Perceived Stress and Society-Wide Moral Judgment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Societal Relevance of Moral Judgment Research and Its Relationship with Perceived Stress

1.2. Neo-Kohlbergian Approach to Moral Judgment

Previous Research on Perceived Stress and the Neo-Kohlbergian Approach to Moral Judgment

1.3. Utilitarian-Deontological (U-D) Moral Judgments

1.3.1. Perceived Stress and Utilitarian-Deontological Moral Judgment

1.3.2. Measuring Utilitarian-Deontological Moral Judgments

1.4. Research Goals and Hypotheses

1.4.1. Perceived Stress and Utilitarian-Deontological Moral Judgments

1.4.2. Perceived Stress and the Neo-Kohlbergian Approach to Moral Judgment

1.4.3. Sex as a Controlling Variable

2. Method

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. CNI Model

2.3.2. The Behavioral Defining Issue Test

2.3.3. The Perceived Stress Scale-10

2.3.4. Attention Check

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Correlation Analysis

2.4.2. Main Effect While Controlling for Sex

2.4.3. Exploring Quadratic Relationship

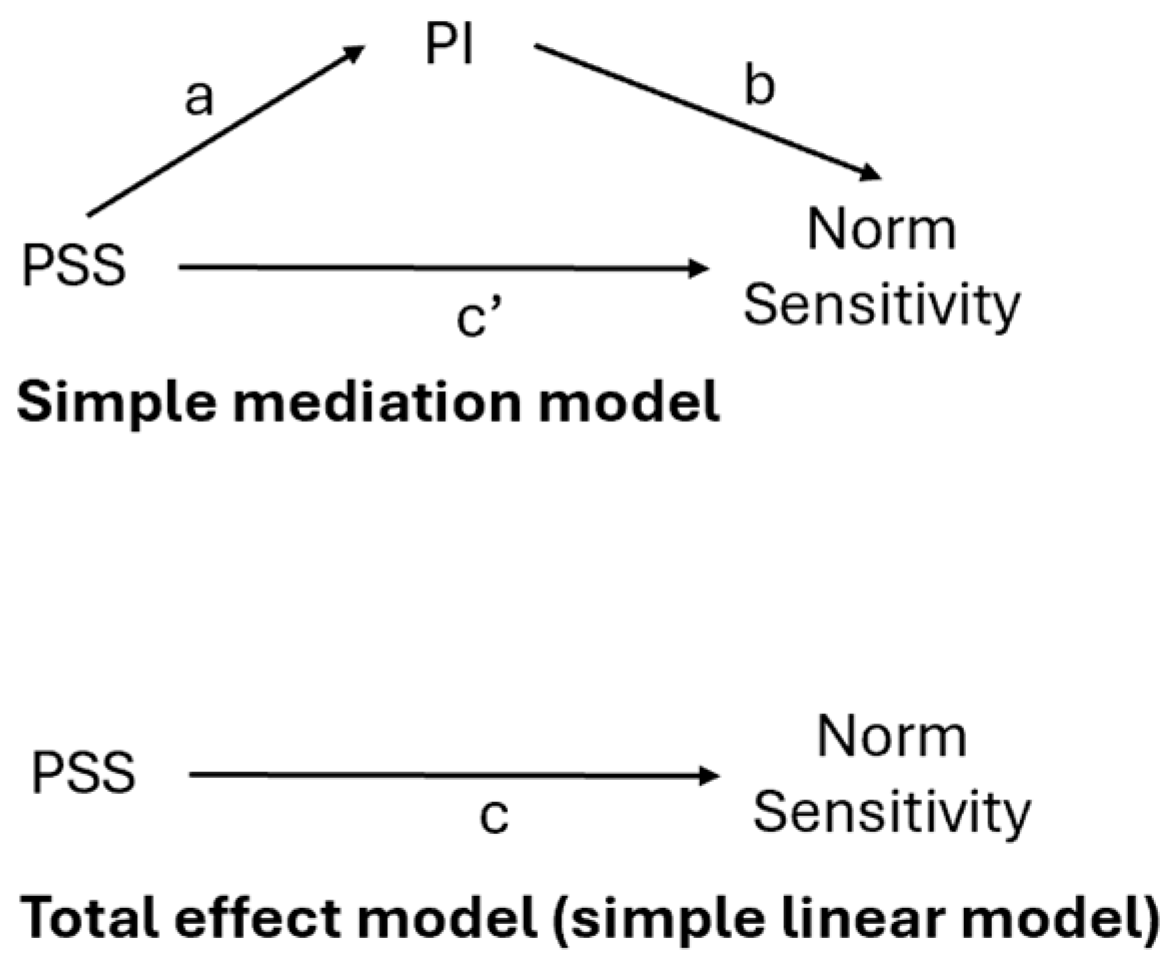

2.4.4. The Mediation Role of Moral Reasoning Development

3. Results

3.1. Perceived Stress and Neo-Kohlbergian Approach to Moral Judgment

3.2. Perceived Stress and the CNI Model Materials

3.3. The Mediation Effect of Moral Reasoning Schema on Perceived Stress and CNI Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings About Neo-Kohlbergian Approach to Moral Judgment

4.1.1. The Positive Correlation Between Perceived Stress and PI Schema

4.1.2. Perceived Stress and MN/PC Schema

4.1.3. Sex Differences

4.2. Findings About the CNI Model

4.2.1. Previous Studies on the Relationship Between Perceived Stress and Utilitarian-Deontological Moral Dilemma Judgment

4.2.2. Stress-Related Variables Lead to More Utilitarian Judgments

4.2.3. Other Observations

4.3. The Mediation Effect Between PSS and Norm Sensitivity Through PI Schema

4.4. Societal Changes and Generational Shifts—Another Potential Explanation of the Findings

4.5. Implications

4.5.1. Informing Moral Education Programs

4.5.2. Rising Stress Levels and Psychological Concerns

4.5.3. Societal Trends and the Need for Moral Education

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| U-D | Utilitarian-deontological |

| PI | Personal interest schema |

| MN | Maintaining norm schema |

| PC | Postconventional schema |

| C | Sensitivity to Consequence |

| N | Sensitivity to Norm |

| I | Inaction Preference |

| PSS | Perceived Stress Scale-10 |

| bDIT | behavioral Defining Issues Test |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| VIF | Variance inflation factors |

| LR | Likelihood Ratio |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| IV | Independent variable |

| DV | Dependent variable |

| M | Mediator |

| CI | Confidence intervals |

| 1 | To offer examples, some features that can influence the directive nature of a dilemmas include an extreme kill-save ratio—sacrificing one person to save a hundred—and the degree of self-involvement, such as whether the responder is directly involved in the sacrifice or among those being saved (Rosas et al., 2019). |

