Cross-Sectional Analysis of Psychological Mediators Between Occupational Trauma and PTSD in Metropolitan Firefighters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Analytical Framework

2.2. Participants

2.3. Study Protocol

2.3.1. LEC-5 and PCL-5

2.3.2. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire 33 (CTQ-33)

2.3.3. Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES)

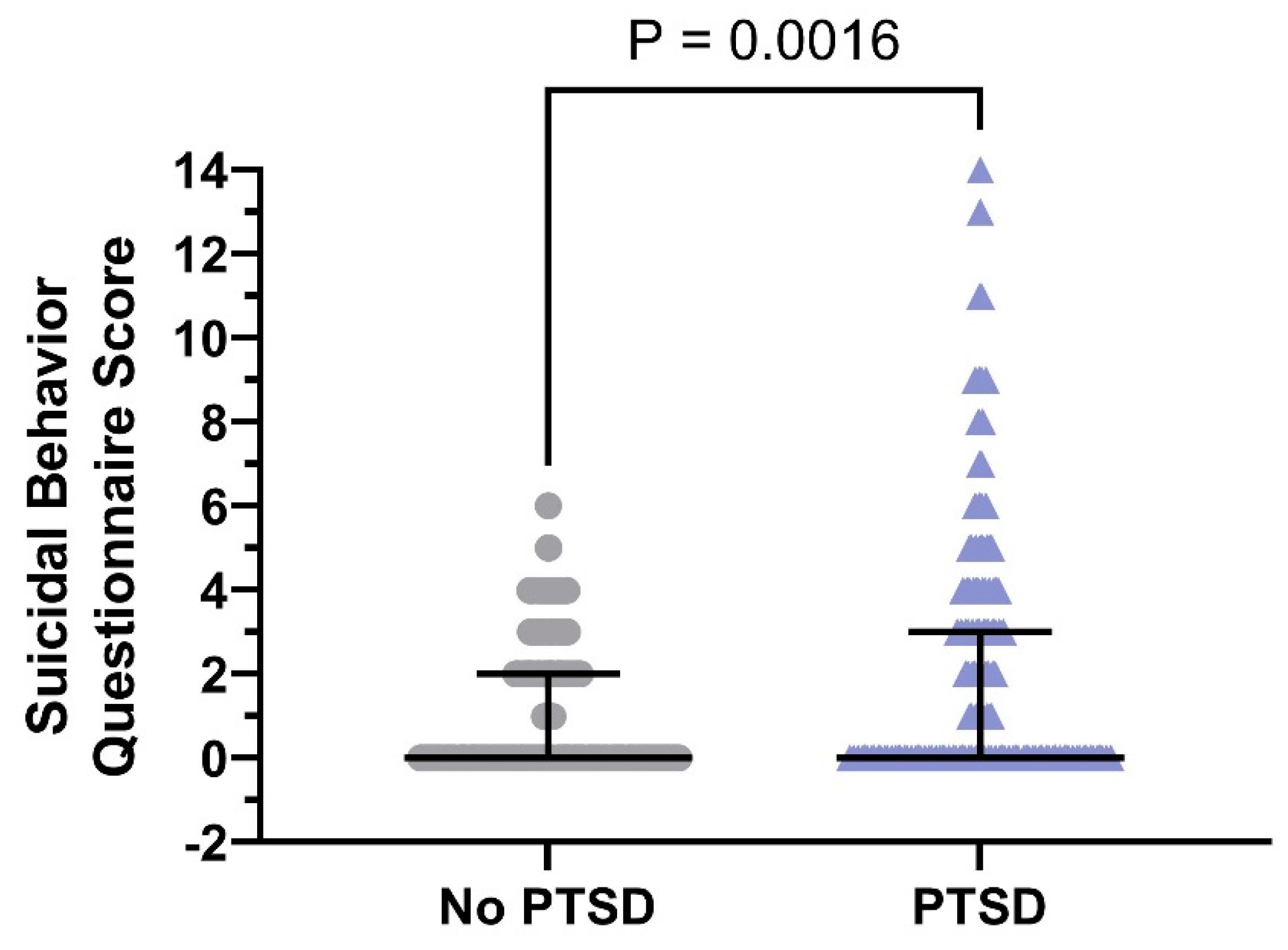

2.3.4. Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-4 (SBQ-4)

