Perceived Stigma and Quality of Life in Binary and Nonbinary/Queer Transgender Individuals in Italy: The Mediating Roles of Patient–Provider Relationship Quality and Barriers to Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics

2.2.2. Perceived Stigma

2.2.3. Patient–Provider Relationship Quality and Barriers to Care

2.2.4. Quality of Life

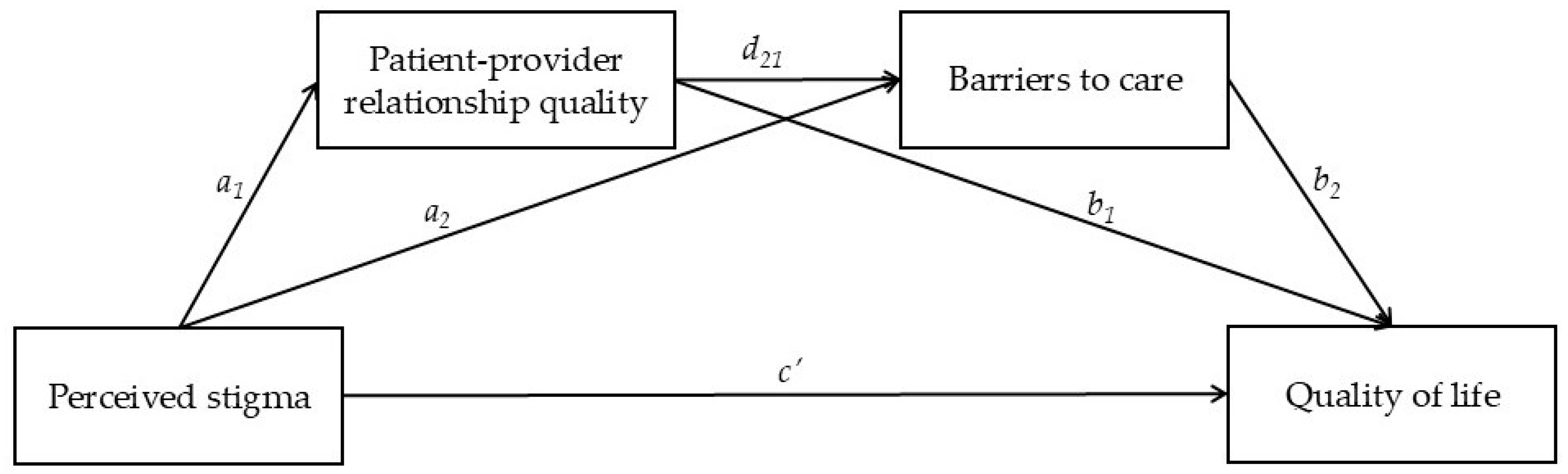

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

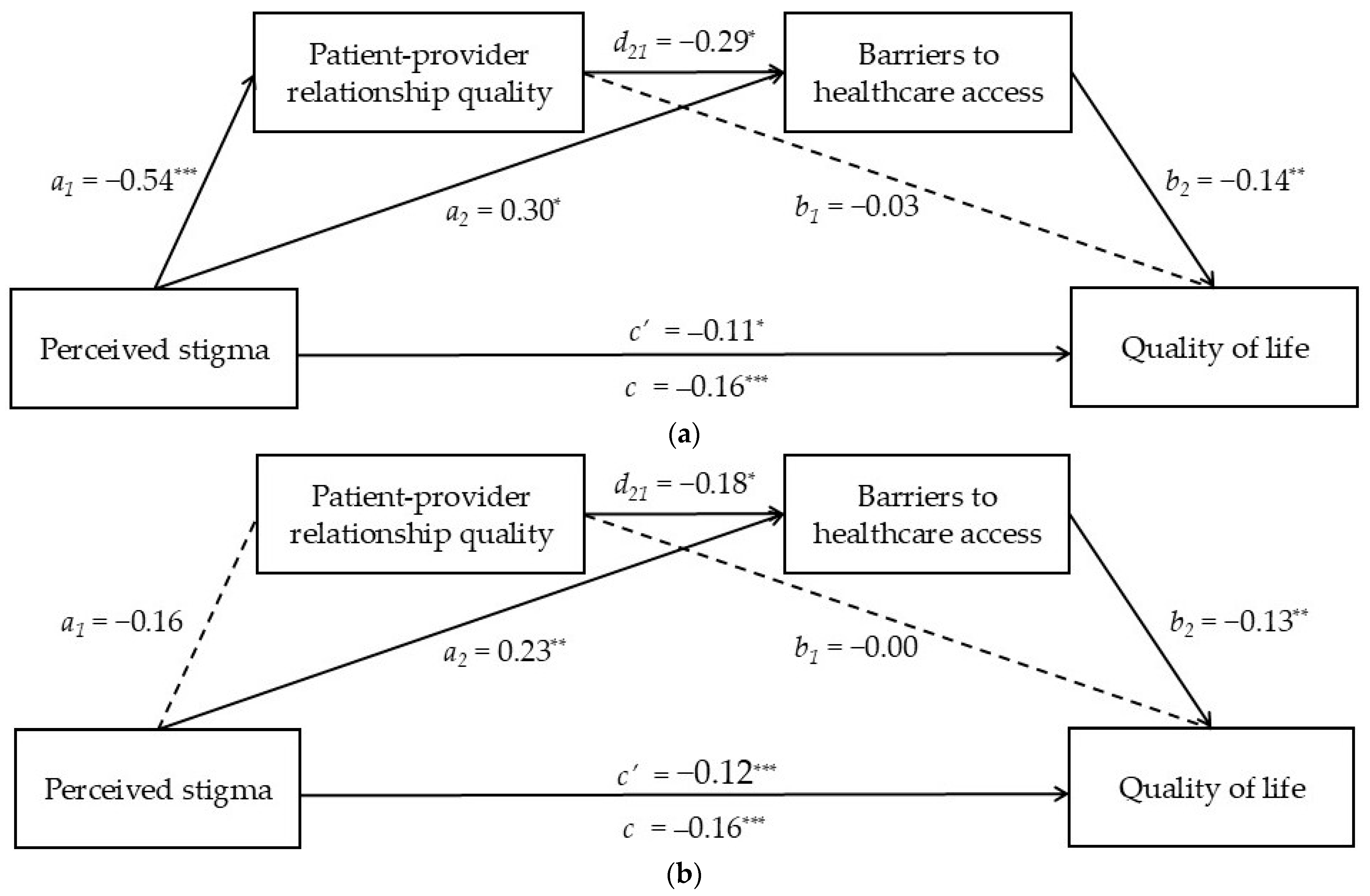

3.3. Direct and Indirect Associations Between Perceived Stigma and Quality of Life Through Patient–Provider Relationship Quality and Barriers to Care