References

- Aknin, L. B., Barrington-Leigh, C. P., Dunn, E. W., Helliwell, J. F., Burns, J., Biswas-Diener, R., Kemeza, I., Nyende, P., Ashton-James, C. E., & Norton, M. I. (2013). Prosocial spending and well-being: Cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, Y., Feldman, B., Svarnik, O., Znamenskaya, I., Kolbeneva, M., Arutyunova, K., Krylov, A., & Bulava, A. (2020). Regression I. Experimental approaches to regression. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 65(2), 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Stress in America 2020: A nation recovering from collective trauma. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/report-october (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- American Psychological Association. (2023). Stress in America 2023: A nation recovering from collective trauma. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2023/collective-trauma-recovery (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Antoniou, R., Romero-Kornblum, H., Young, J. C., You, M., Kramer, J. H., & Chiong, W. (2021). Reduced utilitarian willingness to violate personal rights during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0259110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arutyunova, K. R., Alexandrov, Y. I., & Hauser, M. D. (2016). Sociocultural influences on moral judgments: East–west, male–female, and young–old. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayisi, D. N., & Krisztina, T. (2022). Gender roles and gender differences dilemma: An overview of social and biological theories. Journal of Gender, Culture and Society, 2(1), 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, V., & Lewis, T. (1994). Outliers in statistical data (vol. 3). Wiley New York. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, J., & Goodwin, G. P. (2020). Consequences, norms, and inaction: A critical analysis. Judgment and Decision Making, 15(3), 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, H. C., Bolyanatz, A., Crittenden, A. N., Fessler, D. M., Fitzpatrick, S., Gurven, M., Henrich, J., Kanovsky, M., Kushnick, G., & Pisor, A. (2016). Small-scale societies exhibit fundamental variation in the role of intentions in moral judgment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(17), 4688–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthol, R. P., & Ku, N. D. (1959). Regression under stress to first learned behavior. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59(1), 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavel, J. J. V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M. J., Crum, A. J., Douglas, K. M., & Druckman, J. N. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5), 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentham, J. (1970). An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation (J. H. Burns, & H. L. A. Hart, Eds.). Batoche Books. (Original work published 1789). [Google Scholar]

