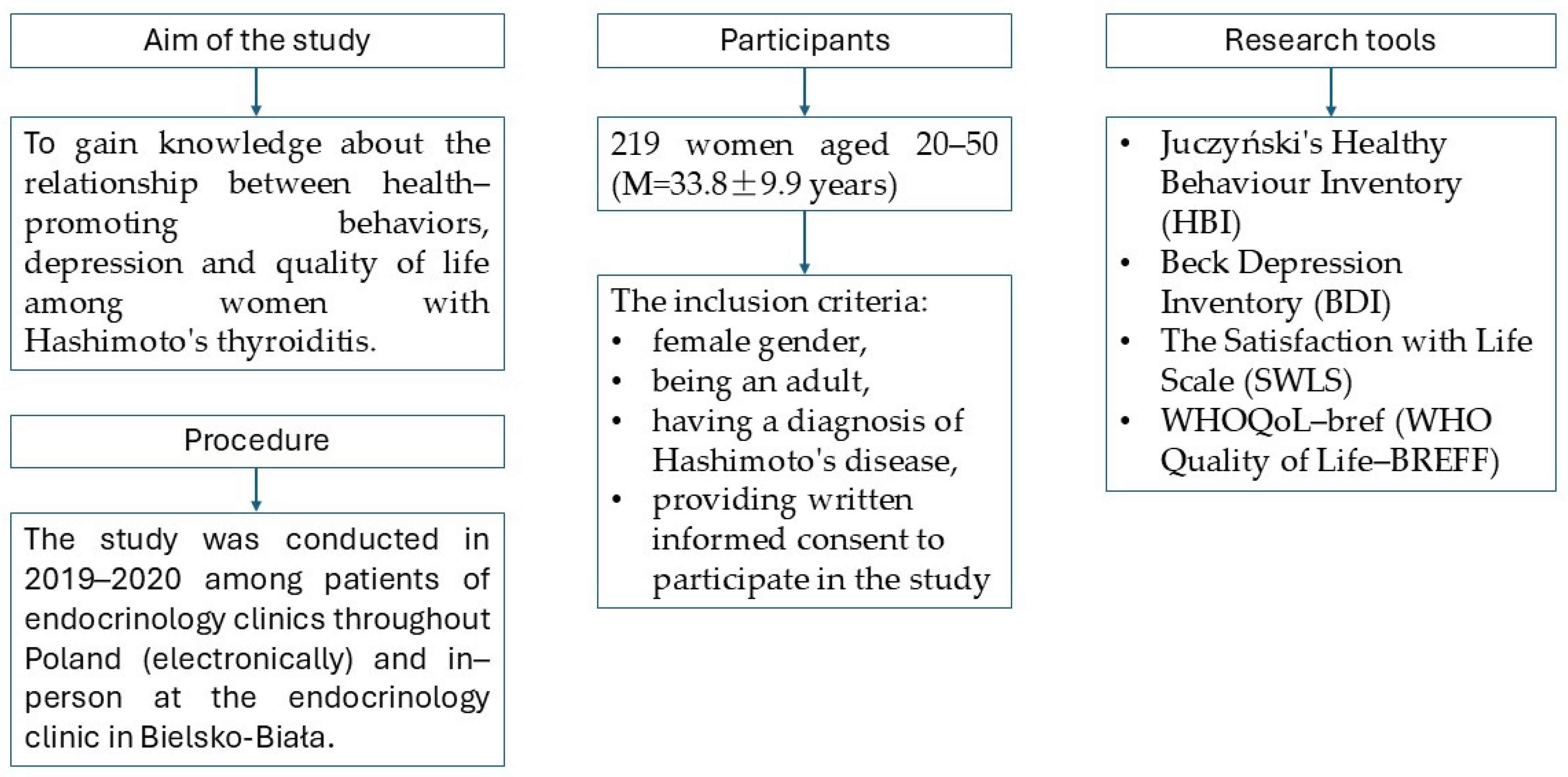

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Research Tools

- (a)

- Juczyński’s Healthy Behaviour Inventory (HBI), which contains 24 statements describing various categories of health-related behaviours. The questionnaire was used to assess the general index of pro-health behaviours, as well as the results in four categories of healthy behaviours (positive mental attitude, preventive behaviours, proper eating habits and pro-health practices). The general index of pro-health behaviours (HBI Total) ranges from 24 to 120 points, with a higher score indicating a higher level of pro-health behaviours. The reliability of the tool was checked using Cronbach’s Alpha, which was 0.90 for the entire tool (Juczyński, 2012).

- (b)

- Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI), which consists of 21 multiple choice questions (possible answers are scored from 0 to 3, i.e., from ‘no symptoms’ to a ‘strong symptom’). The questions refer to various symptoms of depression. In the interpretation of the results, it is assumed that obtaining 0–10 points means ‘no depression’ or ‘low depression’, i.e., ‘low mood’; 11–27 suggests ‘moderate depression’; and 28 or more indicates ‘severe depression’ (Beck et al., 1988; Jaracz et al., 2009). The severity of depressive symptoms in the studied group of women with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis was described in our previous paper. In the group was dominated by women without symptoms of depression or with low mood (53.9%), there were fewer women with moderate (38.4%) and severe depression (7.7%). The median scores in the BDI were 10.0, and mean scores were 11.9 (Gacek et al., 2025).