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Clinical Implications and Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afzal, M., Rizvi, F., Azad, A. H., Rajput, A. M., Khan, A., & Tariq, N. (2014). Effect of demographic characteristics on patient’s satisfaction with health care facility. Journal of Postgraduate Medical Institute, 28(2), 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Amarante, I. C. J., Lippman, S. A., Sevelius, J. M., Saggese, G. S. R., da Silva, A. A. M., & Veras, M. A. S. M. (2024). Anticipated stigma and social barriers to communication between transgender women newly diagnosed with HIV and health care providers: A mediation analysis. LGBT Health, 11(3), 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S. R., Tambling, R., Yorgason, J. B., & Rackham, E. (2019). The mediating role of the therapeutic alliance in understanding early discontinuance. Psychotherapy Research, 29(7), 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzani, A., Siboni, L., Lindley, L., Paz Galupo, M., & Prunas, A. (2024). From abstinence to deviance: Sexual stereotypes associated with transgender and nonbinary individuals. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 21, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, E. (2019). Integration challenges faced by transgender refugees in Italy. In A. Güler, M. Shevtsova, & D. Venturi (Eds.), LGBTI asylum seekers and refugees from a legal and political perspective. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beek, T. F., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Kreukels, B. P. (2016). Gender incongruence/gender dysphoria and its classification history. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrian, K., Exsted, M. D., Lampe, N. M., Pease, S. L., & Akré, E. L. (2025). Barriers to quality healthcare among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Health Services Research, 60(1), e14362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochicchio, V., Mezzalira, S., Walls, E., Méndez, L. P., López-Sáez, M. Á., Bodroža, B., Ellul, M. J., & Scandurra, C. (2024). Affective and attitudinal features of benevolent heterosexism in Italy: The Italian validation of the Multidimensional Heterosexism Inventory. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 21(3), 921–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourelly, R., Lorusso, M., & Mariotto, M. (2024). Trans students in Italian schools: Challenges and best practices. European Journal of Volunteering and Community-Based Projects, 1(1), 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower-Brown, S., Zadeh, S., & Jadva, V. (2023). Binary-trans, non-binary and gender-questioning adolescents’ experiences in UK schools. Journal of LGBT Youth, 20(1), 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, T. L., Sequeira, G. M., Egan, J. E., Ray, K. N., Miller, E., & Coulter, R. W. S. (2022). Binary and nonbinary transgender adolescents’ healthcare experiences, avoidance, and well visits. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 71(4), 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, N. J., & Catalpa, J. M. (2019). Social and psychological heterogeneity among binary transgender, non-binary transgender and cisgender individuals. Psychology & Sexuality, 10(1), 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, N. J., & Syed, M. (2019). Transnormativity and transgender identity development: A master narrative approach. Sex Roles, 81, 306325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carone, N., Innocenzi, E., & Lingiardi, V. (2025). Microaggressions and dropout when working with sexual minority parents in clinical settings: The working alliance as a mediating mechanism. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 12(1), 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalpa, J. M., McGuire, J. K., Fish, J. N., Nic Rider, G., Bradford, N., & Berg, D. (2019). Predictive validity of the Genderqueer Identity Scale (GQI): Differences between genderqueer, transgender and cisgender sexual minority individuals. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesconetto Coswosck, K. H., Marques-Rocha, J. L., Moreira, J. A., Guandalini, V. R., & Lopes-Júnior, L. C. (2023). Quality of life of transgender people under the lens of social determinants of health: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open, 13(7), e067575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B. A., Veale, J. F., Townsend, M., Frohard-Dourlent, H., & Saewyc, E. (2018). Non-binary youth: Access to gender-affirming primary health care. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(2), 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D., & Rotundo, A. (2024). The experience of transgender people in the Italian healthcare context: A qualitative study. International Journal of Gender Studies, 13, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G., Marinacci, C., Caiazzo, A., & Spadea, T. (2003). Individual and contextual determinants of inequalities in health: The Italian case. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 33(4), 635–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruciani, G., Quintigliano, M., Mezzalira, S., Scandurra, C., & Carone, N. (2024). Attitudes and knowledge of mental health practitioners towards LGBTQ+ patients: A mixed-method systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 113, 102488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Pelle, C., Cerratti, F., Di Giovanni, P., Cipollone, F., & Cicolini, G. (2018). Attitudes towards and knowledge about lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients among Italian nurses: An observational study. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 50, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, I. J., Strauss, P., Winter, S., & Lin, A. (2020). Misgendering and experiences of stigma in health care settings for transgender people. The Medical Journal of Australia, 212(4), 150–151.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EuroQol Research Foundation. (2019). EQ-5D-5L User Guide Version 3.0: Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-5L instrument. Available online: https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Falck, F., & Bränström, R. (2023). The significance of structural stigma towards transgender people in health care encounters across Europe: Health care access, gender identity disclosure, and discrimination in health care as a function of national legislation and public attitudes. BMC Public Health, 23, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feo, F. (2022). Legislative reforms to fight discrimination and violence against LGBTQ+: The failure of the Zan Bill in Italy. European Journal of Politics and Gender, 5(1), 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, F., De Belvis, A. G., Valerio, L., Longhi, S., Lazzari, A., Fattore, G., Ricciardi, W., & Maresso, A. (2014). Italy: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 16(4), 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Fiani, C. N., & Han, H. J. (2019). Navigating identity: Experiences of binary and nonbinary transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) adults. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Simoni, J. M., Kim, H.-J., Lehavot, K., Walters, K. L., Yang, J., Hoy-Ellis, C. P., & Muraco, A. (2014). The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohard-Dourlent, H., Dobson, S., Clark, D. B. A., Doull, M., & Saewyc, E. M. (2017). “I would have preferred more options”: Accounting for non-binary youth in health research. Nursing Inquiry, 24, e12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2023). Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Current Opinion in Psychology, 51, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A. E., Kuvalanka, K. A., Budge, S. L., Benz, M. B., & Smith, J. Z. (2019). Health care experiences of transgender binary and nonbinary university students. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(1), 59–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, T., Reisner, S. L., Harper, G. W., Gamarel, K. E., & Stephenson, R. (2020). State policies and healthcare use among transgender people in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(2), 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, D. C., Parra, L. A., & Goldbach, J. T. (2022). Access to health services among sexual minority people in the United States. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30, e4770–e4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Link, B. G. (2014). Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C., & Paradise, J. (2008). Health insurance and access to health care in the United States. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILGA (International Lesbian Gay Bisexual Trans and Intersex Association). (2024). ILGA Europe rainbow index 2024. Available online: https://rainbowmap.ilga-europe.org/ (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. Available online: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Johnson, A. H. (2016). Transnormativity: A new concept and its validation through documentary film about transgender men. Sociological Inquiry, 86(4), 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattari, S. K., Bakko, M., Hecht, H. K., & Kattari, L. (2019). Correlations between healthcare provider interactions and mental health among transgender and nonbinary adults. SSM—Population Health, 10, 100525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W. M., White Hughto, J. M., & Operario, D. (2020). Transgender stigma: A critical scoping review of definitions, domains, and measures used in empirical research. Social Science & Medicine, 250, 112867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe-Duncan, A., Logie, C. H., Newman, P. A., Bauer, G. R., & Kazemi, M. (2020). A qualitative study of resilience among transgender women living with HIV in response to stigma in healthcare. AIDS Care, 32(8), 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A. G., Miceli, R., Trapani, D., Massagrande, M., Morano, F., Marsoni, S., La Verde, N., Berardi, R., Casolino, R., Lambertini, M., Dalu, D., Di Maio, M., Beretta, G. D., Perrone, F., Cinieri, S., & Pietrantonio, F. (2023). Cancer care in transgender and gender-diverse persons: Results from two national surveys among providers and health service users by the Italian Association of Medical Oncology. ESMO Open, 8(3), 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B. G. (1987). Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review, 52(1), 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manulik, S., Karniej, P., & Rosińczuk, J. (2018). The influence of socio-demographic characteristics on respondents’ perceptions of healthcare service quality. Journal of Education, Health and Sport, 8(12), 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, M., Brogonzoli, L., Ruocco, A., Sala, E., D’Arienzo, S., Manoli, M., Pagano, M. T., Fisher, A. D., Iardino, R., Pedale, R., Grattagliano, I., Cricelli, C., & Pierdominici, M. (2024). Examining the training needs and perspectives of Italian general practitioners on transgender and gender diverse healthcare: Insights from a national survey. International Journal of Transgender Health. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, M., Ruocco, A., Ristori, J., Bonadonna, S., Pivonello, R., Meriggiola, M. C., Motta, G., Lombardo, F., Mosconi, M., Oppo, A., Federici, S., Bruno, L., Verde, N., Lami, A., Crespi, C. M., Manoli, M., Matarrese, P., Santangelo, C., Giordani, L., … Pierdominici, M. (2025). Stratified analysis of health and gender-affirming care among Italian transgender and gender diverse adults. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuno, E. (2019). Nonbinary-affirming psychological interventions. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H. M., Mocarski, R., Holt, N. R., Hope, D. A., King, R. E., & Woodruff, N. (2020). Unmet expectations in health care settings: Experiences of transgender and gender diverse adults in the Central Great Plains. Qualitative Health Research, 30(3), 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I. M., Schwartz, S., & Frost, D. M. (2008). Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer excess exposure and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzalira, S., Carone, N., Bochicchio, V., Cruciani, G., Quintigliano, M., & Scandurra, C. (2024). The healthcare experiences of LGBT+ individuals in Europe: A systematic review. In Sexuality research and social policy. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzalira, S., Carone, N., Bochicchio, V., Villani, S., Cruciani, G., Quintigliano, M., & Scandurra, C. (2025). Trans in treatment: A mixed-method systematic review on the psychotherapeutic experiences of transgender and gender diverse people. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 28(834). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J., Imel, Z., Tao, K. W., Wampold, B., Smith, A., & Rodolfa, E. (2011). Cultural ruptures in short-term therapy: Working alliance as a mediator between clients’ perceptions of microaggressions and therapy outcomes. Counselling & Psychotherapy Research, 11(3), 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, S., Carrier, E., Rich, E., & Kellermann, A. (2010). Where Americans get acute care: Increasingly, it’s not at their doctor’s office. Health Affairs, 29(9), 1620–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, K. E., Brennan-Ing, M., Chang, S. C., Dickey, L. M., Singh, A. A., Bower, K. L., & Witten, T. M. (2016). Providing competent and affirming services for transgender and gender nonconforming older adults. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health, 39(5), 366–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poteat, T., German, D., & Kerrigan, D. (2013). Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Social Science & Medicine, 84, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premji, K., Ryan, B. L., Hogg, W. E., & Wodchis, W. P. (2018). Patients’ perceptions of access to primary care: Analysis of the QUALICOPC patient experiences survey. Canadian Family Physician—Medecin de Famille Canadien, 64(3), 212–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prunas, A., Bandini, E., Fisher, A. D., Maggi, M., Pace, V., Quagliarella, L., Todarello, O., & Bini, M. (2018). Experiences of discrimination, harassment, and violence in a sample of Italian transsexuals who have undergone sex-reassignment surgery. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(14), 2225–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, K., Job, S., Blackwell, C., Sanchez, K., Carter, S., & Taliaferro, L. (2024). Provider cultural competence and humility in healthcare interactions with transgender and nonbinary young adults. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 56, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, J., Blaszcyk, W., Täuber, L., Dekker, A., Briken, P., & Nieder, T. O. (2021). Barriers to accessing health care in rural regions by transgender, non-binary, and gender diverse people: A case-based scoping review. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 12, 717821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritterbusch, A. E., Correa Salazar, C., & Correa, A. (2018). Stigma-related access barriers and violence against trans women in the Colombian healthcare system. Global Public Health, 13(12), 1831–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, M., Fredriksen-Goldsen, K., & Kim, H. J. (2024). Development of a multidimensional measure of health care access among LGBTQ midlife and older adults in the United States. SSM—Health Systems, 3, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, J., & Werbart, A. (2013). Therapist and relationship factors influencing dropout from individual psychotherapy: A literature review. Psychotherapy Research, 23(4), 394–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, M. A., Livingston, N. A., Berke, D. S., Matza, A. R., & Shipherd, J. C. (2019). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender veterans’ experiences of discrimination in health care and their relation to health outcomes: A pilot study examining the moderating role of provider communication. Health Equity, 3(1), 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaria, F., Scandurra, C., Mezzalira, S., Bochicchio, V., Salerno, M., Di Mase, R., & Capalbo, D. (2024). Unmet needs of pediatricians in transgender-specific care: Results of a short-term training. Hormone Research in Paediatrics, 97(3), 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandurra, C., Bochicchio, V., Amodeo, A. L., Esposito, C., Valerio, P., Maldonato, N. M., Bacchini, D., & Vitelli, R. (2018). Internalized transphobia, resilience, and mental health: Applying the Psychological Mediation Framework to Italian transgender individuals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(3), 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, C., Vitelli, R., Maldonato, N. M., Valerio, P., & Bochicchio, V. (2019). A qualitative study on minority stress subjectively experienced by transgender and gender nonconforming people in Italy. Sexologies, 28(3), e61–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological & Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelman, K. L., & Poteat, T. (2020). Strategies used by transmasculine and non-binary adults assigned female at birth to resist transgender stigma in healthcare. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(3), 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevington, S. M., Lotfy, M., O’Connell, K. A., & WHOQOL Group. (2004). The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 13(2), 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starfield, B., & Shi, L. (2004). The medical home, access to care, and insurance: A review of evidence. Pediatrics, 113(Suppl. S5), 1493–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R., Wu, L., Barnett, S., Deyo, P., & Swartwout, E. (2019). Socio-demographic predictors associated with capacity to engage in health care. Patient Experience Journal, 6, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundus, A., Younas, A., & Giwa, S. (2025). Meaning of person-inclusive care and care expectations of transgender individuals from healthcare professionals: An integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaac, A. R., Benotsch, E. G., & Barnes, A. J. (2019). Mediation models of perceived medical heterosexism, provider-patient relationship quality, and cervical cancer screening in a community sample of sexual minority women and gender nonbinary adults. LGBT Health, 6(2), 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatum, A. K., Catalpa, J., Bradford, N. J., Kovic, A., & Berg, D. R. (2020). Examining identity development and transition differences among binary transgender and genderqueer nonbinary (GQNB) individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(4), 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R. J., Habarth, J., Peta, J., Balsam, K., & Bockting, W. (2015). Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teti, M., Kerr, S., Bauerband, L. A., Koegler, E., & Graves, R. (2021). A qualitative scoping review of transgender and gender non-conforming people’s physical healthcare experiences and needs. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 598455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, R., Osborn, R., Mossialos, E., Djordjevic, A., & Wharton, G. (Eds.). (2020). 2020 international profiles of health care systems. Available online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/International_Profiles_of_Health_Care_Systems_Dec2020.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Velasco, R. A. F. (2022). Stigma among transgender and gender-diverse people accessing healthcare: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(3), 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, R. A. F., Slusser, K., & Coats, H. (2022). Stigma and healthcare access among transgender and gender-diverse people: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78, 3083–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, E., Jackson, L. A., & Marshall, E. G. (2018). Improving healthcare providers’ interactions with trans patients: Recommendations to promote cultural competence. Healthcare Policy=Politiques de Sante, 14(1), 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Vogelsang, A. C., Milton, C., Ericsson, I., & Strömberg, L. (2016). ‘Wouldn’t it be easier if you continued to be a guy?’. A qualitative interview study of transsexual persons’ experiences of encounters with healthcare professionals. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(23–24), 3577–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J., Shaver, J., & Stephenson, R. (2016). Outness, stigma, and primary health care utilization among rural LGBT populations. PLoS ONE, 11(1), e0146139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Hughto, J. M., Reisner, S. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeluf, G., Dhejne, C., Orre, C., Nilunger Mannheimer, L., Deogan, C., Höijer, J., & Ekéus Thorson, A. (2016). Health, disability and quality of life among trans people in Sweden: A web-based survey. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Dupre, M. E., Qiu, L., Zhou, W., Zhao, Y., & Gu, D. (2018). Age and sex differences in the association between access to medical care and health outcomes among older Chinese. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binary (n = 48) | Nonbinary (n = 84) | Total Sample (n = 132) | p | |