- Białek, M., & De Neys, W. (2017). Dual processes and moral conflict: Evidence for deontological reasoners’ intuitive utilitarian sensitivity. Judgment and Decision Making, 12(2), 148–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek, M., Paruzel-Czachura, M., & Gawronski, B. (2019). Foreign language effects on moral dilemma judgments: An analysis using the CNI model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 85, 103855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, A. M., Vestergren, S., & the COVIDiSTRESS II Consortium. (2022). COVIDiSTRESS diverse dataset on psychological and behavioural outcomes one year into the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Data, 9(1), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowerman, B. L., O’Connell, R. T., Murphree, E., Huchendorf, S. C., Porter, D. C., & Schur, P. (2003). Business statistics in practice. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Böckenholt, U. (2014). Modeling motivated misreports to sensitive survey questions. Psychometrika, 79, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, H. E., & Kent, T. B. (2022). Fifty years of declining confidence & increasing polarization in trust in American institutions. Daedalus, 151(4), 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, G., Eriksson, L., Goodin, R. E., & Southwood, N. (2013). Explaining norms. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (1998). Practical use of the information-theoretic approach. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cheema, S., Augustin, C., Göttlich, M., Krämer, U. M., & Beyer, F. (2024). Fragile mentalizing: Lack of behavioral and neural markers of social cognition in an established social perspective taking task when combined with stress induction. Eneuro, 11(11), ENEURO.0084-24.2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. (2025). Perceived stress and moral judgment among college students: Bridging the CNI model and bDIT framework [Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Alabama]. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Lugu, B., Ma, W., & Han, H. (2024). Scoring individual moral inclination for the CNI Test. Stats, 7(3), 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-J., Han, H., Dawson, K. J., Thoma, S. J., & Glenn, A. L. (2019). Measuring moral reasoning using moral dilemmas: Evaluating reliability, validity, and differential item functioning of the behavioural defining issues test (bDIT). European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 16(5), 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R. B., Baumann, D. J., & Kenrick, D. T. (1981). Insights from sadness: A three-step model of the development of altruism as hedonism. Developmental Review, 1(3), 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, R. F., & Zhu, Q. (2024). Exploring the relations between ethical reasoning and moral intuitions among Chinese engineering students in a course on global engineering ethics. European Journal of Engineering Education, 49(6), 1358–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, R. F., Zhu, Q., Streiner, S., Gammon, A., & Thorpe, R. (2025). Towards a psychologically realist, culturally responsive approach to engineering ethics in global contexts. Science and Engineering Ethics, 31(2), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the US In the social psychology of health: Claremont symposium on applied social psychology (S. Spacapam, & S. Oskamp, Eds.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, P., & Gawronski, B. (2013). Deontological and utilitarian inclinations in moral decision making: A process dissociation approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, C., Gulliford, L., Kristjánsson, K., & Paris, P. (2019). Phronesis and the knowledge-action gap in moral psychology and moral education: A new synthesis? Human Development, 62(3), 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denovan, A., Dagnall, N., Dhingra, K., & Grogan, S. (2019). Evaluating the perceived stress scale among UK university students: Implications for stress measurement and management. Studies in Higher Education, 44(1), 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickert, S., Sagara, N., & Slovic, P. (2011). Affective motivations to help others: A two-stage model of donation decisions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 24(4), 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissing, A. S., Jørgensen, T. B., Gerds, T. A., Rod, N. H., & Lund, R. (2019). High perceived stress and social interaction behaviour among young adults. A study based on objective measures of face-to-face and smartphone interactions. PLoS ONE, 14(7), e0218429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson College Polling. (2024, December). December 2024 national poll: Young voters diverge from majority on crypto, TikTok, and CEO assassination. Available online: https://emersoncollegepolling.com/december-2024-national-poll-young-voters-diverge-from-majority-on-crypto-tiktok-and-ceo-assassination/ (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Earp, B. D., McLoughlin, K. L., Monrad, J. T., Clark, M. S., & Crockett, M. J. (2021). How social relationships shape moral wrongness judgments. Nature Communications, 12(1), 5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesdorf, R., Conway, P., & Gawronski, B. (2015). Gender