- (c)

- The satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) in the Polish adaptation by Z. Juczyński is used to measure life satisfaction. It contains five statements. The examined person assesses to what extent each of them refers to their life so far. The result of the measurement is a general indicator of the sense of satisfaction with life. The reliability coefficient of Cronbach’s α = 0.81, and similarly, the scale stability index equalled 0.86. The results range from 5 to 35, and the higher the score, the higher the level of life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985; Juczyński, 2012).

- (d)

- WHOQoL-bref (Quality of Life-BREFF) questionnaire, in the Polish adaptation by Wołowicka and Jaracz (WHOQOL-BREF, 1996; Wołowicka & Jaracz, 2001). The scale is used to assess life quality of healthy and ill individuals (for cognitive and clinical purposes). It contains 26 questions allowing to assess quality of life profile in the scope of four life dimensions: physical (somatic), psychological, social and environmental.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Level of Pro-Health Behaviours Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease

3.2. Level of Life Satisfaction and Quality of Life Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease

3.3. Health-Promoting Behaviours and Depressive Symptoms Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease

3.4. Health-Promoting Behaviours and Life Satisfaction Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease

3.5. Pro-Health Behaviours and Quality of Life Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease

4. Discussion

4.1. Pro-Health Behaviours, Depressive Symptoms, Satisfaction with Life and Quality of Life Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease

4.2. Correlations Between Pro-Health Behaviours, Depressive Disorders, Satisfaction with Life and Quality of Life Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease

4.3. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkhatib, D., Shi, Z., & Ganji, V. (2024). Dietary patterns and hypothyroidism in U.S. adult population. Nutrients, 16, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashgar, R. I. (2021). Relationships between personal satisfaction, cardiovascular disease risk, and health promoting behavior among Arab American middle-aged women. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 36, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aucoin, M., LaChance, L., Naidoo, U., Remy, D., Shekdar, T., Sayar, N., Cardozo, V., Rawana, T., Chan, I., & Cooley, K. (2021). Diet and anxiety: A scoping review. Nutrients, 13, 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayhan, G. M., Uguz, F., Askin, R., & Gonen, M. S. (2014). The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in patients with euthyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: A comparative study. General Hospital Psychiatry, 36, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banakiewicz, A., Bednarczyk, A., & Kulik, A. (2021). Wsparcie społeczne i dobrostan w chorobie Hashimoto u kobiet w okresie dorosłości [Social support and well-being in Hashimoto’s disease among adult women]. Annales Universitatis Marie Curie-Skłodowska. Sectio J: Paedagogica Psychologia, 34, 177–189. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Carbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchetta, A., Traccis, F., Mosca, E., Serra, A., Tamburini, G., & Loviselli, A. (2016). Bipolar disorder and antithyroid antibodies: Review and case series. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogomolova, S., Zarnowiecki, D., Wilson, A., Fielder, A., Procter, N., Itsiopoulos, C., O’Dea, K., Strachan, J., Ballestrin, M., Champion, A., & Parletta, N. (2018). Dietary intervention for people with mental illness in South Australia. Health Promotion International, 33, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Vieira, J. G., & Cardoso, C. K. S. (2023). Efficacy of B-vitamins and vitamin D therapy in improving depressive and anxiety disorders: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition Neuroscience, 26, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canas-Simião, H., Reis, C., Carreiras, D., Espada-Santos, P., & Paiva, T. (2022). Health-related behaviors and perceived addictions: Predictors of depression during the COVID lockdown. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 210, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayres, L. C. F., de Salis, L. V. V., Rodrigues, G. S. P., Lengert, A. V. H., Biondi, A. P. C., Sargentini, L. D. B., Brisotti, J. L., Gomes, E., & de Oliveira, G. L. V. (2021). Detection of alterations in the gut microbiota and intestinal permeability in patients with Hashimoto thyroiditis. Frontiers in Immunology, 5, 579140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S. W. (2021). Chronic disease management, self-efficacy and quality of life. Journal of Nursing Research, 29, e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S., Peng, Y., Zhang, H., & Zou, Y. (2023). Relationship between thyroid function and dietary inflammatory index in Hashimoto thyroiditis patients. Medicine, 102, e35951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, V., Vasudeva, N., Sharma, S., & Kumar, A. (2022). Role of dietary supplements in thyroid diseases. Endocrine Metabolic & Immune Disorders—Drug Targets, 22, 985–996. [Google Scholar]

