Development and Psychometric Testing of Perfectionism Inventory to Assess Perfectionism and Academic Stress in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Centre Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Instrument Development

2.2.1. Conceptualization and Item Development

2.2.2. Item Revision

2.2.3. Content Validity

2.2.4. Pilot Testing

2.2.5. Instrument

2.2.6. Setting and Sampling

2.2.7. Data Collection for Final Validation

2.2.8. Data Analysis

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

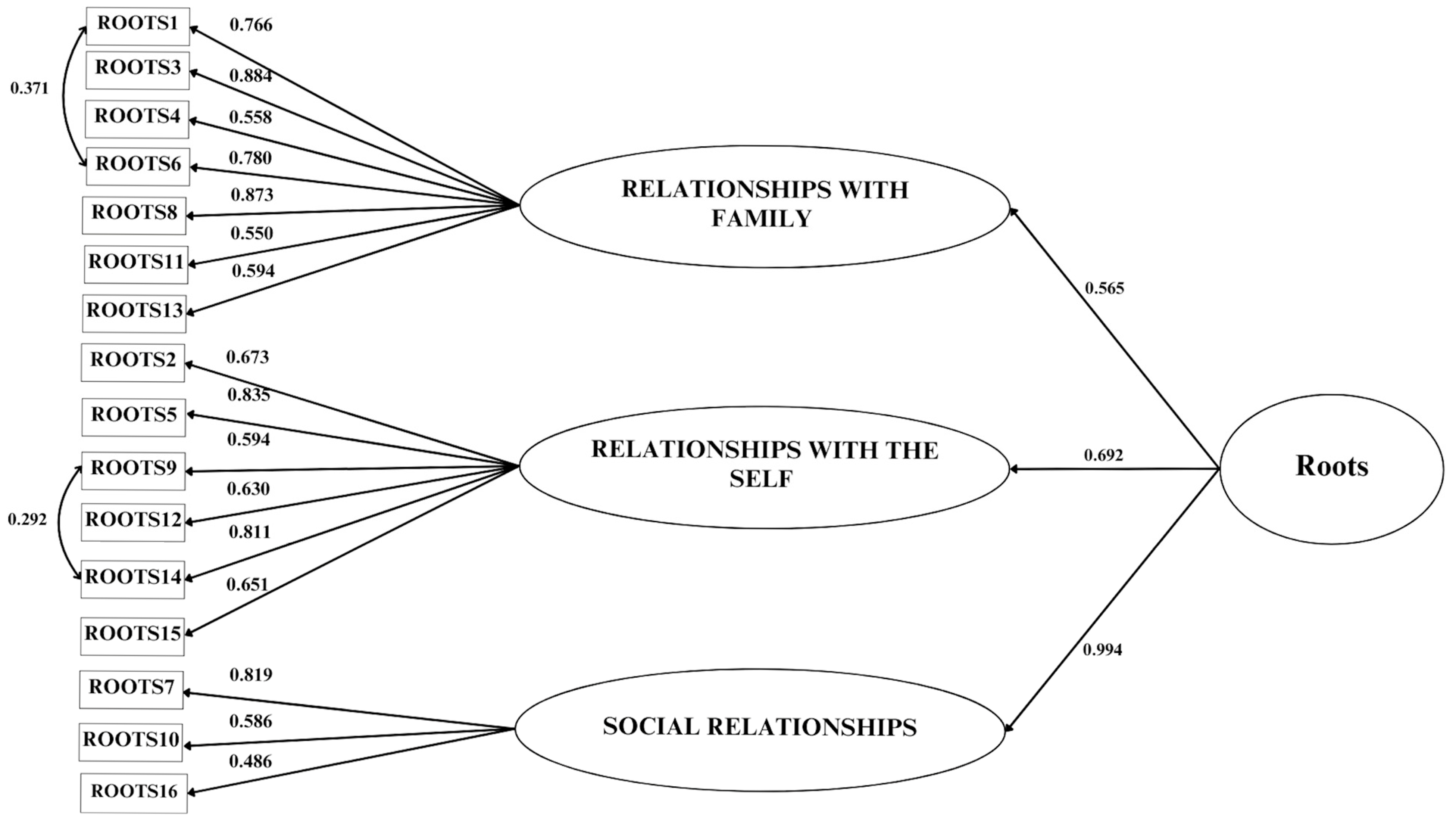

3.2. Structural Validity

3.3. Construct Validity

3.4. Reliability

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policy and Practice

4.2. Strength and Limitations of the Study

4.3. Recommendations for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Apicella, C., Norenzayan, A., & Henrich, J. (2020). Beyond WEIRD: A review of the last decade and a look ahead to the global laboratory of the future. Evolution and Human Behavior, 41(5), 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaag, R., Sumodevilla, J. L., & Potane, J. (2024). Factors affecting student drop out behavior: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Management and Innovation, 5(1), 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N., & Bilgel, N. (2008). The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(8), 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedewy, D., & Gabriel, A. (2015). Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: The Perception of Academic Stress Scale. Health Psychology Open, 2(2), 2055102915596714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiter, R., Nash, R., McCrady, M., Rhoades, D., Linscomb, M., Clarahan, M., & Sammut, S. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M., & Hu, L. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Bewick, B., Koutsopoulou, G., Miles, J., Slaa, E., & Barkham, M. (2010). Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well-being as they progress through university. Studies in Higher Education, 35(6), 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasberg, J. S., Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., & Chen, C. (2016). The importance of item wording: The distinction between measuring high standards versus measuring perfectionism and why it matters. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(7), 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancato, G., Macchia, S., Murgia, M., Signore, M., Simeoni, G., Blanke, K., Korner, T., Nimmergut, A., Lima, P., Paulino, R., & Jürgen, H.-Z. (2006). Handbook of recommended practices for questionnarie development and testing in European statistical systems. European Statistical System. Available online: https://www.istat.it/en/files/2013/12/Handbook_questionnaire_development_2006.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2015). Preoccupied attachment, need to belong, shame, and interpersonal perfectionism: An investigation of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collishaw, S., & Sellers, R. (2020). Trends in child and adolescent mental health prevalence, outcomes, and inequalities. In E. Taylor, F. Verhulst, J. C. M. Wong, & K. Yoshida (Eds.), Mental health and illness of children and adolescents (pp. 63–73). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T., & Hill, A. P. (2019). Perfectionism is increasing over time: A meta-analysis of birth cohort differences from 1989 to 2016. Psychological Bulletin, 145(4), 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, T., & Hill, A. P. (2022). Young people’s perceptions of their parents’ expectations and criticism are increasing over time: Implications for perfectionism. Psychological Bulletin, 148(1–2), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denovan, A., Dagnall, N., Dhingra, K., & Grogan, S. (2017). Evaluating the perceived stress scale among UK university students: Implications for stress measurement and management. Studies in Higher Education, 44, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enns, M. W., Cox, B. J., & Clara, I. (2002). Adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism: Developmental origins and association with depression proneness. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(6), 921–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E. R., Aragão, R. G., Reis, J. d. F. M., Reis, G. E. N., Santana, F. F., Alves, M. N. T., Macêdo, J. C. B., Feitosa, U. N. S., Peixoto, C. U., Martins, M. E. P., Neto, J. L. d. A., & Neto, M. L. R. (2015). Suicide in the world: An overview of prevalence and its risk factors. International Archives of Medicine, 8(186), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippello, P., Buzzai, C., Messina, G., Mafodda, A. V., & Sorrenti, L. (2020). School refusal in students with low academic performances and specific learning disorder. The role of self-esteem and perceived parental psychological control. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 67(6), 592–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2015). Measures of perfectionism. In Measures of personality and social psychological constructs (pp. 595–618). Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2020). Reflections on three decades of research on multidimensional perfectionism: An introduction to the special issue on further advances in the assessment of perfectionism. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 38(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Besser, A., Su, C., Vaillancourt, T., Boucher, D., Munro, Y., Davidson, L. A., & Gale, O. (2016). The child–adolescent perfectionism scale: Development, psychometric properties, and associations with stress, distress, and psychiatric symptoms. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(7), 634–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G. L., Panico, T., & Hewitt, P. L. (2011). Perfectionism, type a behavior, and self-efficacy in depression and health symptoms among adolescents. Current Psychology, 30(2), 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, P., Schellenberg, B. J. I., Gareau, A., Kljajic, K., & Manoni-Millar, S. (2022). Because excellencism is more than good enough: On the need to distinguish the pursuit of excellence from the pursuit of perfection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 122(6), 1117–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Mikail, S. F. (2017). Perfectionism: A relational approach to conceptualization, assessment, and treatment (pp. xv, 336). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Turnbull-Donovan, W., & Mikail, S. F. (1991). The multidimensional perfectionism scale: Reliability, validity, and psychometric properties in psychiatric samples. Psychological Assessment, 3(3), 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiçdurmaz, D., & Aydin, A. (2017). The relationship between self-compassion and multidimensional perfectionism levels and influencing factors in nursing students. Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 8(2), 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R. H. (1995). The structural equation modeling approach: Basic concepts and fundamental issues. In Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 1–15). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, C. S., Baranik, L. E., & Daniel, F. (2013). College student stressors: A review of the qualitative research. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 29(4), 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M., Altaf, S., & Kausar, H. (2013). Effect of perceived academic stress on students’ performance. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 7(2), 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, A., Hewitt, P., Cox, D., Flett, G., & Chen, C. (2019). Adverse parenting and perfectionism: A test of the mediating effects of attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, and perceived defectiveness. Personality and Individual Differences, 150, 109474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L. E., Rinn, A. N., Crutchfield, K., Ottwein, J. K., Hodges, J., & Mun, R. U. (2021). Perfectionism and the imposter phenomenon in academically talented undergraduates. Gifted Child Quarterly, 65(3), 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limburg, K., Watson, H. J., Hagger, M. S., & Egan, S. J. (2017). The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(10), 1301–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y. M., & Chen, F. S. (2009). Academic stress inventory of students at universities and colleges of technology. World Transactions on Engineering and Technology Education, 7, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X., Ping, S., & Gao, W. (2019). Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well-being as they experience university life. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(16), 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, C., Novara, C., Mallia, L., Pastore, M., & Vacca, M. (2022). The short forms of the hewitt and flett’s multidimensional perfectionism scale: Which factor structure better fits Italian data? Journal of Personality Assessment, 104(1), 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, S., Gunnell, D., Cooper, C., Bebbington, P. E., Howard, L. M., Brugha, T., Jenkins, R., Hassiotis, A., Weich, S., & Appleby, L. (2019). Prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm and service contact in England, 2000–14: Repeated cross-sectional surveys of the general population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(7), 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondo, M., Sechi, C., & Cabras, C. (2021). Psychometric evaluation of three versions of the Italian perceived stress scale. Current Psychology, 40(4), 1884–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Osenk, I., Williamson, P., & Wade, T. D. (2020). Does perfectionism or pursuit of excellence contribute to successful learning? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Assessment, 32(10), 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M. C., Hetrick, S. E., & Parker, A. G. (2020). The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, H., Firebaugh, C. M., Zolnikov, T. R., Wardlow, R., Morgan, S. M., & Gordon, B. (2021). A systematic review on the psychological effects of perfectionism and accompanying treatment. Psychology, 12(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M. J., & Chang, E. C. (2015). Ethnic variations between Asian and European Americans in interpersonal sources of socially prescribed perfectionism: It’s not just about parents! Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6(1), 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T., & Owen, S. V. (2007). Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2010). Introduction to psychometric theory. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regehr, C., Glancy, D., & Pitts, A. (2013). Interventions to reduce stress in university students: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 148(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revelle, W., & Zinbarg, R. E. (2009). Coefficients alpha, beta, omega, and the glb: Comments on Sijtsma. Psychometrika, 74(1), 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, K. G., Richardson, C. M. E., & Ray, M. E. (2016). Perfectionism in academic settings. In F. M. Sirois, & D. S. Molnar (Eds.), Perfectionism, health, and well-being (pp. 245–264). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, S.-S. (2017). Factors related to taiwanese adolescents’ academic procrastination, time management, and perfectionism. Journal of Educational Research, 110(4), 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sironic, A., & Reeve, R. A. (2015). A combined analysis of the frost multidimensional perfectionism scale (fmps), child and adolescent perfectionism scale (CAPS), and almost perfect scale—Revised (APS-R): Different perfectionist profiles in adolescent high school students. Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, P. D., & Owens, R. G. (1998). A dual process model of perfectionism based on reinforcement theory. Behavior Modification, 22(3), 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaney, R. B., Rice, K. G., Mobley, M., Trippi, J., & Ashby, J. S. (2001). The revised almost perfect scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M., Sherry, S., Chen, S., Saklofske, D., Mushquash, C., Flett, G., & Hewitt, P. (2018). The perniciousness of perfectionism: A meta-analytic review of the perfectionism-suicide relationship. Journal of Personality, 86, 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stairs, A. M., Smith, G. T., Zapolski, T. C. B., Combs, J. L., & Settles, R. E. (2012). Clarifying the construct of perfectionism. Assessment, 19(2), 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallman, H. M., & Hurst, C. P. (2016). The university stress scale: Measuring domains and extent of stress in university students. Australian Psychologist, 51(2), 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J. (2014). How other-oriented perfectionism differs from self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36(2), 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J. (2015). How other-oriented perfectionism differs from self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism: Further findings. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 37(4), 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, H., Gnilka, P. B., & Rice, K. G. (2017). Perfectionism and well-being: A positive psychology framework. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidic, Z., & Cherup, N. (2019). Mindfulness in classroom: Effect of a mindfulness-based relaxation class on college students’ stress, resilience, self-efficacy and perfectionism. College Student Journal, 53(1), 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., Vandenbroucke, J. P., & STROBE Initiative. (2014). The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. International Journal of Surgery, 12(12), 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. T., Permyakova, T. M., Sheveleva, M. S., & Camp, E. E. (2018). Perfectionism as a predictor of anxiety in foreign language classrooms among Russian college students. Journal of Educational, Cultural and Psychological Studies (ECPS Journal), 18, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Tao, H., Bowers, B. J., Brown, R., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Influence of social support and self-efficacy on resilience of early career registered nurses. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 40(5), 648–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, S. R. (2023). Clinical stress and clinical performance in prelicensure nursing students: A systematic review. Journal of Nursing Education, 62(1), 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. (2024). WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical principles for medical research involving human participants 2024. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Xie, D., Leong, F. T. L., & Feng, S. (2008). Culture-specific personality correlates of anxiety among Chinese and Caucasian college students. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 11(2), 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Wang, Z., Song, J., Lu, J., Huang, X., Zou, Z., & Pan, L. (2020). The positive and negative rumination scale: Development and preliminary validation. Current Psychology, 39(2), 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinbarg, R. E., Yovel, I., Revelle, W., & McDonald, R. P. (2006). Estimating generalizability to a latent variable common to all of a scale’s indicators: A comparison of estimators for ωh. Applied Psychological Measurement, 30, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (years) Mean, SD (range) | 25.19, 6.36 (18–57) | |