differences in responses to moral dilemmas: A process dissociation analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(5), 696–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawronski, B., Armstrong, J., Conway, P., Friesdorf, R., & Hütter, M. (2017). Consequences, norms, and generalized inaction in moral dilemmas: The CNI model of moral decision-making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(3), 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawronski, B., & Beer, J. S. (2017). What makes moral dilemma judgments “utilitarian” or “deontological”? Social Neuroscience, 12(6), 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawronski, B., Conway, P., Armstrong, J., Friesdorf, R., & Hütter, M. (2018). Effects of incidental emotions on moral dilemma judgments: An analysis using the CNI model. Emotion, 18(7), 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawronski, B., Conway, P., Hütter, M., Luke, D. M., Armstrong, J., & Friesdorf, R. (2020). On the validity of the CNI model of moral decision-making: Reply to Baron and Goodwin (2020). Judgment and Decision Making, 15(6), 1054–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, B. S., Hall, M. E., Dias-Karch, C., Haischer, M. H., & Apter, C. (2021). Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PLoS ONE, 16(8), e0255634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J. (2014). Moral tribes: Emotion, reason, and the gap between us and them. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J. D. (2009). Dual-process morality and the personal/impersonal distinction: A reply to McGuire, Langdon, Coltheart, and Mackenzie. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(3), 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron, 44(2), 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungordu, N., Nabizadehchianeh, G., O’Connor, E., Ma, W., & Walker, D. I. (2024). Moral reasoning development: Norms for defining issue test-2 (DIT2). Ethics & Behavior, 34(4), 246–263. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H. (2014). Analysing theoretical frameworks of moral education through Lakatos’s philosophy of science. Journal of Moral Education, 43(1), 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. (2023). Validating the behavioral Defining Issues Test across different genders, political, and religious affiliations. Experimental Results, 4, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. (2024a). Examining phronesis models with evidence from the neuroscience of morality focusing on brain networks. Topoi, 43(3), 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. (2024b). Examining the network structure among moral functioning components with network analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 217, 112435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. (2024c). Exploring the relationship between purpose and moral psychological indicators. Ethics & Behavior, 34(1), 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H., & Dawson, K. J. (2022). Improved model exploration for the relationship between moral foundations and moral judgment development using Bayesian Model Averaging. Journal of Moral Education, 51(2), 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Dawson, K. J., Thoma, S. J., & Glenn, A. L. (2020). Developmental level of moral judgment influences behavioral patterns during moral decision-making. The Journal of Experimental Education, 88(4), 660–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannikainen, I. R., Machery, E., & Cushman, F. A. (2018). Is utilitarian sacrifice becoming more morally permissible? Cognition, 170, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, S. H., Aziz, H. A., Zakariah, Z., Noor, S. M., Majid, M. R. A., & Karim, N. A. (2019). Development of linear regression model for brick waste generation in Malaysian construction industry. In Journal of physics: Conference series (vol. 1349, No. 1, p. 012112). IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, M., Cushman, F., Young, L., Kang-Xing Jin, R., & Mikhail, J. (2007). A dissociation between moral judgments and justifications. Mind & Language, 22(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlin, P., & Shutava, N. (2022). Trust in Government. Partnership for Public Service and Freedman Consulting. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y., Cheng, H., & Xie, J. (2025). Laying the foundations of phronesis (practical wisdom) through moral dilemma discussions in Chinese primary schools. Journal of Moral Education, 54(2), 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajonius, P. J., & Björkman, T. (2020). Dark malevolent traits and everyday perceived stress. Current Psychology, 39, 2351–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, I. (2016). Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals. In Seven masterpieces of philosophy (pp. 277–328). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Killing of Brian Thompson. (2025, June 2). In Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Killing_of_Brian_Thompson&oldid=1293639824 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Kooli, C. (2021). COVID-19: Public health issues and ethical dilemmas. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, 17, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, A., Deutsch, R., & Gawronski, B. (2020). Using the CNI model to investigate individual differences in moral dilemma judgments. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(9), 1392–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kossowska, M., Czernatowicz-Kukuczka, A., Szumowska, E., & Czarna, A. (2016). Cortisol and moral decisions among young men: The moderating role of motivation toward closure. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroneisen, M., & Heck, D. W. (2020). Interindividual differences in the sensitivity for consequences, moral norms, and preferences for inaction: Relating basic personality traits to the CNI model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(7), 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping (vol. 464). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.-H. (2012). Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nursing Research, 6(4), 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leys, C., Klein, O., Dominicy, Y., & Ley, C. (2018). Detecting multivariate outliers: Use a robust variant of the Mahalanobis distance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 74, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Gao, L., Zhao, X., & Li, B. (2021). Deconfounding the effects of acute stress on abstract moral dilemma judgment. Current Psychology, 40, 5005–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, M. (2019). “Younger people want to do it themselves”-self-actualization, commitment, and the reinvention of community. Qualitative Sociology, 42(2), 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, D. M., & Gawronski, B. (2021). Political ideology and moral dilemma judgments: An analysis using the CNI model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(10), 1520–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luke, D. M., & Gawronski, B. (2022). Temporal stability of moral dilemma judgments: A longitudinal analysis using the CNI model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(8), 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, D. M., Neumann, C. S., & Gawronski, B. (2022). Psychopathy and moral-dilemma judgment: An analysis using the four-factor model of psychopathy and the CNI model of moral decision-making. Clinical Psychological Science, 10(3), 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W., & Guo, W. (2019). Cognitive diagnosis models for multiple strategies. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 72(2), 370–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martíns, A. T., Sobral, T., Jiménez-Ros, A. M., & Faísca, L. (2022). The relationship between stress, negative (dark) personality traits, and utilitarian moral decisions. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 27(3), 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M., Attanasio, M., Pino, M. C., Masedu, F., Tiberti, S., Sarlo, M., & Valenti, M. (2020). Moral decision-making, stress, and social cognition in frontline workers vs. population groups during the COVID-19 pandemic: An explorative study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 588159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLoughlin, S., & Kristjánsson, K. (2025). Virtues as protective factors for adolescent mental health. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 35(1), e13004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, S., Thoma, S., & Kristjánsson, K. (2025). Was Aristotle right about moral decision-making? Building a new empirical model of practical wisdom. PLoS ONE, 20(1), e0317842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, S., Okan, Y., Hadjichristidis, C., & de Bruin, W. B. (2019). Age differences in moral judgment: Older adults are more deontological than younger adults. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 32(1), 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeeley, S., & Warner, J. J. (2015). Replication in criminology: A necessary practice. European Journal of Criminology, 12(5), 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A. B., Clark, B. A., & Kane, M. J. (2008). Who shalt not kill? Individual differences in working memory capacity, executive control, and moral judgment. Psychological Science, 19(6), 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahas, J. (2023). Intolerance of uncertainty and coping motives for drinking: Examining the mediating role of perceived stress [Doctoral dissertation, Concordia University]. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, B. K., Burns, B. D., Mak, K. K., Lah, S., Silva, D. S., Goldwater, M. B., & Kleitman, S. (2023). To kill or not to kill: A systematic literature review of high-stakes moral decision-making measures and their psychometric properties. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1063607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntontis, E., Blackburn, A. M., Han, H., Stöckli, S., Milfont, T. L., Tuominen, J., Griffin, S. M., Ikizer, G., Jeftic, A., Chrona, S., & Nasheedha, A. (2023). The effects of secondary stressors, social identity, and social support on perceived stress and resilience: Findings from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 88, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H. S., Christensen, K. S., Prior, A., & Christensen, K. B. (2024). The dimensionality of the perceived stress scale: The presence of opposing items is a source of measurement error. Journal of Affective Disorders, 344, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretorius, T. B. (2023). The perceived stress scale is essentially unidimensional: Complementary evidence from ancillary bifactor indices and Mokken analysis. Acta Psychologica, 241, 104058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahardjo, W., Juneman, J., & Setiani, Y. (2013). Computer anxiety, academic stress, and academic procrastination on college students. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 7(3), 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K., Schotter, E. R., Masson, M. E., Potter, M. C., & Treiman, R. (2016). So much to read, so little time: How do we read, and can speed reading help? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17(1), 4–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, J. R. (1982). A psychologist looks at the teaching of ethics. Hastings Center Report, 12(1), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, J. R., Thoma, S. J., & Bebeau, M. J. (1999). Postconventional moral thinking: A neo-Kohlbergian approach. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, L. E. (2020). Pyschosocial barriers to undergraduate students’ moral judgment. The University of Alabama. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas, A., Bermúdez, J. P., & Aguilar-Pardo, D. (2019). Decision conflict drives reaction times and utilitarian responses in sacrificial dilemmas. Judgment and Decision Making, 14(5), 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M., & Altmann, T. (2019). A multi-informant study of the influence of targets’ and perceivers’ social desirability on self-other agreement in ratings of the HEXACO personality dimensions. Journal of Research in Personality, 78, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandi, C. (2013). Stress and cognition. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 4(3), 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A. F., & Finan, C. (2018). Linear regression and the normality assumption. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 98, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H. M., & Havercamp, S. M. (2014). Mental health for people with intellectual disability: The impact of stress and social support. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 119(6), 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septiari, D., Helmayunita, N., Serly, V., & Sari, V. F. (2020). Ethics in university: Cognitive moral development and gender. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(12), 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S. L., Jazaieri, H., & Goldin, P. R. (2012). Mindfulness-based stress reduction effects on moral reasoning and decision making. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(6), 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, N., Sommer, M., Döhnel, K., Zänkert, S., Wüst, S., & Kudielka, B. M. (2017). Acute psychosocial stress and everyday moral decision-making in young healthy men: The impact of cortisol. Hormones and Behavior, 93, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. J., Rosenberg, D. L., & Timothy Haight, G. (2014). An assessment of the psychometric properties of the perceived stress scale-10 (PSS 10) with business and accounting students. Accounting Perspectives, 13(1), 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollberger, S., Bernauer, T., & Ehlert, U. (2016). Stress influences environmental donation behavior in men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 63, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranca, M., Minsk, E., & Baron, J. (1991). Omission and commission in judgment and choice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 27(1), 76–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcke, K., & Brand, M. (2012). Decision making under stress: A selective review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(4), 1228–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Starcke, K., Ludwig, A.-C., & Brand, M. (2012). Anticipatory stress interferes with utilitarian moral judgment. Judgment and Decision Making, 7(1), 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcke, K., Polzer, C., Wolf, O. T., & Brand, M. (2011). Does stress alter everyday moral decision-making? Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36(2), 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, J., Kirschbaum, C., Korb, F., Goschke, T., & Zwosta, K. (2025). Acute stress alters behavioral and neural mechanisms of self-controlled decision-making. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/osf/zbucw_v1 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Stults-Kolehmainen, M. A., & Sinha, R. (2014). The effects of stress on physical activity and exercise. Sports Medicine, 44, 81–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulkowski, J. P. (2020). Reducing moral distress in the setting of a public health crisis. Annals of Surgery, 272(6), e300–e302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawabieh, A. M., & Qaisy, L. M. (2012). Assessing stress among university students. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 2(2), 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Thoma, S., Bebeau, M., Dong, Y., Liu, W., & Jiang, H. (2011). Guide for DIT-2. Center for the Study of Ethical Development, the University of Alabama. [Google Scholar]