- Danailova, Y., Velikova, T., Nikolaev, G., Mitova, Z., Shinkov, A., Gagov, H., & Konakchieva, R. (2022). Nutritional management of thyroiditis of Hashimoto. International Journal of Molecular Science, 23, 5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degner, D., Meller, J., Bleich, S., Schlautmann, V., & Rüther, E. (2001). Affective disorders associated with autoimmune thyroiditis. Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences, 13, 532–533. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Grifin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, S., Sahbaz, N. A., Aksakal, N., Tutal, F., Torun, B. C., Yıldırım, N. K., Özkan, M., Ozcina, B., & Erbil, Y. (2017). Quality of life after thyroid surgery. Journal Endocrinological Investigation, 40, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duntas, L. H. (2023). Nutrition and thyroid disease. Current Opinion in Endocrinology Diabetes and Obesity, 30, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duñabeitia, I., González-Devesa, D., Varela-Martínez, S., Diz-Gómez, J. C., & Ayán-Pérez, C. (2023). Effect of physical exercise in people with hypothyroidism: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical & Laboratory Investigation, 83, 523–532. [Google Scholar]

- Ekinci, G. N., & Sanlier, N. (2023). The relationship between nutrition and depression in the life process: A mini-review. Experimental Gerontology, 172, 112072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J., Marx, W., Dash, S., Carney, R., Teasdale, S. B., Solmi, M., Stubbs, B., Schuch, F. B., Carvalho, A. F., Jacka, F., & Sarris, J. (2019). The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S., & Ehlert, U. (2018). Hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis functioning in anxiety disorders. A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety, 35, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumincelli, L., Mazzo, A., Martins, J. C. A., & Mendes, I. A. C. (2019). Quality of life and ethics: A concept analysis. Nursing Ethics, 26, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gacek, M. (2013a). Selected individual determinants of cereal, fruit and vegetable consumption among menopausal women in view of potential health risks. Menopause Review, 12, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, M. (2013b). Selected individual differences as predictors of milk product consumption in a group of perimenopausal women in the light of health hazards. Menopause Review, 4, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, M. (2014). Individual differences as predictors of dietary patterns among menopausal women with arterial hypertension. Menopause Review, 13, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, M., & Kędzior, J. (2018). Aktywność fizyczna i zachowania żywieniowe osób w wieku 20–40 lat z chorobą Hashimoto [Physical activity and nutritional behaviours of individuals aged 20–40 with Hashimoto’s disease]. In J. A. Pietrzyk (Ed.), Człowiek w zdrowiu i chorobie. Promocja zdrowia, pielęgnowanie i rehabilitacja [People in health and disease. Health promotion, care and rehabilitation] (pp. 56–67). PWSZ. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Gacek, M., & Wojtowicz, A. (2019). Life satisfaction and other determinants of eating behaviours among women aged 40–65 years with type 2 diabetes from the Krakow population. Menopause Review, 18, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, M., Wojtowicz, A., & Kędzior, J. (2025). Physical Activity, nutritional behaviours and depressive symptoms in women with Hashimoto’s disease. Healthcare, 13(6), 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, M., Wojtowicz, A., Kosiba, G., Majer, M., Gradek, J., Koteja, A., & Czerwińska-Ledwig, O. (2023). Satisfaction with life and nutritional behaviour, body composition, and functional fitness of women from the Kraków population participating in the “healthy active senior” programme. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheonea, T. C., Oancea, C. N., Mititelu, M., Lupu, E. C., Ioniță-Mîndrican, C. B., & Rogoveanu, I. (2023). Nutrition and mental well-being: Exploring connections and holistic approaches. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12, 7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Głąbska, D., Guzek, D., Groele, B., & Gutkowska, K. (2020). Fruit and vegetable intake and mental health in adults: A systematic review. Nutrients, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnacińska-Szymańska, M., Dardzińska, J. A., Majkowicz, M., & Małgorzewicz, S. (2012). Ocena jakości życia osób z nadmierną masą ciała za pomocą formularza WHOQoL-BREF [Assessing life quality of individuals with excessive body mass using the WHOQoL-BREF]. Endokrynologia Otyłość Zaburzenia Przemiany Materii, 8, 136–142. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Hamer, M., Endrighi, R., & Poole, L. (2012). Physical activity, stress reduction, and mood: Insight into immunological mechanisms. Methods in Molecular Biology, 934, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Haraldstad, K., Wahl, A., Andenæs, R., Andersen, J. R., Andersen, M. H., Beisland, E., Borge, C. R., Engebretsen, E., Eisemann, M., Halvorsrud, L., Hanssen, T. A., Haugstvedt, A., Haugland, T., Johansen, V. A., Larsen, M. H., Løvereide, L., Løyland, B., Kvarme, L. G., Moons, P., … LIVSFORSK network. (2019). A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Quality of Life Research, 28, 2641–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitzman, J. (2016). Zaburzenia depresyjne: DSM-5 selections [Depressive disorders: DSM-5 selections]. American Psychiatric Association. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ihnatowicz, P., Drywień, M., Wątor, P., & Wojsiat, J. (2020). The importance of nutritional factors and dietary management of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 27, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihnatowicz, P., Wątor, P., & Drywień, M. E. (2021). The importance of gluten exclusion in the management of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 28, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacka, F. N., O’Neil, A., Opie, R., Itsiopoulos, C., Cotton, S., Mohebbi, M., Castle, D., Dash, S., Mihalopoulos, C., Chatterton, M. L., Brazionis, L., Dean, O. M., Hodge, A. M., & Berk, M. (2017). A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Medicine, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, B. N., Lee, H. J., Joo, J. H., Park, E. C., & Jang, S. I. (2020). Association between health behaviours and depression: Findings from a national cross-sectional study in South Korea. BMC Psychiatry, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, J., & Kucharska, A. (2019). Postawy wobec zdrowia i żywienia a utrzymywanie należnej masy ciała wśród pacjentek z chorobą Hashimoto [Attitudes towards health, nutrition and maintaining proper body mass among patients with Hashimoto’s disease]. Hygeia Public Health, 54, 182–191. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Jaracz, M., Bieliński, M., Junik, R., Dąbrowiecki, S., Szczęsny, W., Chojnowski, J., & Borkowska, A. (2009). Zaburzenia pamięci operacyjnej, funkcji wykonawczych i objawy depresji u osób z patologiczną otyłością [Working memory, executive function and depressive symptoms in pathological obesity]. Psychiatria Polska, 6, 9–11. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Juczyński, Z. (2012). Narzędzia pomiaru w promocji i psychologii zdrowia [Measurement tools in health promotion and psychology]. Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Jureško, I., Pleić, N., Gunjača, I., Torlak, V., Brdar, D., Punda, A., Polašek, O., Hayward, C., Zemunik, T., & Babić Leko, M. (2024). The effect of mediterranean diet on thyroid gland activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25, 5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, W., Wiśniewska, K., Okręglicka, K., Pazura, I., & Nitsch-Osuch, A. (2023). Lifestyle intervention towards Mediterranean Diet, physical activity adherence and anthropometric parameters in normal weight women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome or Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis—Preliminary study. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 30, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiba, G., Gacek, M., Wojtowicz, A., & Bogacz-Walancik, A. (2016). Health-related behaviours, physical activity and perceived life satisfaction in the academic youth of pedagogical subjects in Cracow. Studies in Sport Humanities, 20, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiba, G., Gacek, M., Wojtowicz, A., & Majer, M. (2019). Level of knowledge regarding health as well as health education and pro-health behaviours among students of physical education and other teaching specialisation. Baltic Journal of Health and Physical Activity, 11, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, K., & Kudas, A. (2013). Wpływ zachowań zdrowotnych na jakość życia osób z [Influence of pro-health behaviours on quality of life of individuals experiencing heart failure]. Folia Cardiologica Excerpta, 8, 1–8. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Kurpas, D., Bąk, E., Seń, M., Wróblewska, I., & Mroczek, B. (2014). Jakość życia pacjentów kardiologii inwazyjnej [Quality of life among invasive cardiology patients]. Family Medicine & Primary Care Review, 16, 120–123. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Kurpas, D., Czech, T., & Mroczek, B. (2012). Jakość życia pacjentów z cukrzycą—Jakie znaczenie mają powikłania? [Quality of life in patients with diabetes—What do complications mean?]. Family Medicine & Primary Care Review, 14, 177–181. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Kvam, S., Kleppe, C. L., Nordhus, I. H., & Hovland, A. (2016). Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 202, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekurwale, V., Acharya, S., Shukla, S., & Kumar, S. (2023). Neuropsychiatric manifestations of thyroid diseases. Cureus, 15, e33987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I. C., Chen, H. H., Yeh, S. Y., Lin, C. L., & Kao, C. H. (2016). Risk of depression, chronic morbidities, and l-thyroxine treatment in Hashimoto thyroiditis in Taiwan: A nationwide cohort study. Medicine, 95, e2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopresti, A. L. (2019). It is time to investigate integrative approaches to enhance treatment outcomes for depression? Medical Hypotheses, 126, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markiewicz-Żukowska, R., Naliwajko, S., Bartosiuk, E., Sawicka, E., Omeljaniuk, W., & Borawska, M. (2011). Zawartość witamin w dietach kobiet z chorobą Hashimoto [Vitamin content in the diet of patients with Hashimoto disease]. Bromatologia i Chemia Toksykologiczna, 44, 539–543. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Markomanolaki, Z. S., Tigani, X., Siamatras, T., Bacopoulou, F., Tsartsalis, A., Artemiadis, A., Megalooikonomou, V., Vlachakis, D., Chrousos, G. P., & Darviri, C. (2019). Stress management in women with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Molecular Biochemistry, 8, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martino, G., Caputo, A., Vicario, C. M., Feldt-Rasmussen, U., Watt, T., Quattropani, M. C., Benvenga, S., & Vita, R. (2021). Emotional distress, and perceived quality of life in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 667237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W., Manger, S. H., Blencowe, M., Murray, G., Ho, F. Y., Lawn, S., Blumenthal, J. A., Schuch, F., Stubbs, B., Ruusunen, A., Desyibelew, H. D., Dinan, T. G., Jacka, F., Ravindran, A., Berk, M., & O’Neil, A. (2023). Clinical guidelines for the use of lifestyle-based mental health care in major depressive disorder: World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM) taskforce. World Journal of Biology Psychiatry, 24, 333–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, K., Stojanovska, L., Polenakovic, M., Bosevski, M., & Apostolopoulos, V. (2017). Exercise and mental health. Maturitas, 106, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulska, A. A., Karaźniewicz-Łada, M., Filipowicz, D., Ruchała, M., & Główka, F. K. (2022). Metabolic characteristics of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients and the role of microelements and diet in the disease management—An overview. International Journal of Molecular Science, 23, 6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundare, T., Adebowale, T. O., Borba, C. P. C., & Henderson, D. C. (2020). Correlates of depression and quality of life among patients with epilepsy in Nigeria. Epilepsy Research, 164, 106344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osowiecka, K., & Myszkowska-Ryciak, J. (2023). The influence of nutritional intervention in the treatment of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis—A