| Age (M ± SD) | 31 ± 11.1 | 27.1 ± 6.4 | 28.5 ± 8.6 | <0.001 |

| Sex assigned at birth | 0.200 | |||

| Male | 14 (29.2%) | 14 (16.7%) | 28 (21.2%) | |

| Female | 34 (70.8%) | 68 (81%) | 102 (77.3%) | |

| Intersex | – | 2 (2.4%) | 2 (1.5%) | |

| Total | 48 (100%) | 84 (100%) | 132 (100%) | |

| Educational level | 0.470 | |||

| ≤high school | 22 (45.8%) | 33 (39.3%) | 55 (41.7%) | |

| ≥college | 26 (54.2%) | 51 (60.7%) | 77 (58.3%) | |

| Total | 48 (100%) | 84 (100%) | 132 (100%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.727 | |||

| Caucasian | 47 (97.9%) | 81 (96.4%) | 128 (97%) | |

| Non-Caucasian | 1 (2.1%) a | 3 (3.6%) b | 4 (3%) | |

| Total | 48 (100%) | 84 (100%) | 132 (100%) | |

| Chronic disease(s) | 0.209 | |||

| Yes | 10 (20.8%) | 26 (31%) | 36 (27.3%) | |

| No | 38 (79.2%) | 58 (69%) | 96 (72.7%) | |

| Total | 48 (100%) | 84 (100%) | 132 (100%) | |

| Habitual source of primary care | 0.967 | |||

| Yes | 39 (81.3%) | 68 (81%) | 107 (81.1%) | |

| No | 9 (18.8%) | 16 (19%) | 25 (18.9%) | |

| Total | 48 (100%) | 84 (100%) | 132 (100%) | |

| Binary | Nonbinary | t | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M ± SD | |||||