- Thoma, S. J. (1986). Estimating gender differences in the comprehension and preference of moral issues. Developmental Review, 6(2), 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, S. J. (2014). Measuring moral thinking from a neo-Kohlbergian perspective. Theory and Research in Education, 12(3), 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Carter, N. T. (2014). Declines in trust in others and confidence in institutions among American adults and late adolescents, 1972–2012. Psychological Science, 25(10), 1914–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, J., Marcora, S., De Pauw, K., Bailey, S., Meeusen, R., & Roelands, B. (2017). The effects of mental fatigue on physical performance: A systematic review. Sports Medicine, 47, 1569–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bos, K., Müller, P. A., & Damen, T. (2011). A behavioral disinhibition hypothesis of interventions in moral dilemmas. Emotion Review, 3(3), 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vveinhardt, J., Majauskiene, D., & Valanciene, D. (2020). Does perceived stress and workplace bullying alter employees’ moral decision-making? Gender-related differences. Transformations in Business & Economics, 19(1), 323–342. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, D. I., Thoma, S. J., Jones, C., & Kristjánsson, K. (2017). Adolescent moral judgement: A study of UK secondary school pupils. British Educational Research Journal, 43(3), 588–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M. K., & Meade, A. W. (2023). Dealing with careless responding in survey data: Prevention, identification, and recommended best practices. Annual Review of Psychology, 74(1), 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D. M., & Kruglanski, A. W. (1994). Individual differences in need for cognitive closure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L., Gan, Y., Ding, X., Wu, J., & Duan, H. (2021). The relationship between perceived stress and emotional distress during the COVID-19 outbreak: Effects of boredom proneness and coping style. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 77, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K., Tu, J., & Chen, T. (2019). Homoscedasticity: An overlooked critical assumption for linear regression. General Psychiatry, 32(5), e100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yentes, R. D. (2020). In search of best practices for the identification and removal of careless responders. North Carolina State University. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, F. F., Dookeeram, K., Basdeo, V., Francis, E., Doman, M., Mamed, D., Maloo, S., Degannes, J., Dobo, L., & Ditshotlo, P. (2012). Stress alters personal moral decision making. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(4), 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R. (2016). Stress potentiates decision biases: A stress induced deliberation-to-intuition (SIDI) model. Neurobiology of Stress, 3, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Wang, J., Geng, X., Li, C., & Wang, S. (2021). Objective assessments of mental fatigue during a continuous long-term stress condition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15, 733426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Kong, M., Li, Z., Zhao, X., & Gao, L. (2018). Chronic stress and moral decision-making: An exploration with the CNI model. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M., Li, H., & Gao, B. (2023). Mental fatigue increases utilitarian moral judgments during COVID-19. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 51(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Percentage of “Yes” Answers | Consequence Effect | Norm Effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prescriptive Norm | Proscriptive Norm | ||||||||

