Ethical Climate, Intrinsic Motivation, and Affective Commitment: The Impact of Depersonalization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Contextualization

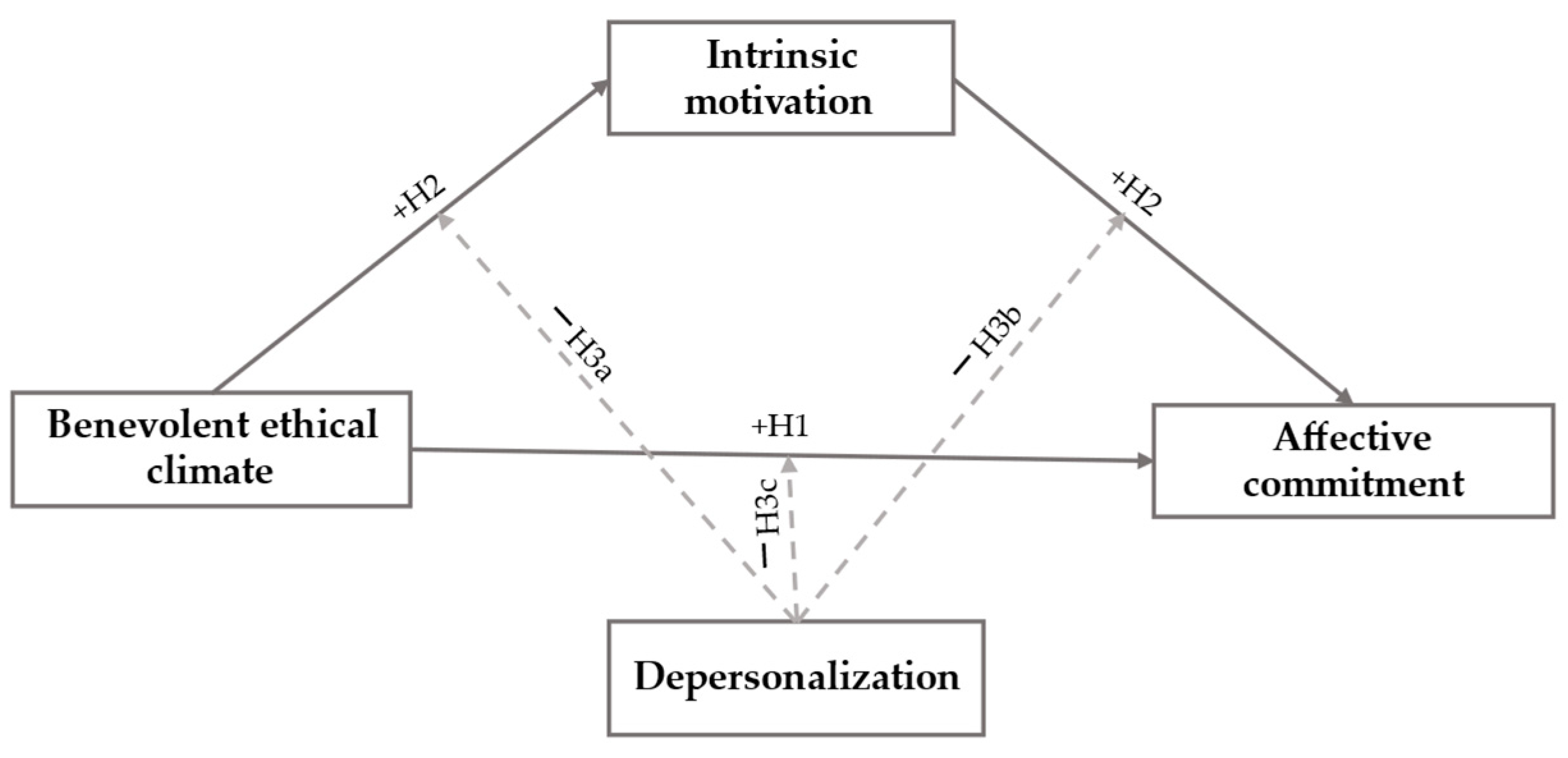

2.1. Benevolent Ethical Climate and Affective Commitment

2.2. Mediating Effect of Intrinsic Motivation

2.3. Moderating Effect of Depersonalization

3. Presentation of the Study

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Measures

Benevolent Ethical Climate

Intrinsic Motivation

Affective Commitment

Depersonalization

3.1.3. Procedure

3.1.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Discriminant Validity

4.3. Mediating Effect Analysis

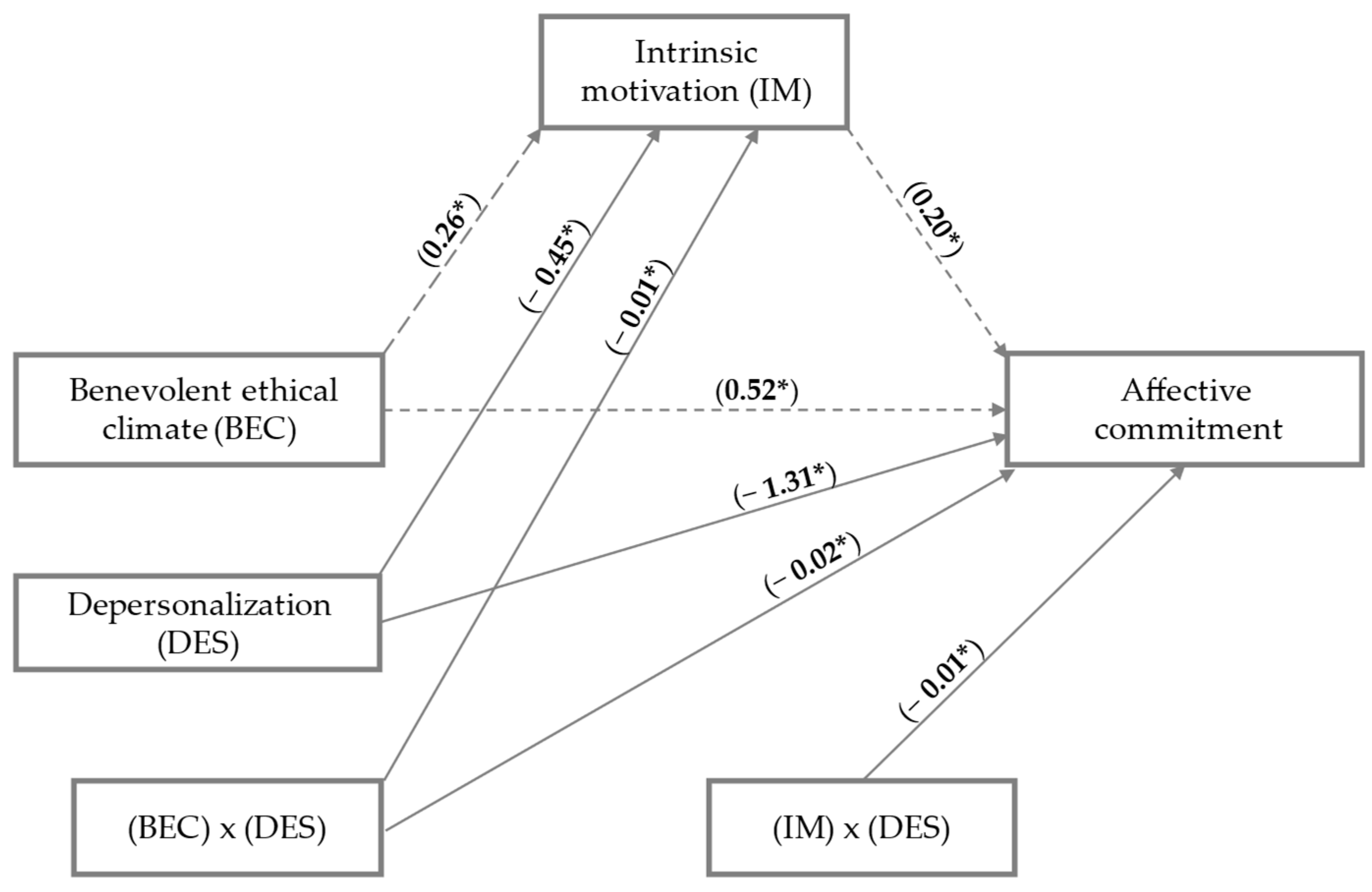

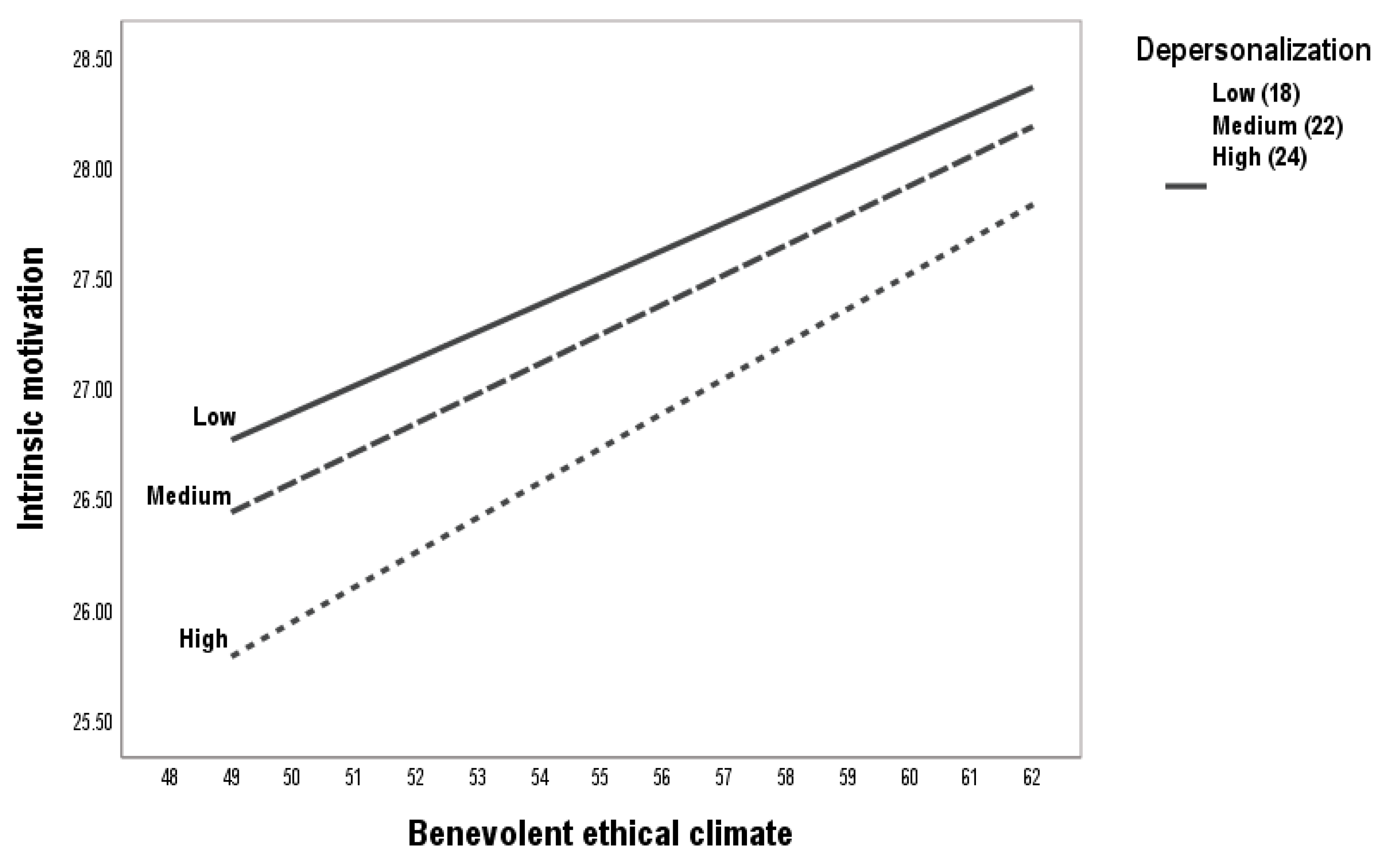

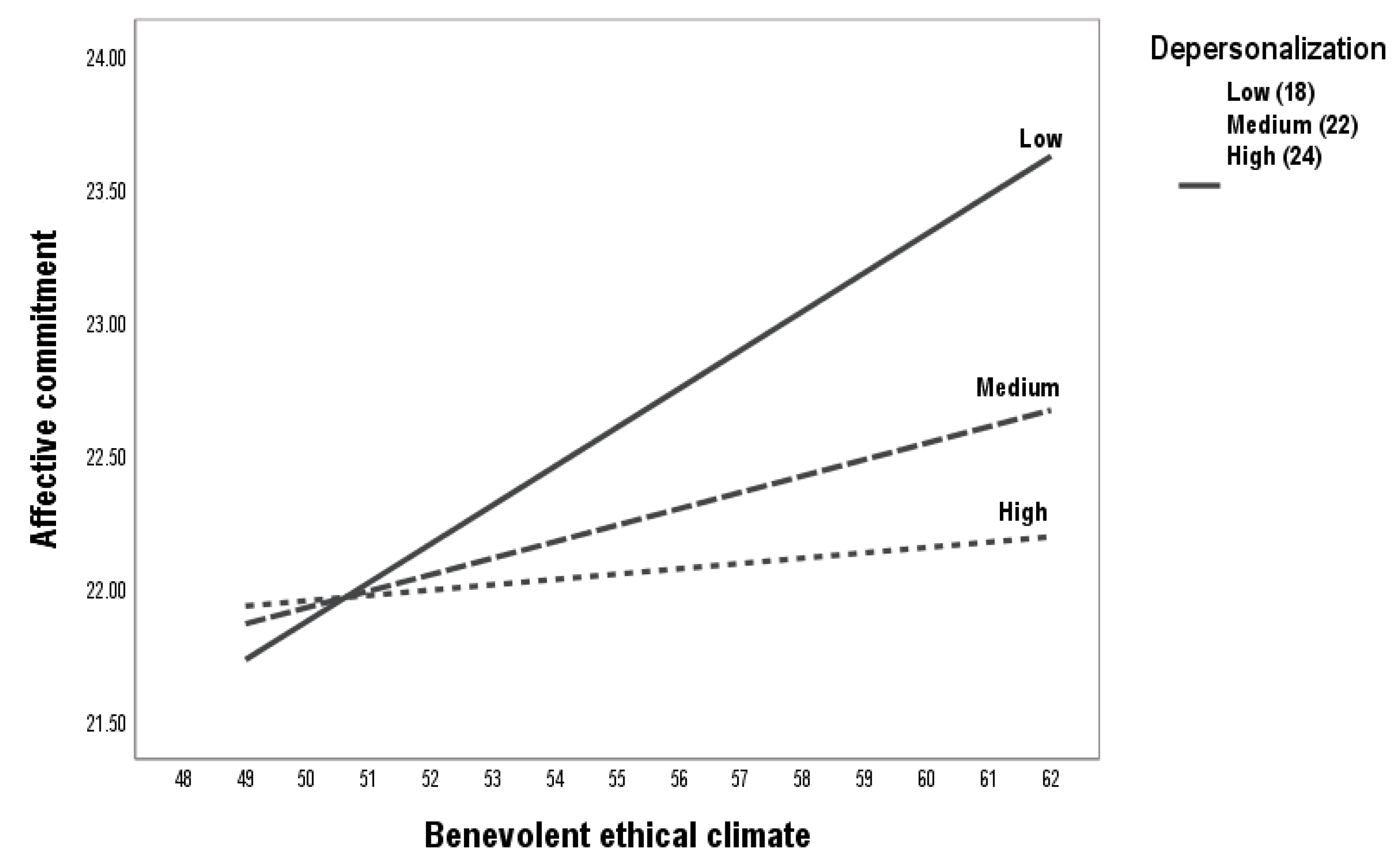

4.4. Moderated Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, R., Ahmad, S., Islam, T., & Kaleem, A. (2020). The nexus of corporate social responsibility (CSR), affective commitment and organisational citizenship behaviour in academia: A model of trust. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(1), 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F. O., Mondejar, R., & Chu, C. W. (2015). Accounting for the influence of overall justice on job performance: Integrating self-determination and social exchange theories. Journal of Management Studies, 52(2), 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante Boadi, E., He, Z., Bosompem, J., Opata, C. N., & Boadi, E. K. (2020). Employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its effects on internal outcomes. The Service Industries Journal, 40(9–10), 611–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis, E., Prasetio, A. P., Gustyana, T. T., Putril, S. F., & Rakhmawati, D. (2019). The mediation of intrinsic motivation and affective commitment in the relationship of transformational leadership and employee engagement in technology-based companies. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 20(1), 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Nassen, K. D. (1998). Representation of measurement error in marketing variables: Review of approaches and extension to three-facet designs. Journal of Econometrics, 89(1–2), 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldé, M., Ferreira, A. I., & Maynard, T. (2018). SECI driven creativity: The role of team trust and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(8), 1688–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benita, M., Butler, R., & Shibaz, L. (2019). Outcomes and antecedents of teacher depersonalization: The role of intrinsic orientation for teaching. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 1103–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological Inquiry, 34(2), 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, C., & Paulraj, A. (2013). Ethical climate and purchasing social responsibility: A benevolence focus. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(3), 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhani, F., Jalali, T., Abbaszadeh, A., & Haghdoost, A. (2014). Nurses’ perception of ethical climate and organizational commitment. Nursing Ethics, 21(3), 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouraoui, K., Bensemmane, S., Ohana, M., & Russo, M. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and employees’ affective commitment: A multiple mediation model. Management Decision, 57(1), 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueller, D., Brueller, N. N., & Doveh, E. (2020). Expressing negative emotions in work relationships and affective organizational commitment: A latent difference score approach. In C. E. J. Härtel, W. J. Zerbe, & N. M. Ashkanasy (Eds.), Research on emotion in organizations (pp. 173–192). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaunica, A., McEllin, L., Kiverstein, J., Gallese, V., Hohwy, J., & Woźniak, M. (2022). Zoomed out: Digital media use and depersonalization experiences during the COVID-19 lockdown. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaunica, A., Pienkos, E., Nakul, E., Madeira, L., & Farmer, H. (2023). Exploration of self- and world-experiences in depersonalization traits. Philosophical Psychology, 36(2), 380–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah, K. P., & Victor, B. (2003). The effects of ethical climates on organizational commitment: A two-study analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 46(2), 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O., & Akdogan, A. A. (2015). The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(1), 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derin, O. B., Toker, K., & Gorener, A. (2022). The relationship between knowledge sharing and innovative work behaviour: The mediating role of ethical climate. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 20(4), 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S. P. (1996). The impact of ethical climate types on facets of job satisfaction: An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(6), 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, M. S., & Plakalovic, V. (2016). Impact of caring climate, job satisfaction, and affective commitment on employees’ performance in the banking sector of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 9(18), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditlev-Simonsen, C. D. (2015). The relationship between norwegian and swedish employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility and affective commitment. Business & Society, 54(2), 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, M., Rezaei, S., Valaei, N., & Gardener, J. (2023). Creativity mindset as the organizational capability: The role of creativity-relevant processes, domain-relevant skills and intrinsic task motivation. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 15(1), 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erum, H., Abid, G., Contreras, F., & Islam, T. (2020). Role of family motivation, workplace civility and self-efficacy in developing affective commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(1), 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbach, A., & Woolley, K. (2022). The structure of intrinsic motivation. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9(1), 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural Equation Models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W., & Deshpande, S. P. (2012). Antecedents of organizational commitment in a Chinese construction company. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(3), 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W., & Deshpande, S. P. (2014). The impact of caring climate, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment on job performance of employees in a China’s insurance company. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(2), 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M., Forest, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Crevier-Braud, L., Van Den Broeck, A., Aspeli, A. K., Bellerose, J., Benabou, C., Chemolli, E., Güntert, S. T., Halvari, H., Indiyastuti, D. L., Johnson, P. A., Molstad, M. H., Naudin, M., Ndao, A., Olafsen, A. H., Roussel, P., Wang, Z., & Westbye, C. (2015). The multidimensional work motivation scale: Validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(2), 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, M., Portoghese, I., & Battistelli, A. (2011). Intrinsic Motivation, job autonomy and turnover intention in the italian healthcare: The mediating role of affective commitment. Journal of Management Research, 3(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J., & Mazereeuw-Van Der Duijn Schouten, C. (2012). Motives for corporate social responsibility. De Economist, 160(4), 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grdinovac, J. A., & Yancey, G. B. (2012). How organizational adaptations to recession relate to organizational commitment. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 15(1), 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guohao, L., Pervaiz, S., & Qi, H. (2021). Workplace friendship is a blessing in the exploration of supervisor behavioral integrity, affective commitment, and employee proactive behavior—An empirical research from service industries of pakistan. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidaton, U., Lee, M. S., Ismail, A., Shahida, N., & Sanusi, A. (2018). Ethical climate as a determinant of organizational commitment. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 8(8), 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefny, L. (2021). The relationships between job satisfaction dimensions, organizational commitment and turnover intention: The moderating role of ethical climate in travel agencies. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 20(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., & Lilly, R. S. (1993). Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology, 21(2), 128–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Y.-P., Peng, C.-Y., Chou, M.-T., Yeh, C.-T., & Zhang, Q. (2020). Workplace friendship, helping behavior, and turnover intention: The meditating effect ofaffective commitment. Advances in Management and Applied Economics, 10(5), 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C., You, C.-S., & Tsai, M.-T. (2012). A multidimensional analysis of ethical climate, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Nursing Ethics, 19(4), 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M., Moon, T.-W., & Ko, S.