| n | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 338 | 72.07 |

| Male | 131 | 27.93 |

| Education | ||

| Bachelor | 338 | 72.07 |

| Master’s degree | 131 | 27.93 |

| Bachelor course year | ||

| 1st year | 83 | 17.69 |

| 2nd year | 176 | 37.52 |

| 3rd year | 93 | 19.82 |

| Master’s course year | ||

| 1st year | 40 | 8.52 |

| 2nd year | 48 | 10.23 |

| 3rd year | 29 | 6.18 |

| Type of university course | ||

| Nursing | 159 | 33.90 |

| Engineering | 48 | 10.23 |

| Medicine | 37 | 7.88 |

| Business and Economics | 29 | 6.18 |

| Psychology | 30 | 6.39 |

| Social Sciences | 29 | 6.18 |

| Sciences and Technology | 26 | 5.54 |

| Literature and Philosophy | 24 | 5.11 |

| Biology | 21 | 4.47 |

| Health Professions | 20 | 4.26 |

| Education | 18 | 3.84 |

| Law | 16 | 3.41 |

| Communication | 7 | 1.49 |

| Others | 5 | 1.07 |

| Region | ||

| Lazio | 323 | 68.87 |

| Sicily | 63 | 13.43 |

| Piedmont | 56 | 11.94 |

| Apulia | 12 | 2.56 |

| Campania | 10 | 2.13 |

| Other | 5 | 1.07 |

| Item | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roots | ||||

| Roots1. I perceived myself as receiving love from my parents. | 5.75 | 1.49 | −1.25 | 1.07 |