systematic review. Nutrients, 15, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, J., Promberger, R., Kober, F., Neuhold, N., Tea, T., Huber, J. C., & Hermann, M. (2011). Hashimoto’s thyroiditis affects symptom load and quality of life unrelated to hypothyroidism: A prospective case-control study in women undergoing thyroidectomy for benign goiter. Thyroid, 21, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parletta, N., Zarnowiecki, D., Cho, J., Wilson, A., Bogomolova, S., Villani, A., Itsiopoulos, C., Niyonsenga, T., Blunden, S., Meyer, B., Segal, L., Baune, B. T., & O’Dea, K. (2017). A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutrition Neuroscience, 22, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepiora, P. A., Piepiora, Z. N., Stackeova, D., Bagińska, J., Gasienica-Walczak, B., & Caplova, P. (2025). Editoral: Physical culture for mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1537842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Promberger, R., Hermann, M., Pallikunnel, S. J., Seemann, R., Meusel, M., & Ott, J. (2014). Quality of life after thyroid surgery in women with benign euthyroid goiter: Influencing factors including Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. American Journal of Surgery, 207, 974–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Arbués, E., Martínez Abadía, B., Granada López, J. M., Echániz Serrano, E., Pellicer García, B., Juárez Vela, R., Guerrero Portillo, S., & Saéz Guinoa, M. (2019). Conducta alimentaria y su relación con el estrés, la ansiedad, la depresión y el insomnio en estudiantes universitarios [Eating behaviours and relationships with stress, anxiety, depression and insomnia in university students]. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 36, 1339–1345. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rayman, M. P. (2019). Multiple nutritional factors and thyroid disease, with particular reference to autoimmune thyroid disease. Proceedings of Nutrition Society, 78, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recchia, F., Leung, C. K., Chin, E. C., Fong, D. Y., Montero, D., Cheng, C. P., Yau, S. Y., & Siu, P. M. (2022). Comparative effectiveness of exercise, antidepressants and their combination in treating non-severe depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 56, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, R. M., Barbalace, M. C., Croce, L., Malaguti, M., Campennì, A., Rotondi, M., Cannavò, S., & Hrelia, S. (2023). Autoimmune thyroid disorders: The mediterranean diet as a protective choice. Nutrients, 15, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzatkowska, K., Uchmanowicz, I., & Wleklik, M. (2014). Wpływ czynników społeczno-demograficznych na jakość życia chorych na niedoczynność tarczycy [The impact of socio-demographic factors on quality of life among patients with hypothyroidism]. Współczesne Pielegniarstwo i Ochrona Zdrowia, 1, 14–18. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Sadowska, J., & Stawska, A. (2015). Dietoprofilaktyka chorób współtowarzyszących niedoczynności tarczycy w wybranej grupie kobiet. [Nutritional Prevention of diseases concomitant with hypothyroidism in a group of selected women]. Bromatologia i Chemia Toksykologiczna, 48, 690–700. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Sarfo, J. O., Obeng, P., Kyereh, H. K., Ansah, E. W., & Attafuah, P. Y. A. (2023). Self-determination theory and quality of life of adults with diabetes: A scoping review. Journal of Diabetes Research, 5, 341656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarris, J., O’Neil, A., Coulson, C. E., Schweitzer, I., & Berk, M. (2014). Lifestyle medicine for depression. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicka-Gutaj, N., Watt, T., Sowiński, J., Gutaj, P., Waligórska-Stachura, J., & Ruchała, M. (2015). ThyPROpl—The Polish version of the thyroid-specific quality of life questionnaire ThyPRO. Endokrynologia Polska, 66, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Seń, M., Grabowska, B., & Wójcik, J. (2020). Zachowania zdrowotne, stopień akceptacji choroby i poziom wiedzy żywieniowej osób chorych na niedoczynność tarczycy i autoimmunologiczne zapalenie tarczycy typu Hashimoto. Badanie wstępne [Pro-health behaviours and degree of disease acceptance as well as eating habits among patients with hypothyrodism and Hashimoto’s autoimmune thyroiditis]. Medycyna Ogólna i Nauki o Zdrowiu, 26, 384–389. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Siegmann, E. M., Müller, H. H. O., Luecke, C., Philipsen, A., Kornhuber, J., & Grömer, T. W. (2018). Association of depression and anxiety disorders with autoimmune thyroiditis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 75, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W., Liu, H., Jiang, Y., Li, S., Jin, Y., Yan, C., & Chen, H. (2021). Correlation between depression and quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 202, 106523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwalska, J., Łukasik, S., Cymerys, M., Suwalska, A., & Bogdański, P. (2024). Determinants of weight status and body, health and life satisfaction in young adults. Nutrients, 16, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczuko, M., Syrenicz, A., Szymkowiak, K., Przybylska, A., Szczuko, U., Pobłocki, J., & Kulpa, D. (2022). Doubtful justification of the gluten-free diet in the course of Hashimoto’s disease. Nutrients, 14, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwajkosz, K., Wawryniuk, A., Sawicka, K., Łuczyk, R., & Tomaszewski, A. (2017). Niedoczynność tarczycy jako skutek przewlekłego autoimmunologicznego zapalenia gruczołu tarczowego [Hypothyroidism caused by chronic autoimmune inflammation of the thyroid gland]. Journal of Education, Health and Sport, 7, 41–54. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W. K., & Lee, J. C. (2024). Association of fast-food intake with depressive and anxiety symptoms among young adults: A pilot study. Nutrients, 16, 3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanriverdi, A., Ozcan Kahraman, B., Ozsoy, I., Bayraktar, F., Ozgen Saydam, B., Acar, S., Ozpelit, E., Akdeniz, B., & Savci, S. (2019). Physical activity in women with subclinical hypothyroidism. Journal of Endocrinology Investigation, 42, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, A. I. (2022). Health and life satisfaction factors of Portuguese older adults. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 99, 104600. [Google Scholar]