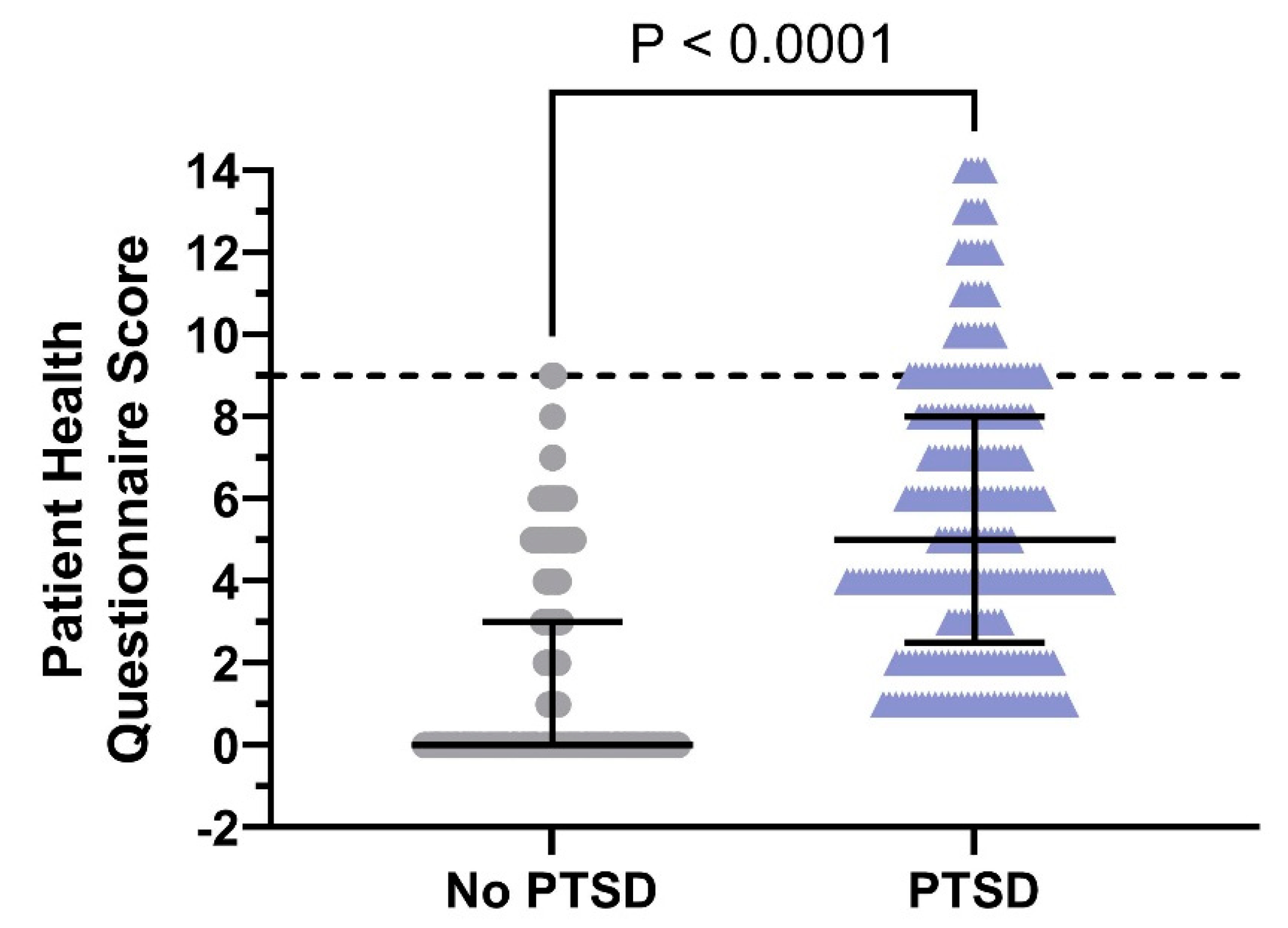

2.3.5. Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Psychometric Properties of the Instruments