| Roots2. When I make a mistake, I believe that I am at fault. | 3.16 | 1.72 | 0.62 | −0.41 |

| Roots3. I feel accepted by my parents as I am. | 5.30 | 1.73 | −0.97 | 0.10 |

| Roots4. I believe that my opinion is important to my family. | 4.93 | 1.57 | −0.64 | −0.05 |

| Roots5. No matter what I do, I feel inadequate. | 4.36 | 1.97 | −0.19 | −1.14 |

| Roots6. I trust my parents. | 5.56 | 1.65 | −1.22 | 0.78 |

| Roots7. I feel accepted by others as I am. | 4.52 | 1.64 | −0.43 | −0.62 |

| Roots8. I believe that my parents trust me. | 5.61 | 1.49 | −1.18 | 1.07 |

| Roots9. I am afraid of failing. | 2.26 | 1.53 | 1.34 | 1.40 |

| Roots10. I feel trusted by others. | 5.36 | 1.23 | −0.76 | 0.89 |

| Roots11. My parents have given me the freedom to choose in important matters. | 5.73 | 1.48 | −1.29 | 1.19 |

| Roots12. I belief I am worthy as a person, regardless of my mistakes. | 5.75 | 1.38 | −1.41 | 2.24 |

| Roots13. My parents are satisfied with my achievements based on my efforts. | 5.41 | 1.48 | −1.03 | 0.77 |

| Roots14. When I make a mistake, I feel like a failure. | 3.30 | 1.94 | 0.50 | −0.83 |

| Roots15. I feel like I don’t have much to be proud of. | 4.42 | 1.94 | −0.22 | −1.14 |

| Roots16. I feel I can trust others. | 3.89 | 1.57 | −0.17 | −0.72 |

| MPS-R | ||||

| MPS1. When I am working on something, I cannot relax until it is perfect | 5.16 | 1.41 | −0.75 | 0.38 |

| MPS2. I find it difficult to meet others’ expectations of me. | 4.21 | 1.74 | −0.18 | −0.91 |

| MPS3. One of my goals is to be perfect in everything I do. | 4.64 | 1.72 | −0.60 | −0.48 |

| MPS4. Everything that others do must be of top-notch quality. | 3.22 | 1.52 | 0.13 | −0.73 |

| MPS5. I feel that people are too demanding of me. | 4.39 | 1.75 | −0.34 | −0.73 |

| MPS6. It makes me uneasy to see an error in my work. | 5.71 | 1.19 | −0.90 | 0.90 |

| MPS7. I cannot stand to see people close to me make mistakes. | 3.13 | 1.59 | 0.21 | −0.91 |

| MPS8. The people around me expect me to succeed at everything I do | 4.61 | 1.73 | −0.46 | −0.63 |

| MPS9. I do not have to be the best at whatever I am doing. | 3.51 | 1.78 | 0.21 | −0.94 |

| MPS10. I have high expectations for the people who are important to me. | 4.56 | 1.48 | −0.51 | 0.03 |

| MPS11. My family expects me to be perfect. | 3.71 | 1.87 | 0.01 | −1.08 |

| MPS12. I set very high standards for myself | 5.58 | 1.46 | −1.10 | 0.90 |

| MPS13. The people who matter to me should never let me down | 4.74 | 1.58 | −0.48 | −0.28 |

| MPS14. Success means that I work even harder to please others | 3.06 | 1.92 | 0.54 | −0.87 |

| IPSS-R | ||||

| In the last month, how often have you (been/felt): | ||||

| IPSS1. Upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? | 1.65 | 1.06 | 0.18 | −0.49 |

| IPSS2. Unable to control the important things in your life? | 1.77 | 1.08 | 0.01 | −0.59 |

| IPSS3. Nervous and “stressed”? | 3.09 | 0.88 | −0.86 | 0.46 |

| IPSS4. Could not cope with all the things that you had to do? | 2.47 | 1.08 | −0.34 | −0.49 |

| IPSS5. Angered because of things that were outside your control? | 2.38 | 1.14 | −0.26 | −0.59 |

| IPSS6. Difficulties were piling up so that you could not overcome them? | 1.77 | 1.22 | 0.17 | −0.81 |