- Thatipamala, P., Noel, J. E., & Orloff, L. (2022). Quality of life after thyroidectomy for Hashimoto disease in patients with persistent symptoms. Ear Nose & Throat Journal, 101, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L., Lu, C., & Teng, W. (2024). Association between physical activity and thyroid function in American adults: A survey from the NHANES database. BMC Public Health, 24, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülker, M. T., Çolak, G. A., Baş, M., & Erdem, M. G. (2023). Evaluation of the effect of gluten-free diet and Mediterranean diet on autoimmune system in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Food Science & Nutrition, 12, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Vancini, R. L., Rayes, A. B. R., Lira, C. A. B., Sarro, K. J., & Andrade, M. S. (2017). Pilates and aerobic training improve levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life in overweight and obese individuals. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 75, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A., Wan, X., Zhuang, P., Jia, W., Ao, Y., Liu, X., Tian, Y., Zhu, L., Huang, Y., Yao, J., Wang, B., Wu, Y., Xu, Z., Wang, J., Yao, W., Jiao, J., & Zhang, Y. (2023). High fried food consumption impacts anxiety and depression due to lipid metabolism disturbance and neuroinflammation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 120, e2221097120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D. E. R., & Bredin, S. S. D. (2017). Health benefits of physical activity: A systematic review of current systematic reviews. Current Opinion in Cardiology, 32, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOQOL-BREF. (1996). WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment. Field Trial Version. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtachnio, D., Osiewska, A., Bartoszewicz, J., Grądzik, A., Nowakowska, I., Kudan, M., Gojarek, A., & Mikrut, K. (2022). Hypothyroidism: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment. Journal of Education, Health and Sport, 12, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtas, N., Wadolowska, L., & Bandurska-Stankiewicz, E. (2019). Evaluation of qualitative dietary protocol (Diet4Hashi) application in dietary counseling in Hashimoto thyroiditis: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołowicka, L., & Jaracz, K. (2001). Jakość życia w naukach medycznych [Quality of life in medical sciences]. Uczelniane Akademii Medycznej w Poznaniu. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., Huang, H., & Yu, X. (2023). How does Hashimoto’s thyroiditis affect bone metabolism? Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, 24, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalcin, M. M., Altinova, A. E., Cavnar, B., Bolayir, B., Akturk, M., Arslan, E., Ozkan, C., Cakir, N., & Balos Toruner, F. (2017). Is thyroid autoimmunity itself associated with psychological well-being in euthyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis? Endocrinology Journal, 64, 425–429. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, H., Kim, D. W., Lee, E. J., Jung, J., & Yoo, S. (2021). Analysis of the effects of nutrient intake and dietary habits on depression in Korean adults. Nutrients, 13, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, M., Łuszczki, E., & Dereń, K. (2023). Dietary nutrient deficiencies and risk of depression (review article 2018–2023). Nutrients, 15, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Place of residence | City with above 100,000 residents | 40.4 |