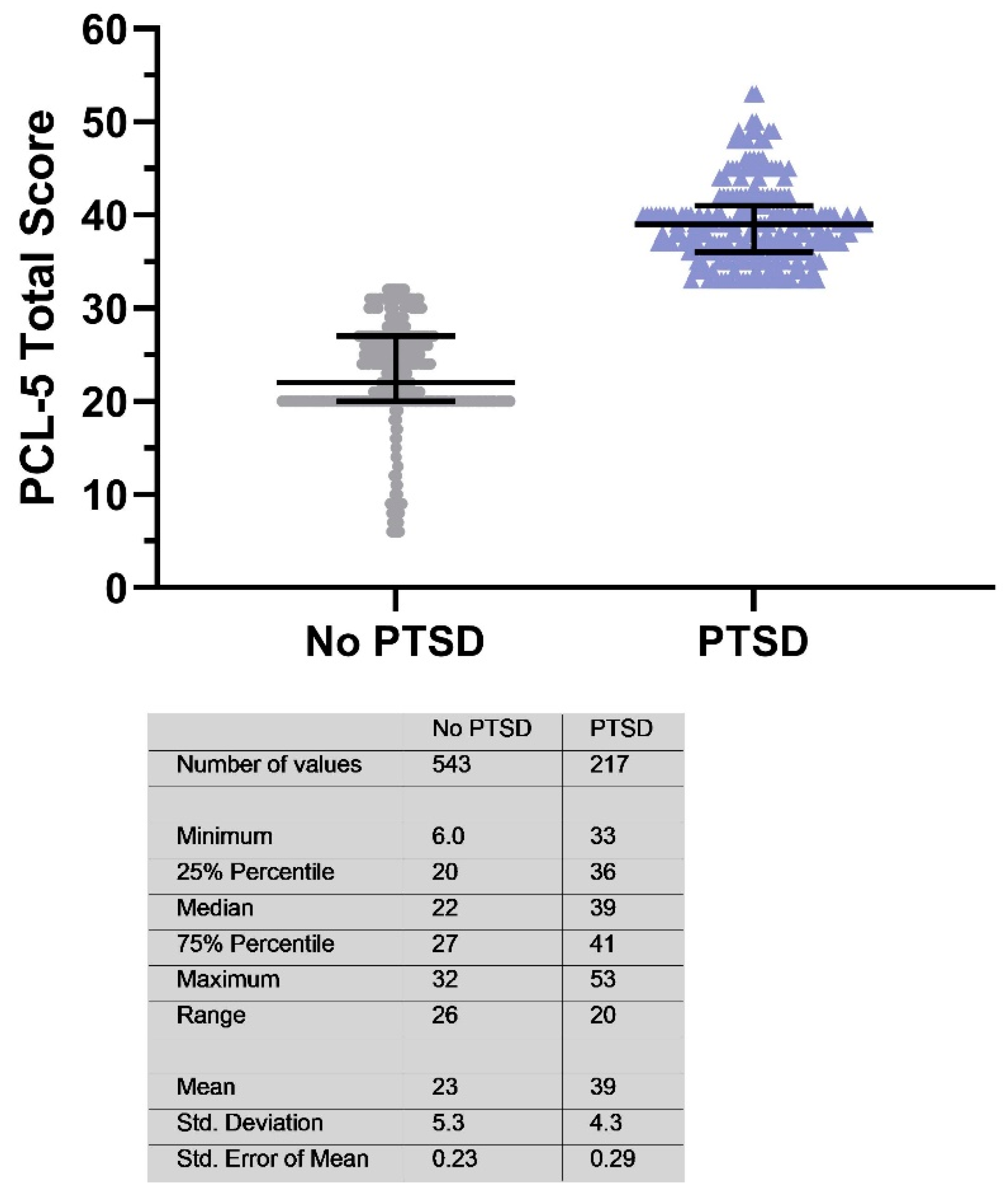

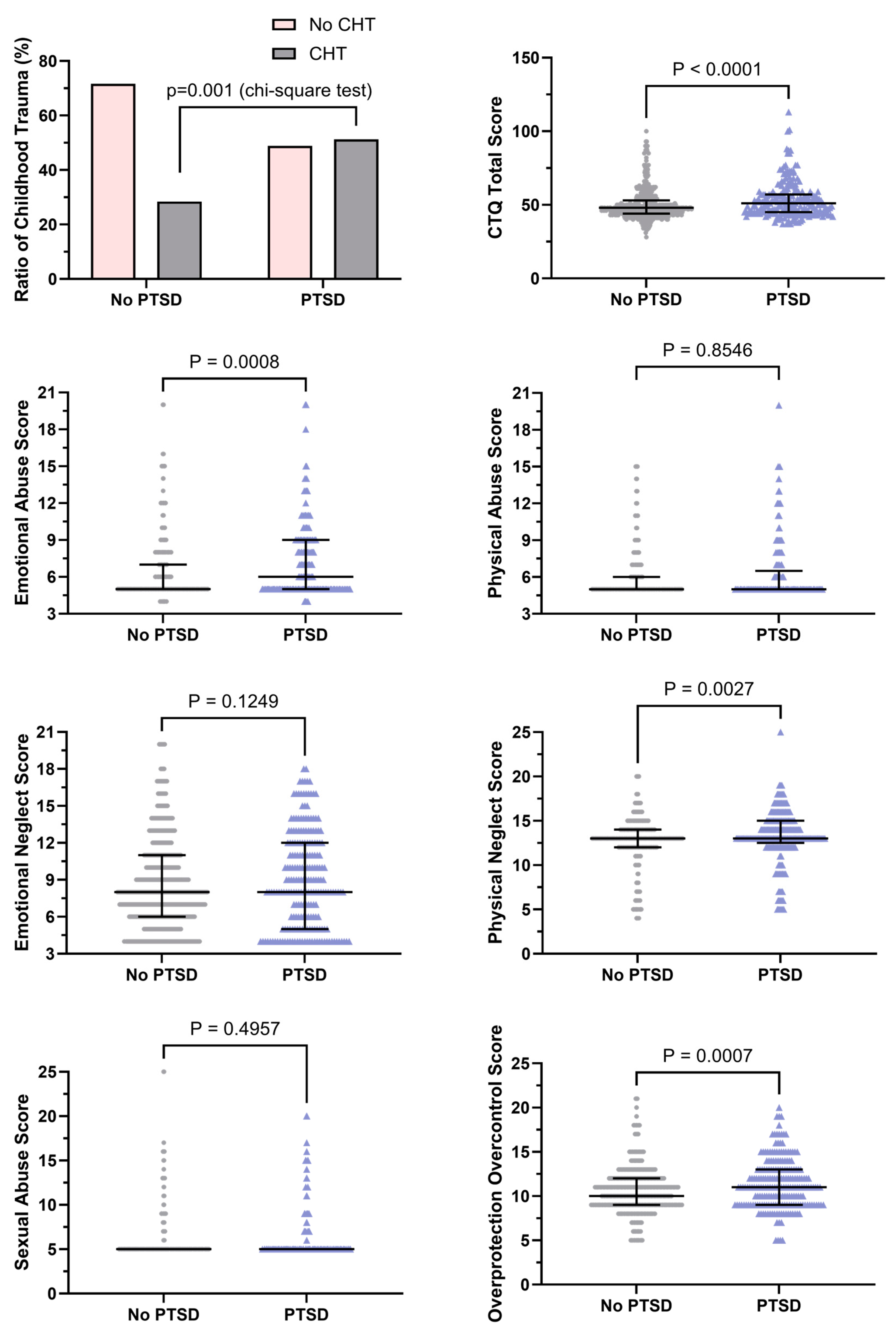

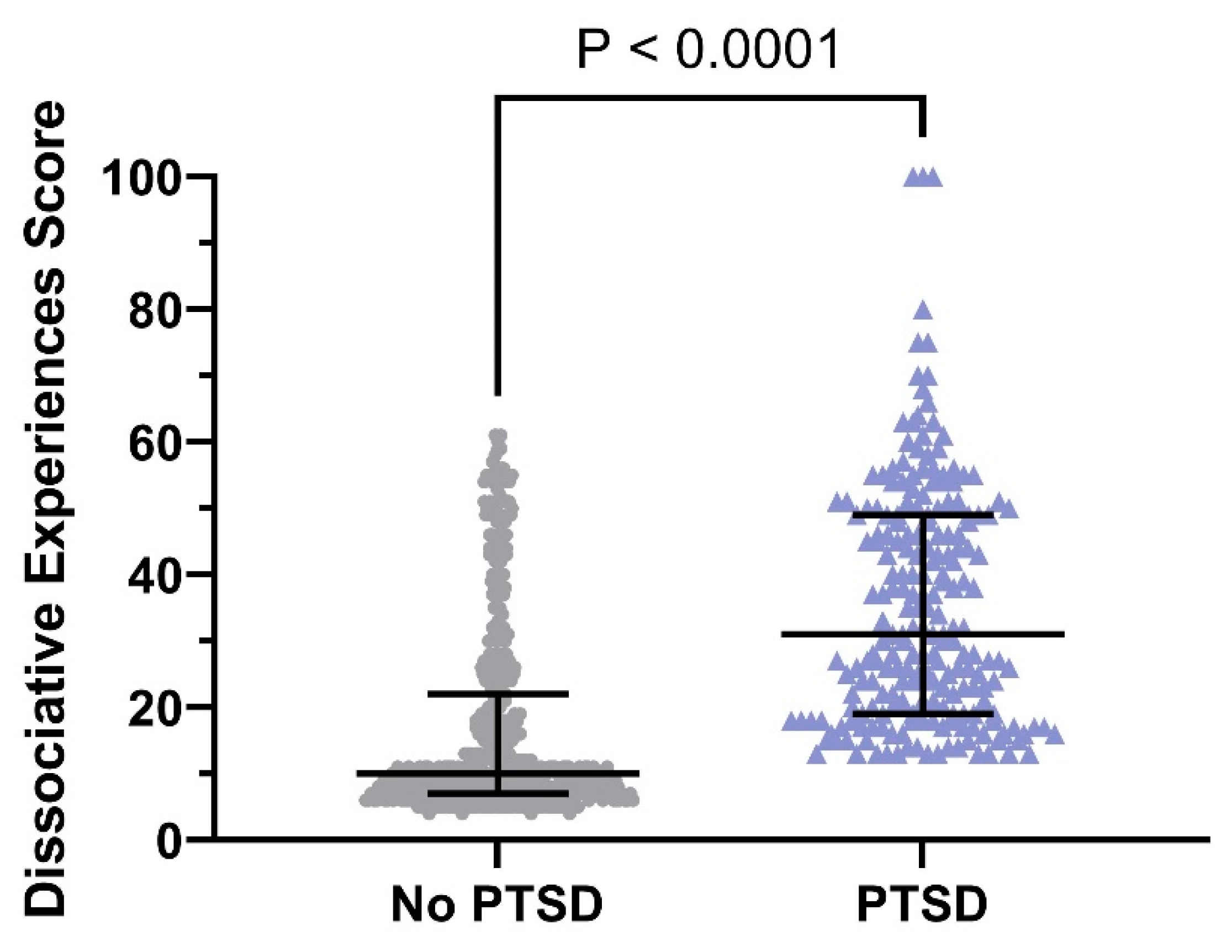

3.2. Results of Scale Data

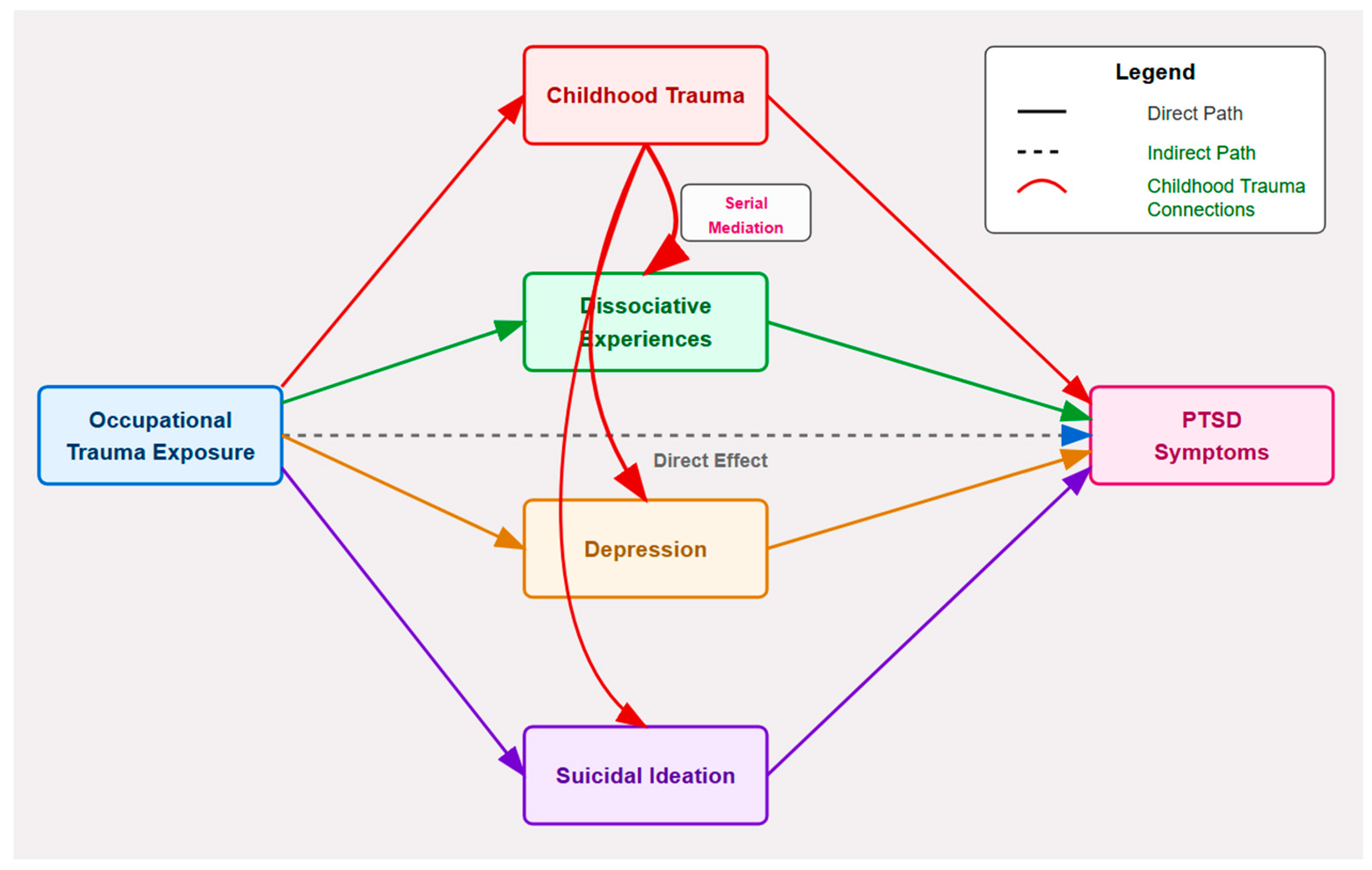

3.3. Mediational Pathway Analysis

4. Discussions

4.1. Main Results

4.2. Limitations, Strengths, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alshahrani, K. M., Johnson, J., Prudenzi, A., & O’Connor, D. B. (2022). The effectiveness of psychological interventions for reducing PTSD and psychological distress in first responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 17(8), e0272732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, L. D., & Smith, A. J. (2023). Adapting the primary care PTSD screener for firefighters. Occupational Medicine, 73(3), 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayam, G., Dilbaz, N., Bitlis, V., Holat, H., & Tüzer, T. (1995). İntihar davranışı ile depresyon, ümitsizlik, intihar düşüncesi ilişkisi: Intihar davranış ölçeği geçerlilik, güvenirlik çalışması [The relationship between suicidal behaviour and depression, hopelessness and suicidal ideation: The suicidaal behavior scale]. Kriz Dergisi, 3(1–2), 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E. M., & Putnam, F. W. (1986). Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 174(12), 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, M. P., Priest, S. J., Plume, R. C., & Wilson, E. E. (2022). Emergency first responders and professional wellbeing: A qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J. E., Protopopescu, A., O’Connor, C., Neufeld, R. W. J., Jetly, R., Hood, H. K., Lanius, R. A., & McKinnon, M. C. (2018). Dissociative symptoms mediate the relation between PTSD symptoms and functional impairment in a sample of military members, veterans, and first responders with PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1463794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boysan, M. (2014). Dissociative experiences are associated with obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a non-clinical sample: A latent profile analysis. Nöro Psikiyatri Arşivi, 51(3), 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boysan, M., Guzel Ozdemir, P., Ozdemir, O., Selvi, Y., Yilmaz, E., & Kaya, N. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (PCL-5). Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27(3), 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankardas, S., & Sofuoglu, Z. (2022). Determinants of traumatic stress symptoms in firefighters. Klinik Psikoloji Dergisi (KPD), 6(2), 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R. N., Afifi, T. O., Turner, S., Taillieu, T., Duranceau, S., LeBouthillier, D. M., Sareen, J., Ricciardelli, R., MacPhee, R. S., Groll, D., Hozempa, K., Brunet, A., Weekes, J. R., Griffiths, C. T., Abrams, K. J., Jones, N. A., Beshai, S., Cramm, H. A., Dobson, K. S., … Asmundson, G. J. G. (2018). Mental disorder symptoms among public safety personnel in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 63(1), 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, N., Galarneau, J., Haynes, W., & Sluggett, B. (2021). The role of organizational supports in mitigating mental ill health in firefighters: A cohort study in Alberta, Canada. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 64(7), 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramm, H., Richmond, R., Jamshidi, L., Edgelow, M., Groll, D., Ricciardelli, R., MacDermid, J. C., Keiley, M., & Carleton, R. N. (2021). Mental health of Canadian firefighters: The impact of sleep. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dautovich, N. D., Katjijova, M., Cyrus, J. W., & Kliewer, W. (2022). Duty-related stressors, adjustment, and the role of coping processes in first responders: A systematic review. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 15, S286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, H. (2018). The impact and long-term effects of childhood trauma. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 28(3), 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, S. B., Zimering, R. T., Knight, J., Morissette, S. B., Kamholz, B. W., Pennington, M. L., Dobani, F., Carpenter, T. P., Kimbrel, N. A., Keane, T. M., & Meyer, E. C. (2021). A prospective study of firefighters’ PTSD and depression symptoms: The first 3 years of service. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 13(1), 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, N. A., & Vujanovic, A. A. (2021). PTSD symptoms and suicide risk among firefighters: The moderating role of sleep disturbance. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 13(7), 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, C., Truchot, D., & Canevello, A. (2022). PTSD and PTG in French and American firefighters: A comparative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 11973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidi, H., & Yadollahie, M. (2012). Post-traumatic stress disorder. The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 3(1), 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. (2017). Describing the mental health profile of first responders: A systematic review. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 23(3), 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnick, A., Caulfield, N. M., Buerke, M., Stanley, I., Capron, D., & Vujanovic, A. (2024). Clinical and psychological implications of post-traumatic stress in firefighters: A moderated network study. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 53(2), 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. E., Dager, S. R., Jeong, H. S., Ma, J., Park, S., Kim, J., Choi, Y., Lee, S. L., Kang, I., Ha, E., Cho, H. B., Lee, S., Kim, E.-J., Yoon, S., & Lyoo, I. K. (2018). Firefighters, posttraumatic stress disorder, and barriers to treatment: Results from a nationwide total population survey. PLoS ONE, 13(1), e0190630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. I., Oh, S., Park, H., Min, B., & Kim, J.-H. (2020). The prevalence and clinical impairment of subthreshold PTSD using DSM-5 criteria in a national sample of Korean firefighters. Depress Anxiety, 37(4), 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. I., Park, H., & Kim, J.-H. (2018). The mediation effect of PTSD, perceived job stress and resilience on the relationship between trauma exposure and the development of depression and alcohol use problems in Korean firefighters: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 229, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langtry, J., Owczarek, M., McAteer, D., Taggart, L., Gleeson, C., Walshe, C., & Shevlin, M. (2021). Predictors of PTSD and CPTSD in UK firefighters. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1849524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. H., Park, S., & Sim, M. (2018). Relationship between ways of coping and posttraumatic stress symptoms in firefighters compared to the general population in South Korea. Psychiatry Research, 270, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S. (2019). Perceived social support functions as a resilience in buffering the impact of trauma exposure on PTSD symptoms via intrusive rumination and entrapment in firefighters. PLoS ONE, 