| 1. Perceived stigma | – | 2.50 (0.70) | 2.48 (0.69) | 0.13 | −0.23, 0.26 | 0.69 | |||

| 2. Patient–provider relationship quality | −0.35 *** | – | 2.70 (0.67) | 2.45 (0.57) | 2.23 * | 0.03, 0.46 | 0.61 | ||

| 3. Barriers to care | 0.37 *** | −0.34 *** | – | 2.02 (0.64) | 1.96 (0.53) | 0.62 | −0.14, 0.27 | 0.57 | |

| 4. Quality of life | −0.44 *** | 0.27 ** | −0.42 *** | – | 0.79 (0.20) | 0.70 (0.24) | 2.09 * | 0.00, 0.17 | 0.23 |

| β | SE | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: Patient–provider relationship quality | ||||

| Perceived stigma | ||||

| Binary | −0.54 | 0.13 | −0.80, −0.28 | 0.000 |

| Nonbinary | −0.16 | 0.08 | −0.33, 0.00 | 0.055 |

| Outcome: Barriers to care | ||||

| Perceived stigma | ||||

| Binary | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.03, 0.57 | 0.034 |

| Nonbinary | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.07, 0.40 | 0.006 |

| Patient–provider relationship quality | ||||

| Binary | −0.29 | 0.14 | −0.56, −0.02 | 0.038 |

| Nonbinary | −0.18 | 0.11 | −0.40, 0.03 | 0.096 |

| Outcome: Quality of life | ||||

| Perceived stigma (direct effect) | ||||

| Binary | −0.11 | 0.04 | −0.19, −0.02 | 0.015 |

| Nonbinary | −0.12 | 0.04 | −0.20, −0.05 | 0.000 |

| Patient–provider relationship quality | ||||

| Binary | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.11, 0.06 | 0.504 |

| Nonbinary | −0.00 | 0.05 | −0.09, 0.09 | 0.947 |

| Barriers to care | ||||

| Binary | −0.14 | 0.05 | −0.23, −0.05 | 0.004 |

| Nonbinary | −0.13 | 0.05 | −0.22, −0.03 | 0.009 |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| 1. Perceived stigma → patient–provider relationship quality → quality of life | ||||

| Binary | 0.05 | 0.09 | −0.14, 0.24 | |

| Nonbinary | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05, 0.05 | |

| 2. Perceived stigma → barriers to care → quality of life | ||||

| Binary | −0.14 | 0.09 | −0.34, 0.00 | |

| Nonbinary | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.20, −0.01 | |

| 3. Perceived stigma → patient–provider relationship quality → barriers to care → quality of life | ||||

| Binary | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.17, −0.00 | |

| Nonbinary | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.00 | |

| Total effect | ||||

| Binary | −0.16 | 0.04 | −0.08, −0.54 | 0.000 |

| Nonbinary | −0.16 | 0.03 | −0.23, −0.09 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mezzalira, S.; Cruciani, G.; Quintigliano, M.; Bochicchio, V.; Carone, N.; Scandurra, C. Perceived Stigma and Quality of Life in Binary and Nonbinary/Queer Transgender Individuals in Italy: The Mediating Roles of Patient–Provider Relationship Quality and Barriers to Care. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060113

Mezzalira S, Cruciani G, Quintigliano M, Bochicchio V, Carone N, Scandurra C. Perceived Stigma and Quality of Life in Binary and Nonbinary/Queer Transgender Individuals in Italy: The Mediating Roles of Patient–Provider Relationship Quality and Barriers to Care. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(6):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060113

Chicago/Turabian StyleMezzalira, Selene, Gianluca Cruciani, Maria Quintigliano, Vincenzo Bochicchio, Nicola Carone, and Cristiano Scandurra. 2025. "Perceived Stigma and Quality of Life in Binary and Nonbinary/Queer Transgender Individuals in Italy: The Mediating Roles of Patient–Provider Relationship Quality and Barriers to Care" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 6: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060113

APA StyleMezzalira, S., Cruciani, G., Quintigliano, M., Bochicchio, V., Carone, N., & Scandurra, C. (2025). Perceived Stigma and Quality of Life in Binary and Nonbinary/Queer Transgender Individuals in Italy: The Mediating Roles of Patient–Provider Relationship Quality and Barriers to Care. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(6), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060113