| City with below 100,000 residents | 35.8 | |

| Villages | 23.8 | |

| Level of education | Higher | 77.9 |

| Secondary | 19.3 | |

| Vocational | 2.8 | |

| Body Mass Index | Normal weight BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 52.1 |

| Overweight BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 29.7 | |

| Obesity BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 12.8 | |

| Underweight BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 | 5.4 | |

| Variables | M | Me | Min | Max | Q25 | Q75 | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBI | Positive mental attitude | 21.21 | 21.00 | 10 | 29 | 19.00 | 24.00 | 3.75 |

| Preventative behaviours | 22.22 | 23.00 | 11 | 30 | 20.00 | 25.00 | 3.88 | |

| Proper eating habits | 21.62 | 22.00 | 9 | 30 | 19.00 | 25.00 | 4.58 | |

| Pro-health practices | 20.80 | 21.00 | 6 | 30 | 18.00 | 24.00 | 3.89 | |

| HBI Total | 85.85 | 87.00 | 53 | 112 | 78.00 | 93.00 | 11.30 | |

| Variables | M | Me | Min | Max | Q25 | Q75 | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWLS | 20.82 | 22.00 | 5 | 35 | 17.00 | 25.00 | 5.66 | |

| WHO-QoL | Raw results | |||||||

| WHOQOL Somatic | 20.24 | 20.00 | 11 | 30 | 18.00 | 23.00 | 3.26 | |

| WHOQoL Psychological | 20.15 | 20.00 | 9 | 27 | 18.00 | 22.00 | 3.18 | |

| WHOQoL Social | 10.71 | 11.00 | 3 | 15 | 9.00 | 13.00 | 2.66 | |

| WHOQoL Environmental | 28.37 | 29.00 | 12 | 39 | 26.00 | 31.00 | 4.65 | |

| Converted results (scale in accordance with WHOQoL-100) | ||||||||

| WHOQoL Somatic | 11.57 | 11.43 | 6.29 | 17.14 | 10.29 | 13.14 | 1.86 | |

| WHOQoL Psychological | 13.43 | 13.33 | 6.00 | 18.00 | 12.00 | 14.67 | 2.12 | |

| WHOQoL Social | 14.28 | 14.67 | 4.00 | 20.00 | 12.00 | 17.33 | 3.54 | |

| WHOQoL Environmental | 14.19 | 14.50 | 6.00 | 19.50 | 13.00 | 15.50 | 2.33 | |

| Variables | Spearman’s R | t(n − 2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive mental attitude and BDI | −0.57 | −10.24 | <0.001 |

| Preventative behaviours and BDI | −0.20 | −3.07 | 0.002 |

| Proper eating habits and BDI | −0.20 | −3.07 | 0.002 |

| Pro-health practices and BDI | −0.16 | −2.32 | 0.021 |

| HBI Total and BDI | −0.38 | −6.06 | <0.001 |

| Multiple—R | Multiple—R2 | Adjusted—R2 | df—Model | df—Residual | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 4 | 214 | 33.2 | <0.001 |

| BDI—Param. | BDI—Std.Err | BDI—t | BDI—p | BDI—Beta (ß) | BDI—St.Err.ß | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 43.06 | 3.997 | 10.8 | <0.001 | ||

| Positive mental attitude | −1.63 | 0.154 | −10.6 | <0.001 | −0.64 | 0.06 |

| Preventative behaviours | −0.00 | 0.157 | −0.0 | 0.986 | −0.00 | 0.06 |

| Proper eating habits | −0.14 | 0.132 | −1.1 | 0.279 | −0.07 | 0.06 |

| Pro-health practices | 0.31 | 0.147 | 2.1 | 0.035 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Variables | Spearman’s R | t(n − 2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive mental attitude and SWLS | 0.49 | 8.30 | <0.001 |

| Preventative behaviours and SWLS | 0.19 | 2.89 | 0.004 |

| Proper eating habits and SWLS | 0.11 | 1.62 | 0.107 |

| Pro-health practices and SWLS | 0.26 | 3.94 | <0.001 |

| HBI Total and SWLS | 0.34 | 5.27 | <0.001 |

| Multiple—R | Multiple—R2 | Adjusted—R2 | df—Model | df—Residual | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWLS | 0.56 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 4 | 214 | 24.41 | <0.001 |

| SWLS Beta (ß) | SWLS St.Err.ß | SWLS Param. | SWLS Std.Err | SWLS t | SWLS p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.83 | 2.50 | 0.73 | 0.466 | ||

| Positive mental attitude | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.76 | 0.10 | 7.85 | <0.001 |

| Preventative behaviours | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 1.14 | 0.256 |

| Proper eating habits | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.13 | 0.08 | −1.61 | 0.109 |