-H. (2018). How employees’ perceptions of csr increase employee creativity: Mediating mechanisms of compassion at work and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Business Ethics, 153(3), 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibragimov, Y., & Berishvili, N. B. (2023). Analysis of intrinsic motivation influence on employee affective commitment during digital change. London Journal of Social Sciences, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L., Chen, R., Jing, L., Qiao, Y., Lou, J., Xu, J., Wang, J., Chen, W., & Sun, X. (2017). Development and enrolee satisfaction with basic medical insurance in China: A systematic review and stratified cluster sampling survey. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 32(3), 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazei, M., Shukor, A. R., & Biotech, M. (2020). A novel instrument for integrated measurement and assessment of intrinsic motivation, team climate, and burnout in multidisciplinary teams. The Permanente Journal, 24(2), 19.155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieserling, A. (2019). Blau (1964): Exchange and power in social life. In B. Holzer, & C. Stegbauer (Eds.), Schlüsselwerke der netzwerkforschung (pp. 51–54). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (1998). Software review: Software programs for structural equation modeling: Amos, EQS, and LISREL. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 16(4), 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). The mediation myth. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37(4), 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, J. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and employees motivation—Broadening the perspective. Schmalenbach Business Review, 72(2), 159–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N., Zhang, L., Li, X., & Lu, Q. (2021). The influence of operating room nurses’ job stress on burnout and organizational commitment: The moderating effect of over-commitment. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(4), 1772–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. (2022). Analysis on the literature communication path of new media integrating public mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 997558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.-Y., Hsieh, A.-T., & Chen, C.-Y. (2012). The relationship between workplace friendship and perceived job significance. Journal of Management & Organization, 18(2), 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K. D., & Cullen, J. B. (2006). Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(2), 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. (2017). Finding solutions to the problem of burnout. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(2), 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., Becker, T. E., & Vandenberghe, C. (2004). Employee commitment and motivation: A conceptual analysis and integrative model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Jackson, T. A., McInnis, K. J., Maltin, E. R., & Sheppard, L. (2012). Affective, normative, and continuance commitment levels across cultures: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, T. (2018). L2 teachers’ professional burnout and emotional stress: Facing frustration and demotivation toward one’s profession in a japanese efl context. In J. D. D. Martínez Agudo (Ed.), Emotions in second language teaching (pp. 259–275). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, A., & Steele-Johnson, D. (2012). Individual and relational self-concepts in a team context: Effects on task perceptions, trust, intrinsic motivation, and satisfaction. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 18(5/6), 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nápoles, J. (2022). Burnout: A review of the literature. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 40(2), 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño-Zambrano, M.-A., Cobos-Lozada, C.-A., Mendoza-Becerra, M.-E., Ordóñez-Erazo, H.-A., & García-Sierra, R. (2024). System dynamics model for analysis of demand response on incorporating autoswitch in the Colombian electrical sector. Energy Policy, 193, 114257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parayitam, S., Naina, S. M., Shea, T., Syed Mohideen, A. H., & Aruldoss, A. (2021). The Relationship Between Human Resource Management Practices, Knowledge Management Practices, and Performance: Evidence from the Healthcare Industry in India. Global Business Review, 09721509211037209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. G., Zhu, W., Kwon, B., & Bang, H. (2023). Ethical leadership and follower unethical pro-organizational behavior: Examining the dual influence mechanisms of affective and continuance commitments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(22), 4313–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permarupan, P. Y., Al Mamun, A., Hayat, N., Saufi, R. A., & Samy, N. K. (2021). Nursing management challenges: Effect of quality of work life on depersonalization. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 14(4), 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradesa, H. A., Dawud, J., & Affandi, M. N. (2019). Mediating role of affective commitment in the effect of ethical work climate on felt obligation among public officers. JEMA: Jurnal Ilmiah Bidang Akuntansi Dan Manajemen, 16(2), 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putranta, M. P., & Kingshott, R. P. J. (2011). The relationships between ethical climates, ethical ideologies and organisational commitment within indonesian higher education institutions. Journal of Academic Ethics, 9(1), 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawolle, M., Wallis, M. S. v., Badham, R., & Kehr, H. M. (2016). No fit, no fun: The effect of motive incongruence on job burnout and the mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2019). Research on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is alive, well, and reshaping 21st-century management approaches: Brief reply to locke and schattke. Motivation Science, 5(4), 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2000). Exposure to information technology and its relation to burnout. Behaviour & Information Technology, 19(5), 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023a). Ethical climate and creativity: The moderating role of work autonomy and the mediator role of intrinsic motivation. Cuadernos de Gestión, 23(2), 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023b). Ethical leadership and benevolent climate. The mediating effect of creative self-efficacy and the moderator of continuance commitment. Revista Galega de Economía, 32(3), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023c). The influence of teleworking on creative performance by employees with high academic training: The mediating role of work autonomy, self-efficacy, and creative self-efficacy. Revista Galega de Economía, 32(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2024). Creativity and emotional exhaustion in virtual work environments: The ambiguous role of work autonomy. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(7), 2087–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., Corral-Marfil, J. A., Jiménez-Pérez, Y., & Tarrats-Pons, E. (2025a). Impact of ethical leadership on autonomy and self-efficacy in virtual work environments: The disintegrating effect of an egoistic climate. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., Corral-Marfil, J. A., & Tarrats-Pons, E. (2024a). The relationship between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion in a virtual work environment: A moderated mediation model. Systems, 12(11), 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., González-Carrasco, M., & Miranda-Ayala, R. (2024b). Ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion: The impact of moral intensity and affective commitment. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., González-Carrasco, M., & Miranda-Ayala, R. (2025b). Relationship between ethical climate and burnout: A new approach through work autonomy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., Tarrats-Pons, E., & Corral-Marfil, J.-A. (2023). Effects of intensity of teleworking and creative demands on the cynicism dimension of job burnout. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Dierendonck, D. V., & Gorp, K. V. (1996). Burnout and reciprocity: Towards a dual-level social exchange model. Work & Stress, 10(3), 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. (2013). Stratified cluster sampling. BMJ, 347, f7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setti, I., Lourel, M., & Argentero, P. (2016). The role of affective commitment and perceived social support in protecting emergency workers against burnout and vicarious traumatization. Traumatology, 22(4), 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B., McCaughtry, N., Martin, J., Garn, A., Kulik, N., & Fahlman, M. (2015). The relationship between teacher burnout and student motivation. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, S. S. (2015). An investigation into academic burnout among Taiwanese adolescents from the self-determination theory perspective. Social Psychology of Education, 18(1), 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y., Hur, W.-M., Moon, T. W., & Lee, S. (2019). A motivational perspective on job insecurity: Relationships between job insecurity, intrinsic motivation, and performance and behavioral outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10), 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silistraru, I., Olariu, O., Ciubara, A., Roșca, Ș., Alexa, A.-I., Severin, F., Azoicăi, D., Dănilă, R., Timofeiov, S., & Ciureanu, I.-A. (2024). Stress and burnout among medical specialists in Romania: A comparative study of clinical and surgical physicians. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(2), 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, L., Trudel, L. E., & Babb, J. (2021). I’ve had it! Factors associated with burnout and low organizational commitment in Canadian teachers during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J. P., & Carmeli, A. (2016). The positive effect of expressing negative emotions on knowledge creation capability and performance of project teams. International Journal of Project Management, 34(5), 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.-G., & Vandenberghe, C. (2020). Is affective commitment always good? A look at within-person effects on needs satisfaction and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hoeve, Y., Brouwer, J., & Kunnen, S. (2020). Turnover prevention: The direct and indirect association between organizational job stressors, negative emotions and professional commitment in novice nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(3), 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tierney, P., Farmer, S. M., & Graen, G. B. (1999). An examination of leadership and employee creativity: The relevance of traits and relationships. Personnel Psychology, 52(3), 591–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-T., & Huang, C.-C. (2008). The relationship among ethical climate types, facets of job satisfaction, and the three components of organizational commitment: A study of nurses in Taiwan. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(3), 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Zheng, S., Zhang, F. X., Ma, R., Feng, S., Song, M., Zhu, H., & Jia, H. (2024). The treatment of depersonalization-derealization disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 25(1), 6–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J., & Opoku-Dakwa, A. (2022). Ethical work climate 2.0: A normative reformulation of victor and cullen’s 1988 framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 178(3), 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q., Chiu, T. K. F., Lee, M., Sanusi, I. T., Dai, Y., & Chai, C. S. (2022). A self-determination theory (SDT) design approach for inclusive and diverse artificial intelligence (AI) education. Computers & Education, 189, 104582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Millman, L. S. M., David, A. S., & Hunter, E. C. M. (2023). The prevalence of depersonalization-derealization disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 24(1), 8–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagenczyk, T. J., Purvis, R. L., Cruz, K. S., Thoroughgood, C. N., & Sawyer, K. B. (2021). Context and social exchange: Perceived ethical climate strengthens the relationships between perceived organizational support and organizational identification and commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(22), 4752–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X., Zhang, X., Chen, M., Liu, J., & Wu, C. (2020). The influence of perceived organizational support on police job burnout: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | N | M | SD | BEC | F | GI | SR | DES | IM | AC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benevolent ethical climate (BEC) | 11 | 54.96 | 7.06 | 0.62 | ||||||