| Dilemma Name | Study No. | Benefits Greater Than Cost | Benefits Smaller Than Cost | Benefits Greater Than Cost | Benefits Smaller Than Cost | F | p | F | p |

| 7. Dialysis | 1a | 84.47% | 44.72% | 54.04% | 21.12% | 80.04 | <0.001 | 43.74 | <0.001 |

| 1b | 82.49% | 45.20% | 53.67% | 20.34% | 82.33 | <0.001 | 55.39 | <0.001 | |

| 8. Investor | 1a | 78.88% | 64.60% | 28.57% | 14.29% | 22.65 | <0.001 | 112.91 | <0.001 |

| 1b | 80.79% | 67.23% | 28.25% | 13.56% | 25.40 | <0.001 | 168.71 | <0.001 | |

| 9. Tyrant Killing | 1a | 77.64% | 52.80% | 45.34% | 23.60% | 41.09 | <0.001 | 38.33 | <0.001 |

| 1b | 74.01% | 62.15% | 46.33% | 26.55% | 23.94 | <0.001 | 50.07 | <0.001 | |

| 10. Rwanda | 1a | 88.20% | 82.61% | 26.09% | 16.15% | 9.84 | 0.002 | 235.45 | <0.001 |

| 1b | 86.44% | 83.62% | 30.51% | 20.34% | 7.97 | 0.005 | 233.65 | <0.001 | |

| 11. Mercy Killing | 1a | 88.20% | 61.49% | 40.99% | 9.94% | 65.47 | <0.001 | 196.32 | <0.001 |

| 1b | 83.05% | 60.45% | 40.11% | 16.38% | 48.45 | <0.001 | 132.48 | <0.001 | |

| 12. Nazi Occupation | 1a | 88.82% | 80.12% | 14.91% | 13.04% | 5.40 | 0.021 | 339.26 | <0.001 |

| 1b | 83.62% | 76.84% | 20.90% | 15.25% | 7.37 | 0.007 | 263.63 | <0.001 | |

| Variable | Mean | SD | n | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moral Reasoning Schema | 1. PI | 22.98% | 0.16 | 337 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. MN | 24.80% | 0.18 | 337 | −0.340 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. PC | 52.21% | 0.20 | 337 | −0.502 ** | −0.643 ** | 1 | |||||

| Moral Dilemma Judgment | 4. C | −0.80 | 0.59 | 337 | 0.09 | −0.206 ** | 0.116 * | 1 | |||

| 5. N | 0.40 | 0.67 | 337 | −0.229 ** | 0.201 ** | 0.002 | −0.367 ** | 1 | |||

| 6. I | 0.40 | 0.56 | 337 | 0.041 | −0.049 | 0.012 | 0.152 ** | −0.317 ** | 1 | ||

| Stress | 7. PSS | 20.91 | 6.96 | 337 | 0.107 * | −0.053 | 0.039 | 0.116 * | −0.188 ** | −0.041 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Lu, J.; Walker, D.I.; Ma, W.; Glenn, A.L.; Han, H. Perceived Stress and Society-Wide Moral Judgment. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060106

Chen Y, Lu J, Walker DI, Ma W, Glenn AL, Han H. Perceived Stress and Society-Wide Moral Judgment. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(6):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060106

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yi, Junfei Lu, David I. Walker, Wenchao Ma, Andrea L. Glenn, and Hyemin Han. 2025. "Perceived Stress and Society-Wide Moral Judgment" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 6: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060106

APA StyleChen, Y., Lu, J., Walker, D. I., Ma, W., Glenn, A. L., & Han, H. (2025). Perceived Stress and Society-Wide Moral Judgment. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(6), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060106