| IPSS7. Confident about your ability to handle your personal problems? | 1.59 | 0.95 | 0.24 | −0.39 |

| IPSS8. Things were going your way? | 2.12 | 0.93 | 0.11 | −0.14 |

| IPSS9. Dealt successfully with irritating life hassles? | 1.94 | 0.90 | 0.10 | −0.01 |

| IPSS10. You were on top of things? | 2.16 | 0.97 | 0.03 | −0.43 |

| IPSS11. Pressured by the standards imposed by the institution (school/university)? | 2.73 | 1.17 | −0.64 | −0.41 |

| IPSS12. Strongly pressured by teachers regarding your performance? | 1.60 | 1.35 | 0.36 | −1.05 |

| IPSS13. Competition with classmates about grades was very intense? | 1.30 | 1.37 | 0.69 | −0.82 |

| IPSS14. Strongly pressured by your family about your grades? | 1.18 | 1.37 | 0.78 | −0.75 |

| IPSS15. Your university experience caused you more stress than you could usually handle? | 2.41 | 1.26 | −0.30 | −0.96 |

| Mean | SD | ꙍ | ICC | FSD | Fam | Self | Soc | Roots | SOP | OOP | SPP | MPS-R | Stress | Coping | Acad | IPSS-R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fam | 5.47 | 1.19 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Self | 3.87 | 1.34 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.33 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Soc | 4.59 | 1.15 | 0.67 | 0.85 | 0.44 ** | 0.50 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Roots | 4.71 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.80 ** | 0.80 ** | 0.71 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| SOP | 4.92 | 1.09 | 0.77 | 0.90 | −0.03 | −0.36 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.24 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| OOP | 3.91 | 1.09 | 0.67 | 0.86 | −0.00 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.28 ** | 1 | |||||||

| SPP | 4.00 | 1.31 | 0.79 | 0.91 | −0.28 ** | −0.56 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.50 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.25 ** | 1 | ||||||

| MPS-R | 4.30 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.58 | 0.80 | −0.16 ** | −0.48 ** | −0.26 ** | −0.39 ** | 0.78 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.81 ** | 1 | ||||

| Stress | 2.19 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.93 | −0.20 ** | −0.50 ** | −0.26 ** | −0.42 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.02 | 0.37 ** | 0.31 ** | 1 | ||||

| Coping | 1.96 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.91 | −0.23 ** | −0.54 ** | −0.38 ** | −0.49 ** | 0.14 ** | −0.04 | 0.33 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.56 ** | 1 | |||

| Acad | 1.84 | 0.95 | 0.79 | 0.87 | −0.18 ** | −0.44 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.38 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.10 * | 0.53 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.26 ** | 1 | ||

| IPSS-R | 2.01 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.86 | −0.25 ** | −0.61 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.52 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.05 | 0.53 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.88 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.80 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piredda, M.; Lo Cascio, A.; Marchetti, A.; Campanozzi, L.; Pellegrino, P.; Mondo, M.; Petrucci, G.; Latina, R.; De Maria, M.; Alvaro, R.; et al. Development and Psychometric Testing of Perfectionism Inventory to Assess Perfectionism and Academic Stress in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Centre Study. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060094

Piredda M, Lo Cascio A, Marchetti A, Campanozzi L, Pellegrino P, Mondo M, Petrucci G, Latina R, De Maria M, Alvaro R, et al. Development and Psychometric Testing of Perfectionism Inventory to Assess Perfectionism and Academic Stress in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Centre Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(6):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060094

Chicago/Turabian StylePiredda, Michela, Alessio Lo Cascio, Anna Marchetti, Laura Campanozzi, Paolo Pellegrino, Marina Mondo, Giorgia Petrucci, Roberto Latina, Maddalena De Maria, Rosaria Alvaro, and et al. 2025. "Development and Psychometric Testing of Perfectionism Inventory to Assess Perfectionism and Academic Stress in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Centre Study" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 6: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060094

APA StylePiredda, M., Lo Cascio, A., Marchetti, A., Campanozzi, L., Pellegrino, P., Mondo, M., Petrucci, G., Latina, R., De Maria, M., Alvaro, R., & De Marinis, M. G. (2025). Development and Psychometric Testing of Perfectionism Inventory to Assess Perfectionism and Academic Stress in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Centre Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(6), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060094