14(8), e0220454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, L., Smith-MacDonald, L., Malloy, D. C., Anderson, G. S., Beshai, S., Ricciardelli, R., Bremault-Phillips, S., & Carleton, R. N. (2022). A qualitative analysis of the mental health training and educational needs of firefighters, paramedics, and public safety communicators in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Li, N., Zhang, L., Liu, Y., Zhang, T., Li, D., Bai, D., Liu, X., & Li, L. (2022). Predicting PTSD symptoms in firefighters using a fear-potentiated startle paradigm and machine learning. Journal of Affective Disorders, 319, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, M. M., & Nielsen, S. L. (1981). Assessment of suicide ideation and parasuicide: Hopelessness and social desirability. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49(5), 773–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushchak, O., Strilbytska, O., Koliada, A., & Storey, K. B. (2023). An orchestrating role of mitochondria in the origin and development of post-traumatic stress disorder. Frontiers in Physiology, 13, 1094076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majani, A. F., Ghazali, S. R., Yong, C. Y., Pauzi, N., Adenan, F., & Manogaran, K. (2022). Job-related psychological trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and depressive symptoms among Malaysian firefighters. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 76, 103248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K. A., & Lambert, H. K. (2017). Child trauma exposure and psychopathology: Mechanisms of risk and resilience. Current Opinion in Psychology, 14, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mureșanu, I. A., Grad, D. A., Mureșanu, D. F., Dobran, S.-A., Hapca, E., Strilciuc, Ștefan, Benedek, I., Capriș, D., Popescu, B. O., Perju-Dumbravă, L., & Cherecheș, R. M. (2022). Evaluation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and related comorbidities in clinical studies. Journal of Medicine and Life, 15(4), 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N., Pao, C., Dragomir-Davis, M., Tran, J., & Arbona, C. (2019). PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation in US female firefighters. Occupational Medicine (London), 69(8–9), 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, J., Aires Dias, J., Duarte, I. C., Caldeira, S., Marques, A. R., Rodrigues, V., Redondo, J., & Castelo-Branco, M. (2023). Mental health and post-traumatic stress disorder in firefighters: An integrated analysis from an action research study. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1259388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagou, C., & MacBeth, A. (2022). Deconstructing pathways to resilience: A systematic review of associations between psychosocial mechanisms and transdiagnostic adult mental health outcomes in the context of adverse childhood experiences. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(5), 1626–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranney, R. M., Bing-Canar, H., Paltell, K. C., Tran, J. K., Berenz, E. C., & Vujanovic, A. A. (2020). Cardiovascular risk as a moderator of associations among anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, PTSD and depression symptoms among trauma-exposed firefighters. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 139, 110269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, S. L., Andrews, K., Protopopescu, A., Lloyd, C., O’Connor, C., Losier, B. J., Lanius, R. A., & McKinnon, M. C. (2022). Mental health symptoms in public safety personnel: Examining the effects of adverse childhood experiences and moral injury. Child Abuse & Neglect, 123, 105394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglam, O., Ozturk, E., & Derin, G. (2025). Childhood traumas and dissociation in firefighters: The mediating role of suicidal desire. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Y. E., Kökoğlu, B., Balcıoğlu, H., Bilge, U., Colak, E., & Unluoglu, I. (2016). Validity and reliability study of Turkish patient. Biomedical research (India), health science and bio convergence technology: Edition-I: S460-S462. Available online: https://www.biomedres.info/abstract/turkish-reliability-of-the-patient-health-questionnaire9-6174.html (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Serrano-Ibáñez, E. R., Corrás, T., Del Prado, M., Diz, J., & Varela, C. (2023). Psychological variables associated with post-traumatic stress disorder in firefighters: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(4), 2049–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Chu, C., Dougherty, S. P., Gallyer, A. J., Spencer-Thomas, S., Shelef, L., Fruchter, E., Comtois, K. A., Gutierrez, P. M., Sachs-Ericsson, N. J., & Joiner, T. E. (2019). Perceptions of belongingness and social support attenuate PTSD symptom severity among firefighters: A multistudy investigation. Psychological Services, 16(4), 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şar, V., Necef, I., Mutluer, T., Fatih, P., & Türk-Kurtça, T. (2021). A revised and expanded version of the Turkish childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ–33): Overprotection-overcontrol as additional factor. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 22(1), 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, K. R. H., Lima, E., Vasconcelos, A., Nascimento, E., & Cox, T. (2019). Trauma and work factors as predictors of firefighters’ psychiatric distress. Occupational Medicine (Oxford, England), 69(8–9), 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013). The life events checklist for dsm-5 (lec-5). Instrument National Center for PTSD. Available online: www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Wolffe, T. A. M., Robinson, A., Clinton, A., Turrell, L., & Stec, A. A. (2023). Mental health of UK firefighters. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yargic, İ., Tutkun, H., & Şar, V. (1993). Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Dissociative Experiences Scale. Dissociation, 8(1), 10–13. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-39383-001 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakirci, A.E.; Sar, V.; Cetin, A. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Psychological Mediators Between Occupational Trauma and PTSD in Metropolitan Firefighters. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050075

Bakirci AE, Sar V, Cetin A. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Psychological Mediators Between Occupational Trauma and PTSD in Metropolitan Firefighters. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(5):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050075

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakirci, Ahmet Erhan, Vedat Sar, and Ali Cetin. 2025. "Cross-Sectional Analysis of Psychological Mediators Between Occupational Trauma and PTSD in Metropolitan Firefighters" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 5: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050075

APA StyleBakirci, A. E., Sar, V., & Cetin, A. (2025). Cross-Sectional Analysis of Psychological Mediators Between Occupational Trauma and PTSD in Metropolitan Firefighters. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(5), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050075