| D1: Friendship (F) | 3 | 16.80 | 2.90 | 0.87 ** | 0.64 | |||||

| D2: Group interest (GI) | 4 | 21.20 | 3.10 | 0.92 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.61 | ||||

| D3: Social responsibility (SR) | 4 | 20.40 | 3.50 | 0.86 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.61 | |||

| Depersonalization (DES) | 4 | 20.97 | 3.60 | −0.19 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.22 ** | 0.81 | ||

| Intrinsic motivation (IM) | 5 | 27.08 | 3.05 | 0.36 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.39 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.85 | |

| Affective commitment (AC) | 6 | 29.81 | 4.82 | 0.34 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.35 ** | −0.57 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.83 |

| Predictors | Model 1 (AC) | Model 2 (IM) | Model 3 (AC) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| BEC | 0.19 ** | 0.03 | 5.84 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.03 | 7.74 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.02 | 6.34 ** |

| IM | 0.31 ** | 0.07 | 4.16 ** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.25 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.23 ** | ||||||

| F | 39.74 ** | 59.98 ** | 67.70 *** | ||||||

| Indirect effect IM of BEC on AC: β = 0.05; SE = 0.02 [0.02; 0.08] | |||||||||

| Predictors | Model 1 (IM) | Model 2 (AC) | Model 3 (AC) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| BEC | 0.26 ** | 0.09 | 3.94 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.16 | 3.18 ** | |||

| DES | −0.45 * | 0.24 | −1.87 * | −1.31 * | 0.60 | −2.17 * | |||

| BEC × DES | −0.01 ** | 0.02 | −3.08 ** | −0.02 ** | 0.01 | −2.90 ** | |||

| IM | 0.20 ** | 0.47 | 3.43 ** | ||||||

| IM × DES | −0.01 ** | 0.03 | −2.24 ** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.16 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.15 ** | ||||||

| F | 27.71 ** | 24.20 ** | 24.20 ** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carlos, S.-T.; Yirsa, J.-P.; Elisenda, T.-P. Ethical Climate, Intrinsic Motivation, and Affective Commitment: The Impact of Depersonalization. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15040055

Carlos S-T, Yirsa J-P, Elisenda T-P. Ethical Climate, Intrinsic Motivation, and Affective Commitment: The Impact of Depersonalization. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(4):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15040055

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarlos, Santiago-Torner, Jiménez-Pérez Yirsa, and Tarrats-Pons Elisenda. 2025. "Ethical Climate, Intrinsic Motivation, and Affective Commitment: The Impact of Depersonalization" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 4: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15040055

APA StyleCarlos, S.-T., Yirsa, J.-P., & Elisenda, T.-P. (2025). Ethical Climate, Intrinsic Motivation, and Affective Commitment: The Impact of Depersonalization. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15040055