| Pro-health practices | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 1.76 | 0.080 |

| Variables | Spearman’s R | t(n − 2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive mental attitude and WHOQoL Somatic | 0.32 | 4.99 | <0.001 |

| Positive mental attitude and WHOQoL Psychological | 0.46 | 7.66 | <0.001 |

| Positive mental attitude and WHOQoL Social | 0.37 | 5.78 | <0.001 |

| Positive mental attitude and WHOQoL Environmental | 0.29 | 4.43 | <0.001 |

| Preventative behaviours and WHOQoL Somatic | 0.20 | 2.98 | 0.003 |

| Preventative behaviours and WHOQoL Psychological | 0.24 | 3.61 | <0.001 |

| Preventative behaviours and WHOQoL Social | 0.19 | 2.87 | 0.005 |

| Preventative behaviours and WHOQ_ Environmental | 0.16 | 2.35 | 0.02 |

| Proper eating habits and WHOQoL Somatic | 0.38 | 5.99 | <0.001 |

| Proper eating habits and WHOQoL Psychological | 0.20 | 3.00 | 0.003 |

| Proper eating habits and WHOQoL Social | 0.06 | 0.87 | 0.387 |

| Proper eating habits and WHOQoL Environmental | 0.10 | 1.45 | 0.148 |

| Pro-health practices and WHOQoL Somatic | 0.18 | 2.76 | 0.006 |

| Pro-health practices and WHOQoL Psychological | 0.15 | 2.31 | 0.022 |

| Pro-health practices and WHOQoL Social | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.451 |

| Pro-health practices and WHOQoL Environmental | 0.12 | 1.85 | 0.066 |

| HBI Total and WHOQoL Somatic | 0.39 | 6.32 | <0.001 |

| HBI Total and WHOQoL Psychological | 0.37 | 5.88 | <0.001 |

| HBI Total and WHOQoL Social | 0.22 | 3.28 | 0.001 |

| HBI Total and WHOQoL Environmental | 0.22 | 3.36 | 0.001 |

| WHOQoL | Multiple—R | Multiple—R2 | Adjusted—R2 | df—Model | df—Residual | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic | 0.44 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 4 | 214 | 12.74 | <0.001 |

| Psychological | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 4 | 214 | 21.00 | <0.001 |

| Social | 0.44 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 4 | 214 | 12.76 | <0.001 |

| Environmental | 0.34 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 4 | 214 | 7.13 | <0.001 |

| WHOQoL Somatic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (ß) | St.Err.ß | Param. | Std.Err | t | p | |

| Intercept | 11.07 | 1.56 | 7.08 | <0.001 | ||

| Positive mental attitude | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 4.02 | <0.001 |

| Preventative behaviours | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.66 | 0.507 |

| Proper eating habits | 0.31 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 4.27 | <0.001 |

| Pro-health practices | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.861 |

| WHOQoL Psychological | ||||||

| Beta (ß) | St.Err.ß | Param. | Std.Err | t | p | |

| Intercept | 9.74 | 1.43 | 6.79 | <0.001 | ||

| Positive mental attitude | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 7.62 | <0.001 |

| Preventative behaviours | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1.17 | 0.244 |

| Proper eating habits | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.14 | 0.889 |

| Pro-health practices | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.882 |

| WHOQoL Social | ||||||

| Beta (ß) | St.Err.ß | Param. | Std.Err | t | p | |

| Intercept | 4.50 | 1.27 | 3.53 | 0.001 | ||

| Positive mental attitude | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 6.14 | <0.001 |

| Preventative behaviours | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.61 | 0.108 |

| Proper eating habits | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.85 | 0.397 |

| Pro-health practices | −0.08 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.23 | 0.220 |

| WHOQoL Environmental | ||||||

| Beta (ß) | St.Err.ß | Param. | Std.Err | t | p | |

| Intercept | 19.29 | 2.33 | 8.28 | <0.001 | ||

| Positive mental attitude | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 4.69 | <0.001 |

| Preventative behaviours | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.54 | 0.592 |

| Proper eating habits | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.13 | 0.897 |

| Pro-health practices | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.40 | 0.687 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gacek, M.; Wojtowicz, A.; Kędzior, J. Pro-Health Behaviours and Depressive Symptoms as Well as Satisfaction with and Quality of Life Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060097

Gacek M, Wojtowicz A, Kędzior J. Pro-Health Behaviours and Depressive Symptoms as Well as Satisfaction with and Quality of Life Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(6):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060097

Chicago/Turabian StyleGacek, Maria, Agnieszka Wojtowicz, and Jolanta Kędzior. 2025. "Pro-Health Behaviours and Depressive Symptoms as Well as Satisfaction with and Quality of Life Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 6: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060097

APA StyleGacek, M., Wojtowicz, A., & Kędzior, J. (2025). Pro-Health Behaviours and Depressive Symptoms as Well as Satisfaction with and Quality of Life Among Women with Hashimoto’s Disease. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(6), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060097